Abstract

Malagasy genetic diversity results from an exceptional protoglobalization process that took place over a thousand years ago across the Indian Ocean. Previous efforts to locate the Asian origin of Malagasy highlighted Borneo broadly as a potential source, but so far no firm source populations were identified. Here, we have generated genome-wide data from two Southeast Borneo populations, the Banjar and the Ngaju, together with published data from populations across the Indian Ocean region. We find strong support for an origin of the Asian ancestry of Malagasy among the Banjar. This group emerged from the long-standing presence of a Malay Empire trading post in Southeast Borneo, which favored admixture between the Malay and an autochthonous Borneo group, the Ma’anyan. Reconciling genetic, historical, and linguistic data, we show that the Banjar, in Malay-led voyages, were the most probable Asian source among the analyzed groups in the founding of the Malagasy gene pool.

Keywords: Madagascar, Austronesian, Borneo, Banjar, genome-wide.

The Malagasy are the descendants of a unique prehistoric admixture event between African and Asian individuals, the outcome of one of the earliest protoglobalization processes that began approximately 4,000 years before present (BP) (Fuller et al. 2011; Beaujard 2012a, 2012b; Lawler 2014). Today, this island population in the western Indian Ocean shows strong biological (Fourquet et al. 1974; Pierron et al. 2014) and linguistic (Adelaar 2009b; Serva et al. 2012) connections to east coast African and Island Southeast Asian groups. Although this remarkable admixture event has long been studied (Fourquet et al. 1974; Hewitt et al. 1996; Soodyall et al. 1996; Hurles et al. 2005; Tofanelli et al. 2009; Pierron et al. 2014; Kusuma et al. 2015), the settlement process—specifically the geographic origin of the populations involved, dates of settlement and the nature of the population admixture event—are still routinely debated (Adelaar 2009b; Beaujard 2012a; Pierron et al. 2014; Kusuma et al. 2015; Adelaar forthcoming). Both linguistic and genetic studies suggest that the western and central regions of Indonesia (particularly Java, Borneo, and Sulawesi) have the closest Asian genetic connections with modern Malagasy (Kusuma et al. 2015 , 2016; Adelaar forthcoming), and the island was probably settled by a small founding population (Cox et al. 2012). More specifically, recent anthropological research points to the Southeast region of Borneo as a potential source location for Malagasy (Kusuma et al. 2016; Adelaar forthcoming). However, the Indonesian parental population of the Malagasy has so far not been clearly identified (Kusuma et al. 2015 , 2016). To better reconstruct the settlement history of Madagascar and identify the Asian source populations, we conducted widespread sampling and genome-wide analysis of human groups across the Indian Ocean region. In particular, we present here new genome-wide data for two southeast Borneo populations, the Banjar (n = 16) and the Ngaju (n = 25) (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online), which have previously been noted as potential parental groups to the Malagasy (Adelaar forthcoming). The newly generated data were analyzed in the context of previously published data for a wide range of populations from the Indian Ocean rim (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online).

