Abstract

Background and rationale

Coronary artery disease (CAD) and its pathological atherosclerotic process are closely related to lipids. Lipids levels are in turn influenced by dietary oils and fats. Saturated fatty acids increase the risk for atherosclerosis by increasing the cholesterol level. This study was conducted to investigate the impact of cooking oil media (coconut oil and sunflower oil) on lipid profile, antioxidant mechanism, and endothelial function in patients with established CAD.

Design and methods

In a single center randomized study in India, patients with stable CAD on standard medical care were assigned to receive coconut oil (Group I) or sunflower oil (Group II) as cooking media for 2 years. Anthropometric measurements, serum, lipids, Lipoprotein a, apo B/A-1 ratio, antioxidants, flow-mediated vasodilation, and cardiovascular events were assessed at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years.

Results

Hundred patients in each arm completed 2 years with 98% follow-up. There was no statistically significant difference in the anthropometric, biochemical, vascular function, and in cardiovascular events after 2 years.

Conclusion

Coconut oil even though rich in saturated fatty acids in comparison to sunflower oil when used as cooking oil media over a period of 2 years did not change the lipid-related cardiovascular risk factors and events in those receiving standard medical care.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Coconut oil, Sunflower oil, Cholesterol, Cooking medium

1. Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) resulting from atherosclerosis is closely associated with serum lipids.1, 2, 3 Dietary fats and oils influence the metabolism of lipids and increase the chance of CAD if the hyperlipidemic state persists for a long time. Atherogenic dyslipidemia is constituted by increased low-density lipoproteins (LDL), reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and elevated triglycerides. In a recent study of (Md-CCC) by principle component analysis, it is shown that this type of metabolic abnormality is predictive of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disesae.4 Since 1963 after the Framing harm heart trial, the fats and oils containing saturated fatty acids are considered one of the important causes for CAD.5 Aggressive lipid lowering strategies have shown reduced morbidity and mortality from CAD.6 Though the management of dyslipidemia by lipid lowering drugs is very effective,7, 8, 9, 10 modulating HDL to therapeutically significant level is not yet achieved.11 Genetic factors, life style, and dietary habits are responsible for the geographical variations in serum lipids. Most of the time, the concern regarding the dietary oil begins after the occurrence of a cardiac event or being diagnosed as having CAD.

1.1. Cooking oil media

CAD prevalence and risk factors are significantly high in the state of Kerala among the Indian states due to various reasons.12, 13 One of the contributing factors is proposed to be the saturated fatty acids contained in coconut oil which is the most commonly used cooking oil media. Sunflower oil rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids have become the second preferred cooking oil media over last few years. Polyunsaturated fatty acids in sunflower oil affect the lipid metabolism in a favorable manner. The oil and fat usage in a given population is influenced by the tradition, availability, and socioeconomic status and to certain extent the awareness.

1.2. The medium chain fatty acids and CAD

The medium chain fatty acids metabolism is different from the long chain fatty acids present in other fats and oil.14, 15 There are only epidemiological data and small short-term interventions with the coconut oil and its association with CAD.16, 17, 18 Previous work from our institution showed that there were no differences in lipid profile (serum total cholesterol, triacylglycerols, and cholesterol in lipoprotein fractions) between persons taking coconut oil or sunflower oil.19 Higher intake of coconut oil did not cause any significant increase in the concentration of lauric acid in blood among coconut oil consumers. Moreover, serum lipid values did not show significant variation between animals fed with coconut oil or sunflower oil. Coconut oil intake did not cause hypercholesterolemia or oxidative stress in rabbits.20 In another study, the fatty acid content of the coronary plaque (endarterectomy specimen) did not show any difference between coconut oil consumers versus sunflower oil consumers.21 Since these studies were done in free living subjects, many compounding factors like eating outside, quantity of oil, duration of consumption, and physical activity could not be assessed correctly.

In this context, a study evaluating the impact of coconut oil on cardiovascular events and risk factors as a cooking oil media in the community is warranted. In this study, we evaluated the impact of coconut oil and sunflower oil as a cooking medium on the cardiovascular events and risk factors in patients with stable coronary heart disease receiving the standard medical care.

2. Materials and method

2.1. Design

Randomized single blinded clinical trial.

2.2. Sample size

Since this is the first of this kind of study with cooking oil media, no publications could be located in the existing literature and hence this was taken as a pilot study. A total of 200 patients satisfying the criteria for recruitment were randomly allocated to two groups. Block randomization was done with 5 blocks each having 40 cases for allocation. This was done just to avoid the non-availability of required sample size and to keep randomization live with the available number of patients. However, 200 patients were available at the end of study.

2.3. Subjects

The subjects were selected from the patients attending the outpatient department of our hospital as per the selection criteria. CAD was diagnosed by various methods like coronary angiogram, Echocardiography, ECG evidence of myocardial infarction, stress perfusion scan, and multidetector coronary angiogram. Subjects were included in the study if they achieve optimal control of diabetes and lipid levels. Patients with uncontrolled hypothyroidism, renal failure creatinine >2 mg/dl and liver failure, and other illness limiting the life expectancy <2 years were excluded.

