Abstract

Background and Aims:

Pre-operative investigations are often required to supplement information for risk stratification and assessing reserve for undergoing surgery. Although there are evidence-based recommendations for which investigations should be done, clinical practice varies. The present study aimed to assess the pre-operative investigations and referral practices and compare it with the standard guidelines.

Methods:

The present observational study was carried out during 2014–appen2015 in a teaching institute after the approval from Institute Ethical Committee. A designated anaesthesiologist collected data from the completed pre-anaesthetic check-up (PAC) sheets. Investigations already done, asked by anaesthesiologists as well as referral services sought were noted and compared with an adapted master table prepared from standard recommendations and guidelines. Data were expressed in frequencies, percentage and statistically analysed using INSTAT software (GraphPad Prism software Inc., La Zolla, USA).

Results:

Seventy-five out of 352 patients (42.67% male, 57.33% female; American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I to III) were included in this study. Nearly, all patients attended PAC with at least 5 investigations done. Of them, 89.33% were subjected to at least one unnecessary investigation and 91.67% of the referral services were not required which lead to 3.5 ( SD ±1.64) days loss. Anaesthesiologist-ordered testing was more focused than surgeons.

Conclusion:

More than two-third of pre-operative investigations and referral services are unnecessary. Anaesthesiologists are relatively more rational in ordering pre-operative tests yet; a lot can be done to rationalise the practice as well as reducing healthcare cost.

Key words: Elective surgery, pre-anaesthetic check-up, pre-operative investigation, pre-operative referrals, routine investigation

INTRODUCTION

Pre-anaesthetic check-up (PAC) is a basic element in anaesthetic care. It is defined as the process of clinical assessment that precedes the delivery of anaesthesia care for surgical and non-surgical procedures.[1] The PAC needs the consideration of information from multiple sources including pre-operative investigations. ‘Routine investigations’ are quite routine practice though there are negative recommendations and clear note in the guidelines that routine investigations are not needed in all patients.[1,2] There is a relative dearth of data on practice patterns and its comparisons with standard guidelines and recommendations from developing countries. The present study aimed to assess the pre-operative investigations and referral practices and compare it with such guidelines and recommendations. This will help in making decision, protocols, policy, provide cost-effective healthcare and contribute to the economy.

METHODS

After the approval of Institutes’ Ethical Committee, the present prospective observational study was conducted during March 2014 to June 2015. Patients of any American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status of both sexes planned for elective surgery or interventional procedures requiring anaesthetic services were included in this study. All patients attending PAC outpatient department (OPD) for evaluation and risk stratification were included except the patients undergoing cardiac surgeries. The evaluating anaesthesiologist completed PAC and noted and/or advised the investigations which he/she thought as required. The data were collected by a fixed designated anaesthesiologist for the entire duration of the study by screening the investigation files as well as the completed PAC record sheets. However, designated anaesthesiologist did not filter out any investigations. The designated anaesthesiologist (data collector) also did not intervene to modify the PAC process conducted by other colleague of the same rank. However, if the evaluating person was a postgraduate trainee and requested an opinion from the designated anaesthesiologist, advice was given as part of teaching, training and patient care. The patients were thus evaluated, and the patients who were directly evaluated by the designated anaesthesiologist were not included in the study. However, if any anaesthesiologist senior to the designated anaesthesiologist intervened/supervised/advised some investigation/s or referral in the patients who were being evaluated by the designated anaesthesiologist; those patients were also included in the study.

