Abstract

A case of lymphangioleiomyomatosis presenting as multiple pneumothoraces during pregnancy is described below. Presentations, management and prognosis are discussed.

Keywords: pneumothorax, pregnancy, lymphangioleiomyomatosis

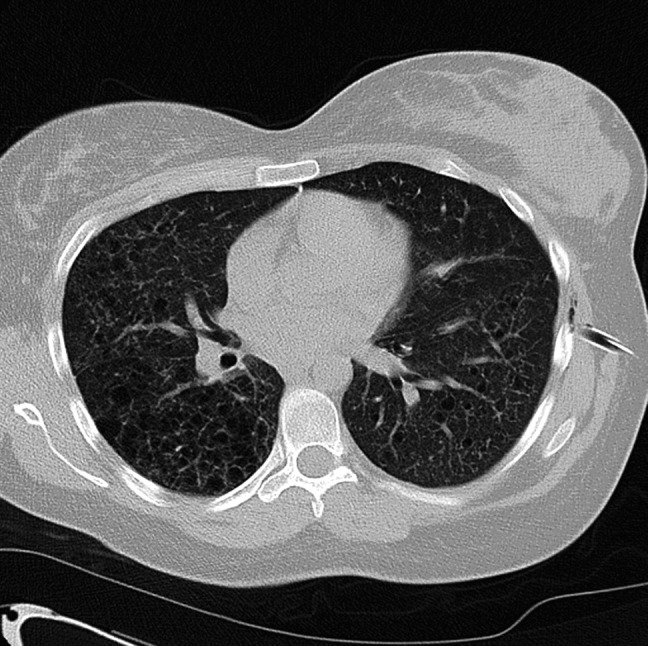

A 30-year-old woman who was 19 weeks pregnant presented to Accident and Emergency with a spontaneous right-sided pneumothorax. The patient had no past medical history and was para 1 + 0, having had an emergency caesarean section for failure to progress 10 years earlier. She had smoked 20 cigarettes per day prior to her pregnancy, but had managed to reduce this to three per day. She had taken Microgynon (combined oral contraceptive pill) for 3–4 months in 2004, but had not been on any contraception since. On admission, her right–sided pneumothorax was successfully aspirated and she was discharged. At this time, the chest radiograph showed a diffuse infiltrative reticulocystic appearance throughout both lungs. Follow-up was arranged for the respiratory clinic. Four days later, this pneumothorax recurred. She was clinically stable on admission with an oxygen saturation of 92% breathing air. The trachea was central, with reduced air entry on the right side. A 50% pneumothorax on the right side was successfully aspirated. Due to family pressures she was discharged with follow-up planned again at outpatients. Shortly after discharge, she was readmitted, and a left pneumothorax was aspirated. Later that evening the patient became increasingly dyspnoeic and again complained of left-sided pleuritic chest pain. Observations remained stable, but chest X-ray (CXR) revealed that the pneumothorax had recurred. Due to the concern of the new contralateral pneumothorax, an intercostal chest drain (ICD) was inserted. A high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) chest was performed. This showed multiple thin-walled cysts in both lungs, predominantly involving the upper lobes and superior basal segments of the lower lobes. Cysts were noted in the right middle lobe and lingula. There was no evidence of significant mediastinal lymphadenopathy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Features were in keeping with lymphangioleiomyomatosis

The patient was transferred to a tertiary centre with obstetric, respiratory medicine and surgery onsite. The aim was for an elective caesarean section after 34 weeks. After transfer, a further right pneumothorax developed for which ICD was refused and was therefore aspirated. Following this, bilateral pneumothoraces developed with marked surgical emphysema (air within subcutaneous tissues) requiring drains.

By this time the patient was becoming increasingly distressed because of multiple CXRs and ICDs. Women who have had a previous section and have a trial of delivery in subsequent labour have increased risks of complication, such as uterine rupture. At this hospital, women at term who have had a previous caesarean sections have a 20% chance of vaginal delivery in subsequent labour (Dr Alan Mathers, personal communication, 7 January 2009). This patient had a previous caesarean section, was 34 weeks gestation and was clinically compromised. It was therefore decided to deliver this baby by emergency caesarean section; a healthy baby boy was delivered. Thoracic surgery, intervened with video-assisted thoracoscopy for lung biopsy, followed by talc pleurodesis on the left side five days later (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Wedge biopsy of lung showing numerous cystic spaces with a thickened alveolar wall

After this procedure, she complained of severe left-sided chest pain associated with reduced oxygen saturations. She required an intercostal block in intensive care, after which she improved.

The following week she developed a tension pneumothorax on the right side initially treated by venflon insertion. The patient improved immediately, with oxygen saturation increasing to 97% and a decreased respiratory rate. A second ICD was then inserted on the right side. A talc pleurodesis of the right side was performed with two ICDs in situ. She was discharged home five months after the initial pneumothorax, having had 10 diagnosed pneumothoraces, six intercostal drains and several aspirations.

She is being followed up at Respiratory Clinic, and her most recent lung function tests show an FEV1 of 1.65 (65% predicted) with normal FEV1/FVC ratio. Vital capacity is reduced with normal gas transfer factor.