The Malagasy Asian Ancestry Derives from Southeast Borneo

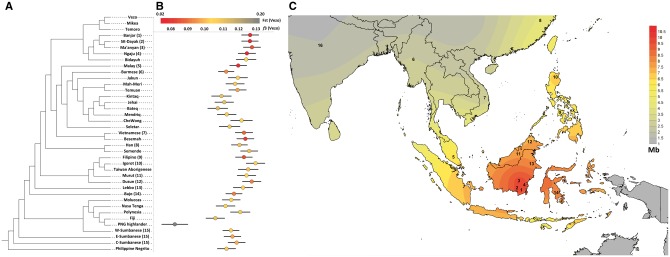

To identify the most probable Asian parental groups of the Malagasy, we adopted a two-stage approach: first, we identified the most likely proxy populations using a data set with wide geographical coverage but relatively low density of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), then followed by a higher density SNP data set that gives increased statistical power. This allows us to reconstruct the admixture processes that led to the emergence of modern Malagasy. The admixture profile of our data set (2,183 individuals from 61 populations genotyped for 40,272 SNPs; supplementary figs. S2 and S3, Supplementary Material online), based on ADMIXTURE analyses (Alexander et al. 2009), shows that the Malagasy genetic diversity is best described as a mixture of 68% African genomic components and 32% Asian components, corresponding well with the results of previous studies (Capredon et al. 2013; Pierron et al. 2014). While the African ancestry component in Malagasy appears to be broadly similar to that still present today in South African Bantu, the Asian ancestry presents a more complex pattern. This complexity is the key reason why previous studies have been unable to point firmly to a unique Asian source, making any subsequent anthropological inferences debatable (Pierron et al. 2014). This problem arose with a study of the Ma’anyan population of Borneo, whose language has long been identified as the closest to the Malagasy language (Dahl 1951), but who surprisingly exhibit no clear genetic connection to Malagasy (Kusuma et al. 2016). Instead, the higher genetic complexity of the Asian ancestry component in Malagasy likely reflects the fact that more than a single source population was involved in its formation. Affinities to the Malagasy Asian components are found at high frequency across several Island Southeast Asian groups, but notably in Malay, a dominant group of ancient seafaring traders (first millennium CE), and admixed groups from Borneo (i.e., Banjar, Ngaju, South Kalimantan Dayak, Lebbo, Murut, Dusun, and Bidayuh; supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online). The connection between Malagasy, and the Borneo and Malay populations, is supported by f3-statistics (z-scores<−2; supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online) (Patterson et al. 2012) and TreeMix analyses (35% of Malay/Borneo gene flow to Malagasy; supplementary fig. S4, Supplementary Material online) (Pickrell and Pritchard 2012). However, to more specifically identify the Asian ancestry of the Malagasy genome, we performed a Local Ancestry analysis with PCAdmix (Brisbin et al. 2012) using two proxy parental meta-populations comprising 100 individuals with African ancestry (randomly selected from Yoruba, South African Bantu, Kenyan Luhya, and Somali groups) and Asian ancestry (randomly selected from Chinese, Philippine Igorot, Bornean Ma’anyan, and Malay groups). Masking the haplotypes inferred to derive from Africa, we performed an ancestry-specific Principal Components Analysis (PCA) (Patterson et al. 2006) and TreeMix analysis (Pickrell and Pritchard 2012). Both show that the Asian genomic components of Malagasy cluster tightly with Southeast Borneo groups (Banjar, South Kalimantan Dayak, Ngaju, and Ma’anyan) (1,664 SNPs; fig. 1A and supplementary fig. S5, Supplementary Material online). This connection is supported by the highest f 3-statistics and the lowest FST genetic distances also being observed between Asian ancestry of the Malagasy and these same Southeast Borneo groups (f3 > 0.12; FST < 0.02; fig. 1B; supplementary tables S3 and S4, Supplementary Material online).

Fig. 1.

Localization of the Asian ancestry of Malagasy by (A) a TreeMix dendrogram, (B) FST distances and f3 statistics, all based on the Asian-SNP data set, and (C) a shared identity-by-descent (IBD) analysis based on haplotypes inferred from the high density of SNP data set. (A) The TreeMix dendrogram was inferred imposing no a priori assumptions of migration, displaying only the tree topology. (B) Values of the f3 (Asian-SNP Vezo, X; Yoruba) statistics are represented by dots with standard error bars. The color of each dot corresponds to the FST distances between the Asian ancestry of the Vezo and each Asian population using a gray-yellow-red color scale from the highest (0.196) to the lowest values (0.02). (C) The cumulative shared IBD (Mb) between pairs of Malagasy:Asian individuals were averaged to obtain one value of IBD sharing per Asian population. The obtained values are represented by a gray-yellow-red color scale. The numbers 1–15 correspond to the populations presented on the TreeMix dendrogram with the addition of 16 which stands for Brahmin Indian.

