Abstract

Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene) extends the lifespan of diverse species including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster. In these organisms, lifespan extension is dependent on Sir2, a conserved deacetylase proposed to underlie the beneficial effects of caloric restriction. Here we show that resveratrol shifts the physiology of middle-aged mice on a high-calorie diet towards that of mice on a standard diet and significantly increases their survival. Resveratrol produces changes associated with longer lifespan, including increased insulin sensitivity, reduced insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-I) levels, increased AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor- γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) activity, increased mitochondrial number, and improved motor function. Parametric analysis of gene set enrichment revealed that resveratrol opposed the effects of the high-calorie diet in 144 out of 153 significantly altered pathways. These data show that improving general health in mammals using small molecules is an attainable goal, and point to new approaches for treating obesity-related disorders and diseases of ageing.

The number of overweight individuals worldwide has reached 2.1 billion, leading to an explosion of obesity-related health problems associated with increased morbidity and mortality1,2. Although the association of obesity with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes is well known, it is often under-appreciated that the risks of other age-related diseases, such as cancer and inflammatory disorders, are also increased. At the other end of the spectrum, reducing caloric intake by ~40% below that of ad libitum-fed animals (caloric restriction) is the most robust and reproducible way to delay age-related diseases and extend lifespan in mammals3,4.

Experiments with Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Drosophila melanogaster have implicated the sirtuin/Sir2 family of NAD+-dependent deacetylases and mono-ADP-ribosyltransferases as mediators of the physiological effects of caloric restriction5. In mammals, seven sirtuin genes have been identified (SIRT1–7). SIRT1 regulates such processes as glucose and insulin production, fat metabolism, and cell survival, leading to speculation that sirtuins might mediate effects of caloric restriction in mammals5. We previously screened over 20,000 molecules to identify ~25 that enhance SIRT1 activity in vitro6. Resveratrol, a molecule produced by a variety of plants in response to stress, emerged as the most potent.

Resveratrol has since been shown to extend the lifespan of evolutionarily distant species including S. cerevisiae, C. elegans and D. melanogaster in a Sir2-dependent manner6–9. A recent study found that resveratrol improves health and extends maximum lifespan by 59% in a vertebrate fish10. In mammalian cells, resveratrol produces SIRT1-dependent effects that are consistent with improved cellular function and organismal health11–15. Whether resveratrol acts directly or indirectly through Sir2 in vivo is currently a subject of debate16.

On the basis of the unprecedented ability of resveratrol to improve health and extend lifespan in simple organisms, we have asked whether it has similar effects in mice. We hypothesized that resveratrol might shift the physiology of mice on a high-calorie diet towards that of mice on a standard diet and provide the associated health benefits without the mice having to reduce calorie intake. Cohorts of middle-aged (one-year-old) male C57BL/6NIA mice were provided with either a standard diet (SD) or an otherwise equivalent high-calorie diet (60% of calories from fat, HC) for the remainder of their lives. To each of the diets, we added resveratrol at two concentrations that provided an average of 5.2 ± 0.1 and 22.4 ± 0.4 mg kg−1 day−1, which are feasible daily doses for humans. After 6 months of treatment, there was a clear trend towards increased survival and insulin sensitivity. Because the effects were more prominent in the higher dose (22.4 ± 0.4 mg kg−1 day−1, HCR), we initially focused our resources on this group and present the results of those analyses herein. Analyses of the other groups will be presented at a later date.

Increased survival

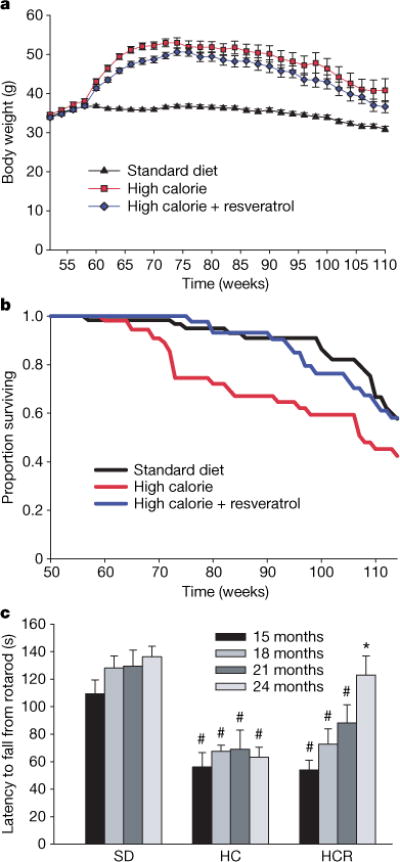

Mice on the HC diet steadily gained weight until ~75 weeks of age, after which average weight slowly declined (Fig. 1a). Although mice on the HCR diet were slightly lighter than the HC mice during the initial months, there was no significant weight difference between the groups from 18–24 months, when most of our analyses were performed. There was also no difference in body temperature (Table 1), food consumption (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b), total faecal output or lipid content (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d), or post-mortem body fat distribution (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Resveratrol increases survival and improves rotarod performance.

