Abstract

Aims

To review the evidence base for classifying compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) as a non-substance or “behavioral” addiction.

Methods

Data from multiple domains (e.g., epidemiological, phenomenological, clinical, biological) are reviewed and considered with respect to data from substance and gambling addictions.

Results

Overlapping features exist between CSB and substance-use disorders. Common neurotransmitter systems may contribute to CSB and substance-use disorders, and recent neuroimaging studies highlight similarities relating to craving and attentional biases. Similar pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments may be applicable to CSB and substance addictions, although considerable gaps in knowledge currently exist.

Conclusions

Despite the growing body of research linking compulsive sexual behavior to substance addictions, significant gaps in understanding continue to complicate classification of compulsive sexual behaviour as an addiction.

STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

The release of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) (1) altered addiction classifications. For the first time, the DSM-5 grouped a disorder not involving substance use (gambling disorder) together with substance-use disorders in a new category entitled, “Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders.” Although researchers had previously advocated for its classification as an addiction (2–4), the re-classification has sparked debate and it is not clear whether a similar classification will occur in the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) (5). In addition to considering gambling disorder as a non-substance-related addiction, DSM-5 committee members considered whether other conditions such as Internet-gaming disorder should be characterized as “behavioral” addictions (6). Although Internet-gaming disorder was not included in DSM-5, it was added to Section 3 for further study. Other disorders were considered but not included in DSM-5. Specifically, proposed criteria for hypersexual disorder (7) were excluded, generating questions about the diagnostic future of problematic/excessive sexual behaviors. Multiple reasons likely contributed to these decisions, with insufficient data in important domains likely contributing (8).

In the current paper, compulsive sexual behavior (CSB), defined as difficulties in controlling inappropriate or excessive sexual fantasies, urges/cravings, or behaviors that generate subjective distress or impairment in one’s daily functioning, will be considered, as will its possible relationships to gambling and substance addictions. In CSB, intense and repetitive sexual fantasies, urges/cravings, or behaviors may increase over time and have been linked to health, psychosocial, and interpersonal impairments (7, 9). Although prior studies have drawn similarities between sexual addiction, problematic hypersexuality/hypersexual disorder, and sexual compulsivity, we will use the term CSB to reflect a broader category of problematic/excessive sexual behaviors that subsumes all of the above terms.

The current paper considers classification of CSB by reviewing data from multiple domains (e.g., epidemiological, phenomenological, clinical, biological) and addressing some of the diagnostic and classification issues that remain unanswered. Centrally, should CSB (including excessive casual sex, viewing of pornography, and/or masturbation) be considered a diagnosable disorder, and if so, should it be classified as a behavioral addiction? Given the current research gaps on the study of CSB, we conclude with recommendations for future research and ways in which research can inform better diagnostic assessment and treatments efforts for persons seeing professional help for CSB.

DEFINING CSB

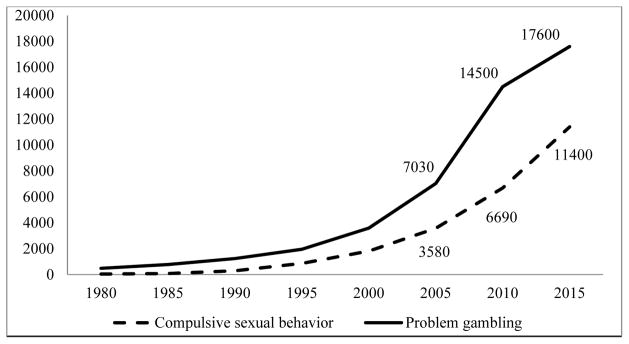

Over the last several decades, publications referencing the study of CSB have increased (Figure 1). Despite the growing body of research, little consensus exists among researchers and clinicians about the definition and presentation of CSB (10). Some view problematic/excessive engagement in sexual behaviors as a feature of hypersexual disorder (7), a nonparaphilic CSB (11), a mood disorder such as bipolar disorder (12), or as a “behavioral” addiction (13, 14). CSB is also being considered as a diagnostic entity within the category of impulse-control disorders in ICD-11 work (5).

Figure 1.

Number of publications in Google Scholar using key terms related to compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) or problem gambling

Note. On December 3, 2015, we entered the following key words into Google Scholar: “compulsive sexual behavior” OR “hypersexual disorder” OR “sexual addiction” OR “sexual compulsivity”; for problematic gambling, we entered the following words into Google Scholar: “gambling disorder” OR “pathological gambling” OR “disordered gambling” OR “problem gambling”.

Within the last decade, researchers and clinicians have begun conceptualizing CSB within the framework of problematic hypersexuality. In 2010, Martin Kafka proposed a new psychiatric disorder called hypersexual disorder for DSM-5 consideration (7). Despite a field trial supporting the reliability and validity of criteria for hypersexual disorder (15), the American Psychiatric Association excluded hypersexual disorder from DSM-5. Concerns were raised about the lack of research including anatomical and functional imaging, molecular genetics, pathophysiology, epidemiology, and neuropsychological testing (8). Others expressed concerns that hypersexual disorder could lead to forensic abuse or produce false positives diagnoses given the absence of clear distinctions between normal-range and pathological levels of sexual desires and behaviors (16–18).

