INTRODUCTION

Oral cancer constitutes about 20 persons per 1 lakh population in India which accounts for about 30% of all types of cancers. Over five people die every hour every day due to oral cancer. International Agency for Research on Cancer has predicted that the Indian incidence of oral cancer will be 1.7 billion by 2035. Around 90-95% of oral cancers in India are squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs).[1]

Conventional SCC is relatively easy to diagnose on histopathology. Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) can be keratinizing or non-keratinizing. Non-keratinizing SCC shows absence of keratinisation and keratin pearl formation whereas this is the most common feature of keratinizing SCC.[2]

OSCC histologically is composed of dysplastic epithelial cells showing variable degrees of squamous differentiation. Well-differentiated cells almost perfectly recapitulate normal squamous cells. These dysplastic cells demonstrate basement membrane violation and invade the underlying connective tissue in the form of nests, islands, sheets etc. The tumour cells show disorganized growth, loss of polarity, dyskeratosis, keratin pearls, intercellular bridges, an increase in nuclear cytoplasmic ratio, nuclear chromatin irregularities and increased mitotic figures as the most common findings.[3,4]

The pattern of invasion at the advancing front of the tumour is significant and is an independent predictor of both local recurrence and overall survival. The most unfavourable pattern is described as diffuse infiltration with cellular dissociation, while the most favourable pattern is well defined with “pushing” border.[2] An inflammatory infiltrate consisting predominantly of lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages is seen at the tumour-stroma interface. Variable desmoplastic fibrous stroma, tumour associated fibroblasts and endothelial cells can also be seen.[4,5]

Although OSCC is the most common malignancy of oral cavity which can be diagnosed effortlessly based on the above described features, some cases show rare histopathological deviations which are not commonly found in conventional OSCC. These include clear cell change, epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT), stromal desmoplasia, hyalinization, neural invasion, vascular invasion, tissue eosinophilia, giant cell and tertiary lymphoid follicle formation.

