Abstract

Inositol phospholipids play an important role in the transfer of signaling information across the cell membrane in eukaryotes. These signals are often governed by the phosphorylation patterns on the inositols, which are mediated by a number of inositol kinases and phosphatases. The src homology 2 (SH2) – containing inositol 5-phosphatase (SHIP) plays a central role in these processes, influencing signals delivered through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. SHIP modulation by small molecules has been implicated as a treatment in a number of human disease states, including cancer, inflammatory diseases, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and Alzheimer's disease. In addition, alteration of SHIP phosphatase activity may provide a means to facilitate bone marrow transplantation and increase blood cell production. This review discusses the cellular signaling pathways and protein-protein interactions that provide the molecular basis for targeting the SHIP enzyme in these disease states. In addition, a comprehensive survey of small molecule modulators of SHIP1 and SHIP2 is provided, with a focus on the structure, potency, selectivity and solubility properties of these compounds.

Keywords: SHIP, inositol phosphatase, PI3K, drug development, enzyme inhibition, enzyme agonist

Phosphatidylinositols play important roles in cellular signaling. The phosphorylation pattern on these lipids acts as a recognition element for protein kinases involved in signal transduction pathways, and therefore inositol phosphorylation is tightly regulated by inositol kinases and phosphatases. Modulation of inositol kinases and phosphatases has become a hotly pursued area of medicinal research, as aberrant regulation of these enzymes is implicated in a number of human disease states. In this review we provide an overview examining the role src homology 2 (SH2) – containing inositol 5-phosphatase (SHIP) plays in cellular signaling, evaluate the potential of SHIP modulation for the treatment of several ailments, and for the first time comprehensively examine progress in the development of small molecule SHIP modulators. For more in depth coverage of specific topics, the reader is directed to reviews on the enzymology of inositol 5-phosphatases,1-4 the PI3K pathway5,6 or other reviews of the role of SHIP specific isoforms in disease.7-12

I. Role of SHIP in Cellular Signaling

In order to react to changes in their surroundings, eukaryotic cells must be able to transfer information about the extracellular environment through the plasma membrane to the nucleus. Passage of these signals is often mediated by membrane receptors that are activated by a variety of extracellular stimuli. These receptors then initiate a signaling cascade through a complex network of enzymes and second messengers inside the cell, resulting in a number of intracellular events. Phosphatidyl inositols have become recognized as key participants in many of these signaling pathways. Phosphoinositides are minor phospholipid components of the cell membrane in eukaryotic cells. The pattern of phosphorylation present on the inositol ring acts as a recognition element for protein kinases, which initiate phosphorylation cascades that contribute to signaling between the cell membrane and the nucleus. Phosphoinositides play important roles in an array of cellular functions including mitogenesis, vesicle trafficking, secretion, motility, adherence, proliferation, differentiation, and cell death.13,14 A plethora of enzymes including PI3K, PTEN, SHIP and INPP4 are known to metabolize phosphatidyl inositols, which demonstrates their significance in cellular physiology and the need for their tight regulation.

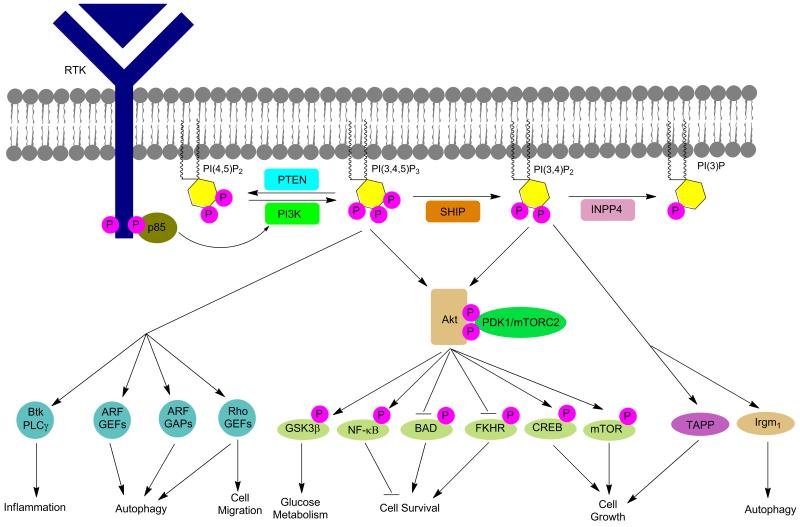

Perhaps the best known enzyme that modifies phosphatidyl inositols is phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K). PI3K is central to a major cell signaling pathway that has been shown to have widespread influence on cellular physiology.15 The PI3K pathway cannot perform its diverse effects on cellular function without its key secondary messenger, phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PI(3,4,5)P3, Figure 1), which is normally maintained at a low concentration. However, upon activation by extracellular stimuli, PI3K can quickly synthesize PI(3,4,5)P3 from phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2), rapidly increasing the intracellular concentration of this phosphoinositide.16 PI(3,4,5)P3 located on the intracellular leaflet of the plasma membrane directly binds and thereby recruits signaling proteins with pleckstrin homology (PH) domains to the membrane. Some of these proteins are serine-threonine kinases, such as protein kinase B (Akt) and phosphoinositide kinase 1 (PDK1); protein tyrosine kinases, such as the Tec family; exchange factors for guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-binding proteins, such as the general receptor for phosphoinositide 1 (Grp1) and the Rac family (subfamily of Rho GTP-binding proteins); and adaptor proteins (Figure 2).15 Upon activation these proteins initiate still more signaling cascades, ultimately influencing molecular trafficking, vesicle mediated transport, regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, GTPase function, development, movement, organization, growth, and proliferation.14 In addition, the Prestwich laboratory has also shown that PI(3,4,5)P3 influences neutrophil migration and insulin signaling.17 Due to the pervasive influence of PI(3,4,5)P3 and its associated proteins, the hyper- or hypo-activation of the PI3K pathway has been implicated in many altered human metabolic states such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer's disease, allergies and autoimmune disorders.14 As a result, many enzymatic components of this pathway have become major pharmacological targets for therapeutic intervention.15

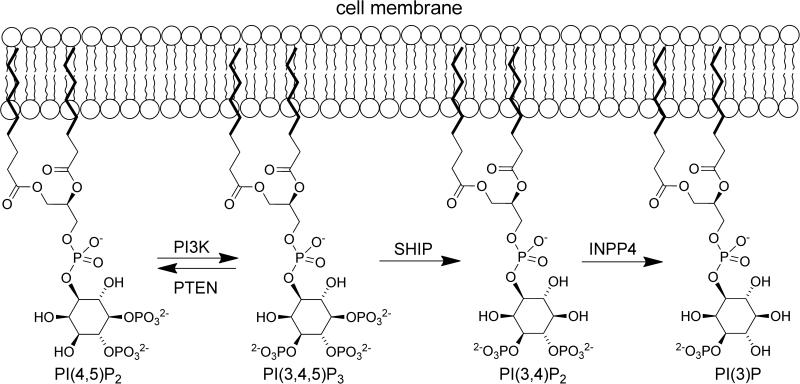

Figure 1.

Modification of inositols mediated by PI3K, PTEN, SHIP and INPP4.

Figure 2.

Inositols and cellular signaling pathways.

The formation of PI(3,4,5)P3 is governed by the kinase, PI3K, which forms the phosphoinositide once it is activated by a nearby receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK). Inositol phosphatases influence PI(3,4,5)P3 levels by controlling the position and rate of phosphate hydrolysis. The most studied inositol phosphatases involved in processing PI(3,4,5)P3 are PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog protein) and SHIP (src homology 2 (SH2) – containing inositol 5-phosphatase).18,19 Although PTEN and SHIP can both negatively regulate the PI3K pathway, they do so in different ways. PTEN converts PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(4,5)P2 while SHIP converts PI(3,4,5)P3 to phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate (PI(3,4)P2) (Figure 1).18 By decreasing the cellular concentration of PI(3,4,5)P3, PTEN and SHIP provide an alternative inhibitory control on many of the PI3K pathway's downstream effector cascades. However, SHIP may have dual roles in PI3K signaling, as its product (PI(3,4)P3) can also lead to activation of downstream effectors of PI3K such as Akt and Irgm1.20

PTEN is primarily known as a tumor suppressor enzyme, as PTEN mutations or deletions are found in a high percentage of both hereditary and non-hereditary human cancers.18,19,21 Indeed, PTEN heterozygous mutations have been associated with Cowden disease,18 endometrial cancer, malignant melanomas,19 glioblastomas, prostate cancer, breast cancer, and T-cell and B-cell lymphomas.21 PTEN functions as an inositol lipid phosphatase; however, it also functions as a specific protein phosphatase. Despite this dual functionality, its role as an inositol lipid phosphatase is critical for its tumor suppressing activity. By hydrolyzing PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(4,5)P2, PTEN acts as a gatekeeper, keeping Akt from becoming hyperactivated.22 Overactivation of Akt prevents cells from responding to their normal apoptotic stimuli. As a result, PTEN-deficient cells survive much longer than normal, leading to abnormal tissue growth.21

While PTEN converts PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(4,5)P2, SHIP converts PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(3,4)P2. In order to catalyze this hydrolysis reaction, SHIP must be translocated from the cytoplasm, where it typically resides, to the cell membrane where PI(3,4,5)P3 is found. SHIP is recruited to the membrane through association with a wide range of major receptor complexes employing either adaptor and scaffold proteins and/or direct binding of the SHIP SH2 domain. Association of SHIP with a receptor complex allows the enzyme to hydrolyze PI(3,4,5)P3 in a localized area of the cell membrane. Hydrolysis of PI(3,4,5)P3 blocks PI3K effector pathways and thereby inhibits the further recruitment of many proteins, including important kinases such as Akt, Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk), and phospholipase C-γ (PLC-γ).23 Alternatively, as mentioned above, in certain contexts SHIP's production of PI(3,4)P2 can promote further activation of Akt due to the increased affinity of the Akt PH domain for PI(3,4)P2.24,25 This Akt activating role for SHIP appears to be especially important in malignant cells.26,27 As a result, SHIP can both negatively and positively influence various aspects of cellular pathology (Figure 2).

