Abstract

This paper demonstrates that low-skilled Mexican-born immigrants’ location choices in the U.S. respond strongly to changes in local labor demand, and that this geographic elasticity helps equalize spatial differences in labor market outcomes for low-skilled native workers, who are much less responsive. We leverage the substantial geographic variation in employment losses that occurred during Great Recession, and our results confirm the standard finding that high-skilled populations are quite geographically responsive to employment opportunities while low-skilled populations are much less so. However, low-skilled immigrants, especially those from Mexico, respond even more strongly than high-skilled native-born workers. Moreover, we show that natives living in metro areas with a substantial Mexican-born population are insulated from the effects of local labor demand shocks compared to those in places with few Mexicans. The reallocation of the Mexican-born workforce reduced the incidence of local demand shocks on low-skilled natives’ employment outcomes by more than 50 percent.

1 Introduction

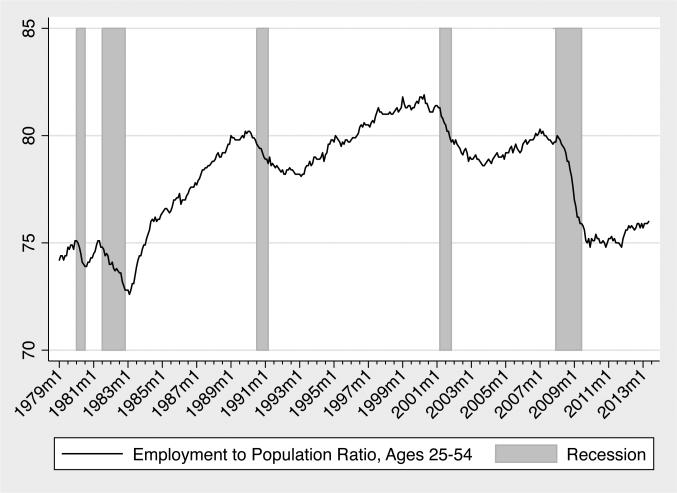

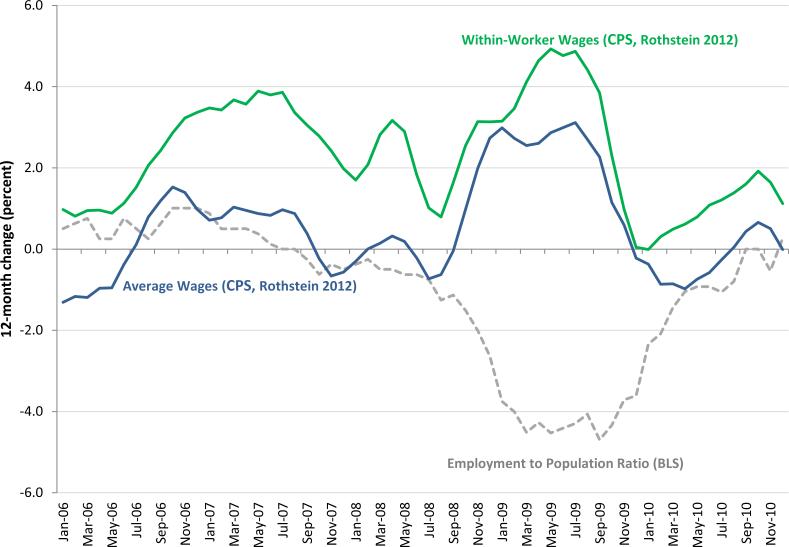

Over the past two decades, the labor market in the United States has shown signs of becoming less dynamic in a number of important ways. Job creation, job destruction, and job-to-job transitions have all fallen markedly (Davis, Faberman and Haltiwanger 2012, Hyatt and Spletzer 2013). Additionally, fewer people are making long-distance moves (Molloy, Smith and Wozniak 2011), which is concerning because geographic labor mobility is a primary means of equilibrating differences across local labor markets (Blanchard and Katz 1992). This declining dynamism is of particular concern for low-skilled workers during periods like the Great Recession, which featured mass unemployment and sharp differences across local markets. Not only are less educated workers disproportionately affected by job losses during downturns (Hoynes 2002, Hoynes, Miller and Schaller 2012), but a prominent literature finds that they are the least likely to move from depressed areas toward markets with better earnings prospects (Topel 1986, Bound and Holzer 2000, Wozniak 2010). The substantial geographic variation in labor market conditions during the Great Recession, combined with low levels of geographic mobility, created the potential for sharply disparate labor market outcomes across space, especially among workers without a college education.

In this paper, we examine mobility responses to geographic variation in the depth of the Great Recession, with the goal of determining how such mobility affects the incidence of local demand changes. The analysis reveals an important and novel finding: in sharp contrast to their native-born counterparts, low-skilled Mexican-born workers were quite likely to make earnings-sensitive location choices, and this population shifted markedly away from the hardest hit metro areas toward more favorable markets.1 Importantly, this mobility occurred not only among new arrivals, but also among immigrants who were living in the US prior to the recession. Moreover, demand-sensitive migration by Mexican-born immigrants dramatically reduced the geographic variability of labor market outcomes faced by less-skilled natives. Natives in metro areas with a substantial Mexican-born population experienced a more than 50 percent weaker relationship between local demand shocks and local employment rates, compared to metro areas with relatively small Mexican-born populations.

Conducting this type of analysis requires identifiable changes in labor demand. During the Great Recession, as in previous downturns, the primary employer response to declining product demand was to cut employment rather than to reduce wages. This feature makes it possible to determine which metro areas faced larger and smaller demand shocks by observing relative changes in employment across those locations. We also instrument for local labor demand using the standard Bartik (1991) measure that relies on the pre-Recession industrial composition of local employment. The results confirm the previous literature's finding of a strong education gradient in geographic responsiveness to labor market conditions. For example, among highly skilled (some college or more) native men, a 10 percentage point larger decline in local employment from 2006 to 2010 led to a 4.6 percentage point relative decline in the local population, compared with no measurable supply response among less skilled (high school degree or less) natives. In sharp contrast, less skilled Mexican-born men responded even more strongly than highly skilled natives, with a 10 percentage point larger employment decline driving a 5.7 percentage point larger decline in population. Immigrants thus play a crucial and understudied role in increasing the overall geographic responsiveness of less skilled laborers in the U.S., and this result adds a new dimension to the existing literature that focuses on workers’ responsiveness to demand shocks based on education and demographics.2

Having established that less skilled Mexicans are highly geographically responsive to changes in labor market conditions while less skilled natives are not, we examine the implications of Mexican mobility for natives’ employment outcomes. We find that in metro areas where the Mexican-born comprised a substantial share of the low-skilled workforce prior to the recession, there was a much weaker relationship between labor demand shocks and native employment probabilities than in areas with relatively few Mexican workers. Natives living in metro areas with many similarly skilled Mexicans were thus insulated from local shocks, as the departure (arrival) of Mexican workers absorbed part of the relative demand decline (increase). Therefore, Mexican mobility serves to equalize labor market outcomes across the country, even among the less mobile native population.

Finally, we consider possible explanations for why the Mexican-born are more likely to make demand-sensitive long-distance moves. We begin by noting that a portion of the difference can be explained by larger overall mobility rates when including international migration. The remainder reflects differential sensitivity to changing labor market conditions, and we thus examine a number of reasons why the location decisions of the Mexican-born are more responsive. We consider differences in observable demographic characteristics such as age, education, family structure, and home ownership, but find that these do not account for the differential responsiveness. Instead, we conclude that a likely contributing factor is the fact that the Mexican-born are a self-selected group of people with high levels of labor force attachment and a greater willingness to move long distances to encounter more favorable labor market conditions. In addition, Mexican-born workers have access to a particularly robust network that reduces both the costs of acquiring information about distant labor markets and the financial costs of moving (Munshi 2003).

These findings have important implications for multiple literatures. First, as mentioned above, various papers find that the mobility of workers reduces geographic inequality (Bartik 1991, Blanchard and Katz 1992) and that differences in responsiveness across worker types determine the degree to which local shocks are realized in local outcomes for particular worker groups (Topel 1986, Bound and Holzer 2000). Prior work has focused on differences across education groups, and we confirm that native-born less skilled workers respond much less strongly to local market conditions than their higher skilled counterparts do. We further demonstrate an even larger difference in responsiveness within the less skilled market, between immigrants and natives. This distinction between less skilled immigrants and natives likely explains why we find an important role for equalizing migration, while other recent work focusing on citizens (Yagan 2014) or total population (Mian and Sufi 2014) finds a more limited role for migration during the Great Recession. We show that the presence of highly responsive immigrants increases the overall geographic elasticity of the less skilled labor force, and immigrants’ mobility serves as a form of labor market insurance by transferring employment probability from relatively strong markets to relatively weak ones. Importantly, immigrants’ mobility mitigates the very negative outcomes that natives otherwise would have faced in the most depressed local markets, which had been the primary concern of the earlier literature.

