Abstract

Objective

To compare patterns of cognitive decline in older Latinos and non-Latinos.

Method

At annual intervals for a mean of 5.7 years, older Latino (n=104) and non-Latino (n=104) persons of equivalent age, education, and race completed a battery of 17 cognitive tests from which previously established composite measures of episodic memory, semantic memory, working memory, perceptual speed, and visuospatial ability were derived.

Results

In analyses adjusted for age, sex, and education, performance declined over time in each cognitive domain, but there were no ethnic group differences in initial level of function or annual rate of decline. There was evidence of retest learning following the baseline evaluation, but neither the magnitude nor duration of the effect was related to Latino ethnicity, and eliminating the first two evaluations, during which much of retest learning occurred, did not affect ethnic group comparisons. Compared to the non-Latino group, the Latino group had more diabetes (38.5% vs 25.0, χ2 [1] = 4.4, p=0.037), fewer histories of smoking (24.0% vs 39.4%, χ2 [1]= 5.7, p=0.017), and lower childhood household socioeconomic level (−0.410 vs −0.045, t [185.0] = 3.1, p=0.002), but controlling for these factors did not affect results.

Conclusion

Trajectories of cognitive aging in different abilities are similar in Latino and non-Latino individuals of equivalent age, education, and race.

Keywords: cohort studies, longitudinal studies, ethnic groups, Latinos, cognition, aging

Introduction

Most research on racial and ethnic differences in cognition has focused on level of functioning. These studies are difficult to interpret, however, because race and ethnicity are associated with a range of cognition-related factors. These potentially biasing influences are likely to be relatively stable over time, particularly in old age, suggesting that rate of change in cognition function over time is substantially less biased. In the past decade, several longitudinal studies have compared rates of cognitive decline in older Latino and non-Latino persons (Alley, Suthers, & Crimmins, 2007; Masel & Peek, 2009; Karlamangla et al., 2009; Early et al., 2013; Hildreth, Grigsby, Bryant, Wolfe, & Baxter, 2014). Two studies found no ethnic group differences in rates of cognitive decline (Karlamangla et al., 2009; Early et al., 2013). The other studies found no difference on some measures and more rapid decline in the Latino subgroup on other measures (Alley et al., 2007; Masel & Peek, 2009; Hildreth et al., 2014). The factors contributing to these mixed results are uncertain. Because with few exceptions (Early et al., 2013) previous studies have relied on brief of tests of global cognition, it may be that Latino ethnicity is related to decline in some cognitive functions but not others. It is also possible that ethnic differences in retest learning (Early et al., 2013), socioeconomic status (Zeki Al Hazzouri, Haan, Kalbfleisch et al., 2011; Zeki Al Hazzouri, Haan, Osypuk et al., 2011), or health (Collins, Sachs-Ericsson, Preacher, Sheffield, & Markides, 2009; Zeki Al Hazzouri et al., 2013) are confounding comparisons between ethnic groups.

The aim of the present analyses was to compare trajectories of change in cognitive abilities in older Latino and non-Latino individuals. Persons from 3 longitudinal cohort studies were eligible if they did not have dementia at enrollment. We used propensity matching to identify subgroups of Latino and non-Latinos balanced in age at baseline, education, race, and number of completed cognitive evaluations. A battery of 17 cognitive tests was administered annually for a mean of nearly 6 years and previously established composite measures of specific cognitive functions were derived. In a series of mixed-effects models, we tested for ethnic group differences in cognitive trajectories and assessed whether retest effects or selected covariates influenced ethnic group comparisons.

Method

Participants

Analyses are based on older individuals from 3 ongoing longitudinal cohort studies that each include annual administration of a battery of 18 cognitive performance tests. The Religious Orders Study began in 1994 (Wilson, Bienias, Evans, & Bennett, 2004; Bennett, Schneider, Arvanitakis, & Wilson, 2012). Its participants are Catholic priests, monks, and nuns from across the United States. Approximately 5% are Latino. The Rush Memory and Aging Project began in 1997 (Bennett, Schneider, Buchman, Mendes de Leon, & Wilson, 2005; Bennett, Schneider, Buchman, Barnes et al., 2012). Its participants are lay persons residing in the Chicago metropolitan area and approximately 4% are Latino. The Minority Aging Research Study began in 2004. Its participants are Black persons from the Chicago metropolitan area (Barnes, Shah, Aggarwal, Bennett, & Schneider, 2012; Arvanitakis, Bennett, Wilson & Barnes, 2010). Approximately 2% are Latino. Persons in each study provided written informed consent following a detailed discussion about the project. The institutional review board of Rush University Medical Center approved each study.