Approval from scientific committee and institutional ethic committee was obtained as per guidelines. All subjects signed informed consent before randomization.

The funding agencies were (1) Coconut development board – India and (2) Amrita Institute of Medical Science and Research Center. None of the sponsors had any role in the study design and data analysis.

2.4. Anthropometric measurements

2.4.1. Body mass index

Height was measured with subjects in bare foot using standardized extendable measuring rod. Weight was measured with an electronic Dura weighing machine during empty stomach.

2.4.2. Percentage body fat

Skin fold thickness was measured with a Harpenden skin fold caliper by using a three-site system in this study. For men it was triceps, subscapular and chest whereas in women triceps, abdomen, and suprailiac sites were used. These measurements were then used in the Siri equation to derive the percentage body fat.

2.4.3. Waist hip ratio

Waist circumference was measured with the patient in the held expiration position midway between the twelfth rib and anterior superior iliac spine. The hip measurement was taken at the level of greater trochanter.

2.5. Dietary intervention

Each arm containing 100 patients was assigned to branded commercial coconut oil or sunflower oil as per block randomization. The oils were given to subjects as well as to the family members so as to ensure the compliance. The subjects were asked to use the assigned oil for cooking. A 24 h dietary recall was applied to all subjects before the commencement of the study to test their dietary pattern. The total energy requirements and the amount of oil required to meet 15% of daily calories were calculated on the basis of 24 h recall. During the study, 7 day recall and a diet diary were used to monitor the adherence of study subjects to the assigned oil and food pattern.

2.6. Flow-mediated vasodilatation

Noninvasive endothelial function assessment was carried out with flow-mediated vasodilatation (FMD) of brachial artery. Ischemia was induced by inflating sphygmomanometer pressure cuff for 5 min over forearm (distal occlusion) by 50 mmHg above the systolic pressure in a fasting state. Imaging of brachial artery was done using a 7–12 MHz linear array transducer fixed to a custom-made probe holder. ECG Gated images of the brachial artery were acquired with Sonos 5000 (Philips) prior to inflation and 15 s before deflation to 1 min after deflation. Offline analysis was carried out to find out maximum post-deflation diameter and from these values absolute increase and the percentage increase in diameter were calculated.

2.7. Biochemical parameters

Lipid profile was estimated after 12 h of overnight fasting as per hospital protocol. Total cholesterol was estimated by cholesterol oxidase, esterase, peroxidase method. HDL cholesterol was by direct measurement using immune-inhibition. LDL cholesterol estimation was done by cholesterol oxidase, esterase, peroxidase method and the VLDL cholesterol was calculated. In our study, triglycerides were estimated by enzymatic end point method. Colorimetric method was used to estimate non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA).

Lipoprotein a (Lpa), apolipoprotein B, apolipoprotein A, and ultrasensitive reactive protein were estimated by immunoturbidometry.

Glycosylated hemoglobin was measured by HPLC.

2.8. Antioxidants-hemolysate preparation

Five clinically important antioxidants were estimated at different time intervals. After separation of the plasma, the blood cells were washed with 3 ml of cold normal saline (0.9% NaCl), centrifuged, and supernatant discarded. This was repeated for 2 more times. The cells were made up to 30 ml with ice cold distilled water and stored in refrigerator. All 5 parameters were estimated by photo metrical method from this hemolysate by allowing to react with corresponding reagents.

3. Results

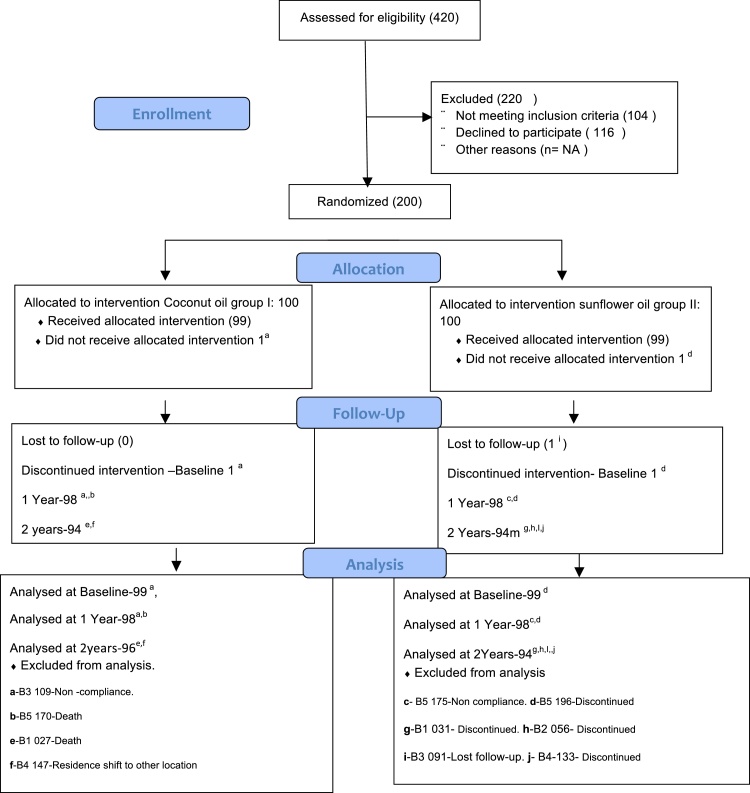

From August 2009 to April 2014, 200 patients were recruited (Fig. 1). Group I – Coconut oil, Group II – Sunflower oil.

