Summary

Interstitial pneumonia (IP) is a chronic progressive interstitial lung disease associated with poor prognosis and high mortality. However, the pathogenesis of IP remains to be elucidated. The aim of this study was to clarify the role of pulmonary γδT cells in IP. In wild‐type (WT) mice exposed to bleomycin, pulmonary γδT cells were expanded and produced large amounts of interferon (IFN)‐γ and interleukin (IL)‐17A. Histological and biochemical analyses showed that bleomycin‐induced IP was more severe in T cell receptor (TCR‐δ‐deficient (TCRδ–/–) mice than WT mice. In TCRδ–/– mice, pulmonary IL‐17A+CD4+ Τ cells expanded at days 7 and 14 after bleomycin exposure. In TCRδ–/– mice infused with γδT cells from WT mice, the number of pulmonary IL‐17A+ CD4+ T cells was lower than in TCRδ–/– mice. The examination of IL‐17A–/– TCRδ–/– mice indicated that γδT cells suppressed pulmonary fibrosis through the suppression of IL‐17A+CD4+ T cells. The differentiation of T helper (Th)17 cells was determined in vitro, and CD4+ cells isolated from TCRδ–/– mice showed normal differentiation of Th17 cells compared with WT mice. Th17 cell differentiation was suppressed in the presence of IFN‐γ producing γδT cells in vitro. Pulmonary fibrosis was attenuated by IFN‐γ‐producing γδT cells through the suppression of pulmonary IL‐17A+CD4+ T cells. These results suggested that pulmonary γδT cells seem to play a regulatory role in the development of bleomycin‐induced IP mouse model via the suppression of IL‐17A production.

Keywords: gamma delta T cell, IL‐17A, interferon‐γ, interstitial pneumonia

Introduction

Interstitial pneumonia (IP) is a chronic progressive interstitial lung disease associated with poor prognosis and high mortality 1. IP is an intractable disease induced by various factors such as autoimmune diseases, drugs, exposure to certain occupational hazards and environmental factors 2. For example, the chemotherapy with bleomycin and busulphan is reported to cause lung fibrosis in some patients 3. Following the interstitial inflammation, fibroblast proliferation within both the interstitium and alveolar space is often observed. However, the pathogenesis of IP remains to be elucidated.

In mice, pulmonary fibrosis can be induced by the administration of bleomycin, silica particles or Bacillus subtilis. Bleomycin‐induced IP mouse is a typical murine model of pulmonary fibrosis 4. In this model, exposure to bleomycin induces an acute inflammatory response that lasts up to 8 days and is followed by fibrogenic changes, resulting in the deposition of collagen and distortion of the lung structure within 28 days. Thus, the acute inflammation phase switches to the fibrosis phase at approximately day 10 after bleomycin exposure.

Recently, the functional role of gamma delta (γδ) T cells was reported in several IP mouse models 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. The γδT cells can produce a wide variety of cytokines, chemokines and growth factors and play an important role in the regulation of the initial immune response to several pathogens by influencing the migration and activity of neutrophils, macrophages, natural killer (NK) and T helper (Th) cells 10. In fact, γδT cells were considered to have regulatory roles in bleomycin‐induced IP 5, 11. However, the regulatory function of γδT cells in the development of pulmonary fibrosis is not yet clear. Previous studies showed that γδT cells were able to produce both interferon (IFN)‐γ and interleukin (IL)−17A 12. IFN‐γ is reported to inhibit fibroblast proliferation and production of collagen in vitro as well as the development of pulmonary fibrosis in vivo 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18. Conversely, IL‐17A promotes fibroblast proliferation and production of several fibrotic factors in vitro 19. IL‐17A‐deficient mice attenuated bleomycin‐induced airway inflammation and pulmonary fibrosis 20, 21. Thus, the roles of IFN‐γ and IL‐17A are thought to have opposite effects in the progression of pulmonary fibrosis.

In humans, several reports showed that γδT cells play a role in the development of pulmonary fibrosis 22, 23. We also reported that CD161‐expressing γδT cells play a regulatory role in IP in patients with systemic sclerosis 24. To our knowledge, however, there is only little or no information about the properties and functional characteristics of γδT cells in pulmonary fibrosis.