At the time of these analyses, 3,336 persons without dementia at baseline had completed at least one annual follow-up assessment: 129 were Latinos and 3,207 were non-Latinos. We formed groups of Latinos (n=104) and non-Latinos (n=104), balanced in age at baseline, education, race, and number of cognitive evaluations, using a greedy 5-to-1 digit algorithm in SAS for propensity score matching and subgroup identification (Rassen et al., 2012). Table 1 shows that this approach yielded groups similar in age, education, race, and number of annual cognitive assessments. The groups also had similar distributions of gender and baseline Mini-Mental Sate Examination scores. The 25 Latino participants for whom a match could not be found compared to the 104 matched Latino participants were younger at baseline (67.7 vs 75.0, t[127] = 5.6, p<0.001), less educated (6.8 vs 14.1, t[127] = 6.7, p<0.001), less likely to be African American (0.0% vs 15.4%, χ2 [1] = 4.4, p=0.036), but they had a similar percent of women (72.0 vs 77.9, χ2 [1] = 0.4, p = 0.532) and baseline score on the Mini-Mental State Examination (27.0 vs 27.7, t[126] = 0.9, p=0.385).

Table 1.

Descriptive data on Latino and non-Latino groups

| Characteristic | Latino group | Non-Latino group | Statistical comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline, years | 75.0(7.5) | 74.1(9.1) | t[206]=0.8, p=0.414 |

| Education, years | 14.1(5.1) | 14.7(3.6) | t[183.9]=0.9, p=0.370 |

| African American, % | 15.4 | 15.4 | χ2[1]=0.0, p=1.000 |

| Cognitive evaluations, number | 6.9(4.7) | 6.5(4.0) | t[206]=0.7, p=0.504 |

| Men, % | 22.1 | 23.1 | χ2[1]=0.0, p=0.868 |

| MMSE score at baseline | 27.7(2.1) | 27.8(2.1) | t[205]=0.5, p=0.618 |

| Diabetes, % | 38.5 | 25.0 | χ2[1]=4.4, p=0.037 |

| Hypertension, % | 77.9 | 70.2 | χ2[1]=1.6, p=0.206 |

| Smoking, % | 24.0 | 39.4 | χ2[1]=5.7, p=0.017 |

| Early life household SES | −0.41(0.91) | −0.05(0.71) | t[185.0]=3.1, p=0.016 |

| Mean depressive symptoms | 1.46(1.53) | 1.20(1.48) | t[204]=1.2, p=0.215 |

Note. Data are presented as mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise indicated. MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; SES, socioeconomic status.

Clinical Evaluation

At each annual visit, there was a structured medical history, neurologic examination, and cognitive function testing. Following the evaluation, a clinician diagnosed dementia based on a history of cognitive decline and impairment in two or more domains of cognition following the guidelines of the joint working group of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (McKhann et al., 1984). Persons were excluded from analyses if they met these criteria at baseline.

Cognitive Function Assessment

A battery of 18 cognitive tests was administered each year in an approximately 1-hour session. One test, the Mini-Mental State Examination, is a brief measure of global cognition. Based in part on previous factor analyses in Latino (Krueger, Wilson, Bennett, & Aggarwal, 2009) and predominantly non-Latino (Wilson et al., 2002; Wilson, Barnes, & Bennett, 2003; Wilson et al., 2005; Wilson et al., 2009) groups, we placed the remaining 17 individual tests into one of five cognitive domains, and we formed composite measures of each domain for use in longitudinal analyses to minimize floor and ceiling artifacts. Episodic memory was based on 7 tests: immediate and delayed recall of Logical Memory Story A (Wechsler, 1987) and the East Boston Story (Albert et al., 1991; Wilson et al., 2002) and Word List Memory, Word List Recall, and Word List Recognition (Welsh et al., 1994; Wilson et al., 2002). Semantic memory was based on a 15-item version (Welsh et al., 1994) of the Boston Naming Test (Kaplan, Goodglass, & Weintraub), a 15-item word reading test (Wilson et al., 2002), and a verbal fluency test involving naming animals and vegetables in 1-min trials (Welsh et al., 1994; Wilson et al., 2002). Working memory was based on Digit Span Forward, Digit Span Backward, and Digit Ordering (Wechsler, 1987; Wilson, 2002). Perceptual speed was assessed with modified versions (Wilson, 2002) of the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (Smith, 1982) and Number Comparison (Ekstrom, French, Harman, & Kermen, 1976). Visuospatial ability was based on a 9-item form (Wilson, 2002) of Standard Progressive Matrices (Raven, Court, & Raven, 1992) and a 15-item form of Judgment of Line Orientation (Benton, Sivan, Hamsher, Varney, & Spreen, 1994). We also formed a measure of global cognition based on all 17 tests. Each composite cognitive score was constructed by converting the raw scores of component tests to z scores, using the baseline mean and standard deviation of all individuals in the parent studies, and then computing the mean of the z scores of the component tests. Additional information on the individual tests and composite measures is published elsewhere (Wilson et al., 2002; Wilson, Barnes et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2005).

