Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is frequent in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and has been related to angiotensin II (ANG II), endothelin-1 (ET-1), thromboxane A2 (TxA2) and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Since activation of thromboxane prostanoid receptors (TP-Rs) can generate ROS which can generate ET-1, we tested the hypothesis that CKD induces cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 whose products activate TP-Rs to enhance ET-1 and ROS generation and contractions. Mesenteric resistance arterioles were isolated from C57/BL6, or TP-R +/+ and TP-R −/− mice 3 months after SHAM-operation (SHAM) or surgical reduced renal mass (RRM, n=6/group). Microvascular contractions were studied on a wire myograph. Cellular (ethidium: dihydroethidium) and mitochondrial (mitoSOX) ROS were measured by fluorescence microscopy. Mice with RRM had increased excretion of markers of oxidative stress, thromboxane, and microalbumin, increased plasma ET-1 and increased microvascular expression of p22phox, COX-2, TP-Rs, preproendothelin and endothelin-A receptors and increased arteriolar remodeling. They had increased contractions to U-46,619 (118±3 vs. 87±6, P<0.05) and ET-1 (108±5 vs. 89±4, P<0.05), which were dependent on cellular and mitochondrial ROS, COX-2, and TP-Rs. RRM doubled the ET-1-induced cellular and mitochondrial ROS generation (P<0.05). TP-R −/− mice with RRM lacked these abnormal structural and functional microvascular responses and lacked the increased systemic and the increased microvascular oxidative stress and circulating ET-1. In conclusion, RRM leads to microvascular remodeling and enhanced ET-1-induced cellular and mitochondrial ROS and contractions that are mediated by COX-2 products activating TP-Rs. Thus, TP-Rs can be upstream from enhanced ROS, ET-1, microvascular remodeling and contractility and may thereby coordinate vascular dysfunction in CKD.

Keywords: Vascular remodeling, mitochondria, cyclooxygenase, thromboxane, oxidative stress

Introduction

Although chronic kidney disease (CKD) is progressive, most patients die from cardiovascular disease (CVD) before reaching end stage renal disease (ESRD)1. CVD in patients with CKD is unusual since it is not clearly associated with hypertension, hypercholesterolemia or obesity (unless extreme)2–5. Uncertainty concerning the underlying vascular mechanisms has hampered the development of strategies to prevent the CVD.

Patients with CKD have vascular endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress that can be detected in CKD stage 16, 7. These changes can be produced by angiotensin II (ANG II) acting on angiotensin type I receptors, endothelin-1 (ET-1) acting on type A receptors (ETA-Rs) or cyclooxygenase (COX) dependent prostaglandins (PGs), and thromboxane A2 (TxA2) acting on thromboxane-prostanoid receptors (TP-Rs)8–11. TxA2 has been implicated in the hypertension, renal vasoconstriction and glomerulosclerosis of rats with CKD12 has been modeled in mice with surgically reduced renal mass (RRM)13, 14. This C57/BL6 mouse model has severe oxidative stress but maintains a normal conscious mean blood pressure (MBP) measured telemetrically over 3 months and has only a modest reduction in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) over 3 months14. Therefore, it is a convenient model to study early CKD without the confounding effects of hypertension or uremia. Moreover, TP-R −/− mice maintain a normal MBP measured telemetrically and basal phenotype which simplifies interpretation of results with this strain11, 15

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) upregulate COX-2 in the vessel wall9. Moreover, ROS react with nitric oxide (NO) to generate peroxynitrite that irreversibly inactivates prostacyclin synthase thereby redirecting COX-products to vasoconstrictor actions16. Indeed, COX-2 generates endoperoxides (PGH2) and TxA2 that activate TP-Rs in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) that, during increased ROS, mediate an endothelium-dependent contracting factor (EDCF) response9, 17. Thus, TP-R signaling can be downstream from increased ROS. Surprisingly, however, genetic deletion of TP-Rs prevented an increased excretion of the oxidative stress marker 8-isoprostane F2α in mice infused with ANGII11. Thus, TP-R signaling also can be upstream of increased ROS. ROS18 and CKD19 both increase ET-1 generation. However, the mechanisms interlinking TP-R activation, ROS and ET-1 generation are unclear20. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that ROS and ET-1generated in microvessels of mice with RRM depend on COX-2 generation of PGs and/or TxA2 that activate TP-Rs. These studies have translational impact because drugs that block TP-Rs are already in clinical trials with promising responses21. If they were found to reduce vascular contractility, remodeling, ROS and ET-1 generation in CKD, they could fill a therapeutic void to prevent CVD which is now the principal cause of death and disability in these patients.

Methods

Animal Preparation and Surgery

Male C57BL6 mice weighing 25 to 30 g (Charles River Laboratory, Germantown, MD), TP-R knockout (−/−), and TP-R wild-type (TP+/+) mice (C57/BL6J background, kind gift from Thomas Coffman, MD, Duke University, Chapel Hill, NC) were maintained on tap water and standard chow (Na+ content 0.4 g ·100g−1, Harlan Teklad) and allowed free access to tap water. All of the procedures conformed to the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by the NIH Institute for Laboratory Animal Research, and were approved by the Georgetown University Animal Care and Use Committee.

A 2-step surgical 5/6 nephrectomy procedure was used to create RRM under inhalational anesthesia with 2% isoflurane and oxygen mixed with room air in a vaporizer13, 14. Approximately, two thirds of the mass of the left kidney was ablated by stitching off each pole using an absorbable hemostat (Ethicon, Inc.). At a second surgery 1 week later, the right kidney was removed. SHAM-operated control mice (SHAM) were subjected to a similar 2-stage procedure without the removal of renal mass. Mice were studied after 3 months, at which time they had considerable oxidative stress with a 7-fold increase in excretion of 8-isoprostane F2α but an unchanged BP and only mild albuminuria, glomerulosclerosis, tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and a 33% reduction in measured overall glomerular filtration rate (GFR)13, 14.

Measurement of plasma endothelin 1 concentration

Plasma concentrations of ET-1 were measured using a Quantikine ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA22.

Measurement of urinary 8-isoprostane F2α (8-Iso), thromboxane B2 (TxB2), malondialdehyde (MDA), microalbumin, and creatinine

Mice were housed in metabolic cages (Nalgene Nunc International, Rochester, NY). Urine was collected for 24 hours into tubes containing antibiotics as described23, 24. 8-Iso and TxB2 in urine were quantified by ELISA (Enzo Life Science Inc. Farmingdale, NY) after purification, extraction, and measurement of individual recovery by spiking with radiolabelled PGE2, as described and validated previously against GC/MS24. MDA was measured by an assay kit (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI)17 and microalbumin by an ELISA kit (Exocell, Philadelphia, PA). Values were normalized with creatinine, which was measured by a urinary creatinine assay kit (Exocell, Philadelphia, PA) (see Online Data Supplement).