The present study was designed to clarify the regulatory role of γδT cells in the development of bleomycin‐induced IP, with a special focus on the roles of IFN‐γ and IL‐17A.

Materials and methods

Mice and exposure to bleomycin

C57BL/6 [wild‐type (WT)] mice were purchased from Charles River Japan Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). T cell receptor (TCR)δ‐deficient (TCRδ–/–) mice 25 with a C57BL/6 background were provided by Riken BRC, a participant in the National Bio‐Resource Project of the MEXT, Japan. IFN‐γ‐deficient (IFN‐γ–/–) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. IL‐17A‐deficient (IL‐17A–/–) mice were kindly provided by Professor Y. Iwakura (Tokyo University of Science). Only female mice were used in this study. The animals were kept under specific pathogen‐free conditions and studied at 8–10 weeks of age. The Committee on Institutional Animal Care and Use at Tsukuba University approved all the experimental protocols. Bleomycin (1·25 mg/kg; Nippon Kayaku, Tokyo, Japan) dissolved in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) was administrated intratracheally in this study. Briefly, mice were sedated with isoflurane, attached to a tilting table. Then, the trachea was cannulated with auriscope (WelchAllyn, Skaneateles Falls, NY, USA) and bleomycin was infused directly into the lungs.

Staining and flow cytometry

Pulmonary lymphocytes were isolated from the lungs using the following method. The lungs were perfused thoroughly with PBS to remove circulating blood cells. The dissected lungs were incubated with 1% collagenase D (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) in RPMI‐1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; BioWest, Miami, FL, USA), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 50 µM 2‐mercaptoethanol at 37°C for 1 h. Then, the lungs were minced and passed through nylon mesh to remove debris. The washed and recovered cells were subjected to Percoll PLUS (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) at 800 × g at room temperature for 20 min. The resultant interface containing pulmonary lymphocytes was recovered and washed with RPMI‐1640 medium. Cells were stained with the following monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐conjugated anti‐TCRγδ (clone: GL3), anti‐CD11c (N418), anti‐TCRβ (H57‐593), R‐phycoerythrin (PE)‐conjugated anti‐Gr‐1 (RB6‐8C5), anti‐TCRγδ (GL3), allophycocyanin (APC)‐conjugated anti‐CD3ε (145‐2C11), anti‐CD11b (M1/70) and peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP)/cyanin (Cy)5·5‐conjugated CD4 (GK1·5) mAbs [all from Biolegend (San Diego, CA, USA)]. Intracellular staining for forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3) was performed after fixation and permeabilization according to the protocol supplied by the manufacturer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). Dead cells were stained with Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 780 (eBioscience). The stained cells were analysed on fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) Verse flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA) and data were processed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA).

Intracellular cytokine staining

Pulmonary lymphocytes from WT and TCRδ–/– mice were prepared as described above. Cells were stimulated with phorbol 12‐myristate 13‐acetate (PMA, 50 ng/ml; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), ionomycin (1 μg/ml; Sigma) and GolgiStop (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) in 96‐well round‐bottomed plates for 6 h. Cells were first stained for a cell surface marker, then fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Pharmingen), before further immunostaining with PerCP/Cy5·5‐conjugated anti‐IFN‐γ (XMG1·2) and PE/Cy7‐conjugated IL‐17A (TC11‐18H10·1). Cells were analysed with FACS Verse flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and data were analysed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Histological examination

The lung tissues were perfused with formalin. The trachea was cannulated, and formalin (0·5 ml) was infused into the lungs. Fixed lung tissues were removed and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 µm) were stained with Masson's trichrome.

Quantitative image analysis (QIA)

The percentage area of fibrosis was quantified as described previously 4. Briefly, five randomly fields per slide were selected and detected blue‐stained collagen within each fields. The fraction of collagen areas for each field was averaged for each animal.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) analysis

The trachea was cannulated, and the lung was lavaged five times with 0·8 ml of cold PBS each. The BALF was centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min at 4°C.

Determination of soluble collagen by Sircol assay

The left lungs were minced and incubated with 1 ml of pepsin (0·1 mg/ml in 0·5 M acetic acid) at 4°C. After 24 h, samples were centrifuged at 10 000 × g and these supernatant recovered. Collagen content of the left lung and BALF was performed by Sircol assay according to the protocol supplied by the manufacturer (Biocolor, County Antrim, UK).

