Abstract

This study aimed to assess the difference in blood pressure readings between the standard and large cuff and to determine if such a difference applies over a range of arm circumferences (ACs) in pregnancy. We measured blood pressure on 219 antenatal women. Six blood pressure readings were taken, three with a standard ‘adult’ and three with a ‘large’ cuff, in random order. A random zero sphygmomanometer was used by a trained observer. Women with an AC >33 cm were similar in age, gestational age and parity but were heavier and had more hypertension than those with AC ≤33 cm. There was a systematic difference between the standard and large cuff of 5–7 mmHg with little effect due to AC. We were unable to demonstrate an association between the standard and large cuff blood pressure difference and increasing blood pressure. Our study has shown that both systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements are more dependent on the cuff size used than AC and for the individual it is difficult to predict the magnitude of effect the different cuff sizes will have on blood pressure measurements. This study has shown the presence of an average difference in blood pressure measurement between standard and large cuffs in pregnancy, and does not support the arbitrary 33 cm ‘cut-off’ recommended in guidelines for the use of a large cuff in pregnancy.

Keywords: blood pressure measurement, pregnancy, cuff size, arm circumference

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is the most common medical disorder in pregnancy, affecting 10–12% of all pregnancies.1 It is associated with significant maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. The diagnosis of hypertension in pregnancy requires a systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg over several readings. Complications of hypertension in pregnancy still account for an estimated 50,000 maternal deaths annually worldwide.2 It is therefore imperative that blood pressure measurement be accurate.

The Australasian Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy has published a consensus statement for the management of hypertension in pregnancy, including recommendations on blood pressure measurement.3 It is recommended that the patient be seated, with feet supported, for 2–3 minutes before blood pressure is measured. Blood pressure should be taken on both arms at the first antenatal visit. The right arm should be used thereafter if there is no significant difference between the arms. When measuring blood pressure, SBP should be palpated at the brachial artery before inflating the cuff to 20 mmHg above the recorded level. The cuff should then be deflated slowly. DBP is recorded as Korotkoff phase V (K5) and if K5 is not present, can be recorded as Korotkoff phase IV (K4). A standard cuff should be used for arms with a circumference of ≤33 cm while the large cuff (15 × 33 cm bladder) should be used for arms with a circumference of >33 cm. The mercury sphygmomanometer remains the ‘gold standard’ for blood pressure measurement in pregnancy.

Some aspects of these guidelines are well supported by evidence. For example, the use of K5 has been found to be closer to the true intra-arterial diastolic pressure than K4.4 In comparison to K5, K4 has also been shown to be more difficult to detect, with a poorer reproducibility and a greater observer error.5–8 Measurement of blood pressure in the sitting position or left lateral recumbency (on the left arm) rather than the supine position is also evidenced based.9,10

Other aspects of blood pressure measurement in pregnancy remain in question. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring has not yet been recommended for use in routine clinical practice.11–13 Similarly, the use of automated devices for clinical management in pregnant women is not yet recommended.11

The use of a large cuff on a large arm is recommended in both non-pregnant and pregnant individuals.14 However, in the non-pregnant population, there is no evidence-based consensus on the appropriate arm size on which a large cuff should be used. Despite the recommendations in national and international guidelines, there have been no studies to date directly comparing blood pressure measured by the standard and large cuffs in pregnancy.3

AIMS AND HYPOTHESIS

The aims of this study were (1) to assess the difference in blood pressure readings obtained using the standard and large blood pressure cuffs, (2) to determine if such a difference applies over a range of arm circumferences (ACs) in pregnancy, and (3) to determine the AC at which the use of a large cuff is indicated. We hypothesized on the basis of the above recommendations that the standard cuff in pregnant women with an AC >33 cm would result in the overestimation of blood pressure compared with that obtained with a large cuff, and that this overestimation would be greater than that found in women with an AC ≤33 cm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

At the St George Hospital, 220 antenatal women of gestational ages 6–42 weeks were recruited between August 2006 and January 2007 through antenatal clinics, day assessment units, high-risk clinics and obstetric wards. Approximately 2600 deliveries are managed at this unit annually. This study was approved by the South Eastern Sydney and Illawarra Area Health Service Human Research Committee (05/39 Mangos) and the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval no: 06182).