Statistical Analyses

To assess change in cognitive function over time and to test for ethnic differences in annual rate of change, we used linear mixed-effects models (Laird & Ware, 1982) with time treated as years since the baseline evaluation. Each model included terms for baseline age, sex, education, Latino ethnicity, and their interactions with time. Random effects for the intercept and slope were included to account for variability in initial level of cognition and rate of cognitive change. Subsequent analyses included terms for the interaction of Latino group × age and Latino group × age × time; excluded the only four Latino participants consistently tested in Spanish; used the Mini-Mental State Examination as the outcome; and added terms for selected covariates and their interactions with time. Model fit was assessed with pseudo-R-squared (Singer & Willett, 2003).

Retest learning was assessed using two modeling approaches (Wilson, Capuano, Sytsma, Bennett, & Barnes, 2015). First, to determine the existence and duration (in years) of the retest effect, we constructed a mixed-effects change point model that permitted the cognitive slope to shift. This model was fit with OpenBugs software (Lunn, Spiegelhatter, Thomas, & Best, 2009) using a Bayesian Monte Carlo Markov Chain approach (Gelman, Carli, Stern, & Rubin, 2004). The analytic model included parameters for the intercept at baseline, initial slope, change point, and slope after change point. We required the shift to take place during the first 6 years of observation to avoid capturing the terminal increase in cognitive decline often observed in the last years of life (Wilson, Beckett, Bienias, Evans, & Bennett, 2003; Sliwinski et al., 2006; Wilson, Segawa, Hizel, Boyle, & Bennett, 2011). The outcome for this change point model was a composite measure of global cognition. To assess retest learning in specific domains of cognition, we repeated the original linear mixed-effects models, first eliminating baseline data and then again eliminating data from baseline and the first follow-up because the change point analysis suggested that much of retest learning occurred in these initial visits.

Results

Annual Rate of Cognitive Decline

The primary analytic aim was to characterize rate of change in cognitive function and test whether ethnic group membership was associated with initial level of function or annual rate of cognitive decline (Table 2). To accomplish this aim, we used linear mixed-effects models adjusted for age at baseline, sex, and education. There was decline in each cognitive domain during the observation period, as indicated by the terms for time in Table 2. The groups did not differ in baseline level of cognitive function though there were nearly significant differences favoring the non-Latino group in working memory and perceptual speed. The ethnic groups did not differ in rate of decline in any domain, as indicated by the terms for group × time in Table 2.

Table 2.

Association of demographic variables with level of and change in different cognitive domains

| Model Term | Episodic Memory | Semantic Memory | Working Memory | Perceptual Speed | Visuospatial Ability | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | p | Estimate | SE | p | Estimate | SE | p | Estimate | SE | p | Estimate | SE | p | |

| Intercept | 0.141 | 0.062 | 0.024 | 0.099 | 0.075 | 0.190 | 0.041 | 0.073 | 0.577 | 0.081 | 0.091 | 0.376 | −0.039 | 0.074 | 0.598 |

| Time | −0.061 | 0.016 | <0.001 | −0.070 | 0.017 | <0.001 | −0.054 | 0.013 | <0.001 | −0.086 | 0.013 | <0.001 | −0.036 | 0.016 | 0.024 |

| Age at baseline | −0.028 | 0.005 | <0.001 | −0.026 | 0.006 | <0.001 | −0.009 | 0.006 | 0.145 | −0.046 | 0.007 | <0.001 | −0.010 | 0.006 | 0.099 |

| Male gender | −0.182 | 0.097 | 0.063 | 0.024 | 0.117 | 0.839 | 0.124 | 0.114 | 0.276 | −0.050 | 0.142 | 0.727 | 0.425 | 0.115 | <0.001 |

| Education | 0.053 | 0.009 | <0.001 | 0.065 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.071 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.064 | 0.014 | <0.001 | 0.044 | 0.011 | <0.001 |

| Latino group | 0.089 | 0.081 | 0.276 | −0.132 | 0.098 | 0.180 | −0.163 | 0.095 | 0.088 | −0.221 | 0.118 | 0.064 | −0.105 | 0.097 | 0.279 |

| Age × time | −0.008 | 0.001 | <0.001 | −0.007 | 0.001 | <0.001 | −0.005 | 0.001 | <0.001 | −0.006 | 0.001 | <0.001 | −0.005 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Gender × time | −0.021 | 0.023 | 0.358 | −0.022 | 0.024 | 0.372 | −0.019 | 0.018 | 0.293 | 0.007 | 0.019 | 0.701 | 0.032 | 0.023 | 0.155 |

