Abstract

Objectives:

Comparison of Helicobacter pylori eradication rates, side effects, compliance, cost, and ulcer recurrence of sequential therapy (ST) with that of concomitant therapy (CT) in patients with perforated duodenal ulcer following simple omental patch closure.

Methods:

Sixty-eight patients with perforated duodenal ulcer treated with simple closure and found to be H. pylori positive on three months follow-up were randomized to receive either ST or CT for H. pylori eradication. Urease test and Giemsa stain were used to assess for H. pylori eradication status. Follow-up endoscopies were done after 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year to evaluate the ulcer recurrence.

Results:

H. pylori eradication rates were similar in ST and CT groups on intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis (71.43% vs 81.80%,P = 0.40). Similar eradication rates were also found in per-protocol (PP) analysis (86.20% vs 90%,P = 0.71). Ulcer recurrence rate in ST groups and CT groups at 3 months (17.14% vs 6.06%,P = 0.26), 6 months (22.86% vs 9.09%,P = 0.19), and at 1 year (25.71% vs 15.15%,P = 0.37) of follow-up was also similar by ITT analysis. Compliance and side effects to therapies were comparable between the groups. The most common side effects were diarrhoea and metallic taste in ST and CT groups, respectively. A complete course of ST costs Indian Rupees (INR) 570.00, whereas CT costs INR 1080.00.

Conclusion:

H. pylori eradication rates, side effects, compliance, cost, and ulcer recurrences were similar between the two groups. The ST was more economical compared with CT.

Key Words: Antibiotic therapy, Helicobacter pylori eradication, patient compliance, peptic ulcer perforation

The role of H. pylori in the complicated peptic ulcer disease, particularly perforated duodenal ulcer has been emphasized by various studies. Kumar and Sinha in their study on patients who underwent surgery for perforated duodenal ulcer found that active duodenal ulcer was significantly higher in patients who had H. pylori infection in the postoperative follow up endoscopy and concluded that H. pylori was the single most important factor for the persistence of ulcer after surgery.[1] Mihmanli et al. studied patients of perforated duodenal ulcer who underwent bilateral truncal vagotomy and Weinberg pyloroplasty along with excision of ulcer with the pyloric ring, and found that H. pylori was present throughout the wall of the ulcer and noticed the high ratio of H. pylori-positive antral biopsy in these patients indicating the importance of eradicating this organism in the complicated peptic ulcer disease patients.[2] The International Agency for Research on cancer, classified H. pylori as a definite carcinogen and recommends eradication of this organism in all the positive cases. Although there is no documentation to suggest that patients of perforated duodenal ulcer have more virulent organisms, the eradication of H. pylori to prevent ulcer recurrence after duodenal ulcer perforation has been shown to be effective, in other studies.[3,4,5]

The standard triple therapy (STT) treatment regimen, which includes proton pump inhibitors (PPI), clarithromycin, and amoxicillin or metronidazole, proposed at the first Maastricht conference to treat H. pylori infection has become universally accepted and is being widely used for eradication of H. pylori, especially in developing countries.[6] Vaira et al. have reported an inconsistent eradication rate of H. pylori infection with STT.[7] Recently Graham and Fischbach showed that among the studies published regarding STT, 60% of the studies failed to reach 80% treatment success, and only 18% had treatment success exceeding 85%.[8] Several other investigators from the West have reported low eradication rates for STT. With the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains, newer regimens to achieve higher eradication rate became necessary.

Sequential therapy (ST) with four drugs is defined as use of one PPI and amoxicillin for first 5 days followed by PPI plus clarithromycin and metronidazole for next 5 days.[9] Several studies have shown that ST was more effective than STT.[6,10,11] Concomitant therapy (CT) is defined as the use of one PPI, clarithromycin, metronidazole, and amoxicillin for 10 days and is found to have a higher eradication rate than STT.[12]

There are limited studies comparing the eradication rates for H. pylori between ST and CT especially in developing countries like India, where the burden of H. pylori infection is much more than that of developed countries. Although there were reports comparing ST and CT for eradication of H. pylori, no reports are available in the literature comparing the efficacy of ST with CT in the prevention of ulcer recurrence in patients with duodenal ulcer perforation following simple closure.[13] Hence, this study was undertaken to compare the efficacy, safety profile, compliance between ST and CT for the eradication of H. pylori, and the prevention of ulcer recurrence in patients with duodenal ulcer perforation following simple closure.