Fig. 1.

Randomization, allocation, follow-up, and analysis.

As in any other CAD study, the male population was predominant. Among the conventional risk factors, the most common one was dyslipidemia (Table 2). Most of the patients in each group were asymptomatic and were leading active life style. Significant number of patients in each group 61.6% and 56.2% had undergone percutaneous revascularization while more than 20% were post-coronary artery bypass graft patients. Even though the two groups appear very much heterogeneous, statistically they are comparable.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients.

| Parameter | Group I | Group II | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 58.97 (SD – 8.44) | 58.97 (SD – 8.93) | 1 |

| Gender (%) | 93.9 (male) | 92.9 (male) | 1 |

| 6.1 (female) | 7.1 (female) | ||

| Hypertension (%) | 58.2 | 55.1 | 0.67 |

| Diabetes (%) | 53.1 | 60.2 | 0.31 |

| Dislipidemia (%) | 74.0 | 63.0 | 0.09 |

| Ex smoking (%) | 54.1 | 57.1 | 0.77 |

| Active lifestyle (%) | 96.9 | 87.8 | 0.29 |

| Asymptomatic cardiac status (%) | 93.9 | 93.9 | 0.24 |

| Positive stress test (%) | 18.4 | 15.3 | 0.7 |

| STEMI (%) | 49.0 | 49.0 | 1.0 |

| NSTE MI (%) | 11.2 | 9.2 | 0.81 |

| Occupation | |||

| Skilled (%) | 32.7 | 30.9 | 0.71 |

| Professional (%) | 13.3 | 17.5 | |

| Retired (%) | 54.1 | 51.5 | |

| Family history of CAD | |||

| In parents (%) | 24.5 | 17.3 | 0.3 |

| In siblings (%) | 8.2 | 14.3 | |

| In parents and siblings (%) | 18.4 | 14.3 | |

| Confirmation of CAD (%) | |||

| CAG | 53.1 | 53.1 | 0.49 |

| ECG | 2.0 | 1.0 | |

| Multi-modality | 44.9 | 45.9 | |

| Revascularization | |||

| PTCA | 61.6 | 56.2 | 0.13 |

| CABG | 20.4 | 22.4 | 0.86 |

The body mass index in both groups were comparable at the end of 2 years. The percentage body fat calculated by substituting the skin fold thickness into Siri equation in both groups was not different statistically (Table 3).

Table 3.

Anthropometric measurements.

| Group I |

Group II |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p Value |

| Weight (kg) | |||||

| Baseline | 63.61 | 8.51 | 64.51 | 8.43 | 0.44 |

| 1 Year | 63.88 | 8.74 | 64.53 | 8.68 | 0.60 |

| 2 Years | 64.23 | 8.78 | 64.80 | 9.00 | 0.65 |

| BMI | |||||

| Baseline | 25.06 | 6.00 | 24.38 | 2.99 | 0.32 |

| 1 Year | 24.60 | 3.13 | 24.39 | 3.10 | 0.63 |

| 2 Years | 24.72 | 3.07 | 24.54 | 3.07 | 0.68 |

| Waist hip ratio | |||||

| Baseline | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.07 | 0.89 |

| 1 Year | 0.95 | 0.04 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| 2 Years | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.05 | 0.37 |

| Percentage body fat | |||||

| Baseline | 18.15 | 4.05 | 18.59 | 4.32 | 0.46 |

| 1 Year | 18.48 | 3.81 | 18.39 | 4.64 | 0.88 |

| 2 Years | 17.48 | 2.91 | 17.39 | 3.62 | 0.77 |

Traditional lipid profile estimation (Table 4) carried out in both groups at baseline, 3 months, 1 year, and 2 years did not show statistically significant differences in both the groups.

Table 4.

Lipid profile.