Protein expression of mesenteric resistance arterioles

The expression of ETA-R, p22phox, p47phox, COX-1 and -2, and TP-R of mesenteric resistance arterioles were quantified using specific antibodies as described13, 14, 23, 25, 26. (details see Online Data Supplement)

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA isolation and real-time quantitative PCR was performed as previously described with some modifications27. (details see Online Data Supplement)

Preparation and study of mesenteric resistance arterioles

Vessels (mean luminal diameter 125±3 µm and length 2 mm) were separated from the superior mesenteric bed, mounted in a wire myograph (M610, Danish myotechnology A/S; Aarhus, Denmark) and studied as described28 (see Online Data Supplement).

Experimental protocol

The vascular and luminal areas were measured as described28, 29. Concentration-response curves to phenylephrine (PE: 10−8 to 10−5 mol·L−1, α-adrenoceptor agonist), U-46,619 (10−9 to 10−6 mol·L−1, TP-Rs agonist,) and endothelin −1 (ET-1, 10−10 to 10−7 mol·L) were compared to vehicle. Since PE-mediated contractions were not enhanced in RRM, ET-1 was selected for further studies.

To examine the functional effects of cellular and mitochondrial ROS, vessels were incubated with vehicle, the membrane permeable redox cycling nitroxide tempol (10−4 mol·L−1, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), or the mitochondrial accumulated form MitoTEMPO (10−5 mol·L−1, Sigma, St. Louis, MO)30 for 30 minutes prior to testing with ET-1 (10−7 mol·L−1).

To examine the role of PGs and TP-Rs, concentration-dependent responses to ET-1 (10−7 mol·L−1) were obtained after incubation (30 min) with either vehicle, SC-560 (10−6 mol·L−1; SC, an inhibitor of COX-1, Sigma, St. Louis), paracoxib (10−5 mol·L−1; Para, an inhibitor of COX-2, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), SC+Para, OKY-046NA (10−5 mol·L−1; an inhibitor of TxA2 synthase (TxA2-S), Sigma, St. Louis, MO), or SQ-29,548 (10−6 mol·L−1; inhibitor of TP-Rs, Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI). These are fully effective concentrations7 (see online Data Supplement).

Endothelin-1-stimulated cellular and mitochondrial ROS in mesenteric resistance arterioles

ET-1 (10−7 mol·L−1)-induced cellular and mitochondrial ROS production were determined after loading with dihydroethidium (DHE) or MitoSox™ Red as described9, 31 and fluorescence quantified by PTI RatioMaster™ (Photon Technology International, London, Ontario, Canada) (see Online Data Supplement).

Prolonged effect of TP-Rs in mice with RRM

RRM or SHAM models were created in TP-R +/+ and −/− mice and studied 3 months after the surgery. Plasma ET-1, 24 hour urinary 8-Iso, TxB2, MDA, microalbumin, mesenteric arteriolar contractions to PE, ET-1, and U-46,619 and generation of cellular and mitochondrial ROS with ET-1 were obtained as described.

Chemicals and solutions

Agentswere purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MI) and dissolved in physiologic salt solution (PSS).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Cumulative concentration-response experiments were analyzed by nonlinear regression (curve fit) for repeated measurement and differences assessed by two-way, repeated-measures ANOVA with interaction to assess the effects of RRM vs SHAM, intervention vs vehicle or TP-R −/− vs TP-R +/+ and the interaction (the effects of the intervention or genotype on the response to RRM). This was followed, if appropriate, with Bonferroni post hoc t-tests for multiple comparisons. A probability value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Body, kidney and heart weights, mesenteric resistance arteriole remodeling, plasma endothelin-1and renal excretion of biomarkers (Table 1)

Table 1.

Basal parameters, plasma endothelin-1 and 24-hour urinary excretion in C57BL/6 mice: comparison of Sham operated and reduced renal mass mice

| Parameter | SHAM | RRM | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (BWt) (g) | 32.6±0.8 | 33.1±0.9 | NS |

| Kidney weight/BWt (mg·g−1) | 6.6±0.2 | 7.8±0.3 | <0.05 |

| Heart weight/BWt (mg·g−1) | 4.5±0.2 | 4.4±0.2 | NS |

| Aorta weight/BWt (mg·g−1) | 0.13±0.007 | 0.15±0.008 | NS |

| Vessel lumen CSA (×1000 µm2) | 99.6±31.3 | 75.4±15.0 | NS |

| Vessel media CSA (×1000 µm2) | 12.9±3.7 | 17.7±2.7 | NS |

| Vessel media:lumen (µm2·µm−2) | 0.17±0.02 | 0.27±0.01 | <0.01 |

| Plasma endothelin-1 (pg/ml) | 1.6±0.3 | 3.4±0.3 | <0.05 |

| Urinary 8- isoprostane F2α /creatinine (ng·mg−1) | 2.8±0.38 | 5.1±0.6 | <0.05 |

| Urinary malondialdehyde /creatinine (nmol·mg−1) | 48.0±3.4 | 69.2±6.8 | <0.05 |

| Urinary TxB2/creatinine (ng·mg−1) | 2.01±0.15 | 2.52±0.13 | <0.05 |

| Urinary microalbumin/creatinine (ug·mg−1) | 7.3±0.3 | 12.6±2.0 | <0.05 |

Mean ±SEM values, (n=6 /group). CSA: cross-section area

Mice with RRM had normal body, heart and aorta weights but, despite removal of two-thirds of the left kidney to create RRM, its mass at 3 months exceeded that of SHAM mice, as reported previously14. Mice with RRM had an increased media:lumen ratio of mesenteric resistance arterioles and increased plasma ET-1 and renal excretions of 8-Iso, MDA, TxB2, and microalbumin (P<0.05).

Protein expression in mesenteric resistance arterioles (Table 2 and supplementary Figures Suppl 1, Suppl 2 and Suppl 3)

Table 2.

Expression of proteins and mRNA in mesenteric resistance arterioles from C57BL/6 mice

| A | Proteins | SHAM (n=5) |

RRM (n=5) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | N=5 | N=5 | ||

| Endothelin A-R | 0.36±0.06 | 0.52±0.04 | <0.01 | |

| p47phox | 0.37±0.04 | 0.30±0.04 | NS | |

| p22phox | 0.08±0.02 | 0.69±0.15 | <0.01 | |

| TP-R | 0.30±0.04 | 0.52±0.04 | <0.01 | |

| COX-1 | 0.28±0.03 | 0.33±0.03 | NS | |

| COX-2 | 0.42±0.12 | 1.20±0.27 | <0.05 |

| B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | SHAM (n=5) |

RRM (n=5) |

P value | |

| Endothelin A-R | 1.02±0.05 | 1.89±0.17 | <0.01 | |

| Preproendothelin-1 | 1.01±0.08 | 1.46±0.13 | <0.05 | |

| p22phox | 1.01±0.05 | 2.42±0.13 | <0.005 | |

| TP-R | 1.03±0.05 | 0.96±0.01 | <0.01 | |

| COX-1 | 0.28±0.03 | 0.33±0.03 | NS | |

| COX-2 | 1.01±0.09 | 2.35±0.28 | <0.05 | |

Mean ±SEM values as fold relative to beta-actin for protein (see figures in supplements S1 to S3 for blots) or relative to 18s rRNA for mRNA (see figure in supplement S4). Endothelin A-R, endothelin type A receptor; TP-R, thromboxane-prosanoid receptor; COX, cyclooxygenase.