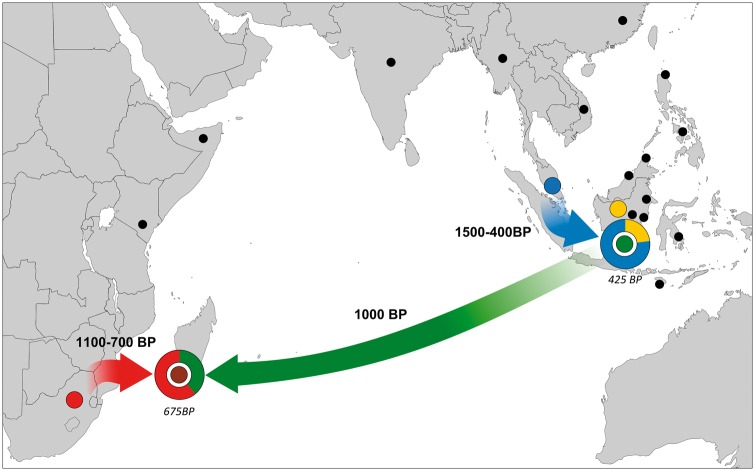

To explore this connection in more detail, we turned to the high density SNP data set (551 individuals from 24 populations genotyped for 374,189 SNPs; supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). This allows more statistically powerful analyses based on haplotypes. We confirmed the earlier result that Malagasy have the highest values of cumulative shared identity-by-descent fragments with Southeast Borneo populations (fig. 1C; supplementary fig. S6, Supplementary Material online). To expand on this, however, we inferred the population sources of the Malagasy, their relative ratios and the dates of potential admixture events with GLOBETROTTER (Hellenthal et al. 2014), defining each population in our data set as a donor/surrogate group and the Malagasy as the recipient, using the haplotype “painting” data obtained with Chromopainter (Lawson et al. 2012). The best fit outcome for the Malagasy was obtained under a model of a single admixture event between two sources: the Banjar representing 37% of modern Malagasy and the South African Bantu population representing the other 63% (r2 = 0.99, P < 0.01; fig. 2 and supplementary table S5, Supplementary Material online). The admixture event was dated to 675 years BP (95% CI: 625–725 years BP, supplementary table S5, Supplementary Material online), which is similar to the dates of admixture estimated by ALDER (550–750 years BP) using Banjar population in combination with the South African Bantu (supplementary table S6, Supplementary Material online) (Loh et al. 2013). When each Malagasy ethnic group is analyzed separately, similar parental populations, admixture proportions, and dates are obtained with the noticeable older estimated dates toward the east coast of Madagascar (supplementary table S5, Supplementary Material online).

Fig. 2.

Scenario for the Asian genetic ancestry in Malagasy based on the best fit models inferred by GLOBETROTTER. The brown circle represents the Malagasy (bottom left), while the green circle represents the Banjar (right). Red semicircles show the African ancestry (South African Bantu), whereas the other semicircles represent Asian ancestry from Malay (blue), Banjar (green), and Ma’anyan (yellow). Black dots highlight other populations included in the high density genomic data set. The arrows show migration events, with indicative routes, inferred in our analyses with dates of admixture in italic estimated by GLOBETROTTER. Dates in bold correspond to dates of migration estimated from archaeological and historical data (Beaujard 2012a).

Crucially, these dates of genetic admixture, in agreement with a previous study (Pierron et al. 2014), reflect the midpoint or end of noticeable admixture between groups of Asian and African ancestry in Madagascar, rather than the start of this contact. Therefore, they could correspond to the end of the period of the main Austronesian presence in Madagascar that started around the first millennium CE (Dahl 1951, 1991; Dewar and Wright 1993; Adelaar 1995; Cox et al. 2012; Adelaar forthcoming). On the other hand, around 1100–700 years BP, climatic changes in the South of Africa forced Bantu populations to move to more hospitable places (Huffman 2000). This South Bantu migration has previously been suggested as an explanation for the higher density of populations observed in the South of Madagascar (Beaujard 2012a). As all of our sampled groups live in the South of Madagascar, and considering that the estimated dates of admixture are more recent on the west coast (supplementary tables S5 and S6, Supplementary Material online), it is tempting to interpret our admixture date as marking the last significant Bantu migration to Madagascar, perhaps initiated by climatic changes in Africa.