Procedure

Women were approached by the researcher at random. Verbal consent was obtained before the woman was asked to read the information statement, which explained the study in detail. Written consent was then obtained from the patient. The mid-AC (midpoint between the acromion and olecranon) was firstly measured using a tape measure to the nearest 0.5 cm. Blood pressure was measured with the woman comfortably seated, on the right arm, with the lower end of the cuff 2.5 cm above the antecubital fossa. The SBP was initially determined by palpation and then by auscultation using a Hawksley random zero sphygmomanometer. The Korotkoff sounds were auscultated with the cuff deflated by approximately 2 mmHg per second. SBP was recorded as K1. The DBP was recorded as the K5 sound. The average blood pressure from each patient was obtained from three consecutive readings at 2–3-minute intervals using the standard and the large cuffs. Each woman had six blood pressure measurements. The order of cuff size used first was assigned randomly using sealed opaque envelopes, which had been prepared prior to the commencement of the study. Hence, 110 women had three blood pressure measurements taken with a standard cuff first, followed by three measurements with a large cuff. The other 110 women had their blood pressure measured in the reverse order. Patient information regarding current and previous pregnancy was also recorded.

Equipment

Blood pressure was measured by the first author of this study who has completed the British Hypertension Society Blood Pressure Measurement tutorial regarding accurate blood pressure measurement. A quality stethoscope (Littman Cardiology III) with clean, well-fitted earpieces was used. The Hawksley random zero sphygmomanometer (Hawksley and Sons Ltd, Sussex, UK) was used to exclude number preference and was calibrated and serviced prior to commencement of the study. The two cuffs used in this study were the standard (12 × 23 cm) and large (16 × 34 cm) cuffs. A measuring tape was used to measure the patient's AC.

Statistical analysis

The difference between standard and large cuff measurement (standard minus large) is referred to as ΔBP. We used the Lillifor's test to determine whether the clinical characteristics for the subjects were normally distributed. Student's t-test was used for data that were normally distributed continuous variables while the chi-squared test was used for categorised data. For analysing the relationship between ΔBP across the range of ACs, a regression analysis of the scatterplot was used. The agreement between readings with the standard and large cuff was assessed using methods described by Bland and Altman.15,16 Variations of standard compared with large cuff measurements were expressed as 95% confidence intervals. Data analyses were performed using Systat v.10 and Microsoft Excel.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

We recruited 220 pregnant women in this study. One was excluded because of technical difficulties in blood pressure measurement (inability to auscultate Korotkoff sounds, AC = 38.5 cm).

The characteristics of the 219 subjects used in the data analysis are presented in Table 1. Women with AC >33 cm were similar in age, gestational age and parity but were heavier and had more hypertension than those with AC ≤33 cm.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of subjects with normal (AC ≤33 cm) and large (AC >33 cm) arms

| Variable | AC ≤33 cm | AC >33 cm | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects (n) | 179 | 40 | – |

| Average age (years) | 31 (5) | 31 (5) | NS |

| Weight (kg) | 74.6 (14) | 105.1 (13) | <0.001 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 32 (7) | 32 (7) | NS |

| Parity (%) | |||

| Nulliparous | 48 | 32 | NS |

| Multiparous | 52 | 68 | NS |

| Average blood pressure | |||

| Systolic blood pressure | 111 (14) | 121 (14) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 67 (12) | 74 (13) | <0.001 |

