Abstract

Objective

To analyse the dose-dependent effect of body mass index (BMI) categories for common pregnancy outcomes.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study of all deliveries that occurred between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2009 in a tertiary maternity centre, in Sydney Australia. Common pregnancy outcomes were analysed against World Health Organization (WHO) BMI categories using multiple logistic regression analysis.

Results

From a total of 18,304 pregnancies, 9087 singleton pregnancies with complete data-sets were identified. Of these pregnancies, 4000 (44%) had a normal BMI, 470 (5.2%) were underweight, 2293 (25.2%) were overweight, 1316 (14.5%) were obese class I, 630 (6.9%) were obese class II and 378 (4.2%) were obese class III. Using the normal BMI category as the reference, there was a clear dose effect of BMI categories for hypertension (P < 0.001), pre-eclampsia (P < 0.001), caesarean section (P < 0.001), macrosomia (P < 0.001), large for gestational age (P < 0.001), small for gestational age (P < 0.001) and neonatal respiratory distress (P = 0.039). In contrast, despite a significant association with BMI (P < 0.001), a dose-dependent effect was not found for gestational diabetes.

Conclusion

The results of our study have important clinical significance as the data, using WHO BMI categories, more accurately help stratify risk assessment in a clinically relevant dose-dependent relationship.

Keywords: pregnancy outcome, body mass index, World Health Organization

INTRODUCTION

The rates of overweight and obesity have been increasing over the last few decades, and have become a growing concern with respect to the health and wellbeing of patients. According to World Health Organization (WHO), in developed countries 35–60% of women who are of reproductive age are either overweight or obese.1 Furthermore, in the 2004–2005 Australian Bureau of Statistics Health Survey, 54% of Australians were classified as overweight or obese and, of the female population, 45% of women were in this classification. In comparison, the 1989–1990 Health Survey reported that only 38% of the total population and 32% of women were classified as overweight or obese.2

In light of this increasing trend of overweight and obesity there has been growing interest in the obstetric community to determine how maternal weight affects pregnancy outcomes for both the mother and neonate. Various studies have demonstrated a correlation between increasing maternal weight and adverse pregnancy outcomes, using body mass index (BMI) as a standard of measurement.3–16 There has been evidence of an increasing association between women with a higher BMI and maternal pregnancy outcomes such as pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH), pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes and caesarean section delivery.3–8 Although the associations between increasing BMI and maternal outcomes have been consistent across international studies, there is conflicting evidence with respect to neonatal outcomes. Some studies have shown an association between women who were overweight or obese and respiratory distress syndrome, large for gestational age (LGA), macrosomia, meconium aspiration syndrome, stillbirth, neonatal hypoglycaemia, prematurity and admission to neonatal intensive care unit.3–13 Conversely, others have shown a decreasing or lack of association between increasing BMI and prematurity,5,8,9 and no association with hypoglycaemia, respiratory distress syndrome, birth defects and stillbirth.8,9 Similarly, there is conflicting evidence regarding the association between underweight women and small for gestational age (SGA) neonates.6,7,14,15

The effect of BMI has been assessed both as a continuous variable and categorically; however, the defined BMI categories varied in range among the different studies, and others have assessed according to WHO-defined categories.12,13 The advantage of using WHO BMI categories is that it provides for an internationally accepted and standardized definition of weight categories, allowing for unequivocal comparison across studies of specified associations, whether with regard to pregnancy outcomes or other health-related outcomes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the association between maternal BMI, according to WHO BMI categories, on pregnancy outcomes in the context of an Australian population.

METHODS

Study design and setting

This was a retrospective cohort study of all deliveries that occurred between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2009 at a tertiary maternity service in western metropolitan Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Women were identified using the hospital's obstetric database. The information in the database is updated and maintained during and after pregnancy and contributes to statewide data collection.