| Education × time | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.630 | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.419 | −0.004 | 0.002 | 0.041 | −0.003 | 0.002 | 0.171 | −0.003 | 0.002 | 0.233 |

| Group × time | 0.015 | 0.020 | 0.459 | 0.018 | 0.021 | 0.395 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.640 | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.347 | −0.021 | 0.020 | 0.293 |

| Random effects | Variance | Variance | Variance | Variance | Variance | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.285 | 0.421 | 0.391 | 0.649 | 0.364 | ||||||||||

| Slope | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.008 | ||||||||||

| Error | 0.123 | 0.162 | 0.179 | 0.132 | 0.245 | ||||||||||

| Model Fit | Pseudo-R-squared | Pseudo-R-squared | Pseudo-R-squared | Pseudo-R-squared | Pseudo-R-squared | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.73 | |||||||||||

Note. From 5 separate mixed-effects models.

Table 2 also shows that there was an age × time interaction in each domain, indicating that rate of cognitive decline was more rapid in older participants compared to younger participants. To determine whether ethnicity was associated with this age related increase in cognitive decline, we repeated the initial models with terms added for the 2-way interaction of Latino group × age and the 3-way interaction of Latino group × age × time. None of these interactions was significant.

Most Latino participants opted for the English version of the cognitive tests on all (n=96) or some (n=4) occasions. Results were not substantially changed when the four individuals consistently tested in Spanish were eliminated.

Because previous research has mainly been based on the Mini-Mental State Examination (Hildreth et al., 2014) or the Telephone Inventory of Cognitive Status (Alley et al., 2007; Masel & Peek, 2009; Karlamangla et al., 2009), a modification of the Mini-Mental State Examination adapted for administration by telephone, we conducted an analysis of the Mini-Mental State Examination for comparison purposes. In this analysis, the Mini-Mental State Examination score declined a mean of 0.606-point per year (SE = 0.111, p < 0.001). The ethnic groups did not differ in baseline score level (estimate for Latino group = 0.045, SE = 0.263, p = 0.865) or in annual rate of change (estimate for Latino group × time = 0.221, SE = 0.139, p = 0.113).

Retest Learning

Repeated administration of cognitive tests results in improved performance (Wilson, Li, Bienias, & Bennnett, 2006; Yang, Reed, & Kuan, 2012). Therefore, ethnic differences in retest learning, which have been reported in some prior research (Schleicher, Van Iddekinge, Morgeson, & Campion, 2010; Van Iddekinge, Morgeson, Schleicher, & Campion, 2011; Early et al., 2013), could confound between group comparisons of cognitive aging. We investigated this possibility using two additional modeling approaches. First, because retest learning is maximal during initial exposures to the test (Bartels, Wegrzyn, Wiedl, Ackermann, & Ehrenreich, 2010), suggesting that linear models may not be optimal, we constructed a mixed-effects change point model that allowed cognitive functioning to improve for a variable time period before subsequently declining. To minimize error, this analysis was based on a measure of global cognition derived from all 17 cognitive tests. In all 208 participants at baseline, it had an approximately normal distribution (mean=0.012, SD=0.569, skewness = −0.2). As shown in Table 3, the global cognitive score improved at a mean rate of 0.334-unit per year for a mean of 0.425-year after which it declined at a mean rate of 0.079-unit per year. Latino ethnicity was not related to the duration or degree of retest learning, and there was no ethnic difference in cognitive decline subsequent to the inflection point.

Table 3.

Association of demographic variables with nonlinear change in global cognition

| Fixed effects | Estimate | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | ||

| Intercept | 0.019 | −0.085, 0.121 |

| Initial slope | 0.334 | 0.098, 0.631 |

| Change point | 0.425 | 0.275, 0.614 |

| Slope after change point | −0.079 | −0.109, −0.050 |

| Age at baseline | ||

| Intercept | −0.023 | −0.032, −0.016 |

| Initial slope | −0.008 | −0.025, 0.008 |

| Change point | 0.005 | −0.004, 0.015 |

| Slope after change point | −0.007 | −0.009, −0.005 |

| Male gender | ||

| Intercept | −0.005 | −0.164, 0.153 |

| Initial slope | −0.078 | −0.386, 0.239 |

| Change point | 0.033 | −0.160, 0.249 |

| Slope after change point | −0.004 | −0.047, 0.039 |

| Education | ||

| Intercept | 0.051 | 0.036, 0.066 |

| Initial slope | 0.019 | −0.011, 0.053 |

| Change point | −0.000 | −0.020, 0.024 |

| Slope after change point | −0.002 | −0.006, 0.002 |

| Latino group | ||

| Intercept | −0.067 | −0.200, 0.067 |

| Initial slope | −0.009 | −0.290, 0.272 |

| Change point | 0.016 | −0.163, 0.200 |

| Slope after change point | 0.016 | −0.022, 0.053 |

| Random effects | ||

| Intercept | 0.177 | 0.136, 0.226 |

| Initial slope | 0.140 | 0.094, 0.302 |

| Change point | 0.023 | 0.010, 0.046 |

| Slope after change point | 0.010 | 0.008, 0.014 |

| Error | 0.062 | 0.057, 0.067 |

Note. From a mixed-effects change point model.