The age, sex, weight, operation planned, ASA physical statuses, comorbid conditions, metabolic equivalent of tasks (METs) were also noted. Surgical procedures/interventional procedures were divided into three categories adapted from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence classification[2] (i.e., minor, intermediate and major) for this study. The investigations already done by surgical team before sending the patient to PAC OPD for evaluation and risk stratification as well as the investigations enquired/noted by anaesthesiologists in the PAC record sheet and referrals sought were noted. However, the investigations done for diagnostic purposes were excluded from this study. The times required for fitness declaration after evaluation by the referee doctors were also noted. A master table [Appendix 1] of investigations recommended based on the type of surgery, age, METs, ASA physical status, comorbidity, etc., were prepared from few standard guidelines and recommendations in this field.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8] The data collected for the present study were evaluated against this master table. Data were expressed in absolute number and percentage scale. Further statistical tests to analysis the data were done by appropriate statistical tests using INSTAT software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Zolla, CA, USA) and P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 352 patients were screened on the OPD days on which the designated anaesthesiologist got random posting in PAC OPD. Out of them, 75 patients were eligible for the study based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

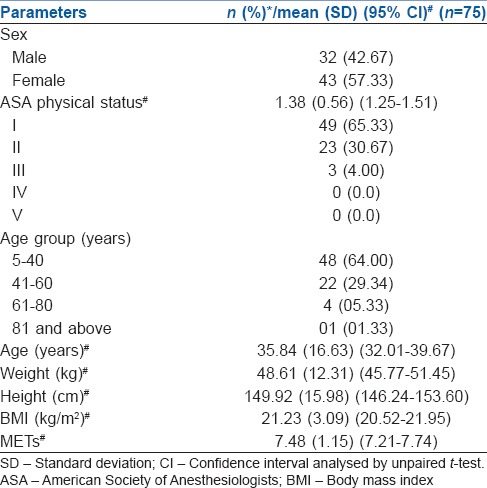

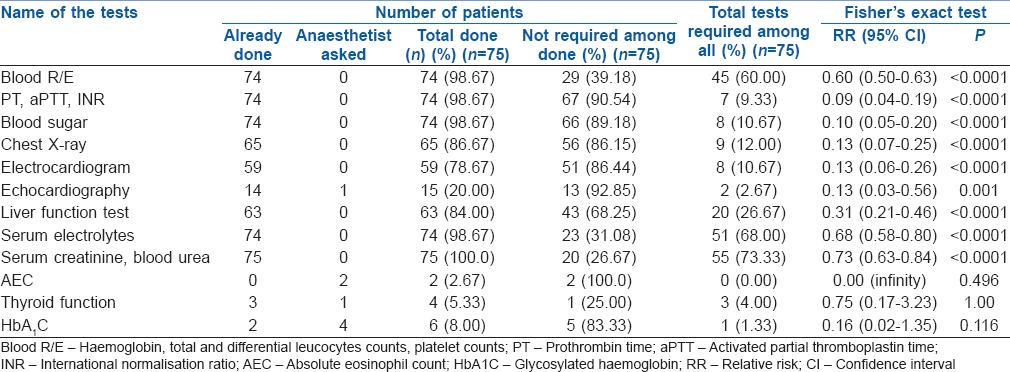

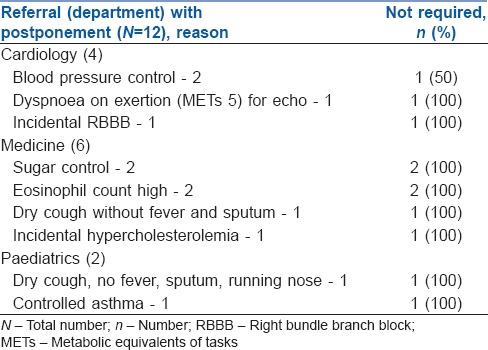

Majority (57.33%) of the patients were female and of ASA physical status I (65.33%). Body mass indices of the patients were between 15.12 and 28.69 kg/m2 with a mean value of 21.236. The demographic parameters and physical status of the studied sample are included in Table 1. Fifty-two (69.33%) patients underwent major surgery. Twenty-four (32%) patients had at least one comorbidity with pallor (anaemia) and hypertension being the most common comprising 8 (10.67%) each. Other common comorbid conditions were diabetes mellitus and smoking, 5 (6.67%) each, renal failure and other renal diseases, 5 (6.67%). There were 1 (1.33%) each of cardiovascular, respiratory and thyroid disorder also and none of the patient was having METs <4. Almost 99% of the patients attended the PAC OPD with blood routine examinations (haemoglobin [Hb], total and differential leucocytes counts, platelet counts), serum electrolytes (sodium, potassium, calcium, chloride), blood sugar, blood urea and serum creatinine levels already done. Out of these, 89.33% patients were subjected to at least one investigation which was not required/recommended [Table 2]. Twelve (16%) patients were referred to other departments, out of which 11 (91.67%) of the referral services were deemed as not required [Table 3].