a, Body weights of mice fed a standard diet (SD), high-calorie diet (HC), or high-calorie diet plus resveratrol (HCR). b, Kaplan–Meier survival curves. Hazard ratio for HCR is 0.69 (χ2 = 5.39, P = 0.020) versus HC, and 1.03 (χ2 = 0.022, P = 0.88) versus SD. The hazard ratio for HC versus SD is 1.43 (χ2 = 5.75, P = 0.016). c, Time to fall from an accelerating rotarod was measured every 3 months for all survivors from a pre-designated subset of each group; n = 15 (SD), 6 (HC) and 9 (HCR). Asterisk, P < 0.05 versus HC; hash, P < 0.05 versus SD. Error bars indicate s.e.m.

Table 1.

Effects of a high-fat diet and resveratrol on various biomarkers in plasma

| Parameter | Standard diet | High calorie | High calorie 1 resveratrol | Fed or Fasted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free fatty acids (mequiv.) | 0.27 (0.04) | 0.59 (0.06)† | 0.53 (0.03)† | Fed |

| 0.83 (0.10) | 0.45 (0.20) | 0.54 (0.05) | Fasted | |

| Triglycerides (mg dl−1) | 76.6 (6.8) | 81.4 (6.6) | 88.2 (10.8) | Fasted |

| Cholesterol (mg dl−1) | 135 (7) | 183 (20)† | 204 (16)† | Fasted |

| Insulin (ng ml−1) | 1.77 (0.64) | 9.21 (1.95)† | 2.46 (0.47)* | Fed |

| 0.73 (0.14) | 2.70 (0.36)† | 1.06 (0.30)* | Fasted | |

| Glucose (mg dl−1) | 129.0 (5.4) | 118.3 (4.7) | 114.8 (6.3) | Fed |

| 94.5 (3.3) | 125.3 (11.6)† | 85.6 (10.3)* | Fasted | |

| IGF-I (ng ml−1) | 346 (40) | 534 (12)† | 482 (21)†‡ | Fed |

| 625 (33) | 999 (102)† | 929 (81)† | Fasted | |

| IGFBP-1 (AU) | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.7 (0.3) | 1.7 (1.0) | Fed |

| 1.0 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.1)† | Fasted | |

| IGFBP-2 (AU) | 1.0 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.04) | 0.9 (0.1) | Fasted |

| Leptin (ng ml−1) | 2.0 (1.1) | 21.6 (7.2) | 11.6 (6.5) | Fasted |

| Adiponectin (μg ml−1) | 12.1 (1.6) | 9.5 (0.5) | 9.0 (0.8) | Fed |

| Amylase (Ul−1) | 2,060 (150) | 2,960 (320)† | 2,190 (230)* | Fasted |

| Ala aminotransferase (U l−1) | 347 (119) | 390 (61) | 446 (88) | Fasted |

| Asp aminotransferase (U l−1) | 448 (85) | 425 (90) | 512 (46) | Fasted |

| Creatine phosphokinase (U l−1) | 4,260 (1820) | 2,010 (810) | 2,520 (680) | Fasted |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U l−1) | 1,530 (240) | 1,610 (170) | 2,020 (180) | Fasted |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U l−1) | 43.8 (3.4) | 44.6 (6.0) | 34.2 (1.4) | Fasted |

| Bilirubin (mg dl−1) | 0.16 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.03) | 0.16 (0.02) | Fasted |

| Albumin (g dl−1) | 2.78 (0.16) | 2.88 (0.19) | 2.66 (0.14) | Fasted |

| Creatinine (mg dl−1) | 0.54 (0.02) | 0.48 (0.04) | 0.46 (0.04) | Fasted |

| Cyclo-oxygenase (liver, AU mg−1) | 1.00 (0.14) | 0.80 (0.11) | 0.83 (0.11) | Fed |

| Citrate synthase (liver, AU mg−1) | 141 (14) | 128 (21) | 138 (11) | Fed |

| Body temperature (°C) | 34.71 (0.14) | 35.52 (0.17)† | 35.57 (0.15)† | Fed |

Values shown are mean (±s.e.m.). AU, arbitrary units; U l−1, units per litre.

P < 0.05 versus high calorie.

P < 0.05 versus standard diet.

P < 0.05 versus high calorie by one-tailed Student’s t-test.

