Abstract

A mammalian brain contains numerous types of cells. Advances in neuroscience in the past decade allow us to identify and isolate neural cells of interest from mammalian brains. Recent developments in high-throughput technologies, such as microarrays and next-generation sequencing (NGS), provide detailed information on gene expression in pooled cells on a genomic scale. As a result, many novel genes have been found critical in cell type-specific transcriptional regulation. These differentially expressed genes can be used as molecular signatures, unique to a particular class of neural cells. Use of this gene expression-based approach can further differentiate neural cell types into subtypes, potentially linking some of them with neurological diseases. In this article, experimental techniques used to purify neural cells are described, followed by a review on recent microarray- or NGS-based transcriptomic studies of common neural cell types. The future prospects of cell type-specific research are also discussed.

Keywords: cell type-specific, transcriptomics, microarray, next-generation sequencing (NGS), mammalian, brain, Review

2. INTRODUCTION

The brain is one of the most complex and important organs in a mammal’s body. A typical mammalian brain contains 108 (mouse) to 1011 (human) neurons and even larger numbers of glia (1). It has been the subject of a great deal of research, due to its importance with respect to behavior, perception, thought, and emotion. It is also the root of a number of serious diseases, including dementia, epilepsy, strokes, headache disorders, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. The World Health Organization (WHO) published a report in 2007 estimating that up to 1 billion people, or one in six of the world’s population, suffer from neurological disorders (2). This indicates that these diseases pose a great threat to public health. Responding to this threat, the United States has launched the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative to develop new tools and technologies for deepening our understanding of the brain (3–5).

Neural tissues in mammals include a large number of cell types. Although much progress has been made in the development of techniques to identify common neural cell types, the total number of neural cell types and subtypes is still far from clear. As such, one of the priority research areas of the BRAIN Initiative is to differentiate neural cell types and determine their roles in health and disease (5). Successful implementation of the Initiative would facilitate a better understanding of various neurological diseases, aiding in their diagnosis and treatment.

High-throughput technologies, including microarrays (6–7) and next-generation sequencing (NGS) (8–9), have helped dissect numerous neurological diseases (reviewed in ref. 10–12) and allow brain functional annotations at different levels. For instance, at the level of brain regions (e.g., prefrontal area), several studies have provided a comprehensive atlas of gene expression across the brain (13–15). At the level of single cells, expression profiling of tens of thousands of genes (16–19) has been achieved using multiplex PCR (20). However, the brain-wide data are difficult to interpret because the information is not available for the localization of individual transcripts at the cellular level (21–22), whereas the single-cell methods have issues of increased false negatives and reduced reproducibility (23–24). Given these difficulties, understanding of gene expression at the cellular level mainly comes from pooled cells obtained by several techniques such as laser-capture microdissection (LCM) (25–27), fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (28–32), immunopanning (PAN) (32–34), and translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP) (35–38).

In this article, we will first provide an overview of common cell types in mammalian brains and of experimental techniques for cell purification and identification. Then, we will review recent microarray- and NGS-based studies on transcriptomics of specific neural cell type. The future prospects of cell type-specific studies are also discussed.

3. IDENTIFICATION and ISOLATION OF CELL-TYPE SPECIFIC POPULATIONS IN A MAMMALIAN BRAIN

3.1. Common neural cell types

A mammalian brain is made up of a large number of cell types that are vital to proper functioning of the central nervous system (CNS). Foremost among them is neuron, a primary vehicle for long-distance electrical communication and computation among cells in mammals (39). Neurons are interconnected cells, each possessing a large cell body (soma), as well as cell projections called dendrites and an axon. The dendrites are thin, branched projections that receive neurotransmitters from other neurons, while the axon is a long projection sending electrical signals to the next neuron. Neurons send signals among themselves by changing electrical potentials, which can spread along the axon of a neuron. The bulb-like end of the axon, termed axon terminal, is separated from the dendrites of the next neuron by a narrow space (synapse). When electrical signals travel to the axon terminal, neurotransmitters are released across synapse and bind post-synaptic receptors, stimulating receiving neurons to modulate electrical potentials and continue nerve impulse. Neurons are arguably the most important cell type in the body, enabling computations required for vital behaviors such as balance, communication, and the ability to learn and make decisions. Changes in the gene expression of neurons can lead to an over- or under-expression of important genes, which can radically change the overall topology of the CNS and lead to severe disorders. For example, the Parkinson’s disease is characterized by an accumulation of alpha-synuclein and a subsequent deficiency of dopamine in the brain as the dopamine-producing cells die (40). The Huntington’s disease is caused by the production and accumulation of mutant Huntingtin (Htt) proteins (41).

Glial cells are non-neuronal cells, including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia, which are smaller in size (compared with neurons) and vary in structure (42). Astrocytes are star-shaped cells with great structural complexity (43–45). Traditionally, astrocytes are considered to be ancillary, satellite cells that provide a physical support network to neurons, and regulate the environment so that neurons can function properly. As such, astrocytes maintain extracellular ion balance and pH homeostasis (46). They hold important stores of glycogen, providing surrounding cells with glucose as needed (47). Moreover, astrocytes interact with the synapses of neurons, and work to both produce and remove neurotransmitters and other compounds from the intercellular space (48). Recent studies have revealed new roles of astrocytes (49–52). First, astrocytes establish separate territories that define functional domains of a brain (49). Second, astrocytes can release neuroactive agents such as glutamate to modulate synaptic transmission (50). Third, astrocytes interact with neurons and endothelial cells to form higher-order gliovascular units, bridging neuronal and vascular structure to match local neural activity and blood flow (51). Currently, astrocytes are seen as an important communication element of the brain, and their dysfunction may lead to aberrations of neuronal circuitry that underlies several neurodevelopmental disorders such as the Rett syndrome (53) and the fragile X mental retardation (54) (reviewed in ref. 55–56).

