Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to assess the current status and future trends in telepathology (TP) and digital pathology (DP) in central India.

Materials and Methods:

A self-constructed questionnaire including 12 questions was designed with five specialists, to improve the design ambiguity. The study was conducted through postal and online survey consisting of 12 questions and sent to 300 histopathologists.

Results:

A total of 247 histopathologists answered the survey. The overall response rate was 81%. 98% pathologists felt the need for TP and DP. 34% pathologists used digital photomicrographic images in routine practice. Utilization of DP in most efficient way was observed by 48% pathologists mainly for the purpose of teaching in academic institutions. 82% believed that TP is helpful to take an expert opinion whereas only26% believed that a second opinion has to be taken. With respect to limitations, 67% pathologists believed that its cost-effective whereas 51% revealed high use of TP in next 5 years.

Conclusions:

Our survey shows that as the field evolves, pathologists are more towards welcoming TP and DP, provided frequent workshops and training programs are conducted. The results of this survey indicates that pathology staff across central India currently utilize gross digital images for educational or academic purposes. They also revealed that technology will be required in near future applications in academics, consultation and for medico-legal purposes.

Key Words: Academics, consultation, digital pathology, telepathology, medico-legal purposes

INTRODUCTION

Pathology, as with most medical specialties, is currently facing a growing demand to improve quality, patient safety and diagnostic accuracy because there is an increasing emphasis on sub-specialization. These factors, coupled with economic pressures to consolidate and centralize diagnostic services, are driving the development of systems that can optimize access to expert opinion and highly specialized pathology services. Among the many functions of an anatomic pathologist are diagnosis, consultation, documentation and education. Implicit in these activities is the necessity to document morphological findings both at the macroscopic and microscopic levels.[1,2] Traditionally, this has been achieved through the process of descriptive prose with inherent idiosyncratic variations in the style, vocabulary and abilities of individual pathologists and other staff performing gross dissection and there by its histopathologic slide.[3] Often the difference between making a specific diagnosis and a generic pathological process is determined by the gross description including what the gross lesion looked like, its photomicrographic structure, where the lesion occurred and how the lesions were distributed.[4] Digital photographs document the true appearances of the pathological changes and may eliminate inaccuracies resulting from variations in descriptive ability.

Since pathology is a visual science, the inclusion of quality digital images into lectures, teaching handouts and electronic documents is crucial.[5] When incorporated with synoptic texts, reports are more accurate and concise.[6] In addition, block keys and hand-drawn diagrams can be substituted with digital photographs.[3] In this way, digital photography has changed the face of the pathology report significantly,[7] allowing the incorporation of colored prints of the gross specimen as well as of relevant microscopic features. Some have even gone so far as to suggest that high-resolution digital images could eventually replace word descriptions of macroscopic specimens as well as histopathologic images.[8]

In addition to improving current practice, the transition to the digital medium has opened up numerous applications for gross as well as histopathologies such as telepathology (TP), three-dimension (3D) image technology and perhaps future automated machine vision systems. TP is already practiced to varying degrees world wide and is primarily used for diagnostic and consultation purposes.[9,10,11] At a microscopic level, 3D digital simulations provide and may become a possible future necessity for digital diagnostic pathology practice.[12] In addition, there are several digital imaging applications which are emerging in pathology, such as image analysis using algorithms, coupled with computer-assisted diagnosis and 3D-imaging, which have enhanced the field of biomedical informatics.[13]

However, in India, the exact usage and applications of the technology are not very well known. Therefore, standardized applications of these methods are not identified or are thought to be under utilized in pathology laboratories across the country. A standardized method of obtaining, storing and sharing digital images is needed and can lead to better diagnostic techniques and consultation methods for pathology diagnosis,[1,7,14,15,16] however, these procedures have yet to materialize.[1,7,17,18,19] In addition, utilizing digital images for teaching and consultation can be more effective for storage purposes and have easier accessibility as compared to traditional print photographs and slides. There is very little data assessing the utilization of microscopic digital images in India.