Multiple criteria for hypersexual disorder share similarities with those for substance-use disorders (Table 1) (14). Both include criteria relating to impaired control (i.e., unsuccessful attempts to moderate or quit) and risky use (i.e., use/behavior leads to hazardous situations). Criteria differ for social impairment between hypersexual and substance-use disorders. Substance-use-disorder criteria also include two items assessing physiological dependence (i.e., tolerance and withdrawal), and criteria for hypersexual disorder do not. Unique to hypersexual disorder (with respect to substance-use disorders) are two criteria relating to dysphoric mood states. These criteria suggest hypersexual disorder’s origins might reflect maladaptive coping strategies, rather than a means of warding off withdrawal symptoms (e.g., anxiety associated with withdrawal from substances). Whether a person experiences withdrawal or tolerance related to a specific sexual behavior is debated, although it has been suggested that dysphoric mood states may reflect withdrawal symptoms for individuals with CSB who have recently cut back or quit engagement in problematic sexual behaviors (19). A final difference between hypersexual disorder and substance-use disorders involves diagnostic thresholding. Specifically, substance-use disorders require a minimum of two criteria, whereas hypersexual disorder requires four of five of the “A” criteria to be met. Currently, additional research is needed to determine the most appropriate diagnostic threshold for CSB (20).

Table 1.

Comparison of DSM-5 Substance Use Disorder and Hypersexual Disorder

| DSM-5 Substance Use Disorder (APA, 2013) Criteria | Hypersexual Disorder (Kafka, 2010) Criteria |

|---|---|

| A. Problematic substance use over at least 12 months | A. Problematic sexual behavior over at least six months. Need 4 of 5 criteria. |

| Impaired control and motivation | |

| 1. Substance is taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended | |

| 2. Persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use | 1. Repetitive but unsuccessful efforts to control or reduce sexual fantasies/urges/behaviors |

| 3. Significant time is spent in activities necessary to obtain substance, use the substance, or recover from its effects | 2. Excessive time is expended by sexual fantasies/urges or planning for sexual behavior |

| 4. Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use the substance | |

| Social impairment | |

| 5. Failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home due to substance use | Accounted for by clinical impairment in functioning |

| 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by use | |

| 7. Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are stopped/reduced due to substance use | |

| Risky use | |

| 8. Recurrent substance use in situations considered physically hazardous | 3. Repetitively engaging in sexual behavior while disregarding the risk for physical/emotional harm to self or others |

| 9. Continued use despite persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by substance | |

| Dependence | |

10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following:

|

No equivalent |

| 11. Withdrawal - Substance is taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms | |

| Dysphoric mood state/life stressors | |

| No equivalent | 4. Repetitively engaging in these sexual fantasies/urges/behaviors in response to dysphoric mood states |

| 5. Repetitively engaging in sexual fantasies/urges/behaviors in response to stressful life events | |

| Diagnostic Criteria: | |

| Severity: mild (2–3 criteria), moderate (4–5 criteria), and severe (6 or more criteria) | B. Clinically significant personal distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning associated with the frequency and intensity of these sexual fantasies/urges/behaviors |

| Substances: alcohol, cannabis, phencyclidine, other hallucinogen, inhalants, opioid, sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic, stimulant: specify amphetamine or cocaine, tobacco | C. Sexual fantasies/urges/behavior are not due to direct physiological effects of substance or to maniaD. Person is 18 years of age |

| Specify if: masturbation, pornography, sexual behavior with consenting adults, cybersex, telephone sex, strip clubs, other | |

Clinical characteristics of CSB

Insufficient data exist regarding CSB’s prevalence. Large-scale community data regarding prevalence estimates of CSB are lacking, making the true prevalence of CSB unknown. Researchers estimate rates ranging from 3–6% (7) with adult males comprising the majority (80% or higher) of affected persons (15). A large study of US university students found estimates of CSB to be 3% for men and 1% for women (21). Among US male military combat veterans, prevalence was estimated to be closer to 17% (22). Using data from the US National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), the lifetime prevalence rates of sexual impulsivity, a possible dimension of CSB, was found to be higher for men (18.9%) than women (10.9%) (23). Although important, we emphasize that similar gaps in knowledge did not prevent the introduction of pathological gambling into DSM-III in 1980 or the inclusion of Internet gaming disorder into section 3 of DSM-5 (see wide prevalence estimates ranging from about 1% to 50%, depending on how problematic Internet use is defined and thresholded (6)).

CSB appears more frequent among men as compared to women (7). Samples of university-aged (21, 24) and community members (15, 25, 26) suggest that men, as compared to women, are more likely to seek professional treatment for CSB (27). Among CSB men, the most reported clinically distressing behaviors are compulsive masturbation, pornography use, casual/anonymous sex with strangers, multiple sexual partners, and paid sex (15, 28, 29). Among women, high masturbation frequency, number of sexual partners and pornography use are associated with CSB (30).

In a field trial for hypersexual disorder, 54% of patients reported experiencing dysregulated sexual fantasies, urges, and behaviors prior to adulthood, suggesting an early onset. Eighty-two percent of patients reported experiencing a gradual progression of hypersexual-disorder symptoms over months or years (15). Progression of sexual urges over time is associated with personal distress and functional impairment across important life domains (e.g., occupational, familial, social, and financial) (31). Hypersexual individuals may have propensities to experience more negative than positive emotions, and self-critical affect (e.g., shame, self-hostility) may contribute to the maintenance of CSB (32). Given limited studies and mixed results, it is unclear whether CSB is associated with deficits in impaired decision-making/executive functioning (33–36).

In DSM-5, ‘craving’ was added as a diagnostic criterion for substance-use disorders (1). Likewise, craving appears relevant to the assessment and treatment of CSB. Among young adult men, craving for pornography correlated positively with psychological/psychiatric symptoms, sexual compulsivity, and severity of cybersex addiction (37–41). A potential role for craving in predicting relapse or clinical outcomes for CSB patients has not yet been examined.