Besides astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and microglia are two types of glial cells. The main function of oligodendrocytes is to produce and maintain myelin sheath which wraps around axons. Myelin helps to support and insulate axons in the CNS. Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) are precursors to oligodendrocytes and can also differentiate into neurons and astrocytes. Microglial cells are resident macrophages that provide the first line of immune defense in the CNS. Oligodendrocytes and microglial cells account for 75.6.% and 6.5.% of the cerebral cortex glia, respectively (57).

3.2. Experimental techniques to isolate and purify specific neural cell types

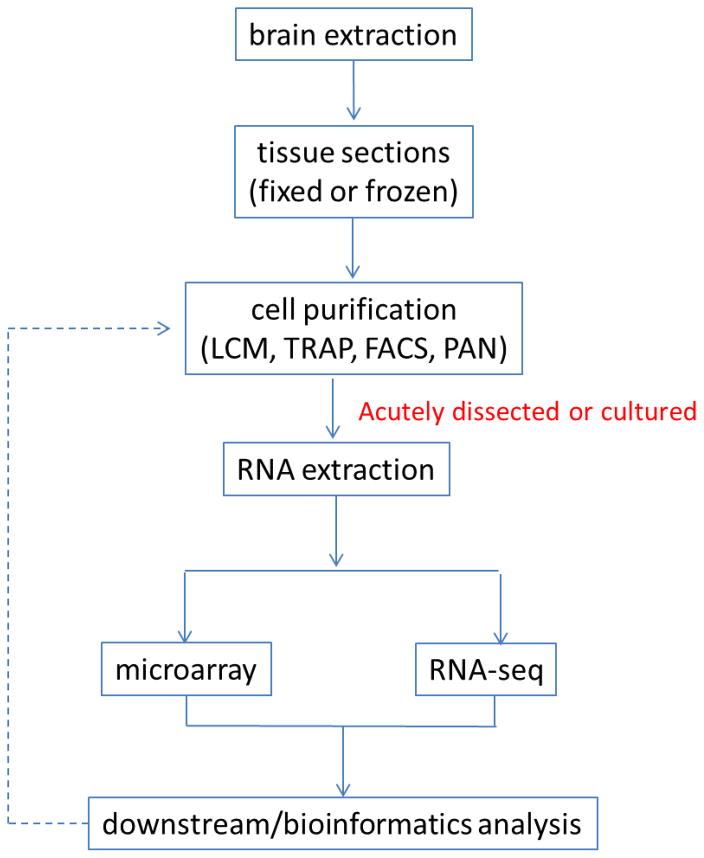

Cell type-specific transcriptomics require completion of several steps (Figure 1). First, brain tissues need to be isolated as fixed/frozen sections or live samples. Second, cells of interest need to be identified and collected. Third, RNA from the collected cells needs to be extracted and, if necessary, amplified. Fourth, relative mRNA expression levels need to be measured by microarray or RNA-seq. Finally, downstream analyses need to be performed using bioinformatics tools. In this section, we focus on the first two steps because tissue heterogeneity of a mammalian brain has been a major obstacle (Figure 1). A pure collection of neural cells is the key to profiling cell-type specific transcriptomes. It is worth noting that the problem of neural cell identification has been discussed (58–59). Cell type-specific markers and Cre-driver mouse lines are available to identify specific neural cell types (see online resources in ref. 60).

Figure 1.

Typical workflow of cell type-specific transcriptome profiling experiments. Cell-specific transcriptome profiling requires completing several steps such as brain sample collection, cell purification, RNA extraction, and RNA abundance measurement by microarray or RNA sequencing. At the last step, genes that are differentially expressed are identified by bioinformatic tools. If the protein products of these genes are directed to the surface of target cells, they can be used as cell markers. The cells presenting these proteins on the surface can be identified and purified by FACS and PAN. This process can undergo multiple iterations to differentiate a neural cell type into many subclasses.

Technically, specific neural cell types can be harvested by four methods: (1) laser-capture microdissection (LCM) or laser-directed microdissection (LDM) (25–27); (2) fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (28–32); (3) immunopanning (PAN) (32–34); and (4) translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP) (35–38). A quantitative analysis on cell type-specific microarray data has revealed that LCM and TRAP samples show significantly higher levels of contamination than FACS and PAN samples (60). Below, we provide a brief overview of these four methods.

LCM/LDM

LCM and LDM use a laser to isolate specific cell populations under a microscope from mounted thin-tissue sections that are either fixed or frozen. In LCM, a laser excises a small region (~7.5. μm) of a plastic membrane on the surface of tissue sections. Cells underneath adhere to the membrane upon cooling and are collected after the membrane is removed. One limitation of this method is that it does not allow users to extract a given cell by tracing its particular morphology. To overcome this limitation, LDM uses a much narrower ultraviolet laser (~0.5. μm), which allows users to make precise cuttings along the outline of target cells.

FACS

FACS requires that target cells are labelled by fluorophores. The fluorophores are typically attached to antibodies that recognize a target feature on the cells. Based on the specific light scattering and fluorescent characteristics of each cell, FACS can sort a heterogeneous mixture of a cell population into subgroups that may belong to specific cell types. In FACS, the live, acutely-dissected brain tissue is digested in a protease solution with artificial CSF (ACSF), which keeps dissociated cells in a healthy condition. One main advantage of the FACS method is that it can sort a large number of cells in a high-throughput manner.

PAN

PAN relies on antibodies against specific proteins on the surface of target cells, not fluorescent signals. Panning plates are first coated with antibodies, and dissociated cells are then placed in the plates for 30 minutes to 1 hour, allowing target cells to bind the antibodies. The plates are then washed to collect the cells of interest. Multiple iterations of plating and antibody interactions may be required, which may be more time-consuming than other techniques.