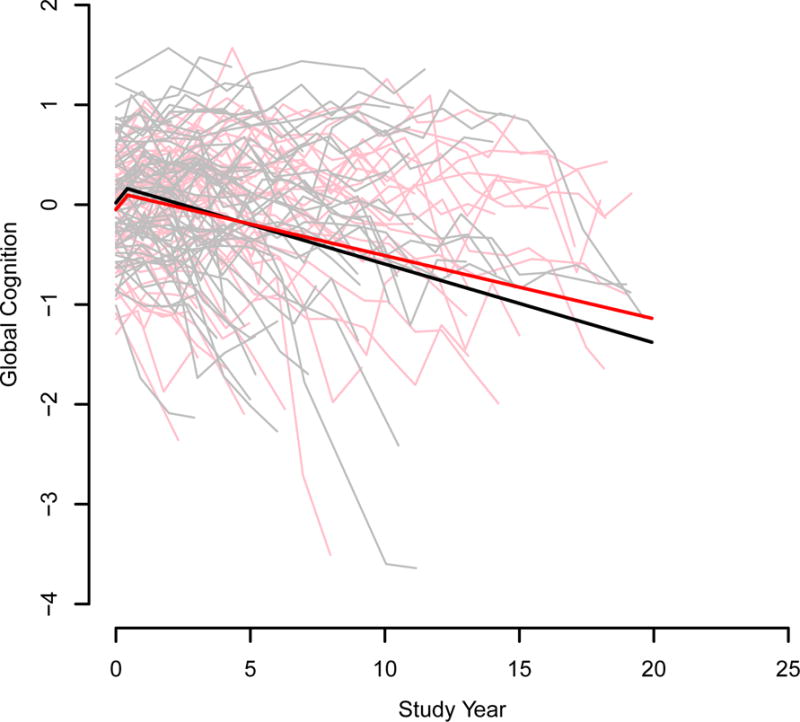

Plots of the crude paths of change in global cognition in all Latino (pink lines) and non-Latino (gray lines) participants suggest that change is not entirely linear (Figure 1). The mean paths predicted by the change point model for the Latino (red line) and non-Latino (black line) groups suggest similar patterns of retest learning.

Figure 1.

Crude paths of global cognitive change in all older Latino (pink lines) and non-Latino (gray lines) participants and the paths predicted for a typical Latino (red line) and non-Latino (black line) from a mixed-effects change point model adjusted for age at baseline, sex, and education.

Second, to assess retest effects within cognitive domains, we repeated the initial linear mixed-effects models first excluding data from the baseline evaluation and then excluding data from the first two evaluations because the change point analysis suggested that most of the retest learning occurred during these evaluations. As shown in Table 4, the annual rate of cognitive decline estimated from these analyses, as indicated by the terms for time, was more rapid than the estimates from the initial models, and the fit of these linear models, as indicated by the estimates of pseudo-R squared in Table 4, was slightly improved compared to the initial models (Table 2). With this evidence that retest learning was reduced, there continued to be no evidence of ethnic group differences in level of function or rate of decline in any cognitive domain.

Table 4.

Effect of excluding initial evaluations on ethnic differences in cognitive trajectories

| Cognitive outcome | Fixed effects | Pseudo-R-squared | Baseline excluded (n=184) | Pseudo-R-squared | Baseline, year 1 excluded (n=163) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | P | Estimate | SE | P | ||||

| Episodic memory | Time | −0.081 | 0.017 | <0.001 | −0.094 | 0.020 | <0.001 | ||

| Latino group | 0.048 | 0.095 | 0.617 | 0.069 | 0.114 | 0.549 | |||

| Group × time | 0.019 | 0.022 | 0.388 | 0.021 | 0.026 | 0.414 | |||

| 0.89 | 0.90 | ||||||||

| Semantic memory | Time | −0.084 | 0.020 | <0.001 | −0.101 | 0.023 | <0.001 | ||