Vessels from mice with RRM had increased protein expression of ETA-R, p22phox, COX-2, and TP-R but no significant change in p47phox or COX-1.

Gene expression in mesenteric resistance arterioles (Table 2 and supplementary figure S4)

Vessels from mice with RRM had increased mRNA expression of ETA-R, preproendothelin-1, p22phox and COX-2 but no significant change in COX-1 or TP-R.

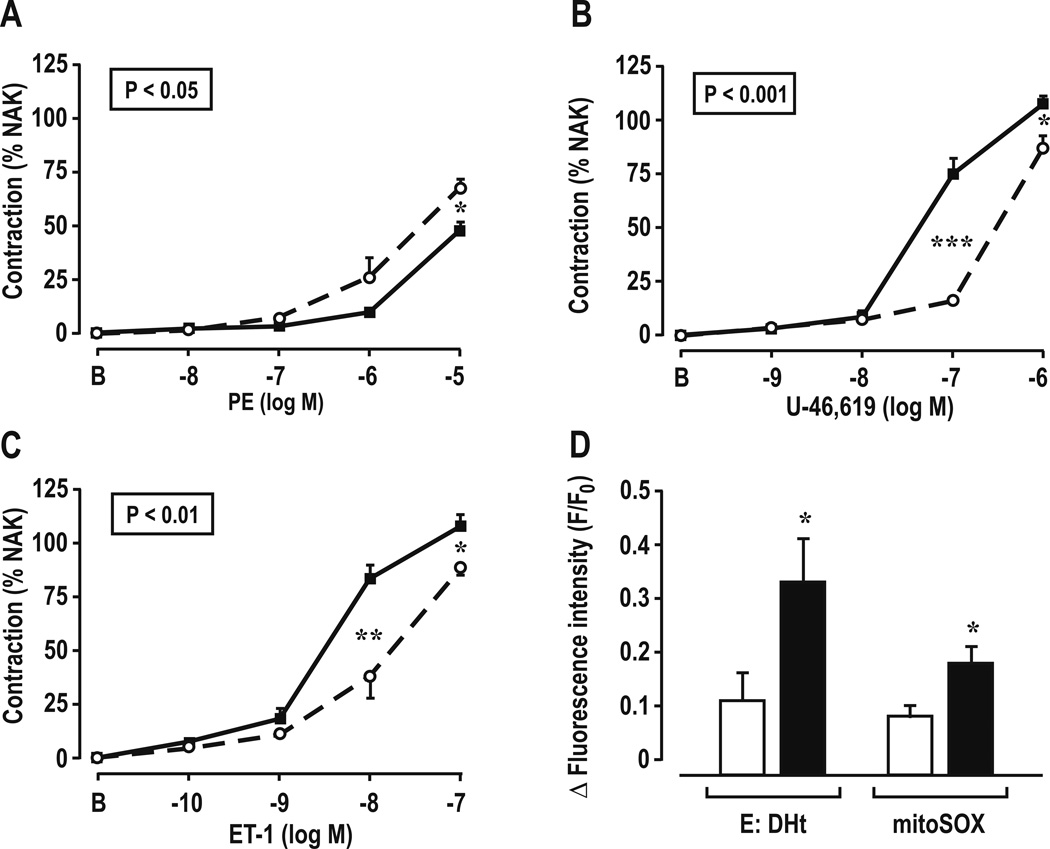

Contractions and ROS generation with ET-1 in mesenteric resistance arterioles (Figure 1 and Table 3)

Figure 1.

Concentration-response relationships for phenylephrine (Panel A), U-46,619 (Panel B), endothelin-1 (Panel C), and cellular and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation with 10−7 mol·L−1 endothelin-1 (Panel D) in mesenteric resistance arterioles from SHAM (open circles and broken lines or open boxes) and reduced renal mass mice (closed circles and continuous lines or shaded boxes). Comparing groups: *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01, ***, P<0.005. E:Dht; ethidium: dihydroethidium fluorescence ratio.

Table 3.

Maximum vascular contractions and ROS generation of mesenteric arterioles in C57BL/6 mice: Comparison of sham operated and reduced renal mass mice

| Stimulus | SHAM | RRM | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE (10−5M) contraction (%) | 67.8±3.8 | 48.1±3.4 | <0.05 |

| U-46,619 (10−6M) contraction (%) | 87.1±5.9 | 118.0±2.6 | <0.01 |

| ET-1 (10−7M) contraction (%) | 89.1±4.0 | 108.1±5.1 | <0.05 |

| ET-1 (10−7M) cellular ROS generation (Eth/DHE,Δf/f0) | 0.13±0.03 | 0.33±0.09 | <0.05 |

| ET-1 (10−7M) mitochondrial ROS generation (mitoSOX, Δf/f0) | 0.08±0.02 | 0.17±0.02 | <0.05 |

Mean ± SEM values (n = 6 per group). PE, phenylephrine; ET-1, endothelin-1, ROS, reactive oxygen species

Vessels from mice with RRM had reduced contractions to PE, but increased contractions to U-46,619 and ET-1 and generated more cellular and mitochondrial ROS with 10−7 mol·L−1 of ET-1 than SHAM mice.

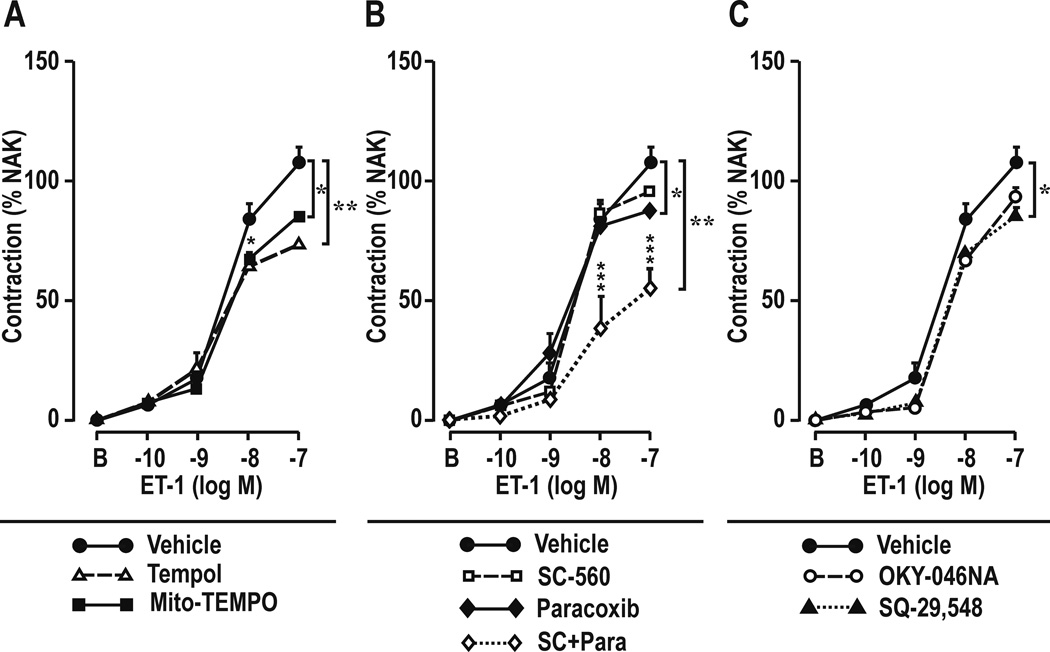

Effect of metabolism of cellular or mitochondrial ROS or blockade of COXs, TxA2-S, or TP-Rs on contractions to ET-1 in mesenteric resistance arterioles (Table 4 and Figure 2)

Table 4.