TRAP

TRAP uses special transgenic mice with restricted cell populations in the CNS. TRAP harvests RNA on labelled polysomes directly from tissue homogenates. Only ribosome-associated mRNA rather than the full population of transcribed RNA is detected. As a result, the noncoding RNAs that play an important role in gene regulation are discarded. Since tissue homogenates are used for analysis, TRAP samples often have contamination, as shown by previous studies (61).

4. CELL TYPE-SPECIFIC TRANSCRIPTOME PROFILING

Expression profiling of acutely-isolated cells

Microarrays have been used to analyze the functional genomics of different cell types acutely purified from the brain (Table 1). One of the first examples came from Dugas et al. (62) who compared gene expression in the oligodendrocytes (OLs) generated from cultured oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) in vitro and the OLs isolated acutely from animal brains. The OLs and OPCs were purified by PAN. Dugas et al. (62) found that OL differentiation occurs in at least two sequential stages, the early stage and the late stage, which are characterized by different expression patterns of transcription factors and myelin genes. Genes encoding cytoskeletal proteins are up-regulated during the OL differentiation. These findings were confirmed later by Cahoy et al. (32) who found that multiple signaling pathways including actin cytoskeleton signaling are enriched in the OLs. A separate study showed that a miRNA species, miR-9, is important for the OL differentiation and its expression inversely correlates with the expression of peripheral myelin protein PMP22 (64). This finding highlights the importance of miRNAs in neuronal cell specification (75).

Table 1.

Cell type-specific transcriptomic studies in mammalian brain

| Cell preparation | Purification | Cell type | Exp. method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| acutely purified | PAN | oligodendrocyte | Microarray | 62 |

| acutely purified | LDM | neuron | Microarray | 26 |

| acutely purified | FACS | astrocyte | Microarray | 63 |

| acutely purified | TRAP | 24 cell types | Microarray | 35 |

| acutely purified | FACS, PAN | astrocyte, neuron, oligodendrocyte | Microarray | 32 |

| acutely purified | FACS | oligodendrocyte | Microarray | 64 |

| acutely purified | FACS | endothelial cell | Microarray | 65 |

| acutely purified | FACS | 5HT Neuron | Microarray | 66 |

| acutely purified | LCM | purkinje cell | Microarray | 67 |

| acutely purified | FACS | neural stem cell | Microarray | 68 |

| acutely purified | FACS | microglia | Microarray | 69 |

| acutely purified | FACS | astrocyte, microglia | Microarray | 70 |

| acutely purified | FACS | microglia | RNA-seq | 71 |

| acutely purified | LCM | neuron | RNA-seq | 72 |

| acutely purified | FACS, PAN | astrocyte, neuron, oligodendrocyte, endothelial cell, microglia, pericyte | RNA-seq | 73 |

| cultured | oligodendrocyte | Microarray | 62 | |

| cultured | astroglia | Microarray | 32 | |

| cultured | microglia | Microarray | 69 | |

| cultured | neuron | RNA-seq | 74 | |

| cultured | astrocyte, neuron, oligodendrocyte progenitor cell | RNA-seq | 92 |

Transcriptomic analyses of pooled neurons have shown that neurons have an elevated expression of genes involved in glycolysis and oxidative metabolism (63). The enzymes in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle are expressed at low levels. Several pathways involved in calcium signaling, axonal guidance signaling, glutamate receptor signaling, and GABA receptor signaling are enriched in neurons (32). Further studies on transcriptomes of rostral and caudal serotonin neurons provide evidence for the complexity of gene regulatory networks in different types of neurons (66). In particular, hundreds of transcripts are differentially expressed in rostral and caudal serotonin neurons, in which a homeodomain code seems to play a key role in differentiating these two types of neurons. Finally, gene expression profiling of neural stem cells (NSCs) has revealed that the growth factor insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) is expressed at high levels, which suggests that IGF2 plays an important role in adult neurogenesis (68).

Expression profiling on isolated astrocytes has uncovered that the enzymes in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle are expressed at higher levels than in neurons (61). Not surprisingly, the TCA cycle is found to be one of the metabolic pathways enriched in astrocytes (32). Moreover, the Notch signaling pathway is one of the top pathways enriched in astrocytes. Although Notch signaling has been suggested to play a role in differentiating neural progenitor cells into astrocytes, these findings indicate that Notch signaling may be required for maintaining astrocyte fate, preventing them from reverting to undifferentiated states (76). Note that gene expression patterns in astrocytes vary as a function of age: young astrocytes have high expression levels of genes involved in neuronal differentiation and hemoglobin synthesis, whereas aged astrocytes are characterized by increased inflammatory phenotypes and zinc ion binding (70).

Transcriptomic analyses of purified microglia reveal distinct gene expression patterns for young and aged microglia. Young microglia cells are characterized with increased transcript levels of chemokines such as Ccl2 and Ccl7 (70). These chemokines have been linked to differentiation and maturation of neurons (77). By contrast, genes within the tumor necrosis factor-ligand family, such as Tnfsf12 and Tnfsf13b, are up-regulated in aged microglia (70, 78–79). Microarray analyses on acutely-isolated brain endothelial cells (65) and Purkinje cells (67) have also provided cell type-specific gene signatures.

The aforementioned gene expression profiling experiments are performed by microarrays. While microarray-based methods have been used for many years, these methods have numerous limitations. For example, microarrays can have cross-hybridization artifacts, detection difficulties due to the dye, and can be very limited in terms of alternative splicing (80). In recent years, next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become a popular tool for accurate, reproducible measurements of transcriptomics. This technique can provide sequences of all RNA molecules present within a cell, allowing for an accurate counting of different RNA species. RNA samples can be prepared from pooled cells, brain regions, or even individual cells (81).