| Normotension (%) | 77 | 55 | <0.005 |

| Hypertension (incl. preeclampsia) (%) | 23 | 45 | <0.005 |

Values in parentheses indicate SD

NS = non-significance

Blood pressure

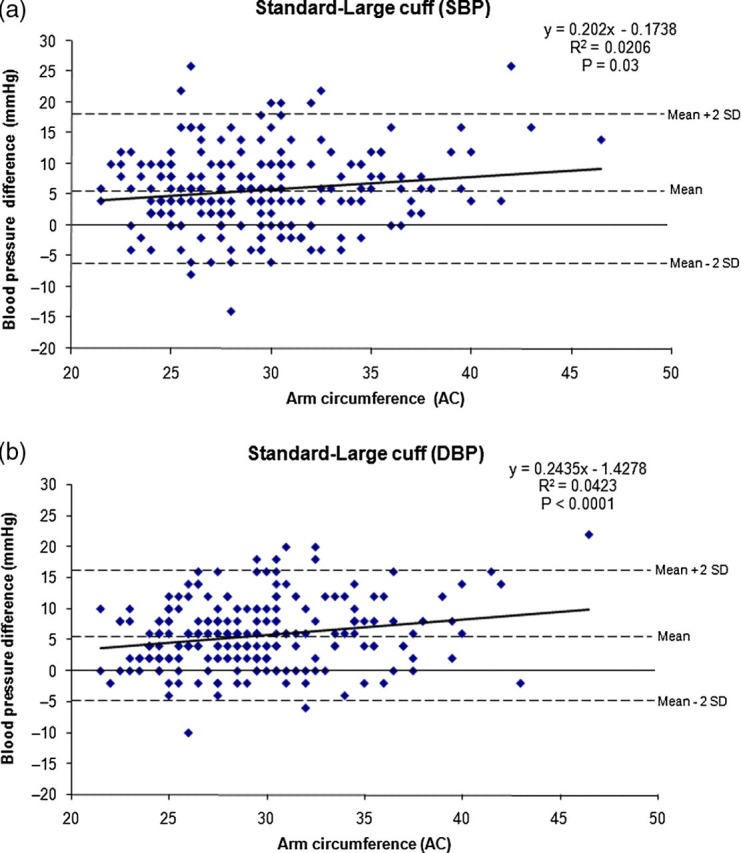

Figure 1(a) and (b) show ΔBP between the standard and large cuff measurements for SBP and DBP, respectively. These graphs show a statistically significant but clinically weak relationship between AC and ΔBP for both SBP and DBP. Although ΔBP increases as AC increases, only 2–4% of the increment can be accounted for by AC. The mean ΔBP (SD) for SBP and DBP was 6 ± 6 and 6 ± 5 mmHg, respectively.

Figure 1.

(a) Scatterplot of ΔSBP readings. SBP = systolic blood pressure (b) Scatterplot of ΔDBP readings. DBP = diastolic blood pressure

The proportion of blood pressure measurements wherein ΔBP readings were positive or negative are shown in Table 2 for both SBP and DBP. In 87% of the women, SBP readings obtained with the standard cuff were equal to or higher than that of the large cuff. Similarly, 92% of DBP readings with the standard cuff were equal to or higher than that of the large cuff.

Table 2.

Proportion of blood pressure measurements where ΔBP is above or below zero

| ΔBP ≥0 | ΔBP <0 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | 190/219 = 87% | 29/219 = 13% | <0.05 |

| DBP | 201/219 = 92% | 18/219 = 8% | <0.05 |

SBP = systolic blood pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure

Table 3 shows the percentage of readings falling into the hypertensive range in subjects with small (AC ≤33 cm) and large (AC >33 cm) arms when measured by the standard or large cuff in this study. Compared with a large cuff, a standard cuff will diagnose hypertension in an extra 5% of women with AC ≤33 cm and an extra 7% of women with AC >33 cm. Hypertension was diagnosed more often with a standard cuff but also more often in women with AC >33 cm regardless of the cuff size.

Table 3.