Effects of metabolism of cellular or mitochondrial ROS or antagonist of cyclooxygenase-1 or -2, thromboxane A2 synthase or thromboxane-prostanoid receptors on endothelin-1 (10−7 mol·L−1) contractions of mesenteric resistance arteries from C57BL/6 mice: comparison of sham operated and reduced renal mass mice

| Treatment | Contraction (%) | By ANOVA, effects of : | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHAM | RRM | RRM | Treatment | Interaction | |

| Vehicle | 89.2±4.1 | 108.8±5.1 | P<0.01 | P<0.05 | |

| Tempol | 79.0±3.4 | 73.6±2.5 | P<0.05 | P<0.01 | P<0.01 |

| MitoTEMPO | 92.2±6.7 | 85.1±1.5 | P<0.05 | P<0.05 | P<0.05 |

| SC-560 | 84.1±5.4 | 96.1.±2.3 | P<0.05 | NS | NS |

| Paracoxib | 79.1.±3.3 | 88.2±3.5 | P<0.05 | P<0.05 | NS |

| SC-560+Paracoxib | 83.1±5.1 | 55.6±7.8 | P<0.05 | P<0.01 | P<0.05 |

| OKY-046NA | 85.1±4.3 | 94.4.±3.4 | P<0.05 | NS | NS |

| SQ-29,548 | 87.8±3.2 | 85.3±4.6 | P<0.05 | P<0.05 | P<0.05 |

Mean ± SEM values (n = 6 per group)

Figure 2.

Contractile concentration responses to endothelin-1 in mesenteric resistance arterioles from mice with reduced renal mass after bath addition of: Panel A. Reactive oxygen species inhibitors: vehicle, tempol (10−4 mol·l−1) or mitoTEMPO (10−4 mol·l−1) or Panel B, cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors: SC-560 (10−6 mol·l−1; COX-1 inhibitor), paracoxib (10−5 mol·l−1; COX-2 inhibitor) or SC-560 plus paracoxib; or Panel C, thromboxane inhibitors: OKY-046NA (10−5 mol·l−1; thromboxane A2 synthase inhibitor), or SQ-29,548 (10−6 mol·l−1; thromboxane-prostanoid inhibitor). Compared with vehicle: *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.005

The enhanced contractions to ET-1 in vessels from mice with RRM were reduced by incubation with tempol, MitoTEMPO or with paracoxib (a selective COX-2 inhibitor) alone or plus SC-560 (a selective COX-1 inhibitor) or SQ-29,548 (a TP-R inhibitor) but not with SC-560 alone or OKY-046NA (a TxA2-S inhibitor).

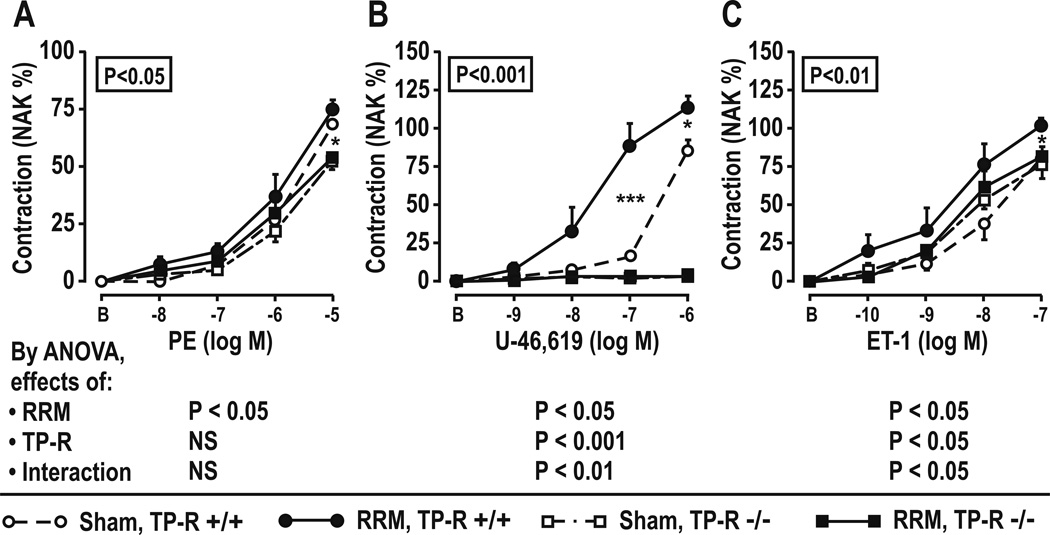

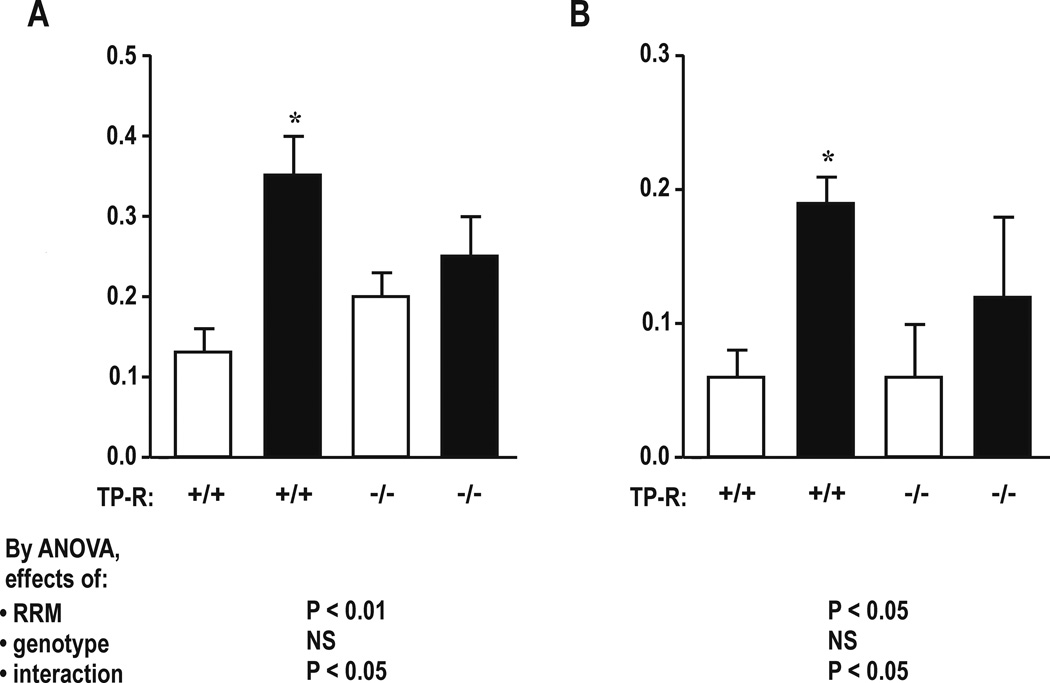

Effect of TP-Rs in mice with RRM (Table 5 and Figures 3 and 4)

Table 5.