Participants

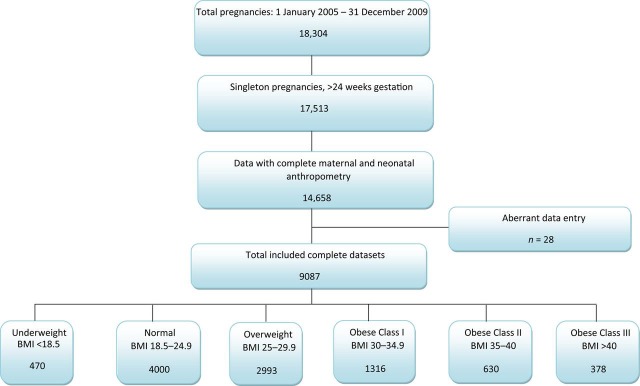

Over the study period there were 18,304 pregnancies, of which all singleton pregnancies greater than 24 weeks gestation were eligible for inclusion in the study (n = 17,513). Cases were excluded if the data were incomplete for maternal and neonatal anthropometric measurements (n = 2855), contained data entry errors (n = 28) or if the cases had incomplete data (n = 5543). Included cases were divided into six BMI categories, according to WHO definitions – underweight BMI < 18.5 kg/m2; normal BMI 18.5–24.99 kg/m2; overweight BMI 25–29.99 kg/m2; obese class I BMI 30–34.99 kg/m2; obese class II BMI 35–39.99 kg/m2 and obese class III BMI > 40 kg/m2 (Figure 1). BMI was calculated from the measured weight of the women, which was measured during the first antenatal visit.

Figure 1.

Study cohort

Variables

The following data were gathered from electronic medical records: antenatal and perinatal outcomes assessed included prelabour rupture of membranes (PROM); threatened preterm labour (TPL); antepartum haemorrhage (APH); pregnancy-induced hypertension and pre-eclampsia;16 gestational diabetes (GDM)17 and caesarean section delivery. Neonatal outcomes that were assessed included macrosomia; SGA;18 LGA; prematurity; respiratory distress and other neonatal outcomes, which were unspecified. Adverse fetal outcomes such as pregnancy loss and major malformations leading to therapeutic or spontaneous abortions could not be analysed due to the exclusion of cases less than 24 weeks of gestational age.

BMI was defined as the weight, in kilograms, divided by the square of the height, in metres. Macrosomia was defined as a birth weight >4000 g and prematurity was defined as a gestational age <37 weeks. Birth weight Z scores were calculated to identify neonates who were either SGA or LGA, which are defined as <10th percentile and >90th percentile, respectively. Z scores were controlled for infant gender, gestational age and parity, and were standardized for Australian population figures.19

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics are reported as means and standard deviations. Comparisons between all categorical measures were made using a chi-squared test. Significant differences in continuous variables between groups were tested using one-way analysis of variance. BMI was assessed both as a continuous variable and as categorical variables. The associations between BMI WHO categories and pregnancy outcomes were assessed using logistic regression modelling, whereas multiple linear regression was used when BMI was considered as a continuous variable. Both univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to control for potential confounders, such as maternal age, parity and smoking. Additionally, due to potential interactions, maternal outcomes were also controlled for including PIH, pre-eclampsia, GDM, APH, TPL and PROM. Neonatal outcomes were controlled for the above-listed maternal outcomes in addition to prematurity, macrosomia, LGA, SGA, respiratory distress, hypoglycaemia, hypothermia, suspected infection, birth defects and other neonatal outcomes that were not specified. Analyses were performed on outcomes with a prevalence of at least 1% to reduce the likelihood of imprecision. Statistical significance was defined as P value <0.05.