In treatment-seeking patients, university students, and community members, CSB appears more common among European/white individuals compared to others (e.g., African-American, Latino, Asian-Americans) (15, 21). Limited data suggest that individuals seeking treatment for CSB may be of higher socioeconomic status compared to those with other psychiatric disorders (15, 42), although this finding might reflect greater access to treatment (including private-pay treatment given limitations in insurance coverage) for individuals with higher incomes. CSB has also been found among men who have sex with men (28, 43, 44) and is associated with HIV risk-taking behaviors (e.g., condomless anal intercourse) (44, 45). CSB is associated with elevated rates of sexual risk-taking in both heterosexual and non-heterosexual individuals, reflected in high rates of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among treatment-seeking patients (7, 15).

Psychopathology and CSB

CSB frequently occurs with other psychiatric disorders. About half of hypersexual individuals meet criteria for at least one DSM-IV mood, anxiety, substance-use, impulse-control, or personality disorder (22, 28, 29, 46). In 103 men seeking treatment for compulsive pornography use and/or casual sexual behaviors, 71% met criteria for a mood disorder, 40% for an anxiety disorder, 41% for a substance-use disorder, and 24% for an impulse-control disorder (47). Estimated rates of co-occurring CSB and gambling disorder range from 4% to 20% (25, 26, 47, 48). Sexual impulsivity is associated with multiple psychiatric disorders across sexes and particularly for women. Among women as compared to men, sexual impulsivity was more strongly associated with social phobia, alcohol-use disorder, and paranoid, schizotypal, antisocial, borderline, narcissistic, avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders (23).

NEUROBIOLOGICAL BASIS OF CSB

Understanding whether CSB shares neurobiological similarities with (or differences from) substance-use and gambling disorders would help inform ICD-11-related efforts and treatment interventions. Dopaminergic and serotonergic pathways may contribute to the development and maintenance of CSB, although this research is arguably in its infancy (49). Positive findings for citalopram in a double-blind placebo controlled study of CSB among a sample of men suggests possible serotonergic dysfunction (50). Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, may be effective at reducing both the urges and behaviors associated with CSB, consistent with roles in substance and gambling addictions and consistent with proposed mechanisms of opioid-related modulation of dopaminergic activity in mesolimbic pathways (51–53).

The most compelling evidence between dopamine and CSB relates to Parkinson’s disease. Dopamine replacement therapies (e.g., levodopa and dopamine agonists like pramipexole, ropinirole) have been associated with impulse-control behaviors/disorders (including CSB) among individuals with Parkinson’s disease (54–57). Among 3,090 Parkinson’s-disease patients, dopamine agonist use was associated with a 2.6-fold increase odds of having CSB (57). CSB among Parkinson’s-disease patients has also been reported to remit once the medication has been discontinued (54). Levodopa has also been associated with CSB and other impulse-control disorders in Parkinson’s disease, as have multiple other factors (e.g., geographic location, marital status) (57).

The pathophysiology of CSB, currently poorly understood, is actively being researched. Dysregulated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-axis function has been linked to addictions and was recently identified in CSB. CSB men were more likely than non-CSB men to be dexamethasone-suppression-test non-suppressors and have higher adrenocorticotropic-hormone levels. The hyperactive hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in CSB men may underlie craving and CSB behaviors related to battling dysphoric emotional states (58).

Existing neuroimaging studies have focused primarily on cue-induced reactivity. Cue reactivity is clinically relevant to drug addictions, contributing to cravings, urges and relapses (59). A recent meta-analysis reported overlap between tobacco, cocaine, and alcohol cue reactivity in the ventral striatum, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and amygdala related to drug-cue reactivity and self-reported craving, suggesting that these brain regions may constitute a core circuit of drug craving across addictions (60). The incentive motivation theory of addictions posits that addiction is related to the enhanced incentive salience to drug-associated stimuli resulting in greater attentional capture, approach behaviors, expectancy and pathological motivation (or ‘wanting’) for drugs (61, 62). This theory has also been applied to CSB (63).

In college female students (64), individual differences in human reward-related brain activity in the nucleus accumbens in response to food and sexual images related prospectively to weight gain and sexual activity six months later. Heightened reward responsivity in the brain to food or sexual cues was associated with overeating and increased sexual activity, suggesting a common neural mechanism associated with appetitive behaviors. During fMRI, exposure to pornographic video cues compared to non-sexual exciting videos in CSB men relative to non-CSB men was associated with greater activation in the dorsal anterior cingulate, ventral striatum, and amygdala, regions implicated in drug-cue reactivity studies in drug addictions (63). Functional connectivity of these regions was associated with subjective sexual desire to the cues, but not liking, among men with CSB. Here, desire was taken as an index of ‘wanting’ as compared to ‘liking’. The men with CSB versus those without also reported heightened sexual desire and demonstrated greater anterior-cingulate and striatal activation in response to pornographic images (65).

CSB men as compared to those without also showed greater attentional biases to sexually explicit cues, suggesting a role for early attentional orienting responses towards pornographic cues (66). CSB men also demonstrated greater choice preference for cues conditioned to both sexual and monetary stimuli compared to men without CSB (67). The greater early attentional bias to sexual cues was associated with greater approach behaviors towards conditioned sexual cues, thus supporting incentive motivation theories of addiction. CSB subjects also showed a preference for novel sexual images and greater dorsal-cingulate habituation to repeated exposure to sexual pictures, with the degree of habituation correlating with enhanced preference for sexual novelty (67). The access to novel sexual stimuli may be specific to online availability of novel materials.