Due to its unique ability to uncover details on both the expression level and isoform diversity, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has been used to identify gene expression signatures and gene splicing in acutely-isolated neurons (72) and microglia (71). Recently, Zhang et al. (73) used RNA-seq to generate transcriptome databases for eight cell types including neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocyte precursor cells, newly formed oligodendrocytes, myelinating oligodendrocytes, microglia, endothelial cells, and pericytes from the mouse cerebral cortex. Remarkably, they found that the majority (~92%) of differentially expressed genes identified by microarray (32) are found by RNA-seq. As expected, the authors uncovered well-known cell type-specific markers, e.g., Aqp4 and Aldh1l1 for astrocytes, and Dlx1 and Stmn2 for neurons (32, 62, 65, 69, 71). Moreover, they have detected a large number of new genes with previously unknown cell type-specific distributions, highlighting the improved sensitivity of RNA-seq over microarrays. For example, the autism and schizophrenia-associated gene Tspan7 is enriched in astrocytes, whereas a gene encoding a novel transmembrane protein Tmem59l is enriched in neurons. These data have provided a set of cell type-specific transcription factors that are important for cell fate determination and differentiation. These databases also allow the detection of alternative splicing events in glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the brain. One important finding is that PKM2, the gene encoding the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase, has unique splicing forms in neurons and astrocytes. This may explain how neurons and astrocytes differ in their ability to regulate the glycolytic flux and lactate generation (82–86).

Expression profiling of cultured cells

Before the development of technologies like LCM/LDM, FACS, PAN, and TRAP, primary cultures of neural cells such as astroglia (87) had served as an in vitro proxy for studying in vivo astrocytes. These cultured astrocytes have phenotypic characteristics that are significantly different from their in situ counterparts. For instance, astrocytes in situ are highly polarized cells, with distinct sets of processes that project to either synapses or vascular walls (88–89). Cultured astrocytes, however, appear non-polarized with an epithelioid-like shape in the cultures. Several studies have found that genes that are induced in the cultured astrocytes are not necessarily expressed in vivo, suggesting that cultured astroglia do not represent the same cell type as in vivo astrocytes (32, 90). This is not true however for oligodendrocytes and retinal ganglion cells (see below), suggesting that at least for certain neural cell types, cells cultured in vitro mimic those in vivo. Understanding the differences in gene expression between cells grown in vitro and those acutely purified from animal brains is critical for making the right decision on what cells can be used under which situation.

Dugas et al. have compared the transcriptomic profiles between cultured OLs and acutely-purified OLs, and found a remarkable similarity in gene expression between the two groups (62). This result indicates that normal OL differentiation can take place in the absence of heterologous cell-cell interactions. This similarity between cultured and acutely-isolated cells is also observed for retinal ganglion cells (91), but not for astrocytes (32) and microglia (69).

Recently, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of transcriptomes in cultured neurons, astrocytes and OPCs through RNA-seq, and identified cell-specific marker genes and characteristic pathways that are known for these cell types (92). We compared our RNA-seq data with those from Zhang et al. (73) and found a number of genes are differentially expressed in cultured cells compared to acutely isolated cells. We conclude that the findings obtained from cells cultured in vitro should not be extrapolated to cells in vivo, especially when targeting genes or pathways associated with neurological diseases.

5. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

During the past decade, various types of neural cells have been identified and isolated by experimental techniques such as LCM, FACS, PAN, and TRAP. Most of these techniques depend on antibodies recognizing a small number of cell type-specific surface markers. Transcriptomic studies on the isolated cells of interest (Table 1) have identified numerous cell type-specific genes and pathways. Some of these genes can be used as molecular signatures to identify subclasses of neural cells. That is, if the protein products of these genes are directed to cell surface, they can be recognized by antibodies. A subclass of cells with these surface proteins can be isolated by FACS or PAN. This gene expression-based method allows us to identify many subtypes of a given neural population. This information may be very useful if we intend to link a neurological disease with a particular class of neurons. This gene expression-based classification of neural cells is a promising approach for cell type-specific research in the future.

Most cell type-specific studies so far are focused on transcriptomics, aiming to elucidate gene expression patterns of a given cell type. Few studies are dedicated to epigenomics. Analyses of genome-wide chromatin organization, including histone modification and DNA methylation, may shed new light on: (1) novel cell type-specific markers, (2) chromatin accessibility during differentiation, and (3) mechanisms underlying differential gene expression observed.

Finally, most studies to date have used cells from normal subjects. It would be more valuable to extend cell type-specific research to disease models. Understanding gene regulatory networks in the cell types responsible for a neurological disease would help to uncover the genetic and metabolic basis of this disease, which in turn, could open up new ways to diagnosis and new treatments of the disease. It would be an invaluable contribution to the BRAIN Initiative from which millions of people would benefit.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Start-Up fund of the Rochester Institute of Technology and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences under Award Number R15GM116102 (F.C)