CLEAR CELL CHANGE

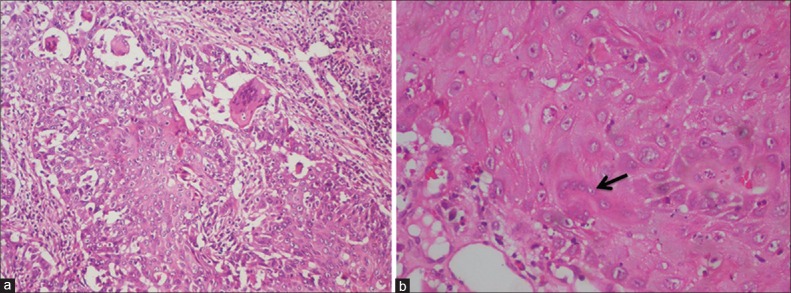

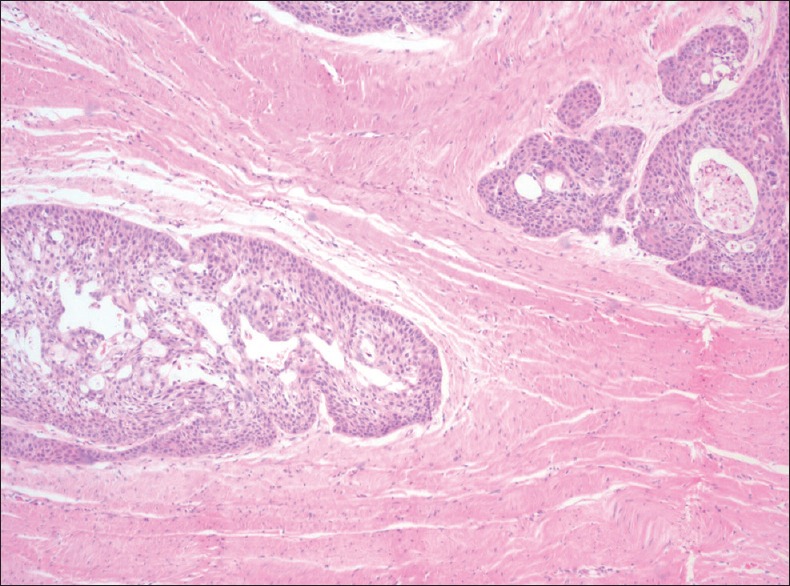

Clear squamous cells are characterized by empty appearing or “bubbled” cytoplasm. Clear cells in OSCC were first described by Kuo in 1980. He described it to be a degenerative phenomenon, whereas some of the recent studies have demonstrated glycogen accumulations in the cytoplasm of clear cells. The content of the clear cells has to be confirmed using special stains. The presence of glycogen in the cells predicts unfavourable prognosis as it suggests aggressiveness in the tumour cells whereas degenerative phenomenon predicts better prognosis as the cells are about to degenerate[6,7] [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph showing clear cell change in oral squamous cell carcinoma tumour islands (H&E stain, ×40)

EPITHELIAL-MESENCHYMAL TRANSITION

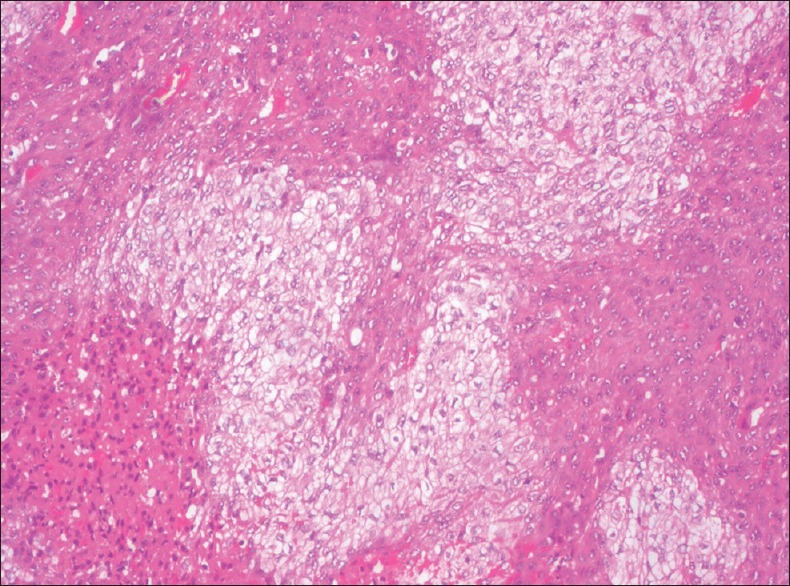

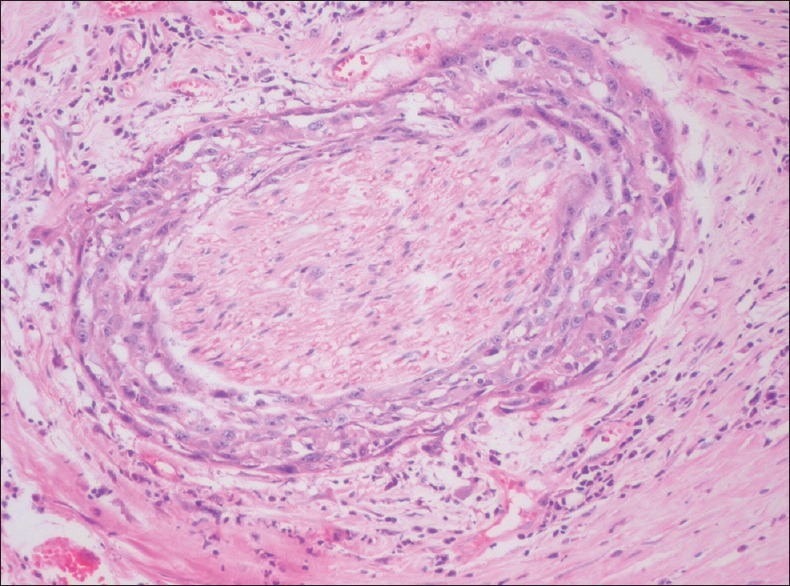

EMT is the process by which epithelial cells acquire a mesenchymal phenotype or fibroblast-like property involving reorganization of their cytoskeleton followed by breaking out connections with the adjacent cells. Once the transition process is complete, the cells dissolve the extracellular matrix and spread to the surrounding tissues. The process of EMT is linked with cancer cell metastasis and invasion, which directly correlates with poor prognosis[8] [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph showing epithelial-mesenchymal transition of the tumour cells (H&E stain, ×200)