Among Parkinson’s-disease subjects, exposure to sexual cues increased sexual desire in those with CSB compared to those without (68); enhanced activity in limbic, paralimbic, temporal, occipital, somatosensory, and prefrontal regions implicated in emotional, cognitive, autonomic, visual, and motivational processes was also observed. CSB patients’ increased sexual desire correlated with increased activations in the ventral striatum, and cingulate and orbitofrontal cortices (68). These findings resonate with those in drug addictions in which increased activation of these reward-related regions is seen in response to cues related to the specific addiction, in contrast to blunted responses to general or monetary rewards (69, 70). Other studies have also implicated prefrontal regions; in a small diffusion tensor imaging study, CSB versus non-CSB men showed higher superior-frontal mean-diffusivity (71).

In contrast, other studies focusing on individuals without CSB have emphasized a role for habituation. In non-CSB men, a longer history of pornography viewing was correlated with lower left putaminal responses to pornographic photos, suggesting potential desensitization (72). Similarly, in an event-related-potential study with men and women without CSB, those reporting problematic use of pornography had a lower late positive potential to pornographic photos relative to those not reporting problematic use. The late positive potential is commonly elevated in response to drug cues in addiction studies (73). These findings contrast with, but are not incompatible with, the report of enhanced activity in the fMRI studies in CSB subjects; the studies differ in stimuli type, modality of measure and the population under study. The CSB study used infrequently shown videos as compared to repeated photos; the degree of activation has been shown to differ to videos versus photos and habituation may differ depending on the stimuli. Furthermore, in those reporting problematic use in the event-related-potential study, the number of hours of use was relatively low (problem: 3.8 (SD=1.3) versus control: 0.6 (SD=1.5) hours/week) as compared to the CSB fMRI study (CSB: 13.21 (SD=9.85) versus control: 1.75 (SD=3.36) hours/week). Thus, habituation may relate to general use, with severe use potentially associated with enhanced cue-reactivity. Further larger studies are required to examine these differences.

Genetics of CSB

Genetic data relating to CSB are sparse. No genome-wide-association study of CSB has been performed. A study of 88 married couples with CSB found high frequencies of first-degree relatives with substance-use disorders (40%), eating disorders (30%), or pathological gambling (7%) (74). A twin study suggested genetic contributions accounted for 77% of the variance relating to problematic masturbatory behaviors, whereas 13% was attributable to non-shared environmental factors (75). Substantial genetic contributions also exist for substance and gambling addictions (76, 77). Using twin data (78), the estimated proportion of variation in liability for gambling disorder due to genetic influences is approximately 50%, with higher proportions seen for more severe problems. Inherited factors associated with impulsivity may represent a vulnerability marker for the development of substance-use disorders (79); however, whether these factors increase odds of developing CSB has not yet been explored.

ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT OF CSB

Over the last decade, research on the diagnosis and treatment of CSB has increased (80). Various researchers have proposed diagnostic criteria (13) and developed assessment tools (81) to aid clinicians in the treatment of CSB; however, the reliability, validity, and utility of many of these scales remain largely unexplored. Few measures have been validated, limiting their generalizability for clinical practice.

Treatment interventions for CSB require additional research. Few studies have evaluated the efficacies and tolerabilities of specific pharmacological (53, 82–86) and psychotherapeutic (87–91) treatments for CSB. Evidence-based psychotherapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and acceptance-and-commitment therapy appear helpful for CSB (89, 91, 92). Likewise, serotonergic reuptake inhibitors (e.g., fluoxetine, sertraline, and citalopram) and opioid antagonists (e.g., naltrexone) have demonstrated preliminary efficacy in reducing CSB symptoms and behaviors, although large-scale randomized controlled trials are lacking. Existing medication studies have typically been case studies. Only one study (50) used a double-bind, placebo-controlled design when evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of a drug (citalopram) in the treatment of CSB.

No large randomized controlled trials exist examining the efficacy of psychotherapies in treating CSB. Methodological issues limit the generalizability of existing clinical outcomes studies, since most studies employ weak methodological designs, differ on inclusion/exclusion criteria, fail to use random assignment for treatment conditions, and do not include control groups necessary to conclude that the treatment worked (80). Large, randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate the efficacies and tolerabilities of medications and psychotherapies in treating CSB.

Alternative perspectives

The proposal of hypersexual disorder as a psychiatric disorder has not been uniformly embraced. Concerns have been raised that the label of ‘disorder’ pathologizes normal variants of healthy sexual behavior (93), or that excessive/problematic sexual behavior may be better explained as an extension of a pre-existing mental health disorder or poor coping strategies used to regulate negative affect states rather than a distinct psychiatric disorder (16, 18). Other researchers expressed concern that some individuals labeled with CSB may merely have high levels of sexual desire (18), with suggestions that difficulty controlling sexual urges and high frequencies of sexual behaviors and consequences associated with those behaviors may be better explained as a non-pathological variation of high sexual desire (94). In a large sample of Croatian adults, cluster analysis identified two meaningful clusters, one representing problematic sexuality and another reflecting high sexual desire and frequent sexual activity. Individuals in the problematic cluster reported more psychopathology compared to individuals in the high-desire/frequent-activity cluster (95). This suggests CSB may be organized more along a continuum of increasing sexual frequency and preoccupation, in which clinical cases are more likely to occur in the upper end of the continuum or dimension (96). Given the likelihood that there is considerable overlap between CSB and high sexual desire, additional research is needed to identify features most specifically associated with clinically distressing sexual behaviors.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