Abbreviations

- LCM

laser-capture microdissection

- LDM

laser-directed microdissection

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- PAN

immunopanning

- TRAP

translating ribosome affinity purification

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

References

- 1.Rowitch David, Kriegstein Arnold. Developmental genetics of vertebrate glia-cell specification. Nature. 2010;468:214–222. doi: 10.1038/nature09611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Neurological disorders: public health challenges. WHO press; Geneva, Switzerland: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kandel Eric, Markram Henry, Matthews Paul, Yuste Rafael, Koch Christof. Neuroscience thinks big (and collaboratively) Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;14:659–664. doi: 10.1038/nrn3578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devor Anna, Bandettini Peter, Boas David, Bower James, Buxton Richard, Cohen Lawrence, Dale Anders, Einevoll Gaute, Fox Peter, Franceschini Maria, Friston Karl, Fujimoto James, Geyer Mark, Greenberg Joel, Halgren Eric, Hamalainen Matti, Helmchen Fritjof, Hyman Bradley, Jasanoff Alan, Jernigan Terry, Lo Eng, Magistretti Pierre, Mandeville Joseph, Masliah Eliezer, Mitra Partha, Mobley William, Moskowitz Michael, Nimmerjahn Axel, Reynolds John, Rosen Bruce, Salzberg Brian, Schaffer Chris, Silva Gabriel, So Peter, Spitzer Nicholas, Tootell Roger, Van Essen David, Vanduffel Wim, Vinogradov Sergei, Wald Lawrence, Wang Lihong, Weber Bruno, Yodh Arjun. The challenge of connecting the dots in the B.R.A.I.N. Neuron. 2014;80:270–274. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jorgenson Lyric, Newsome William, Anderson David, Bargmann Cornelia, Brown Emery, Deisseroth Karl, Donoghue John, Hudson Kathy, Ling Geoffrey, MacLeish Peter, Marder Eve, Normann Richard, Sanes Joshua, Schnitzer Mark, Sejnowski Terrence, Tank David, Tsien Roger, Ugurbil Kamil, Wingfield John. The BRAIN initiative: developing technology to catalyst neuroscience discovery. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2015;370:20140164. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schena Mark, Shalon Dari, Davis Ronald, Brown Patrick. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science. 1995;270:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lashkari Deval, DeRisi Joseph, McCusker John, Namath Allen, Gentile Cristl, Hwang Seung, Brown Patrick, Davis Ronald. Yeast microarrays for genome wide parallel genetic and gene expression analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13057–13062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner Sydney, Johnson Maria, Bridgham John, Golda George, Lloyd David, Johnson Davida, Luo Shujun, McCurdy Sarah, Foy Michael, Ewan Mark, Roth Rithy, George Dave, Eletr Sam, Albrecht Glenn, Vermaas Eric, Williams Steven, Moon Keith, Burcham Timothy, Pallas Michael, DuBridge Robert, Kirchner James, Fearon Karen, Mao Jen, Corcoran Kevin. Gene expression analysis by massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) on microbead arrays. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:630–634. doi: 10.1038/76469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuster Stephan. Next-generation sequencing transforms today’s biology. Nat Methods. 2008;5:16–18. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bras Jose, Guerreiro Rita, Hardy John. Use of next-generation sequencing and other whole-genome strategies to dissect neurological disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:453–464. doi: 10.1038/nrn3271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foo Jia-Nee, Liu Jian-Jun, Tan Eng-King. Whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing in neurological diseases. Nat Rev Neurology. 2012;8:508–517. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang Teng, Tan Meng-Shan, Tan Lan, Yu Jin-Tai. Application of next-generation sequencing technologies in neurology. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2:125. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.11.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang Hyo, Kawasawa Yuka, Cheng Feng, Zhu Ying, Xu Xuming, Li Mingfeng, Sousa Andre, Pletikos Mihovil, Meyer Kyle, Sedmak Goran, Guennel Tobias, Shin Yurae, Johnson Matthew, Krsnik Zeljka, Mayer Simone, Fertuzinhos Sofia, Umlauf Sheila, Lisgo Steven, Vortmeyer Alexander, Weinberger Daniel, Mane Shrikant, Hyde Thomas, Huttner Anita, Reimers Mark, Kleinman Joel, Sestan Nenad. Spatio-temporal transcriptome of the human brain. Nature. 2011;478:483–489. doi: 10.1038/nature10523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlo Colantuoni C, Kipska Barbara, Ye Tianzhang, Hyde Thomas, Tao Ran, Leek Jeffrey, Colantuoni Elizabeth, Elkahloun Abdel, Herman Mary, Weinberger Daniel, Kleinman Joel. Temporal dynamics and genetic comtrol of transcriptional in the human prefrontal cortex. Nature. 2011;478:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawrylycz Michael, Lein Ed, Guillozet-Bongaarts Angela, Shen Elain, Ng Lydia, Miller Jeremy, van de Lagemaat Louie, Smith Kimberly, Ebbert Amanda, Riley Zackery, Abajian Chris, Beckmann Christian, Bernard Amy, Bertagnolli Darren, Boe Andrew, Cartagena Preston, Chakravarty Mallar, Chapin Mike, Chong Jimmy, Dalley Rachel, Daly Barry, Dang Chinh, Datta Suvro, Dee Nick, Dolbeare Tim, Faber Vance, Feng David, Fowler David, Goldy Jeff, Gregor Benjamin, Haradon Zeb, Haynor David, Hohmann John, Horvath Steve, Howard Robert, Jeromin Andreas, Jochim Jayson, Kinnunen Marty, Lau Christopher, Lazarz Evan, Lee Changkyu, Lemon Tracy, Li Ling, Li Yang, Morris John, Overly Caroline, Parker Patrick, Parry Sheana, Redding Melissa, Royall Joshua, Schulkin Jay, Sequeira Pedro, Slaughterbeck Clifford, Smith Simon, Sodt Andy, Sunkin Susan, Swanson Beryl, Vawter Marquis, Williams Derric, Wohnoutka Paul, Zielke Ronald, Geschwind Daniel, Hof Patrick, Smith Stephen, Koch Christof, Grant Seth, Jones Allan. An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain transcriptome. Nature. 2012;489:391–396. doi: 10.1038/nature11405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurimoto Kazuki, Saitou Mitinori. Single-cell cDNA microarray profiling of complex biological processes of differentiation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozsolak Fatih, Goren Alon, Gymrek Melissa, Guttman Mitchell, Regev Aviv, Bernstein Bradley, Milos Patrice. Digital transcriptome profiling from attomole-level RNA samples. Genome Res. 2010;20:519–525. doi: 10.1101/gr.102129.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozsolak Fatih, Ting David, Wittner Ben, Brannigan Brian, Paul Suchismita, Bardeesy Nabeel, Ramaswamy Sridhar, Milos Patrice, Haber Daniel. Amplification-free digital gene expression profiling from minute cell quantities. Nat Methods. 2010;7:619–621. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subkhankulova Tatiana, Yano Kojiro, Robinson Hugh, Kivesey Frederick. Grouping and classifying electrophysiologically-defined classes of neocortical neurons by single cell, whole-genome expression profiling. Front Mol Neurosci. 2010;3:10. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2010.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toledo-Rodriguez Maria, Blumenfeld Barak, Wu Caizhi, Luo Junyi, Attali Bernard, Goodman Philip, Markram Henry. Correlation maps allow neuronal electrical properties to be predicted from single-cell gene expression profiles in rat neocortex. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:1310–1327. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zirlinger Mariela, Kreiman Gabriel, Anderson David. Amygdala-enriched genes identified by microarray technology are restricted to specific amygdaloid subnuclei. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5270–5275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091094698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lein Ed, Zhao Xinyu, Gage Fred. Defining a molecular atlas of the hippocampus using DNA microarrays and high-throughput in situ hybridization. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3879–3889. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4710-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raj Arjun, van Oudenaarden Alexander. Single-molecule approaches to stochastic gene expression. Annu Rev Biophys. 2009;38:255–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janes Kevin, Wang Chun-Chao, Holmberg Karin, Cabral Kristin, Brugge Joan. Identifying single-cell molecular programs by stochastic profiling. Nat Methods. 2010;7:311–317. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung Chee, Seo Hyemyung, Sonntag Kai, Brooks Andrews, Lin Ling, Isacson Ole. Cell type-specific gene expression of midbrain dopaminergic neurons reveals molecules involved in their vulnerability and protection. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1709–1725. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossner Moritz, Hirrlinger Johannes, Wichert Sven, Boehm Christine, Newrzella Dieter, Hiemisch Holger, Eisenhardt Gisela, Stuenkel Carolin, vonAhsen Oliver, Nave Klaus-Armin. Global transcriptome analysis of genetically identified neurons in the adult cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9956–9966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0468-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pietersen Charmaine, Lim Maribel, Woo Tsung-Ung. Obtaining high quality RNA from single cell populations in human postmortem brain tissue. J Vis Exp. 2009;30:1444. doi: 10.3791/1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arlotta Paola, Molyneaux Bradley, Jinhui Chen, Inoue Jun, Kominami Ryo, Macklis Jeffrey. Neuronal subtype-specific genes that control cortico-spinal motor neuron development in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45:207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lobo Mary, Karsten Stanislav, Gray Michella, Geschwind Daniel, Yang William. FACS-array profiling of striatal projection neuron subtypes in juvenile and adult mouse brains. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:443–452. doi: 10.1038/nn1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marsh Eric, Minarcik Jennifer, Campbell Kenneth, Brooks-Kayal Amy, Golden Jeffrey. FACS-array gene expression analysis during early development of mouse telencephalic interneurons. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68:434–445. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molyneaux Bradley, Arlotta Paola, Fame Ryann, MacDonald Jessica, MacQuarrie Kyle, Macklis Jeffrey. Novel subtype-specific genes identify distinct subpopulations of callosal projection neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12343–12354. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6108-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cahoy John, Emery Ben, Kaushal Amit, Foo Lynette, Zamanian Jennifer, Christopherson Karen, Wang Yi, Lubischer Jane, Krieg Paul, Krupenko Sergey, Thompson Wesley, Barres Ben. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. J Neurosci. 2008;28:264–278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barres Barbara, Silverstein Bruce, Corey David, Chun Linda. Immunological, morphological, and electrophysiological variation among retinal ganglion cells purified by panning. Neuron. 1988;1:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barres Barbara, Hart Ian, Coles Harriet, Burne Julia, Voyvodic James, Richardson William, Raff Martin. Cell death and control of cell survival in the oligodendrocyte lineage. Cell. 1992;70:1–46. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90531-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doyle Joseph, Dougherty Joseph, Heiman Myriam, Schmidt Eric, Stevens Tanya, Ma Guojun, Bupp Sujata, Shrestha Prerana, Shah Rajiv, Doughty Martin, Gong Shiaoching, Greengard Paul, Heintz Nathaniel. Application of a translational profiling approach for the comparative analysis of CNS cell types. Cell. 2008;135:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heiman Myriam, Schaefer Anne, Gong Shiaoching, Peterson Jayms, Day Michelle, Ramsey Keri, Suarez-Farinas Mayte, Schwarz Cordelia, Stephan Dietrich, Surmeier James, Greengard Paul, Heintz Nathaniel. A translational profiling approach for the molecular characterization of CNS cell types. Cell. 2008;135:738–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanz Elisenda, Yang Linghai, Su Thomas, Morris David, McKnight Stanley, Amieux Paul. Cell-type-specific isolation of ribosome-associated mRNA from complex tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13939–13944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907143106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dougherty Joseph, Schmidt Eric, Nakajima Miho, Heintz Nathaniel. Analytical approaches to RNA profiling data for the identification of genes enriched in specific cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4218–4230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forrest Michael. Intracellular calcium dynamics permit a Purkinje neuron model to perform toggle and gain computations upon it inputs. Front Comput Neurosci. 2014;8:86. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2014.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shulman Joshua, De Jager Philip, Feany Mel. Parkinson’s disease: genetics and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:193–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker Francis. Huntington’s disease. Lancet. 2007;369:218–228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jessen Kristjan, Mirsky Rhona. Glial cells in the enteric nervous system contain glial fibrillary acidic protein. Nature. 1980;286:736–737. doi: 10.1038/286736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raff Martin, Abney Erika, Cohen Jim, Lindsay Ronald, Noble Mark. Two types of astrocytes in cultures of developing rat white matter: differences in morphology, surface gangliosides, and growth characteristics. J Neurosci. 