Second, demand-driven location choices by immigrants represent a central challenge in the literature measuring immigrants’ effects on natives’ labor market outcomes. To address this challenge, researchers have used instrumental variables based on the existing locations of immigrant enclaves (Card (2001), for example) or relied on national time-series identification rather than cross-geography comparisons (Borjas 2003).3 Our results confirm the hypothesis that immigrants’ location choices respond strongly to local economic conditions, and we show that during the Great Recession more than 75 percent of Mexican immigrants’ geographic response occurred through return migration or internal migration by previous immigrants, channels that are largely neglected in prior work.4 This finding demonstrates that geographic arbitrage can occur even without much new immigration, as long as the labor market has a large stock of immigrants whose location choices are highly sensitive to employment opportunities. Moreover, the fact that immigrants’ mobility reduces variability in labor market outcomes faced by natives is an important effect of immigration on the host country, and a complete welfare accounting should take it into consideration.5

Third, the most closely related prior work is Borjas's (2001) seminal paper, which introduced the possibility of spatial arbitrage through the arrival of new immigrants to states with high wage levels and simulated the potential geographic smoothing effect on natives’ wages. Although similar in examining geographic smoothing resulting from immigrants’ location choices, the current paper differs in important ways. Our unit of analysis is the metropolitan area rather than the state, allowing us to more closely approximate local labor markets. Importantly, we focus on responses to plausibly exogenous labor demand shocks rather than to unconditional wage levels or wage growth. As just mentioned, we examine the importance of return migration and internal migration rather than focusing only on newly arrived immigrants. Finally, we introduce a test to demonstrate empirically the geographic smoothing that Borjas investigated through simulation. Rather than assuming a particular degree of substitutability between immigrants and natives, we uncover a relationship in the data that would not exist if immigrants and natives did not compete for similar jobs. In this sense, our work provides strong empirical support for his hypothesis that immigration “greases the wheels of the labor market,” while expanding the finding to show that immigrants continue to fulfill this role even after arrival.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: the next section provides context for examining demand-sensitive location choices during the Great Recession. Section 3 provides the main results and multiple robustness checks of the Mexican/native-born differences in geographic responsiveness. Section 4 demonstrates that Mexican immigrants’ mobility smooths labor market outcomes for natives. Section 5 shows that similar mobility and smoothing results apply during the pre-Recession period. Section 6 decomposes the supply responses into various channels and discusses potential reasons why Mexican-born immigrants may be uniquely positioned to serve as an equilibrating force in the low-skilled labor market. Section 7 concludes.

2 Background and Conceptual Framework

2.1 Measuring Demand Shocks

Like many previous recessions, the Great Recession was characterized by large employment declines and much smaller wage cuts.6 Our initial identification strategy exploits the fact that employers adjusted primarily on the employment margin rather than the wage margin, which makes it possible to observe the relative size of demand declines across metro areas directly through employment changes. Note that for our purposes, it is unimportant why employers responded this way; rather, this approach simply requires the descriptive fact that the bulk of the response occurred through employment.7 We therefore initially measure each metro area's demand shock as the proportional decline in observed payroll employment, and then examine how local labor supply responded to this measure of the degree to which local conditions deteriorated. It is important to emphasize that this approach is appropriate only because of the particular features of the labor market during the Great Recession and would likely not be applicable in periods with low rates of unemployment, when employment changes are more likely to reflect shifts in both supply and demand.

Although the recessionary environment makes it plausible that changes in employment reflect only changes in demand, changes in the size of the local population may affect local labor demand through the consumer demand channel, creating a reverse causality problem. As we discuss in more detail in section 3.2, it is unlikely that the resulting bias will vary substantially across demographic groups, implying that the relative supply responses across groups remain informative. However, we further support this interpretation by conducting IV analysis using the Bartik (1991) measure as an instrument for changes in local employment. These results are very similar to those using OLS, and in most specifications, we fail to reject the null hypothesis that the two sets of estimates are equal, which supports the interpretation that measured employment changes reflect demand shocks.

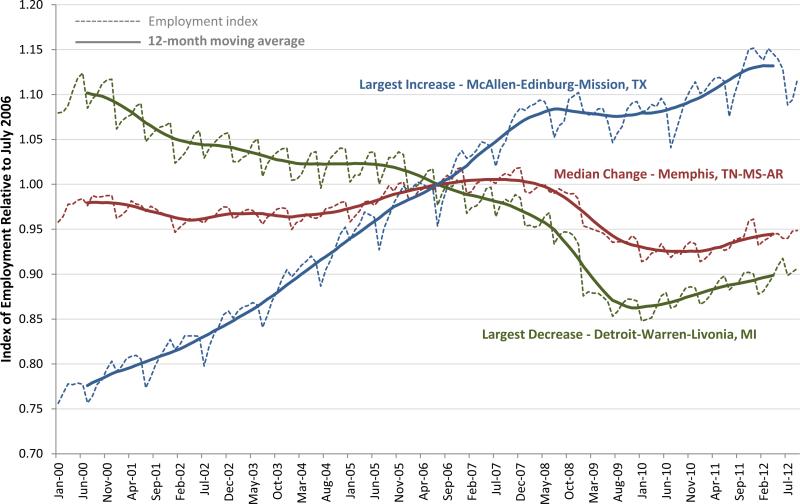

2.2 Geographic Variation in Employment Changes

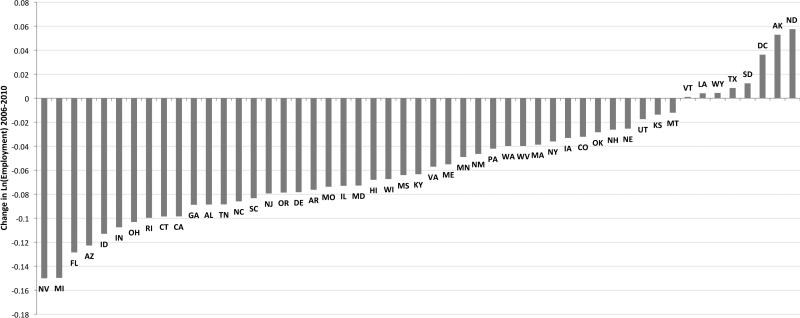

There was considerable geographic variation in the depth of the recession. The hardest-hit locations (e.g. Nevada, Michigan, Florida) lost more than ten percent of employment from 2006-2010, while a few places (including North and South Dakota and Texas) experienced modest employment growth over the same period.8 Our empirical specifications define a local labor market as a metropolitan area (we will use the word “city” interchangeably for ease of exposition), and there was even greater variation in employment changes at this level of geography.9

Several recent papers examine the sources of these differences. Mian and Sufi (2014) show that counties with higher average household debt-to-income ratios in 2006 experienced larger declines in household expenditure and hence larger employment declines, particularly in non-traded industries that depend on local consumer demand. Greenstone, Mas and Nguyen (2014) show that counties whose small businesses borrowed primarily from banks that cut lending following the financial crisis experienced larger employment declines, and Chodorow-Reich (2014) provides direct evidence that firms with greater exposure to such banks experienced greater employment losses. Fort, Haltiwanger, Jarmin and Miranda (2013) show that states facing larger housing price declines experienced declining employment among young small businesses who often rely on home equity financing. Further, certain industries (notably construction and manufacturing) experienced especially large losses in employment, and these industries comprised different shares of local demand for labor. We leverage the resulting geographic variation in the local depth of the recession to identify the effects of labor market strength on individuals’ location choices.

2.3 Geographic Mobility 2006-2010

Throughout our analysis, we consider locational supply responses separately by sex, skill, and nativity.10 Table 1 reports long-distance (cross-city or international) mobility rates for these demographic groups. Immigration and internal migration are measured using the ACS, while emigration to Mexico is measured in the 2010 Mexican Decennial Census. In all cases, the numbers reflect average annual mobility rates throughout our study period.11 Notably, every demographic and skill group experienced substantial mobility over this time period, which suggests that there is scope for the reallocation of labor across markets in response to local shocks. In nearly all cases the more educated portion of each demographic group exhibits a higher mobility rate. Natives are generally more likely to have moved within the U.S., while the foreign-born are more likely to have moved from an international location.12 As expected, emigration to Mexico is an important channel for Mexican-born population adjustment during this time period.13 Overall, less skilled Mexican-born individuals are substantially more likely to have moved during our sample period than are similarly skilled natives. For example, less skilled Mexican men's yearly migration rate was 7.0 percent, while the same rate for natives was 4.0 percent.

Table 1.

Average Yearly Mobility Rates

| Native-Born | Foreign-Born | Mexican-Born | Other Foreign-Born | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Men, High-school or less | ||||

| Immigration | 0.2% | 1.9% | 1.8% | 2.1% |

| Internal Migration | 3.8% | 3.3% | 3.0% | 3.6% |

| Emigration to Mexico | 1.2% | 2.3% | ||

| Total | 4.0% | 6.4% | 7.0% | 5.7% |

| Panel B: Men, Some college or more | ||||

| Immigration | 0.3% | 2.8% | 1.9% | 2.9% |

| Internal Migration | 4.6% | 4.7% | 3.3% | 4.9% |

| Emigration to Mexico | 0.1% | 1.0% | ||

| Total | 4.8% | 7.7% | 6.2% | 7.8% |

| Panel C: Women, High-school or less | ||||

| Immigration | 0.1% | 1.8% | 1.2% | 2.4% |

| Internal Migration | 3.6% | 2.9% | 2.4% | 3.2% |

| Emigration to Mexico | 0.4% | 1.0% | ||

| Total | 3.7% | 5.1% | 4.5% | 5.6% |

| Panel D: Women, Some college or more | ||||

| Immigration | 0.2% | 2.8% | 1.7% | 2.9% |

| Internal Migration | 4.4% | 4.3% | 3.1% | 4.4% |

| Emigration to Mexico | 0.1% | 0.8% | ||

| Total | 4.5% | 7.2% | 5.6% | 7.3% |

Sample: individuals aged 18-64, not enrolled in school, and not in group quarters at the time of the survey. “Immigration” and “Internal Migration” are calculated using the 1-year mobility question in the 2006-2010 ACS. “Immigration” reports (individuals arriving in MSAs from abroad) / (individuals living in an MSA in the survey year or prior year). “Internal Migration” reports (individuals moving across MSA boundaries within the U.S. who arrived in or left an MSA) / (individuals living in an MSA in the survey year or prior year). These are calculated for each ACS year and averaged across years. “Emigration to Mexico” is calculated using the 2010 Mexican Census and the 2005 ACS, and reports (individuals moving from the U.S. to Mexico between June 2005 and June 2010) / (individuals living in the U.S. in 2005), divided by 5 for the average yearly rate. The values are approximately zero for all but the Mexican-born.