METHODS

This study was carried out in the Department of Surgery in a tertiary care hospital over a period of two years. The study included all consecutive patients who presented to the Institute's Emergency Medical Services with perforated duodenal ulcer and underwent emergency laparotomy with simple closure and were found to be positive for H. pylori infection. Positivity for H. pylori infection was diagnosed in these patients at their third-month visit following surgery. Patients were advised to stop the PPI at least 8 weeks before the endoscopy.

Exclusion criteria included patients who were found to have perforated gastric ulcer, who had undergone any other procedure apart from the simple closure for duodenal ulcer perforation, re-perforations, those who had associated upper gastrointestinal diseases, and those who had undergone any definitive surgery for peptic ulcer disease.

The study was designed as a prospective parallel arm randomized controlled trail. Block randomization was done using computer program with randomly selected block sizes of 4 and 6. Allocation concealment was ensured by serially numbered opaque sealed envelope (SNOSE). The sample size was calculated using OPENEPI® software. Considering the detection of eradication rate more than 15% between the two regimens on two–tail basis with 95% confidence interval and power of the study >80% and expected drop out rate of 10%, the sample size was calculated to be 35 in each group. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

All patients meeting the inclusion criteria were subjected to upper gastrointestinal endoscopy after getting informed written consent. A 2% lignocaine viscous is used as a local anesthetic allowing a contact time of 5 min. Biopsies were taken from antrum and corpus (two each from both sites) using endoscopic biopsy forceps. One biopsy specimen from antrum and corpus was used for urease test while two other were for Giemsa staining. All endoscopies were done by experienced consultant endoscopists in our department.

Diagnosis of H. pylori infection was done by urease test and histology by Giemsa stain. Urease test was done using a solution standardized in our institute.[14] Two gastric mucosal biopsies were put in the solution at room temperature for 24 h. Urease test was considered positive for H. pylori infection when the color of the solution changed from yellow to pink. The patient was considered positive for H. pylori status if either or both the tests were positive for H. pylori. The patient was considered negative for H. pylori infection if both tests were negative.

H. pylori-positive patients were randomized into two groups using the opaque sealed envelope technique. One group received ST while the other received CT. ST comprised omeprazole 20 mg twice a day and amoxicillin 1 gm twice a day for the first five days and omeprazole 20 mg twice a day, clarithromycin 500 mg twice a day and metronidazole 400 mg thrice a day for the next five days. Total duration of treatment was 10 days. CT comprised omeprazole 20 mg twice a day, clarithromycin 500 mg twice a day, amoxicillin 1 gm twice a day, and metronidazole 400 mg thrice a day for 10 days.

Compliance and side effects were assessed after finishing anti-H. pylori therapy by semi-structured interview method allowing the patients to state the reason for noncompliance and side effects in addition to those mentioned in the questionnaires. Patient compliance was assessed as to what extent patient adhered to the schedule and duration of treatment. Patients who did not follow the schedule or those who could not complete the prescribed duration of treatment were considered as noncompliant. A follow-up of these patients was done at 3, 6, and 12 months after index endoscopy. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was done to assess the eradication rate of H. pylori following ST and CT at three-month follow-up. Ulcer recurrence was noted during follow-up endoscopies.

This study was approved by the Institute's Research Council and the Ethics Committee. The nature, methodology, and risks involved in the study were explained to the patients and an informed consent was obtained. All the information collected was kept confidential and patients were given full freedom to withdraw at any point during the study. All provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed in this study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using GraphpadInstat Software version 3.0 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA, USA). Fisher's exact test was used to analyze H. pylori eradication, ulcer recurrence, side effects of ST and CT, and for the assessment of compliance of regimens. A P value < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Results were reported in intention-to-treat (ITT), modified intention-to-treat (mITT), and per-protocol (PP) analysis. In mITT lost in follow-up patients were excluded from the analysis.

RESULTS

In the present study out of 105 patients present for initial endoscopy, 68 patients were H. pylori positive (64.76%) [Figure 1]. The mean age in ST and CT group was 44.11 ± 13.75 and 42.45 ± 13.65 years, respectively. The male-to-female ratio in both the groups did not vary significantly (91/9% vs 88/12%; P = 0.7053).

Figure 1.