RESULTS

Overall, 9087 pregnancies were analysed in the study; all cases were divided into six BMI categories, according to WHO classifications. The normal BMI category was used as the reference group for analyses. Maternal baseline characteristics were compared for all BMI categories, and are listed in Table 1. There were no statistical differences in the proportion of male births between the different categories. However, women with higher BMI had a higher mean maternal age (P < 0.001), gestational length (P < 0.001) and had a greater parity (P < 0.001); conversely, there was a higher rate of smoking in underweight women (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics table

| BMI category | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <18.5 | 18.5–24.9 | 25–29.9 | 30–34.9 | 35–39.9 | >40 | Total | ||

| All women (%) | 470 (5.2) | 4000 (44.0) | 2293 (25.2) | 1316 (14.5) | 630 (6.9) | 378 (4.2) | 9087 | |

| Maternal age | 27 ± 5.7 | 28 ± 5.5 | 29 ± 5.2 | 29 ± 5.3 | 30 ± 5.3 | 30 ± 5.0 | 29 ± 5.4 | P < 0.001 |

| Parity | 1 ± 1.1 | 1 ± 1.3 | 2 ± 1.3 | 2 ± 1.4 | 2 ± 1.5 | 2 ± 1.4 | 2 ± 1.3 | P < 0.001 |

| Gestational age | 39.0 ± 1.7 | 39.4 ± 1.6 | 39.3 ± 1.6 | 39.4 ± 1.7 | 39.3 ± 1.6 | 39.3 ± 1.6 | 39 ± 1.6 | P < 0.001 |

| Smoking (%) | 198 (42.1) | 1007 (25) | 546 (23.8) | 338 (25.7) | 186 (29.5) | 82 (21.7) | 2357 | P < 0.001 |

| Male neonate (%) | 240 (51.1) | 2074 (51.9) | 1173 (51.2) | 707 (53.7) | 343 (54.4) | 199 (52.6) | 4736 | P = 0.557 |

| Maternal characteristics (%) | ||||||||

| Gestational diabetes | 29 (6.2) | 266 (6.7) | 209 (9.1) | 174 (13.2) | 104 (16.5) | 63 (16.6) | 845 (9.3) | |

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension | 4 (0.9) | 111 (2.8) | 132 (5.8) | 109 (8.3) | 70 (11.1) | 48 (12.7) | 474 (5.2) | |

| Pre-eclampsia | 2 (0.4) | 43 (1.1) | 53 (2.3) | 40 (3.0) | 28 (4.4) | 20 (5.3) | 186 (2.0) | |

| Antepartum haemorrhage | 18 (3.8) | 126 (3.2) | 51 (2.2) | 37 (2.8) | 11 (1.7) | 8 (2.1) | 251 (2.8) | |

| Threatened preterm labour | 25 (5.3) | 125 (3.1) | 64 (2.8) | 31 (2.3) | 21 (3.3) | 5 (1.3) | 271 (3.0) | |

| Prelabour rupture of membranes | 13 (2.8) | 91 (2.3) | 52 (2.3) | 27 (2.1) | 14 (2.2) | 6 (1.6) | 203 (2.2) | |

| Caesarean section | 100 (21.3) | 952 (23.8) | 672 (29.3) | 428 (32.5) | 233 (37.0) | 176 (46.7) | 2561 (28.1) | |

| Neonatal characteristics (%) | ||||||||

| Birth weight (g) | 3183 ± 505 | 3407 ± 517 | 3484 ± 542 | 3543 ± 564 | 3585 ± 530 | 3664 ± 557 | 3458 ± 541 | P < 0.001 |

| Z score | −0.4 ± 1.1 | 0.02 ± 1.2 | 0.28 ± 1.3 | 0.4 ± 1.3 | 0.57 ± 1.3 | 0.78 ± 1.4 | 0.19 ± 1.3 | P < 0.001 |

| Prematurity | 39 (8.3) | 187 (4.7) | 134 (5.8) | 75 (5.7) | 42 (6.7) | 13 (3.4) | 490 (5.4) | |

| Macrosomia | 22 (4.7) | 446 (11.2) | 373 (16.3) | 271 (20.6) | 132 (21.0) | 94 (24.9) | 1338 (14.7) | |