We stratify our analysis by nativity not only because immigrants are more mobile in general, but also because they are likely more motivated by labor market conditions when selecting a location. In section 6.2, we discuss multiple pieces evidence that the Mexican-born are especially likely to move for economic rather than personal reasons. Thus, the differences across groups in supply responses that we document below reflect both differences in the unconditional probability of moving and differences in responsiveness to economic conditions among those who migrate.

3 Population Responses to Demand Shocks

3.1 Data Sources and Specifications

Our empirical strategy examines changes in a city's working age population (separately by sex, skill level, and nativity) as a function of the relevant demand shock, as reflected by changes in payroll employment. Our dependent variable is the change in the natural log of the relevant demographic group's population from 2006-2010, calculated from the American Community Survey (ACS).14 Note that the ACS sample includes both authorized and unauthorized immigrants.15 Our sample includes individuals ages 18-64, not currently enrolled in school, and not living in group quarters. Because we will examine tightly defined groups of workers, we limit our analysis to cities with a population of at least 100,000 adults meeting these sampling criteria. Additionally, we drop cities with fewer than 60 sampled Mexican-born individuals in 2006 and cities with any empty sample population cells (for any demographic group) in the 2006 or 2010 ACS. These city-level restrictions are imposed uniformly, resulting in a sample of 95 cities in each regression.16

Although we do not estimate a formal location choice model, both Borjas (2001) and Cadena (2013) provide theoretical (discrete-choice-based) justifications for using linear models to examine proportional changes in supply as a function of changes in expected earnings.17 Note that with only small changes in wages, the percentage change in expected earnings that a labor market offers (prior to any mobility) will be approximately equal to the percentage change in the number of jobs. We therefore use changes in the natural log of employment as our primary measure of local demand shocks, which we calculate using employment information from County Business Patterns (CBP) data.18 Throughout the discussion we use the notation ẋ to signify changes in logs: ẋ ≡ log(x1)–log(x0). Unless otherwise noted, this change refers to the 2006 to 2010 long difference. Our primary specification is thus

| (1) |

where c indexes metro areas, Ṅc is the proportional change in working-age population, and L̇c is the proportional change in employment from 2006-2010.

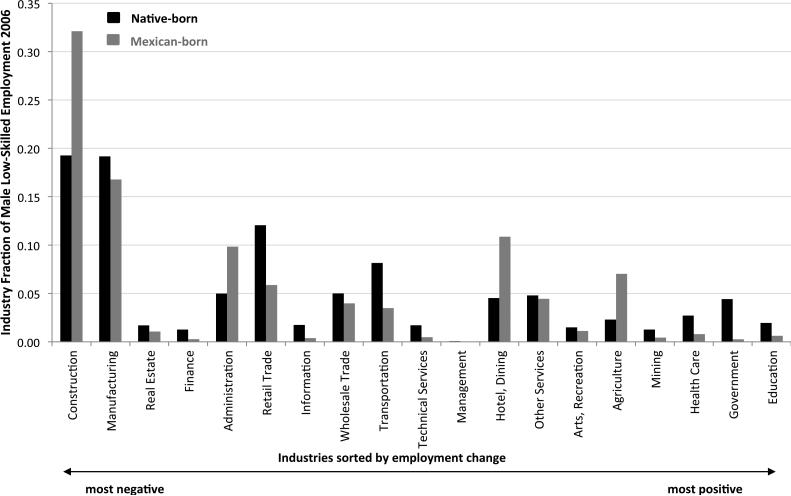

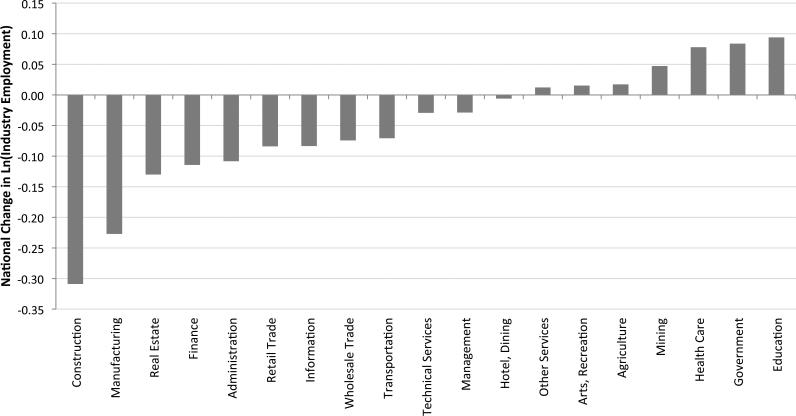

One concern with this basic specification is that overall employment changes understate the change in expected earnings for low-skilled and foreign-born workers, who were disproportionately represented in the hardest-hit industries.19 There was considerable variation in employment declines across industries, and Mexican-born workers (the largest single group among the low-skilled foreign-born) were more concentrated in the types of jobs that experienced the largest declines (see Appendix section A.2 for details). We therefore construct group-specific employment changes that account for these differing industrial compositions.20 Note that the proportional change in city c's overall employment can be expressed as a weighted average of industry-specific (i) employment changes, with weights equal to the industry's share of total employment in the initial period.

| (2) |

Based on this insight, we calculate the relevant change in employment for a given education and/or demographic group, g, using industry employment shares that are specific to each group, , rather than shares for the local economy as a whole, such that .21

The primary advantage of the CBP is that it obtains data from the universe of establishments in covered industries. Unfortunately, the CBP data do not cover employment in agricultural production, private household services, or the government. In our preferred specifications, therefore, we fill in the missing changes in employment using (city x industry) calculations from the ACS.22 The only remaining concern, therefore, is the informal sector. If the employment losses in the informal sector are similar (in proportional terms) to losses in the formal sector, the results will be unaffected. It is nevertheless possible that foreign-born workers face larger employment declinesthan our measure indicates. Given the substantial difference in the responsiveness of native and foreign-born individuals, however, this issue seems unlikely to drive the results.

Our preferred specification also weights each city to account for the heteroskedasticity inherent in measuring proportional population changes across labor markets of various sizes. We construct efficient weights based on the sampling distribution of population counts, accounting for individuals’ ACS sampling weights.23 In practice, nearly all of the cross-city variation in the optimal weights derives from differences in the 2006 population, and results from population-weighted specifications are quite similar. Additionally, unweighted specifications produce qualitatively similar results in most specifications, particularly for the native-born and Mexican-born low-skilled workers that we focus on.24

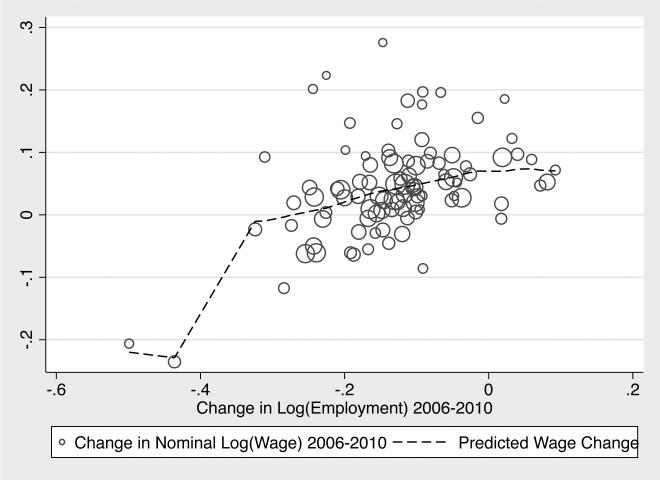

Finally, we note that although employment changes represent the bulk of employers’ responses to demand changes, there is a small positive correlation between wage changes and employment changes across metro areas.25 Thus the elasticity of population with respect to payroll employment slightly overstates the supply elasticity with respect to expected earnings. However, our primary interest is the difference in elasticities across demographic groups rather than the level of the effect per se, and we do not expect wages to adjust differently across nativity groups. In fact, we have examined the time series of wages separately for native-born and Mexican-born workers, and we find no appreciable difference in the degree to which wages adjusted rather than employment.

3.2 Geographic Labor Supply Elasticities by Demographic Group

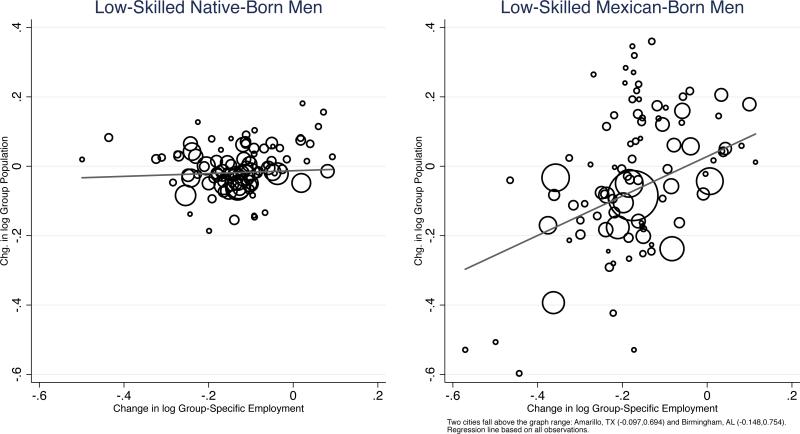

Figure 1 shows scatter plots based on equation (1) for low-skilled native-born and Mexican-born men. Each circle represents a metro area, with its size proportional to the weight it receives in the regression.26 The x-axis shows the change in log employment, constructed using industry shares specific to each worker type, and the y-axis shows the change in log population for the relevant group.27 The figure clearly demonstrates our central finding regarding the labor supply responses of less-skilled workers: Mexican-born workers respond much more strongly to local labor demand shocks than do natives, with Mexican-born population shifting away from the hardest-hit cities and toward those with relatively mild downturns, while native populations respond much less.

Figure 1.