Basal parameters, plasma endothelin-1, renal excretions of makers of reactive oxygen species, thromboxane and microalbumin, vessel structure, maximum vascular contractions and reactive oxygen species generation in mesenteric resistance arterioles: effects of reduced renal mice and thromboxane-prostanoid receptor knockout

| Parameter | TP-R+/+ | TP-R−/− | By ANOVA, effect of | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHAM | RRM | SHAM | RRM | RRM | Genotype | Interaction | |

| Body weight (BWt) (g) | 29.4±0.5 | 30.5±1.6 | 29.7±1.4 | 30.3±1.6 | NS | NS | NS |

| Kidney weight /BWt (mg·g−1) | 6.1±0.3 | 9.4±0.5‡ | 7.1±0.2 | 8.9±0.4† | <0.005 | NS | NS |

| Heart weight/BWt (mg·g−1) | 4.7±0.1 | 5.2±0.2 | 4.3±0.2 | 4.5±0.4 | NS | NS | NS |

| Aorta weight/ BWt (mg·g−1) | 0.14±0.005 | 0.15±0.008 | 0.15±0.006 | 0.16±0.007 | NS | NS | NS |

| Plasma endothelin −1 (pg/ml) | 2.2±0.3 | 4.6±0.2‡ | 3.0±0.2 | 3.1±0.5 | <0.01 | NS | <0.01 |

| Urinary 8-isoprostane F2α /creatinine (ng·mg−1) | 1.43±0.18 | 5.36±0.62‡ | 1.79±0.11 | 3.32±0.04*¶ | P<0.005 | P<0.05 | P<0.01 |

| Urinary malondialdehyde /creatinine (nmol·mg−1) | 47.7±9.1 | 72.5±7.5* | 52.1±5.3 | 53.1±3.4‖ | P<0.05 | NS | <0.05 |

| Urinary TxB2/creatinine (ng·mg−1) | 1.2±0.1 | 2.7±0.2* | 0.9±0.1 | 2.1±0.1* | P<0.01 | P<0.05 | P<0.05 |

| Urinary microalbumin/creatinine (µg·mg−1) | 56±4 | 124±36* | 34±8 | 44±6¶ | P<0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Vessel lumen CSA (×1000 µm2) | 89.6±4.2 | 71.4±4.1 | 80.6±6.2 | 75.4±3.0 | NS | NS | NS |

| Vessel media CSA (×1000 µm2) | 12.0±1.2 | 16.4±2.5 | 11.5±2.0 | 11.4±2.0 | NS | NS | NS |

| Vessel media:lumen (µm2: µm2) | 0.13±0.01 | 0.23±0.02† | 0.14±0.02 | 0.16±0.02‖ | P<0.05 | NS | <0.05 |

| PE (10−5M) contraction (%) | 76.1±5.9 | 64.4±7.3* | 71.7±3.3 | 62.1±4.2* | NS | NS | NS |

| U-46,619 (10−6M) contraction (%) | 94.3±4.5 | 110.1±3.2* | 1.7±0.7# | 2.8±3.3# | P<0.05 | P<0.001 | P<0.01 |

| ET-1 (10−7M) contraction (%) | 81.3±4.5 | 106.7±2.3* | 84.7±4.7 | 95.5±3.5¶ | P<0.05 | P<0.01 | P<0.05 |

| ET-1 (10−7M) cellular ROS generation (Eth/DHE, Δf/f0) | 0.13±0.03 | 0.35±0.05† | 0.20±0.03 | 0.25±0.05 | P<0.01 | NS | P<0.05 |

| ET-1 (10−7M) mitochondrial ROS generation (mitoSOX, Δf/f0) | 0.06±0.02 | 0.19±0.02* | 0.06±0.04 | 0.12±0.06 | P<0.05 | NS | P<0.05 |

Mean ± SEM values (n = 6 per group). CSA: cross-sectional area. Compared to SHAM:

, P<0.05,

, P<0.01,

P<0.001,

Compared to equivalent TP+/+:

, P<0.05;

, P<0.01,

, P<0.001

Figure 3.

Effect of thromboxane-prostanoid receptors and reduced renal mass on contractile responses in mesenteric resistance arterioles. Data from SHAM (open symbols) or RRM (shaded symbols) in TP-R +/+ (circles) or TP-R −/− (square) mice. Mean± SEM values (n=6 per group). Compared with TP-R +/+: *P<0.05; ***, P<0.005.

Figure 4.

Effect of thromboxane-prostanoid receptors and reduced renal mass on cellular and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation with 10−7 mol·l−1 endothelin-1 in mesenteric resistance arterioles. Mean± SEM values (n=6 per group) for cellular ROS generation (Panel A) and mitochondrial ROS generation (Panel B) from TP-R +/+ or TP-R −/− mice from SHAM (open boxes) or RRM (shaded boxes) groups. Compared to TP-R +/+: *P<0.05.

Similar to C57/BL6 mice of the prior series, TP+/+ mice with RRM had increased plasma ET-1 and increased excretion of 8-Iso, MDA, TxB2 and microalbumin (Table 5). Their mesenteric resistance arterioles had increased vascular remodeling, decreased contractions to PE, but increased contractions to U-46,619 and ET-1(Figure 3) and increased cellular ROS and mitochondrial ROS with ET-1 (Figure 4). TP-R −/− abolished all of these effects of RRM, except for the reduced PE contractions.