| Large for gestational age | 12 (2.6) | 337 (8.4) | 329 (14.3) | 214 (16.3) | 133 (21.1) | 84 (22.2) | 1109 (12.2) | |

| Small for gestational age | 63 (13.4) | 278 (7.0) | 150 (6.5) | 68 (5.2) | 25 (4.0) | 10 (6.4) | 594 (6.5) | |

| Respiratory distress | 20 (4.3) | 117 (2.9) | 88 (3.8) | 55 (4.2) | 32 (5.1) | 21 (5.6) | 333 (3.7) | |

| Other neonatal complications | 24 (5.1) | 131 (3.3) | 85 (3.7) | 52 (4.0) | 20 (3.2) | 11 (2.9) | 323 (3.6) | |

BMI, body mass index

The results of the unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses for antenatal and perinatal outcomes and their relationship with BMI are detailed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. There was a highly significant (P < 0.001) positive association with PIH, pre-eclampsia, GDM and caesarean section, when BMI was analysed as both a categorical and continuous variable. This association was present before and after adjustment for confounders. Interestingly, despite evidence of an association between BMI and TPL for unadjusted analyses, this association was lost after controlling for confounders. There was no evidence of an association between BMI and APH or PROM.

Table 2.

Unadjusted perinatal and antenatal outcomes

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension | Pre-eclampsia | Gestational diabetes | Antepartum haemorrhage | Threatened preterm labour | Prelabour rupture of membranes | Caesarean section | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI category* | ||||||||

| < 18.5 | OR | 0.301 (0.11–0.82) | 0.393 (0.10–1.63) | 0.923 (0.62–1.37) | 1.224 (0.74–2.03) | 1.742 (1.12–2.71) | 1.222 (0.68–2.20) | 0.865 (0.69–1.09) |

| 25–29.9 | OR | 2.140 (1.65–2.77) | 2.177 (1.45–3.27) | 1.408 (1.17–1.70) | 0.699 (0.50–0.97) | 0.890 (0.66–1.21) | 0.997 (0.71–1.41) | 1.327 (1.18–1.49) |

| 30–34.9 | OR | 3.164 (2.41–4.15) | 2.885 (1.87–4.46) | 2.139 (1.75 - 2.62) | 0.889 (0.61–1.29) | 0.748 (0.50–1.11) | 0.900 (0.58–1.39) | 1.543 (1.35–1.77) |

| 35–39.9 | OR | 4.380 (3.21–5.98) | 4.280 (2.64–6.94) | 2.775 (2.17–3.54) | 0.546 (0.29–1.02) | 1.069 (0.67–1.71) | 0.976 (0.55–1.73) | 1.879 (1.57–2.24) |

| > 40 | OR | 5.096 (3.57–7.28) | 5.141 (2.99–8.83) | 2.808 (2.09–3.78) | 0.665 (0.32–1.37) | 0.416 (0.17–1.02) | 0.693 (0.30–1.59) | 2.790 (2.25–3.46) |

| P value† | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.089 | 0.013 | 0.906 | <0.001 | |

| BMI (continuous variable) | OR | 1.081 (1.07–1.09) | 1.073 (1.06–1.09) | 1.053 (1.04–1.06) | 0.970 (0.95–0.99) | 0.973 (0.95–0.99) | 0.986 (0.96–1.01) | 1.043 (1.04–1.05) |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.204 | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index, OR, odds ratio

95% Confidence intervals in parentheses

*Reference group was normal BMI (18.5–24.9)

†Overall heterogeneity across BMI categories

Table 3.