The overall scheme as per CONSORT flowchart. DU = Duodenal ulcer, H. pylori = Helicobacter pylori, ST = Sequential therapy; CT = Concomitant therapy; UGIE = Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy; ER = Eradication rate. *Allocation concealment was done by opaque sealed envelope method

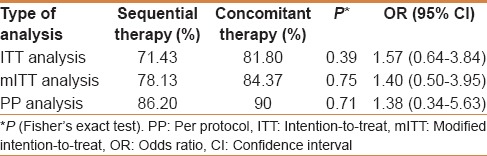

The eradication rate of H. pylori in perforated duodenal ulcer patients treated with ST and CT was 71.43% vs 81.80% (P = 0.39) by ITT. By mITT the eradication with ST and CT was 78.13% versus 84.37% (P = 0.75) and by PP analysis it was 86.20% versus 90% (P = 0.71) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparing the Helicobacter pylori eradication rates with the sequential therapy and the concomitant therapy

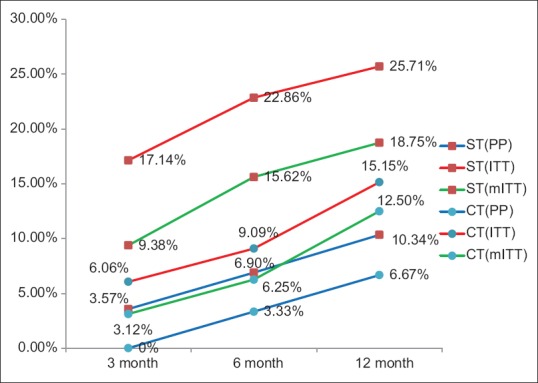

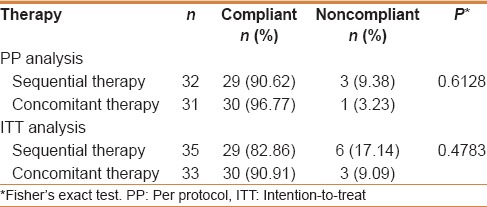

Ulcer recurrence rates in ST groups and CT groups were (17.14% vs 6.06%, P = 0.26) and (3.17% vs 0%; P = 0.49) at 3 months, (22.86% vs 9.09%, P = 0.19) and (6.90% vs 3.33%; P = 0.6) at 6 months, and (25.71% vs 15.15%; P = 0.37) and (10.34% vs 6.67%; P = 0.67) at 1 year of follow-up by ITT and PP analysis, respectively [Figure 2]. None of the H. pylori eradicated patients had ulcer recurrence. In H. pylori failure patients, ulcer recurrence in ST groups and CT groups were (90% vs 75%, P = 0.63) and (83% vs 66%, P = 0.71) at 1 year of follow up by ITT and PP analysis. Compliance in ST and CT groups was 90.62% and 96.77% (P = 0.61), respectively [Table 2]. Most common side effects in ST and CT were diarrhea (27.59%) and metallic taste (26.67%), respectively [Table 3]. The cost of a complete course of ST was 570 INR and 1080 INR for CT.

Figure 2.

Comparison of ulcer recurrence following sequential therapy and concomitant therapy at 3, 6, and 12 months by PP = Per-protocol, ITT = Intention-to-treat, mITT = Modified intention-to-treat analysis, CT = Concomitant therapy, ST = Sequential therapy

Table 2.

Comparison of the compliance between the sequential therapy and the concomitant therapy per protocol and intention-to-treat analysis

Table 3.

Comparison of side effects in the sequential therapy with those in the concomitant therapy group

DISCUSSION

H. pylori prevalence in perforated duodenal ulcer varies in different parts of the world. Earlier reports from this institute showed a prevalence of H. pylori infection in perforated duodenal ulcer ranging from 56% to 65%.[5,15,16] H. pylori prevalance in the present study was 64.76%. In the present study, ST achieved an eradication of 71.43%, 78.13%, and 86.20% by ITT, mITT, and PP analyses, respectively. An earlier study done in our institute showed an eradication rate of 73% and 87% by ITT and PP analysis, respectively, with ST where amoxicillin was used in the second phase.[16] In the present study, instead of amoxicillin, we used metronidazole during the second 5 days of ST. Another study in India showed ITT and PP eradication rates of 76% and 84.6%, respectively, with ST.[17] In a study done by Vaira et al., ST achieved an eradication rate of 89%, 91%, and 93% by ITT, mITT, and PP analysis, respectively.[7] A meta-analysis by Gatta et al. of 46 studies showed an overall eradication rate of 84.3% by ST.[9]