Diagnosis of hypertension (SBP ≥140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥90 mmHg) according to cuff size

| Overall hypertensive (%) | AC ≤33 cm | AC >33 cm | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard cuff | 24 (11) | 14/179 = 8% | 10/40 = 25% | <0.05 |

| Large cuff | 12 (5) | 5/179 = 3% | 7/40 = 18% | <0.05 |

SBP = systolic blood pressure; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; AC = arm circumference

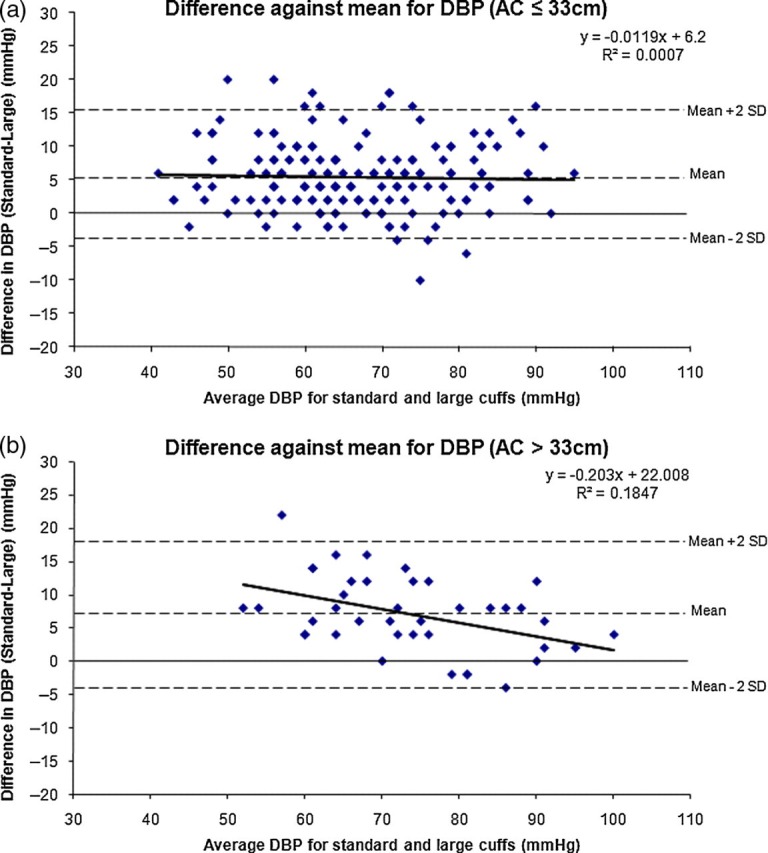

Figures 2 and 3 show the Bland–Altman plots of ΔSBP and ΔDBP readings in subjects with AC ≤33 cm, and in those with AC >33 cm. These plots show that there is no relationship between the difference in blood pressure obtained by the standard and large cuff with increasing blood pressure. The discrepancy between readings obtained with a standard and large cuff was consistent across a blood pressure range in most pregnant women. This difference was weakly related to AC but not related to the blood pressure itself. The sole exception to this finding is seen in Figure 3(b), which shows that as average DBP rises, the discrepancy in readings between standard and large cuffs becomes less.

Figure 2.

(a) Bland–Altman plot of SBP readings in subjects with AC ≤33 cm. Mean difference ± SD in SBP between methods of measurement in subjects with AC <33 cm is 5 ± 6 mmHg. (b) Bland–Altman plot of SBP readings in subjects with AC >33 cm. Mean difference ± SD in SBP between methods of measurement in subjects with AC >33 cm is 7 ± 6 mmHg. SBP = systolic blood pressure; AC = arm circumference

Figure 3.