Table 1.

Frequency table of demographic parameters and comorbidities of the patients

Table 2.

Table of investigations done by surgeons and anaesthetists and their comparison with standards

Table 3.

Frequency table showing the patterns of referral services sought by anaesthesiologists

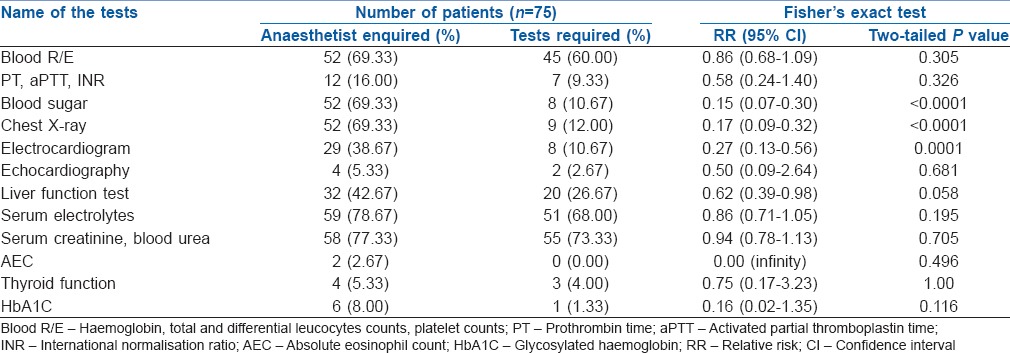

Most of the investigations were already done by surgical colleagues before sending the patient for PAC and risk stratifications. The evaluating anaesthesiologist recognised that many of the investigations done were not necessary, and so, not all investigations were noted in the PAC record sheet. Comparison of these recorded (anaesthesiologist thought as required) investigations revealed that anaesthesiologists were nearly rational (3-9% unnecessary, P > 0.05) in deciding the requirement of pre-operative tests in context to blood cell counts, Hb, coagulation profile, blood urea, serum electrolytes, creatinine and echocardiography (ECHO) [Table 4]. However, among the chest X-rays (CXRs), blood sugar measurements and electrocardiograms (ECGs) that anaesthesiologists thought as necessary and recorded in the PAC sheet, 21-44% of these were still done unnecessarily when compared with recommendations and the difference was highly significant (P = 0.001) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Investigations thought to be required by anaesthesiologist and their comparison with standards

DISCUSSION

Cost-effective healthcare delivery has great relevance to developing countries. One of the major drivers of healthcare costs is the inappropriate utilisation of advanced medical technology and services.[9] Routine pre-operative investigational services appear to be one such area.

The goal of PAC is to gather information about the patient and formulating an anaesthetic plan for conducting smooth anaesthesia without or minimal perioperative morbidity and mortality.[10] Identification of unsuspected conditions requiring treatment before surgery or a change in anaesthetic management may be a possible benefit of routine pre-operative investigations, but a false positive finding may lead to unnecessary, costly and possibly harmful treatments or further investigations leading to delay in surgery.[11] The ASA has stated that ‘no routine laboratory or diagnostic screening test is necessary for the pre-anaesthetic evaluation of patients’.[12] The pre-operative investigations should be based on the history, physical examination, perioperative risk assessment and clinical judgment.[13] In this context, the present finding of at least five investigations already being done in nearly all the patients before attending for PAC is a big concern.