At 60 weeks of age, the survival curves of the HC and HCR groups began to diverge and have remained separated by a 3–4-month interval (Fig. 1b). A similar effect on survival was observed in a previous study of one-year-old C57BL/6 mice on caloric restriction, ultimately resulting in a 20% extension of mean lifespan17. With the present age of the colony at 114 weeks, 58% of the HC control animals have died (median lifespan 108 weeks), as compared to 42% of the HCR group and 42% of the SD controls. Although we cannot yet confidently predict the ultimate mean lifespan extension, Cox proportional hazards regression shows that resveratrol reduced the risk of death from the HC diet by 31% (hazard ratio = 0.69, P = 0.020), to a point where it was not significantly different from the SD group (hazard ratio = 1.03, P = 0.88).

Although resveratrol increased survival, it was important to ascertain whether quality of life was maintained. One way to assess this was to measure balance and motor coordination, which we did by examining the ability to perform on a rotarod. Surprisingly, the resveratrol-fed HC mice steadily improved their motor skills as they aged, to the point where they were indistinguishable from the SD group (Fig. 1c). It is possible that the improved rotarod performance might have been due to minor differences in body weight but we view this as unlikely because we found no correlation between body weight and performance within groups and rotarod performance was also improved for resveratrol-treated SD mice (R.deC. and K.P., unpublished data). These data are reminiscent of the resveratrol-mediated increase in motor activity in older individuals of the vertebrate fish species Nothobranchius furzeri10.

Increased insulin sensitivity

In humans, high-calorie diets cause numerous pathological conditions including increased glucose and insulin levels leading to diabetes, cardiovascular disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, a condition for which there is no effective treatment18. The HC-fed mice had alterations in plasma levels of markers that predict the onset of diabetes and a shorter lifespan, including increased levels of insulin, glucose and IGF-1 (Table 1). The HCR group had significantly lower levels of these markers, paralleling the SD group. An oral glucose tolerance test indicated that the insulin sensitivity of the resveratrol-treated mice was considerably higher than controls (Fig. 2a–d). Homeostatic model assessment, which is used to quantify insulin resistance, gave scores of 2.5 for SD, 8.8 for HC and 3.5 for HCR, confirming improved sensitivity (HCR versus HC, P = 0.01). Although the persistence of high glucose levels for more than 60 min following an oral dose is unusual for young mice, it is typical for older animals19. Compared to the HC controls, the areas under the curves for both glucose and insulin levels were significantly decreased in the resveratrol-fed HC group and were not significantly different from mice in the SD group (Fig. 2b, d).

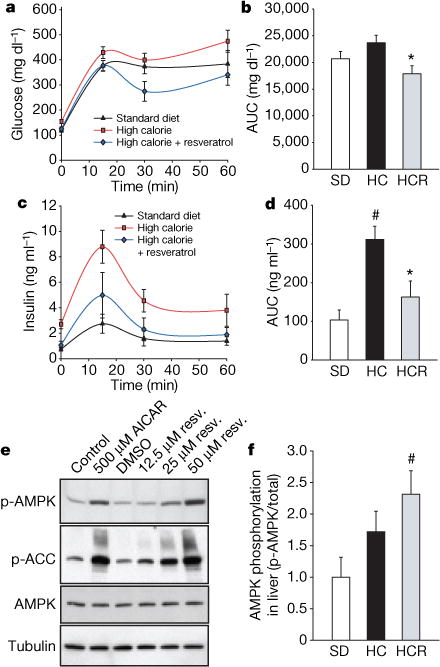

Figure 2. Resveratrol improves insulin sensitivity and activates AMPK.

a–d, Plasma levels of glucose (a, b) and insulin (c, d) were measured after a 2 g kg−1 oral glucose dose. Areas under the curves (AUC) were significantly reduced by resveratrol treatment. e, Activation of AMPK by resveratrol in CHO cells. In the presence of resveratrol or 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR) as a positive control, phosphorylation of AMPK and its downstream target, acetyl-coA carboxylase (ACC), are increased. f, AMPK activity in liver. Phosphorylation of AMPK (f), acetyl-coA carboxylase (Supplementary Fig. 3e) and decreased expression of fatty acid synthase (Supplementary Fig. 3f) are indicative of enhanced AMPK activity. Asterisk, P < 0.05 versus HC; hash, P <0.05 versus SD. n = 5 for all groups. Error bars indicate s.e.m.

Next, we investigated possible mechanisms behind these metabolic effects. AMPK is a metabolic regulator that promotes insulin sensitivity and fatty acid oxidation. Its activity correlates tightly with phosphorylation at Thr 172 (p-AMPK). Chronic activation of AMPK occurs on a calorically restriction diet and has been proposed as a longevity strategy for mammals20. Consistent with this idea, additional copies of the AMPK gene are sufficient to extend lifespan in C. elegans21. Because we and others22 have observed that resveratrol can activate AMPK in cultured cells through an indirect mechanism (Fig. 2e; see also Supplementary 3a–d), we examined whether AMPK activation occurred in the livers of the resveratrol-fed group. Resveratrol showed a strong tendency towards inducing phosphorylation of AMPK (Fig. 2f), as well as two downstream indicators of activity, namely phosphorylation of acetyl-coA carboxylase at Ser 79 and decreased expression of fatty acid synthase (Supplementary Fig. 3e, f).