STROMAL DESMOPLASIA

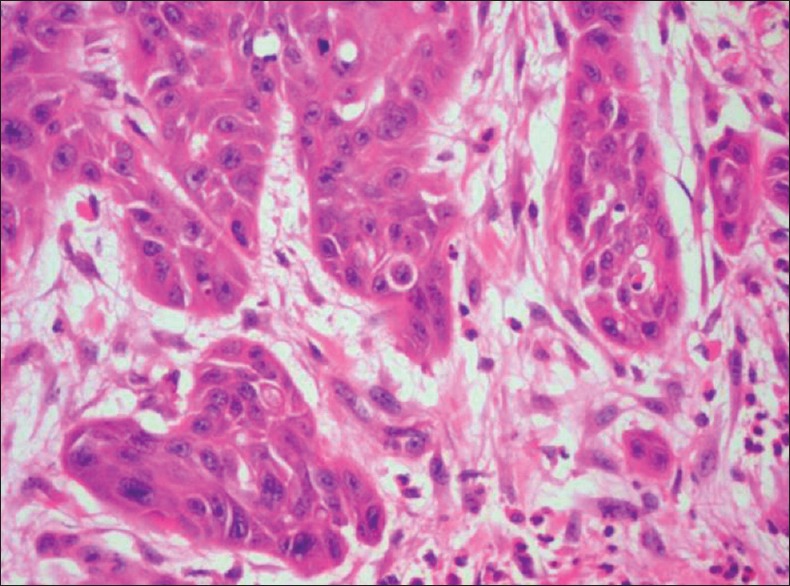

Stromal desmoplasia is defined as the response of host cells to inductive stimuli exerted by tumour cells. In response to this the host stromal cells produce collagen and extracellular proteins regarded as stromal desmoplasia. The biological relevance of the desmoplastic host reaction is not fully understood. Previously, it was recommended that desmoplasia plays a protective role and borders the process of tumour invasion. Recently, evidences suggest that molecular crosstalk between neoplastic cells and stromal cells, and cancer induced changes in the stroma, modify the differentiation, proliferative capacity and invasive capacity of tumour cells.[9] Tumour desmoplasia occurs in highly developed invasive tumours of OSCC[10] [Figure 3]. The collagen and extracellular matrix proteins secreted by stromal cells initiates the desmoplastic retort to arbitrate the invasion process.[10]

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph of oral squamous cell carcinoma showing desmoplasia in the tumour stroma (H&E stain, ×40)

STROMAL HYALINIZATION

Homogenous eosinophilic condensation of collagen with less number of cells characterizes stromal hyalinization. It is an attempt by the host cells to wall-off the invasive tumour cells [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph of oral squamous cell carcinoma showing stromal hyalinization (H&E stain, ×40)

NEURAL INVASION

The incidence of perineural invasion (PNI) in head and neck cancers is as high as 80% and about 31% of OSCC cases show perineural invasion which is characterized by presence of tumour cells in the perineural space [Figure 5]. The various patterns of PNI include complete encirclement, incomplete “crescent-like” encirclement, sandwiching “onion skin,” partial invasion and neural permeation. It is a form of tumour spread exhibited by neurotropic malignancies that correlate with aggressive behaviour, disease recurrence and increased morbidity and mortality. PNI is due to tropism of tumour cells for nerve bundles in the surrounding stroma, a feature seen either in intra/extra tumoral areas.[11,12]

Figure 5.