Discussion

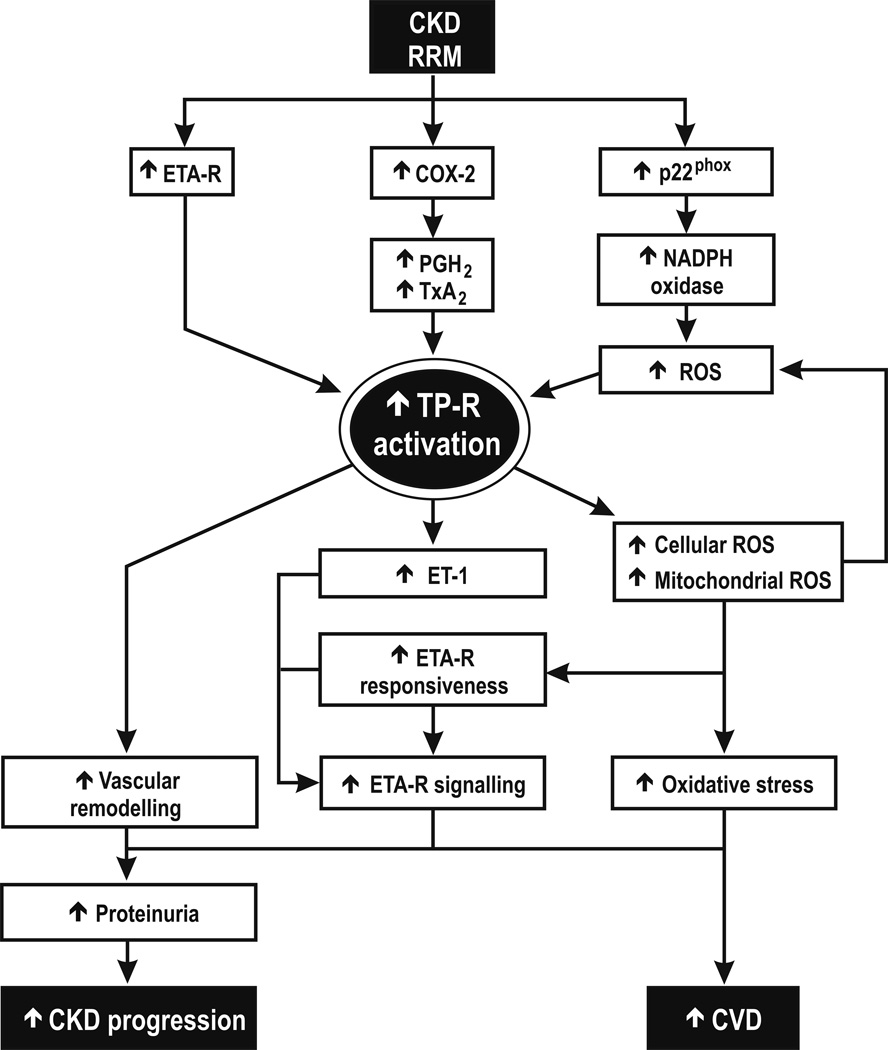

We confirm that 3 months of RRM in C57Bl/6 mice increases oxidative stress, albuminuria and growth of the remaining renal mass13, 14. The main new findings are that these mice had increased plasma ET-1 and generated more TxA2, their mesenteric resistance arterioles were considerably remodeled and had reduced contractions to PE, but enhanced contractions to U-46,619 and ET-1 and enhanced cellular and mitochondrial ROS with ET-1. The enhanced ET-1 contractions were dependent on cellular and mitochondrial ROS and on TP-Rs and products of COX-2>-1. Unlike TP-R +/+, TP-R−/− mice with RRM did not have significantly enhanced plasma levels of ET-1 or enhanced contractions or cellular or mitochondrial ROS in response to ET-1 and did not have vascular remodeling. Thus, TP-Rs mediate enhanced generation of ET-1 and microvascular ROS and enhanced contractility and remodeling in this mouse model of CKD. Figure 5 presents a schema for the proposed central role for TP-Rs in progressive CKD.

Figure 5.

A flow diagram to demonstrate the potential central role for thromboxane-prostanoid receptors in mediating the increased endothelin-1, reactive oxygen species and microvascular remodeling that may contribute to progression of chronic kidney disease.

TP-Rs are activated by PGH2 (a primary product of COX-1 and-2), TxA2 and by the stable mimetic, U-46,619. The vascular protein expression of both COX-2 and TP-Rs was upregulated in mice with RRM and the enhanced responsiveness to ET-1 was dependent on COX-2 and TP-Rs (although blockade of COX-1 with COX-2 was more effective than COX-2 alone, suggesting some adaptive interaction). Since blockade of TxA2-S did not prevent enhanced ET-1 contractions, it is likely that PGH2, generated by COX-2>-1 was the principal PG activating the TP-Rs. Activation of the TP-Rs enhances the generation of PGs and TxA2 which further activate the TP-R in a feed-forward manner32, 33. This may account for the reduced excretion of TxB2 in TP-R −/− mice with RRM. Although mice with RRM had increased TP-R protein expression and increased TP-R responses to U-46,619, TP-R mRNA was unchanged. This may relate to oxidative stress that post-transcriptionally prevents TP-R protein degradation and enhances its membrane expression34.

The enhanced contractions to ET-1 and U-46,619 in vessels from mice with RRM were probably not a consequence of vascular remodeling since contractions to PE were actually diminished. Adrenergic agonists usually do not provoke vascular oxidative stress35. Moreover, the structural and functional changes in mice with RRM were likely independent of BP and uremia since prior telemetric measurement of mean arterial pressure (MAP) were unchanged after 3 months of RRM and the global GFR was reduced by only 33%13, 14

ET-1 is generated in vascular endothelial cells. Its production is increased by ROS18, 36 and CKD19. Whereas ANG II increases ROS in VSMCs largely by activation of NADPH oxidase35, ET-1 also activates other source of ROS including the mitochondria37, 38. The present study demostrates that ET-1 activated ethidium: dihydroethiduim fluorescence ratio and mitoSOX™ Red fluorescence39 and both tempol (distributed throughout the cell)40, 41 and mitoTEMPO (partitioned into mitochondria)39–41 prevented the enhanced contractility to ET-1 in vessels from mice with RRM. Thus, both sources of ROS were activated in mice with RRM and apparently both contributed to enhanced contractions to ET-1. p22phox is an essential chaperone protein for neutrophial oxidases (NOXs)26, 42. It was strongly upregulated in vessels from mice with RRM and could account for the observed increase in cellular ROS since in vivo silencing of p22phox prevents the progressive increase in excretion of 8-Iso and the hypertension of rats infused with ANG II26. NOX-2 is expressed in resistance arterioles and the kidney42 and was upregulated > 3-fold in the kidneys of mice with RRM14. An uncoupled endothelial NOS may have contributed also to the increased ROS43.

In contrast to TP-R +/+, TP-R −/− mice with RRM did not have significantly increased plasma levels of ET-1 or excretions of MDA, TxB2 or microalbumin or significantly enhanced cellular or mitochondrial ROS or contractions to ET-1 (although there were trends suggesting some residual effects). However, the reduced contractions to PE persisted in TP-R-1 −/− mice with RRM which might represent downregulation of vascular α-adrenoreceptors during enhanced sympathetic nervous activity in RRM44. The absence of vascular remodeling in arterioles from TP-R −/− mice with RRM may represent less vascular ROS45, 46. Vascular remodeling in mice with ANGII is dependent on TP-Rs in VSMCs47. Our findings extend microvascular studies9 that have reported that ROS enhance TP-R activity and responsiveness to ANG II and ET-1 by demonstrating that this pattern occurs in a model of CKD and that vascular TP-Rs are required to generate cellular and mitochondrial ROS with ET-1. Thus, TP-Rs are both upstream and downstream of ROS and thereby may play essential mediating and reinforcing roles in the generation of ROS from cellular and mitochondrial sources. They could thereby enhance remodeling and contractility of microvessels in CKD.

Perspective

Future CVD events are predicated by endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodeling48, 49 which are frequently accompanied by oxidative stress49, as in CKD50. ROS7, 29, 50, ET-119 and TxA214, 51, 52 are all increased in patients with CKD. The vascular remodeling, enhanced ROS and responsiveness to ET-1 and thromboxane in mice with RRM were prevented by genetic deletion of TP-Rs. Thus TP-R antagonists, which have already been used in clinical trials21, could be novel drugs to prevent vascular oxidative stress and CVD in patients with CKD.