Decreased organ pathology

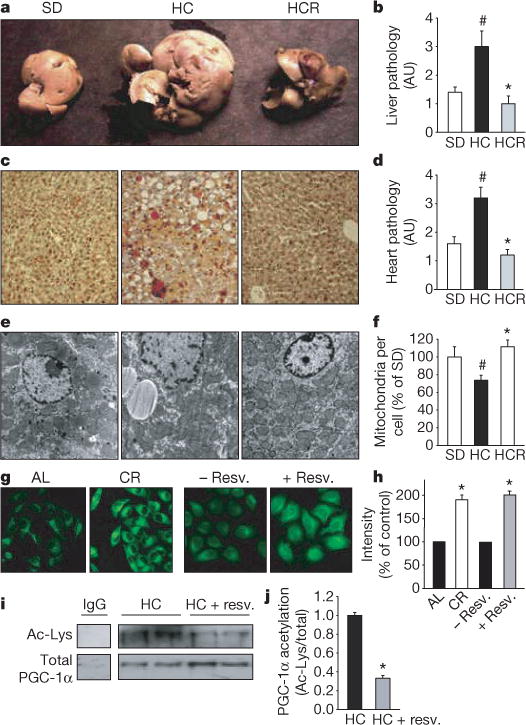

At 18 months of age it was apparent that the high-calorie diet greatly increased the size and weight of livers and that resveratrol prevented these changes (Fig. 3a–c; see also Supplementary Fig. 4a, b) without altering plasma lipid levels (Table 1). Histological examination of liver sections by staining with haematoxylin and eosin or oil red O revealed a loss of cellular integrity and the accumulation of large lipid droplets in the livers of the HC but not the HCR group. Blinded scoring of the liver sections for overall pathology on a scale of 0–4 (with 4 being the most severe) gave mean values of 1.3 for the SD group, 2.8 for the HC group and 0.8 for the HCR group (Fig. 3b). Plasma amylase, which can indicate pancreatic damage, was elevated in the HC group and was significantly reduced by resveratrol (Table 1). The reasons for the elevation of plasma amylase levels in the HC group are unclear given that pancreatic sections of all animals revealed no damage to the pancreas or decrease in islet area (data not shown). Differences in the weights of other organs did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 3. Resveratrol improves liver histology, increases mitochondrial number and decreases acetylation of PGC-1α.

a–c, Resveratrol prevents the development of fatty liver, as assessed by organ size (a), overall pathology (b) and decreased fat accumulation as measured by oil red O staining (c). AU, arbitrary units. d, Pathology of heart sections. Additional histology of liver, heart and aorta is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. e, f, Transmission electron microscopy of liver sections (e) and mitochondrial counts (f). g, h, Mitochondrial number in HeLa cells treated with serum from ad libitum-fed (AL) or calorically restricted (CR) rats, or resveratrol, and stained with Mitotracker green FM. i, j, Resveratrol reduces the acetylation of PGC-1α, a known SIRT1 target and regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, in vivo. PGC-1α was immunoprecipitated from liver extracts then blotted for acetyl lysine (i) and quantified (j). Asterisk, P < 0.05 versus HC; hash, P < 0.05 versus SD. n = 5 for b and d; n = 3 for f and j. Error bars indicate s.e.m.

The ability of resveratrol to improve motor function and increase insulin sensitivity indicated that its effects were not confined to the liver. To test directly whether other organs also benefited, we examined heart tissue of the SD, HC and HCR mice. Blinded scoring of overall pathology—taking into account subtle changes in the abundance of fatty lesions, cardiac muscle vacuolization, degeneration and inflammation—on a relative scale of 0–4 (with 4 being the most severe) gave mean values of 1.6 for the SD group, 3.2 for the HC group and 1.2 for HCR group (Fig. 3d; see also Supplementary Fig. 4c). Improvements in the morphology of the aortic elastic lamina were also apparent (Supplementary Fig. 4d).

Increased mitochondria

Exercise and reduced caloric intake increase hepatic mitochondrial number23,24 and we wondered whether resveratrol might produce the same effect. The livers of the resveratrol-treated mice had considerably more mitochondria than those of HC controls and were not significantly different compared to those of the SD group (Fig. 3e, f). There was also a trend towards higher citrate synthase activity in the resveratrol-fed mice (an indicator of increased mitochondrial content) although the effect was not significant (Table 1). Culturing FaO hepatoma or HeLa cells in the presence of resveratrol increased mitochondrial number (Fig. 3g, h), similar to the previously reported effect of culturing cells in serum from calorically restricted rats24.