Population Responses to Employment Shocks: Native-born and Mexican-born Low-Skilled Men

Source: Authors’ calculations from American Community Survey and County Business Patterns. Changes calculated as the long difference in logs from 2006 to 2010. Individual sample, 95 city sample, and construction of group-specific employment changes described in the text. Weighted to account for heteroskedasticity (details in appendix).

Table 2 reports similar elasticities for a variety of groups defined by skill, sex, and nativity, with each coefficient in the table coming from a separate regression. For example, the Native-born and Mexican-born coefficients for less skilled men in Panel A correspond to the scatter plots in Figure 1. Comparing Panels A and C to B and D, respectively, we find the well-established empirical regularity that, in general, workers with at least some college education are much more responsive than are workers with at most a high school degree. There are also substantial differences among skill groups by nativity, with the foreign-born consistently more responsive than the native-born. For less skilled workers, the strongest mobility responses appear among Mexican-born immigrants, in sharp contrast to the very small and statistically insignificant estimates for natives.28 The fact that less-skilled Mexican-born immigrants respond so strongly to labor demand shocks is, to our knowledge, a novel finding. We therefore spend the remainder of the paper examining this result and its economic implications.

Table 2.

Population Response to Labor Demand Shocks

| Dependent Variable: Change in log of Population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Native-Born | Foreign-Born | Mexican-Born | Other Foreign-Born | |

| Panel A: Men, High-school or less | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.163*** (0.061) | 0.041 (0.072) | 0.388** (0.169) | 0.569*** (0.202) | −0.087 (0.264) |

| Panel B: Men, Some college or more | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.498*** (0.090) | 0.463*** (0.092) | 0.605*** (0.206) | 0.171 (0.316) | 0.717*** (0.209) |

| Panel C: Women, High-school or less | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.408*** (0.115) | 0.196 (0.156) | 0.616*** (0.186) | 0.652*** (0.192) | 0.505 (0.332) |

| Panel D: Women, Some college or more | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.475*** (0.126) | 0.440*** (0.118) | 0.826*** (0.271) | 0.218 (0.505) | 0.898*** (0.268) |

Each listed coefficient represents a separate regression of the change in log(population) for the relevant group (from the American Community Survey) from 2006-2010 on the change in log(group-specific employment) from County Business Patterns data over the same time period, using the demographic group's industry mix. All regressions include an intercept term and 95 city observations. Observations are weighted by the inverse of the estimated sampling variance of the dependent variable (see appendix for details). Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors in parentheses

significant at the 1% level

5%

* 10%.

To rule out the possibility that the Mexican mobility result is driven by changes in other determinants of location choice that may be correlated with local changes in demand, we introduce a variety of controls. We control for the Mexican-born share of each city's population in 2000, which accounts for the potential decline in the value of traditional enclaves discussed by Card and Lewis (2007). We also add indicators for cities in states that enacted anti-immigrant employment legislation or new 287(g) agreements allowing local officials to enforce federal immigration law, based on the immigration policy database in Bohn and Santillano (2012). Table 3 presents population elasticities analogous to Table 2, with the addition of these controls.29 The pattern of elasticities remains essentially unchanged.30

Table 3.

Population Response to Labor Demand Shocks - With Enclave and Policy Controls

| All | Native-Born | Foreign-Born | Mexican-Born | Other Foreign-Born | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Men, High-school or less | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.150** (0.063) | 0.040 (0.071) | 0.292** (0.141) | 0.475*** (0.172) | −0.084 (0.281) |

| Panel B: Men, Some college or more | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.479*** (0.074) | 0.435*** (0.082) | 0.631*** (0.187) | 0.014 (0.285) | 0.742*** (0.204) |

| Panel C: Women, High-school or less | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.395*** (0.121) | 0.166 (0.157) | 0.631*** (0.179) | 0.743*** (0.202) | 0.444 (0.348) |

| Panel D: Women, Some college or more | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.473*** (0.095) | 0.423*** (0.102) | 0.841*** (0.243) | 0.315 (0.597) | 0.939*** (0.248) |

Each listed coefficient represents a separate regression of the change in log(population) for the relevant group (2006-2010, using the American Community Survey) on the change in log(group-specific employment) from County Business Patterns data over the same time period, using the demographic group's industry mix. These specifications include the enclave and policy controls in Column (4) of Table A-1. All regressions include an intercept term and 95 city observations. Observations are weighted by the inverse of the estimated sampling variance of the dependent variable (see appendix for details). Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors in parentheses

significant at the 1% level

5%

* 10%.

Although the pattern of elasticities is robust to the controls just mentioned, there remains the possibility of reverse causality, in which unmeasured factors drive population changes, and these population changes result in changes in employment, either through decreasing consumer demand or by mechanically reducing the number of workers. We address this issue in two ways. First, we note that this mechanism would apply to all demographic and nativity groups. Thus, this alternative interpretation cannot explain the lack of a relationship between native population changes and employment changes, which exists despite substantial cross-city mobility (see Table 1). Moreover, since Mexicans often remit a substantial portion of their income rather than spending it locally, reverse causality through the demand channel would be stronger for natives and would bias the difference in elasticities in the opposite direction of the observed gap.

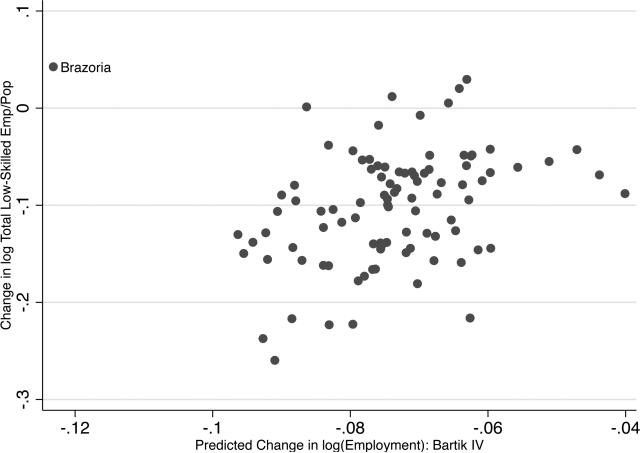

Second, we use the standard “Bartik instrument” (Bartik 1991), which predicts changes in local labor demand by assuming that national employment changes in each industry are allocated proportionately across cities, based on each city's initial industry composition of employment.31 This measure is plausibly exogenous to counterfactual population growth and strongly relates to changes in local employment. We calculate the instrument as , where is the fraction of city c employment in industry i in 2006, and L̇i is the proportional change in national employment in industry i.

The results when using ψc as an instrument for the local employment decline are presented in Table 4; these specifications also include the controls introduced in Table 3.32 For each specification, we report the IV elasticity estimates, the p-value of a test that the OLS and IV coefficients are equal, the first-stage coefficients on the instrument, and partial F Statistics for the instrument in the first stage.33 Although the instrument is identical in all cases, the first-stage coefficients differ based on how the Bartik measure relates to each group-specific employment decline. With the exception of highly skilled native women, we do not appear to face a weak instrument problem, and the first stage coefficients are similar in magnitude to those in the prior literature.34 The IV elasticity estimates for men are similar to the OLS results and exhibit an even larger difference in responsiveness between less skilled natives and Mexicans, though the estimates are less precise. In spite of a few negative point estimates for other immigrants and highly skilled workers, our conclusions regarding the strong responsiveness of less skilled Mexican immigrants and essentially no response among less skilled natives are supported when using this standard method of isolating demand shocks.35 The coefficient estimate of 0.922 for low-skilled Mexican-born men implies that a city facing a 10 percentage point larger employment decline experienced a 9.92 percentage point larger decline in Mexican-born population. Compare this strong response to the very precisely estimated zero coefficient for low-skilled native men.

Table 4.

Population Response to Labor Demand Shocks: Bartik (1991) IV Estimates

| Dependent Variable: Change in log Population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Native-Born | Foreign-Born | Mexican-Born | Other Foreign-Born | |

| Panel A: Men, High-school or less | |||||

| IV Estimate | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.223 (0.166) | 0.007 (0.090) | 0.402 (0.409) | 0.992** (0.468) | −0.675** (0.278) |

| P-value testing shock exogeneity | 0.541 | 0.764 | 0.606 | 0.029 | 0.072 |

| First Stage | |||||

| Predicted Change in log Employment | 4.196*** (0.702) | 4.038*** (0.672) | 4.590*** (0.912) | 5.108*** (1.478) | 4.717*** (0.699) |

| Partial F Statistic | 35.74 | 36.13 | 25.31 | 11.94 | 45.60 |

| Panel B: Men, Some college or more | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.270* (0.157) | 0.411** (0.192) | −0.237 (0.264) | −0.475 (0.387) | −0.161 (0.329) |

| P-value testing shock exogeneity | 0.316 | 0.935 | 0.017 | 0.331 | 0.081 |

| First Stage | |||||

| Predicted Change in log Employment | 2.651*** (0.542) | 2.662*** (0.569) | 2.985*** (0.486) | 5.337*** (0.947) | 2.727*** (0.449) |

| Partial F Statistic | 23.89 | 21.91 | 37.76 | 31.79 | 36.89 |

| Panel C: Women, High-school or less | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.145 (0.168) | −0.405 (0.287) | 0.273 (0.504) | 1.811*** (0.665) | −0.979* (0.556) |

| P-value testing shock exogeneity | 0.169 | 0.040 | 0.315 | 0.047 | 0.022 |

| First Stage | |||||

| Predicted Change in log Employment | 2.067*** (0.387) | 2.068*** (0.405) | 2.167*** (0.419) | 2.502*** (0.675) | 1.983*** (0.317) |

| Partial F Statistic | 28.59 | 26.09 | 26.76 | 13.73 | 39.17 |

| Panel D: Women, Some college or more | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | −0.066 (0.378) | −0.054 (0.420) | −0.754 (0.716) | 0.438 (0.919) | −1.092 (0.738) |

| P-value testing shock exogeneity | 0.209 | 0.368 | 0.010 | 0.886 | 0.056 |

| First Stage | |||||

| Predicted Change in log Employment | 1.081** (0.447) | 1.061** (0.449) | 1.580*** (0.439) | 2.915*** (0.558) | 1.364*** (0.377) |

| Partial F Statistic | 5.854 | 5.578 | 12.97 | 27.33 | 13.12 |

Each listed coefficient represents a separate instrumental variables regression of the change in log(population) for the relevant group (2006-2010, using the American Community Survey) on the change in log(group-specific employment) from County Business Patterns data over the same time period, using the demographic group's industry mix. All regressions include an intercept term, 94 city observations, and the enclave and policy controls in Column (4) of Table A-1. These specifications omit Brazoria, TX, which is a substantial outlier in the first stage; see appendix section A.9 for details. Observations are weighted by the inverse of the estimated sampling variance of the dependent variable (see appendix for details). Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors in parentheses

significant at the 1% level

5%

10%.