| Latino group | −0.162 | 0.114 | 0.156 | −0.183 | 0.136 | 0.181 | |||

| Group × time | 0.019 | 0.025 | 0.438 | 0.019 | 0.030 | 0.527 | |||

| 0.87 | 0.90 | ||||||||

| Working memory | Time | −0.075 | 0.015 | <0.001 | −0.079 | 0.019 | <0.001 | ||

| Latino group | −0.207 | 0.108 | 0.056 | −0.220 | 0.134 | 0.103 | |||

| Group × time | 0.016 | 0.018 | 0.388 | 0.008 | 0.024 | 0.733 | |||

| 0.82 | 0.83 | ||||||||

| Perceptual speed | Time | −0.098 | 0.016 | <0.001 | −0.104 | 0.018 | <0.001 | ||

| Latino group | −0.239 | 0.134 | 0.075 | −0.337 | 0.150 | 0.026 | |||

| Group × time | 0.003 | 0.020 | 0.896 | 0.019 | 0.022 | 0.389 | |||

| 0.92 | 0.92 | ||||||||

| Visuospatial ability | Time | −0.046 | 0.019 | 0.016 | −0.042 | 0.022 | 0.054 | ||

| Latino group | −0.109 | 0.116 | 0.352 | −0.112 | 0.128 | 0.384 | |||

| Group × time | −0.015 | 0.024 | 0.516 | −0.017 | 0.027 | 0.528 | |||

| 0.75 | 0.75 | ||||||||

Note. From 10 separate mixed-effects models adjusted for age at baseline, sex, and education. AIC, Akaike information criterion.

Potential Confounders

We considered the possibility that other factors associated with late-life cognitive function might affect the ethnic group comparisons. Because diabetes, smoking, and early household socioeconomic status have been related to cognitive health in previous research (Collins, et al., 2009; Zeki Al Hazzouri, Haan, Kalbfleisch et al., 2011; Zeki Al Hazzouri et al., 2013) and were related to ethnic group membership in this study (Table 1), we repeated the initial analyses with terms for each covariate and its interaction with time. In separate sets of analyses for diabetes, smoking, and early life household socioeconomic status, there continued to be no ethnic group differences in level of function or rate of decline in any cognitive domain.

Discussion

We assessed different cognitive abilities at annual intervals for an average of almost 6 years in older Latino and non-Latino individuals. Latino ethnicity was not related to initial level of function or rate of decline in any cognitive domain suggesting that cognitive aging is similar in Latinos and non-Latinos.

Several previous studies have reported more rapid cognitive decline in older Latino individuals compared to non-Latino individuals (Alley et al., 2007; Masel & Peek, 2009; Hildreth et al., 2014). However, these findings were based on brief mental status tests (i.e., Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status [Alley et al., 2007; Masel & Peek, 2009; Karlamangla et al., 2009], Mini-Mental State Examination [Hildreth el al., 2014]) that are subject to floor and ceiling artifacts when used longitudinally and each study found no ethnic differences on other cognitive tests. In addition, one study had less than two years of follow-up (Hildreth et al., 2014) and the findings of Alley et al. (2007) were contradicted by subsequent analyses of the same cohort with more follow-up (Karlamangla et al., 2009). The lack of an association between Latino ethnicity and cognitive decline in the present analyses is consistent with Karlamangla et al (2009) and in conjunction with Early et al. (2013) adds to current knowledge by showing that aging profiles of Latinos and non-Latinos appear to be similar across diverse domains of cognitive functioning.

A challenge in longitudinal research on cognition is that test performance improves with repeated administration of the test and this retest learning effect is difficult to disentangle from actual change in underlying cognitive abilities, especially when follow-up intervals are uniform (Hoffman, Hofer, & Sliwinski, 2011) as in the present study. Ethnic group differences in retest learning could, therefore, confound comparisons of cognitive aging between ethnic groups. However, in the present analyses, Latino ethnicity was not related to the magnitude or duration of the retest effect and excluding data from evaluations most subject to retest learning did not substantially affect ethnic group comparisons. This is consistent with Karlamangla et al (2009). One previous study found more retest learning in Latinos compared to non-Latinos (Early et al., 2013), but this was only true for one of three outcomes. Therefore, the weight of the current evidence is that Latino ethnicity is probably not strongly associated with retest learning.

We considered the possibility that results might be affected by ethnic differences in cognition related aspects of health and well being, particularly vascular risk factors (Collins et al., 2009; Zeki Al Hazzouri et al., 2013) and indicators of socioeconomic status (Zeki Al Hazzouri et al., 2010; Zeki Al Hazzouri et al., 2011) that have previously been associated with cognition in older Latino individuals. Compared to the non-Latino group, the Latino group in these analyses had lower household socioeconomic status in childhood and was less likely to have smoked and more likely to currently have diabetes. However, controlling for these factors did not substantially affect between ethnic group comparisons.