Two major isoforms of SHIP are associated with the PI3K pathway: SHIP1 and SHIP2. These enzymes share a high level of amino acid conservation, with both containing SH2-domains.28,29 Despite the homology in amino acid sequence, SHIP1 and SHIP2 differ considerably in their tissue distribution. Expression of SHIP1 is primarily confined to cells of the hematopoietic lineage,30 but this phosphatase is also expressed by osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells.12,30 SHIP2 is more ubiquitously expressed across all cell and tissue types. In humans, especially high levels of SHIP2 are found in the heart, skeletal muscle, and the placenta.31 Furthermore, the binding kinetics of the enzymes’ SH2 domains vary significantly.32 Differences in tissue distribution, specificity of recruitment and kinetic differences between the two enzymes are likely responsible for the dissimilar roles observed in vivo between SHIP1 and SHIP2.

These differences in the two SHIP paralogs may explain the varying roles SHIP1 and SHIP2 play in cell signaling. For example, SHIP1 functions as a negative controller in immunoreceptor signaling21 and hematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation/survival,28 and as an inducer of cellular apoptosis.29 Interestingly, SHIP1 has also been implicated both as a hematopoietic tumor suppressor and activator.11 Although SHIP1 has only been found to have a tumor suppressive role in a single murine B cell lymphoma model driven by c-Myc oncogene model in mice,33 no studies to date demonstrate that SHIP1 is a tumor suppressor in spontaneous malignancies occurring in the human population. SHIP1 knockout mice demonstrate the physiological significance of SHIP1 for immune homeostasis. While these mice are viable and fertile, they display several abnormal pathologies, such as progressive splenomegaly28 (enlargement of the spleen), massive infiltration and consolidation of the lungs by macrophages29 and a shortened life span. By the time these mice are 14 weeks old, their chance of survival is only 40%.34 This combined data confirms the importance of SHIP1 in the proper functioning of certain cells and thus its importance for normal physiology.

In contrast, SHIP2 has been reported to act as an important negative regulator of the insulin-signaling pathway.35 SHIP2 knockout mice are viable and showed reduced body weight despite increased food intake.36 In addition, when placed on a high-fat diet the SHIP2 knockout mice were almost completely resistant to weight gain over a 12-week period. Over this time period the mice exhibited no increase in serum lipids and did not develop hyperglycemia or hyperinsulinamia. These results are attributed to enhanced insulin-stimulated Akt and p70S6K activation in the liver.

Adding to the complexity of SHIP in cell signaling, several groups have demonstrated a role played by microRNAs in SHIP1 regulation. These small non-coding RNA molecules function by repressing specific target genes through direct 3’-UTR interactions. Specifically, microRNA-155 (miR-155) has been implicated as influencing the expression of SHIP1.37-39 Both miR-155 and SHIP1 regulate critical and overlapping functions in a number of different cells, particularly in the immune system, with a molecular link between miR-155 and SHIP1 providing evidence that repression of SHIP1 is an important constituent of miR-155 biology.

Further complicating the biological role of SHIP is the propensity of the proteins to not only act as phosphatases, but also as docking partners for a number of other soluble proteins.40,41 These docking partners include proteins with roles in cytoskeletal dynamics, and therefore these interactions may effect changes in endocytosis, cell migration and cell adhesion that are not involved with the phosphatase activity of SHIP. Additionally SHIP may block the recruitment of key signaling molecules to protein complexes, leading to negative regulation of certain signaling pathways.11,42,43 Differentiating between the phosphatase activity and the scaffolding activity of SHIP is difficult with genetic methods, but small molecule inhibitors of the phosphatase activity may provide a means to distinguish between these two roles.

II. Potential of SHIP Modulation in the Treatment of Disease

Adjustment of intracellular PI(3,4,5)P3 concentrations has become a hotly pursued goal in the pharmaceutical industry as this molecule plays a critical role in signal transduction. Controlling the synthesis of PI(3,4,5)P3 by inhibiting PI3K has been the most heavily pursued strategy,5,44,45 and while several excellent inhibitors have been developed, efforts have been complicated by the requirement of selectively targeting numerous PI3K isoforms to efficiently disrupt PI3K signaling.46,47 An alternative approach to lowering PI(3,4,5)P3 levels in cells is to upregulate the phosphatase enzymes that degrade PI(3,4,5)P3, specifically PTEN or SHIP. In addition, in some disease settings, decreasing PI(3,4)P2 production by SHIP1/2 may also be merited.11 In many of these cases, genetic studies have indicated that modulation of inositol phosphatase activity may play a role in the development and progression of the disease. A number of ailments may be related to the abnormal regulation or function of inositol phosphatases, with some of them being detailed below.

1. Cancer

Aberrant activation of PI3K or loss of PTEN function has been implicated in the development of numerous types of cancer. Both of these cellular events lead to an excess of PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2, the primary PI3K products.48 Excesses of these inositol phospholipids leads to recruitment of Akt to the cell membrane, where it is subsequently activated by kinases such as PDK1.24,25,27 Akt then activates mTOR by phosphorylating TSC2, lifting the inhibitory effect of the TSC1/TSC2 complex on Reb and mTOR.49 The PI3K survival signal stems in part from Akt-mediated phosphorylation and inactivation of pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bim and Bad.50-53 Furthermore, Akt may activate transcription factors like AP-1 and NFκB, which results in the transcription of anti-apoptotic genes.54,55 Many types of cancer including breast cancer56,57 and multiple myeloma58 often exhibit aberrant activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. This overactivation is often ascribed to mutations in the PI3K gene (PIK3CA), but increased levels of PI3K signaling may also occur due to other changes in neoplastic cells.59-61 Decreasing signaling related to the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway with small molecule kinase inhibitors specific to PI3K is a highly investigated area of cancer research,3,62 and is believed to be an effective mechanism for cancer treatment regardless of the activating mechanism of the enzyme. As SHIP and PTEN can influence the amount of PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 present, their modulation with agonists and inhibitors should also have an effect on aberrant cell growth if the PI3K pathway is dysregulated.

In addition, mTOR activation has been shown extensively to inhibit the cellular process of autophagy.63 Autophagy is a mechanism where cellular components are degraded after being surrounded by double membrane autophagosomes.64 As inositol phosphatases influence mTOR activation by modulating the amount of PI(3,4,5)P3 at the cell membrane, they can exert an influence on the initiation of autophagy as well. mTOR phosphorylates autophagy–related (ATG) proteins, leading to their inactivation, restraining the autophagic process and limiting phagophore formation. Upon cellular stresses such as nutrient deficiency, mTOR is deactivated and autophagy is initiated. Although this may temporarily protect cells from cytotoxic stimuli, progression to apoptosis under prolonged cellular stress may also occur. The role of autophagy in tumorigenesis remains elusive.63,65,66 Autophagy may serve to protect cells from apoptosis-inducing agents as some evidence indicates that autophagy can be used by cancer cells to escape therapy and hence contributes to drug resistance.67,68 Alternatively, autophagy leads to a block in proliferation and can result in cell death. Indeed, induction of autophagic cell death is a key strategy of several therapeutic agents being investigated for the treatment of breast cancer, including the mTOR inhibitors curcumin, everolimus, niclosamide, and temsirolimus.63

SHIP1, SHIP2 and PTEN are typically viewed as opposing the activity of the PI3K signaling axis and therefore promoting the survival of cancer cells and tumors.9,69,70 Following this view, agonists of SHIP1 have been developed, and these molecules show significant antitumor activity that has been linked to their SHIP1 activation.71 However, there is emerging evidence that SHIP1 and SHIP2 may actually facilitate, rather than suppress, tumor cell survival in contrast to PTEN.26,27,72-75 The enzymatic activities of SHIP1 and SHIP2 are distinct from PTEN, as PTEN hydrolyses the 3’ phosphate from PI(3,4,5)P3, reversing the PI3K reaction to generate PI(4,5)P2, while SHIP1/2 selectively hydrolyze the 5’ phosphate from PI(3,4,5)P3, generating PI(3,4)P2. Accordingly, PTEN is structurally distinct, sharing less than 20% identity with SHIP, and PTEN does not possess an SH2 domain. Also noteworthy is the product of the SHIP hydrolysis, PI(3,4)P2 has a greater affinity for the PH domain of Akt than PI(3,4,5)P3, and thus, PI(3,4)P2 more potently stimulates Akt activity.24 Excess PI(3,4)P2 also provides additional docking sites at the cell membrane for recruitment and activation of PH-domain containing kinases such as Akt,11 and therefore this inositol phospholipid could be responsible for amplifying signals that are essential for the growth and survival of cancer cells. In fact, while PI(3,4,5)P3 allows the initial membrane recruitment and interaction of PH-domain containing proteins Akt and PDK-1, resulting in the phosphorylation of the former protein at catalytic activation residue T308,76 Akt requires a secondary phosphorylation event by TORC2 or DNA-PK at S473 for full activity. PTEN and SHIP also show significant differences in in vivo settings, as PTEN deletion in adult mice invariably leads to leukemia,77 while no malignancy of any type has been reported in either SHIP1 or SHIP2 germline mutant mice.34-36,78-80 These distinctions demonstrate that SHIP and PTEN exhibit distinctly different effects on Akt signaling.