Mitochondrial biogenesis in liver and muscle is controlled, in large part, by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1α25,26, the activity of which, in turn, is positively regulated by SIRT1-mediated deacetylation27,28. Hence, the acetylation status of PGC-1α is considered a marker of SIRT1 activity in vivo27. Because this assay required more tissue than was available, we examined a separate cohort of one-year-old mice on the HC diet that had been treated with resveratrol for 6 weeks at 186 mg kg−1 d−1. The acetylation status of PGC-1α in the resveratrol-fed mice was threefold lower than the diet-matched controls (Fig. 3i, j). There was no detectable increase in SIRT1 protein levels in resveratrol-treated mice (data not shown), suggesting that SIRT1 enzymatic activity was enhanced by resveratrol.

Microarrays and pathway analysis

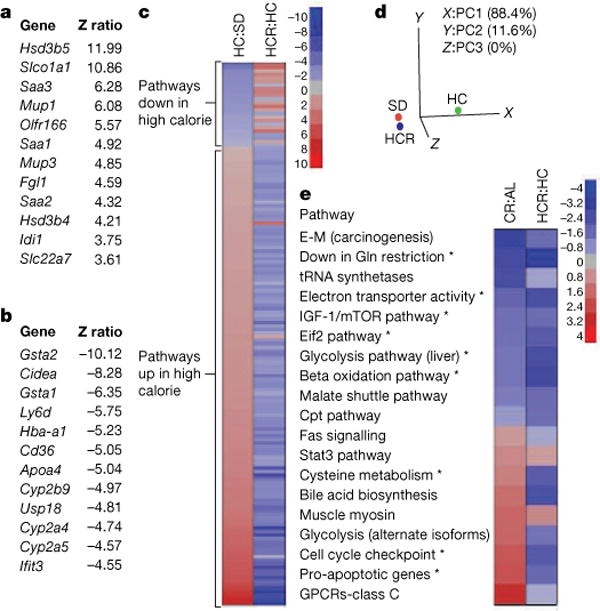

These data demonstrate that resveratrol can alleviate the negative impact of a high-calorie diet on overall health and lifespan. To determine to what extent resveratrol had shifted the physiology of the high-calorie group towards the lower calorie group, we performed whole-genome microarrays and pathway analysis on liver samples. Z ratios were calculated as described previously29 and a subset of expression changes was verified by polymerase chain reaction with reverse transcription (RT–PCR) (Supplementary Fig. 5). In the HCR group, expression patterns for 782 out of 41,534 (<2%) individual genes changed significantly relative to the diet-matched controls (Fig. 4a, b). Notably, within the top 12 most highly elevated transcripts were serum amyloid proteins (Saa1–3), major urinary proteins (Mup1 and Mup3), and both forms of hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase that degrade testosterone (Hsd3b4, Hsd3b5). The list of 12 most highly downregulated transcripts included three cytochrome p450 enzymes (Cyp2a4, Cyp2a5 and Cyp2b9) that are known to activate pro-carcinogens30. The complete data set is available at http://www.grc.nia.nih.gov/branches/rrb/dna/index/dnapubs.htm#2.

Figure 4. Resveratrol shifts expression patterns of mice on a high-calorie diet towards those on a standard diet.

a, b, The most highly significant upregulated (a) and downregulated (b) genes in livers of HC and HCR groups are shown. c, Parametric analysis of gene-set enrichment (PAGE) comparing every pathway significantly upregulated (red) or downregulated (blue) by either the HC diet or resveratrol (153 in total, with 144 showing opposing effects). d, Principal component analysis of PAGE data. The first principal component (PC1) is dominant, with 88.4% variability, and shows HCR to be more similar to SD than HC. e, Comparison of pathways significantly altered by resveratrol treatment and caloric restriction using data from the AGEMAP caloric restriction study. Pathways with significant differences between HC and HCR are indicated by an asterisk. Complete pathway listings are in Supplementary Fig. 7. Asterisk, P < 0.05 versus HC. n = 5 for SD and HC; n = 4 for HCR.