The Proto-Malagasy People Were a Malay-Ma’anyan Admixed Group

These analyses clearly identify an Austronesian-speaking population, the Banjar in the southeast region of Borneo, as the closest Asian sources for modern Malagasy. Linguistic reconstruction of the Proto-Malagasy language indicated that it appears to be derived mainly from the Southeast Barito language spoken today by the Ma’anyan (Dahl 1951), a Southeast Borneo group. However, we have previously shown (Kusuma et al. 2016), and reconfirm here, that in genetic analyses, the Ma’anyan are only distantly related to the Malagasy in terms of genetics. In contrast, the Banjar currently speak a Malay language. Interestingly, the linguistic studies indicated a noticeable proportion of Malay words in present-day Malagasy languages (Adelaar 1989, 2009b). We estimated the best fit scenario for the admixture process by modeling the current Banjar diversity with GLOBETROTTER (Hellenthal et al. 2014). The genetic diversity of the Banjar best fits a model of a unique admixture event (r2 = 0.62; P < 0.01) between two major ancestries that can be traced back to Malay (77%) and Ma’anyan (23%) (fig. 2 and supplementary table S5, Supplementary Material online). We estimate the date of the last noticeable admixture approximately 425 years BP (95% CI: 275–500 years BP). Since the Banjar originated from a Ma’anyan-Malay admixture, at a time preceding the supposed date of migration to Madagascar (i.e., 1000 years BP), the ancestors of the Banjar were presumably speaking a language close to that reconstructed for Proto-Malagasy (Adelaar forthcoming). Although we cannot fully exclude that the Malay-Ma’anyan admixture occurred in Malagasy, prior to the Bantu gene flow, the observed haplotypic structure is so similar to the ones observed in the Banjar that it is more parsimonious to interpret this admixture to have happened first in Borneo. This analysis reconciles both the linguistic and genetic data, strengthening our scenario placing the Banjar as the main Asian parental populations of the Malagasy. Their current genetic diversity appears to be the reflection of the historical relationship between Madagascar, Southeast Borneo, and the Malay. The maritime routes linking Madagascar to Borneo were particularly exploited during the rapid expansion of trading networks led by the Hindu Malay Kingdoms, such as Srivijaya (6th–13th centuries) (Ras 1968; Beaujard 2012a). Established on the islands of Sumatra and Java, the Malay traded with far-distant regions, notably across East Asia and reaching as far as East Africa (Beaujard 2012a). Their influence increased across all the Southeast Asian islands, notably in Borneo where they established several trading posts, such as one in the city of Banjarmasin in Southeast Borneo (Ras 1968; Beaujard 2012a). As related in the only Banjarese historical records available, the Hikayat Banjar (“Tale of Banjar”) (Ras 1968), the main city of the Banjar population was a major trading post in the former Malay Empires. This probably favored interactions with inland groups in Borneo, such as the Ma’anyan, but also with other populations such as the Bajo sea nomads (supplementary fig. S6 and table S5, Supplementary Material online) (Adelaar 2009a; Beaujard 2012a; Kusuma et al. 2015). The Malay domination of trading networks collapsed during the 15th–16th centuries, with the emergence of several sultanates and the arrival of Europeans, which could correspond to the end of noticeable Malay gene flow into the Banjar population, as indicated by our estimated date of admixture between Malay and Ma’anyan around 425 years BP.

Our study provides strong support for a new scenario for the Austronesian settlement of Madagascar, reconciling cultural, linguistic, and genetic data, in which the Banjar population played key roles in establishing the Asian founder population of the Malagasy. The Malay trading networks during the first millennium CE triggered one of the earliest protoglobalization processes, bringing Southeast Asian populations to East Africa (Beaujard 2012a). The Banjar, currently living in Southeast Borneo, show the highest affinity to the main genetic ancestry component in Malagasy and can therefore be suggested to be likely to have been the ethnic group that accompanied the Malay in their maritime voyages to Madagascar. This population with composite ethnic ancestry emerged from the long-standing presence of Malay in Borneo, creating an admixed community with local Austronesian-speaking groups, such as the Ma’anyan. Before the probable date of migration (around 1000 years BP), the ancestors of the current Banjar would have contained both Malay and Ma’anyan genetic diversity, and probably linguistic inheritances from both (Adelaar forthcoming). Although the exact maritime route(s) of migration from Borneo to Madagascar are still an open question, our study identifies the flow of Malay-Ma’anyan genomic ancestries as carried by Banjar ancestors as the source to Malagasy.