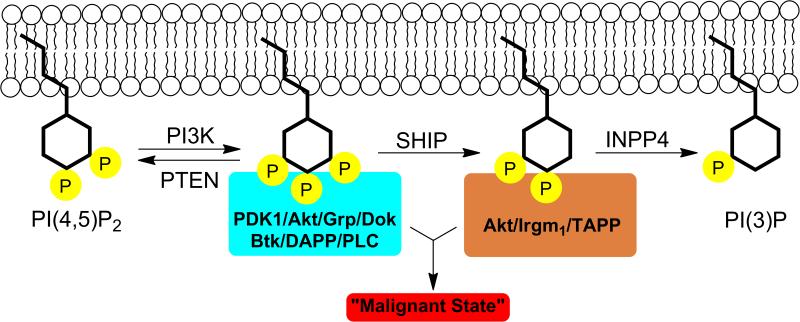

Rather than accepting SHIP as an inhibitor of the PI3K pathway, these studies suggest that SHIP may actually be a “redirector” of signaling from PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(3,4)P2, thereby recruiting a completely different set of proteins to the plasma membrane using the enzymes’ PH domain.11,26,27 This new view on SHIP1 has a number of interesting implications. For cellular functions in which SHIP1 has a negative effect, PI(3,4,5)P3 must be the main phospholipid secondary messenger that initiates the requisite pathways for the manifestation of that particular function. Conversely, for cellular functions in which SHIP1 has a positive effect, PI(3,4)P2 must be the major secondary messenger responsible for initiating the necessary pathways to effect that specific function.11 This unique take on SHIP1's cellular role led to the development of the “Two PIP Hypothesis”.11 Specifically, a certain amount of both PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 is required to initiate and sustain the malignant state (Figure 3). The proper maintenance of this delicate balance is required for the prevention of cancer. PI(3,4,5)P3's contributing role in multiple cancer cell lines has already been well established – mainly through augmented activity of Akt and other PI3K downstream effector proteins. Consistent with this postulate, both antagonistic26,27 and agonistic71 SHIP modulators have been reported to kill multiple myeloma cells. These results highlight the delicate balance of both PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 that must be maintained by cancerous cells. Multiple mutations and/or alterations in expression of PI3K, PTEN, SHIP and/or INPP4 may lead to increased levels of both PIP species, resulting in a malignant state. Thus, different perturbations in the PI3K-PTEN-SHIP1/2-INPP4 signaling cassette are possible in order for the cancer cell to satisfy the “Two PIP Hypothesis”.11

Figure 3.

Cancer and the “Two PIP Hypothesis”. Aberrant levels of both PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 contribute to abnormal signaling, sustaining the malignant state in cancer cells..

Additionally, high levels of the inositol phospholipid PI(3,4)P2 may be more effective at increasing PI3K signaling than PI(3,4,5)P3. This is perhaps due to the PH domain of Akt having a greater binding affinity for SHIP's enzymatic product, PI(3,4)P2, than its substrate, PI(3,4,5)P3.24 Thus, increased levels of PI(3,4)P2 may actually lead to stronger Akt activation than PI(3,4,5)P3, the immediate product of PI3K. SHIP may therefore mediate cancer cell growth by increasing the PI(3,4)P2 level, activating Akt, as abnormally elevated Akt activity has been well established in various cancer types. Increased levels of PI(3,4)P2 have been observed in leukemia cells,48 which is consistent with this hypothesis. Increased levels of PI(3,4)P2 due to mutations in INPP4A/B genes also promoted the transformation and tumorigenicity of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) and breast tumor formation.81-84 Studies by Brooks et al. and Fuhler et al. established that PI(3,4)P2 directly promotes increased Akt activation and survival of cancer cells, as exogenous PI(3,4)P2 introduction increases both in the presence of SHIP1/2 inhibitors.26,27 While both Akt and mTOR can be targeted directly with small molecule inhibitors, SHIP1 modulation provides a new molecular mechanism to influence this pathway. This differentiation could be advantageous for treating tumors that are resistant to Akt and/or mTOR inhibitors, as they may still be susceptible to modifying the activity of SHIP.

Alternatively, SHIP2 inhibition has been implicated as a therapeutic target for breast cancer.72-75 SHIP2 has an atypical effect on EGF-induced signaling in various breast cancer cell lines. Instead of repressing cellular responses to EGF, SHIP2 causes an increase in EGF-induced signaling by elevating the level of the EGF receptor (EGFR). Multiple breast cancer cell lines, including MDA-MB-231, SKBR-3, MDA-468, MDA-436, MCF-7, and ZR-75 all overexpress SHIP2 and display enhanced levels of EGFR. Due to their increase in EGF-induced signaling, these breast cancer cell lines exhibit an increased rate of cellular proliferation. Silencing of SHIP2 in the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line leads to dramatically decreased cell proliferation. Furthermore, SHIP2 silencing in the MDA-MB-231 line also produced a 60% increase in apoptosis in response to EGFR inhibitors.73 These results imply that SHIP2 may play a significant role in oncogenesis, especially in breast cancer. To further explore the effect of SHIP2 on tumorigenesis, orthotopic implantation was conducted on nude mice. Tumors that originated from SHIP2 deficient cells displayed delayed growth by almost three weeks as compared to tumors that came from SHIP2 sufficient cells. In addition, mice with tumors from SHIP2-silenced cells exhibited profoundly decreased spontaneous lung metastases. These mice showed either no detectable masses or just micromasses in their lungs while mice with tumors from control cells displayed extensive lung metastases that covered more than 25% of their lungs.73 These findings confirm the positive role SHIP2 has upon breast cancer growth and metastasis. Interestingly, SHIP2 silencing in HeLa cells lead to enhanced EGF receptor degradation as well as cytoskeletal anomalies, which may imply that the role SHIP2 plays in breast cancer is at least in part related to the proteins scaffolding role.40,72 These results also demonstrate that SHIP2 plays an especially significant role in breast cancer development and proliferation given that it is highly expressed in multiple breast cancer cell lines. As a result, SHIP2 is emerging as an important clinical anticancer target.

2. Inflammatory Disease

SHIP1 has been confirmed as a negative regulator of inflammatory signaling events in the immune system.11 Given SHIP1's prominent role in PI3K signaling, it is perhaps unsurprising that the enzyme plays a role in controlling cytokine secretion in the immune response. Downregulation of SHIP1 enhanced Akt signaling in several types of immunoregulatory cells including natural killer cells78 and myeloid cells, with the latter contributing to inflammation in SHIP1 knockout mice.80 Transfection and over-expression of SHIP1 in cell lines lacking the enzyme causes a marked decrease in Akt phosphorylation.85-87 Additionally, SHIP1 knockout mice have been shown to display systemic mast cell hyperplasia, increased serum levels of IL-6, TNF, and IL-5, and heightened anaphylactic response.88 For example, pulmonary inflammation induced by introduction of peptidoglycan is much more severe in SHIP1 knockout mice than in control mice with normal levels of SHIP1.89 Given these results, increasing the activity of SHIP1 with an agonist would appear to be a fruitful pathway to develop new treatments for anaphylactic events and allergy sufferers.

SHIP1 knockout mice also develop a severe inflammatory disease in their small intestine that closely resembles human Crohn's disease.90 There is a paucity of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the lamina propria of SHIP1 knockout mice with Treg cells being found at normal numbers, suggesting this inflammatory disease does not result from an autoimmune T cell attack, but rather results from a lack of T effector cells, culminating in an over-response by the SHIP-deficient neutrophil compartment.90 These results suggest a positive role for SHIP1 in promoting trafficking and/or persistence of T-cells at mucosal sites.10 Thus, SHIP1 could potentially be a genetic determinant of susceptibility to Crohn's disease in humans. Consistent with this hypothesis, there are single nucleotide polymorphisms found at 2q37 in the human genome, where the human SHIP1/INPP5D gene is located, that are highly enriched in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis patients.91 Studies are continuing, but these results may have important implications for patients with all forms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Other evidence suggests that SHIP1 agonists may also be used to treat common gastrointestinal problems such as diarrhea caused by certain bacteria.92 With the development of small molecule SHIP modulators, studies to determine the role of SHIP in a number of intestinal and pulmonary ailments appear to be a prime area of future research.

3. Bone Marrow Transplantation

SHIP1 antagonists may also have therapeutic potential in averting Graft-versus-Host-Disease (GvHD).78,93,94 This ameliorative effect has a profound significance in bone marrow transplantation, which constitutes a major treatment option for various cancers and genetic disorders.93 Unfortunately, serious complications exist with bone marrow transplants due to the high risk of GvHD and also because of poor engraftment and consequently graft failure. GvHD is the leading cause of treatment related mortality in bone marrow transplant recipients and is mediated by donor T cells that attack host tissue. Sprent and colleagues showed that antigen presentation by the host could trigger GvHD.95 Using more modern tools, a direct role for host dendritic cells in priming GvHD after allogeneic bone marrow transplant was shown by Shlomchik.96 This work has been confirmed and extended by others to show that major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II expression by the host epithelium is not sufficient to prime acute GvHD.97 Myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSC) cells are now appreciated to be the major mediators of immune suppression during intense immune responses.98 A 10- to 20-fold expansion of MDSC cells in SHIP knockout mice protects them from GvHD in the setting of T cell replete allogeneic bone marrow transplantation.93,94

The dramatically weakened allogeneic T cell response in SHIP1-deficient mice greatly contributes to the ability of these mice to abrogate GvHD, which heavily depends on the activity of donor T-lymphocytes. Normally, donor T cells are activated upon exposure to host antigen-presenting cells expressing MHC antigens.93 Once activated, the donor T cells then initiate a series of events which leads to the death of host cells, which cumulatively then gives rise to GvHD. SHIP1 deficiency, however, suppresses this chain of events. In fact, induction of SHIP1 deficiency in adult mice prevents acute and lethal GvHD after a T cell-replete, MHC-mismatched bone marrow transplant.94 In addition, SHIP1 deficiency suppresses acute rejection of MHC class I mismatched bone marrow grafts.78,99 Paraiso et al. have shown that this protection could be achieved by induction of genetic SHIP1-deficiency for a brief period prior to T cell replete MJC class I mismatched bone marrow transplantation, thereby preventing the onset of GvHD in the transplant recipients.94