This survey will attempt to give a better overall picture of attitude of pathologists and pathology residents in India toward the spectrum of digital pathology (DP) applications and examine the perceived future direction of this technology. It may also identify opportunities for further education, research and software development in this field.

METHODS

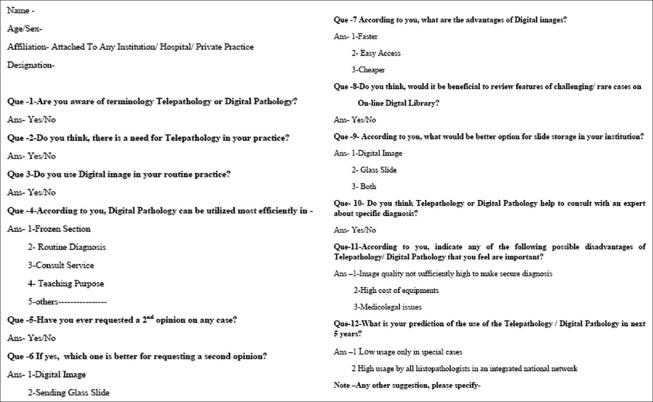

After approval by the Institutional Ethical Committee, a self-constructed questionnaire [Figure 1] including 12 questions was designed with five specialists to improve the design without any ambiguity. The survey was delivered through post and online to 300 histopathologists. Emails were sent to all available contacts. The survey was designed and focused on the type of respondent, knowledge of microscopic digital photography, current usage, strengths and weaknesses and perceived future direction of digital photography in the pathology laboratory. The requested answers were in the form of yes/no, multiple choice and free text questions. The results were evaluated using comparison amongst all the groups.

Figure 1.

Questionnaire for survey

RESULTS

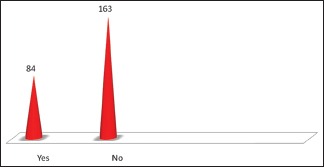

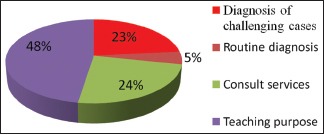

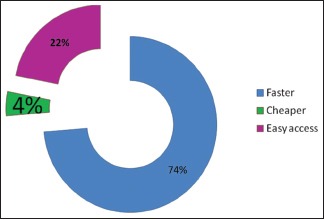

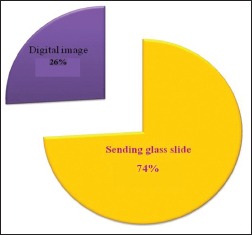

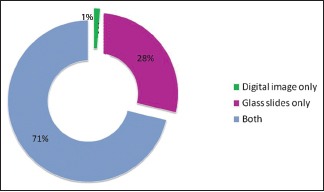

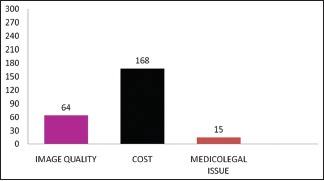

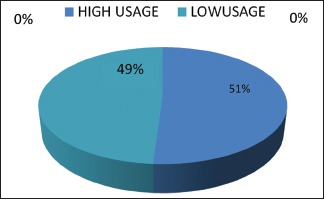

Of 300, a total of 247 histopathologists answered the survey. The overall response rate was 81%. A total of 163 pathologists used digital images on a routine basis whereas 84 do it in conventional way (Graph 1). When utilization of DP in most efficient way was evaluated in survey, maximum of 48% pathologist agreed to its use for academic purposes whereas only 24% utilized it for consultation point of view (Graph 2). When asked about whether DP or TP is helpful to take an expert opinion, 82% pathologists agreed over the view (Graph 3). About 74% of individuals in survey agreed about the advantage of digital microscopic images in pathology (Graph 4) as its a faster mode of information in this day to day life, but when evaluated for DP as better option for requesting the second opinion only 26% of pathologist agreed over it (Graph 5). With respect to better option for storage of data 71% pathologists agreed that they store it in both the format, i.e., in form of glass slides as well as in digital images (Graph 6). While answering about limitation of DP, 68% answered that because of its cost-effectiveness (Graph 7). When asked regarding opinion of pathologists about prediction for use of TP/DP in next 5 years, 51% of individuals agreed of its high usage and recommendation in coming 5 years (Graph 8).

