Abstract

PD-L1 is an immunoinhibitory molecule that suppresses the activation of T cells, leading to the progression of tumors. Overexpression of PD-L1 in cancers such as gastric cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, esophageal cancer, pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, and bladder cancer is associated with poor clinical outcomes. In contrast, PD-L1 expression correlates with better clinical outcomes in breast cancer and merkel cell carcinoma. The prognostic value of PD-L1 expression in lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and melanoma is controversial. Blocking antibodies that target PD-1 and PD-L1 have achieved remarkable response rates in cancer patients who have PD-L1-overexpressing tumors. However, using PD-L1 as an exclusive predictive biomarker for cancer immunotherapy is questionable due to the low accuracy of PD-L1 immunohistochemistry staining. Factors that affect the accuracy of PD-L1 immunohistochemistry staining are as follows. First, antibodies used in different studies have different sensitivity. Second, in different studies, the cut-off value of PD-L1 staining positivity is different. Third, PD-L1 expression in tumors is not uniform, and sampling time and location may affect the results of PD-L1 staining. Therefore, better understanding of tumor microenvironment and use of other biomarkers such as gene marker and combined index are necessary to better identify patients who will benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade therapy.

Keywords: PD-L1, prognostic value, checkpoint blockade, immunotherapy, clinical outcome

Introduction

The classic T cell activation is regulated by two signal transduction pathways: one is antigen dependent, and the other is antigen independent. The antigen-independent signaling includes positive and negative second signals. PD-1 and CTLA-4 are two immune-inhibitory checkpoint molecules that suppress T cell-mediated immune responses, leading to the development of tumors.1 Cancer immunoediting is a process that consists of immunosurveillance and tumor progression.2 It has three phases: elimination, equilibrium, and escape. In elimination phase, tumor cells are recognized by upregulated tumor antigen expression and killed by different types of immune effector cells. In equilibrium phase, tumor cells change into variants and induce immunosuppression to avoid constant immune pressure, resulting in a state of functional dormancy of the tumor. In escape phase, various immunosuppressive molecules and cytokines are activated by the tumor cells and contribute to tumor outgrowth, causing clinically apparent disease. PD-L1 is a PD-1 ligand that plays an important role in the inhibition of T cell-mediated immune response. Binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 causes the exhaustion of effector T cells and immune escape of tumor cells, leading to poor prognosis. In rare cases, positive PD-L1 expression has been reported to be associated with better clinical outcome. Clinical trials have demonstrated that monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that target PD-L1 or its receptor PD-1 prevent the inhibitory effects of PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and enhance T cell functions, leading to impressive outcomes in patients with melanoma, renal cell carcinoma (RCC), non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and bladder cancer.3–5 However, the predictive effects of PD-L1 in response to PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in some tumors are not conclusive, and the indication of PD-L1 expression in tumors remains controversial and needs to be understood profoundly. This review focuses on PD-L1 expression and its association with clinical outcomes in different cancers and factors affecting the accuracy of prediction of PD-L1. We also discuss the value of PD-L1 in predicting the clinical efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockades in cancer patients.

Expression and biological function of PD-L1

PD-L1 is mainly expressed on the surface of tumor cells and antigen-presenting cells in various solid malignancies such as squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, melanoma, and carcinomas of the brain, thyroid, thymus, esophagus, lung, breast, gastrointestinal tract, colorectum, liver, pancreas, kidney, adrenal cortex, bladder, urothelium, ovary, and skin.6–12 In tumor microenvironment, PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and other tumor-promoting cells is caused by two mechanisms, constitutive mechanism and induced mechanism, both of which depend on two binding sites of IRF-1.13 For example, in BRAFV600-mutated melanoma, PD-L1 expression is a result of cancer cells’ adaptive response to immune attack evoked by cytokines, or a constitutive expression which is a result of oncogenic processes.14 PD-L1 is rarely expressed on normal tissues but inducibly expressed on tumor site, which makes PD-L1 pathway uniquely different from other coinhibitory pathways,15 indicating that the selective expression of PD-L1 may have some association with clinical outcomes of the cancer patients and can be a selective target for antitumor therapy.

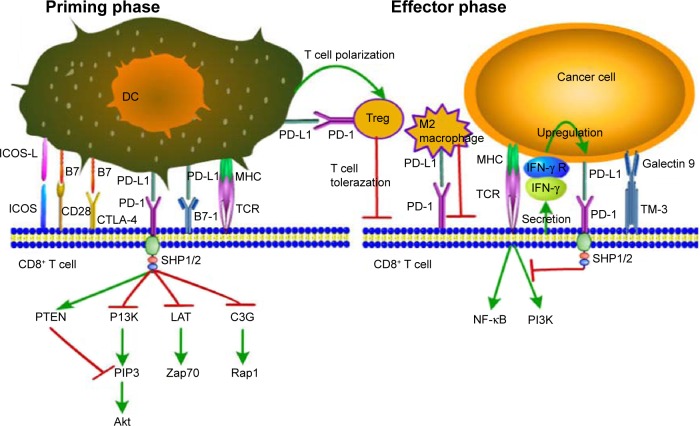

PD-1 (CD279), a PD-L1 receptor, is expressed on CD4−CD8− thymocytes and CD4+CD8+ T cells during thymic development and is selectively expressed on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, monocytes, natural killer T cells, B cells, and dendritic cells upon induction by TCR and cytokine arousal.16,17 In chronically infected mice model, high expression of PD-1 on T cells leads to T cell exhaustion and makes the exhausted CD8+ T cells lose effector function of secreting cytokines such as IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α.18 Binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 leads to the formation of PD-1/TCR inhibitory microcluster that recruits SHP1/2 molecule and dephosphorylates multiple members of TCR signaling pathway, leading to the shut-off of T cell activation through induction of apoptosis, reduction of proliferation, and inhibition of cytokine secretion (Figure 1). However, whether all kinds of cancers utilize the same action mechanism of PD-L1 signaling, that is, whether different prognosis of different cancers is caused by different PD-L1 mechanisms, remains inconclusive and needs to be further explored.

Figure 1.

PD-1/PD-L1 signaling: decreased CD8+ T cell proliferation, survival, and cytokine production.

Abbreviations: DC, dendritic cell; Treg, regulatory T cell; ICOS, inducible costimulator; ICOS-L, inducible costimulator-ligand; CD28, cluster of differentiation 28; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; PD-1, programmed death-1; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; TCR, T cell receptor; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IFN-γR, interferon-γ Receptor.

PD-1/PD-L1 pathway plays a prominent role in immune regulation by delivering inhibitory signals to maintain the balance in T cell activation, tolerance, and immune-mediated tissue damage. It exerts significant inhibitory functions in persistent antigenic stimulation environment such as exposure to self-antigen, chronic viral infection, and tumor.19–21 PD-L1 can also serve as a receptor transmitting antiapoptotic signal to tumor cells to protect them from apoptosis. Moreover, Shi et al22 have demonstrated that PD-L1 may have oncogenic function during colon cancer carcinogenesis. PD-L1 not only inhibits T cell proliferation and cytokine production but also enhances T cell activation.23 The explanation of this contradictory phenomenon is unknown.