SHIP1 inhibition may also play a role in limiting GvHD because of the enzymes regulation of T regulatory (Treg) cells. Treg cells limit deleterious allogeneic T cell responses that cause GvHD, including host Treg cells that can, in addition, promote engraftment of allogeneic bone marrow cells.100-103 In fact, Treg cells can reduce GvHD without compromising the beneficial effects of donor T cell mediated graft-versus-tumor effects post-transplant.101 SHIP1 not only limits intrinsic signaling that leads to the development and formation of Treg cells in the periphery, but also limits the extrinsic effects of myeloid cells that promote Treg formation.104,105 As SHIP1 expression by the host is necessary for efficient rejection of allogeneic bone marrow and cardiac grafts42,78,99,104 and the GvHD that compromises post-transplant survival,78,93 inhibition of SHIP1 could be protective of the host during a bone marrow transplant.78

Inhibition of SHIP1 with a small molecule could therefore be used to prevent rejection of HLA mismatched hematopoietic stem/progenitor grafts and reduce GvHD. Rejection of MHC-I mismatched BM grafts can be mediated by NK cells106 and is prevented or reduced by both host and donor Treg cells.103,107,108 Thus, the multi-modal facilitation of allogeneic BM transplant by SHIP inhibition could be a consequence of the diversity in activating or inhibitory roles that SHIP1 plays in NK cell function (activating),78 MDSC homeostasis (inhibitory),93,94 Treg homeostasis (inhibitory) and acquisition of FoxP3 expression by naïve T cells (inhibitory).11,104,105

4. Anemia, Thrombocytopenia and Neutropenia

Inhibition of SHIP1 in healthy cells leads to an increase in PI(3,4,5)P3, resulting in an increase in the amount of cell division and/or survival specific to blood cells and other cells of the hematopoietic lineage. Treatments to increase blood cell production currently rely on the recombinant endogenous growth factors Erythropoietin (EPO) and G-CSF (Neupogen), which are protein-based and therefore must be injected, as they are decomposed by the stomach when given orally. These growth factors only promote red blood cell (RBC) and granulocyte production without having a significant impact on platelet numbers. Typically neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and anemia are problematic side effect of cancer chemotherapy, so SHIP1 inhibitors could be used to facilitate this form of cancer treatment.11 Radiation poisoning also leads to similar blood cell nadirs, so SHIP1 antagonists may be useful for the treatment of accidental radiation exposure.109,110 A small molecule SHIP1 inhibitor could have the advantage of treating anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia simultaneously and possess oral availability. Studies with a selective SHIP1 inhibitor recently showed that RBC counts were preserved and neutrophil and platelet counts rebounded faster in myeloablated mice treated with the SHIP1 inhibitor as compared to vehicle controls.26 Recent studies have found that SHIP inhibition in the setting of myeloablation also promotes faster rebound of lymphocytes and white blood cells.111 The enhanced recovery mediated by SHIP1 inhibition is pan-hematolymphoid suggesting there may be effects of SHIP inhibition directly on the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) compartment and/or on the niche cells that sustain HSC. Indeed, there is a strong likelihood for both.11 SHIP1 as well as a stem cell specific isoform of SHIP1 (s-SHIP) are expressed by HSC.112 In addition, mesenchymal stem cells and osteoblasts that support HSC also express SHIP1.12,30 Studies of SHIP1 mutant mice have revealed a complex role for SHIP1 in HSC homeostasis, self-renewal and mobilization with effects of SHIP1 on both BM retention, self-renewal and homeostasis. Future studies with SHIP inhibition are clearly merited to determine if inhibitors can be used to mobilize HSC for transplant or to promote engraftment of HSC and possibly even MSC, by treatment of hosts or stem/progenitors prior to transplant.

5. Diabetes

Dysfunctional insulin signaling often leads to diabetes mellitus. Type 2 diabetes is especially becoming a continuously growing global health issue. As a result, components of the insulin signaling pathway, including SHIP2, are considered important targets for the discovery of new therapeutic agents.113 SHIP2 has been shown to be an important negative regulator of the insulin-signaling pathway, and therefore its inhibition should lead to increased insulin sensitivity.35,114 The role of SHIP2 in insulin signaling has been tested using several techniques, with exciting and sometimes controversial results.

SHIP2 knockout mice would seem to provide the clearest test system for the effect of SHIP2 on insulin signaling. One strain, generated by Clement et al., was reported to suffer severe neonatal hypoglycemia and death within three days.35 However it came to light that a second gene, Phox2a, was also inadvertently deleted in these mice. As Phox2a may influence insulin signaling, it remains unclear which gene deletion led to the observed phenotype. More recently, this group developed a new mutant mouse with a catalytically inactive form of SHIP2.115 These mice were viable and showed some defects in the development of muscle, but normal glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity and insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation was demonstrated in this strain, casting doubt on the role SHIP2's catalytic activity plays in these processes.

Other studies by Sleeman et al. generated a strain of SHIP2 knockout mice that are viable and have a typically reduced body weight despite increased food intake.36 Placing these SHIP2 knockout mice on a high-fat diet showed that they were almost completely resistant to weight gain over a 12-week period. Over this time period the mice exhibited no increase in serum lipids and did not develop hyperglycemia or hyperinsulinamia. These results are attributed to enhanced insulin-stimulated Akt and p70S6K activation in the liver and skeletal glucose when compared to normal mice.

Evidence of the benefits of SHIP2 expression in diabetes was also obtained using antisense nucleotides to lower SHIP2 expression in rodents. These treatments reduced SHIP2 messenger RNA and caused a rapid improvement in muscle insulin sensitivity in a rat obesity model.116,117 A number of other studies using RNAi have also been reported, but their results are somewhat conflicting.118-121 This may be due to variations in the model systems and/or differences in the methodology used in these experiments.

SHIP2 has also been implicated in the clinical pathology of diabetes in humans. Studies of polymorphisms between populations from Belgium and the UK showed that a modification of the SHIP2 gene was more frequently found in type 2 diabetic patients.122 This study was confirmed in a rodent model, which noted increased levels of SHIP2 in skeletal muscle of diabetic mice.123 Similar studies of populations in Europe and Japan also noted that changes in the SHIP2 gene corresponded with diabetes and metabolic syndrome.124-126 Despite mixed results in several biological systems, given the results from human population studies interest in SHIP2 as an emerging target for new diabetes therapies appears to be on the rise.

6. Atherosclerosis

Endothelial cell dysfunction and apoptosis have been shown to be key early events leading to cardiovascular disease. Typically these events are controlled by serum lipoproteins. A recent report by DeKroon127 suggests SHIP2 may play a role in atherosclerosis by influencing apoptosis in endothelial cells. This work indicated that SHIP2 is a key factor in regulating the apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) allele, where the APOE4-very low density lipoproteins (VLDLs) inhibited Akt phosphorylation by reducing levels of PI(3,4,5)P3 through SHIP2. The authors explain these results by proposing a model where the PI3K pathway influences lipoprotein modulation. In this model HDL binds the SR-BI scavenger receptor and then mediates activation of the S1P3 receptor, enhancing PI3K/Akt activity, which then suppresses caspase activity. APOE4-VLDL opposes this signaling by binding to a nearby LDL receptor, with this complex subsequently recruiting SHIP2 to the SR-BI receptor resulting in lowering of the concentration of PI(3,4,5)P3 and a downregulation of Akt activity, increasing caspase activity. RNAi studies supported this model and showed that inhibiting SHIP2 expression increased the activity of caspase 3 and caspase 7, the two primary caspases implicated in the development of cardiovascular disease. While further investigation is obviously needed, these results demonstrate that SHIP2 may be a pharmacological target for the treatment of cardiovascular disease.

7. Alzheimer's and Neurodegenerative diseases

An interesting coincidence is that the APOE4 allele is a significant genetic risk factor for the eventual development of Alzheimer's disease.128 In addition, the loss of function of caspase 3, which is the predominant caspase involved in the cleavage of the amyloid-beta 4A precursor protein, is often associated with neuronal death in Alzheimer's disease. Given that SHIP2 is highly expressed in the brain,129 demonstrated regulation of caspase 3 by SHIP2 may play a role in Alzheimer's and other neurodegenerative diseases,127 a link that has been previously hypothesized.8 A second relationship between Alzheimer's disease and SHIP2 is implied from recent studies showing a link between the disease and insulin resistance, where hippocampal brain slices in Alzheimer's patients were less responsive to insulin than controls.130 This lack of response was attributed to increased phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) that attenuated downstream Akt and ERK signaling. The authors comment that insulin resistance in the brain in Alzheimer's disease was not dependent on diabetes, or on the APOE4 genotype. As SHIP2 knockout mice have no obvious neuronal defects, and with the role SHIP2 plays in insulin resistance, future studies on SHIP2 inhibitors in Alzheimer's disease appears to have interesting therapeutic implications.

The PI3K pathway has also been shown to play a role in regulating neuronal differentiation, which is critical for the formation and preservation of neuronal networks. For example, the establishment of axon/dendrite polarity has been shown to be dependent on PI3K signaling.131 Additionally, activation of PI3K signaling with nerve growth factor (NGF) resulted in phosphorylation of GSKβ, which became inactive and promoted neurite elongation.132 Using shRNA, downregulation of the SHIP2 gene elevated NGF-induced PI(3,4,5)P3 accumulation and increased the number and length of neurites in PC12 cells. This indicates a role for SHIP2 in regulating both neurite elongation and budding, where aberrant behavior may play a role in neurodegenerative diseases.

III. Small Molecule Phosphatase Modulators

The inositol phosphatases are appealing targets for pharmaceutical intervention,7,8,133,134 as the events these enzymes modulate are near the origin of the cellular signal, which can be stopped or started with a smaller number of molecular interactions. The enzymes in the PI3K/PTEN/SHIP cassette are also the first soluble enzymes in the signal transduction pathway, and therefore the difficulties of working with membrane proteins are circumvented. Given the significant effects that changing the expression and activity of inositol phosphatases have on numerous biological pathways, modulating these enzymes with small molecules is of great interest. Efforts have become focused on the development of small molecule agonists of SHIP1 as well as antagonists for SHIP1 and SHIP2.