The excluded instrument is the predicted change in log(employment), based on Bartik (1991) and described in the text. The listed “p-value testing shock exogeneity” is from a test of the null hypothesis that the OLS and IV slope coefficients are equal to each other. The first-stage coefficient on the instrument and the partial F statistic are reported below the corresponding IV estimate.

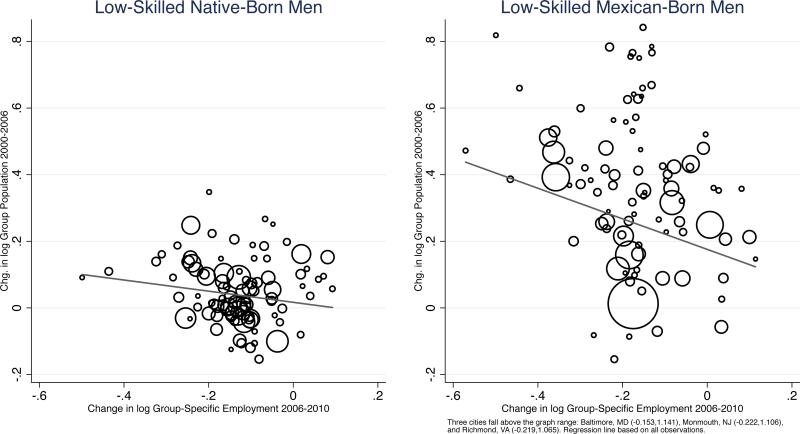

Finally, we use a false experiment approach to rule out the possibility that persistent unobserved factors drove the observed mobility responses. We regress pre-recession (2000-2006) population changes on the demand shocks from 2006-2010. Other than the change in the timing for the dependent variable, these specifications are identical to the main analysis. Figure 2 shows this falsification test for low-skilled Mexican-born and native-born men.36 For both groups, we find a negative relationship. Thus, if anything, the large population responses among the Mexican-born in the latter half of the decade represent a reversal of pre-recession trends. Note that cities facing larger employment declines during the Great Recession on average experienced larger employment increases during the pre-recession period, and additional analysis in section 5 directly supports the interpretation that population changes in the earlier period also reflect earnings-maximizing behavior.37

Figure 2.

Falsification Test: Population Change 2000-06 vs. Group-Specific Employment Change 2006-10

Source: Authors’ calculations from American Community Survey and County Business Patterns. Falsification test with changes in log(population) from 2000 to 2006 and changes in log(payroll employment) from 2006 to 2010. Individual sample, 95 city sample, and construction of group-specific employment changes described in the text. Weighted to account for heteroskedasticity (details in appendix).

Overall, this section documents sharp differences in the responsiveness of less skilled natives and Mexican immigrants to local labor demand shocks. This finding is robust to controlling for other determinants of immigrants’ location choices and to alternative approaches for identifying local labor demand shocks, and it was not driven by pre-existing migration patterns.38

4 Mexican Mobility Smooths Employment Outcomes

The previous section provides robust evidence that Mexican-born workers leave labor markets ex periencing larger labor demand declines in favor of markets facing smaller declines. Here we show that natives living in cities with substantial Mexican populations are insulated from the employment effects of local labor demand shocks.

4.1 Approach to Measuring Smoothing

We define smoothing as the degree to which workers’ employment probabilities are equalized across space rather than tied to local demand.39 Assuming that the employment probability is given by the ratio of employment to working-age population, Lc/Nc, one can measure the degree of smoothing based on the observed relationship between local changes in the employment rate (d ln(Lc/Nc)) and the local demand shock (d ln Lc). In the absence of any equalizing migration response, the local change in employment probability would be proportional to the labor demand decline in each city. In contrast, if earnings-sensitive migration was sufficient to equilibrate employment probabilities across cities, then the local change in employment probability would be uncorrelated with the local demand shock.

To formalize this intuition, consider the relationship between the local change in the employment rate and the local demand shock:

| (3) |

Labor demand shocks have a proportional direct effect on local changes in employment probability, but the observed effect may be mitigated by equalizing migration, reflected in a positive relationship between d ln Lc and d ln Nc. We therefore quantify smoothing by running the following regression:

| (4) |

The dependent variable is the change in the log of the employment to working-age population ratio calculated from ACS data.40 The independent variable is the change in the log of payroll employment, calculated from CBP data. Recall from Section 3.1 that we calculate proportional changes in city level payroll employment using a weighted average of proportional changes in city level industry employment. For this smoothing analysis, we initially use weights based on the pre-recession industry shares among all low-skilled workers in each city and calculate employment rates among the entire low skilled population.

A slope coefficient of one in this regression would imply that local employment changes depend entirely on local shocks, whereas a coefficient of zero would indicate that local outcomes are unrelated to local shocks, with only the aggregate national shock determining the realized change in employment rates. Because we only approximate the employment losses incident on low-skilled workers, however, we expect some attenuation of the estimated coefficient due to measurement error. We therefore focus on relative differences in coefficients across different cities rather than their absolute levels when evaluating the degree of smoothing.41

In particular, we measure the smoothing influence of Mexican mobility by dividing our sample of cities into those above and below the median Mexican-born share of the low-skilled population.42 Cities with few Mexican immigrants have little scope for outmigration in response to a larger-than-average demand decline. Further, when selecting a new location, Mexican movers (including new arrivals from abroad) tend to choose cities with higher Mexican-born populations, either because these populations themselves are a direct amenity or because they proxy for unobserved amenities especially valued by the Mexican-born. As a result, less-skilled workers’ employment probabilities in cities with many Mexicans should be less strongly related to local labor demand shocks than are those in cities with few Mexicans, which do not have access to equalizing Mexican mobility. We therefore estimate versions of (4) separately for cities with above- and below-median Mexican-born population shares, expecting to observe weaker relationships between employment probabilities and labor demand shocks in cities with many Mexican-born workers.

4.2 Smoothing Results

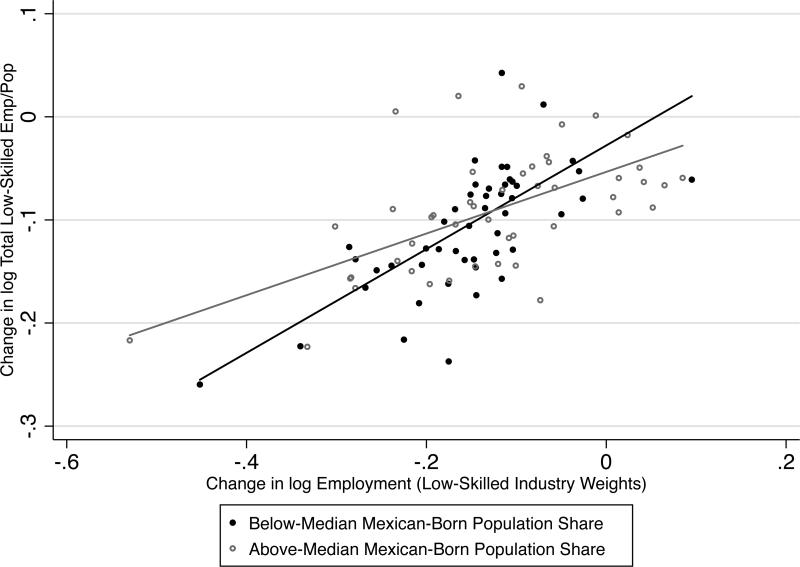

4.2.1 Smoothing in the Overall Less-Skilled Market

We first examine the smoothing effects of Mexican mobility for the low-skilled labor force as a whole. Figure 3 provides a visual representation of the results.43 As expected, there is a much weaker relationship between employment probabilities and demand shocks in cities with large Mexican populations than in cities with smaller Mexican populations.44 Table 5 panel (a) confirms this pattern using the Bartik (1991) instrument for local employment changes. In fact, the relationship is more than 50 percent weaker in cities with high concentrations of Mexican-born workers. By increasing the average mobility of the less-skilled population, Mexicans smooth average employment probabilities across space for less-skilled workers.

Figure 3.

Mexican Mobility Smooths Employment Outcomes: Change in Male Low-Skilled Emp/Pop Ratio vs. Change in Low-Skilled Employment

Source: Authors’ calculations from 2006-2010 American Community Survey and County Business Patterns. Changes in log(employment) and log(employment to population ratio) are calculated from 2006 to 2010 for low-skilled men (without regard to nativity). Construction of group-specific employment changes and weights described in the text and the appendix. Fitted lines are from a weighted regression using efficiency weights based on the entire low-skilled male population in each city. See Table A-31 for slope estimates.

Table 5.