Adjusted perinatal and antenatal outcomes (adjusted for maternal age, parity, smoking, gestational age, PIH, pre-eclampsia, GDM, APH, TPL, PROM)

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension | Pre-eclampsia | Gestational diabetes | Antepartum haemorrhage | Threatened preterm labour | Prelabour rupture of membranes | Caesarean section | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI category* | ||||||||

| < 18.5 | OR | 0.307 (0.11–0.84) | 0.375 (0.09–1.58) | 0.912 (0.61–1.36) | 1.005 (0.60–1.69) | 1.424 (0.87–2.32) | 0.748 (0.37–1.53) | 0.811 (0.64–1.03) |

| 25–29.9 | OR | 2.148 (1.66–2.79) | 2.027 (1.32–3.12) | 1.324 (1.09–1.60) | 0.710 (0.51–1.00) | 0.897 (0.64–1.26) | 0.942 (0.62–1.44) | 1.304 (1.16–1.47) |

| 30–34.9 | OR | 3.430 (2.60–4.52) | 3.323 (2.10–5.26) | 2.088 (1.70–2.57) | 0.940 (0.64–1.38) | 0.718 (0.46–1.12) | 0.775 (0.44–1.36) | 1.626 (1.41–1.88) |

| 35–39.9 | OR | 4.970 (3.62–6.83) | 5.517 (3.29–9.26) | 2.649 (2.06–3.41) | 0.566 (0.30–1.08) | 1.199 (0.72–2.01) | 1.205 (0.62–1.34) | 1.967 (1.63–2.37) |

| > 40 | OR | 5.760 (3.99–8.31) | 6.354 (3.50–11.53) | 2.648 (1.95–3.60) | 0.776 (0.37–1.64) | 0.466 (0.17–1.26) | 1.149 (0.43–3.04) | 3.078 (2.45–3.86) |

| P value† | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.266 | 0.14 | 0.848 | <0.001 | |

| BMI (continuous variable) | OR | 1.089 (1.08–1.10) | 1.088 (1.07–1.11) | 1.051 (1.04–1.06) | 0.978 (0.96–1.00) | 0.982 (0.96–1.01) | 1.007 (0.98–1.04) | 1.048 (1.04–1.06) |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.051 | 0.123 | 0.635 | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index; OR, odds ratio; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension; GDM, gestational diabetes; APH, antepartum haemorrhage; TPL, threatened preterm labour; PROM, prelabour rupture of membranes

95% Confidence intervals in parentheses

*Reference group was normal BMI (18.5–24.9)

†Overall heterogeneity across BMI categories

The results of the unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses for neonatal outcomes are listed in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. There was evidence of significant positive associations between BMI, both as a categorical and continuous variable, and macrosomia, LGA and respiratory distress, in both adjusted and unadjusted analyses. Similarly, there was a significant negative association between BMI and SGA, for both unadjusted and adjusted analyses. Despite a significant negative association with categorical BMI and prematurity (P = 0.004), there was no evidence of an association after controlling for confounders (P = 1.000). There was no evidence of an association between BMI and other neonatal outcomes.

Table 4.

Unadjusted neonatal outcomes

| Prematurity | Macrosomia | Large for gestational age | Small for gestational age | Respiratory distress | Other neonatal complications | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI category* | |||||||

| < 18.5 | OR | 1.845 (1.29–2.64) | 0.391 (0.25–0.61) | 0.285 (0.16–0.51) | 2.072 (1.55–2.78) | 1.475 (0.91–2.394) | 1.589 (1.02–2.48) |

| 25–29.9 | OR | 1.266 (1.01–1.59) | 1.548 (1.34–1.80) | 1.821 (1.55–2.14) | 0.937 (0.76–1.15) | 1.325 (1.00–1.76) | 1.137 (0.86–1.50) |

| 30–34.9 | OR | 1.232 (0.94–1.62) | 2.067 (1.75–2.44) | 2.111 (1.76–2.54) | 0.730 (0.56–0.96) | 1.45 (1.04–2.01) | 1.215 (0.88–1.69) |