1. SHIP1 Agonists

As SHIP1 opposes PI3K signaling, and overactive PI3K activity has been shown to facilitate tumor growth, the exploration of SHIP1 agonists as potential new cancer drugs has become an appealing area of medicinal research. To find SHIP1 agonists, researchers from the Andersen and Krystal groups at the University of British Columbia screened crude extracts of marine invertebrates. In this initial screening the naturally occurring sesquiterpene pelorol (1) was found to enhance SHIP1 activity (Figure 4).135 This molecule was reported to show approximately 2-fold activation of SHIP1 at a concentration of 5μg/mL. Pelorol was isolated from a marine sponge, Dactylospongia elegans, in Papua New Guinea. Since only small amounts of pelorol could be obtained from D. elegans, a synthetic route to this molecule was also developed. This route allowed for the synthesis of the natural product in 9 steps from the commercially available terpenoid (+)-sclareolide.135 Pelorol had been isolated independently by Konig136 and Schmitz137 in 2000 from D. elegans and the Micronesian sponge Petrosaspongia metachromia, respectively, but the molecule's enzymatic target was undetermined.

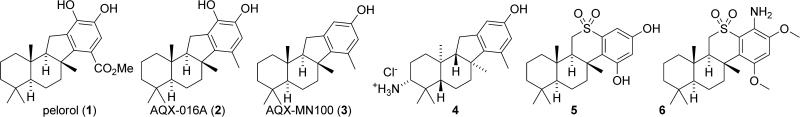

Figure 4.

Pelorol and analogs.

Several analogs of pelorol were synthesized and tested for SHIP1 activity.135,138 This study led to the discovery of tolyl analogue 2 (AQX-016A), which exhibited improved biological activity.135 For example, at 2μM AQX-016A (2) demonstrated a 6-fold acceleration of SHIP1 mediated dephosphorylation of Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 in vitro, as compared to pelorol which showed a 2-fold acceleration at the same concentration.139 Yang et al. synthesized methyl agonist 2 starting from (+)-sclareolide through a series of 6 steps with an overall yield of 29%.135 The tolyl analogue 2 was shown to inhibit degranulation and TNFα production in SHIP1+/+ murine mast cells stimulated with IgE. However, it exhibited no activity in SHIP1–/– murine mast cells, suggesting that agonist 2 selectively targets SHIP1. Additional studies with SHIP2 showed that 2 preferentially activates SHIP1 over SHIP2 in vitro by at least a factor of five.139 Further testing with 2 shows similar anti-inflammatory effects to that of dexamethasone (a reference standard) in murine models of ear edema and sepsis syndrome.135 The appeal of AQX-016A was diminished by the presence of its catechol moiety, which may cause problems in vivo. Catechols are typically undesired in medicinal compounds because they can produce unwanted side effects that are independent of their specific protein pocket binding interactions. Some examples of these side effects include metal binding and oxidation to an orthoquinone. Orthoquinones are especially poor pharmaceutical candidates because they can covalently modify proteins and DNA through Michael reactions, leading to undesired toxicity.139

This issue was addressed by removing the hydroxyl functionality at C17 to form a modified version designated as AQX-MN100 (3).136,139 Analysis of AQX-MN100 biological activity showed that its potency is equivalent to that of the diol AQX-016A (a 6-fold acceleration of SHIP1 activity at 2μM). Furthermore, similar to tolyl analogue 2, AQX-MN100 (3) preferentially activates SHIP1 over SHIP2. Initial toxicology studies provided evidence that AQX-MN100 was well tolerated and did not have a large impact on peripheral blood cell counts, bone marrow progenitor numbers, liver function, and kidney function. In 2009, Kennah et al. showed that AQX-MN100 (3) was active in several in vitro assays against multiple myeloma.71 This antineoplasic effect was traced back to the activation of SHIP1. Consistent with the molecule's selective SHIP1 activity, phenol 3 displays no significant effects on SHIP1-deficient non-hematopoietic cells. Furthermore, AQX-MN100 activation of SHIP1 significantly increased the effects of the anti-inflammatory steroid dexamethasone. AQX-MN100 also showed synergistic effects with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, slowing the rate of proliferation of OPM2 multiple myeloma cells as measured by [3H]-thymidine uptake.71 As bortezomib is a common cytotoxic drug used to fight multiple myeloma, this corroborates the theorized potential of small molecule SHIP1 agonists to be used as treatments for cancer, especially hematopoietic malignancies.

Additional studies by Aquinox Pharmaceuticals have resulted in the development of even more pelorol-based SHIP1 agonists. One focus appears to be increasing the water solubility of these terpene-based structures, leading to the development of amine containing structures like 4, which was only slightly less active than AQX-MN100 (3).138 Unexpectedly, this molecule contains the enantiomeric configuration of the terpenoid structure as compared to pelorol, with the analog possessing the same configuration as pelorol having a weaker effect on upregulating SHIP1. Overall the incorporation of the amine significantly enhanced water solubility without significantly effecting the molecule's activity as an agonist.

The analog studies appear to have culminated in the development of sulfone containing derivatives such as 5 and 6, which were recently disclosed in the patent literature.140 These molecules are readily synthesized from (+)-sclareolide and are less lipophilic than the previous pelorol based analogs, which improves their pharmacodynamic properties and oral availability. Sulfone 5 showed the highest activity in SHIP1 agonist assays, while aniline 6 showed the best activity in the OPM2 multiple myeloma cell assay. No in vivo data against multiple myeloma was presented; however some in vivo anti-inflammatory data (specifically in vivo assays on passive cutaneous anaphylaxis in rats and carrageenan paw edema in mice) was given. The data presented in this patent disclosure is incomplete since information for enhancement of SHIP1 activity is given for only a subset of compounds. The given data is also presented in a qualitative format, so little conclusion can be made about structure activity relationships in this series.

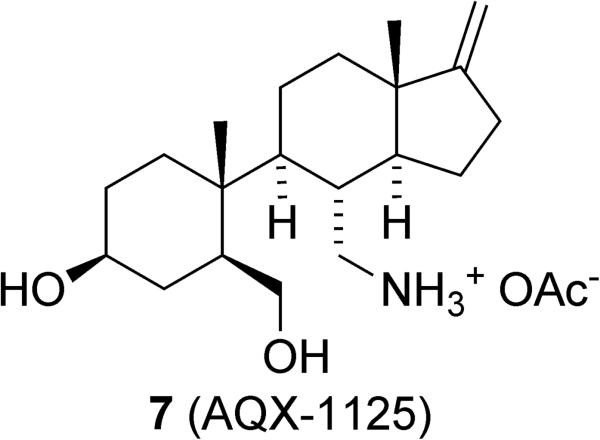

Aquinox Pharmaceuticals recently initiated clinical trials using the SHIP1 agonist AQX-1125 (7), which is being evaluated to treat airway inflammation (Figure 5).141,142 This compound is not related to pelorol (1), but instead appears to be an aminosteroid derivative with an open B ring. While the genesis of this compound is not discussed, it appears to have been found from screening a number of indene derivatives that were synthesized by Inflazyme Pharmaceuticals as analogs of the natural product contignasterol.143 AQX-1125 caused an ~20% increase in SHIP1 activation at 300μM. The molecule was also effective at inhibiting cytokine release in vitro, which modulated the immune response. Tissue distribution studies showed that AQX-1125 is present at high concentrations in the lungs and pharmacokinetic studies showed that the molecule possesses good oral availability.141 AQX-1125 was effective at treating pulmonary inflammation in mice in a number of assays.142 Should these results be replicated in human trials, AQX-1125 shows excellent potential as the first pharmaceutical that specifically targets SHIP1.

Figure 5.

The indene AQX-1125.

The discovery of these small molecule agonists of SHIP1 also contributed to the identification of SHIP1 as an allosterically activated enzyme. Classical enzyme kinetic analysis of SHIP1 agonists verified their sigmoidal reaction kinetics, a characteristic of allosteric enzymes. Furthermore, both AQX-MN100 and SHIP1's end product, PI(3,4)P2, enhance SHIP1's activity and bind to the C2 domain of SHIP1, as confirmed by scintillation proximity assays. These combined findings strongly implicate SHIP1 as an allosterically regulated enzyme.

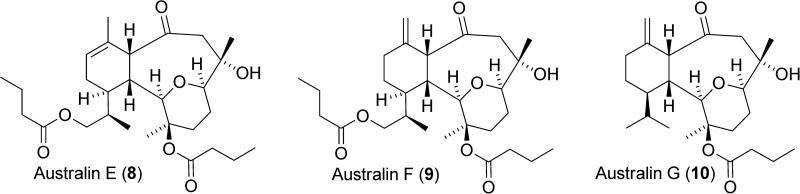

An isolate from the soft coral Cladiella sp. collected in Pohnpei was also shown by Andersen and Mui to activate SHIP1.144 The isolate was fractionated and the structure of the active constituent determined by x-ray diffraction. This led to the determination that australin E (8) was the SHIP1 agonist present in the isolate (Figure 6), with the molecule showing an approximately 12% increase of SHIP1 activity at 100μM. Australin E shows little resemblance to the pelorol-based agonists, with the structure belonging to the eunicellin diterpenoids. While the eunicellin diterpenoids have shown in vitro cytotoxicity against cancer cell lines, this is the first example of a SHIP1 agonist in this class of natural products. Three other australin analogs were also identified from the isolate, but showed no agonistic activity for SHIP1. These included australin F (9) and G (10), which implicates the endocyclic alkene as important for biological activity.

Figure 6.

Australin E, F and G.