With the release of DSM-5, gambling disorder was reclassified with substance-use disorders. This change challenged beliefs that addiction occurred only by ingesting of mind-altering substances and has significant implications for policy, prevention, and treatment strategies (97). Data suggest that excessive engagement in other behaviors (e.g. gaming, sex, compulsive shopping) may share clinical, genetic, neurobiological, and phenomenological parallels with substance addictions (2, 14). Despite the increasing number of publications on CSB, multiple gaps in knowledge exist that would help more conclusively determine whether excessive engagement in sexual behaviors might best be classified as an addiction. In Table 2, we list areas where additional research is needed to increase understanding of CSB. Insufficient data are available regarding what clusters of symptoms may best constitute CSB or what threshold may be most appropriate for defining CSB (20). Such insufficient data complicate classification, prevention, and treatment efforts. While neuroimaging data suggest similarities between substance addictions and CSB, data are limited by small sample sizes, solely male heterosexual samples, and cross-sectional designs. Additional research is needed to understand CSB in women, underprivileged and racial/ethnic minority groups, gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgendered persons, individuals with physical and intellectual disabilities, and other groups.

Table 2.

Knowledge gaps relating to compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) and approaches for addressing the gaps

| Current gaps | Future directions |

|---|---|

| Defining CSB | Use cluster analysis to examine latent dimensions of CSB and investigate how best to threshold cases. |

| Prevalence data | Large-scale, population-based epidemiological studies examining prevalence of CSB in multiple geographic areas. Emphasis needed on assessing prevalence among racial/ethnic minority groups, women, gay, bisexual, transsexual, and low income/uninsured individuals/groups, as well as those with physical and intellectual disabilities, in order to mitigate against possible health disparities. |

| Longitudinal data | Naturalistic longitudinal studies assessing the trajectory of sexual behaviors and CSB across the lifespan. Using a cohort design, researchers should: (a) identify risk and protective factors for the development of CSB; and, (b) measure the progression of CSB symptoms over time. |

| Clinical data | Assess prevalence of medical and mental health comorbidities as related to CSB in the general population. |

| Neuropsychological data | Examine whether there are any intelligence, memory, language, executive functioning, and visuospatial differences found among CSB patients compared to non-diagnosed individuals. |

| Neurobiological data | Use neuroimaging techniques to examine neurochemical and functional changes in the brains of CSB patients. Assess the relationship between brain structure and function and treatment outcomes. Assesses relationships between craving for sex/pornography and treatment outcomes (e.g., relapse). |

| Genetic data | Conduct genome-wide association studies (GWAS) on CSB. Examine genetic factors that may serve as vulnerability factors for the development of CSB. |

| Treatment | Well-powered randomized controlled trials examining efficacies and tolerabilities of psychotherapies and medications in treating CSB. |

| Screening | Develop standardized screening assessments for accurately diagnosing CSB. |

| Prevention | Create intervention programs aimed at promoting healthy and safe sexual behaviors among the public. Design advertisement campaigns aimed at raising awareness about “warning signs” and symptoms associated CSB, particularly risky sexual behaviors facilitated by the Internet. |

Another area needing more research involves considering how technological changes may be influencing human sexual behaviors. Given that data suggest that sexual behaviors are facilitated through Internet and smartphone applications (98–100), additional research should consider how digital technologies relate to CSB (e.g., compulsive masturbation to Internet pornography or sex chat rooms) and engagement in risky sexual behaviors (e.g., condomless sex, multiple sexual partners on one occasion). For example, whether increased access to Internet pornography and the use of websites and smartphone applications (e.g., Grindr, FindFred, Scruff, Tinder, Pure, etc.) designed to facilitate casual sex between consenting adults is associated with an increased reports of hypersexual behaviors awaits future research. As such data are collected, acquired knowledge should be translated into improved policy, prevention, and treatment strategies for persons most at risk for and impacted by CSB.

Debate points.

Is CSB a diagnosable condition?

Should CSB be classified as an addiction?

What are the pros and cons of considering sex as a potentially addictive behavior?

What data support the proposition that CSB might be best considered as a behavioral addiction?

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by support from the Department of Veterans Affairs, VISN 1 Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center, the National Center for Responsible Gaming, and CASAColumbia. The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies and reflect the views of the authors. The authors report that they have no financial conflicts of interest with respect to the content of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report that they have no financial conflicts of interest with respect to the content of this manuscript. Dr. Potenza has received financial support or compensation for the following: Dr. Potenza has consulted for and advised Lundbeck, Ironwood, Shire, INSYS and RiverMend Health; has received research support (to Yale) from the National Institutes of Health, Mohegan Sun Casino, the National Center for Responsible Gaming, and Pfizer pharmaceuticals; has participated in surveys, mailings or telephone consultations related to drug addiction, impulse control disorders or other health topics; has consulted for gambling and legal entities on issues related to impulse control; provides clinical care in the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services Problem Gambling Services Program; has performed grant reviews for the National Institutes of Health and other agencies; has edited or guest-edited journals or journal sections; has given academic lectures in grand rounds, CME events and other clinical or scientific venues; and has generated books or book chapters for publishers of mental health texts.