Materials and Methods

All experimental and analytical procedures are described in the supplementary method file, Supplementary Material online. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Commission of the Eijkman Institute for Molecular Biology (Jakarta, Indonesia).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at Molecular Biology and Evolution online (http://www.mbe.oxfordjournals.org/).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Eijkman Institute for Molecular Biology (Jakarta, Indonesia), especially Alida Harahap and Deni Feriandika, and the Department of Health, Banjarmasin city in the province of South Kalimantan, for accommodating the sampling program. The authors wish to acknowledge support from the GenoToul bioinformatics facility of the Genopole Toulouse Midi Pyrénées, France. They also thank Harilanto Razafindrazaka for her useful comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by French ANR grant number ANR-14-CE31-0013-01 (grant OceoAdapto to F.-X.R.), the French Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs (French Archaeological Mission in Borneo (MAFBO) to F.-X.R.), and the French Embassy in Indonesia through its Cultural and Cooperation Services (Institut Français en Indonésie). Genetic data have been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA, https://ega-archive.org), jointly managed by the EBI and CRG, under accession number EGAS00001001841.

References

- Adelaar KA. 2009a. Towards an Integrated Theory about the lndonesian Migrations to Madagascar In: Peregrine PN, Peiros I, M. F, editors. Ancient human migrations: a multidisciplinary approach. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. p. 149–172. [Google Scholar]

- Adelaar KA. 1989. Malay influence on Malagasy: linguistic and culture-historical implications. Ocean Linguist. 28:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Adelaar KA. 1995. Borneo as a cross-roads for comparative Austronesian linguistics In: Fox JJ, Tryon D, Bellwood P, editor. The Austronesians: comparative and historical perspectives. Canberra (Australia): The Australian National University. p. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Adelaar KA. 2009b. Loanwords in Malagasy In: Haspelmath M, Tadmor U, editors. Loanwords in the world’s languages: a comparative handbook. Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter Mouton; p. 717–746. [Google Scholar]

- Adelaar KA. Forthcoming. Who were the first Malagasy, and what did they speak? In: Acri A, Landmann A, editors. Cultural Transfer in Early Monsoon Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. 2009. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 19:1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaujard P. 2012a. Les mondes de l’ocean indien. Vol. 2: L’océan Indien, au cœur des globalisations de l'Ancien Monde (7e-15e siècles). Paris, France: Armand Collin.

- Beaujard P. 2012b. Les mondes de l’océan Indien. Vol. 1: De la formation de l’État au premier système-monde afro-eurasien (4e millénaire av. J.-C.-6e siècle apr. J.-C.). Paris, France: Armand Collin.

- Brisbin A, Bryc K, Byrnes J, Zakharia F, Omberg L, Degenhardt J, Reynolds A, Ostrer H, Mezey JG, Bustamante CD. 2012. PCAdmix: principal components-based assignment of ancestry along each chromosome in individuals with admixed ancestry from two or more populations. Hum Biol. 84:343–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capredon M, Brucato N, Tonasso L, Choesmel-Cadamuro V, Ricaut F-X, Razafindrazaka H, Rakotondrabe AB, Ratolojanahary MA, Randriamarolaza L-P, Champion Bet al. 2013. Tracing Arab-Islamic inheritance in Madagascar: study of the Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA in the Antemoro. PLoS One 8:e80932.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MP, Nelson MG, Tumonggor MK, Ricaut F-X, Sudoyo H. 2012. A small cohort of Island Southeast Asian women founded Madagascar. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 279:2761–2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl OC. 1951. Malgache et maanjan: une comparaison linguistique. Oslo, Norway: Edege-Intituttet. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl OC. 1991. Migration from Kalimantan to Madagascar. Oslo, Norway: Norwegian University Press: Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture. [Google Scholar]