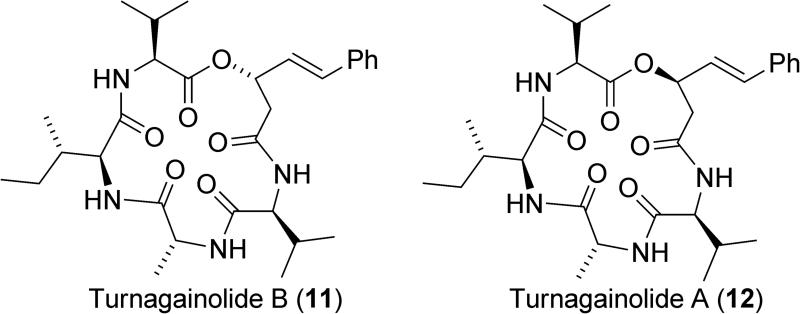

Cyclic depsipeptides have also been shown to have the ability to activate SHIP1, defining another structural class of SHIP1 agonists (Figure 7).145 These agonists were isolated from a strain of Bacillus sp. that was cultured from a sediment sample collected from the sea floor. The structures of these molecules were verified by synthesis of the linear seco acids followed by macrocyclization with a carbodiimide reagent. Turnagainolide B (11) was found to have similar potency as a SHIP1 activator to AQX-MN100, showing a 12% increase in SHIP1 activity at 10μM. Interestingly, turnagainolide A (12), which only differs in the stereochemistry of the lactone, was found to have no activity as a SHIP1 agonist.

Figure 7.

The turnagainolides.

2. SHIP1 Antagonists

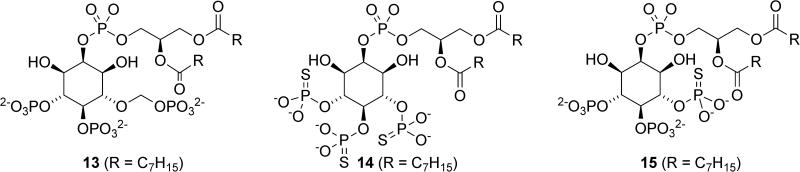

Several SHIP1 antagonists have also been identified. The Prestwich laboratory designed several metabolically stabilized analogues of PI(3,4,5)P3 as probes to better understand the role of this lipid in cell physiology (Figure 8).17 While very similar to PI(3,4,5)P3, these compounds contain a phosphorthioate or a methylenephosphonate instead of a phosphate group at the 5’ position of the inositol, which inhibits hydrolysis. These molecules were evaluated for their ability to inhibit SHIP1 and SHIP2 in the hydrolysis of radiolabelled Ins(1,3,4,5)P4, with compounds 13, 14 and 15 showing approximately 50% inhibition of SHIP1 at 10μM concentration. PI(3,4,5)P3 analogues 13-15 also inhibit SHIP2 to some extent, highlighting the similarity of the inositol binding pockets of the two enzymes. No inhibition of PTEN was observed. Interestingly, similar inositols with a phosphorthioate or a methylenephosphonate at the 3-position also showed modest activity as inhibitors of SHIP1.

Figure 8.

Metabolically stabilized analogs of PI(3,4,5)P3.

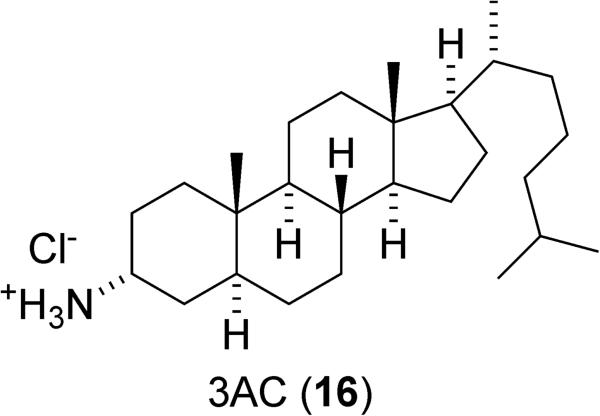

Using a high-throughput screening approach, Brooks et al. identified 3α-aminocholestane (3AC, 16) as a SHIP1 inhibitor (Figure 9).26 This aminosteroid displays a detectable level of inhibition at 2 μM and 50% inhibition at 10 μM. 3AC did not show any inhibition of SHIP2 or PTEN at this concentration. Further analysis of 3AC's biological activity demonstrated that it expands the myeloid immunoregulatory cell pool, suppresses priming of allogeneic T cell responses in peripheral lymphoid tissues such as the spleen and lymph nodes, speeds the recovery of granulocyte and platelet production, and significantly sustains red blood cell numbers in myelosuppressed hosts. These results all mirror the effects observed in SHIP knockout mice.34 Consistent with the “Two PIP Hypothesis”, 3AC was shown to reduce the growth and survival of hematopoietic cancer cells, including the AML cell line KG-1 and murine C1498 leukemia cells with an IC50 of approximately 10μM. Control experiments verified that this decrease in cell viability was due to the inhibition of SHIP1. Specifically, C1438 cells incubated with high concentrations of the product of the SHIP reaction (PI(4,5)P2) were protected against 3AC induced apoptosis, while cell viability was still significantly decreased by 3AC when other inositol bisphosphates were utilized.26 The specific binding site of this inhibitor has not been determined; it may be binding at the active site of the enzyme or the allosteric site where agonists like 1 and 4 are thought to interact with the enzyme.139 Dosing 3AC in mice did not result in the typical myeloid lung infiltration, splenomegaly, and shortened life span observed in SHIP1 knockout mice.26,34 In fact, mice treated with 3AC are generally healthy and do not seem to exhibit any detrimental physiologies, including the pneumonia and Crohn's like ileitis often observed in SHIP1 knockout mice.26

Figure 9.

The aminosteroid SHIP1 inhibitor 3AC (16).

Since cancer is a heterogeneous disease, the effects of 3AC were evaluated on three common multiple myeloma cell lines (U266, RPMI8226 and OPM2) to determine if each line would be equally affected by the SHIP1 inhibitor.27 While treatment of OPM2 cells with 3AC led to apoptosis, the less proliferative RPMI8226 and U266 cells appeared to manifest their lack of viability through an autophagic process. In RPMI8226 and U266 cells, exposure to 3AC for 48 hours also led to degradation of the SHIP1 protein, but not SHIP2 or PTEN. Responding to 3AC treatment with autophagy may protect cells in the short term from 3AC treatment, but autophagy can progress to apoptosis should the cellular stress be prolonged.

Treatment of multiple myeloma with 3AC in vivo, employing a tumor xenograft mouse model and OPM2 cells, was also explored.27 Dosing mice that were challenged with OPM2 cells by intraperitoneal injection with 3AC (60μM injected in the intraperitoneal space once a day for 7 days followed by a biweekly dose for the ensuing 15 weeks) resulted in reduced tumor growth and reduced numbers of OPM2 cells in the blood stream. More significantly, mice treated with 3AC were shown to survive significantly longer after the tumor challenge than control mice. Evaluation of the tumor cells from mice that resisted treatment showed a significant upregulation of SHIP2, suggesting a paralog compensation mechanism of resistance where SHIP1 inhibition acts as a selection pressure favoring tumor cells that can compensate with an increase in SHIP2 expression. These results suggest that complementing SHIP1 inhibitors with SHIP2 inhibitors may be an even more effective treatment regime for multiple myeloma. Alternatively, the tumors could be targeted with molecules that inhibit both SHIP paralogs (pan-SHIP1/2 inhibitors).

3. SHIP2 Antagonists

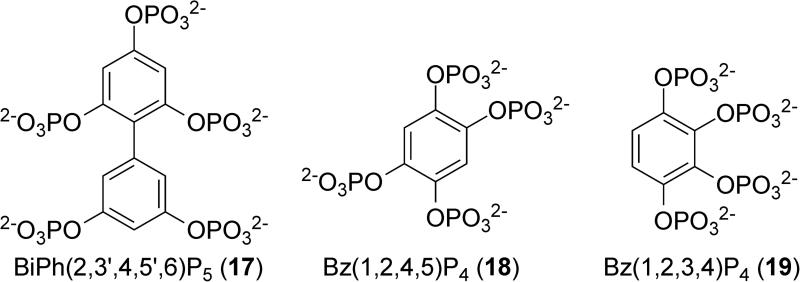

Phosphorylated polyphenols like 17, 18 and 19 (Figure 10) have been shown to be effective inhibitors of SHIP2.146 These compounds were investigated when three-dimensional modeling revealed a high homology between the phosphorylated phenols and phosphorylated inositol substrates. The number of phosphates and the position of the phosphates on the aromatic core greatly influenced SHIP2 inhibition. For example, Bz(1,2,4,5)P4 (18) showed an IC50 of 11.2 μM, while Bz(1,2,3,4)P4 (19) showed an IC50 of 19.6 μM. None of the phosphorylated phenol inhibitors appeared to be acting as a substrate for the phosphatase, but the results did appear to be consistent with a competitive inhibitor. The most active phosphorylated polyphenol SHIP2 inhibitor was biphenyl(2,3’,4,5’,6)P5 (17), which demonstrated an IC50 of 1.8 μM. While no data on the selectivity of inhibition with respect to SHIP1 or PTEN was provided, these inhibitors did inhibit Type-I Ins(1,4,5)P3 5-phosphatase, which is another inositol 5-phosphatase. Given the highly polar structure of the phosphorylated phenols, it is unlikely that they can enter cells in an unmodified form. While the authors do mention protecting the phosphate groups to create cell permeable analogs, no structures have yet been disclosed.

Figure 10.

Phosphorylated polyphenol SHIP2 inhibitors.