ETA-R blockade improves renal function19 and reduces glomerulosclerosis in a rat model of RRM53 and markedly reduces albuminuria in patients with diabetic54 and non-diabetic55 CKD. Since we now show the importance of TP-Rs in activating the ET-1 system in RRM, TP-R antagonists may reduce renal disease progression in addition to vascular injury.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What is New?

The plasma levels of ET-1, the microvascular protein expression of p22phox, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), TP-Rs and endothelin-A receptors, the remodeling and the contractions to both ET-1 and thromboxane are increased in a mouse model of CKD.

The increases in microvascular cellular and mitochondrial ROS of mice with RRM depend on TP-Rs

TP-R gene deletion prevents ET-1 generation, microvascular remodeling, enhanced contractile response and ROS generation in mice with RRM.

What is Relevant?

The results from clinical trials in patients treated with TP-R antagonists are promising. Vascular TP-Rs are novel targets to correct the remodeling, dysfunction and oxidative stress in microvessels that precedes cardiovascular disease in patients with CKD.

Summary

Mice with RRM have increased ET-1 and microvascular remodeling and enhanced ET-1-induced cellular and mitochondrial ROS and contractions that are mediated by COX-2 products activating TP-Rs. Thus, TP-Rs can be upstream from ROS and contribute to vascular dysfunction in CKD.

