Abstract

Gitelman's syndrome is a rare genetic disease associated with chronic hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia and hypocalciuria. It requires lifelong supplementation with potassium and magnesium. Pregnancy management can be difficult and there are few published reports. Our case adds to the literature and illustrates some of the potential problems.

Keywords: endocrinology, maternal–fetal medicine

The diagnosis of Gitelman's syndrome was made in our patient when she presented with tiredness, muscle cramps and a brief episode of loss of consciousness. Her only sibling also had the syndrome and had died suddenly probably due to the condition.

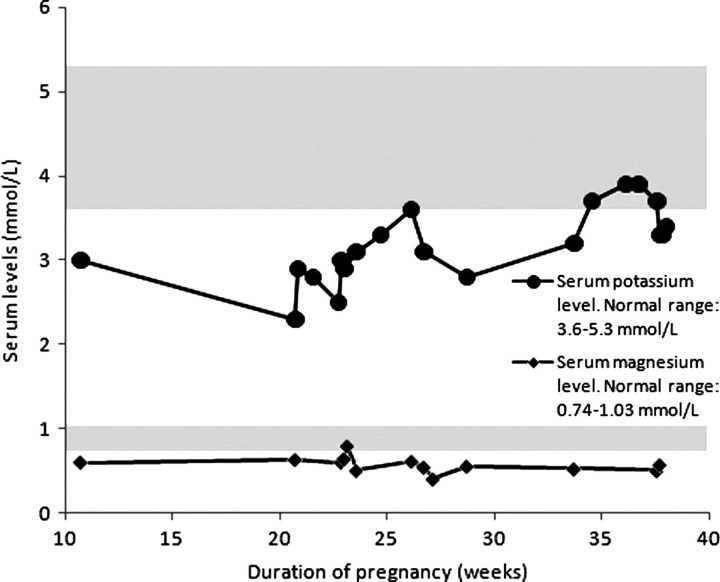

Five years after diagnosis our patient conceived for the first time at age 27. She presented to the joint obstetric–endocrine clinic at 11 weeks gestation. At that time she was taking 10 mg amiloride, 72 mmol potassium and 1500 mg magnesium per day. Serum potassium, magnesium and adjusted calcium levels were 3.0 mmol/L (normal range 3.6–5.5 mmol/L), 0.60 mmol/L (0.74–1.03 mmol/L) and 2.53 mmol/L (2.2–2.6 mmol/L), respectively. By 20 weeks gestation her serum potassium had fallen to 2.3 mmol/L. She was admitted for intravenous potassium supplementation and her oral potassium was increased to 144 mmol per day, which she continued until delivery. Despite this supplementation her potassium and magnesium levels remained below the normal range (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Serum magnesium and potassium levels during pregnancy

At 28 weeks gestation our patient was diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus. Control of her blood sugar levels was achieved by diet alone. An ultrasound examination at 34 weeks gestation suggested fetal macrosomia (fetal abdominal circumference on the 97th centile) with normal liquor volume. Delivery by caesarean section was advised to avoid the small but potentially serious risk of electrolyte disturbance during labour and/or maternal or fetal trauma associated with fetal macrosomia. The procedure was performed two weeks before the estimated date of delivery because the patient was becoming increasingly anxious she would die unexpectedly like her sister. The caesarean section was performed under general anaesthesia after failure to achieve an effective spinal anaesthetic. There were no surgical complications and a male child weighing 3.08 kg was born in good condition. There were no postoperative complications and mother and son were discharged home three days after delivery. Four weeks postdelivery the patient's potassium level was 3.3 mmol/L and her magnesium level had increased to within the normal range at 0.77 mmol/L.

DISCUSSION

Gitelman's syndrome is an autosomal recessive condition.1 The genetic defect is a mutation in the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl co-transporter encoded by the SLC12A3 gene. This results in chronic hypokalaemic metabolic alkalosis with salt wasting, hypomagnesaemia and hypocalciuria. The syndrome is often asymptomatic but may present with muscle weakness and tetany due to hypomagnesaemia. While regarded as a relatively benign condition, it can be complicated by sustained ventricular arrhythmia, seizure-like activity and persistent electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities.2 We consider it probable that an imbalance of electrolytes resulted in our patient's initial presentation with loss of consciousness and also in her sister's sudden death. A reduction in either serum potassium or magnesium concentrations can lengthen the action potential of myocytes, hence prolonging the QT interval, and thereby inducing ventricular arrhythmia with syncope or sudden death.2 The diagnosis of Gitelman's syndrome is by exclusion of other causes of electrolyte disturbance. It is related to Bartter's syndrome but has different clinical characteristics and biochemical markers as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Gitelman's and Bartter's syndromes

| Gitelman's syndrome | Bartter's syndrome | |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic defect | Autosomal recessive | Autosomal recessive |

| Area affected | Sodium-chloride co-transporter in the distal convoluted tubule | Chloride channel in the thick ascending loop of Henle |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Age at presentation | Early adulthood | Childhood |