| Group I |

Group II |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p Value |

| Total cholesterol, mg/100 ml | |||||

| Baseline | 149.81 | 29.92 | 146.79 | 26.55 | 0.45 |

| 3 Months | 151.19 | 30.15 | 143.43 | 30.22 | 0.07 |

| 1 Year | 144.58 | 30.92 | 139.80 | 33.75 | 0.30 |

| 2 Years | 149.28 | 28.57 | 151.63 | 44.54 | 0.66 |

| LDL, mg/100 ml | |||||

| Baseline | 90.29 | 24.38 | 86.10 | 19.62 | 0.18 |

| 3 Months | 89.31 | 24.75 | 84.12 | 22.16 | 0.12 |

| 1 Year | 91.02 | 20.66 | 87.56 | 25.31 | 0.29 |

| 2 Years | 91.04 | 21.82 | 89.62 | 28.91 | 0.70 |

| Triglycerides, mg/100 ml | |||||

| Baseline | 114.96 | 54.22 | 111.17 | 48.85 | 0.60 |

| 3 Months | 111.23 | 37.26 | 108.90 | 39.28 | 0.67 |

| 1 Year | 112.00 | 50.19 | 114.52 | 64.83 | 0.76 |

| 2 Years | 109.32 | 47.06 | 112.20 | 45.15 | 0.66 |

| HDL, mg/100 ml | |||||

| Baseline | 40.80 | 9.16 | 40.74 | 9.95 | 0.96 |

| 3 Months | 40.82 | 10.92 | 39.57 | 9.68 | 0.39 |

| 1 Year | 42.41 | 9.48 | 40.10 | 11.10 | 0.11 |

| 2 Years | 43.22 | 10.77 | 44.36 | 16.35 | 0.56 |

| VLDL, mg/100 ml | |||||

| Baseline | 21.82 | 8.00 | 23.27 | 16.76 | 0.44 |

| 3 Months | 22.31 | 7.43 | 21.61 | 7.74 | 0.52 |

| 1 Year | 21.27 | 9.58 | 22.43 | 15.41 | 0.44 |

| 2 Years | 21.77 | 9.37 | 22.53 | 9.72 | 0.58 |

| NEFA, nmol/L | |||||

| Baseline | 0.44 | 0.32 | 0.45 | 0.28 | 0.97 |

| 3 Months | 0.61 | 0.32 | 0.6 | 0.35 | 0.95 |

| 1 Year | 0.57 | 0.31 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0.01 |

| 2 Years | 0.58 | 0.35 | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.45 |

Lpa levels were 21.81 ± 21.89 and 25.13 ± 28.73 at the beginning of the study and at the end of the study, the values were 22.46 ± 20.24 and 30.64 ± 31.13 in Group I and in Group II, respectively. Even though statistically not significant, Lpa was slightly high in Group II (Table 5).

Table 5.

Carrier proteins.

| Group I |

Group II |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p Value |

| Lipoprotein a (Lpa), mg/100 ml | |||||

| Baseline | 21.81 | 21.89 | 25.13 | 28.73 | 0.28 |

| 1 Year | 24.63 | 25.08 | 28.91 | 33.33 | 0.31 |

| 2 Years | 22.46 | 20.24 | 30.64 | 31.13 | 0.03 |

| Apo B/A ratio | |||||

| Baseline | 0.538 | 0.234 | 0.545 | 0.284 | 0.850 |

| 1 Year | 0.585 | 0.236 | 0.577 | 0.303 | 0.840 |

| 2 Years | 0.635 | 0.394 | 0.640 | 0.380 | 0.925 |

The ratio of atherogenic and non-atherogenic lipoprotein in both study groups at baseline was in low risk group and did not show difference at 2 years.

FMD as surrogate marker of endothelial function was comparable at the end of the study in both groups (Table 6).

Table 6.

Flow-mediated vasodilatation. Median of absolute increase and percentage increase.

| Variables | Group I |

Group II |

p Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Median | Minimum | Maximum | n | Median | Minimum | Maximum | ||

| ABIN1 | 98 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 1.20 | 98 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 1.30 | 0.57 |

| PRIN1 | 98 | 7.02 | 0.24 | 27.27 | 98 | 7.07 | 0.00 | 34.21 | 0.58 |

| ABIN2 | 98 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.87 | 98 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.51 |

| PRIN2 | 98 | 5.70 | 0.00 | 25.40 | 98 | 5.47 | 0.00 | 30.84 | 0.49 |

| ABIN3 | 96 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.95 | 94 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 1.03 | 0.75 |

| PRIN3 | 96 | 6.82 | 0.24 | 29.69 | 94 | 6.85 | 0.00 | 30.30 | 0.72 |

ABIN – absolute increase, PRIN – percentage increase.

Five important antioxidants enzymes estimated in our study, which are related to the oxidative stress, remain comparable at baseline, 3 months, 1 year, and 2 years (Table 7).

Table 7.

Antioxidants.