References

- 1.Association A. P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leeman RF, Potenza MN. A targeted review of the neurobiology and genetics of behavioral addictions: An emerging area of research. Canadian journal of psychiatry Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 2013;58:260. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petry NM. Should the scope of addictive behaviors be broadened to include pathological gambling? Addiction. 2006;101:152–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101:142–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant JE, Atmaca M, Fineberg NA, Fontenelle LF, Matsunaga H, VEALE D, et al. Impulse control disorders and “behavioural addictions” in the ICD-11. WPA. 2014;125 doi: 10.1002/wps.20115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petry NM, O’Brien CP. Internet gaming disorder and the DSM-5. Addiction. 2013;108:1186–1187. doi: 10.1111/add.12162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kafka MP. Hypersexual Disorder: A Proposed Diagnosis for DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39:377–400. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9574-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piquet-Pessôa M, Ferreira GM, Melca IA, Fontenelle LF. DSM-5 and the Decision Not to Include Sex, Shopping or Stealing as Addictions. Current Addiction Reports. 2014;1:172–176. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuzma JM, Black DW. Epidemiology, Prevalence, and Natural History of Compulsive Sexual Behavior. Psychiat Clin N Am. 2008;31:603-+. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kingston DA. Debating the Conceptualization of Sex as an Addictive Disorder. Current Addiction Reports. 2015:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coleman E, Raymond N, McBean A. Assessment and treatment of compulsive sexual behavior. Minnesota Medicine. 2003;86:42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McElroy SL, Pope HG, Jr, Keck PE, Jr, Hudson JI, Phillips KA, Strakowski SM. Are impulse-control disorders related to bipolar disorder? Compr Psychiatry. 1996;37:229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carnes PJ, Hopkins TA, Green BA. Clinical relevance of the proposed sexual addiction diagnostic criteria: relation to the Sexual Addiction Screening Test-Revised. J Addict Med. 2014;8:450–461. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kor A, Fogel YA, Reid RC, Potenza MN. Should hypersexual disorder be classified as an addiction? Sexual addiction & compulsivity. 2013;20:27–47. doi: 10.1080/10720162.2013.768132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reid RC, Carpenter BN, Hook JN, Garos S, Manning JC, Gilliland R, et al. Report of Findings in a DSM-5 Field Trial for Hypersexual Disorder. The journal of sexual medicine. 2012;9:2868–2877. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moser C. Hypersexual disorder: Searching for clarity. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2013;20:48–58. doi: 10.1080/10720162.2013.768132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakefield JC. The DSM-5’s proposed new categories of sexual disorder: The problem of false positives in sexual diagnosis. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2012;40:213–223. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winters J. Hypersexual disorder: A more cautious approach. Archives of sexual behavior. 2010;39:594–596. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9607-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia FD, Thibaut F. Sexual Addictions. Am J Drug Alcohol Ab. 2010;36:254–260. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.503823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reid RC. How should severity be determined for the DSM-5 proposed classification of hypersexual disorder? Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2015;4:221–225. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Odlaug BL, Lust K, Schreiber LR, Christenson G, Derbyshire K, Harvanko A, et al. Compulsive sexual behavior in young adults. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2013;25:193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith PH, Potenza MN, Mazure CM, McKee SA, Park CL, Hoff RA. Compulsive sexual behavior among male military veterans: Prevalence and associated clinical factors. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2014;3:214–222. doi: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.4.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erez G, Pilver CE, Potenza MN. Gender-related differences in the associations between sexual impulsivity and psychiatric disorders. Journal of psychiatric research. 2014;55:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodge B, Reece M, Cole SL, Sandfort TGM. Sexual compulsivity among heterosexual college students. J Sex Res. 2004;41:343–350. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Black DW, Kehrberg LL, Flumerfelt DL, Schlosser SS. Characteristics of 36 subjects reporting compulsive sexual behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:243–249. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raymond NC, Coleman E, Miner MH. Psychiatric comorbidity and compulsive/impulsive traits in compulsive sexual behavior. Compr Psychiat. 2003;44:370–380. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00110-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid RC, Garos S, Carpenter BN. Reliability, validity, and psychometric development of the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory in an outpatient sample of men. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2011;18:30–51. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgenstern J, Muench F, O’Leary A, Wainberg M, Parsons JT, Hollander E, et al. Non-paraphilic compulsive sexual behavior and psychiatric co-morbidities in gay and bisexual men. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2011;18:114–134. doi: 10.1080/10720162.2011.593420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scanavino MdT, Ventuneac A, Abdo CHN, Tavares H, Amaral MLSAd, Messina B, et al. Compulsive sexual behavior and psychopathology among treatment-seeking men in São Paulo, Brazil. Psychiatry research. 2013;209:518–524. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein V, Rettenberger M, Briken P. Self-Reported Indicators of Hypersexuality and Its Correlates in a Female Online Sample. The journal of sexual medicine. 2014;11:1974–1981. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spenhoff M, Kruger TH, Hartmann U, Kobs J. Hypersexual behavior in an online sample of males: associations with personal distress and functional impairment. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10:2996–3005. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reid RC. Differentiating emotions in a sample of men in treatment for hypersexual behavior. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2010;10:197–213. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mulhauser KR, Struthers WM, Hook JN, Pyykkonen BA, Womack SD, MacDonald M. Performance on the Iowa Gambling Task in a Sample of Hypersexual Men. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2014;21:170–183. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reid RC, Garos S, Carpenter BN, Coleman E. A surprising finding related to executive control in a patient sample of hypersexual men. The journal of sexual medicine. 2011;8:2227–2236. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reid RC, Karim R, McCrory E, Carpenter BN. Self-reported differences on measures of executive function and hypersexual behavior in a patient and community sample of men. International Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;120:120–127. doi: 10.3109/00207450903165577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schiebener J, Laier C, Brand M. Getting stuck with pornography? Overuse or neglect of cybersex cues in a multitasking situation is related to symptoms of cybersex addiction. Journal of behavioral addictions. 2015;4:14–21. doi: 10.1556/JBA.4.2015.