Photomicrograph showing perineural invasion by tumour cells of oral squamous cell carcinoma (H&E stain, ×200)

VASCULAR INVASION

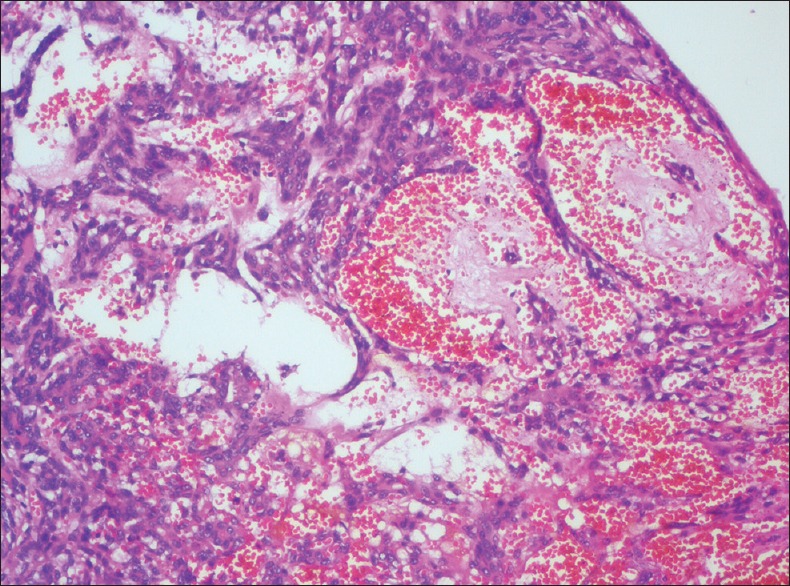

It is defined by the presence of tumour cells in the vascular spaces [Figure 6] and about 17.2% of OSCC cases show vascular invasion. Studies have shown that vascular invasion is significantly associated with increased death rates at 5-year follow up.[11,13]

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph showing vascular invasion by tumour cells (H&E stain, ×100)

TISSUE EOSINOPHILIA

Tumour associated tissue eosinophila is intense and seems to reflect the stromal invasion of OSCCs that occur in advanced clinical stage. However, various studies suggest that tumour eosinophila showed no prognostic value in relation to 5-year or 10-year survival rate of OSCC[14] [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Photomicrograph showing tissue eosinophilia (H&E stain, ×400)

GIANT CELLS

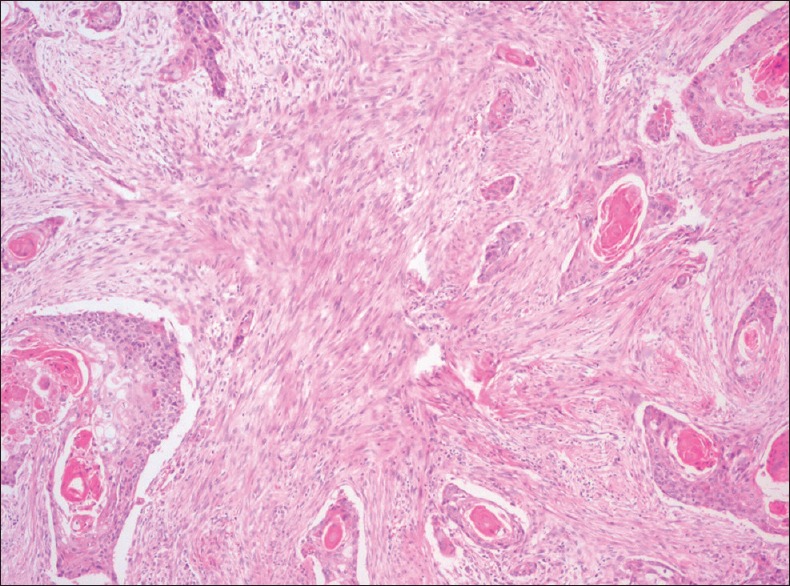

Giant cells in OSCC can be detected as a result of foreign body reaction to keratin or due to the formation of malignant tumour giant cells in poorly differentiated carcinomas. The foreign body giant cells [Figure 8] tend to locate in the vicinity of devitalized and keratinized tumour tissue and are believed to serve a resorptive function. Moreover, areas of extensive keratinization demonstrate large keratin granulomas. These foreign body giant cells are thought to originate from monocyte-macrophage system and are CD68 positive.