Wu et al., Molina-Infante et al., and Kongchayanun et al. evaluated 10-day CT against H. pylori, which showed ITT eradication rates of 93%, 87%, and 96%, and PP eradication rates of 93%, 89%, and 96%, respectively.[13,18,19] Georgopoulos et al. Showed that CT achieved ITT and PP eradication rates of 91.6% and 94.5%, respectively.[12] In the present study, CT group achieved ITT, mITT, and PP eradication rates of 81.80%, 84.37%, and 90%, respectively. A meta-analysis of 19 studies involving 2070 patients by Gisbert and Calvet revealed H. pylori eradication rate of 88% by ITT analysis.[20]

McNicholl et al. compared the eradication rates of CT and ST and found that CT has a better eradication rate (91% vs 86% by ITT and 87% vs 81% by PP analysis), but not statistically significant.[21] Wu et al. in their study found equal effectiveness for both the therapies.[13] Lim et al. concluded that two-week ST and CT were of suboptimal efficacy.[22] In a study done in Palestine, Abu-Safieh failed to show an acceptable eradication by both ST and CT.[23] A meta-analysis of six studies comparing ST with CT (1039 vs 1031 patients) showed an eradication rate of 81.7% and 81.3%, respectively.[9] In the present study, CT achieved better eradication rates compared with ST, but this did not achieve statistical significance. Primary clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance rates in India are 33% and 78%, respectively, which are higher than in other countries. Metronidazole has been used as a part of standard ST and CT regimen in majority of the studies. Although metronidazole resistance is more prevalent compared with the other drugs used for H. pylori eradication, it has not changed over the years. It is also emphasized that metronidazole resistance has less impact in H. pylori eradication therapy than that of the clarithromycin resistance and this resistance can be overcome by increasing the dose and the duration of the treatment.[24,25] This high rate of antimicrobial resistance is probably because of injudicious use of antibiotics for various diseases.

Ulcer recurrence rates are highly variable in different studies in different parts of the world.[26,27] In an earlier study conducted in our institute, Bose et al. found out that eradication of H. pylori infection in patients with perforated duodenal ulcer, treated with simple closure, decreases the rate of ulcer recurrence significantly.[5] In the present study, the differences in ulcer recurrence rates between the two groups at 3, 6, and 12 months by ITT, mITT, and PP analysis were not statistically significant. High recurrence rates in both the ST and CT might be due to noncompliance to treatment or might be due to re-infection of H. pylori as a result of poor socioeconomic conditions. A study with more number of study subjects is needed to get a broader picture of ulcer recurrence following ST and CT.

Compliance in ST and CT groups were 90.62% and 96.77%, respectively. CT group has better compliance, but the difference was not statistically significant. In a study by Wu et al. compliance in ST and CT were 95.7% and 98.2%.[13] Lim et al. in their study showed a better compliance with CT than ST (95.3% vs. 96.2%; P value = 0.80).[22] Lesser compliance for both CT and ST (82.7% vs 82.4%; P value = 0.93) was shown in a study by McNicholl et al.[21] Even though ST is having lesser number of tablets, its complex dosage schedule makes its use difficult for the patient. The success in eradication of H. pylori using ST was postulated to be because of its sequential nature of dosage schedule and due to increase in the number of antibiotics. Hence, if compliance is not maintained in ST, the effectiveness of the therapy will decrease. Higher compliance for CT seen in this study might be due to less complex dosage schedule.

Most common side effects in ST and CT were diarrhea (27.59%) and metallic taste (26.67%), respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in side effects profile between the two groups. Wu et al. in their study found bad taste (15.7%) as a major side effect in the concomitant group and fatigue in sequential group (11%).[13] Diarrhea was the major side effect in both ST and CT groups in a study done by De Francesco et al.[28] Kongchayanun et al. in their study found bitter taste, epigastric soreness, and diarrhea as the most common side effects in both groups.[19]