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brand M, Laier C, Pawlikowski M, Schächtle U, Schöler T, Altstötter-Gleich C. Watching pornographic pictures on the internet: Role of sexual arousal ratings and psychological–psychiatric symptoms for using internet sex sites excessively. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2011;14:371–377. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kraus S, Rosenberg H. The Pornography Craving Questionnaire: Psychometric Properties. Archives of sexual behavior. 2014;43:451–462. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laier C, Pawlikowski M, Pekal J, Schulte FP, Brand M. Cybersex addiction: Experienced sexual arousal when watching pornography and not real-life sexual contacts makes the difference. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2013;2:100–107. doi: 10.1556/JBA.2.2013.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberg H, Kraus S. The relationship of “passionate attachment” for pornography with sexual compulsivity, frequency of use, and craving for pornography. Addict Behav. 2014;39:1012–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinstein AM, Zolek R, Babkin A, Cohen K, Lejoyeux M. Factors predicting cybersex use and difficulties in forming intimate relationships among male and female users of cybersex. Name: Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2015;6:54. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farré J, Fernández-Aranda F, Granero R, Aragay N, Mallorquí-Bague N, Ferrer V, et al. Sex addiction and gambling disorder: similarities and differences. Compr Psychiat. 2015;56:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, Cook KF, Grov C, Mustanski B. A psychometric investigation of the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men: An item response theory analysis. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10:3088–3101. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, Moody RL, Grov C. Hypersexual, Sexually Compulsive, or Just Highly Sexually Active? Investigating Three Distinct Groups of Gay and Bisexual Men and Their Profiles of HIV-Related Sexual Risk. AIDS and Behavior. 2015:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1029-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeagley E, Hickok A, Bauermeister JA. Hypersexual behavior and HIV sex risk among young gay and bisexual men. The Journal of Sex Research. 2014;51:882–892. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.818615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Black DW, Monahan P, Gabel J. Fluvoxamine in the treatment of compulsive buying. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:159–163. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kraus SW, Potenza MN, Martino S, Grant JE. Examining the psychometric properties of the Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale in a sample of compulsive pornography users. Compr Psychiat. 2015;59:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grant JE, Steinberg MA. Compulsive Sexual Behavior and Pathological Gambling. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2005;12:235–244. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kraus SW, Voon V, Potenza MN. Neurobiology of Compulsive Sexual Behavior: Emerging Science. Neuropsychopharmacology Reviews. 2016;41:385–386. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wainberg ML, Muench F, Morgenstern J, Hollander E, Irwin TW, Parsons JT, et al. A double-blind study of citalopram versus placebo in the treatment of compulsive sexual behaviors in gay and bisexual men. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2006;67:1968–1973. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim SW. Opioid antagonists in the treatment of impulse-control disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kraus SW, Meshberg-Cohen S, Martino S, Quinones LJ, Potenza MN. Treatment of compulsive pornography use with naltrexone: A case report. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;172:1260–1261. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15060843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raymond NC, Grant JE, Coleman E. Augmentation with naltrexone to treat compulsive sexual behavior: a case series. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2010;22:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klos KJ, Bower JH, Josephs KA, Matsumoto JY, Ahlskog JE. Pathological hypersexuality predominantly linked to adjuvant dopamine agonist therapy in Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Parkinsonism & related disorders. 2005;11:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leeman RF, Potenza MN. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: clinical characteristics and implications. Neuropsychiatry. 2011;1:133–147. doi: 10.2217/npy.11.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Voon V, Hassan K, Zurowski M, De Souza M, Thomsen T, Fox S, et al. Prevalence of repetitive and reward-seeking behaviors in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2006;67:1254–1257. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000238503.20816.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weintraub D, Koester J, Potenza MN, Siderowf AD, Stacy M, Voon V, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: a cross-sectional study of 3090 patients. Archives of neurology. 2010;67:589–595. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chatzittofis A, Arver S, Öberg K, Hallberg J, Nordström P, Jokinen J. HPA axis dysregulation in men with hypersexual disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;63:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Childress AR, Hole AV, Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ, McLellan AT, O’Brien CP. Cue reactivity and cue reactivity interventions in drug dependence. NIDA research monograph. 1993;137:73–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kühn S, Gallinat J. Common biology of craving across legal and illegal drugs–a quantitative meta-analysis of cue-reactivity brain response. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;33:1318–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Field M, Cox WM. Attentional bias in addictive behaviors: a review of its development, causes, and consequences. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2008;97:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The incentive sensitization theory of addiction: some current issues. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2008;363:3137–3146. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Voon V, Mole TB, Banca P, Porter L, Morris L, Mitchell S, et al. Neural correlates of sexual cue reactivity in individuals with and without compulsive sexual behaviours. PloS one. 2014;9:e102419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Demos KE, Heatherton TF, Kelley WM. Individual differences in nucleus accumbens activity to food and sexual images predict weight gain and sexual behavior. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:5549–5552. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5958-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Seok J-W, Sohn J-H. Neural substrates of sexual desire in individuals with problematic hypersexual behavior. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2015;9:321. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mechelmans DJ, Irvine M, Banca P, Porter L, Mitchell S, Mole TB, et al. Enhanced Attentional Bias towards Sexually Explicit Cues in Individuals with and without Compulsive Sexual Behaviours. PloS one. 2014;9:e105476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Banca P, Morris LS, Mitchell S, Harrison NA, Potenza MN, Voon V. Novelty, conditioning and attentional bias to sexual rewards. Journal of psychiatric research. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Politis M, Loane C, Wu K, O’Sullivan SS, Woodhead Z, Kiferle L, et al. Neural response to visual sexual cues in dopamine treatment-linked hypersexuality in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2013;136:400–411. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Balodis IM, Potenza MN. Anticipatory reward processing in addicted populations: a focus on the monetary incentive delay task. Biological psychiatry. 