1983;3:1289–1300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-06-01289.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yong Voon, Yong Fiona, Olivier Andre, Robitaille Yves, AnTel Jack. Morphologic heterogeneity of human adult astrocytes in culture: correlation with HLA-DR expression. J Neurosci Res. 1990;27:678–688. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490270428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bailey Mary, Shipley Michael. Astrocyte subtypes in the rat olfactory bulb: morphological heterogeneity and differential laminar distribution. J Comp Neurol. 1993;328:501–526. doi: 10.1002/cne.903280405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simard Marie, Nedergaard Maiken. The neurobiology of glia in the context of water and ion homeostasis. Neurosci. 2004;129:877–896. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dringen Ralf, Gebhardt Rolf, Hamprecht Bernd. Glycogen in astrocytes: possible function as lactate supply for neighboring cells. Brain Res. 1993;623:208–214. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91429-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newman Eric. New roles for astrocytes: regulation of synaptic transmission. Trends Neurosci. 2003;10:536–542. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nedergaard Maiken, Ransom Bruce, Goldman Steven. New roles for astrocytes: redefining the functional architecture of the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2003;10:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barres Ben. The mystery and magic of glia: a perspective on their roles in health and disease. Neuron. 2008;60:430–440. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takano Takahiro, Tian Guo-Feng, Peng Weiguo, Lou Nanhong, Libionka Witold, Han Xiaoning, Nedergaard Maiken. Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:260–267. doi: 10.1038/nn1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eroglu Cagla, Barres Ben. Regulation of synaptic connectivity by glia. Nature. 2010;468:223–231. doi: 10.1038/nature09612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ballas Nurit, Lioy Daniel, Grunseich Christopher, Mandel Gail. Non-cell autonomous influence of MeCP2-deficient glia on neuronal dendritic morphology. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:311–317. doi: 10.1038/nn.2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jacobs Shelley, Doering Laurie. Astrocytes prevent abnormal neuronal development in the fragile X mouse. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4508–4514. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5027-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Molofsky Anna, Krenick Robert, Ullian Erik, Tsai Hui-hsin, Deneen Benjamin, Richardson William, Barres Ben, Rowitch David. Astrocytes and disease: a neurodevelopmental perspective. Genes Dev. 2012;26:891–907. doi: 10.1101/gad.188326.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verkhratsky Alexei, Sofroniew Michael, Messing Albee, deLanerolle Nihal, Rempe David, Rodriguez Jose, Nedergaard Maiken. Neurological diseases as primary gliopathies: a reassessment of neurocentrism. ASN Neuro. 2012;4:e00082. doi: 10.1042/AN20120010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pelvig Dorte, Pakkenberg Henning, Stark Anette, Pakkenberg Bente. Neocortical glial cell numbers in human brains. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:1754–1762. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miyoshi Goichi, Fishell Gord. Directing neuron-specific transgene expression in the mouse CNS. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:577–584. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuhlman Sandra, Huang Josh. High-resolution labeling and functional manipulation of specific neuron types in mouse brain by Cre-activated viral gene expression. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Okaty Benjamin, Sugino Ken, Nelson Sacha. Cell type-specific transcriptomics in the brain. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6939–6943. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0626-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Okaty Benjamin, Sugino Ken, Nelson Sacha. A quantitative comparison of cell-type-specific microarray gene expression profiling methods in the mouse brain. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dugas Jason, Tai Yu-chuan, Speed Terence, Ngai John, Barres Ben. Functional genomic analysis of oligodendrocyte differentiation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10967–10983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2572-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lovatt Ditte, Sonnewald Ursula, Waagepetersen Helle, Schousboe Arne, He Wei, Lin Jane, Han Xiaoning, Takano Takahiro, Wang Su, Sim Fraser, Goldman Steven, Nedergaard Maiken. The transcriptome and metabolic gene signature of protoplasmic astrocytes in the adult murine cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12255–12266. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3404-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lau Pierre, Verrier Jonathan, Nielsen Joseph, Johnson Kory, Notterpek Lucia, Hudson Lynn. Identification of dynamically regulated microRNA and mRNA networks in developing oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11720–11730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1932-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Daneman Richard, Zhou Lu, Agalliu Dritan, Cahoy John, Kaushal Amit, Barres Ben. The mouse blood-brain barrier transcriptome: a new resource for understanding the development and function of brain endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wylie Christi, Hendricks Timothy, Zhang Bing, Wang Lily, Lu Pengcheng, Leahy Patrick, Fox Stephanie, Maeno Hiroshi, Deneris Evan. Distinct transcriptomes define rostral and caudal serotonin neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:670–684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4656-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Friedrich Bernd, Euler Philipp, Ziegler Ruhtraut, Kuhn Alexandre, Landwehrmeyer Bernhard, Luthi-Carter Ruth, Weiller Cornelius, Hellwig Sabine, Zucker Birgit. Comparative analyses of Purkinje cell gene expression profiles reveal shared molecular abnormalities in models of different polyglutamine diseases. Brain Res. 2012;1481:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bracko Oliver, Singer Tatjana, Aigner Stefan, Knobloch Marlen, Winner Beate, Ray Jasodhara, Clemenson Gregory, Jr, Suh Hoonkyo, Couillard-Despres Sebastien, Aigner Ludwig, Gage Fred, Jessberger Sebastian. Gene expression profiling of neural stem cells and their neuronal progeny reveals IGF2 as a regulator of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3376–3387. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4248-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beutner Clara, Linnartz-Gerlach Bettina, Schmidt Susanne, Beyer Marc, Mallmann Michael, Staratschek-Jox Andrea, Schultze Joachim, Neumann Harald. Unique transcriptome signature of mouse microglia. Glia. 2013;61:1429–1442. doi: 10.1002/glia.22524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Orre Marie, Kamphuis Willem, Osborn Lana, Melief Jeroen, Kooijman Lieneke, Huitinga Inge, Klooster Jan, Bossers Koen, Hol Elly. Acute isolation and transcriptome characterization of cortical astrocytes and microglia from young and aged mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chiu Isaac, Morimoto Emiko, Goodarzi Hani, Liao Jennifer, O’Keeffe Sean, Phatnani Hemali, Muratet Michael, Carroll Michael, Levy Shawn, Tavazoie Saeed, Myers Richard, Maniatis Tom. A neurodegeneration-specific gene-expression signature of acutely isolated microglia from an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model. Cell Rep. 2013;4:384–401. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bandyopadhyay Urmi, Cotney Justin, Nagy Maria, Oh Sunghee, Leng Jing, Mahajan Milind, Mane Shrikant, Fenton Wayne, Noonan James, Horwich Arthur. RNA-seq profiling of spinal cord motor neurons from a presymptomatic SOD1 ALS mouse. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang Ye, Chen Kenian, Sloan Steven, Bennett Mariko, Scholze Anja, O’Keeffe Sean, Phatnani Hemali, Guarnieri Paolo, Caneda Christine, Ruderisch Nadine, Deng Shuyun, Liddelow Shane, Zhang Chaolin, Daneman Richard, Maniatis Tom, Barres Ben, Wu Jai-qian. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2014;34:11929–11947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lerch Jessica, Kuo Frank, Motti Dario, Morris Richard, Bixby John, Lemmon Vance. Isoform diversity and regulation in peripheral and central neurons revealed through RNA-seq. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lai Eric, Tam Bergin, Rubin Gerald. Pervasive regulation of Drosophila Notch target genes by GY-box-, Brd-box-, and K-box-class microRNAs. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1067–1080. doi: 10.1101/gad.1291905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Doetsch Fiona, Caille Isabelle, Lim Daniel, Garcia-Verdugo Jose, Alvarez-Buylla Arturo. Subventricular zone astrocytes are neural stem cells in the adult mammalian brain. Cell. 1999;97:703–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Edman Linda, Mira Helena, Arenas Ernest. The beta-chemokines CCL2 and CCL7 are two novel differentiation factors for midbrain dopaminergic precursors and neurons. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:2123–2130. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Njie eMalick, Boelen Ellen, Stassen Frank, Steinbusch Harry, Borchelt David, Streit Wolfgang. Ex vivo cultures of microglia from young and aged rodent brain reveal age-related changes in microglial function. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:195.e1–195.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sierra Amanda, Gottfried-Blackmore Andres, McEwen Bruce, Mulloch Karen. Microglia derived from aging mice exhibit an altered inflammatory profile. Glia. 2007;55:412–424. doi: 10.1002/glia.20468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mortazavi Ali, Williams Brian, McCue Kenneth, Lorian Shaeffer L, Wold Barbara. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tang Fuchou, Barbacioru Catalin, Nordman Ellen, Xu Nanlan, Bashkirov Vladimir, Lao Kaiqin, Surani Azim. RNA-seq analysis to capture the transcriptome landscape of a single cell. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:516–535. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Belanger Mireille, Allaman Igor, Magistretti Pierre. Brain energy metabolism: focus on astrocyte-neuron metabolic cooperation. Cell Metab. 2011;14:724–738. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bouzier-Sore Anne-Karine, Pellerin Luc. Unraveling the complex metabolic nature of astrocytes. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:179. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lobon Vincent, Petersen Kitt, Cline Gary, Shen Jun, Mason Graeme, Dufour Sylvie, Behar Kevin, Shulman Gerald. Astroglial contribution to brain energy metabolism in humans revealed by 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy: elucidation of the dominant pathway for neurotransmitter glutamate repletion and measurement of astrocytic oxidative metabolism. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1523–1531. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01523.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Itoh Yoshiaki, Esaki Takanori, Shimoji Kazuaki, Cook Michelle, Law Mona, Kaufman Elaine, Sokoloff Louis. Dichloroacetate effects on glucose and lactate oxidation by neurons and astroglia in vitro and on glucose utilization by brain in vivo . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4879–4884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0831078100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Walz Wolfgang, Mukerji Srimathie. Lactate release from cultured astrocytes and neurons: a comparison. Glia. 1988;1:366–370. doi: 10.1002/glia.440010603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McCarthy Ken, de Vellis Jean. Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. J Cell Biol. 1980;85:890–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.3.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Simard Marie, Arcuino Gregory, Takano Takahiro, Liu Qing, Nedergaard Maiken. Signaling at the gliovascular interface. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9254–9262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09254.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Volterra Andrea, Meldolesi Jacopo. Astrocytes, from brain glue to communication elements: the revolution continues. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:626–640. doi: 10.1038/nrn1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wilhelm Alexander, Volknandt Walter, Langer David, Nolte Christine, Kettenmann Helmut, Zimmermann Herbert. Localization of SNARE proteins and secretory organelle proteins in astrocytes in vitro and in situ. Neurosci Res. 2004;48:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang Jack, Kunzevitzky Noelia, Dugas Jason, Cameron Meghan, Barres Ben, Goldberg Jeffrey. Disease gene candidates revealed by expression profiling of retinal ganglion cell development. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8593–8603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4488-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.LoVerso Peter, Wachter Christopher, Cui Feng. Cross-species transcriptomic comparison of in vitro and in vivo mammalian neural cells. Bioinfo Biol Insights. 2015;9:153–164. doi: 10.4137/BBI.S33124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]