The ‘routine’ screening of full blood count contributes little in patient's management.[14] In this study, routine blood examinations were done in 98.67% patients, and 61.33% of Hb measurements were actually not required. Evidence does not support routine CXR for patients aged below 70 years without risk factors as it does not decrease morbidity or mortality.[15] In the present study, 86.67% of the patients had undergone CXR and out of these more than 85% were unnecessary. The present study also reveals similar findings for ECG, two-dimensional (2D) ECHO and blood sugar measurements. Only one (1.52%) blood sugar level came in impaired range; however, it did not change the anaesthetic management.

One of the reasons provided by perioperative team for doing routine investigations is getting rid of being sued for not detecting subclinical medical problems which may manifest during perioperative period. This reason probably can be discarded as the court of law depends on evidence; and current evidences indicate that the incidental findings or abnormal test results of routine pre-operative tests hardly change anaesthetic management.[16,17] Moreover, a medico-legal problem can even arise when the tests come out to be normal and patient alleges that the tests were done for the monetary benefit. An empathetic approach, effective communication, up to date knowledge, informed consent, good record keeping and sympathy without accepting blame from patients is probably an answer to it and also can reduce the chance of being sued.[18]

Four (5.33%) patients had minor and incidental findings (i.e., increase in eosinophil counts, right bundle branch block, etc.) in the routine testing. This led to unnecessary referrals as well as delay in declaring fitness. Asking for the absolute eosinophil count was a total waste of time as it could have been calculated directly from the already done counts. One thyroid function test was carried out unnecessarily in a patient whose 3 months prior report was found to be normal despite no changes in thyroid-related symptoms and therapy.[19]

The present study shows similar, if not worse, findings as compared to the study done in Srilanka.[20] The mentioned study found very poor compliance to the local recommendations for CXRs, coagulation profiles, liver enzymes and 2D ECHO. Another retrospective review found that 100% of the patients had many routine investigations done, but there was no change in the plan of anaesthesia in any of these cases despite having 32.5% abnormal test results for some of the tests.[21]

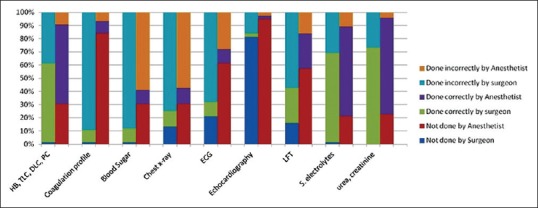

Eleven (91.67%) referrals to other physicians in the present study were also not required. Four patients required change in the management of comorbid conditions, but none of them changed anaesthetic management. Although two cases were cleared on the same day with advice to produce the reports day before surgery, there were a mean 3.5 ± 1.64 days of delay in rest. Other interesting finding is the difference in the pre-operative routine tests order pattern between surgeons and anaesthesiologists. Anaesthesiologists were more rational in deciding the requirement of most of the routine tests (41-97% vs. 10-60%) [Figure 1]. This reconfirms that the anaesthesiologist-ordered testing is more focused and less costly as compared to surgeon.[22]

Figure 1.

100% stacked cluster column graph of the investigations done, not done, required by surgeon and anaesthetist. (Hb: Haemoglobin, TLC: Total leucocytes counts, DLC: Differential leucocytes counts, PC: Platelet counts, (coagulation profile-prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time and international normalisation ratio), ECG: Electrocardiogram, LFT: Liver function test)

The advantage of the present study is the prospective data collection on random OPD days, but this led to a smaller sample. The comparison is done with an adapted table prepared from multiple guidelines mostly based on level II evidence. Therefore, the present study can be taken as pilot study and guide for further studies. Pre-anaesthetic investigative practices differ a lot; so, future similar studies are expected to give different results. However, considering the very high percentage of investigations done unnecessarily with extreme statistical significance, the conclusions drawn from future studies are unlikely to be different.

CONCLUSION

The uses of unnecessary pre-operative tests are very much prevalent despite the growing body of evidence that such investigations do not help. Anaesthesiologists are relatively more rational in ordering pre-operative tests yet; a lot can be done to rationalise the practice as well as to reduce healthcare cost without compromising on the quality of the patient care.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the help of Ms. Aisha Khan from Doha, Qatar for language editing.