2015;77:434–444. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Limbrick-Oldfield EH, van Holst RJ, Clark L. Fronto-striatal dysregulation in drug addiction and pathological gambling: Consistent inconsistencies? NeuroImage: Clinical. 2013;2:385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miner MH, Raymond N, Mueller BA, Lloyd M, Lim KO. Preliminary investigation of the impulsive and neuroanatomical characteristics of compulsive sexual behavior. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2009;174:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kühn S, Gallinat J. Brain structure and functional connectivity associated with pornography consumption: the brain on porn. JAMA psychiatry. 2014;71:827–834. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prause N, Steele VR, Staley C, Sabatinelli D, Hajcak G. Modulation of late positive potentials by sexual images in problem users and controls inconsistent with “porn addiction”. Biological psychology. 2015;109:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schneider JP, Schneider BH. Couple recovery from sexual addiction/co addiction: results of a survey of 88 marriages. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity: The Journal of Treatment and Prevention. 1996;3:111–126. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Långström N, Grann M, Lichtenstein P. Genetic and environmental influences on problematic masturbatory behavior in children: A study of same-sex twins. Archives of sexual behavior. 2002;31:343–350. doi: 10.1023/a:1016224326301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Slutske WS, Eisen S, True WR, Lyons MJ, Goldberg J, Tsuang M. Common genetic vulnerability for pathological gambling and alcohol dependence in men. Archives of general psychiatry. 2000;57:666–673. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.True WR, Xian H, Scherrer JF, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Heath AC, et al. Common genetic vulnerability for nicotine and alcohol dependence in men. Archives of general psychiatry. 1999;56:655–661. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Slutske WS, Zhu G, Meier MH, Martin NG. Genetic and environmental influences on disordered gambling in men and women. Archives of general psychiatry. 2010;67:624–630. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Verdejo-García A, Lawrence AJ, Clark L. Impulsivity as a vulnerability marker for substance-use disorders: review of findings from high-risk research, problem gamblers and genetic association studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32:777–810. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hook JN, Reid RC, Penberthy JK, Davis DE, Jennings DJ. Methodological Review of Treatments for Nonparaphilic Hypersexual Behavior. Journal of sex & marital therapy. 2014;40:294–308. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2012.751075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Womack SD, Hook JN, Ramos M, Davis DE, Penberthy JK. Measuring hypersexual behavior. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2013;20:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Grant JE, Kim SW, Odlaug BL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist, naltrexone, in the treatment of kleptomania. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:600–606. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kafka M. Psychopharmacologic treatments for nonparaphilic compulsive sexual behaviors. CNS Spectr. 2000;5:49–59. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900012669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kafka MP, Hennen J. Psychostimulant augmentation during treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in men with paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders: a case series. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:664–670. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Raymond NC, Grant J, Kim S, Coleman E. Treatment of compulsive sexual behaviour with naltrexone and serotonin reuptake inhibitors: two case studies. International clinical psychopharmacology. 2002;17:201–205. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200207000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wainberg ML, Muench F, Morgenstern J, Hollander E, Irwin TW, Parsons JT, et al. A double-blind study of citalopram versus placebo in the treatment of compulsive sexual behaviors in gay and bisexual men. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1968–1973. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hardy SA, Ruchty J, Hull TD, Hyde R. A preliminary study of an online psychoeducational program for hypersexuality. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2010;17:247–269. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Orzack MH, Voluse AC, Wolf D, Hennen J. An ongoing study of group treatment for men involved in problematic Internet-enabled sexual behavior. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2006;9:348–360. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Twohig MP, Crosby JM. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for problematic internet pornography viewing. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Young KS. Cognitive behavior therapy with Internet addicts: treatment outcomes and implications. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007;10:671–679. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.9971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Young KS. Treatment outcomes using CBT-IA with Internet-addicted patients. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2013;2:209–215. doi: 10.1556/JBA.2.2013.4.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Young KS. Cognitive behavior therapy with Internet addicts: treatment outcomes and implications. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2007;10:671–679. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.9971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Giles J. No such thing as excessive levels of sexual behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35:641–642. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Steele VR, Staley C, Fong T, Prause N. Sexual desire, not hypersexuality, is related to neurophysiological responses elicited by sexual images. Socioaffective neuroscience & psychology. 2013;3 doi: 10.3402/snp.v3i0.20770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Carvalho J, Štulhofer A, Vieira AL, Jurin T. Hypersexuality and High Sexual Desire: Exploring the Structure of Problematic Sexuality. The journal of sexual medicine. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jsm.12865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Walters GD, Knight RA, Långström N. Is hypersexuality dimensional? Evidence for the DSM-5 from general population and clinical samples. Archives of sexual behavior. 2011;40:1309–1321. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9719-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Potenza M. Perspective: Behavioural addictions matter. Nature. 2015;522:S62–S62. doi: 10.1038/522S62a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Beymer MR, Weiss RE, Bolan RK, Rudy ET, Bourque LB, Rodriguez JP, et al. Sex on demand: geosocial networking phone apps and risk of sexually transmitted infections among a cross-sectional sample of men who have sex with men in Los Angeles county. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2014;90:567–572. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Holloway IW, Dunlap S, del Pino HE, Hermanstyne K, Pulsipher C, Landovitz RJ. Online Social Networking, Sexual Risk and Protective Behaviors: Considerations for Clinicians and Researchers. Current Addiction Reports. 2014;1:220–228. doi: 10.1007/s40429-014-0029-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Winetrobe H, Rice E, Bauermeister J, Petering R, Holloway IW. Associations of unprotected anal intercourse with Grindr-met partners among Grindr-using young men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/Hiv. 2014;26:1303–1308. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.911811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]