(a) Bland–Altman plot of DBP readings in subjects with AC ≤33 cm. Mean difference ± SD in DBP between methods of measurement in subjects with AC <33 cm is 5 ± 5 mmHg. (b) Bland–Altman plot of DBP readings in subjects with AC >33 cm. Mean difference ± SD in DBP between methods of measurement in subjects with AC >33 cm is 7 ± 6 mmHg. DBP = diastolic blood pressure; AC = arm circumference

The mean difference in blood pressure obtained using the standard and large cuff for AC ≤33 cm was 5 ± 6/5 ± 5 mmHg and that for AC >33 cm was 7 ± 6/7 ± 6 mmHg (not significant). In other words, there was a mean difference of only 2 mmHg between the blood pressure differences obtained in women with small and large arms, a difference well within the error of measurement of blood pressure.

There was no statistically significant difference in the number of blood pressure readings that ended in 0, 2, 4, 6 or 8.

DISCUSSION

Accurate blood pressure measurement is of paramount importance in the management of hypertension in pregnancy. Contrary to popular belief and most international recommendations, our study has shown that SBP and DBP readings are probably more dependent on the cuff size used than on which cuff is chosen for which AC, i.e. a larger cuff will lead to a lower blood pressure reading of about −5 mmHg overall, whereas a larger arm will only lead to a +2 mmHg difference overall.

Although the difference between the standard and large cuff increased as AC increased, there was no discrete cut-off point at which this occurred (see Figure 1) and the relationship was very weak. Therefore, this study does not support a particular AC at which a large cuff should be used. There appears to be a consistent overestimation on average of between 5 and 7 mmHg, enough to affect the diagnosis of hypertension. These data show that 5–7% of women would not qualify for a diagnosis of hypertension using the large cuff on the day of their participation. From the Bland–Altman plots, we also found that there is a mean systematic difference between the standard and large cuff of approximately 5 mmHg regardless of the AC for both SBP and DBP. This error is minimally affected by rising blood pressure, although we have not yet studied women with more severe hypertension. It is important to note from the Bland–Altman plots that for individuals it is difficult to predict what effect the different cuff sizes will have on blood pressure measurements, regardless of AC.

Similar results have been reported in the non-pregnant population. Croft and Cruickshank found that the means of standard cuff measurements were higher than that of the large cuff for both SBP and DBP. They also found that ΔBP increased with AC but this increment was not significant over the range of ACs.17 Likewise, Simpson and colleagues found that using wider and longer bladders in comparison to narrower and shorter ones resulted in lower blood pressure readings. Nevertheless, this difference was not affected by the size of the arm.14

Bakx and colleagues found that there is an increase in SBP and DBP with increasing AC but blood pressure differences between the different cuff sizes were not significant. Their study included 130 male and female subjects, 39% of whom had AC >35 cm. The design of their study was similar to ours. The authors found a mean differences of only 2.1 mmHg systolic and 1.6 mmHg diastolic when they compared blood pressure readings obtained from cuffs of 23 cm and 36 cm in length, less than the 5–7 mmHg difference we found in pregnant women. They concluded that cuff size is of minor importance in blood pressure measurement in comparison with other factors.18

Other studies have also demonstrated a relatively small effect of cuff size on blood pressure measurement, in particular when using the large cuff on a small arm. One study comparing intra-arterial blood pressure with auscultatory measurements found that long bladdered cuffs did not underestimate intra-arterial pressure in subjects with normal sized arms.19 Similarly, Croft and Cruickshank found that there was no overall difference between DBP measurements using the standard (12 × 23 cm) and large (15 × 33 cm) cuffs in patients with AC ≤30 cm. The dimensions of the standard and large cuffs used in that study were similar to those used in the present study.17 Consistent with the findings of these studies, Linfors et al. 20 found that blood pressure was independent of the cuff size in subjects with an AC < 35 cm.

Blood pressure in our study was carefully measured by a trained observer using a random zero sphygmomanometer. Our findings show that in most, but not all, cases there was a systematic error between the standard and large cuff for both SBP and DBP.