| 35–39.9 | OR | 1.456 (1.03–2.06) | 2.112 (1.70–2.62) | 2.909 (2.33–3.63) | 0.553 (0.36–0.84) | 1.776 (1.19–2.65) | 0.968 (0.60–1.56) |

| > 40 | OR | 0.726 (0.41–1.29) | 2.637 (2.05–3.40) | 3.106 (2.38–4.06) | 0.364 (0.19–0.69) | 1.952 (1.21–3.15) | 0.885 (0.47–1.65) |

| P value† | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.343 | |

| BMI (continuous variable) | OR | 0.996 (0.98–1.01) | 1.053 (1.05–1.06) | 1.064 (1.05–1.07) | 0.949 (0.94–0.96) | 1.025 (1.01–1.04) | 0.994 (0.98–1.01) |

| P value | 0.549 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.46 |

BMI, body mass index; OR, odds ratio

95% Confidence intervals in parentheses

*Reference group was normal BMI (18.5–24.9)

†Overall heterogeneity across BMI categories

Table 5.

Adjusted neonatal outcomes (adjusted for maternal age, parity, smoking, gestational age, PIH, pre-eclampsia, GDM, APH, TPL, PROM, caesarean section, prematurity, macrosomia, LGA, SGA, respiratory distress, hypoglycaemia, hypothermia, suspected infection, birth defect and other neonatal complications)

| Prematurity | Macrosomia | Large for gestational age | Small for gestational age | Respiratory distress | Other neonatal complications | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI category* | |||||||

| < 18.5 | OR | 1.410 (∞) | 0.498 (0.32–0.78) | 0.306 (0.17–0.55) | 1.775 (1.32–2.40) | 1.330 (0.80–2.22) | 1.184 (0.73–1.93) |

| 25–29.9 | OR | 0.985 (∞) | 1.594 (1.37–1.86) | 1.746 (1.48–2.06) | 0.893 (0.724–1.103) | 1.272 (0.94–1.72) | 1.026 (0.76–1.39) |

| 30–34.9 | OR | 0.865 (∞) | 2.056 (1.73–2.45) | 2.027 (1.68–2.45) | 0.666 (0.50–0.88) | 1.380 (0.97–1.96) | 1.114 (0.77–1.60) |

| 35–39.9 | OR | 1.520 (∞) | 2.287 (1.82–2.88) | 2.790 (2.22–3.51) | 0.447 (0.29–0.69) | 1.763 (1.14–2.72) | 0.879 (0.52–1.49) |

| > 40 | OR | 0.626 (∞) | 2.793 (2.13–3.66) | 2.774 (2.11–3.65) | 0.312 (0.16–0.60) | 1.992 (1.19–3.34) | 0.925 (0.47–1.83) |

| P value† | 1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.039 | 0.942 | |

| BMI (continuous variable) | OR | 0.998 (∞) | 1.054 (1.05–1.06) | 1.060 (1.05–1.07) | 0.944 (0.93–0.96) | 1.028 (1.01–1.05) | 0.996 (0.98–1.02) |

| P value | 1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.687 |

BMI, body mass index; OR, odds ratio; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension; GDM, gestational diabetes; APH, antepartum haemorrhage; TPL, threatened preterm labour; PROM, prelabour rupture of membranes; LGA, large for gestational age; SGA, small for gestational age; ∞, the associations between neonatal outcomes and BMI were non-significant when adjusting for confounders.