Mexican Mobility Smooths Employment Outcomes: Bartik (1991) IV Estimates

|

dependent variable: change in log employment/population (ACS)

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City's Mexican population share |

|||

| below-median | above-median | difference | |

| (a) dependent variable sample: less-skilled men | |||

| change in log employment for less-skilled men (CBP) | 0.685*** (0.119) | 0.305*** (0.071) | −0.380*** (0.138) |

| (b) dependent variable sample: native less-skilled men | |||

| change in log employment for less-skilled men (CBP) | 0.731*** (0.138) | 0.283*** (0.072) | −0.448*** (0.155) |

| (c) dependent variable sample: native less-skilled men | |||

| change in log employment for less-skilled native men (CBP) | 0.736*** (0.131) | 0.305*** (0.077) | −0.431*** (0.152) |

| (d) dependent variable sample: native high-skilled men | |||

| change in log employment for high-skilled native men (CBP) | 0.293*** (0.112) | 0.214** (0.102) | −0.079 (0.151) |

Examines the relationship between labor market outcomes (changes in employment probability) and labor demand shocks (changes in payroll employment) separately for cities with above- and below-median Mexican population share to demonstrate the smoothing effect of Mexican mobility. Smaller coefficients indicate more smoothing. We use the predicted change in log(employment), based on Bartik (1991) and described in the text, as an instrument for the change in log(group-specific employment). Panel (a) examines the relationship between low-skilled employment shocks and low-skilled men's employment probability. Panel (b) examines the relationship between low-skilled employment shocks and low-skilled native men's employment probability. Panel (c) examines the relationship between low-skilled native employment shocks and low-skilled native men's employment. Panel (d) examines the relationship between high-skilled native employment shocks and high-skilled native men's employment. These specifications omit Brazoria, TX, which is a substantial outlier in the first stage; see appendix section A.9 for details.

This finding is a direct consequence of the mobility results in Section 3. Consider the following decomposition of the change in the less-skilled employment to population ratio (Lc/Nc) in a particular city.

| (5) |

where superscripts m and n refer to Mexicans and natives respectively, and ηc is the Mexican population share. Section 3 reveals that Mexican populations are more responsive to changes in demand than are native populations (), so cities with larger Mexican population shares exhibit a weaker (less positive) relationship between local shocks and local employment probabilities. Hence, the mobility results directly imply that Mexican mobility smooths average employment probabilities for the aggregate low-skilled workforce.

4.2.2 Smoothing in the Native Less-Skilled Market

The results presented thus far leave open the possibility that Mexican mobility equalizes overall less-skilled employment probabilities simply by equalizing employment rates among Mexicans without having any effect on the employment rates for less-mobile natives. We now determine whether native labor market outcomes are less related to local shocks in locations with larger Mexican population shares, by estimating versions of equation (4) in which the dependent variable is calculated using employment to population ratios for low-skilled native men (). Importantly, results using this approach are not mechanically driven by the preceding mobility results because changes in Mexican population do not appear in the denominator. Instead, Mexican mobility can affect the native employment to population ratio only by affecting native employment in the numerator.

Panel (b) of Table 5 shows the results. Changes in employment probabilities for natives living in cities with large Mexican populations are much less related to local demand conditions than are changes in cities with few Mexicans. The relationship in above-median cities is 61 percent weaker than in below-median cities. Thus, native employment probabilities were insulated from local shocks in the presence of substantial numbers of Mexican-born workers, with improved native outcomes in the hardest hit cities and diminished ones in more favorable markets.

To understand the scale of the smoothing result, consider a city that faced a relatively severe employment decline but that had few low skilled Mexican-born workers, such as Orlando, FL.45 Orlando experienced a decline in the native employment to population ratio from 78.6 to 66.0 percent from 2006 to 2010. If the labor market were characterized by full smoothing, with all cities experiencing the average decline in employment rates, Orlando's rate would have declined to only 73.6 percent in 2010. The smoothing estimates in panel (b) of Table 5 imply that if Orlando had a larger Mexican-born population comparable to that of Phoenix, AZ, which faced a similar employment shock, its native employment to population ratio would have fallen to 68.7, which is substantially closer to the full smoothing level than is 66.0.46 Thus, the employment to population ratio in Orlando was 2.7 percentage points lower than it might have been had a substantial Mexican-born population been present to absorb some of the local shock through equalizing migration. It is important to emphasize that the same smoothing results imply opposite effects for cities experiencing relatively positive shocks. In that case, cities with low Mexican-born populations experienced more positive employment growth than would have occurred in the presence of equalizing migration.

The findings in Panel (b) of Table 5 are precisely what one would expect if the presence of Mexicans in a local market weakened the effects of a decline in labor demand on natives’ employment probabilities. However, there are two potential alternative explanations that we consider. In both cases the evidence supports interpreting the differential slopes as resulting from larger Mexican population shares.

First, suppose that less skilled Mexican immigrants and natives worked in completely different types of jobs, i.e. that the labor market were perfectly segmented by nativity. In this case, a measure of the local decline in total low skilled employment would not necessarily capture the demand declines facing the native portion of the market. The weaker relationship between shocks and employment rates could derive, in part, from measuring the relevant decline in demand for native workers more accurately in cities with fewer Mexican-born workers.47 To address this possibility, in panel (c) of Table 5 we adjust the independent variable and calculate proportional job losses using the city-specific industry distribution of native less skilled workers rather than the industry distribution of all less skilled workers in the city as in panel (b). The gap between high and low Mexican share cities decreases only slightly; the shock-outcome relationship is still 59 percent weaker in below-median cities, and the difference remains statistically significant. While this adjustment does not rule out segmentation by occupation within industry, the very modest change

where ϕ is the Mexican share of employment, var(L̇n) and var(L̇m) are the variance in labor demand shocks in the native and Mexican segments of the labor market, and cov(L̇n, L̇m) is their covariance. in observed smoothing when accounting for the substantial differences in natives’ and Mexicans’ industry distributions (see Appendix Figure A-6) suggests that labor market segmentation is an unlikely explanation for the differences between these two sets of cities.

Figure A-6.

Employment Shares by Industry Among Low-Skilled Men, Native- and Mexican-Born, 2006

Sources: Authors’ calculations from the 2006 American Community Survey. See text for individual sample restrictions. This figure reports information for men with no more than a high school education. See Figure A-5 for industry employment changes used to sort categories.

As a second alternative, we consider the possibility that some other unobserved factor causes some local labor markets to adjust to shocks more easily and that this other factor is correlated with the Mexican share of the low-skilled population. Perhaps Mexicans are attracted to local economies that are more flexible on a number of other dimensions including differences in local regulations and capital flexibility. Under this alternative, natives’ outcomes would have been smoother in these cities even in the absence of a large Mexican population. We address this hypothesis by repeating the smoothing analysis for highly skilled native-born men. Because we do not expect low-skilled Mexican mobility to affect outcomes for higher skilled workers, any differential incidence of local shocks among this skill group would suggest the presence of such an unobserved factor.

Panel (d) of Table 5 reports the relationship between changes in highly skilled native employment rates and labor demand shocks, calculated using highly skilled native men's industry employment distribution. We maintain the same classification of cities into above- and below-median Mexican population share (among low-skilled workers) used in the previous panels. There is no evidence that the incidence of employment shocks is any different for highly skilled workers in the two groups of cities. Thus, there is no support for the hypothesis that the labor markets with higher Mexican population share are more able to absorb labor demand shocks in general.48

This set of results therefore implies that the presence of substantial Mexican-born population insulates less skilled natives from the effects of local labor demand shocks. This is an important finding, as it indicates very different outcomes for natives living in cities facing similar labor demand shocks but with different Mexican population shares. Importantly, the smoothing result applies both to relatively positive and relatively negative shocks, with the presence of Mexicans improving outcomes for natives in the hardest hit markets and depressing outcomes for natives in the most positively affected locations.

4.2.3 Migration as the Smoothing Mechanism

The preceding results show that cities with a large Mexican population experienced smoother labor market outcomes among native low-skilled workers. We now discuss whether this smoothing is likely the consequence of equalizing migration or whether larger Mexican populations affect the incidence of labor demand shocks and native employment through some other mechanism. Consider the following identity demonstrating how the Mexican employment share, ϕc, influences the relationship between native employment probability, , and the local employment shock.49

| (6) |

The last term on the right hand side is the native population response, which the results in Section 3 show is approximately zero on average.50 The term in parentheses captures the differential equilibrium incidence of local job losses on native and Mexican workers, and it must be negative to be consistent with a weaker relationship between changes in natives’ employment probabilities and local employment shocks in cities with larger Mexican shares. Thus, in equilibrium, following job losses, turnover, and any migration responses, local employment declines are disproportionately reflected in declining local employment of Mexican-born workers.

This is precisely what one would expect if Mexican mobility had a direct effect on natives’ employment probability. By leaving (or failing to enter) the most depressed local markets, Mexican workers absorb a disproportionate share of the local employment decline, and natives’ share of employment rises as a result. To reinforce this interpretation, we show that it implies a degree of smoothing that is comparable to that observed in the data. Suppose that less skilled natives and Mexicans are perfect substitutes, in the sense that they are indistinguishable to employers. In this case, a given decline in overall employment will decrease equilibrium employment probabilities identically for both nativity groups, and differential employment changes will be driven by differ ential population changes.51 Under this interpretation, one can predict the amount of smoothing using employment shares and mobility responses. Indexing cities with Mexican population shares above and below the median by a and b respectively, plugging the estimated mobility responses into (6), and differencing across the two groups of cities yields the following expression:

| (7) |

Implementing this calculation yields a predicted gap of −0.29, which is similar in scale to the difference in slopes reported in panel (c) Table 5.52 Thus, the observed scale of smoothing is consistent with the prediction of a simple model of differential mobility and labor market competition between less skilled native-born and Mexican born workers.53

Taken as a whole, the results in the section imply that Mexican immigrants’ willingness to move away from the hardest hit cities and toward the least affected cities substantially reduced geographic inequality during the Great Recession. Further, their mobility exerted an equilibrating influence on the employment rates of native-born workers in addition to smoothing outcomes among the Mexican low-skilled population. Mexican mobility therefore provides an implicit form of insurance to native workers by transferring native employment probability from cities with relatively strong demand to cities experiencing the largest negative shocks.