Strengths and limitations of these data should be noted. The propensity matching enhanced the comparability of the groups on factors other than ethnicity. There was a mean of nearly 6 years of annual cognitive testing with psychometrically sound cognitive outcomes, allowing us to characterize person-specific paths of linear and nonlinear cognitive decline. Participation in follow-up was high; minimizing the likelihood that selective attrition substantially affected results. Participants were selected and so the generalizability of the findings will need to be established in future research. There were fewer Latino participants in this study than most previous studies. The resulting relative lack of statistical power probably contributed to the absence of a Latino disadvantage in level of performance on some cognitive measures. We probably also lacked the power to detect a small ethnic group difference in rate of cognitive decline, but the observed differences generally favored the Latino subgroup, making it unlikely that we failed to detect a Latino deficit. The Latino participants in these analyses are well educated compared to older Latinos living in the United States and so the findings may not generalize to less educated Latinos. Finally, we treated ethnicity as a unitary construct but our participants come or have ancestry from numerous countries throughout the Caribbean as well as Central and South America. This regional diversity, undoubtedly accompanied by cultural diversity, underscores the importance of understanding within ethnic group variability in late-life cognitive health in addition to between ethnic group differences.

In summary, these results suggest that trajectories of cognitive aging in Latinos and non-Latinos are broadly comparable. However, there was wide variability within the Latino group and the factors contributing to this variability have not been extensively investigated. Specifically, there have been few studies of potentially modifiable lifestyle and personality risk factors identified in groups of mostly non-Latino older persons. In addition, there have been few studies of biomarkers in Latinos and virtually no postmortem studies. The long term goal of the present program of research is to recruit and enroll older Latinos who agree to detailed annual clinical evaluations, collection of antemortem biologic specimens, and brain autopsy and neuropathologic examination at death to determine the pathologic and non-pathologic factors underlying cognitive aging in Latinos and thereby inform strategies to preserve and enhance late-life cognitive health in Latinos.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants (DAB: R01AG17917, P30AG10161), (LLB: R01AG022018) and the Illinois Department of Public Health. The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

The authors thank the participants of the Minority Aging Research Study, Rush Memory and Aging Project, and Religious Orders Study for their invaluable contributions; Charlene Gamboa, MPH, Tracy Colvin, MPH, Tracey Nowakowski, Barbara Eubler, and Karen Lowe Graham, MS, for study recruitment and coordination; John Gibbons, MS, and Greg Klein, MS, for data management; Alysha Kett, MS, for statistical programming; and the staff of the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Robert S. Wilson, Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Department of Neurological Sciences, Department of Behavioral Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL

Ana W. Capuano, Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Department of Neurological Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL

David X. Marquez, University of Illinois at Chicago, Department of Kinesiology and Nutrition, Chicago, IL

Priscilla Amofa, Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL.

Lisa L. Barnes, Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Department of Neurological Sciences, Department of Behavioral Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL.

David A. Bennett, Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Department of Neurological Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL

References

- Albert M, Smith LA, Scherr PA, Taylor JO, Evans DA, Funkenstein HH. Use of brief cognitive tests to identify individuals in the community with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;57:167–178. doi: 10.3109/00207459109150691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alley D, Suthers K, Crimmins E. Education and cognitive decline in older Americans: results from the AHEAD sample. Research on Aging. 2007;29:73–94. doi: 10.1177/0164027506294245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis Z, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Barnes LL. Diabetes and cognitive systems in older Black and White persons. Alzheimer’s Disease and Associated Disorders. 2010;24:37–42. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181a6bed5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes LL, Shah RC, Aggarwal NT, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. The Minority Aging Research Study: ongoing efforts to obtain brain donation in African Americans without dementia. Current Alzheimer’s Research. 2012;9:736–747. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels C, Wegrzyn M, Wiedl A, Ackermann V, Ehrenreich H. Practice effects in healthy adults: a longitudinal study on frequent repetitive cognitive testing. BMC Neuroscience. 2010;11:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Mendes de Leon CF, Wilson RS. The Rush Memory and Aging Project: study design and baseline characteristics of the study cohort. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:163–175. doi: 10.1159/000087446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the Religious Orders Study. Current Alzheimer Research. 2012;9:628–645. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Current Alzheimer Research. 2012;9:646–663. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Sivan AB, de Hamsher KS, Varney NR, Spreen O. Contributions to neuropsychological assessment. 2nd. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Collins N, Sachs-Ericsson N, Preacher KJ, Sheffield KM, Markides K. Smoking increases risk for cognitive decline among community-dwelling older Mexican Americans. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;17:934–942. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181b0f8df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early DR, Widaman KF, Harvey D, Beckett L, Park LQ, Farias ST, Mungas D. Demographic predictors of cognitive decline in ethnically diverse older persons. Psychology and Aging. 2013;28:633–645. doi: 10.1037/a0031645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom RB, French JW, Harman HH, Kermen D. Manual for kit of factor-referenced cognitive tests. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Gellman A, Carli JB, Stern HS, Rubin DB. Bayesian data analysis. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hildreth KL, Grigsby J, Bryant LL, Wolfe P, Baxter J. Cognitive decline and cardiometablic risk among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white adults in the San Luis Valley Health and Aging Study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;37:332–342. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L, Hofer SM, Silwinski MJ. On the confounds among retest gains and age-cohort differences in the estimation of within-person change in longitudinal studies: a simulation study. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26:778–791. doi: 10.1037/a0023910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan EF, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Karlamangla AS, Miller-Martinez D, Aneshensel CS, Seeman TE, Wight RG, Chodosh J. Trajectories of cognitive function in late life in the United States: demographic and socioeconomic predictors. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;170:331–342. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger KR, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Aggarwal NT. A battery of tests for assessing cognitive function in older Latino persons. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2009;23:384–388. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31819e0bfc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird N, Ware J. Random effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn D, Spiegelhalther D, Thomas A, Best N. The BUGS project: evolution, critique and future directions (with discussion) Statistics in Medicine. 2009;28:3049–3082. doi: 10.1002/sim.3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masel MC, Peek MK. Ethnic differences in cognitive function over time. Annals of Epidemiology. 2009;19:778–783. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services task Force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassen JA, Shelat AA, Myers J, Glynn RJ, Rothman KJ, Schneeweiss S. One-to-many propensity score matching in cohort studies. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2012;21:69–80. doi: 10.1002/pds.3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven JC, Court JH, Raven J. Manual for Raven’s progressive matrices and vocabulary: Standard Progressive Matrices. Oxford, England: Oxford Psychologists Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher DJ, Van Iddekinge CH, Morgeson FP, Campion MA. If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again: understanding race, age, and gender differences in retesting score improvement. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2010;95:603–617. doi: 10.1037/a0018920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski MJ, Stawski RS, Hall CB, Katz M, Verghese J, Lipton R. Distinguishing preterminal and terminal cognitive decline. European Psychologist. 2006;11:172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test manual-revised. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Van Iddekinge CH, Morgeson, Schleicher DJ, Campion MA. Can I retake it? Exploring subgroup differences and criterion-related validity in promotion retesting. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2011;96:941–955. doi: 10.1037/a0023562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh KA, Butters N, Mohs RC, Beekly D, Edland S, Fillenbaum G, Heyman A. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD), part V: a normative study of the neuropsychological battery. Neurology. 1994;44:609–614. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.4.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Aggarwal NT, Barnes LL, Bienias JL, Mendes de Leon CF, Evans DA. Biracial population study of mortality in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66:767–772. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Assessment of lifetime participation in cognitively stimulating activities. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2003;25:634–642. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.634.14572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Krueger KR, Hoganson G, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Early and late life cognitive activity and cognitive systems in old age. Journal of International Neuropsychological Society. 2005;11:400–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Beckett LA, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Bach J, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Individual differences in rates of change in cognitive abilities of older persons. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17:179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Beckett LA, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Terminal decline in cognitive function. Neurology. 2003;60:1782–1787. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000068019.60901.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Religious Orders Study: Overview and change in cognitive and motor speed. Aging Neuropsychology and Cognition. 2004;11:280–303. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Capuano AW, Sytsma J, Bennett DA, Barnes LL. Cognitive aging in older Black and White persons. Psychology and Aging. 2015;30:279–285. doi: 10.1037/pag0000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Li Y, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Cognitive decline in old age: separating retest effects from the effects of growing older. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:774–789. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.4.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Segawa E, Hizel LP, Boyle PA, Bennett DA. Terminal dedifferentiation of cognitive abilities. Neurology. 2012;78:1116–1122. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824f7ff2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Reed M, Kuan C. Retest learning in the absence of item-specific effects: does it show in the oldest-old? Psychology and Aging. 2012;27:701–706. doi: 10.1037/a0026719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeki Al Hazzouri A, Haan MN, Kalbfleisch JD, Galea S, Lisabeth LD, Aiello AE. Life-course socioeconomic position and incidence of dementia and cognitive decline in older Mexican Americans: results from the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;173:1148–1158. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeki Al Hazzouri A, Haan MN, Neuhaus JM, Pletcher M, Peralta CA, Lopez L, Stable EJP. Cardiovascular risk score, cognitive decline, and dementia in older Mexican Americans: the role of sex and education. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;2:e004978. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.004978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeki Al Hazzouri A, Haan MN, Osypuk T, Abdou C, Hinton L, Aiello AE. Neighborhood socioeconomic context and cognitive decline among older Mexican Americans: results from the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;174:423–431. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]