Figure 8.

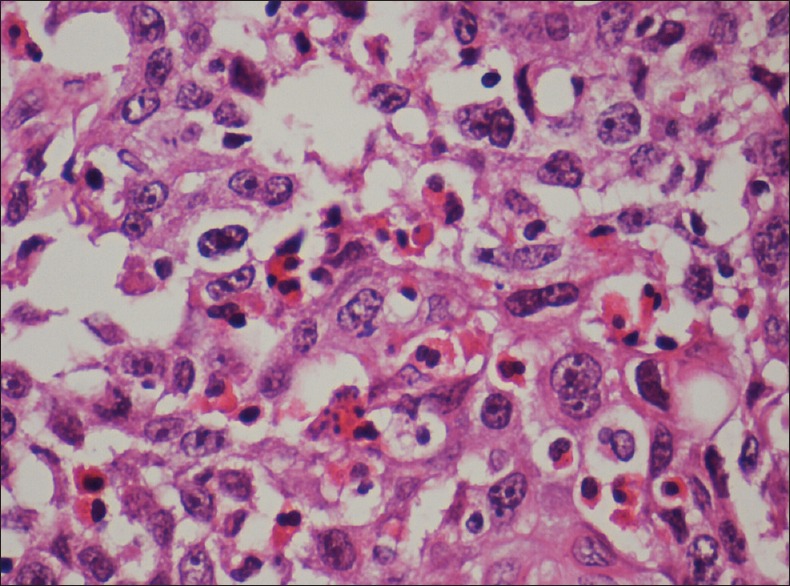

Photomicrograph showing (a) Foreign body giant cells (H&E stain, ×100) and (b) Tumour giant cells (H&E stain, ×400)

Malignant tumour giant cells are formed by fusion of small tumour cells or arrest in G1 phase of cell division of the tumour cells leading to incomplete DNA synthesis and accumulation of energy substrates. This results in enlargement of cells. Such giant cells can re-enter cell cycle with incomplete division causing multinucleation and polyploidization. The giant cells exhibiting pleomorphism of the nuclei predicts bad prognosis of the tumour.[15,16,17]

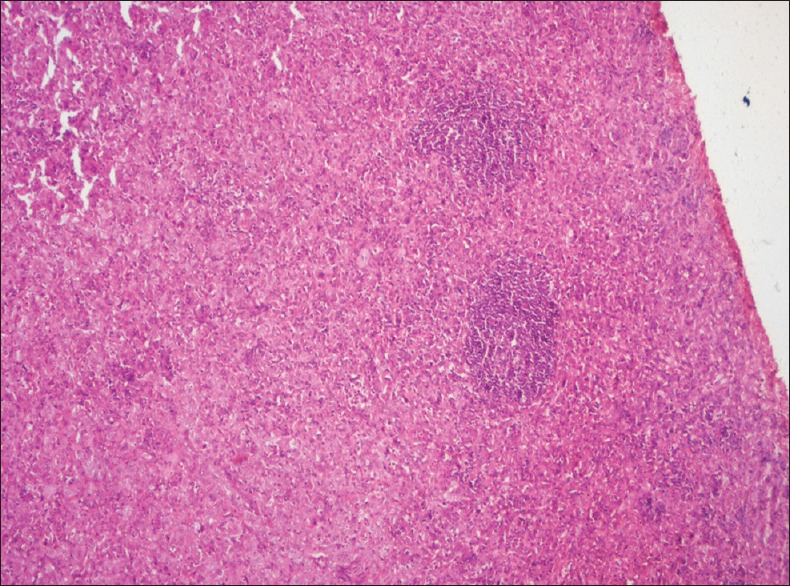

TERTIARY LYMPHOID FOLLICLES

The immune cells infiltrating into the sites of chronic inflammation organize themselves both anatomically and functionally similar to secondary lymphoid organs. It consists of B-cells, follicular dendritic cells and T-cells, and is termed as tertiary lymphoid structures. These have been detected in about 21% of oral cancers and have been found to be positive prognostic predictors for a patient with OSCC [Figure 9]. The tertiary lymphoid strucutres (TLSs) are chiefly found in the peri-tumoural stroma within 0.5 mm distance from the tumour front, in lymphocyte rich areas.[18]

Figure 9.