5 Pre-Recession Analysis

In this section, we examine whether the differential population responses and associated smoothing that occurred during the Great Recession were similarly operative during the preceding boom (2000-2006). As discussed previously, OLS regressions of population changes on employment changes are likely appropriate only in an environment like the Great Recession, where adjustment to demand shocks occurred primarily through employment rather than wages. As this feature was not present during the boom, Table 6 presents Bartik IV specifications for 2000-2006, following Table 4.54 In this earlier time period, high-skilled workers of both genders are more responsive than were low-skilled workers, at least among the native-born. There is not as clear of a pattern among other groups, and the elasticities are, on the whole, estimated less precisely. Importantly, however, the strong positive elasticity among low-skilled Mexican-born men remains. Recall that the set of cities that experienced large demand increases during the boom period tended to have larger declines in the bust. Thus, this additional analysis directly supports interpreting the reversal of trends among the Mexican-born shown in Figures 1 and 2 as reflecting a substantial and rapid population response to local demand conditions in both time periods.

Table 6.

Population Response to Labor Demand Shocks 2000-2006: Bartik (1991) IV Estimates

| Dependent Variable: Change in log Population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Native-Born | Foreign-Born | Mexican-Born | Other Foreign-Born | |

| Panel A: Men, High-school or less | |||||

| IV Estimate | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.322** (0.145) | 0.127 (0.139) | 0.050 (0.584) | 0.872*** (0.221) | −0.142 (0.775) |

| P-value testing shock exogeneity | 0.026 | 0.029 | 0.005 | 0.638 | 0.004 |

| First Stage | |||||

| Predicted Change in log Employment | 3.856*** (0.984) | 4.005*** (0.856) | 3.467*** (1.277) | 4.207*** (1.129) | 3.101** (1.447) |

| Partial F Statistic | 15.37 | 21.92 | 7.368 | 13.87 | 4.590 |

| Panel B: Men, Some college or more | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.356** (0.139) | 0.296* (0.165) | 0.040 (0.421) | 1.495* (0.767) | −0.090 (0.454) |

| P-value testing shock exogeneity | 0.998 | 0.965 | 0.003 | 0.330 | 0.001 |

| First Stage | |||||

| Predicted Change in log Employment | 3.485*** (1.084) | 3.447*** (1.018) | 3.777*** (1.377) | 3.165*** (1.049) | 3.865*** (1.433) |

| Partial F Statistic | 10.33 | 11.47 | 7.523 | 9.109 | 7.272 |

| Panel C: Women, High-school or less | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.367 (0.227) | 0.232 (0.234) | −0.266 (0.707) | 0.561 (0.382) | −0.076 (0.707) |

| P-value testing shock exogeneity | 0.051 | 0.139 | 0.001 | 0.466 | 0.007 |

| First Stage | |||||

| Predicted Change in log Employment | 2.759*** (0.812) | 2.837*** (0.756) | 2.961*** (0.892) | 3.648*** (0.742) | 2.623** (1.080) |

| Partial F Statistic | 11.55 | 14.07 | 11.02 | 24.15 | 5.898 |

| Panel D: Women, Some college or more | |||||

| Change in log of Group-Specific Employment | 0.492** (0.240) | 0.422* (0.244) | −0.142 (0.665) | 0.455 (0.842) | −0.240 (0.695) |

| P-value testing shock exogeneity | 0.453 | 0.637 | 0.018 | 0.598 | 0.016 |

| First Stage | |||||

| Predicted Change in log Employment | 2.603** (1.291) | 2.662** (1.279) | 2.637* (1.366) | 2.076** (0.855) | 2.737* (1.438) |

| Partial F Statistic | 4.065 | 4.335 | 3.724 | 5.897 | 3.624 |

Each listed coefficient represents a separate instrumental variables regression of the change in log(population) from 2000 to 2006 for the relevant group (from the American Community Survey) on the change in log(group-specific employment) from County Business Patterns data over the same period, using the demographic group's industry mix. All regressions include an intercept term, 95 city observations, and the enclave control listed in Column (2) of Table A-1. Observations are weighted by the inverse of the estimated sampling variance of the dependent variable (see appendix for details). Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors in parentheses

significant at the 1% level

5%

10%.

We use the predicted change in log(employment), based on Bartik (1991) and described in the text, as an instrument for the change in log(group-specific employment). The listed “p-value testing shock exogeneity” is from a test of the null hypothesis that the OLS and IV slope coefficients are equal to each other. The first-stage coefficient on the instrument and the partial F statistic are reported below the corresponding IV estimate.

Table 7 presents smoothing results for the pre-Recession period, splitting the city sample into those above and below median Mexican-born population share, as in Table 5. Again, we use the Bartik instrument to predict changes in local employment. In panels (a)-(c), the results continue to show that less-skilled men's local outcomes are less tied to local shocks in cities with greater access to Mexican-born workers, although the differences are not statistically significantly different from zero in the latter two panels. Importantly, the results in panel (d) continue to show no substantial difference in smoothing in the high-skilled labor market based on Mexican-born population share. Thus, the phenomena of large population responses among the Mexican-born and the resulting smoothing occur to some extent regardless of whether the economy is growing or shrinking, although it is reasonable to conclude that the smoothing effect may be especially operative during downturns.

Table 7.

Mexican Mobility Smooths Employment Outcomes 2000-2006: Bartik (1991) IV Estimates

|

dependent variable: change in log employment/population (ACS)

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City's Mexican population share |

|||

| below-median | above-median | difference | |

| (a) dependent variable sample: less-skilled men | |||

| change in log employment for less-skilled men (CBP) | 0.526** (0.241) | −0.108 (0.215) | −0.634** (0.323) |

| (b) dependent variable sample: native less-skilled men | |||

| change in log employment for less-skilled men (CBP) | 0.285*** (0.078) | 0.175 (0.128) | −0.111 (0.150) |

| (c) dependent variable sample: native less-skilled men | |||

| change in log employment for less-skilled native men (CBP) | 0.289*** (0.079) | 0.190 (0.142) | −0.099 (0.162) |

| (d) dependent variable sample: native high-skilled men | |||

| change in log employment for high-skilled native men (CBP) | 0.140** (0.063) | 0.105* (0.063) | −0.035 (0.089) |

Examines the relationship between labor market outcomes (changes in employment probability) and changes in payroll employment separately for cities with above- and below-median Mexican population share to demonstrate the smoothing effect of Mexican mobility. This table reports the results of specifications run using data from 2000-2006 for both the dependent and independent variables. Smaller coefficients indicate more smoothing. We use the predicted change in log(employment), based on Bartik (1991) and described in the text, as an instrument for the change in log(group-specific employment). Panel (a) examines the relationship between low-skilled employment shocks and low-skilled men's employment probability. Panel (b) examines the relationship between low-skilled employment shocks and low-skilled native men's employment probability. Panel (c) examines the relationship between low-skilled native employment shocks and low-skilled native men's employment. Panel (d) examines the relationship between high-skilled native employment shocks and high-skilled native men's employment.

6 Extensions and Discussion

In this section we study the mechanisms through which the less skilled Mexican-born population adjusted to labor demand shocks and investigate some hypotheses for why Mexicans respond so much more strongly than similarly skilled natives.

6.1 Channels of Population Adjustment

A city's Mexican-born working-age population, , can change between 2006 and 2010 through five channels: 1) arrivals from abroad after 2006, 2) migration between cities within the U.S., 3) departures from the U.S., 4) aging in or out of the sample, and 5) entering or leaving the sample due to changing schooling status. Here, we measure the importance of each channel in driving the strong population responses among less skilled Mexican-born men. Channels 1 and 4 are directly observable, as the ACS records immigrants’ age and year of arrival. Channel 5 likely makes a very small contribution, particularly among the less skilled working-age immigrants in our sample. Channels 2 and 3 are more difficult to separate in the data; we return to this below.

We begin by examining changes in the number of Mexican-born individuals who arrived in the U.S. before and after 2007. Thus, we partition a city's change in Mexican population as (suppressing city subscripts):

| (8) |

In words, the change in the Mexican-born population consists of the number of immigrants who arrived in 2007 or later () plus the change in the number of immigrants who arrived in the U.S. in 2006 or earlier (). Notice that is simply the resident Mexican population in 2006. Dividing both sides of (8) by Nm,2006, one can decompose the proportional change in Mexican population into components resulting from new arrivals (channel 1) and from reallocation of existing residents (channels 2-5).

We therefore estimate slightly modified versions of Equation (1) for less skilled Mexican men, using the proportional change in the population () and each component thereof as dependent variables, rather than the change in log population. The results are presented in Table 8. Column (1) reproduces the overall elasticity for low-skilled Mexican men shown in Figure 1; column (2) shows the slight change in the magnitude from the change in the dependent variable. The next two columns additively decompose that estimate into components coming from new arrivals and movement of existing residents. The coefficient in column (3) implies that 22 percent of the reallocation occurred through differential inflows of new immigrants in response to differential demand shocks. Note that fewer than 22 percent of Mexican-born immigrants living in the US in 2010 arrived during the preceding five years; thus these new arrivals account for more than their “fair share” of the reallocation.55 It is likely that during periods with larger immigration inflows, this channel would account for a larger share of overall adjustment, but net migration inflows approached zero by the end of the decade (Passel, Cohn and Gonzalez-Barrera 2012). The remaining 78 percent of the reallocation occurred among existing residents (channels 2-5), and this aggregate effect is reflected in the coefficient in column (4). Column (5) provides a direct estimate of the contribution of net aging in (channel 4); as expected the contribution of this channel is negligible.56

Table 8.