Despite the ongoing debate concerning the importance of cuff size in blood pressure measurement, there has been a longstanding consensus that a short and narrow cuff results in the overestimation of blood pressure whereas a long and wide cuff results in the underestimation of blood pressure.21–24 The use of a different equipment (blood pressure measuring device, cuff size and type), position of subject, Korotkoff sound used in determining DBP as well as the possibility of the occurrence of white coat hypertension has made it difficult to compare the studies. We have attempted to reduce the ‘white-coat effect’ by performing multiple measurements and using the mean of three readings. Digit preference and observer bias was excluded as best as possible in our study by the use of a random zero sphygmomanometer.

One study on 196 primigravidas showed that failure to use an appropriate cuff size overestimated the diagnosis of pregnancy-induced hypertension fourfold.25 This trend, though not the extent, is consistent with our results wherein using a standard cuff in women with large arms resulted in the diagnosis of hypertension in 25% in comparison to 18% with the large cuff. Similarly, hypertension was underdiagnosed by 5% when a large instead of a standard cuff was used in subjects with small arms. The clinical significance of these effects are unknown, as our study was cross sectional and a longitudinal study examining pregnancy outcomes would be required to answer this question.

LIMITATIONS

There are some limitations of this study. First, the accuracy of the Hawksley random zero sphygmomanometer has been questioned as it has been found that its use resulted in the underestimation of both SBP and DBP when the readings were compared with those obtained with the standard mercury sphygmomanometer.26,27 Nevertheless, the use of the Hawksley random zero sphygmomanometer is substantiated in this study as the difference in blood pressure readings in relation to cuff sizes was tested, as opposed to the exact reading itself. It has been shown that the random zero sphygmomanometer does not have adverse effects on the results obtained from studies which aim to improve protocols for blood pressure measurement.28

We have assumed in this study that there is no significant discrepancy between direct (intra-arterial) and indirect (mercury sphygmomanometry) blood pressures. A study by Brown et al. 4 on pregnant women showed that auscultatory sphygmomanometry underestimated SBP by 11 mmHg and overestimated DBP, defined as K5, by 4 mmHg. Although there may be significant differences in readings obtained from direct and indirect measurements, it is not appropriate to routinely measure blood pressures using the intra-arterial method, and this is not clinically relevant.

Further limitations of this study are the smaller number of subjects with an AC >33 cm or severe hypertension. However, our results suggest that it is unlikely that larger numbers of subjects would allow us to determine a single ‘cut-off’ AC to be defined for the use of a large cuff.

Further study is needed in deciding whether cuff size plays an important role in the measurement of blood pressure in pregnancy. Comparing readings obtained with intra-arterial and auscultatory methods when using the standard and large cuffs would be the only way to identify the accuracy of cuff size in blood pressure measurement in pregnancy. However, even this study may prove of limited use if there is a continued move away from mercury sphygmomanometry and perhaps a study comparing cuff size using automated blood pressures with intra-arterial readings will one day be necessary.