- Dewar RE, Wright HT. 1993. The culture history of Madagascar. J World Prehist. 7:417–466. [Google Scholar]

- Fourquet R, Sarthou J, Roux J, Aori K. 1974. Hemoglobine S et origines du peuplement de Madagascar: nouvelle hypothese sur son introduction en Afrique [Hemoglobin S and origins for the settlement of Madagascar: new hypothesis on its introduction to Africa]. Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar. 43:185–220. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DQ, Boivin N, Hoogervorst T, Allaby R. 2011. Across the Indian Ocean: the prehistoric movement of plants and animals. Antiquity 85:544–558. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenthal G, Busby GB, Band G, Wilson JF, Capelli C, Falush D, Myers S. 2014. A genetic atlas of human admixture history. Science 343:747–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt R, Krause A, Goldman A, Campbell G, Jenkins T. 1996. Beta-globin haplotype analysis suggests that a major source of Malagasy ancestry is derived from Bantu-speaking Negroids. Am J Hum Genet. 58:1303–1308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman TN. 2000. Mapungubwe and the origins of the Zimbabwe culture In: Leslie M, Maggs T, editors. African naissance: The Limpopo valley 1000 years ago. Cape Town, South Africa: South African Archaeological Society; p. 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hurles ME, Sykes BC, Jobling MA, Forster P. 2005. The dual origin of the Malagasy in Island Southeast Asia and East Africa: evidence from maternal and paternal lineages. Am J Hum Genet. 76:894–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma P, Brucato N, Cox MP, Pierron D, Razafindrazaka H, Adelaar A, Sudoyo H, Letellier T, Ricaut F-X. 2016. Contrasting linguistic and genetic influences during the Austronesian Settlement of Madagascar. Sci Rep. 6:26066.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma P, Cox MP, Pierron D, Razafindrazaka H, Brucato N, Tonasso L, Suryadi HL, Letellier T, Sudoyo H, Ricaut F-X. 2015. Mitochondrial DNA and the Y chromosome suggest the settlement of Madagascar by Indonesian sea nomad populations. BMC Genomics 16:191.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler A. 2014. Sailing Sinbad's seas. Science 344:1440–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson DJ, Hellenthal G, Myers S, Falush D. 2012. Inference of population structure using dense haplotype data. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002453.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh PR, Lipson M, Patterson N, Moorjani P, Pickrell JK, Reich D, Berger B. 2013. Inferring admixture histories of human populations using linkage disequilibrium. Genetics 193:1233–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D. 2006. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2:e190.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson NJ, Moorjani P, Luo Y, Mallick S, Rohland N, Zhan Y, Genschoreck T, Webster T, Reich D. 2012. Ancient admixture in human history. Genetics 192:1065–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell JK, Pritchard JK. 2012. Inference of population splits and mixtures from genome-wide allele frequency data. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002967.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierron D, Razafindrazaka H, Pagani L, Ricaut F-X, Antao T, Capredon M, Sambo C, Radimilahy C, Rakotoarisoa J-A, Blench RM, et al. 2014. Genome-wide evidence of Austronesian–Bantu admixture and cultural reversion in a hunter-gatherer group of Madagascar. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.111:936–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ras JJ. 1968. Hikajat Banjar: a study in Malay historiography. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Serva M, Petroni F, Volchenkov D, Wichmann S. 2012. Malagasy dialects and the peopling of Madagascar. J R Soc Interface. 9:54–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soodyall H, Jenkins T, Hewitt R, Krause A, Stoneking M. 1996. The peopling of Madagascar In: Boyce A, Mascie-Taylor C, editors. Molecular biology and human diversity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; p. 156–170. [Google Scholar]

- Tofanelli S, Bertoncini S, Castri L, Luiselli D, Calafell F, Donati G, Paoli G. 2009. On the origins and admixture of Malagasy: new evidence from high-resolution analyses of paternal and maternal lineages. Mol Biol Evol. 26:2109–2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.