95% Confidence intervals in parentheses

*Reference group was normal BMI (18.5–24.9)

†Overall heterogeneity across BMI categories

DISCUSSION

Key results

The results of our study are the first to demonstrate odds ratios for the relationship of pregnancy-related outcomes and BMI according to WHO categorization in an Australian population. The main findings of the study included evidence of a positive dose–response relationship between BMI categories and PIH, pre-eclampsia, caesarean sections, macrosomia, LGA infants and respiratory distress, as well as a negative dose response relationship between BMI categories and SGA infants. Interestingly, despite a positive relationship between increasing BMI categories and gestational diabetes, in class II and class III BMI categories, there was a plateau in the effect of BMI on GDM. The plateau in the association between class II and class III BMI categories has not been previously demonstrated. This may be due to variations in the definition of BMI categories, for example, overweight BMI 25–30 kg/m2, obese BMI > 30 kg/m2 and morbidly obese BMI > 40 kg/m2,4,6,8 or simply using overweight BMI 25–30 kg/m2 and obese BMI > 30 kg/m2.3 With respect to neonatal outcomes, few studies have assessed the impact of maternal BMI on individual neonatal outcomes.3,5,9 Our results show evidence of a parabolic association between BMI categories and respiratory distress, after controlling for both maternal and neonatal confounders, compared with studies that have shown no association9 or an association only with overweight women3 and occurrence of respiratory distress.

Limitations of the study

The data used for the study were extracted from a database, and the accuracy of the analyses is dependent upon the accuracy of the data entry. As was evident from Figure 1, data had to be excluded due to the presence of aberrant data, and thus the question arises as to the accuracy of other data entries, which were not recognized as aberrant. Additionally, a considerable number of cases were excluded from the study due to incomplete and missing data. The overall trends of the excluded group are similar to those of the included group. However, there were greater rates of outcomes that occurred across all BMI categories in the excluded group in comparison to the included group. Further analyses of the included and excluded groups demonstrated that the average booking date for the included group was 20 weeks gestation, whereas the excluded group had an average booking date at 27 weeks of gestation. This suggests that the women in the excluded group were presenting to the hospital at a later gestation, perhaps as a result of development of complication during their pregnancy for which they were referred from outer-regional hospitals or from the community, for tertiary care. Data entry for these acute presentations was generally incomplete and less reliable. Despite this exclusion, the overall outcomes are similar to other published data.4,5,8 However, this study was not designed to address epidemiological information but rather to analyse the association between BMI categories and pregnancy outcomes.

During the analyses attempts were made to control for as many confounders as possible, for example, maternal age, smoking, parity, PIH and GDM.20–22 However, despite the known effects that it has on pregnancy outcomes,23 ethnicity could not be controlled for. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1–3% of the population in this region is aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.24 At the booking antenatal visit, ethnicity is self-reported. It is important to consider that there is much diversity between and within aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities,25 and this should be taken into consideration in future studies.

To overcome these limitations and possible sources of bias in future database-dependent studies, prospective studies which ensure that databases cannot be terminated without complete data entry would be ideal.

CONCLUSION

Our study was able to demonstrate associations between BMI, according to WHO classification, and pregnancy-related outcomes with respect to both mother and neonate, in the context of an Australian population. In addition, our study found evidence of an association between respiratory distress that had not been demonstrated before, as well as evidence of a plateau in the likelihood of occurrence of gestational diabetes in class II and class III obese women, which had also not been demonstrated in previous studies. The value of the study is in the demonstration of associations according to internationally standardized BMI categories, according to the WHO. Thus, the results of our study are the first to facilitate assessment of risk for all WHO BMI categories. Our method of conducting the study using WHO-defined BMI categories allows for more clinically relevant risk stratification of patients. Future studies conducted in a similar manner would allow for equivalent comparison of associations, between ethnic groups and countries, not only pertaining to pregnancy-related outcomes but other health outcomes as well.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests: There are no conflicts of interest from any of the authors, who are alone responsible for the writing of this paper.

Funding: No funding was required for this study.

Ethical approval: The study received ethics approval by the Sydney West Area Health Service Human research ethics committee, Nepean Campus, on 16 June 2010. Project number 10/16.

Guarantor: RN.

Contributorship: KZ researched literature, gained ethical approval, conducted data analysis, wrote the draft manuscript and was involved in editing the manuscript. RN conceived the study and was involved in editing the manuscript. AL was involved in the editing of the manuscript. MM conducted data analysis. MP was involved in conceiving the study.