We next performed parametric analysis of gene set enrichment (PAGE), a computational method that determines differences between pathways using a priori defined gene sets31,32. PAGE analysis indicated that resveratrol caused a significant alteration in 127 pathways, including the TCA cycle, glycolysis, the classic and alternative complement pathways, butanoate and propanoate metabolism, sterol biosynthesis and Stat3 signalling (Supplementary Fig. 6; for a complete list see Supplementary Fig. 7). Some of the most highly downregulated pathways in the resveratrol-fed group are known to extend lifespan in model organisms when attenuated, including insulin signalling, IGF-1 and mTOR signalling, oxidative phosphorylation and electron transport33–36. Downregulation of glycolysis is a well known marker of caloric restriction37 and has been proposed as a mechanism by which caloric restriction works38. The increase in Stat3, a transcription factor involved in cell survival and liver regeneration39, is of note because its activity is known to be suppressed in the liver by high caloric diets and shows an age-related decline in activity that is attenuated by caloric restriction40,41.

A few of the pathway changes were unanticipated. Although we had observed an increase in mitochondrial number in the HCR group, there was a decrease in the transcription of numerous mitochondrial genes, suggesting that the turnover of mitochondrial proteins was reduced. This result was unexpected, but is consistent with a previous report showing that SIRT1-dependent activation of PGC-1α does not enhance transcription of mitochondrial genes27. Upregulation of complement, which occurs in obese and aged mice, was also observed in the HCR group for reasons that are currently unclear.

It is notable that resveratrol opposed the effects of high caloric intake in 144 out of 153 significantly altered pathways (Fig. 4c). In fact, the PAGE signature of the HCR group was considerably more similar to that of the SD group than the HC controls. Principal component analysis yielded values of −1.82 (SD), −1.41 (HCR) and 3.22 (HC), with 88.4% of the variability assigned to the first principal component, making the HC group the clear outlier (Fig. 4d).

We next compared our PAGE results to a pre-existing caloric restriction data set for C57BL/6 mice known as AGEMAP, hypothesizing that the comparison of changes induced by these two paradigms might reveal pathways common to the enhancement of health and longevity. Of the 36 different pathways identified by AGEMAP as being significantly altered by caloric restriction, there was sufficient overlap to compare 19 of them to our data (Fig. 4e). Pathways altered in the same direction by caloric restriction and resveratrol included the downregulation of IGF-1 and mTOR signalling, downregulation of glycolysis, and upregulation of Stat3 signalling. One interesting difference was that cell cycle checkpoint and apoptotic pathways were elevated in the caloric restriction group but downregulated by resveratrol. We do not favour the interpretation that the resveratrol-treated livers were undergoing less apoptosis because levels of AST and ALT, two indicators of hepatic apoptosis, were unchanged (see Table 1). Perhaps the downregulation of cell cycle checkpoints is linked to the recent discovery that inhibition of checkpoint function in C. elegans increases stress resistance and lifespan42. Although the statistical power of this analysis is limited by the overlap in data sets, the results suggest that more comprehensive comparisons of the effects of resveratrol and caloric restriction are warranted.

Discussion

The ability of resveratrol to prevent the deleterious effects of excess caloric intake and modulate known longevity pathways suggests that resveratrol and molecules with similar properties might be valuable tools in the search for key regulators of energy balance, health and longevity. As a case in point, the most highly upregulated gene in the HC group and second most highly downregulated gene in the HCR group was Cidea, which regulates energy balance in brown fat and provides resistance to obesity and diabetes when knocked out43.

Taken together, the findings in this study show that resveratrol shifts the physiology of mice consuming excess calories towards that of mice on a standard diet, modulates known longevity pathways, and improves health, as indicated by a variety of measures including survival, motor function, insulin sensitivity, organ pathology, PGC-1α activity, and mitochondrial number. Notably, all these changes occurred without a significant reduction in body weight. Whether these effects are due to resveratrol working primarily through SIRT1, which is the case for simpler metazoans, or through a combination of interactions, as predicted by the xenohormesis hypothesis6,44, remains to be determined. In either case, this study shows that an orally available small molecule at doses achievable in humans can safely reduce many of the negative consequences of excess caloric intake, with an overall improvement in health and survival.

METHODS

Animals and diets

Animal housing and diets are described in Supplementary Information. Briefly, one-year-old male C57BL/6NIA mice were maintained on AIN-93G standard diet (SD), AIN-93G modified to provide 60% of calories from fat (HC), or HC diet with the addition of 0.04% resveratrol (HCR).

Electron microscopy

Tissues were processed as previously reported, imaged at ×1,500 on a Jeol 1210 transmission microscope, and photographed using a Gatan US 4000 MP Digital camera. Mitochondria per cell and hepatocyte size were quantified using grid counting by three blinded raters.