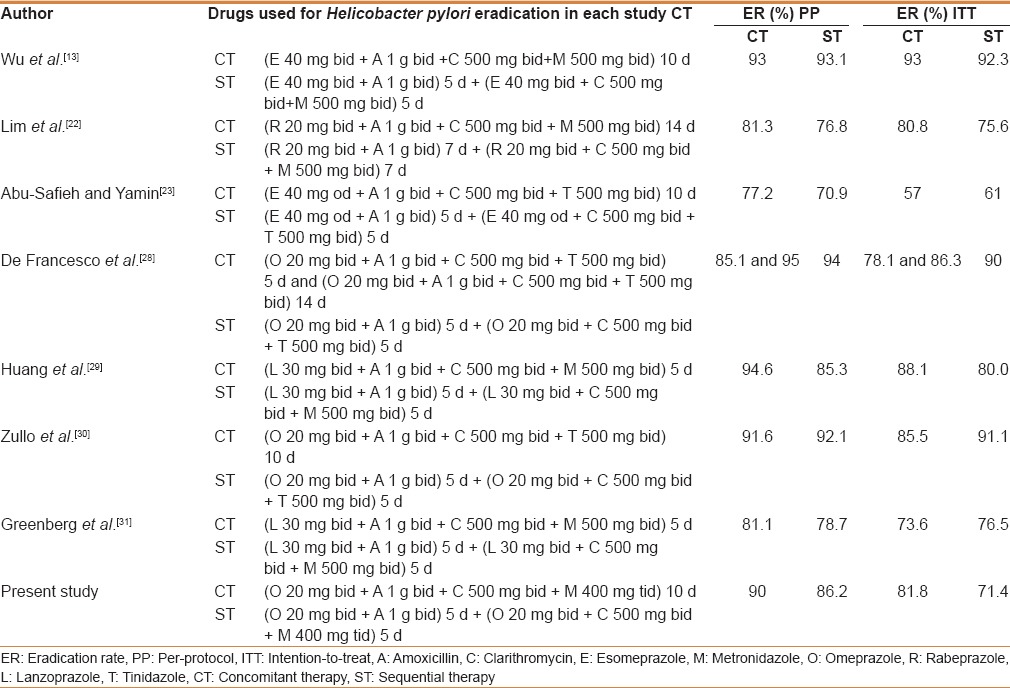

The cost of a complete course of ST was 570 INR and 1080 INR for CT. ST was economically better than CT. H. pylori eradication with CT and ST shows a wide variation in different parts of the world. This difference might be due to the difference in regional antibiotic resistance patterns against H. pylori. Based on Graham et al.'s proposed report card to grade H. pylori eradication regimen, except study by De Francesco et al. for CT, none of the studies got grade A result, which is deemed acceptable for prescription in clinical practice [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of Helicobacter pylori eradication rate between concomitant therapy and sequential therapy in various studies by per protocol and intention-to-treat analysis

CONCLUSION

In the present study, it was found that the H. pylori eradication rates with ST and CT were similar. The ulcer recurrence rates in both the groups were comparable. Both the regimens have comparable compliance and side effects profile. Hence ST can be considered as a better economical option than CT in the treatment of H. pylori infection.

As the prevalence of H. pylori is high in developing countries such as India, and various studies showing unacceptable eradication rates, therapy based on antibiotic sensitivity pattern needs to be prescribed for H. pylori eradication. Research on developing newer molecules for the eradication of H. pylori is required as clarithromycin-based regimen is losing its charm as a potential killer of H. pylori.

Study highlights

Standard triple therapy is no longer preferred as the first treatment of choice for H. pylori eradication

Newer H. pylori eradication regimen such as sequential therapy and concomitant therapy are in the horizon for the past few years with inconsistent results

In the present study, it was found that sequential therapy and concomitant therapy have similar eradication rates and ulcer recurrence rates

Sequential therapy is an economically better option than concomitant therapy especially in developing countries such as India.

Limitation of the study

Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance pattern could not be anayzed for H. pylori in the present study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.[31]