| Severity of condition | Usually mild | Moderate to severe |

| Muscle cramps | Present | Absent |

| Tetany | May be present | Absent |

| Biochemical markers | ||

| Metabolic alkalosis | Present | Present |

| Serum potassium | Low | Low |

| Serum magnesium | Low | Normal or mildly reduced |

| Urinary prostaglandins | Normal | High |

| Urinary calcium | Low | High |

| Serum calcium | Normal | Normal |

To our knowledge, only 13 pregnancies in 11 women with Gitelman's syndrome have been reported.2–9 The aim in pregnancy is to normalize potassium and magnesium levels as much as possible so that patients remain asymptomatic.2–9 This can be extremely difficult 2 and requires frequent electrolyte measurements and sometimes multiple admissions.3 Hyperemesis and fetal demands on potassium can exacerbate already reduced levels of these electrolytes.4 Magnesium supplementation is often limited by gastrointestinal side-effects, but is necessary not only to correct the magnesium deficiency but also to normalize the potassium levels. Oral supplementation is usually sufficient but, as shown in our case and reported in previous literature, this may at times have to be supplemented by intravenous treatment. Of the 13 cases reported, six required intravenous potassium during pregnancy.3–6 However, complete normalization of serum potassium and magnesium is not essential for a good obstetric outcome.2

Patients with Gitelman's syndrome require lifelong potassium and magnesium supplements and often also potassium-sparing diuretics. Table 2 illustrates the common medications used to regulate electrolyte levels in Gitelmans' syndrome. Data on safety in pregnancy are limited, hence their use for maternal benefit must be balanced against possible ill-defined fetal risks. Possible aberrations in amniotic fluid volume have been described in the literature and usually present as oligohydramnios.3,5–8 This may be linked to the use of spironolactone.7 Monitoring of liquor volume during pregnancy is advised.2 We suggested to our patient to continue amiloride throughout pregnancy as it was so difficult to maintain her potassium level with supplements alone.

Table 2.

Common medication used in Gitelman's syndrome

| Pregnancy | Breast-feeding | Side-effects | Dosing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amiloride | Manufacturers advise caution, no information | Manufacturers advise avoid, no information | Gastro-intestinal disturbances | Start with 5–10 mg OD. Max dose 20 mg daily |

| Spironolactone | Feminization of female fetus in animal studies. Evidence of human fetal risks but benefits may outweigh risks | Metabolites present in milk, but amount probably too small to be harmful | Gastro-intestinal disturbances | 100–200 mg daily, increased to 400 mg if required |

| Eplerenone | Manufacturer advises caution, no information available | Manufacturer advises use only if potential benefit outweighs risks | Diarrhoea, nausea, hypotension, hyperkalaemia | Initially 25 mg OD, increased within 4 weeks to 50 mg OD |

The mode of delivery in Gitelman's syndrome should be determined by obstetric considerations. During labour and delivery, the administration of intravenous fluids should be closely monitored and electrolyte levels measured every 4–6 hours in order to minimize the risk of electrolyte imbalance. Six of the 13 cases described in the literature were delivered by caesarean section. 3,5–7,9 Of the seven women who delivered vaginally, no specific complications were described during labour. The overall outcomes for fetus and mother were favourable in all 13 cases. Our patient was delivered by an elective caesarean section at 37+5 weeks, partly for obstetric reasons (gestational diabetes with suspected fetal macrosomia and the potential for electrolyte imbalance if labour was prolonged) and partly for maternal anxiety. In the event, the baby's birth weight was on the 50th centile. There is little published data on anaesthetic management of Gitelman's syndrome in pregnancy. Preoperative assessment with ECG, electrolyte level optimization and awareness of potential complications associated with hypokalaemia and hypomagnesaemia (laryngeal spasm, convulsions and ventricular arrhythmias) is important.9 For delivery, a regional anaesthetic technique is preferred.9

Postpartum women should be followed up with at least once-weekly electrolyte measurements as levels of potassium and magnesium can change considerably and tend to rise. The adjustments in medication made during pregnancy will often have to be reversed. Electrolyte and genetic testing in the infant should be discussed with the parents.

In conclusion, pregnancy with Gitelman's syndrome presents challenges in management as electrolyte control may be very difficult. Close liaison within a multidisciplinary team including obstetricians, endocrinologists, anaesthetists, neonatologists and geneticists is of paramount importance for good obstetric and neonatal outcomes.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shaer AJ. Inherited primary renal tubular hypokalemic alkalosis: a review of Gitelman and Bartter syndromes. Am J Med Sci 2001;36:310–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Basu A, Dillon RDS, Taylor R, Davidson JM, Marshall SM. Is normalisation of serum potassium and magnesium always necessary in Gitelman syndrome for a successful obstetric outcome? BJOG 2004;111:630–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McCarthy FP, Magee CN, Plant WD, Kenny LC. Gitelman's syndrome in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Nephrol Dial Transpl 2010;25:1338–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Srinivas SK, Sukhan S, Elovitz MA. Nausea, emesis and muscle weakness in a pregnant adolescent. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:481–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Daskalakis G, Marinopoulos S, Mousiolis A, Mesogitis S, Papantoniou N, Antsaklis A. Gitelman syndrome-associated severe hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia: case report and review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2010;23:1301–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Haan J, Geers T, Berghput A. Gitelman syndrome in pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2008;103:69–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. De Arriba G, Sanchez-Heras M, Basterrechea MA. Gitelman syndrome during pregnancy: a therapeutic challenge. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009;280:807–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jones JM, Dorrell S. Outcome of two pregnancies in a patient with Gitelman's syndrome – a case report. J Matern Fetal Invest 1998;8:147–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shanbhag S, Neil J, Howell C. Anaesthesia for caesarean section in a patient with Gitemaln's syndrome. Int J Obstet Anesth 2010;19:451–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]