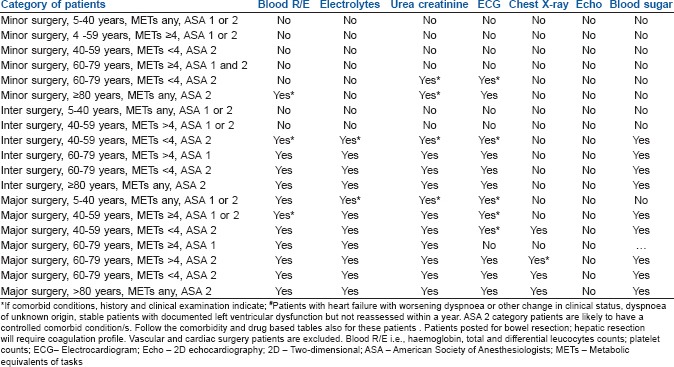

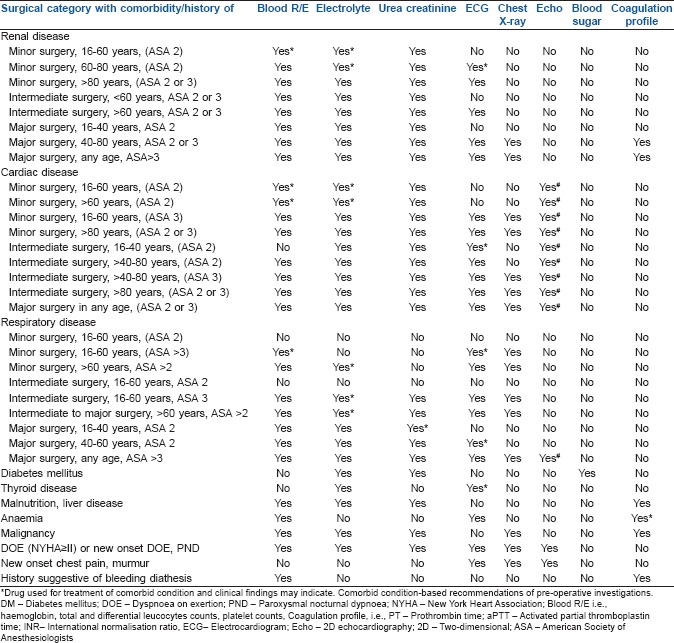

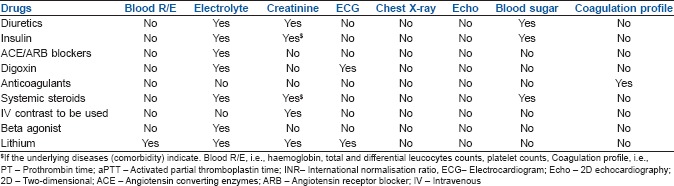

Master table of recommended pre-operative investigations for elective surgeries for age ≥5 years (adapted[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8])

Special Tests

Thyroid function test: History of hypo or hyperthyroidism but status not accessed in last 6 months, change in symptoms, history of thyroidectomy, parathyroidectomy.

Liver function test: All patients posted for cholecystectomy, Known or suspected liver disease, Inflammatory bowel disease, excess alcohol intake and advanced malignancy.

Glycosylated haemoglobin: History of diabetes or suggestive of diabetes and if sugar has not been checked recently, if random blood glucose >11mmoL/L (approximately 200 mg/dL) in patients with a history of steroid intake or body mass index >35.

Other tests such as Pregnancy test, Lung function test, Blood gases, Electroencephalography are not included here.