In normal tissues, PD-1 signaling in T cells regulates immune responses to decrease damage to adjacent tissue, and counteracts the development of autoimmunity by promoting tolerance to self-antigens. PD-L1 receptor is also expressed on the surface of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs), a subset of CD4+ T cells that play a critical role in maintaining immune tolerance and weakening immune responses, to promote the development, maintenance, and immunosuppressive function of Tregs through inhibiting mTOR and AKT phosphorylation.24

Prognostic value of PD-L1 in malignancies

Table 1 summarizes the studies on the prognostic value of PD-L1 in different malignancies. Some malignancies such as hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic cancer (PC), gastric cancer, RCC, esophageal cancer (EC), and ovarian cancer can generate an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by expressing high-aggregate PD-L1 to avoid cytolysis by activated T cells. It may explain why overexpression of high-aggregate PD-L1 in tumors leads to poor prognosis in cancer patients. Interestingly, several long-term follow-up investigations have found an inverse correlation between PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and poor prognosis of patients. Additionally, in lung cancer, colorectal cancer (CRC), and melanoma, PD-L1 expression has both positive and negative prediction values. In thymoma and thymic carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, and cervical cancer, PD-L1 expression alone is not of prognostic value but is of significant prediction value when combined with other indicators such as CD8+/Foxp3+ T cell ratio.

Table 1.

Prognostic value of PD-L1 in different malignancies

| Disease | N | Detection method; PD-L1 detection antibody | Location of PD-L1 expression | PD-L1 tumor surface expression cut-off for positivity | TIL or other immunocytes associated with PD-L1 expression | Other clinicopathological factors associated with PD-L1 expression | Clinical outcomes | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thymoma and thymic carcinoma | 101 and 38 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (clone E1L3N) | 70% of thymic carcinoma (type C) and 23% of thymoma (types A, AB, and B) samples were positive for PD-L1 | 1% | NA | Higher PD-L1 expression was more likely to exhibit male, more advanced pathological features, including WHO classification type and Masaoka–Koga stage | PD-L1 positivity was not a significant negative factor of OS | Katsuya et al6 |

| Adrenocortical carcinoma | 28 | Paraffin IHC; monoclonal anti-PD-L1 antibody (405.9A11) | PD-L1 expression was detected both on tumor cell membrane and in TIMCs | 5% | NA | PD-L1 positivity on either tumor cell membrane or in TIMCs was not significantly associated with higher stage at diagnosis, higher tumor grade, and excessive hormone secretion | PD-L1 expressed on both tumor cell membrane and in TIMCs with no relationship with 5-year OS | Fay et al9 |

| Head and neck squamous cancer | 24 | Frozen IHC; anti-PD-L1 (5H1) | Eleven of 24 specimens had intracytoplasmic staining, eleven of 24 tumors had membrane reactivity, and ten of 24 had both | NA | NA | 16 of 24 specimens had PD-L1 staining | NA | Strome et al10 |

| Malignant brain tumors | 83 | FACS; anti-PD-L1 (BD Pharmingen Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) | 61% of brain tumors (but no WHO grade 1 tumors) expressed PD-L1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Jacobs et al11 |

| Glioma | 54 | Frozen IHC; anti-PD-L1 (clone MIH1; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) | NA | NA | NA | PD-L1 expression was closely correlated with the grade of the tumor | NA | Wilmotte et al12 |

| 10 | Frozen IHC; anti-PD-L1 (5H1) | Strong PD-L1 expression was detected in all ten glioma samples examined | NA | NA | NA | NA | Wintterle et al82 | |

| Lung cancer | 109 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (clone not specified) | PD-L1 expression on membrane and in cytoplasm of tumors with cluster and scattered patterns | NA | CD1α+ TIDC was increased in PD-L1+ portions of tumor and had higher expression of PD-L1 than CD83+ DCs | PD-L1+ cells in adenocarcinoma were more than in squamous cell carcinoma | PD-L1 positivity correlated with survival shorter than 3 years after lobectomy | Mu et al25 |

| 164 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (Lifespan Biosciences, Seattle, WA, USA); flow cytometry | PD-L1 was detected on membrane or in the cytoplasm (or both) of tumor cells and stromal lymphocytes in the surgically resected tumor specimens | NA | NA | PD-L1 expression is significantly higher in females, never smokers, those with adenocarcinoma histology, and those with EGFR mutations | PD-L1 overexpression was associated with a significantly shorter OS for NSCLC patients and had independent negative prognostic value | Azuma et al26 | |

| 204 and 340 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (clone 5H1) | NA | NA | PD-L1 protein and mRNA expression was consistently associated with increased local lymphocytic infiltrate | In Greek cohort, PD-L1 expression had association with tumor stage and inflammation, while in Yale cohort, with histology and inflammation | Patients with PD-L1 expression above the detection threshold showed statistically significant better outcome | Velcheti et al27 | |

| 163 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (Proteintech Group Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) | PD-L1 expressed on membrane of tumor cells | 5% | The degree of T lymphocytes infiltration was slightly higher in PD-L1-positive tumors than in PD-L1-negative ones | Higher PD-L1 expression was correlated with higher grade differentiation and vascular invasion | Positive PD-L1 expression had better RFS. Advanced-stage and positive VPSI were significant risk factors for poor prognosis of OS | Yang et al28 | |

| 214 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (clone 5H1, laboratory developed) | PD-L1 predominately expressed on membrane and minimally expressed in cytoplasm | 5% | PD-L1 expression had no significant correlation with infiltrating lymphocytes | NA | PD-L1 was not of independent prognostic value in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung | Boland et al29 | |

| 120 and 10 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 | NA | NA | NA | PD-L1 overexpression was related to poor tumor cell differentiation and advanced TNM stage | PD-L1– NSCLC patients had longer overall 5-year survival than PD-L1+ patients. PD-L1 status had independent prognostic value of NSCLC | Chen et al62 | |

| 52 | Frozen IHC; anti-B7-H1 (MIH1) | PD-L1 expression in cytoplasm or on membrane or both, in focal or scattered patterns in all 52 specimens of NSCLC | NA | In a subset of five patients, the amount of T lymphocytes infiltration was significantly reduced in PD-L1-expressing tumor regions | No correlation was observed between PD-L1 expression and clinicopathological characteristics | No correlation between PD-L1 expression and patient survival | Konishi et al81 | |

| Gastric cancer | 111 | Paraffin IHC; anti-Foxp3+ (polyclonal antibody, Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA) and anti-PD-L1 (polyclonal antibody; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) | 70 of 111 cases demonstrated PD-L1 expression on the membrane or in the cytoplasm | 10% | Significant correlation was found between the infiltration of Foxp3+ Tregs and the expression of PD-L1 on the tumor cells and TILs | High-level Foxp3+ Tregs and PD-L1 expression led to lymph node metastasis and an advanced clinicopathological stage | Enhanced expression of Foxp3+ Tregs and PD-L1 exhibited a lower OS rate and a worse prognosis | Hou et al30 |

| 102 | Paraffin IHC; anti-B7-H1 (2H11) | PD-L1 was expressed mainly in the cytoplasm; some nuclear membrane localization was also present | NA | NA | 42.2% of gastric carcinoma tissues were PD-L1+. PD-L1 correlated with tumor size, invasion, and lymph node metastasis | PD-L1 expression was an independent prognostic factor and correlated with poorer survival | Wu et al31 | |

| 107 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (polyclonal antibody) | 54 of 107 cases had positive PD-L1 expression | NA | NA | Positive PD-L1 expressions were significantly associated with depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis, pathological type, higher T stage, and higher differentiation | PD-L1-positive gastric cancers were significantly associated with a poor prognosis | Qing et al32 | |

| 205 | Paraffin IHC, FACS; anti-PD-L1 | 88 of 205 gastric carcinoma tissues were PD-L1 positive and were mainly distributed in cytoplasm and on membrane of the tumor cells | NA | IFN-γ and CD3+ T cells infiltration was found in carcinoma tissues | High PD-L1 expression was correlated with age, carcinoma location, and differentiation | NA | Jiang et al83 | |

| CRC | 143 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (ab58810; Abcam) | 64 patients (44.8%) showed positive PD-L1 expression in the cytoplasm and on the membrane | NA | NA | PD-L1 was significantly associated with cell differentiation status and TNM stage | Positive PD-L1 expression showed a trend of shorter survival time; PD-L1 expression is an independent predictor of colorectal carcinoma prognosis | Shi et al22 |