CONCLUSION

This study has shown the presence of an average difference in blood pressure measurement between standard and large cuffs in pregnancy, and does not support the 33 cm ‘cut-off’ recommended in guidelines for the use of a large cuff in pregnancy. Whether all pregnant women should have blood pressure measured by a standard cuff (in order to optimize sensitivity of diagnosis of hypertension) or a large cuff (which will lead to underestimation of the incidence of hypertension in pregnancy) requires further study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brown MA, Davis GK. Treatment in special conditions In: Mancia G, Chalmers J, Julius S, Saruta T, Weber MA, Ferrari AU, et al. , eds Hypertension in Pregnancy. London: Harcourt Publishers Limited, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Duley L. Maternal mortality associated with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. BJOG: An Int J Obstet Gynaecol 1992;99:547–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown M, Lindheimer M, de Swiet M, Van Assche A, Moutquin J. The classification and diagnosis of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: statement from the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP). Hypertens Pregnancy 2001;20:x–xiv [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown MA, Reiter L, Smith B, Buddle ML, Morris R, Whitworth JA. Measuring blood pressure in pregnant women: a comparison of direct and indirect methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;171:661–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walker SP, Higgins JR, Brennecke SP. The diastolic debate: is it time to discard Korotkoff phase IV in favour of phase V for blood pressure measurements in pregnancy? Med J Aust 1998;169:203–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Duggan PM. Which Korotkoff sound should be used for the diastolic blood pressure in pregnancy? Aust N Z J Obst Gynaecol 1998;38:194–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shennan A, Gupta M, Halligan A, Taylor DJ, de Swiet M. Lack of reproducibility in pregnancy of Korotkoff phase IV as measured by mercury sphygmomanometry. Lancet 1996;347:139–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rubin P. Measuring diastolic blood pressure in pregnancy: use the fifth Korotkoff sound. British Medical Journal 1996;313:4–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kinsella SM. Effect of blood pressure instrument and cuff side on blood pressure reading in pregnant women in the lateral recumbent position. Int 2006;15:290–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kinsella SM, Spencer JAD. Blood pressure measurement in the lateral position. British J Obstet Gynaecol 1989;96:1110–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown MA, Hague WM, Higgins J, et al. The detection, investigation and management of hypertension in pregnancy: executive summary: full consensus statement. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2000;40:139–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bergel E, Carroli G, Althabe F. Ambulatory versus conventional methods for monitoring blood pressure during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 2. Art No.: CD001231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walker SP, Higgins JR, Brennecke SP. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1998;53:636–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simpson JA, Jamieson G, Dickhaus DW, Grover RF. Effect of size of cuff bladder on accuracy of measurement of indirect blood pressure. Am Heart J 1965;70:208–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986;1:307–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bland JM, Altman DG. Comparing methods of measurement: why plotting difference against standard method is misleading. Lancet 1995;346:1085–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Croft PR, Cruickshank JK. Blood pressure measurement in adults: large cuffs for all? J Epidemiol Community Health 1990;44:170–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bakx C, Oerlemans G, vandenHoogen H, vanWeel C, Thien T. The influence of cuff size on blood pressure measurement. J Hum Hypertens 1997;11:439–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Montfrans GA, van der Hoeven GM, Karemaker JM, Wieling W, Dunning AJ. Accuracy of auscultatory blood pressure measurement with a long cuff. Br Med J 1987;295:354–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Linfors EW, Feussner JR, Blessing CL, Starmer CF, Neelon FA, McKee PA. Spurious hypertension in the obese patient. Effect of sphygmomanometer cuff size on prevalence of hypertension. Arch Intern Med 1984;144:1482–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nielsen PE, Janniche H. The accuracy of auscultatory measurement of arm blood pressure in very obese subjects. Acta Med Scand 1974;195:403–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Irvine ROH. The influence of arm girth and cuff size on the measurement of blood pressure. N Z Med J 1968;67:279–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Geddes LA, Whistler SJ. The error in indirect blood pressure measurement with the incorrect size of cuff. Am Heart J 1978;96:4–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wittenberg C, Erman A, Sulkes J, Abramson E, Boner G. Which cuff size is preferable for blood pressure monitoring in most hypertensive patients? J Hum Hypertens 1994;8:819–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schoenfeld A, Ziv I, Tzeel A, Ovadia J. Roll-over test–errors in interpretation, due to inaccurate blood pressure measurements. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1985;19:23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. O'Brien E, Mee F, Atkins N, O'Malley K. Inaccuracy of the Hawksley random zero sphygmomanometer. Lancet 1990;336:1465–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Parker D, Liu K, Dyer AR, Giumetti D, Liao YL, Stamler J. A comparison of the random-zero and standard mercury sphygmomanometers. Hypertension 1988;11:269–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Conroy RM, O'Brien E, O'Malley K, Atkins N. Measurement error in the Hawksley random zero sphygmomanometer: what damage has been done and what can we learn? Br Med J 1993;306:1319–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]