REFERENCES

- 1.Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters; Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, Pasternak LR, Arens JF, et al. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:522–38. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Preoperative tests: The use of routine preoperative tests for elective surgery – Evidence, methods and guidance. London: National Institute of Clinical Excellence; 2003. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 22]. National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care (UK) Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg3 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, Barnason SA, Beckman JA, Bozkurt B, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:e77–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kristensen SD, Knuuti J, Saraste A, Anker S, Bøtker HE, Hert SD, et al. 2014 ESC/ESA guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: Cardiovascular assessment and management: The joint task force on non-cardiac surgery: Cardiovascular assessment and management of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2383–431. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pre-operative Assessment and Patient Preparation. The Role of the Anaesthetist. London: AAGBI; 2010. [Last cited on 2015 Sep 25]. The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Available from: http://www.aagbi.org/sites/default/files/preop2010.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pre-operative Assessment Guidelines V4.0. Cornwall: Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust. 2014. [Last cited on 2015 Oct 03]. Available from: http://www.rcht.nhs.uk/DocumentsLibrary/RoyalCornwallHospitalsTrust/Clinical/Anaesthetics/PreOperativeAssessmentGuidelines.pdf .

- 7.Sweitzer BJ. Preoperative evaluation and medication. In: Miller RD, Pardo MC Jr, editors. Basics of Anesthesia. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011. pp. 165–88. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinical Practice Guideline v1. Winnipeg, Canada: Winnipeg Regional Health Authority; 2010. [Last cited on 2015 Aug 24]. Routine Preoperative Lab Tests for Adult Patients (age≥16 years) Undergoing Elective Surgery. Available from: http://www.wrha.mb.ca/professionals/familyphysicians/files/GRIDFINALDec.10.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Controlling Health Care Costs While Promoting the Best Possible Health Outcomes. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 2009. [Last cited on 2015 Sep 29]. American College of Physicians. Available from: https://www.acponline.org/acp_policy/policies/controlling_healthcare_costs_2009.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duke JC, Chandler M. Preoperative evaluation. In: Duke JC, Keech BM, editors. Anesthesia Secrets. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2016. p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asua J, López-Argumedo M. Preoperative evaluation in elective surgery. INAHTA synthesis report. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2000;16:673–83. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300101230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statement on routine preoperative laboratory and diagnostic screening. Illinois, USA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; 2003. [Amended on 2008 Oct 22; Last cited on 2015 Nov 19]. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Available from: http://www.asahq.org/~/media/legacy/for%20members/documents/standards%20guidelines%20stmts/routine%20preoperative%20laboratory%20and%20diagnostic%20screening.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feely MA, Collins CS, Daniels PR, Kebede EB, Jatoi A, Mauck KF. Preoperative testing before noncardiac surgery: Guidelines and recommendations. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:414–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munro J, Booth A, Nicholl J. Routine preoperative testing: A systematic review of the evidence. Health Technol Assess. 1997;1:1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joo HS, Wong J, Naik VN, Savoldelli GL. The value of screening preoperative chest x-rays: A systematic review. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:568–74. doi: 10.1007/BF03015764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez A, Planell J, Bacardaz C, Hounie A, Franci J, Brotons C, et al. Value of routine preoperative tests: A multicentre study in four general hospitals. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74:250–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/74.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narr BJ, Hansen TR, Warner MA. Preoperative laboratory screening in healthy Mayo patients: Cost-effective elimination of tests and unchanged outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66:155–9. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60487-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.RD 14 Medico Legal Issues 2011. Melbourne, Australia: Anaesthesia Continuing Education Coordinating Committee, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists; 2011. [Last accessed 2016 Jan 12]. Welfare of Anaesthetists Special Interest Group. Available from: http://www.anzca.edu.au/documents/rd-14-medico-legal-issues-2011 . [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wijeysundera DN, Sweitzer BJ. Preoperative evaluation. In: Miller RD, editor. Miller's Anesthesia. 8th ed. Philadelphia, USA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015. p. 1115. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranasinghe P, Perera YS, Senaratne JA, Abayadeera A. Preoperative testing in elective surgery: Is it really cost effective? Anesth Essays Res. 2011;5:28–32. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.84177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandra A, Thakur V, Bhasin N, Gupta D. The role of pre-operative investigations in relatively healthy general surgical patients – A retrospective study. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2014;18:241–4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finegan BA, Rashiq S, McAlister FA, O’Connor P. Selective ordering of preoperative investigations by anesthesiologists reduces the number and cost of tests. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:575–80. doi: 10.1007/BF03015765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]