Photomicrograph showing tertiary lymphoid follicles among inflammatory cells and tumor cells (H&E stain, ×40)

CONCLUSION

Although easily diagnosed, certain histopathological features in conventional OSCC gives us a clue to assess the severity of the case even after it has been diagnosed as well differentiated OSCC. Thus tumours of the same clinical stage may respond differently to the same treatment and may also have distinct clinical tertiary outcomes. Features such as lymphoid follicle formation predicts better prognosis for the patient, whereas features such as EMT, neural invasion, vascular invasion and desmoplasia predicts poor prognosis. This article attempts to present some of the infrequent histopathological features that are uncommon in conventional OSCC.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Varshitha A. Prevalence of Oral Cancer in India. J Pharm Sci and Res. 2015;7(10):845–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes L. Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. 3rd ed. Vol 1. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. Missouri: Saunders, Elsevier; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson L.D.R. Mini-Symposium: Head and neck Pathology: Squamous cell carcinoma variants of the head and neck. Curr Diagn Pathol. 2003;9:384–96. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markwell SM, Weed SA. Tumour and Stromal-Based Contributions to Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Invasion. Cancer. 2015;7:382–406. doi: 10.3390/cancers7010382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nazir H, Salroo IN, Mahadesh J, Laxmidevi BL, Shafi M, Pillai A, et al. Clear Cell Entities of the Head and Neck: A Histopathological Review. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences. 2015;14(6):125–35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Margaritescu I, Chirita AD. Clear Cell and Signet-Ring Cell Squamous Cell Carcinoma. In: Rongioletti F, Magaristescu I, Smoller BR, editors. Rare Malignant Skin Tumours. 1st ed. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krisanaprakornkit S, Iamaroon A. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. ISRN Oncol. 2012;2012:681469. doi: 10.5402/2012/681469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sis B, Sarioglu S, Sokmen S, Sakar M, AKupelioglu, Fuzun M. Desmoplasia measured by computer assisted image analysis: An independent prognostic marker in colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:32–38. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.018705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawashiri S, Tanaka A, Noguchi N, Hase T, Nakaya H, Ohara T, et al. Significance of stromal desmoplasia and myofibroblast appearance at the invasive front in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Head and Neck. 2009;31:1346–53. doi: 10.1002/hed.21097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavalcante WS, Hsieh R, Lourenço SV, Godoy LM, De Souza LNG, Almeida-Coburn KL, et al. Neural and Vascular Invasions of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas. J Oral Hyg Health. 2015;3:187–94. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varsha BK, Radhika MB, Makarla S, Kuriakose MA, Satya Kiran GVV, Padmalatha GV. Perineural invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma: Case series and review of literature. J Oral MaxillofacPathol. 2015;19:335–14. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.174630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurtz KA, Hoffman HT, Zimmerman MB, Robinson RA. Perineural and Vascular Invasion in Oral Cavity Squamous Carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:354–59. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-354-PAVIIO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliveira DT, Tjioe KC, Assao A, Sita Faustino SE, Lopes Carvalho LA, et al. Tissue eosinophilia and its association with tumoural invasion of oral cancer. Int J Surg Pathol. 2009;17(3):244–9. doi: 10.1177/1066896909333778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patil S, Rao RS, Ganavi BS. A Foreigner in Squamous Cell Carcinoma! J Int Oral Health. 2013;5(5):147–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burkhardt A, Gebbers JO. Giant cell stromal reaction in squamous cell carcinoma. Virchow Arch A Path Anat and Histol. 1997;375:263–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00427058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horbay R, Stoika R. Giant cell formation: The way to cell death or cell survival? Cent Eur J Biol. 2011;6(5):675–84. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wirsing AM, Rikardsen OG, Steigen SE, Hansen LU, Olsen EH. Characterisation and prognostic value of tertiary lymphoid structures in oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Clinical Pathology. 2014:14–38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6890-14-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]