| 1,491 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 mAb (clone 27A2; MBL International Corporation, Woburn, MA, USA) | Strong PD-L1 expression was observed in 37% of MMR-proficient and in 29% of MMR-deficient CRCs | NA | In MMR-proficient CRC, correlation between strong PD-L1 expression and infiltration by CD8+ lymphocytes was found | PD-L1 expression in MMR-proficient CRC was significantly associated with early T stage, absence of lymph node metastases, lower tumor grade, and absence of vascular invasion | PD-L1 expression was paradoxically associated with improved survival in MMR-proficient CRC | Droeser et al33 | |

| 185 | Paraffin IHC; polyclonal anti-PD-L1 antibody | PD-L1 was expressed in cytoplasm and on membrane of the tumor cells | NA | CD3+ T cells in PD-L1+ specimens were significantly lower than that in PD-L1− patients but no difference of CD8+ T cells | Positive tumor PD-L1 expression was associated with lymph node metastasis | High PD-L1 was closely correlated with poor prognosis | Liang et al35 | |

| 56 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 | Cytoplasm and/or membrane | NA | A significant correlation between Tregs infiltration and PD-L1 expression was found | PD-L1 expression was positively correlated to the infiltration depth, lymph node metastasis, and advanced Duke’s stage | NA | Zhao et al85 | |

| Esophageal cancer | 41 | Frozen IHC, mRNA analysis; anti-PD-L1 (MIH1, mouse immunoglobulin G1) | 18 of 41 positive cases expressed PD-L1 or PD-L2 on the plasma membrane and in the cytoplasm of cancer cells | 10% | No significant correlation was found between PD-L1 expression and tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes. PD-L2 expression was inversely correlated with tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells | PD-L1-positive status was associated with advanced stage of cancer with positive lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis | PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression led to significantly poorer prognosis | Ohigashi et al36 |

| 99 | Paraffin IHC, FACS; anti-PD-L1 (NBP1-03220; Novus International, St Louis, MO, USA) | 82 of 99 patients demonstrated positive membranous/cytoplasmic PD-L1 staining, and 79 of 99 patients demonstrated positive nuclear PD-L1 staining | NA | PD-L1 expression was found significantly associated with the infiltrating density of Foxp3+ Tregs | Membranous or cytoplasmic PD-L1 expression was correlated with tumor invasion depth, and not correlated with other clinicopathological factors. Nuclear PD-L1 expression was significantly correlated with tumor invasion depth | Positive PD-L1 expression on membrane or in cytoplasm led to poorer OS but positive nuclear PD-L1 staining did not | Chen et al37 | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 51 | Frozen IHC, FACS; anti-human PD-L1 (MIH1, mouse immunoglobulin G1) | PD-L1 was expressed mainly on the plasma membrane and in the cytoplasm of cancer cells | 10% | PD-L1 expression was inversely correlated with tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes, particularly CD8+ T cells | There was no significant correlation between tumor PD-L1 status and clinical indicators including tumor status, nodal status, metastatic status, and pathologic stage | PD-L1+ patients had a significantly poorer prognosis than the PD-L1− patients. PD-L1 was an independent prognostic factor | Nomi et al8 |

| 81 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (MIH1; eBioscience) | PD-L1 was located primarily in the cytoplasm | 5% | PD-L1 resulted in the inhibition of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell activation and promotion of tumor growth | PD-L1 significantly correlated with the pathological grade and TNM stage | PD-L1-positive status was a prognostic indicator of poor disease-specific survival | Wang et al38 | |

| 40 and 10 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (monoclonal number: 2H11) | PD-L1 was intensely expressed in pancreatic carcinoma tissues, and weakly expressed in cytoplasm of islet cells | 10% | NA | PD-L1 expression was significantly associated with the staging of tumor and preoperative serum CA199 level | PD-L1 was an independent factor for poor prognosis | Chen et al39 | |

| 40 and 8 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (clone 130002; R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) | PD-L1 was located primarily in the cytoplasm of the tumor cells | NA | NA | PD-L1 expression was significantly associated with poor tumor differentiation and advanced tumor stage | PD-L1 overexpression in human pancreatic carcinoma tissues might have associations with tumor progression and invasiveness | Geng et al40 | |

| Malignant pleural mesothelioma | 106 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (clone 5H1-A3) | Cytoplasmic and/or membranous | 5% | NA | PD-L1 positivity was less likely to undergo therapeutic surgery and more likely to be a sarcomatoid mesothelioma subtype | PD-L1 was expressed in a substantial proportion of malignant pleural mesotheliomas and was associated with poor survival | Mansfield et al51 |

| Merkel cell carcinoma | 67 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (5H1) | PD-L1 expressed on membrane of tumor cells and TILs | 5% | A high density of CD8+ cells was associated with PD-L1 expression by tumor cells and by TILs | Expression of PD-L1 by either tumor cells or infiltrating immune cells did not correlate with patient’s sex, age, or pathologic stage | Tumor cell PD-L1 expression, but not TIL PD-L1 expression, was associated with improved OS | Lipson et al61 |

| MEL | 59 | Paraffin IHC; anti-B7-H1 (clone 27A2, MBL International Corporation) | PD-L1 expressed in tumor cell cytoplasm | NA | NA | Higher PD-L1 expression was found in high tumor stage, primary tumors with lymphonodus metastasis, and metastatic lymphonodus | PD-L1 expression was an independent predictor of poor OS and DFS | Hino et al63 |

| 150 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 mAb (5H1) | Membranous PD-L1 expression by melanocytes within the tumors and in the TILs | 5% | Almost all PD-L1+ tumors were associated with TILs, whereas only 28% of PD-L1− tumors were associated with TIL | PD-L1 expression was associated with the superficial spreading and nodular MEL subtypes and not with MEL stage | PD-L1 expression was associated with improved survival in metastatic MEL but not primary invasive MEL | Taube et al64 | |

| Cervical cancer | 115 | Paraffin IHC; anti-B7-H1 (5H1) | PD-L1 expressed on tumor cell membrane and throughout tumor bed | NA | PD-L1 expression was associated with higher Foxp3+ T cells infiltration but not with CD8+ T cells | In patients with PD-L1+ or PD-L1− tumors, more than half of the infiltrating CD8+ T cells and half of the Foxp3+ T cells expressed PD-1 | PD-L1 expression had no independent prognosis value; OS of patients with PD-L1+ tumors and a low CD8+/Foxp3+ T cell ratio was better than in patients with a PD-L1− tumor and a low CD8+/Foxp3+ T-cell ratio | Karim et al65 |

| Bladder cancer | 50 | Paraffin IHC; anti-human PD-L1 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) | PD-L1 expressed in the cytoplasm or on the membrane of tumor cells | 10% | NA | PD-L1 expression was strongly associated with the pathological grade, clinical stage, and recurrence of bladder cancer | PD-L1-positive group had a lower survival rate than negative group. PD-L1 was of independent prognostic value in bladder cancer | Wang et al68 |

| Differentiated thyroid carcinoma | 407 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 polyclonal antibody (prediluted; ab82059; Abcam) | PD-L1 expression was detected in the cytoplasm of tumor cells | NA | Elevated levels of PD-L1 protein were associated with the presence of CD4+, CD8+, CD20+, and Foxp3+ lymphocytes | Elevated levels of PD-L1 protein were associated with tumor-associated macrophages, and the presence of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Higher PD-L1 mRNA level was associated with stages II–IV and higher age | PD-L1 positivity had no prognostic value | Cunha et al69 |

| Sarcoma | 50 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 | PD-L1 expressed on plasma membrane | 1% | Positive tumor PD-L1 expression and lymphocytic PD-L1 expression were associated with high-density CD8+ cells | PD-L1 expression had no association with various clinicopathological factors | There was no association between OS and PD-L1 expression in tumor or immune infiltrates | D’Angelo et al70 |

| Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma | 181 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (clone A3) | 84 of 181 positive cases demonstrated both membranous and cytoplasmic staining | 5% | NA | PD-L1 expression was associated with worse N stage and distant metastasis | No correlation was found between PD-L1 expression and patient survival | Ukpo et al71 |

| ICC | 31 | Paraffin IHC, functional assays; anti-PD-L1 (Abcam) | Varying degrees of PD-L1 expression on plasma membrane and in cytoplasm of cancer cells were found in all 31 ICC cases | NA | Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes were significantly lower in III–IV and poorly differentiated tumors. A significant inverse correlation between tumor-related PD-L1 expression and CD8+ TILs count was found | Tumor-related PD-L1 expression was significantly correlated with a poorer histological differentiation and a more advanced pTNM stage | NA | Ye et al72 |

| Multiple myeloma | 82 | FACS, Western blot analysis, mRNA analysis; anti-PD-L1 (M1H1 for FACS, N20 for Western blot analysis) | PD-L1 was detected in most multiple myeloma plasma cell samples | NA | NA | NA | NA | Liu et al73 |

| Leukemia | 30 | FACS, functional assays, frozen IHC; anti-PD-L1 (5H1) | 17 of 30 samples of human leukemia cells were B7-H1+ | NA | NA | NA | NA | Salih et al74 |

| 60 | Real-time PCR, IHC; anti-PD-L1 | PD-L1 expressed mainly on the plasma membrane of cancer cells | 2.0 for real-time PCR | NA | PD-L1 was significantly higher in the relapse M5 patients and those with complicated pulmonary infections | PD-L1 status was defined to be an independent prognostic factor; PD-L1-positive patients had a poorer prognosis than the negative patients | Chen et al89 | |

| HCC | 141 | Paraffin IHC; anti-human PD-L1 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA); FACS with PE-conjugated anti-PD-L1 | NA | NA | NA | Circulating PD-L1 expression was closely correlated with intratumoral PD-L1 expression. PD-1/PD-L1 expression was associated with tumor size and blood vessel invasion | Patients with higher expression of circulating PD-L1 had a significantly shorter OS and tumor-free survival than those with lower expression | Zeng et al57 |

| 240 and 125 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (eBioscience); Western blot analysis | PD-L1 was shown on the cell membrane, in the cytoplasm, or both in a focal or scattered pattern | NA | Significant positive correlation between PD-L1 expression and Foxp3+ Treg cell infiltration was found | PD-L1 expression was an independent prognostic factor for tumor vascular invasion, encapsulation, and TNM stage | Patients with PD-L1+ tumors had poorer DFS and OS than patients with PD-L1− tumors; PD-L1 status was an independent prognostic factor for DFS, and PD-L1+ patients were nearly two times more likely to suffer from relapse after resection than PD-L1− patients | Gao et al75 | |

| 56 | Paraffin IHC, FACS; anti-PD-L1 (BioLegend); FACS with PE-conjugated PD-L1 (eBioscience) | Cytoplasmic and membranous | NA | CD8+ T cells were mainly distributed around the PD-L1+ portion of tumor nest | NA | NA | Shi et al76 | |

| 26 | Frozen IHC; anti-PD-L1 (MIH1; eBioscience) | PD-L1 was expressed on the membrane of tumor cells; focal or scattered | NA | PD-1+ T cells accumulated within tumors and in peritumoral areas | 24 of 26 HCC specimens expressed PD-L1; PD-L1 expression was associated with hepatitis B virus infection and with earlier tumor stage | NA | Wang et al84 | |

| RCC | 429 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (5H1) | PD-L1 expression on both tumor cells and lymphocytes | 10% | NA | This combined PD-L1 expression was associated with regional lymph node involvement, distant metastases, nuclear grade, and histologic tumor necrosis, all of which have been shown to portend a poor prognosis | Positive PD-L1 expression was close to three times more likely to die from RCC compared with negative PD-L1 expression patients. The combination of increased tumor cell PD-L1 and lymphocyte PD-L1 is an even stronger predictor of patient outcome | Thompson et al58 |

| 306 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (5H1) | NA | 5% | NA | PD-L1+ tumors were associated with TNM stage III or IV, tumor size of $5 cm, nuclear grade 3 or 4, and coagulative tumor necrosis | Patients with PD-L1+ tumors had increased risk of death from RCC and overall mortality and decreased 5-year survival | Thompson et al66 | |

| 196 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (clone 5H1) | PD-L1 expression on both tumor cells and lymphocytes | 10% | NA | High PD-L1 expression was associated with regional lymph node involvement, distant metastases, advanced nuclear grade, and tumor necrosis | Patients with high PD-L1 expression was significantly more likely to die of RCC | Thompson et al77 | |

| UCB | 65 | Frozen IHC; anti-PD-L1 (MIH1) | PD-L1 present on plasma membrane and/or in cytoplasm of urothelial cancer cells in a focal pattern | 12.2% | In 13 examined cases, most TILs expressed high levels of PD-1 | PD-L1 expression correlated with WHO grade and primary tumor classification | Increased PD-L1 expression was associated with poor survival and increased possibility of postresection recurrence | Nakanishi et al7 |

| 160 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (405.9A11) | PD-L1 expressed on tumor cell membrane and TIMCs | 5% | NA | PD-L1 expression had no association with various clinicopathological factors | Positive PD-L1 expression in TIMCs associated with longer survival in metastatic tumors | Bellmunt et al52 | |

| 410 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 | PD-L1 expression was detected on cell membrane and occasionally in cytoplasm | 5% | Tumor expression of PD-L1 was significantly associated with TIL expression of PD-1 | PD-L1 expression was significantly associated with advanced tumor stage and a greater degree of TILs | PD-L1 expression independently predicted increased all-cause mortality after cystectomy for patients with organ-confined tumors | Boorjian et al78 | |

| 280 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (clone 5H1) | PD-L1 expressed on plasma membrane | 1% | NA | PD-L1 expression was associated with high-grade tumors and tumor infiltration by mononuclear cells | Increasing levels of PD-L1 expression correlate with increased local aggressiveness of this cancer | Inman et al79 | |

| 302 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 | PD-L1 expression primarily on the cell membrane; cytoplasmic staining was occasionally detected | 5% | NA | PD-L1 was not associated with various clinicopathological factors | In patients with organ-confined UCB, PD-L1 expression was associated with an increased risk of overall mortality | Xylinas et al80 | |

| Ovarian cancer | 70 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (clone 27A2) | NA | NA | PD-L1 expression inversely correlated with intraepithelial CD8+ TIL count | PD-L1 had no statistically significant correlation with various clinicopathological factors | High expression of PD-L1 had worse 5-year survival rate and OS rate | Hamanishi et al59 |

| 70 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 (27A2; MBL International Corporation) | NA | NA | Negative correlation between CD8+ cell infiltration and PD-L1 tumor expression | NA | High PD-L1 expression had independent negative prognostic value | Hamanishi et al67 | |

| NA | FACS, functional assays; anti-PD-L1 (BD Pharmingen Inc.) for FACS, 5H1 for functional assays | PD-L1 present on nearly all myeloid DCs from tumor ascites and from tumor-draining lymph nodes | NA | NA | NA | NA | Curiel et al86 | |

| Breast cancer | 636 | RNAscope assay | PD-L1 mRNA expressed in nearly 60% of breast tumor | NA | Higher PD-L1 mRNA expression was significantly associated with increased TILs. The presence of elevated TILs was significantly associated with ER-negative status | PD-L1 mRNA expression was significantly associated with the presence of elevated TILs but not other clinicopathological factors | PD-L1 mRNA expression was associated with longer recurrence-free survival | Schalper et al60 |