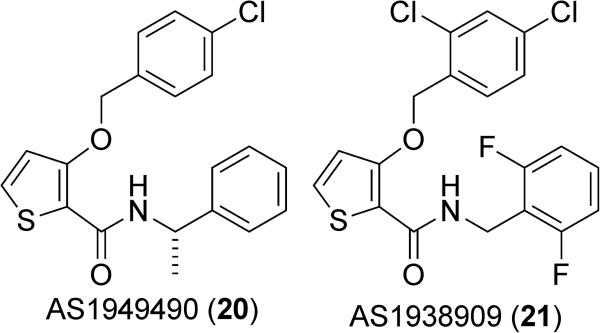

A thiophene-based small molecule inhibitor of SHIP2, AS1949490 (20) (Figure 11) was disclosed by Suwa et al. at Astellas Pharmaceuticals.113 This molecule was reported to have an IC50 value of 0.62 μM against SHIP2 and was selective for SHIP2 compared to SHIP1 (IC50 against SHIP1 of 13 μM). Treatment of L6 myoblasts with AS1949490 led to the increased phosphorylation and subsequent activation of Akt. Interestingly, this inhibitor affects only protein kinase B2 (Akt2), an isoform of Akt that plays an especially predominant role in insulin signaling, while it has very minimal, if any, inhibitory effects on protein kinase B1 (Akt1).147 In addition, AS1949490 was shown to increase glucose metabolism, resulting in an increase in both glucose uptake and consumption. A rat hematoma cell line derived from H35 cells (FAO) treated with 20 displayed reduced insulin-dependent gluconeogenesis and underexpression of related genes. Similarly, normal adult mice treated with 20 also showed reduced gluconeogenesis in the liver, demonstrating that AS1949490 can control gluconeogensis both in vitro and in vivo. Diabetic db/db mice chronically treated with 20 displayed increased stimulation of insulin signaling through increased phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β). These mice showed a 37% reduction in fasting blood glucose as compared to vehicle controls.113 The physiological effects of AS1949490 clearly demonstrate the importance of SHIP2 in the regulation of insulin signaling.

Figure 11.

Thiophene-based SHIP2 inhibitors.

Later efforts by the Astellas group led to the development of a second thiophene based inhibitor, AS1938909 (21) (Figure 11).148 This compound was reported to have a similar affinity for SHIP2 as AS1949490 20 (IC50 of 0.57 μM), as well as a greater selectivity for SHIP2 over SHIP1 (IC50 for SHIP1 of 21 μM). Administration of AS1938909 was shown to increase Akt phosphorylation, glucose consumption and glucose uptake in L6 myotubes. Longer administration of AS1938909 was also found to alter gene expression patterns, specifically upregulating the GLUT1 gene but not GLUT4. GLUT1 is a glucose transporter, typically localized on or near the cell surface, which has a significant role in basal glucose uptake and has been linked to the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. These studies were all performed in cell culture, but still demonstrate the potential of SHIP2 inhibition for the treatment of diabetes at least in mice. Some researchers have claimed that the insulin-sensitizing effects of these compounds may be difficult to reproduce.115 No data was given to support these findings, however, and a more recent report seemed to have no issue observing the effects of AS1949490 on the insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with TNFα.149 For these lead molecules to proceed further, analogs will need to be prepared with better solubility properties so that dosing can be performed orally, as the thiophenes show poor pharmacokinetic properties and have limited cell permeability.8

Recently, the crystal structure of a truncated, catalytically active form of SHIP2 was solved bound to biphenyl(2,3’,4,5’,6)P5 (17).150 The unit cell contained two associated SHIP2 monomers, but only one of the enzymes had the inhibitor bound in the binding pocket. The inhibitor also had additional interactions with residues of a second SHIP2 molecule that was present in the crystal lattice. As SHIP2 is normally not present in high concentrations, these interactions with a second molecule of SHIP2 are likely not important in understanding the binding of the inhibitor to the active site. In order to gain a greater understanding of the interaction between SHIP2 and the inhibitor, molecular dynamics calculations were performed after removing the second SHIP2 molecule. The simulations revealed a loop of the protein that acts as a P4-interacting motif (P4IM). This portion was disordered and located above the binding site in the crystal structure but during the dynamics calculation this flexible region moved to interact with the inhibitor and became part of the binding pocket. Evaluation of the sequence alignment of 10 human inositol 5-phosphatases showed that only SHIP1 and SHIP2 possessed this flexible loop P4IM motif. Molecular modeling was then performed to evaluate the binding of di-C8-PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and AS1949490 (20). This work provides a very important advance, as now that the enzyme binding pocket has been described, drug discovery can move forward in a more rational manner. Given the high homology between SHIP1 and SHIP2, this structure may also allow researchers to design new SHIP1 inhibitors.

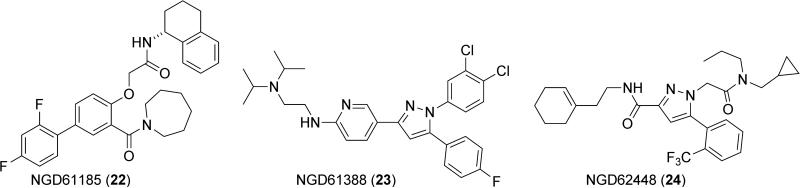

Other heterocyclic SHIP2 inhibitors were discovered by a novel type of high throughput screening involving mass spectroscopy by Neogenesis Pharmaceuticals.151 The publication presents a number of these inhibitors, with some active molecules being shown in Figure 12. One of these compounds (NGD61185, 22) bears a strong resemblance to the molecules investigated by Astellas, as its phenol-based core is similar to the thiophene inhibitors of the Astellas compounds. The other two inhibitors possess highly functionalized pyrazole core structures. The most active compound mentioned in the paper is NGD78700 (Kd = 0.82 ± 0.14 μM), but the structure of this material is not revealed, and most other experiments are performed with NGD61338 23. NGD61338 is quite active, with a reported IC50 of 1.1 μM against SHIP2. Kinetic analysis of NGD61338 binding to SHIP2 showed that binding of the inhibitor was mutually exclusive with PI(3,4,5)P3 analogs, which suggests that NGD61185 is binding at the active site of the enzyme. No data is given on the selectivity of these inhibitors with regard to other phosphatases. The effects of these compounds in cells and their bioavailability also remain to be investigated, as well as in vivo studies on toxicity.

Figure 12.

SHIP2 inhibitors reported by Neogenesis Pharmaceuticals.

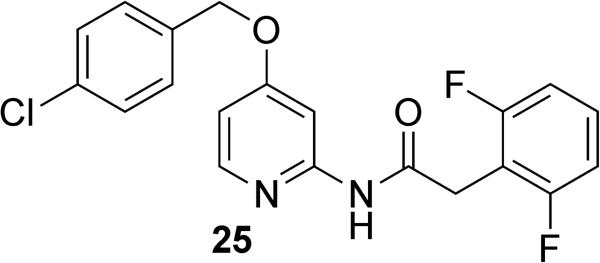

Working from the structures discovered by Astellas and Neogenesis, researchers at the University of Toyama and Kitasato University developed new SHIP2 inhibitors based on a pyridine scaffold (Figure 13).149 These inhibitors were designed by a computational approach taking advantage of ligand-based drug design. By using the structures of the Neogenesis and Astellas inhibitors as a template, pyridine-based structures were developed that held the relevant hydrogen bonding functionality and aromatic groups in what was thought to be the biologically relevant conformation necessary for SHIP2 inhibition. The most active of the molecules developed in this manner was pyridine 25. While no data on inhibition of SHIP2 was reported with 25, in vitro evaluation of the molecule in 3T3-L1 adipocytes showed a decrease in insulin-induced phosphorylation of Akt. Further evaluation in mice showed a decrease in fasting glucose levels along with a trend of decreased insulin resistance. While the dosing level was high (dosed orally at 300mg/kg), these results appear to support the inhibition of SHIP2 by pyridine 25.

Figure 13.

Pyridine based SHIP2 inhibitor 25.

Other SHIP2 inhibitors are almost certainly known behind the closed doors of pharmaceutical companies. For example, workers at Amgen reported a high-throughput microfluidic assay to screen for inhibitors of SHIP2. This assay was conducted using a 91,060 compound library, with over 700 inhibitors being identified as having ≥70% inhibition of SHIP2 at 25μM.152 One compound was claimed to have an IC50 of 0.37 μM against SHIP2, and also showed significant activity against SHIP1 and PTEN (IC50 = 0.90 μM against SHIP1 and 2.2 μM against PTEN). Unfortunately, no chemical structures have been reported and no other follow-up studies have been published on these inhibitors. Over time these compounds may become known when either clinical trials begin or when the research program is closed. In either case, it may be many years before these structures and the results of these studies on SHIP2 inhibitors become known.

4. Pan SHIP1/SHIP2 Inhibitors

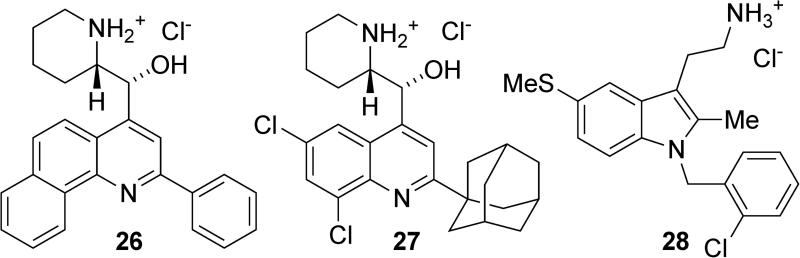

High throughput screening efforts in the Kerr group also led to the discovery of several structures that inhibit both SHIP1 and SHIP2.27 These inhibitors included the two quinoline aminoalcohols, 26 and 27, and tryptamine 28 (Figure 14). Quinolines 26 and 27 completely inhibited SHIP1 activity at 100μM, while tryptamine 28 showed approximately 70% inhibition at this concentration. Against SHIP2, quinoline 26 showed approximately 60% inhibition at 100μM, while quinoline 27 showed 90% inhibition and tryptamine 28 showed 50% inhibition at the same concentration. These compounds did not show inhibition of OCRL, another human inositol 5-phosphatase, suggesting that the molecules are not general phosphatase inhibitors but have some specificity towards the two SHIP paralogs. All three of these molecules showed activity against the multiple myeloma cell lines RPMI8226, U266 and OPM2. Cell cycle studies showed significant arrest at the G2/M phase in all cell lines along with a significant increase in sub-G0-G1 phase cells. Typically these results are an indication of apoptotic cell death. Breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7) were also evaluated, as SHIP2 is overexpressed in a significant number of breast carcinomas.72-75 These breast cancer cell lines do not express SHIP1, and therefore the selective SHIP1 inhibitor 3AC (16) had no effect on these cells. In contrast, cell viability was severely reduced in both breast cancer cell lines with increasing concentrations of the pan SHIP1/2 inhibitors above 5μM. To further prove that SHIP2 inhibition was responsible for the observed cell death, exogenous PtdIns(3,4)P2-diC16 was added to rescue cells from the effects of the pan-SHIP1/2 inhibitors. For each inhibitor, these add-back experiments improved cell survival, but no change was seen when PtdIns(3,4)P2-diC16 was used, providing further evidence that the SHIP2 inhibition was responsible for the reduced cell viability.