Graph 1.

The overall response rate of the survey

Graph 2.

Utilization of digital pathology in most efficient purpose

Graph 3.

Digital pathology or telepathology helpful to take an expert opinion

Graph 4.

Advantage of digital microscopic images in pathology

Graph 5.

Better option for requesting second opinion

Graph 6.

Better option for storage of data

Graph 7.

Limitation of digital pathology

Graph 8.

Prediction for use of telepathology/digital pathology in next 5 years

DISCUSSION

Overall, pathology informatics and specifically digital photomicrography has become a common place in pathology laboratories across India. Majority of its users being pathologist, residents and pathologist's assistants, photograph (document) histologic specimens with a digital camera. The images are then stored digitally into a centralized data base that is easily accessible for the laboratory personnel. In most academic institutions, almost all surgical cases are digitally photographed which are usually documented as interesting, medico-legal or complicated cases. After being archived, the digital images are usually accessed by pathologists, residents and medical staff for teaching in clinical rounds, resident education and conferences. In addition, they are accessed for medico-legal and consultation purposes. There is a wide range of perceived disadvantages to digital photography like storage issues are a major concern among the respondents. Archiving of photomicrograph is extremely important for multiple reasons. First, the complexity of archiving will increase with multiple users and acquisition devices plus the ease of retrieval and utilization of these images needs to be managed successfully. Second, image files may be quite large. If necessary, this can be circumvented by file compression, the compaction of an image by removal of redundant information, helps with image processing, storage and transmission. Ideally, acquired pictures should be embedded into pathology reports and then captured directly into a laboratory information system.[12]

Another area of concern appears to be the cost associated with digital photomicrography. In fact, the most important issues in pathology informatics are challenges associated with the cost of electronic storage. The majority of the costs are associated with building of the new system and training of the pathology health staff which require significant spending.[9] However, after the initial capital investment, the additional operating costs are minimal and can be balanced by the elimination of expenses associated with storage and retrieval of physical images.[9] Reduced costs and extensive applications make the adoption of digital imaging in anatomical pathology laboratories an essential consideration.[3,19]

A major concern identified in our survey was agreement on need for digital photomicrography. Indeed, in our survey, almost 100% of the respondents felt the use of digital photography, indicating reliance on older technique of images or no photography used at all at their institution. This may be attributed to a lack of understanding of the applications of digital photomicrography and the associated limitations and reduced control over this technology.[9] However, a failure to adopt a digital imaging technology may be considered a deficiency of practice.[20] Indeed, if the reporting pathologist does not employ such a system for proper documentation, back-up or quality assurance it may be considered as negligence medico-legally.[2] When asked regarding DP for expert as well as second opinion almost 70–80% respondents were in agreement, suggesting that it is easy to communicate and transfer those stored images through internet software programming and taking an opinion from senior consultant pathologists in the diagnostic procedure.

There are some limitations identified in this survey that warrant discussion. In particular, the sample size of the survey was of concern. Our reliance on the known contacts of the authors and their contacts was the best known option. Despite this limitation, the response rate of the survey was 60–70% and is well above of what is expected for this type of study. Furthermore, as the survey was distributed to current employees known to be directly involved in digital photomicrography. This could be considered a bias, as the respondents are more familiar with this topic and may not be representative of the pathology community at large. In addition, as with other voluntary studies, not all individuals are inclined to participate. In general, only those with strong opinions are more likely to respond. In this case, probably those respondents who have either strongly positive or negative experiences with digital photomicrography were most likely to respond to the survey. When surveyed regarding scope of telepathology in future 5 years, 51% were in agreement for the use of it which might be due to its advantage of quick transfer for second opinion, expert opinion and storage of large amount of data in a small area like computers as well as hard disk drives.