| 44 | FACS, frozen IHC; anti-PD-L1 (MIH1; eBioscience) | PD-L1 expressed both on membrane and in cytoplasm | NA | NA | Intratumoral PD-L1 expression was associated with histologic stage III-negative, estrogen receptor-negative, and progesterone receptor-negative patients. TIL PD-L1 was associated with large tumor size, histologic grade 3, positivity of Her2/neu status, and increased tumor lymphocyte infiltration | NA | Ghebeh et al87 | |

| WT | 191 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 | Eleven tumors expressed PD-L1. Tumors with AH were more likely to express PD-L1 compared to FH tumors | NA | NA | PD-L1 expression within WT correlates with biological aggressiveness, including stage and histology | Tumor PD-L1 expression was significantly predictive of cancer recurrence | Routh et al88 |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | 139 | Paraffin IHC; anti-PD-L1 | PD-L1 expression was detected in 132 patients, which was located on tumor tissue | NA | PD-1 and PD-L1 coexpression leading to T cell exhaustion | PD-L1 expression had no significant correlation with clinicopathological factors such as age, tumor stage, lymph node metastasis, and clinical TNM staging | High expression of PD-L1 in tumor tissue significantly correlated with a poor prognosis of DFS | Zhang et al90 |

Abbreviations: TIL, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NA, not available; WHO, World Health Organization; TIMCs, tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; DCs, dendritic cells; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; RFS, relapse-free survival; VPSI, visceral pleural surface invasion; OS, overall survival; TNM, tumor–node–metastasis; CRC, colorectal cancer; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MMR, mismatch repair; Tregs, regulatory T cells; DFS, disease-free survival; MEL, melanoma; ICC, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; pTNM, pathological TNM; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PE, phycoerythrin; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; UCB, urothelial cancer of the bladder; WT, Wilms’ tumor; AH, anaplastic histology; FH, favorable histology.

Lung cancer

Two studies demonstrated that PD-L1 expression on tumor cells is correlated with poor prognosis in NSCLC patients. Both the studies detected PD-L1 expression both on membrane and in cytoplasm of tumor cells, but the cut-off value for PD-L1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) positivity was not mentioned.25,26 Azuma et al26 revealed that expression of high-aggregate PD-L1 on tumor cells is associated with EGFR gene mutations. Mu et al25 evaluated the intensity of PD-L1 expression in 109 NSCLC specimens. By IHC analysis, strong association was found between PD-L1 expression and shorter survival time in adenocarcinoma patients.

Two other studies showed a positive correlation between better clinical outcomes and PD-L1 expression. Velcheti et al27 assessed the predictive value of PD-L1 expression in two cohorts with 204 and 340 specimens, respectively. Tumor PD-L1 expression was found in 36% (Greek) and 25% (Yale) of the cases. Patients with PD-L1 expression above the detection threshold showed significantly better outcome. In 2014, Yang et al28 reported that patients with positive PD-L1 expression on tumor cell membrane had better relapse-free survival. Importantly, Boland et al29 showed that PD-L1 is not of independent prognostic value in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Based on the above studies, we conclude that PD-L1 has controversial predictive function in lung cancer.

Gastric cancer

Three articles reported the negative prediction value of PD-L1 in gastric cancer patients. Hou et al30 found that 70 of 111 patients had positive PD-L1 expression either on membrane or in the cytoplasm of tumor cells, and there was a positive correlation between the expression of PD-L1 and poor prognosis. The cut-off value was 10% in their study. The study by Hou et al also demonstrated that the combination of increased number of Foxp3+ Tregs and increased expression of PD-L1 is an even stronger predictor of lower overall survival (OS) rate and worse prognosis as compared to each individual factor alone. The other two studies did not mention the cut-off values of PD-L1 IHC staining; both of them showed that PD-L1 is of independent prognostic value.31,32 Wu et al31 examined 43 of 102 specimens and found that PD-L1 expression is mainly in the cytoplasm of tumor cells. Qing et al32 showed that 54 of 107 cases had positive PD-L1 expression. Both studies demonstrated that PD-L1 expression is significantly associated with invasion and lymph node metastasis, which are poor prognostic factors of tumors. In conclusion, gastric cancer patients with positive PD-L1 expression have a significantly poorer prognosis than PD-L1-negative patients.

Colorectal cancer

PD-L1 expression in CRC has not been fully addressed so far. Nevertheless, a strong correlation between PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and discrepant clinical outcomes has been observed. In CRC gene spectrum, DNA mismatch repair (MMR) status, known as MMR proficient and MMR deficient, has clinical significance in predicting the prognosis upon PD-L1 expression on tumor cells.33 MMR-proficient tumors are characterized by concurrent expression of MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6, whereas MMR-deficient tumors are characterized by lacking of expression of at least one of these markers.34 Droeser et al33 analyzed PD-L1 expression in two subtypes of CRCs, including 1,197 MMR-proficient and 223 MMR-deficient CRCs. They detected strong PD-L1 expression in 37% of MMR-proficient and in 29% of MMR-deficient CRCs. PD-L1 expression is associated with improved survival in MMR-proficient CRCs, which might be due to concomitant increase of CD8+ T cells infiltration.

In contrast, another two studies showed that positive PD-L1 expression in tumor is an independent predictor of poor CRC prognosis.22,35 Thus, the predictive value of PD-L1 expression on tumor cells is controversial in CRC patients.

Esophageal cancer

Positive correlation between PD-L1 expression and poor prognosis in EC was reported by two studies.36,37 Ohigashi et al36 selected 10% as cut-off value and illustrated that 18 of 41 positive cases express PD-L1 or PD-L2 on the plasma membrane and in the cytoplasm of cancer cells. Although no significant correlation was found between PD-L1 expression and number of tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes, PD-L2 expression was found to be inversely correlated with number of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells. They also found that the expression of either PD-L1 or PD-L2 has significant prognostic value and the combination of expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 leads to significantly poorer prognosis in postoperative EC patients. Their result further demonstrates that the roles of PD-L1 and PD-L2 in tumor immune escape differ depending on tumor types.

In a study carried out by Chen et al,37 PD-L1 expression was found to be significantly associated with the infiltrating density of Foxp3+ Tregs, but the cut-off value of PD-L1 expression was not mentioned. They concluded that membrane PD-L1, but not nuclear PD-L1, expression is associated with poor OS in EC patients.

Pancreatic cancer

Four studies focused on PC have achieved similar results showing that PD-L1 expression in human pancreatic carcinoma tissues is associated with poor prognosis. Nomi et al8 recruited 51 PC patients and selected 10% as cut-off value of PD-L1 expression on tumor cells. They observed that PD-L1 expression is inversely correlated with number of tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes, particularly CD8+ T cells, which might be a reason for the poor prognosis of PD-L1+ patients. Similarly, Wang et al38 also found that PD-L1 inhibits activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in tumor microenvironment in spite of selecting 5% as cut-off value for PD-L1 expression. Inhibition of effector T cell function could promote tumor growth, which may explain the poor prognosis of PD-L1-positive patients. Chen et al39 confirmed that PD-L1 is an independent factor of poor prognosis and its expression is significantly associated with the stage of the tumor and preoperative serum CA199 level. Geng et al40 found that PD-L1 overexpression in human pancreatic carcinoma tissues might have associations with tumor progression and invasiveness, which has significant correlation with poor OS. Collectively, PD-L1 expression is correlated with poor clinical outcomes in PC.

PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in cancer therapy

PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a significant mechanism of immune suppression within tumor microenvironment. mAbs targeting PD-1 or PD-L1 could block the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and enhance T cell functions. Thus, mAbs to PD-1 and PD-L1, as well as PD-L2 fusion protein, are widely tested in different clinical trials. Pidilizumab, lambrolizumab, nivolumab, and AMP-224 are mAbs targeting PD-1, whereas BMS-936559, MEDI4736, MPDL3280A, and MSB0010718C are mAbs to PD-L1.41 These mAbs were used in the treatment of malignancies including melanoma, NSCLC, RCC, bladder cancer, CRC, and gastric cancer. The overall response rates achieved was 16%–100%.3,42 Consequently, an effective predictive biomarker is needed to select “real” patients who will benefit from cancer immunotherapy while avoiding unnecessary toxicity. Tumor PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker has been evaluated in many clinical trials. For example, CheckMate 03743 study confirmed that nivolumab has better clinical efficacy than chemotherapy. Weber et al43 randomly allocated 272 patients to nivolumab and 133 to investigator’s choice of chemotherapy. The pretreatment PD-L1-positive number was 134 (49%) and 67 (50%), respectively. Confirmed objective response rate (ORR) was found in 31.7% of the first 120 patients in the nivolumab group versus 10.6% of 47 patients in the group that received investigator’s choice of chemotherapy. Importantly, the complete response rates were 3.3% versus 0%. A Phase I expansion study was implemented by Powles et al44 to investigate the responsiveness of PD-L1-positive and PD-L1-negative patients to MPDL3280A. The PD-L1-positive patients achieved 43% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 26%–63%) response rate, whereas the PD-L1-negative patients achieved a response rate of 11% (95% CI: 4%–26%), demonstrating the therapeutic activity of MPDL3280A in PD-L1-positive patients with urothelial bladder cancer. Both the studies demonstrated that tumor PD-L1 expression is an effective predictor of the outcomes of cancer immunotherapy. Nevertheless, the predictive value of PD-L1 is not consistent in cancer patients. For instance, in Phase III trials of CheckMate 01745 and CheckMate 057,46 the clinical efficacy of nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated advanced or metastatic squamous NSCLC and non-squamous NSCLC was evaluated, respectively. The nivolumab group achieved longer OS (9.2 versus 6.0 months [P=0.00025] and 12.2 versus 9.4 months [P=0.0015], respectively) and higher ORR (20% versus 9% [P=0.0083] and 19% versus 12% [P=0.0246], respectively) than patients treated with doc-etaxel in two studies, but the better progression-free survival was only achieved in squamous NSCLC (CheckMate 017).45 Importantly, the beneficial effect of nivolumab in squamous NSCLC is irrelevant to PD-L1 expression, whereas in non-squamous NSCLC, PD-L1 expression is predictive of the benefit of nivolumab.46 Moreover, some PD-L1-negative patients also respond to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy. Therefore, using tumor PD-L1 expression as exclusionary predictive biomarker for the outcome of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy has its limitations.47

mAbs targeting PD-1/PD-L1 pathway have achieved impressive response rates in patients with melanoma, NSCLC, RCC, and bladder cancer, and the value of PD-L1 as a predictive biomarker for the outcomes of mAb therapy has been demonstrated in many studies.3–5 Other predictive biomarkers for the prognosis of PD-L1 mAb immunotherapy in cancers have also been investigated. In 2015, ASCO, a Phase II study, confirmed the first gene predictive biomarker – MMR deficiency could effectively predict PD-1 blockade efficacy. In 41 patients with or without MMR deficiency, the ORR was 40% for MMR-deficient CRC patients and 0% for MMR-proficient CRC patients. The progression-free survival rate was 78% for MMR-deficient CRC patients and 11% for MMR-proficient CRC patients.48 More biomarkers should be investigated to facilitate the accurate selection of patients who can benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy.

Explanations of PD-L1 prognostic and predictive value

IHC-based detection of PD-L1 has limitations because of its subjectivity in determining a clear definition of “positive” tumor PD-L1 staining.49,50 Antibodies used in different studies include M1H1, 5H1, 5H1-A3, 2H11, 27A2, 405.9A11, and E1L3N.6,10,12,31,33,51,52 Different PD-L1 antibody clones can be a reason for lower PD-L1 expression in some studies. In addition to technical issues with IHC, temporal and spatial factors should also be considered when assessing PD-L1 in cancers. Specimens that were obtained when PD-L1 overexpression in tumor microenvironment has already taken place or patients’ specimens that missed the pertinent tumor–immune interface may lead to a bias in PD-L1’s predictive value in cancers.53 Furthermore, interferon-γ secreted by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes may cause upregulation of PD-L1 on tumor cells, leading to the induction of T cell apoptosis via PD-L1 and PD-1 interaction. Collectively, the prognostic value of PD-L1 IHC relies on the time of biopsy that is associated with the development of the nidus and is related to previous therapies including chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Deng et al54 demonstrated that tumor PD-L1 expression is upregulated after irradiation in mouse models. Therefore, single-time point evaluation of PD-L1 expression may not reflect the real condition, and multiple sites sampling is necessary for the determination of PD-L1 expression.

Spatial impact is another consideration when assessing PD-L1 expression in cancers. PD-L1 expression status may differ in primary lesions versus metastatic lesions due to tumor heterogeneity. PD-L1 expression has two patterns, focal expression and diffuse expression.55 Even from the same sample, impertinent biopsy may result in a bias due to the focal nature of PD-L1 expression in many tumors. Assessment of PD-L1 expression in tumor or peritumor is also a question. Thus, selection of the optimum site for biopsy for assessing PD-L1 expression status remains challenging and needs further studies.

Difficulties in comparing different, sometimes even contrary, results also arise from the following considerations: available data are retrospective, patients have different clinical characteristics, tumor samples from different tumor types or different locations of the same tumor are heterogeneous, and PD-L1 positivity is defined by membrane and/or cytoplasmic PD-L1 immunostaining. Several studies have demonstrated that only cell membrane-expressed PD-L1 has biological significance.56 Therefore, it is more reasonable to analyze correlations between membrane PD-L1 protein, rather than intracellular PD-L1 protein or mRNA, and clinical outcomes.

MMR, the first gene predictive biomarker that bridges the immunotherapy and genomics, effectively predicts PD-1 blockade efficacy in various cancers. It is necessary to develop more genetic methods to improve the effective prediction of cancer immunotherapy, and select “real” patients who are most likely to benefit from the immunotherapy. As the candidates of predictive marker, CD8+ T lymphocytes and IFN-γ may be evaluated in consideration of their importance in tumor microenvironment.

Conclusion

Studies have demonstrated that binding of tumor PD-L1 to its receptor PD-1 on T cell surface inhibits infiltrating T cell activation and subsequent lysis of tumor cells. PD-L1 expression in tumors strongly correlates with poor prognosis in gastric cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, RCC, EC, PC, and ovarian cancer.30,37,39,57–59 However, opposite results have been observed in breast cancer and merkel cell carcinoma, where tumor PD-L1 expression correlates with a better prognosis.60,61 In lung cancer, CRC, and melanoma, PD-L1 expression has both positive and negative prediction value.33,35,62–64 The controversy in PD-L1’s diagnostic and predictive value may be due to the following reasons. First, IHC-based detection of PD-L1 has technical issues, and the results may not accurately reflect the real PD-L1 expression status. Second, detection of PD-L1 expression in tumors is affected by temporal and spatial factors, leading to erroneous interpretation of the results. In addition, PD-L1 expression heterogeneity should also be taken into consideration. All these factors illustrate the limitation of using tumor PD-L1 expression as an exclusive biomarker for cancer immunotherapy. However, we cannot ignore the value of PD-L1 expression in selecting patients who will benefit from immunotherapy. Many clinical trials have demonstrated that immunotherapy significantly improves progression-free survival in patients. Remarkably, the grade 3 or 4 adverse events were evidently decreased compared to chemotherapy.45,91–93