Channels of Population Response: Male Low-Skilled Mexican-Born Population

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Elasticity (Chg. In log Pop..) | Total Elasticity (Prop. Chg. In Pop..) | New Arrival Sorting | Change in Pre-2007 Arrivals | Net Aging In | Internal Inflows | Internal Outflows | |

| Change in log Employment | 0.569*** (0.202) | 0.528*** (0.177) | 0.115*** (0.024) | 0.413** (0.174) | −0.025 (0.019) | 0.025 (0.060) | 0.087** (0.034) |

| Constant | 0.028 (0.035) | 0.034 (0.033) | 0.072*** (0.007) | −0.039 (0.031) | 0.005 (0.007) | 0.090*** (0.018) | −0.066*** (0.007) |

| Share of Total Elasticity | N/A | 100.0% | 21.8% | 78.2% | −4.8% | 4.7% | 16.5% |

| Share of Pre-2007 Elasticity | N/A | N/A | N/A | 100.0% | −6.1% | 6.1% | 21.1% |

| R-squared | 0.203 | 0.178 | 0.132 | 0.142 | 0.013 | 0.001 | 0.055 |

Column (1) reproduces the corresponding estimate from Table 2. Column (2) replaces the change in log(population) with the proportional change in population. As described in the text, Columns (3)-(7) decompose the overall response in column (2) into different migration components. All other specification details are identical to Table 2. The dependent variable in column (7) is the growth in the local population due to internal outflows, i.e. the negative of the proportional change in population due to outflows. A test of the null hypothesis that the sum of the coefficients in columns (6) and (7) is zero returns a p-value of 0.108.

Most of the reallocation therefore occurred through migration by those already resident by 2006. The large share of reallocation among existing immigrants is an important finding, as the majority of the previous literature focuses only on location choices among newly arriving immigrants. Decomposing this channel further is difficult, however, because there are no available data sources that allow reliable measurement of return migration flows to Mexico separately by US city during this time period.57 In addition, the ACS asks respondents only about internal movement over the past year; the five year mobility question, standard in prior decennial censuses, does not appear in the ACS. Thus, it is not possible to precisely decompose pre-2007 arrivals observed in the 2010 ACS into those who lived in the same city in 2006 and those who lived in another US location. Nevertheless, one can construct imperfect estimates of internal migration by aggregating internal inflows and outflows from each successive annual ACS survey. The regressions in columns (6) and (7) are based on this technique, and they reveal that, together, measured internal migration can explain roughly 20 percent of the overall reallocation, with internal outflows relatively more important. Given the lack of a direct measure of return migration and the fairly wide confidence intervals on each of the other components, it is difficult to precisely estimate the relative contribution of return migration. It is clear, though, that both migration internal to the US and return migration to Mexico were important components of the overall local supply elasticity, consistent with the descriptive migration rates for Mexican-born individuals reported in Table 1.

6.2 Why are the Mexican-Born More Responsive?

We now consider potential explanations for the sharp differences in population elasticity between native-born and Mexican-born less skilled workers. Recall from Table 1 that, although the less skilled Mexican-born are less likely than similarly skilled natives to migrate within the U.S., their much higher rate of international mobility implies a substantially larger overall probability of migrating. This difference may simply reflect a process of self-selection in which the immigrant pool consists primarily of highly mobile individuals.

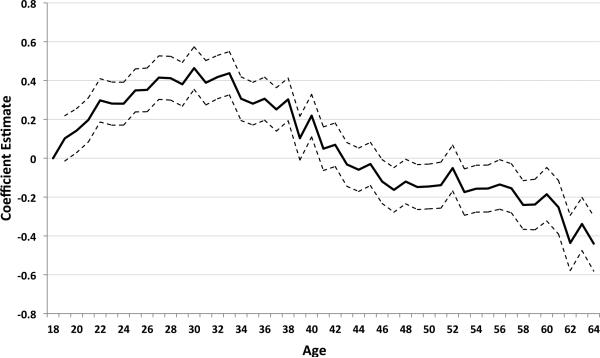

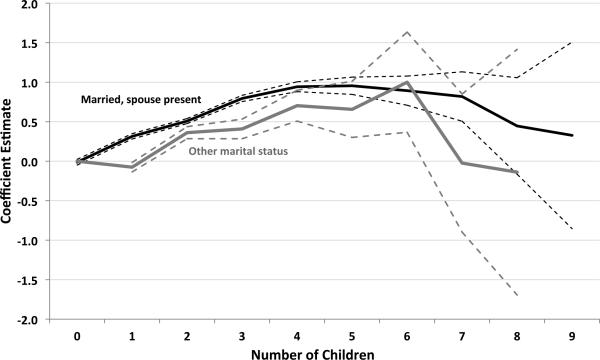

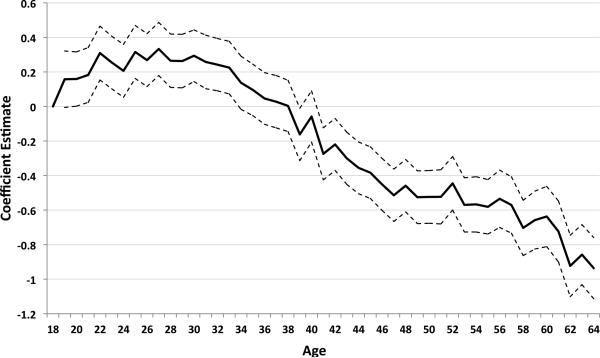

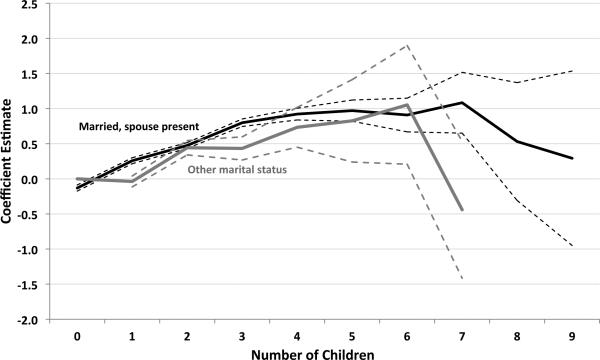

Thus, to some extent, immigrants’ demographics and other observable characteristics may account for their increased responsiveness compared to natives. To investigate this possibility, we first estimate probit regressions in which we predict Mexican-born status based on either age, marital status, detailed educational attainment, home ownership, or all of these factors together.58 We then use the resulting propensity score weights to calculate city-level populations and industry shares (to calculate the relevant employment changes) using native workers whose observable characteristics, on average, match those of the Mexican-born. We then repeat our main mobility analysis for this reweighted group of natives. The results are shown in columns (3)-(7) of Table 9, with the baseline results for less skilled Mexican-born and native-born men provided for reference in columns (1) and (2). Even after making these adjustments, we find no evidence that natives move toward cities with better job prospects.

Table 9.

Propensity Score Reweighting of Less Skilled Native Men to Match Less Skilled Mexican-Born Men's Observables

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Reweighting |

Reweighted Natives Based on Listed Covariates |

||||||||

| Mexican-Born | Native-Born | Skill Only | Age Only | Rent vs. Own Only |

Family Structure Only |

All Prior Covariates |

Outside Birth State |

Outside Birth State and Other Covariates |

|

| Proportional Change in Group-Specific Employment | 0.569*** (0.202) | 0.041 (0.072) | −0.028 (0.101) | 0.119 (0.084) | −0.047 (0.094) | 0.047 (0.067) | 0.014 (0.122) | 0.211* (0.119) | 0.385 (0.282) |

| Constant | 0.569*** (0.202) | −0.013 (0.010) | −0.022 (0.015) | −0.022** (0.011) | 0.010 (0.012) | −0.017 (0.011) | −0.002 (0.022) | −0.026 (0.020) | −0.018 (0.054) |

| R-squared | 0.203 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.028 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.031 | 0.023 |

Columns (1) and (2) reproduce corresponding estimates from Table 2 for Mexican-born and native-born less skilled men. Columns (3)-(7)present population responses for natives, reweighted to match Mexican-born individuals’ based on the listed characteristics. Column (8)provides population responses among natives living outside of their state of birth, and in column (9) these populations are further reweighted to match the same set of covariates as in column (7). All other specification details are identical to Table 2. See text and appendix for details.

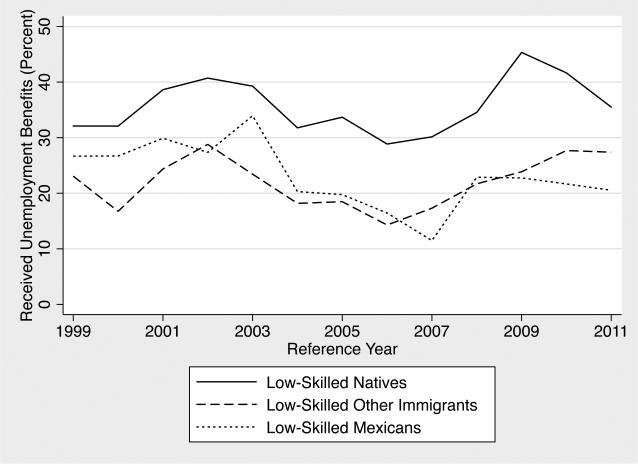

We then consider the possibility that natives who have previously made long-distance moves may be similarly more responsive. Column (8) presents the results of a version of column (2), but with population changes and city-level employment changes calculated based on the subset of low-skilled natives who are living outside of their state of birth. The estimated elasticity in this group is substantially larger than the elasticity among all natives, and the coefficient is marginally statistically significant. In column (9), we further reweight the population used in column (8) to reflect all of the covariates included in column (7). This specification yields the largest point estimate among any native population, although it is imprecisely estimated. Thus, it appears that part of the strong mobility responses among the Mexican-born derives from self-selection, although the differences do not appear to be entirely driven by differences in demographics.