PAGE analysis

RNA extracted from the livers of five 18-month-old mice per group was hybridized to Agilent 44k whole-genome microarrays following protocols listed on the Gene Expression and Genomics Unit website at the National Institute on Aging (http://www.grc.nia.nih.gov/branches/rrb/dna/index/protocols.htm). One array from the HCR group was discarded owing to RNA degradation. Raw data were subjected to Z normalization and tested for significant changes as previously described29. For parametric analysis of gene set enrichment (PAGE), a complete set of 522 pathways in the cell was obtained from http://www.broad.mit.edu/gsea/msigdb/msigdb_index.html. Details of the method are described in Supplementary Information and elsewhere31. Principal component analysis was performed on the replicate average for the three groups. These tools are part of DIANE 1.0, a program developed by V.V.P and available at http://www.grc.nia.nih.gov/branches/rrb/dna/diane_software.pdf. Caloric restriction data were extracted from the AGEMAP project.

Cell-based mitochondrial assays

Mitochondrial mass was determined using the mitochondria-specific fluorescent dye Mitotracker green FM after fixation of cells, with minor modifications. Staining after fixation permits determination of the incorporation of the dye due to mitochondrial mass independently of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm).

Serum markers and hormones

Details of biochemical assays are described in Supplementary Information.

AMPK and PGC-1α analysis

Extraction of tissues and cells for western blotting were performed using standard techniques. Details and antibodies are outlined in Supplementary Information.

Histology

Eighteen-month-old mice were fasted overnight and fixed using Streck fixative (Streck). Organs were sectioned and stained with haematoxylin and eosin or frozen and stained with oil red O lipid stain, then scored blindly for overall pathology.

Rotarod

Results shown are the average of three trials per mouse, measuring time to fall from an accelerating rotarod (4–40 r.p.m. over 5 min). Data from animals that survived to 24 months are shown.

Statistical analyses

Single factor analysis of variance followed by Fisher’s post-hoc tests were used for all comparisons, except where noted. Details are provided in Supplementary Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Rasnow for his donation towards purchasing the mice; V. Massari for help with electron microscopy; W. Matson for HPLC assays of resveratrol; M. Chachich and M. Tatar for help with statistical analysis; W. Wood for microarray assistance; D. Phillips for animal care; J. Egan’s group for insulin measurements; the Sinclair laboratory, N. Wolf, P. Elliott, C. Westphal, R. Weindruch, P. Lambert, J. Milne and M. Milburn for advice on experimental design; and S. Luikenhuis and M. Dipp for critical reading of the manuscript. D.A.S. was supported by The Ellison Medical Research Foundation, J.A.B. by The American Heart Foundation, H.J. and D.LeC. by an Australian NHMRC project grant and an NHMRC post-graduate scholarship, and C.L. and P.P. by the American Diabetes Association and NIH. This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIA, a Spanish MCyT grant to P.N., NIH grants to D.A.S., and by the support of P. F. Glenn and The Paul F. Glenn Laboratories for the Biological Mechanisms of Aging.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions All experiments were designed and carried out by J.A.B., K.J.P., R.deC. and D.A.S. with the exceptions noted below. D.K.I. assisted with the design and interpretation of experiments. N.L.P., A.K., J.S.A., K.L. and P.J.P. assisted with the handling of animals and behavioural studies. Electron microscopy was performed by H.A.J. and D.LeC. Computational methods for analysis of microarray data were developed and applied by V.V.P. and K.G.B. Analysis of PGC-1α acetylation was performed by C.L. and P.P. Pathological assessments were made by S.P. (livers), M.W. and E.G.L. (hearts and aortas). In vitro AMPK reactions were performed by D.G. and R.J.S. Citrate synthase activity was measured by O.B. Cell-based mitochondrial assays were performed by G.L.L. and P.N. MRI images were obtained by S.R., K.W.F. and R.G.S.