| Group I |

Group II |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p Value |

| Lipidperoxidase [nmol/ml] | |||||

| Baseline | 0.139 | 0.070 | 0.148 | 0.104 | 0.508 |

| 3 Months | 0.120 | 0.036 | 0.124 | 0.038 | 0.509 |

| 1 Year | 0.146 | 0.134 | 0.160 | 0.179 | 0.542 |

| 2 Years | 0.150 | 0.132 | 0.128 | 0.042 | 0.119 |

| Glutathione reductase [nmol NADPH oxidase/m/mg protein] | |||||

| Baseline | 0.0040 | 0.0020 | 0.00392 | 0.0018 | 0.553 |

| 3 Months | 0.0044 | 0.0021 | 0.00454 | 0.0017 | 0.617 |

| 1 Year | 0.0051 | 0.00195 | 0.0047 | 0.0017 | 0.199 |

| 2 Years | 0.0050 | 0.0016 | 0.0049 | 0.0016 | 0.731 |

| Glutathione S transferase [nmol CDNB coagulate formed/mg protein/min] | |||||

| Baseline | 0.0017 | 0.00165 | 0.0019 | 0.0025 | 0.522 |

| 3 Months | 0.00196 | 0.00105 | 0.00280 | 0.0015 | 0.540 |

| 1 Year | 0.00269 | 0.0026 | 0.0027 | 0.0020 | 0.987 |

| 2 Years | 0.00285 | 0.0011 | 0.0028 | 0.0014 | 0.852 |

| Superoxide dismutase [U/mg hemoglobin] | |||||

| Baseline | 2 | 0.77 | 2.02 | 0.75 | 0.813 |

| 3 Months | 2.07 | 0.75 | 2.10 | 0.81 | 0.756 |

| 1 Year | 1.79 | 0.88 | 2.13 | 1.28 | 0.037 |

| 2 Years | 1.64 | 0.61 | 1.80 | 0.61 | 0.072 |

| Catalase [mmol H2O2 decomposed/mg protein/min] | |||||

| Baseline | 0.02091 | 0.04283 | 0.01854 | 0.01854 | 0.617 |

| 3 Months | 0.01534 | 0.01426 | 0.02005 | 0.0259 | 0.117 |

| 1 year | 0.01217 | 0.01609 | 0.01402 | 0.01786 | 0.459 |

| 2 years | 0.00619 | 0.01201 | 0.00459 | 0.00700 | 0.267 |

One of the inflammatory markers assessed in atherosclerotic CAD is ultra-sensitive C reactive. The anti-inflammatory response assessed by evaluating hCRP at the baseline and end of the study remains statistically comparable even though there is reduction in Group I which is statistically not significant (Table 8).

Table 8.

Anti-inflammatory markers.

| Group I |

Group II |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p Value |

| Ultra sensitive C-reactive protein [IU/L] | |||||

| Baseline | 1.5732 | 1.9016 | 1.289 | 1.65 | 0.265 |

| 2 Years | 1.23 | 1.59 | 1.43 | 1.72 | 0.411 |

Glycosylated hemoglobin as the marker for diabetic control was not influenced by either oil during 2-year study period (Table 9).

Table 9.

Glycemic control.

| Group I |

Group II |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p Value |

| HbAIc | |||||

| Baseline | 6.62 | 1.20 | 6.79 | 1.19 | 0.316 |

| 1 Year | 6.6 | 1.28 | 6.69 | 1.2 | 0.578 |

| 2 Years | 6.54 | 1.32 | 6.77 | 1.28 | 0.229 |

Out of 200 patients on standard medical treatment, 2 in each group underwent revascularization. Deaths in Group I were due to road traffic accidents (Table 10).

Table 10.

Cardiovascular events during 2 years.

| Group I | Group II | |

|---|---|---|

| Death | 2 | 0 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 0 |

| Stroke | 0 | 0 |

| Repeat revascularization | 2 | 2 |

All of our patients were on different types statins as prescribed at the time of CAD diagnosis. Those patients with lipid levels at ATP III level were only included in the study. Atorvastatin, simvastatin, and rosuvastatin were the three major groups of lipid lowering drugs and a small fraction of patients were on fibrates and nicotinic acid (Table 11).

Table 11.

Statins and dosage.

| Statin dosage | Group I |

Group II |

p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Median | Min–max | n | Median | Min–max | ||

| Visit 1 | |||||||

| Atrovastatin | 68 | 20 | 5–40 | 63 | 20 | 5–40 | 0.448 |

| Simvastatin | 12 | 10 | 5–20 | 16 | 10 | 5–40 | 0.391 |

| Rosuvastatin | 16 | 10 | 5–20 | 18 | 10 | 5–20 | 0.552 |

| Visit 2 | |||||||

| Atrovastatin | 64 | 20 | 5–60 | 62 | 10 | 5–60 | 0.632 |

| Simvastatin | 11 | 15 | 5–20 | 13 | 20 | 10–40 | 0.288 |

| Rosuvastatin | 18 | 10 | 5–20 | 22 | 10 | 5–20 | 0.376 |

| Visit 3 | |||||||

| Atrovastatin | 62 | 20 | 5–80 | 59 | 10 | 5–40 | 0.221 |

| Simvastatin | 10 | 10 | 5–20 | 10 | 15 | 10–40 | 0.402 |

| Rosuvastatin | 21 | 10 | 5–30 | 24 | 10 | 5–25 | 0.916 |

4. Discussion

Nothing has been discussed as much as role of ideal oil media in primary and secondary prevention of CAD.22, 23, 24 Concern regarding the oil media for cooking starts growing in those sustaining a cardiovascular event or after CAD diagnosis. This particular study was designed to address the effect of coconut oil and sunflower on cardiovascular risk factors in those diagnosed to have CAD. Atherosclerotic CAD prevalence is quite high in this densely populated state where coconut oil is used for cooking traditionally. Prescreening survey shows that >65% of these patients were using coconut oil. Even though it appears that the population is very heterogeneous in respect to the profile of CAD, treatment, and medications, statistically they are comparable (Table 1). About 90% of the population was on mixed diet. Dietary intervention in atherosclerosis is difficult for reasons such as longer duration for the impact to be evident, marinating the compliance till end of the study, and to balance other contributing factors. Reasons for the delay in the recruitment were due to: (1) patients decision to change over to a particular oil; (2) family acceptance to the need for special cooking; and (3) behavioral modification to ensure home eating. In dietary interventions, adherence to the particular diet and monitoring of the same is very important. In this study, the following effective and widely used tools25, 26, 27 were used to assess the compliance to the oil assigned: (a) 24 h recall, (b) 7 day recall, and (c) a diet dairy.