Other effective biomarkers such as gene marker or combined indexes and improved understanding of tumor microenvironment are needed to accurately determine which patients will benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 pathway blockade therapy and to avoid the unnecessary autoimmune side effects from overtreatment.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ichikawa M, Chen L. Role of B7-H1 and B7-H4 molecules in down-regulating effector phase of T-cell immunity: novel cancer escaping mechanisms. Front Biosci. 2005;10:2856–2860. doi: 10.2741/1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mittal D, Gubin MM, Schreiber RD, Smyth MJ. New insights into cancer immunoediting and its three component phases – elimination, equilibrium and escape. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;27:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohaegbulam KC, Assal A, Lazar-Molnar E, Yao Y, Zang X. Human cancer immunotherapy with antibodies to the PD-1 and PD-L1 pathway. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21(1):24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexandrov LB, Serena NZ, Wedge DC, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allison JP. Immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy: the 2015 Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1113–1114. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.11929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katsuya Y, Fujita Y, Horinouchi H, Ohe Y, Watanabe S, Tsuta K. Immunohistochemical status of PD-L1 in thymoma and thymic carcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2015;88(2):154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakanishi J, Wada Y, Matsumoto K, Azuma M, Kikuchi K, Ueda S. Overexpression of B7-H1 (PD-L1) significantly associates with tumor grade and postoperative prognosis in human urothelial cancers. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56(8):1173–1182. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0266-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nomi T, Sho M, Akahori T, et al. Clinical significance and therapeutic potential of the programmed death-1 ligand/programmed death-1 pathway in human pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(7):2151–2157. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fay AP, Signoretti S, Callea M, et al. Programmed death ligand-1 expression in adrenocortical carcinoma: an exploratory biomarker study. J Immunother Cancer. 2015;3:3. doi: 10.1186/s40425-015-0047-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strome SE, Dong H, Tamura H, et al. B7-H1 blockade augments adoptive T-cell immunotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63(19):6501–6505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs JF, Idema AJ, Bol KF, et al. Regulatory T cells and the PD-L1/PD-1 pathway mediate immune suppression in malignant human brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11(4):394–402. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilmotte R, Burkhardt K, Kindler V, et al. B7-homolog 1 expression by human glioma: a new mechanism of immune evasion. Neuroreport. 2005;16(10):1081–1085. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200507130-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SJ, Jang BC, Lee SW, et al. Interferon regulatory factor-1 is prerequisite to the constitutive expression and IFN-gamma-induced upregulation of B7-H1 (CD274) FEBS Lett. 2006;580(3):755–762. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khalili JS, Liu S, Rodríguez-Cruz TG, et al. Oncogenic BRAF(V600E) promotes stromal cell-mediated immunosuppression via induction of interleukin-1 in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(19):5329–5340. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8(8):793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, Honjo T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992;11(11):3887–3895. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, et al. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature. 2006;439:682–687. doi: 10.1038/nature04444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharpe AH, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R, Freeman GJ. The function of programmed cell death 1 and its ligands in regulating autoimmunity and infection. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(3):239–245. doi: 10.1038/ni1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okazaki T, Honjo T. PD-1 and PD-1 ligands: from discovery to clinical application. Int Immunol. 2007;19(7):813–824. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nurieva RI, Liu X, Dong C. Yin-Yang of costimulation: crucial controls of immune tolerance and function. Immunol Rev. 2009;229(1):88–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00769.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi SJ, Wang LJ, Wang GD, et al. B7-H1 expression is associated with poor prognosis in colorectal carcinoma and regulates the proliferation and invasion of HCT116 colorectal cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamazaki T, Akiba H, Koyanagi A, Azuma M, Yagita H, Okumura K. Blockade of B7-H1 on macrophages suppresses CD4+ T cell proliferation by augmenting IFN-gamma-induced nitric oxide production. J Immunol. 2005;175(3):1586–1592. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francisco LM, Sage PT, Sharpe AH. The PD-1 pathway in tolerance and autoimmunity. Immunol Rev. 2010;236:219–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mu CY, Huang JA, Chen Y, Chen C, Zhang XG. High expression of PD-L1 in lung cancer may contribute to poor prognosis and tumor cells immune escape through suppressing tumor infiltrating dendritic cells maturation. Med Oncol. 2011;28(3):682–688. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azuma K, Ota K, Kawahara A, et al. Association of PD-L1 overexpression with activating EGFR mutations in surgically resected nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(10):1935–1940. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Velcheti V, Schalper KA, Carvajal DE, et al. Programmed death ligand-1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Lab Invest. 2014;94:107–116. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang CY, Lin MW, Chang YL, Wu CT, Yang PC. Programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in surgically resected stage I pulmonary adenocarcinoma and its correlation with driver mutations and clinical outcomes. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(7):1361–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boland JM, Kwon ED, Harrington SM, et al. Tumor B7-H1 and B7-H3 expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Clin Lung Cancer. 2013;14(2):157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou J, Yu Z, Xiang R, et al. Correlation between infiltration of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and expression of B7-H1 in the tumor tissues of gastric cancer. Exp Mol Pathol. 2014;96(3):284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu C, Zhu Y, Jiang J, Zhao J, Zhang XG, Xu LN. Immunohistochemical localization of programmed death-1 ligand-1 (PD-L1) in gastric carcinoma and its clinical significance. Acta Histochem. 2006;108(1):19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qing Y, Li Q, Ren T, et al. Upregulation of PD-L1 and APE1 is associated with tumorigenesis and poor prognosis of gastric cancer. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2015;9:901–909. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S75152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Droeser RA, Hirt C, Viehl CT, et al. Clinical impact of programmed cell death ligand 1 expression in colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(9):2233–2242. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lugli A, Zlobec I, Baker K, et al. Prognostic significance of mucins in colorectal cancer with different DNA mismatch-repair status. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(5):534–539. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.039552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang M, Li J, Wang D, et al. T-cell infiltration and expressions of T lymphocyte co-inhibitory B7-H1 and B7-H4 molecules among colorectal cancer patients in northeast China’s Heilongjiang province. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(1):55–60. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohigashi Y, Sho M, Yamada Y, et al. Clinical significance of programmed death-1 ligand-1 and programmed death-1 ligand-2 expression in human esophageal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(8):2947–2953. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen L, Deng H, Lu M, et al. B7-H1 expression associates with tumor invasion and predicts patient’s survival in human esophageal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(9):6015–6023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L, Ma Q, Chen X, Guo K, Li J, Zhang M. Clinical significance of B7-H1 and B7-1 expressions in pancreatic carcinoma. World J Surg. 2010;34(5):1059–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0448-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen XL, Yuan SX, Chen C, Mao YX, Xu G, Wang XY. Expression of B7-H1 protein in human pancreatic carcinoma tissues and its clinical significance. Ai Zheng. 2009;28(12):1328–1332. doi: 10.5732/cjc.009.10245. Chinese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geng L, Huang D, Liu J, et al. B7-H1 up-regulated expression in human pancreatic carcinoma tissue associates with tumor progression. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134(9):1021–1027. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0364-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sznol M, Chen L. Antagonist antibodies to PD-1 and B7-H1 (PD-L1) in the treatment of advanced human cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(5):1021–1034. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spigel DR, Gettinger SN, Horn L, et al. Clinical activity, safety, and biomarkers of MPDL3280A, an engineered PD-L1 antibody in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(Suppl) abstr 8008. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, David M, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:375–384. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powles T, Eder JP, Fine GD, et al. MPDL3280A (anti-PD-L1) treatment leads to clinical activity in metastatic bladder cancer. Nature. 2014;515:558–562. doi: 10.1038/nature13904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolchok JD, Harriet K, Callahan MK, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:122–133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gandhi L, Balmanoukian A, Hui R, et al. Abstract CT105: MK-3475 (anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody) for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): antitumor activity and association with tumor PD-L1 expression. Cancer Res. 2014;74:CT105. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marti AM, Martinez P, Navarro A, et al. Concordance of PD-L1 expression by different immunohistochemistry (IHC) definitions and in situ hybridization (ISH) in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the lung. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(Suppl 5) abstr 7569. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mansfield AS, Roden AC, Peikert T, et al. B7-H1 expression in malignant pleural mesothelioma is associated with sarcomatoid histology and poor prognosis. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(7):1036–1040. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bellmunt J, Mullane SA, Werner L, et al. Association of PD-L1 expression on tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells and overall survival in patients with urothelial carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(4):812–817. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Latchman YE, Liang SC, Yin W, et al. PD-L1-deficient mice show that PD-L1 on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and host tissues negatively regulates T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(29):10691–10696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307252101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deng L, Liang H, Burnette B, et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(2):687–695. doi: 10.1172/JCI67313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marco G, Rowan AJ, Stuart H, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zeng Z, Shi F, Zhou L, et al. Upregulation of circulating PD-L1/PD-1 is associated with poor post-cryoablation prognosis in patients with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. PLos One. 2011;6(9):e23621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thompson RH, Dong H, Kwon ED. Implications of B7-H1 expression in clear cell carcinoma of the kidney for prognostication and therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(2 Pt 2):709s–715s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Iwasaki M, et al. Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes are prognostic factors of human ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(9):3360–3365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611533104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schalper KA, Velcheti V, Carvajal D, et al. In situ tumor PD-L1 mRNA expression is associated with increased TILs and better outcome in breast carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(10):773–2782. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lipson EJ, Vincent JG, Loyo M, et al. PD-L1 expression in the Merkel cell carcinoma microenvironment: association with inflammation, Merkel cell polyomavirus and overall survival. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1(1):54–63. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen YB, Mu CY, Huang JA. Clinical significance of programmed death-1 ligand-1 expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a 5-year-follow-up study. Tumori. 2012;98:751–755. doi: 10.1177/030089161209800612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hino R, Kabashima K, Kato Y, et al. Tumor cell expression of programmed cell death-1 ligand 1 is a prognostic factor for malignant melanoma. Cancer. 2010;116(7):1757–1766. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taube JM, Anders RA, Young GD, et al. Colocalization of inflammatory response with B7-h1 expression in human melanocytic lesions supports an adaptive resistance mechanism of immune escape. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(127):127–137. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Karim R, Jordanova ES, Piersma SJ, et al. Tumor-expressed B7-H1 and B7-DC in relation to PD-1+ T-cell infiltration and survival of patients with cervical carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(20):6341–6347. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thompson RH, Kuntz SM, Leibovich BC, et al. Tumor B7-H1 is associated with poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma patients with long-term follow-up. Cancer Res. 2006;66(7):3381–3385. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Abiko K, et al. The comprehensive assessment of local immune status of ovarian cancer by the clustering of multiple immune factors. Clin Immunol. 2011;141(3):338–347. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang Y, Zhuang Q, Zhou S, Hu Z, Lan R. Costimulatory molecule B7-H1 on the immune escape of bladder cancer and its clinical significance. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2009;29(1):77–79. doi: 10.1007/s11596-009-0116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cunha LL, Marcello MA, Morari EC, et al. Differentiated thyroid carcinomas may elude the immune system by B7H1 upregulation. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20(1):103–110. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.D’Angelo SP, Shoushtari AN, Agaram NP, et al. Prevalence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and PD-L1 expression in the soft tissue sarcoma microenvironment. Human Pathol. 2015;46(3):357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ukpo OC, Thorstad WL, Lewis JS. B7-H1 expression model for immune evasion in human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:113–121. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0406-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ye Y, Zhou L, Xie X, Jiang G, Xie H, Zheng S. Interaction of B7-H1 on intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cells with PD-1 on tumor-infiltrating T cells as a mechanism of immune evasion. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100(6):500–504. doi: 10.1002/jso.21376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu J, Hamrouni A, Wolowiec D, et al. Plasma cells from multiple myeloma patients express B7-H1 (PD-L1) and increase expression after stimulation with IFN-{gamma} and TLR ligands via a MyD88-, TRAF6-, and MEK-dependent pathway. Blood. 2007;110(1):296–304. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Salih HR, Wintterle S, Krusch M, et al. The role of leukemia-derived B7-H1 (PD-L1) in tumor-T-cell interactions in humans. Exp Hematol. 2006;34(7):888–894. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gao Q, Wang XY, Qiu SJ, et al. Overexpression of PD-L1 significantly associates with tumor aggressiveness and postoperative recurrence in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(3):971–979. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shi F, Shi M, Zeng Z, et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 upregulation promotes CD8(+) T-cell apoptosis and postoperative recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(4):887–896. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thompson RH, Gillett MD, Cheville JC, et al. Costimulatory molecule B7-H1 in primary and metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104(10):2084–2091. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boorjian SA, Sheinin Y, Crispen PL, et al. T-cell coregulatory molecule expression in urothelial cell carcinoma: clinicopathologic correlations and association with survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(15):4800–4808. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Inman BA, Sebo TJ, Frigola X, et al. PD-L1 (B7-H1) expression by urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and BCG-induced granulomata: associations with localized stage progression. Cancer. 2007;109(8):1499–1505. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xylinas E, Robinson BD, Kluth LA, et al. Association of T-cell co-regulatory protein expression with clinical outcomes following radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;40(1):121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Konishi J, Yamazaki K, Azuma M, Kinoshita I, Dosaka-Akita H, Nishimura M. B7-H1 expression on non-small cell lung cancer cells and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and their PD-1 expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5094–5100. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wintterle S, Schreiner B, Mitsdoerffer M, et al. Expression of the B7-related molecule B7-H1 by glioma cells: a potential mechanism of immune paralysis. Cancer Res. 2003;63(21):7462–7467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jiang D, Xu YY, Li F, Xu B, Zhang XG. The role of B7-H1 in gastric carcinoma: clinical significance and related mechanism. Med Oncol. 2014;31(11):268. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0268-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang BJ, Bao JJ, Wang JZ, et al. Immunostaining of PD-1/PD-Ls in liver tissues of patients with hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(28):3322–3329. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i28.3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhao LW, Li C, Zhang RI, et al. B7-H1 and B7-H4 expression in colorectal carcinoma: correlation with tumor FOXP3+ regulatory T-cell infiltration. Acta Histochem. 2014;116(7):1163–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Curiel TJ, Wei S, Dong H, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 improves myeloid dendritic cell-mediated antitumor immunity. Nat Med. 2003;9(5):562–567. doi: 10.1038/nm863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ghebeh H, Mohammed S, Al-Omair A, et al. The B7-H1 (PD-L1) T lymphocyte-inhibitory molecule is expressed in breast cancer patients with infiltrating ductal carcinoma: correlation with important high-risk prognostic factors. Neoplasia. 2006;8(3):190–198. doi: 10.1593/neo.05733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Routh JC, Ashley RA, Sebo TJ, et al. B7-H1 expression in Wilms tumor: correlation with tumor biology and disease recurrence. J Urol. 2008;179(5):1954–1959. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen X, Liu S, Wang L, Zhang W, Ji Y, Ma X. Clinical significance of B7-H1 (PD-L1) expression in human acute leukemia. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7(5):622–627. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.5.5689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang J, Fang W, Qin T, et al. Co-expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 predicts poor outcome in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2015;32(3):86. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Westin JR, Chu F, Zhang M, et al. Safety and activity of PD1 blockade by pidilizumab in combination with rituximab in patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma: a single group, open-label, Phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(1):69–77. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70551-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Armand P, Nagler A, Weller EA, et al. Disabling immune tolerance by programmed death-1 blockade with pidilizumab after autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results of an international Phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(33):4199–4206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:134–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]