The authors declare competing financial interests: details accompany the paper on www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Olshansky SJ. Projecting the future of U.S. health and longevity. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(suppl 2):W5R86–W5R89. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.r86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Z, Bowerman S, Heber D. Health ramifications of the obesity epidemic. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:681–701. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingram DK, et al. Development of calorie restriction mimetics as a prolongevity strategy. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1019:412–423. doi: 10.1196/annals.1297.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinclair DA. Toward a unified theory of caloric restriction and longevity regulation. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:987–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guarente L, Picard F. Calorie restriction—the SIR2 connection. Cell. 2005;120:473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howitz KT, et al. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature. 2003;425:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature01960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood JG, et al. Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans. Nature. 2004;430:686–689. doi: 10.1038/nature02789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viswanathan M, Kim SK, Berdichevsky A, Guarente L. A role for SIR-2.1 regulation of ER stress response genes in determining C. elegans life span. Dev Cell. 2005;9:605–615. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarolim S, et al. A novel assay for replicative lifespan in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2004;5:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.femsyr.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valenzano DR, et al. Resveratrol prolongs lifespan and retards the onset of age-related markers in a short-lived vertebrate. Curr Biol. 2006;16:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Picard F, et al. Sirt1 promotes fat mobilization in white adipocytes by repressing PPAR-γ. Nature. 2004;429:771–776. doi: 10.1038/nature02583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, et al. SIRT1 protects against microglia-dependent amyloid-β toxicity through inhibiting NF-κB signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40364–40374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolthur-Seetharam U, Dantzer F, McBurney MW, de Murcia G, Sassone-Corsi P. Control of AIF-mediated cell death by the functional interplay of SIRT1 and PARP-1 in response to DNA damage. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:873–877. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.8.2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raval AP, Dave KR, Perez-Pinzon MA. Resveratrol mimics ischemic preconditioning in the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1141–1147. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frescas D, Valenti L, Accili D. Nuclear trapping of the forkhead transcription factor FoxO1 via Sirt-dependent deacetylation promotes expression of glucogenetic genes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20589–20595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denu JM. The Sir2 family of protein deacetylases. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weindruch R, Walford RL. Dietary restriction in mice beginning at 1 year of age: effect on life-span and spontaneous cancer incidence. Science. 1982;215:1415–1418. doi: 10.1126/science.7063854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siebler J, Galle PR. Treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2161–2167. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i14.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scrocchi LA, Drucker DJ. Effects of aging and a high fat diet on body weight and glucose tolerance in glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor–/– mice. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3127–3132. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.7.6092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarty MF. Chronic activation of AMP-activated kinase as a strategy for slowing aging. Med Hypotheses. 2004;63:334–339. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Apfeld J, O’Connor G, McDonagh T, DiStefano PS, Curtis R. The AMP-activated protein kinase AAK-2 links energy levels and insulin-like signals to lifespan in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3004–3009. doi: 10.1101/gad.1255404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zang M, et al. Polyphenols stimulate AMP-activated protein kinase, lower lipids, and inhibit accelerated atherosclerosis in diabetic LDL receptor-deficient mice. Diabetes. 2006;55:2180–2191. doi: 10.2337/db05-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nisoli E, et al. Calorie restriction promotes mitochondrial biogenesis by inducing the expression of eNOS. Science. 2005;310:314–317. doi: 10.1126/science.1117728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez-Lluch G, et al. Calorie restriction induces mitochondrial biogenesis and bioenergetic efficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1768–1773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510452103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Z, et al. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell. 1999;98:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80611-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoon JC, et al. Control of hepatic gluconeogenesis through the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Nature. 2001;413:131–138. doi: 10.1038/35093050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodgers JT, et al. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1α and SIRT1. Nature. 2005;434:113–118. doi: 10.1038/nature03354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lerin C, et al. GCN5 acetyltransferase complex controls glucose metabolism through transcriptional repression of PGC-1α. Cell Metab. 2006;3:429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheadle C, Vawter MP, Freed WJ, Becker KG. Analysis of microarray data using Z score transformation. J Mol Diagn. 2003;5:73–81. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baur JA, Sinclair DA. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: the in vivo evidence. Nature Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:493–506. doi: 10.1038/nrd2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SY, Volsky DJ. PAGE: parametric analysis of gene set enrichment. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng J, Bussiere F, Hekimi S. Mitochondrial electron transport is a key determinant of life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Cell. 2001;1:633–644. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kenyon C. A conserved regulatory mechanism for aging. Cell. 2001;105:165–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kapahi P, et al. Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2004;14:885–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaeberlein M, et al. Regulation of yeast replicative life span by TOR and Sch9 in response to nutrients. Science. 2005;310:1193–1196. doi: 10.1126/science.1115535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ingram DK, et al. Calorie restriction mimetics: an emerging research field. Aging Cell. 2006;5:97–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hipkiss AR. Does chronic glycolysis accelerate aging? Could this explain how dietary restriction works? Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1067:361–368. doi: 10.1196/annals.1354.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taub R. Liver regeneration: from myth to mechanism. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:836–847. doi: 10.1038/nrm1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu X, Sonntag WE. Growth hormone-induced nuclear translocation of Stat-3 decreases with age: modulation by caloric restriction. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:E903–E909. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.5.E903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilsey J, Scarpace PJ. Caloric restriction reverses the deficits in leptin receptor protein and leptin signaling capacity associated with diet-induced obesity: role of leptin in the regulation of hypothalamic long-form leptin receptor expression. J Endocrinol. 2004;181:297–306. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1810297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olsen A, Vantipalli MC, Lithgow GJ. Checkpoint proteins control survival of the postmitotic cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2006;312:1381–1385. doi: 10.1126/science.1124981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Z, et al. Cidea-deficient mice have lean phenotype and are resistant to obesity. Nature Genet. 2003;35:49–56. doi: 10.1038/ng1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Howitz KT, Sinclair DA. In: Handbook of the Biology of Aging. Masoro EJ, Austad SN, editors. Elsevier; Boston: 2006. pp. 63–104. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.