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

| No. | Section A: Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| 1 | Male/Female – 18 years of age or older |

| 2 | Clinical evidence of CAD with one of the following |

| (a) Significant CAD in at least one of the epicardial coronary arteries confirmed by angiography | |

| (b) Previous MI or Acute Coronary Syndrome (UA/NSTEMI) not <3-month duration | |

| (c) Objective evidence of myocardial ischemia (TMT, pharmacological stress test or radionuclide scan) with symptoms or on treatment | |

| (d) MDCT evidence of significant CAD | |

| (e) Pathological Q wave in ECG and or RWMA in Echo | |

| 3 | Have achieved target lipid Levels as per adult treatment panel III (ATP-III) guidelines and good glycemic control (HbA1c < 7 mg%) |

| 4 | Subjects willing to comply with all follow-up visits |

| 5 | Subjects signed and received copy of informed consent for trial |

| No. | Section B: Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| 1 | Untreated hypothyroidism, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus |

| 2 | Severe congestive heart failure (class III or IV according to NYHA, or pulmonary edema) at the time of enrollment |

| 3 | Pre-existing malabsorption syndrome |

| 4 | Dietary pattern/domestic dietetic environment unsuitable for trial design |

| 5 | Abnormal renal function with creatinine > 2.0 mg/dl and or creatinine clearance < 30 ml/m |

| 6 | Abnormal hepatic enzymes (SGOT/SGPT greater than 3 times the reference range) at entry |

Anthropometric measurements like BMI, waist hip ratio, and percentage body fat reflect the risk for atherosclerosis.28, 29 Abdominal obesity is quite common in this community that seems to be determined genetically but influenced by diet and exercise. In our study, these parameters remained comparable throughout the study (Table 3).

Lipids assessed at various intervals (baseline, 3 months, 12 months, and 24 months) show no statistically significant difference between both groups. Median chain saturated fatty acids in coconut oil do not seem to increase the lipids when compared with polyunsaturated fatty acids of sunflower oil when consumed along medication including statins. This is the real world scenario in this community with majority of patients continuing to use coconut oil even after being diagnosed to have atherosclerotic CAD. The primary objective of our study was to assess whether this traditional cooking oil media influence the CAD risk factors unfavorably in spite of medication. As the traditional lipid profile reflects only a part of atherogenic burden30 to assess the atherogenic versus non-atherogenic lipids, apolipoprotein B and A were evaluated in the study population. Even though apo B/A-1 ratio showed a progressive increase throughout the study, there was no statistically significant difference between both the arms throughout the study. As the apo B/A ratio is between 0.5 and 0.7 in this study, our population can be categorized into a moderate risk group as per the risk line based on the results from AMORIS and INTERHEART studies.31, 32 NEFA is an independent cardiovascular risk factor which predict cardiovascular events including sudden death.33 In these study groups at the end of 2 years, there was no statistically significant difference in NEFA indicating that the free circulating free fatty acids are not influenced by either oil. Lpa estimated in this study remains below the lower limit of the established levels of risk stratification.33 Even though determined genetically, there are reports indicating that the dietary and pharmacological intervention changes the profile of this pro-atherogenic component.34, 35 The present study did not show any effect on Lpa either by sunflower oil or coconut oil.

Oxidized LDL cholesterol promotes atherosclerosis in many ways.36 Free radicals are generated during the metabolism of substance like fatty acids. Antioxidants of clinical importance in cardiovascular diseases, which are scavengers37 of free radicals estimated at different time points in both arms, remained statistically comparable. The normal values of these enzymes are not well established in this particular population but we compared baseline level with enzymes levels at different time intervals to assess the status of redox potential.

Atherosclerosis is closely related to systemic inflammation. Various epidemiological studies have shown the association of increased CRP and cardiovascular disease.38, 39 One of the best indicators of systemic inflammations used in cardiovascular risk assessment is high-sensitive C-reactive protein.40 The baselines CRP in our study group indicates that this population is having an average risk as per AHA and CDC and none of the oil seems to influence it on long-term use.

Diabetic control seems to be one of the measures to arrest the progression of atherosclerosis.41 Our study patients seem to have tight control of diabetes as the baseline glycosylated hemoglobin levels were <7, probably due to regular follow-up and strict adherence to medication since being diagnosed to have CAD. Virgin coconut oil has shown to have beneficial effect in diabetes mellitus patients.42 Ordinary coconut oil and sunflower oil used for 2 years did not show any influence on the glycemic levels of the study subjects.