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding

This work was supported by a grant to DW from the Marriott Cardiovascular Research Fellowship, to CSW and WJW from the NIDDK (DK-049870 and DK-036079) and the NHLBI (HL-68686 and HL-089583) and to CSW by funds from the George E. Schreiner Chair of Nephrology and the Hypertension, Kidney and Vascular Research Center and to CW by a Chinese Government Scholarship Program.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Santoro A, Mandreoli M. Chronic renal disease and risk of cardiovascular morbidity-mortality. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2014;39:142–146. doi: 10.1159/000355789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landray MJ, Emberson JR, Blackwell L, Dasgupta T, Zakeri R, Morgan MD, Ferro CJ, Vickery S, Ayrton P, Nair D, Dalton RN, Lamb EJ, Baigent C, Townend JN, Wheeler DC. Prediction of esrd and death among people with ckd: The chronic renal impairment in birmingham (crib) prospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:1082–1094. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park J, Ahmadi SF, Streja E, Molnar MZ, Flegal KM, Gillen D, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Obesity paradox in end-stage kidney disease patients. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;56:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaziri ND, Norris KC. Reasons for the lack of salutary effects of cholesterol-lowering interventions in end-stage renal disease populations. Blood Purif. 2013;35:31–36. doi: 10.1159/000345176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen DL, Townsend RR. Hypertension and kidney disease: What do the data really show? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2012;14:462–467. doi: 10.1007/s11906-012-0285-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang D, Strandgaard S, Borresen ML, Luo Z, Connors S, Yan Q, Wilcox CS. Asymmetric dimethylarginine and lipid peroxidation products in early autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kid Dis. 2008;51:184–191. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D, Iversen J, Wilcox CS, Strandgaard S. Endothelial dysfunction and reduced nitric oxide in resistance arteries in autosomal polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1381–1388. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D, Chen Y, Chabrashvili T, Aslam S, Borrego L, Umans J, Wilcox CS. Role of oxidative stress in endothelial dysfunction and enhanced responses to Ang II of afferent arterioles from rabbits infused with Ang II. J Am Soc of Nephrol. 2003;14:2783–2789. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000090747.59919.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang D, Chabrashvili T, Wilcox CS. Enhanced contractility of renal afferent arterioles from angiotensin-infused rabbits: Roles of oxidative stress, thromboxane-prostanoid receptors and endothelium. Cir Res. 2004;94:1436–1442. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000129578.76799.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Modlinger PS, Wilcox CS, Aslam S. Nitric oxide, oxidative stress and progression of chronic renal failure. Sem in Nephrol. 2004;24:354–365. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawada N, Dennehy K, Solis G, Modlinger P, Hamel R, Kawada JT, Aslam S, MOriyama T, Imai E, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Tp receptors regulate renal hemodynamics during angiotensin ii slow pressor response. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F753–F759. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00423.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Purkerson ML, Joist JH, Yates J, Valdes A, Morrison A, Klahr S. Inhibition of thromboxane synthesis ameliorates the progressive kidney disease of rats with subtotal renal ablation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:193–197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai E, Onozato ML, Solis G, Aslam S, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Myogenic responses of mouse isolated perfused renal afferent arterioles: Effects of salt intake and reduced renal mass. Hypertens. 2010;55:983–989. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.149120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai EY, Luo Z, Onozato ML, Rudolph EH, Solis G, Jose PA, Wellstein A, Aslam S, Quinn MT, Griendling K, Le T, Li P, Palm F, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Effects of the antioxidant drug tempol on renal oxygenation in mice with reduced renal mass. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303:F64–F74. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00005.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnermann J, Traynor T, Pohl H, Thomas DW, Coffman TM, Briggs JP. Vasoconstrictor responses in thromboxane receptor knockout mice: Tubuloglomerular feedback and ureteral obstruction. Acta Physiol Scand. 2000;168:201–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schildknecht S, Ullrich V. Peroxynitrite as regulator of vascular prostanoid synthesis. Arch Biochem and Biophys. 2009;484:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang D, Luo Z, Wang X, Jose PA, Falck JR, Welch WJ, Aslam S, Teerlink T, Wilcox CS. Impaired endothelial function and microvascular asymmetrical dimethylarginine in angiotensin ii-infused rats: Effects of tempol. Hypertens. 2010;56:950–955. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.157115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen HC, Guh JY, Shin SJ, Tsai JH, Lai YH. Reactive oxygen species enhances endothelin-1 production of diabetic rat glomeruli in vitro and in vivo. J Lab Clin Med. 2000;135:309–315. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2000.105616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohan DE, Barton M. Endothelin and endothelin antagonists in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernanz R, Briones AM, Salaices M, Alonso MJ. New roles for old pathways? A circuitous relationship between reactive oxygen species and cyclo-oxygenase in hypertension. Clin Sci (London, England : 1979) 2014;126:111–121. doi: 10.1042/CS20120651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lesault PF, Boyer L, Pelle G, Covali-Noroc A, Rideau D, Akakpo S, Teiger E, Dubois-Rande JL, Adnot S. Daily administration of the tp receptor antagonist terutroban improved endothelial function in high-cardiovascular-risk patients with atherosclerosis. Br. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71:844–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rafnsson A, Bohm F, Settergren M, Gonon A, Brismar K, Pernow J. The endothelin receptor antagonist bosentan improves peripheral endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and microalbuminuria: A randomised trial. Diabetologia. 2012;55:600–607. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2415-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welch WJ, Peng B, Takeuchi K, Abe K, Wilcox CS. Salt loading enhances rat renal txa2/pgh2 receptor expression and tgf response to u-46,619. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:F976–F983. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.6.F976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schnackenberg C, Wilcox CS. Two-week administration of tempol attenuates both hypertension and renal excretion of 8-isoprostaglandin f2α. Hypertens. 1999;33:424–428. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo Z, Chen Y, Chen S, Welch WJ, Andresen BT, Jose PA, Wilcox CS. Comparison of inhibitors of superoxide generation in vascular smooth muscle cells. British J Pharmacol. 2009;157:935–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Modlinger P, Chabrashvili T, Gill PS, Mendonca M, Harrison DG, Griendling KK, Li M, Raggio J, Wellstein A, Chen Y, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Rna silencing in vivo reveals role of p22phox in rat angiotensin slow pressor response. Hypertens. 2006;47:238–244. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000200023.02195.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luo Z, Teerlink T, Griendling K, Aslam S, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Angiotensin ii and nadph oxidase increase adma in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertens. 2010;56:498–504. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.152959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang D, Chabrashvili T, Borrego L, Aslam S, Umans JG. Angiotensin ii infusion alters vascular function in mouse resistance vessels: Roles of o2.- and endothelium. J Vasc Res. 2006;43:109–119. doi: 10.1159/000089969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang D, Iversen J, Strandgaard S. Contractility and endothelium-dependent relaxation of resistance vessels in polycystic kidney disease rats. J Vasc Res. 1999;36:502–509. doi: 10.1159/000025693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaffer OA, Carter AB, Sanders PN, Dibbern ME, Winters CJ, Murthy S, Ryan AJ, Rokita AG, Prasad AM, Zabner J, Kline JN, Grumbach IM, Anderson ME. Mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant therapy decreases tgfbeta mediated collagen production in a murine asthma model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0519OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pung YF, Rocic P, Murphy MP, Smith RA, Hafemeister J, Ohanyan V, Guarini G, Yin L, Chilian WM. Resolution of mitochondrial oxidative stress rescues coronary collateral growth in zucker obese fatty rats. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:325–334. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folger WH, Lawson D, Wilcox CS, Mehta JL. Response of rat thoracic aortic rings to thromboxane mimetic u-46,619: Roles of endothelium-derived relaxing factor and thromboxane a2 release. J Pharmacol and Exp Ther. 1991;258:669–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilcox CS, Folger WH, Welch WJ. Renal vasoconstriction with u-46,619: Role of arachidonate metabolites. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;5:1120–1124. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V541120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valentin F, Field MC, Tippins JR. The mechanism of oxidative stress stabilization of the thromboxane receptor in cos-7 cells. J Bio Chem. 2004;279:8316–8324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajagopalan S, Kurz S, Munzel T, Tarpey M, Freeman BA, Griendling KK, Harrison DG. Angiotensin ii-mediated hypertension in the rat increases vascular superoxide production via membrane nadh/nadph oxidase activation. Contribution to alterations of vasomotor tone. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1916–1923. doi: 10.1172/JCI118623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kisanuki YY, Emoto N, Ohuchi T, Widyantoro B, Yagi K, Nakayama K, Kedzierski RM, Hammer RE, Yanagisawa H, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Suzuki T, Yanagisawa M. Low blood pressure in endothelial cell-specific endothelin 1 knockout mice. Hypertens. 2010;56:121–128. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.138701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Callera GE, Tostes RC, Yogi A, Montezano AC, Touyz RM. Endothelin-1-induced oxidative stress in doca-salt hypertension involves nadph-oxidase-independent mechanisms. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;110:243–253. doi: 10.1042/CS20050307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viel EC, Benkirane K, Javeshghani D, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Xanthine oxidase and mitochondria contribute to vascular superoxide anion generation in doca-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. Heart and Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H281–H288. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00304.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuznetsov AV, Kehrer I, Kozlov AV, Haller M, Redl H, Hermann M, Grimm M, Troppmair J. Mitochondrial ros production under cellular stress: Comparison of different detection methods. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;400:2383–2390. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-4764-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearlman A, Wilcox CS, Chen Y. Reduction of oxidative stress-induced vasoconstriction by tempol is mediated by hydrogen peroxide. Hypertens. 2006;48:e34. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilcox CS. Effects of tempol and redox-cycling nitroxides in models of oxidative stress. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;126:119–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Araujo M, Wilcox CS. Oxidative stress in hypertension: Role of the kidney. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:74–101. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landmesser U, Dikalov S, Price SR, McCann L, Fukai T, Holland SM, Mitch WE, Harrison DG. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1201–1209. doi: 10.1172/JCI14172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campese VM. A new model of neurogenic hypertension caused by renal injury: Pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2003;7:167–171. doi: 10.1007/s10157-003-0238-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Touyz RM, Tabet F, Schiffrin EL. Redox-dependent signalling by angiotensin ii and vascular remodelling in hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2003;30:860–866. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2003.03930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zafari AM, Ushio-Fukai M, Akers M, Yin Q, Shah A, Harrison DG, Taylor WR, Griendling KK. Role of nadh/nadph oxidase-derived h2o2 in angiotensin ii-induced vascular hypertrophy. Hypertens. 1998;32:488–495. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sparks MA, Makhanova NA, Griffiths RC, Snouwaert JN, Koller BH, Coffman TM. Thromboxane receptors in smooth muscle promote hypertension, vascular remodeling, and sudden death. Hypertens. 2013;61:166–173. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.193250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rizzoni D, Porteri E, Boari GE, De CC, Sleiman I, Muiesan ML, Castellano M, Miclini M, gabiti-Rosei E. Prognostic significance of small-artery structure in hypertension. Circulation. 2003;108:2230–2235. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095031.51492.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schiffrin EL. Vascular remodeling in hypertension: Mechanisms and treatment. Hypertens. 2012;59:367–374. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.187021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oberg B, McMenamin E, Lucas FL, McMonagle E, Morrow J, Ikizler TA, Himmelfarb J. Increased prevalence of oxidant stress and inflammation in patients with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1009–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilcox CS, Lin L. Vasoconstrictor prostaglandins in angiotensin-dependent and renovascular hypertension. J Nephrol. 1993;6:124–133. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benndorf RA, Schwedhelm E, Gnann A, Taheri R, Kom G, Didie M, Steenpass A, Ergun S, Boger RH. Isoprostanes inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor-induced endothelial cell migration, tube formation, and cardiac vessel sprouting in vitro, as well as angiogenesis in vivo via activation of the thromboxane a(2) receptor: A potential link between oxidative stress and impaired angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2008;103:1037–1046. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.184036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benigni A, Zoja C, Corna D, Orisio S, Longaretti L, Bertani T, Remuzzi G. A specific endothelin subtype a receptor antagonist protects against injury in renal disease progression. Kidney Int. 1993;44:440–444. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Zeeuw D, Coll B, Andress D, Brennan JJ, Tang H, Houser M, Correa-Rotter R, Kohan D, Lambers Heerspink HJ, Makino H, Perkovic V, Pritchett Y, Remuzzi G, Tobe SW, Toto R, Viberti G, Parving HH. The endothelin antagonist atrasentan lowers residual albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:1083–1093. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dhaun N, MacIntyre IM, Kerr D, Melville V, Johnston NR, Haughie S, Goddard J, Webb DJ. Selective endothelin-a receptor antagonism reduces proteinuria, blood pressure, and arterial stiffness in chronic proteinuric kidney disease. Hypertens. 2011;57:772–779. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.167486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.