COMMENTS

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare disease characterized by smooth muscle proliferation and infiltration leading to cystic destruction of the lung and loss of pulmonary function. It affects around 1300 patients worldwide,1 occurring almost exclusively in premenopausal women. It appears to be exacerbated by pregnancy, although this relationship is uncertain. There are two forms of LAM: sporadic; and that which occurs within a setting of tuberous sclerosis. It has been shown that the prevalence of LAM in TSC is 34%.2

There is evidence that both LAM and tuberous sclerosis share a common genetic origin, both caused by mutations in either of the tuberous sclerosis genes, TSC1 or TSC2. These genes encode the proteins hamartin and tuberin, which act via the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway, controlling cell growth and proliferation. Disruption of the encoded proteins hamartin or tuberin consequently leads to abnormal cellular proliferation.3,4 Although the relationship between pregnancy and LAM has not been fully defined, it is thought that oestrogen can signal through this pathway, causing abnormal cellular proliferation.

The average age at diagnosis of LAM is 35 years.1 Patients have generally had their symptoms for 3–5 years prior to diagnosis, experiencing an average of two pneumothoraces before the diagnosis is made.5 The most common presentations include pneumothorax, dyspnoea and cough.6 HRCT scanning reveals diffuse thin-walled cysts, which allows diagnosis, along with either positive tissue biopsy or the diagnosis occurring in an appropriate clinical context, such as known tuberous sclerosis.

Patients show a progressive decline in lung function. Ten years after the onset of symptoms, half of patients will have dyspnoea walking along flat ground and there is a mortality of 10–20%.7

Management was previously based around hormonal manipulation, such as intramuscular progesterone injections; however, this does not slow the rate of decline of FEV.8 Patients had previously undergone oopherectomy in an attempt to manage the disease; this showed no benefit and is now rarely recommended.9 In all, 60–70% of patients will experience pneumothoraces, resulting in pleurodesis.10 Following this, many patients may ultimately require lung transplantation, which has a 65% survival at five years in the USA.11

Future possibilities for non-surgical management include studies of the genetic pathway controlled by TSC genes 1 and 2. This includes mTOR inhibitors and tyrosine kinase inhibitors to control aberrant cell proliferation. VEGF-D is also being studied due to its role in lymphangiogenesis, as levels of VEGF-D are three times higher in the serum of patients with LAM.12

The relationship between LAM and pregnancy is not fully understood. A study of 69 patients showed that the first pulmonary symptoms occurred during pregnancy in 23%, with two patients developing marked exacerbations.13 Another of 50 patients demonstrated that five had complications, one developed a chylous pleural effusion, three had one or more pneumothoraces during pregnancy and three required lung surgery during pregnancy. It demonstrated that the overall incidence of complications was 11 times higher than at other times.14

Women with LAM should be advised that there is thought to be an increased risk of exacerbations of LAM and pneumothorax in pregnancy. Each patient should be counselled on an individual basis regarding any future pregnancies, based on their current lung function, and any exacerbations in previous pregnancies. The role of oral contraception in LAM remains controversial and at present a causal role has not been found. However, most women are recommended to have an intrauterine device rather than oral contraception.13

LAM is a rare and devastating disease, as illustrated by this patient. With the continuous study of the patients affected, and the molecular pathways involved, there is greater understanding of the disease, which will hopefully lead to the development of further treatment possibilities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks are expressed to Dr Frank McCormack, University of Cincinnati for helpful management discussions. Dr McCormack is Scientific Director of the LAM Foundation in North America.

REFERENCES

- 1. McCormack F. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: A clinical update. Chest 2008;133:507–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moss J, Avila NA, Barnes PM, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of lymphangioleiomyomatosis in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:669–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chorianopoulos D, Stratakos G. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis and tuberous sclerosis complex. Lung 2008;186:197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Curatolo P, Bombardieri R, Jozwiak S. Tuberous sclerosis. Lancet 2008;372:657–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Almoosa KF, Ryu JH, Mendez J, et al. Management of pneumothorax in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: effects on recurrence and lung transplantation complications. Chest 2006;129:1274–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelly J, Moss J. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Med Sci 2001;321:17–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnson SR, Whale CI, Hubbard RB, et al. Survival and disease progression in UK patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Thorax 2004;59:800–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taveira-Dasilva AM, Stylianou MP, Hedin CJ, et al. Decline in lung function in patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis treated with or without progesterone. Chest 2004;126:1867–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Taylor JR, Ryu J, Colby TV, et al. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: clinical course in 32 patients. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1254–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Almoosa KF, McCormack FX, Sahn SA. Pleural disease in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Clin Chest Med 2006;27:355–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kpodonu J, Massad MG, Chaer RA, et al. The US experience with lung transplantation for pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. J Heart Lng Transplant 2005;24:1247–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seyama K, Kumusaka T, Souma S, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-D is increased in serum of patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Lymphat Res Biol 2006;4:143–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Urban T, LAzor R, Lacronique J, et al. pulmonary lymphanioleiomyomatosis: a study of 69 patients; Groupe d'Etudes et de Recherche sur les Maladies “Orphelines” Pulmonaires (GERM “O”P). Medicine (Baltimore) 1999;78:321–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson T. Clinical experience of lymphangioleiomyomatosis in the UK. Thorax 2000;55:1052–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]