Acknowledgements: We would like to acknowledge Janet Long and Deborah Robinson for assisting in database extraction.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organisation (WHO). Global Database on Body Mass Index. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; See http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp (updated 18 May 2011; last checked 28 May 2011)

- 2. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Overweight and Obesity in Adults, Australia, 2004–2005. Australian Capital Territory, Australia: ABS; See http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats (updated 25 January 2008; last checked 18 May 2011)

- 3. Athukorala C, Rumbold AR, Willson KJ, Crowther CA. The risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women who are overweight or obese. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010;10:56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mantakas A, Farrell T. The influence of increasing BMI in nulliparous women on pregnancy outcome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2010;153: 43–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycaemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study: associations with maternal body mass index. BJOG 2010;117:575–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abenhaim HA, Kinch R, Morin K, Benjamin A, Usher R. Effect of prepregnancy body mass index categories on obstetrical and neonatal outcomes. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2007;275:39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heslehurst N, Simpson H, Ells LJ, et al. The impact of maternal BMI status on pregnancy outcomes with immediate short-tem obstetric resource implications: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2008;9:635–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khashan AS, Kenny LC. The effects of body mass index on pregnancy outcome. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:697–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Narchi H, Skinner A. Overweight and obesity in pregnancy do not adversely affect neonatal outcomes: new evidence. J Obstet Gynaecol 2010; 30:679–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reddy UM, Laughon SK, Sun L, Troendle J, Willinger M, Zhang J. Prepregnancy risk factors for antepartum stillbirth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1119–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chu SY, Kim SY, Lau J, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of stillbirth: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;197:223–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumari AS. Pregnancy outcome in women with morbid obesity. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2001;73:101–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sebire NJ, Jolly M, Wadsworth J, et al. Maternal Obesity and pregnancy outcome: a study of 287,213 pregnancies in London. Int Jf Obes 2001;25:1175–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kalk P, Guthmann F, Krause K, et al. Impact of maternal body mass index on neonatal outcome. Eur J Med Res 2009;14:216–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ronnenberg AG, Wang X, Xing H, et al. Low preconception body mass index is associated with birth outcome in a prospective cohort of Chinese women. J Nutr 2003;133:3449–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown MA, Hague WM, Higgins J, et al. The detection, investigation and management of hypertension in pregnancy: executive summary. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2000;40:133–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. The Royal Australian College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG). C-Obs 7 Diagnosis of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Melbourne, Australia: RANZCOG See http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/publications/statements/C-obs7.pdf (udated June 2008; last checked 30 May 2011)

- 18. McCowan L, Horgan RP. Risk factors for small for gestational age infants. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2009;23:779–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mongelli M, Figueras F, Francis A, Gardosi J. A customised birthweight centile calculator developed for an Australian population. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2007;47:128–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sibai BM, Ross MG. Hypertension in gestational diabetes mellitus: pathophysiology and long-term consequences. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2010;23:229–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bakker R, Steegers EAP, Biharie AA, Mackenbach JP, Hofman A, Jaddoe VWV. Explaining the differences in birth outcomes in relation to maternal age: the generation R study. BJOG 2011;118:500–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vardavas CI, Chatzi L, Patelarou E, et al. Smoking and smoking cessation during early pregnancy and its effect on adverse pregnancy outcomes and fetal growth. Eur J Pediatr 2010;169:741–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington E. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:335–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006 Census MapStats. Australian Capital Territory, Australia: ABS. See http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au (updated 15 June 2011; last checked 15 June 2011)

- 25. NSW Department of Health. Communicating Positively – A Guide to Appropriate Aboriginal Terminology. New South Wales, Australia: Centre for Aboriginal Health. See http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/pubs/2004/pdf/aboriginal_terms.pdf (updated 27 May 2004; last checked 15 June 2011)