CONCLUSION

From its genesis as an interesting idea in the late 1990s, DP and TP has become a useful and valuable tool in clinical and research pathology. This transition was initially fueled by the development of digital slide scanners, fluorescent slide scanners, multi spectral imaging hardware and computational horse power. Today, integrated systems with increasingly complex and functional software tools are being developed and will become part of our diagnostic tool box as we move into personalized medicine. Of the various barriers to widespread adoption that were described above, comprehensive validation of this technology for diagnostic purposes across the complete spectrum of surgical pathology, represents the most important. As this process unfolds, DP will undoubtedly open up new avenues for computational exploration of individual disease tissues and will transform the practice of pathology.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghaznavi F, Evans A, Madabhushi A, Feldman M. Digital imaging in pathology: Whole-slide imaging and beyond. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;8:331–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-120902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leong A, James C, Thomas A. Handbook of Surgical Pathology. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leong FJ, Leong AS. Digital imaging in pathology: Theoretical and practical considerations, and applications. Pathology. 2004;36:234–41. doi: 10.1080/00313020410001692576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stromberg PC. Fundamental Principles of Descriptive Anatomic Pathology (How to Describe and Interpret What you See) Charles Louis Davis Foundation for the Advancement of Veterinary and Comparative Pathology. 2007. [Last retrieved on 2013 May 7]. Available from: http://www.cldavis.org/cgi-bin/download.cgi.pid=915 .

- 5.Riley RS, Ben-Ezra JM, Massey D, Slyter RL, Romagnoli G. Digital photography: A primer for pathologists. J Clin Lab Anal. 2004;18:91–128. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leong AS. Synoptic/checklist reporting of breast biopsies: Has the time come? Breast J. 2001;7:271–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2001.21001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellis M, Metias S, Naugler C, Pollett A, Jothy S, Yousef GM. Digital pathology: Attitudes and practices in the Canadian pathology community. J Pathol Inform. 2013;4:3. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.108540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leong AS, Visinoni F, Visinoni C, Milios J. An advanced digital image-capture computer system for gross specimens: A substitute for gross description. Pathology. 2000;32:131–5. doi: 10.1080/003130200104385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabril MY, Yousef GM. Informatics for practicing anatomical pathologists: Marking a new era in pathology practice. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:349–58. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cross SS, Dennis T, Start RD. Telepathology: Current status and future prospects in diagnostic histopathology. Histopathology. 2002;41:91–109. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leong FM, Graham A, Gahm T, McGee J. Telepathology: Clinical utility and methodology. In: Underwood J, editor. Recent Advances in Histopathology. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. pp. 217–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parwani AV, Feldman M, Balis U, Pantanowitz L. Digital imaging. In: Pantanowitz L, Tuthill JM, Balis UG, editors. Pathology Informatics: Theory and Practice. Chicago: American Society for Clinical Pathology; 2012. pp. 231–56. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paxton A. Digging Its Way In: Lab Digital Imaging. College of American Pathologists. 2005. [Last retrieved on 2013 May 10]. Available from: http://www.cap.org/apps/cap.portal?_nfpb=true and cntvwrPtlt_actionOverride=/portlets/contentViewer/show and _WindowLabel=cntvwrPtlt and _state=maximized and _pageLabel=cntvwrand cntvwrPtlt%7BactionForm.ContentReference%7D=cap_today/featurestories/0505digital.html .

- 14.Yagi Y, Gilbertson JR. Digital imaging in pathology: The case for standardization. J Telemed Telecare. 2005;11:109–16. doi: 10.1258/1357633053688705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh R, Chubb L, Pantanowitz L, Parwani A. Standardization in digital pathology: Supplement 145 of the DICOM standards. J Pathol Inform. 2011;2:23. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.80719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pantanowitz L. Digital images and the future of digital pathology. J Pathol Inform. 2010;1:15. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.68332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Janabi S, Huisman A, Van Diest PJ. Digital pathology: Current status and future perspectives. Histopathology. 2012;61:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedvat CV. Digital microscopy: Past, present, and future. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1666–70. doi: 10.5858/2009-0579-RAR1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruz D, Seixas M. A surgical pathology system for gross specimen examination. Proc AMIA Symp. 1999:236–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leong FJ, Leong AS. Digital photography in anatomical pathology. J Postgrad Med. 2004;50:62–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]