FMD is the surrogate indicator of endothelial functions which depends on many factors including the oxidative stress.43, 44 Ischemia-induced vasodilatation of brachial artery in our study utilized the compression of arm by sphygmomanometer. The absolute and percentage increase in diameter of brachial artery did not show statistically significant difference in both these groups. As there are no established normal values for this response in this population, we compared values at different time intervals with the baseline value.

In any dietary intervention of atherosclerosis, the hard end points like myocardial infarction, death, and stroke are of paramount importance. Two deaths in Group I were due to road traffic accidents. There was no myocardial infarction in either group during the study period. Repeat revascularization rate was 2% in each group which is not high compared to revascularization rate in other trials.

Statin is prescribed for all patients with established CAD, probably due to its pleomorphic effect irrespective of the level of cholesterol level. For the same reason, lipid modulating dietary interventions are possible only along with the statin therapy in CAD patients. Monitoring the level of lipids and the dose of statins to maintain the lipid level at the recommended level is only alternative in this real world scenario. The statin dose and the type of statin required to maintain the lipid level did not change during the 2 years of study period.

5. Statistical analysis

Mean and the standard deviation of all the measurable variables were calculated for patients in the two groups. To test the statistical significance of difference in mean values of all variables, Student's t-test was done. In case the sample size was comparatively smaller for certain variables, Wilcoxon rank sum test was done. For categorical variables to study their association with type of oil (Group I and Group II), statistical test done was chi-square test.

6. Conclusion

Coconut oil even though rich in saturated fatty acids in comparison to sunflower oil when used as cooking oil media over a period of 2 years did not change the lipid-related cardiovascular risk factors and events in those receiving standard medical care.

7. Limitations

(1) This dietary intervention population is very small to assess a community issue. (2) The outcome is likely to be influenced by medication. (3) 2 Years duration of dietary intervention may not be sufficient enough to commend on major cardiac events.

8. Future prospective

A long-term community-based/family-based prospective study in normal free living population is necessary to answer the cardiovascular effect of coconut oil, as there are no such data available. Also, it is necessary to evaluate the same in different ethnic population in Asia Pacific region where coconut oil is produced and used in large scale.