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumar D, Sinha AN. Helicobacter pylori infection delays ulcer healing in patients operated on for perforated duodenal ulcer. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2002;21:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mihmanli M, Isgor A, Kabukcuoglu F, Turkay B, Cikla B, Baykan A. The effect of H. pylori in perforation of duodenal ulcer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1610–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N, Badrinath S. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the ulcer recurrence rate after simple closure of perforated duodenal ulcer: Retrospective and prospective randomized controlled studies. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1054–8. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gisbert JP, Pajares JM. Helicobacter pylori infection and perforated peptic ulcer prevalence of the infection and role of antimicrobial treatment. Helicobacter. 2003;8:159–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bose AC, Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N, Parija SC. Helicobacter pylori eradication prevents recurrence after simple closure of perforated duodenal ulcer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:345–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection – The Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–64. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaira D, Zullo A, Vakil N, Gatta L, Ricci C, Perna F, et al. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:556–63. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2010;59:1143–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.192757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gatta L, Vakil N, Vaira D, Scarpignato C. Global eradication rates for Helicobacter pylori infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis of sequential therapy. BMJ. 2013;347:f4587. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zullo A, Vaira D, Vakil N, Hassan C, Gatta L, Ricci C, et al. High eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori with a new sequential treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:719–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatta L, Vakil N, Leandro G, Di Mario F, Vaira D. Sequential therapy or triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults and children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3069–79. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Georgopoulos S, Papastergiou V, Xirouchakis E, Laoudi F, Lisgos P, Spiliadi C, et al. Nonbismuth quadruple “concomitant” therapy versus standard triple therapy, both of the duration of 10 days, for first-line H. pylori eradication: A randomized trial. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:228–32. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31826015b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu DC, Hsu PI, Wu JY, Opekun AR, Kuo CH, Wu IC, et al. Sequential and concomitant therapy with four drugs is equally effective for eradication of H. pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:36–41.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prasad S, Mathan M, Chandy G, Rajan DP, Venkateswaran S, Ramakrishna BS, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Southern Indian controls and patients with gastroduodenal disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;9:501–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1994.tb01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gopal R, Elamurugan TP, Kate V, Jagdish S, Basu D. Standard triple versus levofloxacin based regimen for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2013;4:23–7. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v4.i2.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valooran GJ, Kate V, Jagdish S, Basu D. Sequential therapy versus standard triple drug therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with perforated duodenal ulcer following simple closure. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1045–50. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.584894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Javid G, Zargar SA, Bhat K, Khan BA, Yatoo GN, Gulzar GM, et al. Efficacy and safety of sequential therapy versus standard triple therapy in Helicobacter pylori eradication in Kashmir India: A randomized comparative trial. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013;32:190–4. doi: 10.1007/s12664-013-0304-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molina-Infante J, Pazos-Pacheco C, Vinagre-Rodriguez G, Perez-Gallardo B, Dueñas-Sadornil C, Hernandez-Alonso M, et al. Nonbismuth quadruple (concomitant) therapy: Empirical and tailored efficacy versus standard triple therapy for clarithromycin-susceptible Helicobacter pylori and versus sequential therapy for clarithromycin-resistant strains. Helicobacter. 2012;17:269–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kongchayanun C, Vilaichone RK, Pornthisarn B, Amornsawadwattana S, Mahachai V. Pilot studies to identify the optimum duration of concomitant Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in Thailand. Helicobacter. 2012;17:282–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gisbert JP, Calvet X. Update on non-bismuth quadruple (concomitant) therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2012;5:23–34. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S25419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNicholl AG, Marin AC, Molina-Infante J, Castro M, Barrio J, Ducons J, et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing sequential and concomitant therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication in routine clinical practice. Gut. 2014;63:244–9. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim JH, Lee DH, Choi C, Lee ST, Kim N, Jeong SH, et al. Clinical outcomes of two-week sequential and concomitant therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A randomized pilot study. Helicobacter. 2013;18:180–6. doi: 10.1111/hel.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abu-Safieh Y, Yamin H. Sequential and concomitant non-bismuth quadruple therapies are ineffective for H. pylori eradication in Palestine. A randomized trial. Open J Gastroenterol. 2012;2:177–80. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thung I, Aramin H, Vavinskaya V, Gupta S, Park JY, Crowe SE, et al. Review article: The global emergence of Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:514–33. doi: 10.1111/apt.13497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith SM. An update on the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. EMJ Gastroenterol. 2015;4:101–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coghlan JG, Gilligan D, Humphries H, McKenna D, Dooley C, Sweeney E, et al. Campylobacter pylori and recurrence of duodenal ulcers – A 12-month follow-up study. Lancet. 1987;2:1109–11. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91545-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nanivadekar SA, Sawant PD, Patel HD, Shroff CP, Popat UR, Bhatt PP. Association of peptic ulcer with Helicobacter pylori and the recurrence rate. A three year follow-up study. J Assoc Physicians India. 1990;38(Suppl 1):703–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Francesco V, Hassan C, Ridola L, Giorgio F, Ierardi E, Zullo A. Sequential, concomitant and hybrid first-line therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A prospective randomized study. J Med Microbiol. 2014;63(Pt 5):748–52. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.072322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang YK, Wu MC, Wang SS, Kuo CH, Lee YC, Chang LL, et al. Lansoprazole-based sequential and concomitant therapy for the first-line Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:232–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2012.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zullo A, Scaccianoce G, De Francesco V, Ruggiero V, D'Ambrosio P, Castorani L, et al. Concomitant, sequential, and hybrid therapy for H. pylori eradication: A pilot study. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:647–50. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenberg ER, Anderson GL, Morgan DR, Torres J, Chey WD, Bravo LE, et al. 14-day triple, 5-day concomitant, and 10-day sequential therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection in seven Latin American sites: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;378:507–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60825-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]