Figure 14.

Pan-SHIP1/2 inhibitors.

IV. Conclusion and Outlook

Many studies have demonstrated the importance of SHIP in a range of disease states, including cancer, diabetes, bone marrow transplantation, allergy and other inflammatory disorders. Questions remain, however, about the specific molecular interactions and mechanisms through which these enzymes modulate these conditions. Complicating these studies are the ability of these phosphatases to hydrolyze multiple substrates and/or act in a scaffolding role, making it difficult to determine which functions are most important for in vitro activity. Additionally, some inositol phosphatases (like SHIP) act as both initiators and terminators of cell signaling, making it difficult to delineate which events are important in a given illness. Small molecule inositol phosphatase modulators have therefore been receiving significant attention, as these molecules provide alternative tools to probe the relevant cellular signaling pathways. Both agonists and antagonists of SHIP1 have been developed, with inhibitors of SHIP2 and pan-SHIP1/2 inhibitors also being discovered in the last few years. While the modulation of the phosphatases of this pathway remain in their infancy when compared to PI3K inhibitors, initial results show great promise. In the future, more potent and soluble molecules will be developed, along with modulators of other phosphatases like INPP4B, which has recently begun receiving attention as an attenuator of cell signaling.84,153,154 As these small molecules become more developed, advancement to the clinic is inevitable, with the SHIP1 agonist AQX-1125 leading the way. This field appears primed to significantly advance in the next decade, with validation of these enzymes as targets for cancer, diabetes and bone marrow transplantation to join treatments already underway for inflammation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (RO1 HL72523, R01 HL085580, R01 HL107127) and the Paige Arnold Butterfly Run. WGK is the Murphy Family Professor of Children's Oncology Research, an Empire Scholar of the State University of NY and a Senior Scholar of the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America.

Biography

Dennis R. Viernes received his B.S. degree in Chemistry from De La Salle University–Manila in the Philippines in 2003. After spending some years in academia as a part–time lecturer, he moved to the United States to pursue graduate studies. He earned his Ph.D. in Chemistry from Syracuse University in 2012 where he worked on the synthesis of SHIP modulators and synthetic studies on some natural products. He is currently working as a postdoctoral research associate on the synthesis of chiral sultines and investigating their role in asymmetric induction of helicity.

Lydia B. Choi received her B.S. degree in Biochemistry from Syracuse University in 2006. After spending a year in industry, she returned to Syracuse University and earned an MS with thesis in Chemistry in 2011. She then enrolled in Fordham University where she is completing her J.D. requirements. She is currently working as an intellectual property summer associate at the law firm of Foley and Lardner, LLP in its ChemBio Practice Group.

William G. Kerr received his B.S. degree in Chemistry from Lehigh in 1982 with a minor in Molecular Biophysics. He completed his Ph.D. in Cell and Molecular Biology the University of Alabama at Birmingham in 1987. He spent the next 6 years in the Genetics Dept. at Stanford University where he developed enhancer and gene-trap approaches to clones differentially expressed genes. SHIP1 was among the genes he trapped. After a brief stint at the first company devoted to stem cells and their application to treatment of disease (SyStemix, Inc.) he returned to academia as an Assistant Professor at the University of Pennsylvania in 1996. There he identified a stem cell specific SHIP1 isoform, s-SHIP, and developed the first mouse model with a SHIP floxed allele that has enabled his lab and others worldwide to study SHIP1 function in vivo using a conditional mutation strategy. In 2010 Dr. Kerr's lab reported the first small molecular inhibitors of SHIP1 and has utility of SHIP inhibitors in cancer, blood cell recovery and suppression of allogeneic T cell responses. Dr. Kerr is formerly the Newman Family Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society and is currently the Murphy Family Professor of Children's Oncology Research AT SUNY Upstate Medical University, and Empire Scholar and was recently named a Senior Scholar of the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America for his research showing that mutation of SHIP1 causes Crohn's Disease in mice.

John D. Chisholm received his B.S. degree in Chemistry from Alma College in 1992. After spending two years at the Upjohn Company as an associate chemist, he returned to graduate school and earned a Ph.D. in Organic Chemistry from the University of California, Irvine in 2000. He received his postdoctoral training from Stanford University in organic and organometallic chemistry before joining the faculty at Syracuse University, where he is currently an associate professor of chemistry and a member of the Upstate Cancer Research Institute. His current research interests include the medicinal chemistry of SHIP modulators as well as the development of new synthetic methods for carbon-carbon bond formation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ooms LM, Horan KA, Rahman P, Seaton G, Gurung R, Kethesparan DS, Mitchell CA. The role of the inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatases in cellular function and human disease. Biochem J. 2009;419:29–49. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyson JM, Fedele CG, Davies EM, Becanovic J, Mitchell CA. Phosphoinositide phosphatases: just as important as the kinases. Subcell Biochem. 2012;58:215–279. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-3012-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bunney TD, Katan M. Phosphoinositide signalling in cancer: beyond PI3K and PTEN. NatRevCancer. 2010;10:342–352. doi: 10.1038/nrc2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edimo WsE, Janssens V, Waelkens E, Erneux C. Reversible Ser/Thr SHIP phosphorylation: A new paradigm in phosphoinositide signalling? Targeting of SHIP1/2 phosphatases may be controlled by phosphorylation on Ser and Thr residues. BioEssays. 2012;34:634–642. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu P, Cheng H, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:627–644. doi: 10.1038/nrd2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster JG, Blunt MD, Carter E, Ward SG. Inhibition of PI3K signaling spurs new therapeutic opportunities in inflammatory/autoimmune diseases and hematological malignancies. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:1027–1054. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.004051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blunt MD, Ward SG. Pharmacological targeting of phosphoinositide lipid kinases and phosphatases in the immune system: success, disappointment, and new opportunities. Front Immunol. 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00226. Article 226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suwa A, Kurama T, Shimokawa T. SHIP2 and its involvement in various diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:727–737. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2010.492780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton MJ, Ho VW, Kuroda E, Ruschmann J, Antignano F, Lam V, Krystal G. Role of SHIP in cancer. Exp Hematol. 2011;39:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandes S, Iyer S, Kerr WG. Role of SHIP1 in cancer and mucosal inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1280:6–10. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerr WG. Inhibitor and Activator: Dual Functions for SHIP in Immunity and Cancer. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2011;1217:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyer S, Margulies BS, Kerr WG. Role of SHIP1 in bone biology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1280:11–14. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X, Majerus PW. Phosphatidylinositol signaling reactions. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:153–160. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1997.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catimel B, Yin M-X, Schieber C, Condron M, Patsiouras H, Catimel J, Robinson DEJE, Wong LS-M, Nice EC, Holmes AB, Burgess AW. PI(3,4,5)P3 Interactome. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:3712–3726. doi: 10.1021/pr900320a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide-3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marion F, Williams DE, Patrick BO, Hollander I, Mallon R, Kim SC, Roll DM, Feldberg L, Van Soest R, Andersen RJ. Liphagal, a Selective Inhibitor of PI3 Kinase a Isolated from the Sponge Aka coralliphaga: Structure Elucidation and Biomimetic Synthesis. Org Lett. 2006;8:321–324. doi: 10.1021/ol052744t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, He J, Kutateladze TG, Sakai T, Sasaki T, Markadieu N, Erneux C, Prestwich GD. 5–Stabilized Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5–Trisphosphate Analogues Bind Grp1 PH, Inhibit Phosphoinositide Phosphatases, and Block Neutrophil Migration. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:388–395. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leslie NR, Biondi RM, Alessi DR. Phosphoinositide-regulated kinases and phosphoinositide phosphatases. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2365–2380. doi: 10.1021/cr000091i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krystal G. Lipid phosphatases in the immune system. Semin Immunol. 2000;12:397–403. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sewell GW, Marks DJ, Segal AW. The immunopathogenesis of Crohn's disease: a three-stage model. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:506–513. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veillette A, Latour S, Davidson D. Negative regulation of immunoreceptor signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:669–707. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.081501.130710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor V, Wong M, Brandts C, Reilly L, Dean NM, Cowsert LM, Moodie S, Stokoe D. 5’ phospholipid phosphatase SHIP-2 causes protein kinase B inactivation and cell cycle arrest in glioblastoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6860–6871. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6860-6871.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerr WG. A role for SHIP in stem cell biology and transplantation. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2008;3:99–106. doi: 10.2174/157488808784223050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franke TF, Kaplan DR, Cantley LC, Toker A. Direct regulation of the Akt proto-oncogene product by phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate. Science. 1997;275:665–668. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma K, Cheung SM, Marshall AJ, Duronio V. PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 levels correlate with PKB/akt phosphorylation at Thr308 and Ser473, respectively; PI(3,4)P2 levels determine PKB activity. Cell Signal. 2008;20:684–694. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks R, Fuhler GM, Iyer S, Smith MJ, Park MY, Paraiso KH, Engelman RW, Kerr WG. SHIP1 Inhibition Increases Immunoregulatory Capacity and Triggers Apoptosis of Hematopoietic Cancer Cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3582–3589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]