Funding

Coconut Development Board of India and Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi, India.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Stamler J., Wentworth D., Neaton J.D. Is relationship between serum cholesterol and risk of premature death from coronary heart disease continuous and graded? Findings in 356,222 primary screeners of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) JAMA. 1986;256:2823–2828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neaton J.D., Blackburn H., Jacobs D. Serum cholesterol level and mortality findings for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:1490–1500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd-Jones D.M., Wilson P.W., Larson M.G. Framingham risk score and prediction of lifetime risk for coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musunuru K. Atherogenic dyslipidemia: cardiovascular risk and dietary intervention. Lipids. 2010;45:907–914. doi: 10.1007/s11745-010-3408-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mensink R.P., Zock P.L., Kester A.D., Katan M.B. Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1146–1155. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial results II The relationship of reduction in incidence of coronary heart disease to cholesterol lowering. JAMA. 1984;251:365–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1349–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811053391902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease. The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robins S.J., Collins D., Wittes J.T. Relation of gemfibrozil treatment and lipid levels with major coronary events: VA-HIT: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1585–1591. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.12.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sever P.S., Poulter N.R., Dahlöf B. Reduction in cardiovascular events with atorvastatin in 2532 patients with type 2 diabetes: Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial–lipid-lowering arm (ASCOT-LLA) Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1151–1157. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keene D., Price C., Shun-Shin M.J., Francis D.P. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high-density lipoprotein targeted treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kutty V.R., Balakrishnan K.G., Jayasree A.K., Thomas J. Prevalence of coronary heart disease in the rural population of Thiruvananthapuram district, Kerala, India. Int J Cardiol. 1993;39:59–70. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(93)90297-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thankappan K.R., Shah B., Mathur P. Risk factor profile for chronic non-communicable diseases: results of a community-based study in Kerala, India. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:53–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bach A.C., Babayan V.K. Medium-chain triglycerides: an update. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36:950–962. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLany J.P., Windhauser M.M., Champagne C.M., Bray G.A. Differential oxidation of individual dietary fatty acids in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:905–911. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.4.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar P.D. The role of coconut and coconut oil in coronary heart disease in Kerala, south India. Trop Doctor. 1997;27:215–217. doi: 10.1177/004947559702700409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liau K.M., Lee Y.Y., Chen C.K., Rasool A.H. An open-label pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of virgin coconut oil in reducing visceral adiposity. ISRN Pharmacol. 2011;2011:949686. doi: 10.5402/2011/949686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feranil A.B., Duazo P.L., Kuzawa C.W., Adair L.S. Coconut oil is associated with a beneficial lipid profile in pre-menopausal women in the Philippines. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2011;20:190–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabitha P., Vaidyanathan K., Vasudevan D.M., Kamath P. Comparison of lipid profile and antioxidant enzymes among south Indian men consuming coconut oil and sunflower oil. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2009;24:76–81. doi: 10.1007/s12291-009-0013-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabitha P., Vasudevan D.M., Kamath P. Effect of high fat diet without cholesterol supplementation on oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in New Zealand white rabbits. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2010;17:213–218. doi: 10.5551/jat.2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palazhy S., Kamath P., Rajesh P.C., Vaidyanathan K., Nair S.K., Vasudevan D.M. Composition of plasma and atheromatous plaque among coronary artery disease subjects consuming coconut oil or sunflower oil as the cooking medium. J Am Coll Nutr. 2012;31:392–396. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2012.10720464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kastorini C.M., Milionis H.J., Esposito K., Giugliano D., Goudevenos J.A., Panagiotakos D.B. The effect of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome and its components a meta-analysis of 50 studies and 534,906 individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1299–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.073. [Medline] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nordmann A.J., Suter-Zimmermann K., Bucher H.C. Meta-analysis comparing mediterranean to low-fat diets for modification of cardiovascular risk factors. Am J Med. 2011;124:841–851. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.04.024. e2. [Medline] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kromhout D., Giltay E.J., Geleijnse J.M. n-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular events after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2015–2026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003603. [Medline] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raper N., Perloff B., Ingwersen L., Steinfeldt L., Anand J. An overview of USDA's dietary intake data system. J Food Compos Anal. 2004;17:545–555. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moshfegh A.J., Rhodes D.G., Baer D.J. The U.S. Department of Agriculture Automated Multiple-Pass Method reduces bias in the collection of energy intakes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:324–332. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hebert J.R., Ockene I.S., Hurley T.G., Luippold R., Well A.D., Harmatz M.G. Development and testing of a seven-day dietary recall. Dietary Assessment Working Group of the Worcester Area Trial for Counseling in Hyperlipidemia (WATCH) J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:925–937. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Labounty T.M., Gomez M.J., Achenbach S. Body mass index and the prevalence, severity, and risk of coronary artery disease: an international multicentre study of 13,874 patients. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14:456–463. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seidell J.C., Pérusse L., Després J.-P., Bouchard C. Waist and hip circumferences have independent and opposite effects on cardiovascular disease risk factors: the Quebec Family Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:315–321. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sniderman A.D., Furberg C.D., Keech A. Apolipoproteins versus lipids as indices of coronary risk and as targets for statin treatment. Lancet. 2003;361:777–778. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iqbal R., Anand S., Ounpuu S. Dietary patterns and the risk of acute myocardial infarction in 52 countries: results of the INTERHEART study. Circulation. 2008;118:1929–1937. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.738716. Nov 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holme I., Aastveit A.H., Hammar N., Jungner I., Walldius G. Relationships between lipoprotein components and risk of ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke in the Apolipoprotein MOrtality RISk study (AMORIS) J Intern Med. 2009;265:275–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pilz S., Scharnagl H., Tiran B. Elevated plasma free fatty acids predict sudden cardiac death: a 6.85-year follow-up of 3315 patients after coronary angiography. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2763–2769. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clevidence B.A., Judd J.T., Schaefer E.J. Plasma lipoprotein (a) levels in men and women consuming diets enriched in saturated, cis-, or trans-monounsaturated fatty acids. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:1657–1661. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.9.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carlson L.A., Hamsten A., Asplund A. Pronounced lowering of serum levels of lipoprotein Lp(a) in hyperlipidaemic subjects treated with nicotinic acid. J Intern Med. 1989;226:271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1989.tb01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koenig W., Karakas M., Zierer A. Oxidized LDL and the risk of coronary heart disease: results from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg Study. Clin Chem. 2011;57:1196–1200. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.165134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young I.S., Woodside J.V. Antioxidants in health and disease. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:176–186. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.3.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johann Auer M.D., Robert Berent M.D., Elisabeth Lassnig M.D., Bernd Eber M.D. C-reactive protein and coronary artery disease. Jpn Heart J. 2002;43:607–619. doi: 10.1536/jhj.43.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yayan J. Emerging families of biomarkers for coronary artery disease: inflammatory mediators. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2013;9:435–456. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S45704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rifai N., Ridker P.M. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein: a novel and promising marker of coronary heart disease. Clin Chem. 2001;47:403–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fox C.S., Sullivan L., D’agostino R.B., Wilson P.W.F. The significant effect of diabetes duration on coronary heart disease mortality. Diabetes Care. 2004;27 doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.3.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaarin K., Norliana M., Kamisah Y., Nursyafiza M., Qodriyah H.M.S. Potential role of virgin coconut oil in reducing cardiovascular risk factors. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2014;20:3399. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veerasamy M., Bagnall A., Neely D., Allen J., Sinclair H., Kunadian V. Endothelial dysfunction and coronary artery disease: a state of the art review. Cardiol Rev. 2015;23:119–129. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poredos P., Jezovnik M.K. Testing endothelial function and its clinical relevance. Atheroscler Thromb. 2013;20:1–8. doi: 10.5551/jat.14340. [Epub 2012 Sep 10] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]