Cell proliferation and adoptive transfer of γδT cells

Pulmonary lymphocytes were harvested from WT and IFN‐γ–/– mice and stained with anti‐CD3, anti‐TCRδ and anti‐NK1·1 mAbs. Total γδT, NK1·1– γδT and NK1·1+ γδT cells were sorted using Moflo XDP (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The purity of each γδT cells in this experiment was greater than 90%. The purified γδT cells were cultured with IL‐2 (100U/ml), IL‐7 (20 ng/ml) and IL‐15 (20 ng/ml) for 12 days. Then, the expanded γδT cells were sorted using Moflo XDP (Beckman Coulter). One day after bleomycin exposure, purified expanded γδT cells were infused at 1 × 105 cells in total volume of 100 µl via the tail vein into TCRδ–/– mice.

Measurement of cytokines from γδT cells

The expanded NK1.1– γδT cells (1 × 105/ml) and NK1·1+ γδT cells (1 × 105/ml) were stimulated with 1 µg/ml of anti‐CD3 mAb (Biolegend) and 1 µg/ml of anti‐CD28 mAb (Biolegend). After 96 h, IFN‐γ and IL‐17A in the culture supernatants were evaluated by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). For intracellular cytokine staining, the expanded NK1·1– γδT cells (5 × 105/ml) and NK1·1+ γδT cells (5 × 105/ml) were co‐cultured with 1 µg/ml of anti‐CD3 mAb (Biolegend) and 1 µg/ml of anti‐CD28 mAb (Biolegend). After 96 h, IFN‐γ and IL‐17A from NK1·1– or NK1·1+ fractions were analysed by flow cytometry.

Isolation of CD4+ T cells and in‐vitro T cell cultures

Splenic CD4+ T cells were isolated by positive selection, using a magnetic‐activated cell sorter (MACS) system with anti‐CD4 monoclonal antibody (mAb; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). For Th17 cell differentiation, CD4+ cells (1 × 106/ml) were cultured in medium with 1 µg/ml of anti‐CD3 mAb (Biolegend), 1 µg/ml of anti‐CD28 mAb (Biolegend), 1 ng/ml of human transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β (R&D Systems), 20 ng/ml of mouse IL‐6 (eBioscience), 10 µg/ml of anti‐IFN‐γ mAb (Biolegend) and 10 µg/ml of anti–IL‐4 mAb (Biolegend). On day 4, the cells were restimulated for 6 h with 50 ng/ml of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and 500 ng/ml of ionomycin and used in the experiments.

Co‐culture with CD4+ and expanded γδT cells

CD4+ T cells (2 × 105/well) were co‐cultured with expanded γδT cells (1 × 104/well) in conditions of Th17 cell differentiation as above. On day 4, the cells were restimulated for 6 h with 50 ng/ml of phorbol myristate acetate and 500 ng/ml of ionomycin and used in the experiments.

Quantification of gene expression by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from isolated from lung tissues, and reverse‐transcribed into cDNA using RevertAidTM first‐strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Fermentas, Burlington, Ontario, Canada), according to the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. The cDNA samples were amplified with specific primers and fluorescence‐labelled probes for target genes. Specific primers and probes for TGF‐β, collagen type I alpha 1 (Col1a1) and glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were purchased from Applied Biosystems Japan (Tokyo, Japan). The amplified product genes were monitored on an ABI 7700 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems Japan). The quantitative PCR master mix was purchased from Applied Biosystems Japan. The final concentrations of the primers were 200 nM for each of 5′ and 3′ primers, and the final probe concentration was 100 nM. The thermal cycler conditions were 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, then 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Serial dilutions of a standard sample were incubated in every assay, and standard curves for the genes of interest and GAPDH genes were generated. All measurements were performed in duplicate. The gene expression level was calculated from the standard curve, and expressed relative to GAPDH gene expression.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as median and mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance using Student's t‐test. A P‐value less than 0·05 denoted the presence of a statistically significant difference. For multiple group comparisons, one‐way analysis of variance (anova) was performed, followed by the Tukey test. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

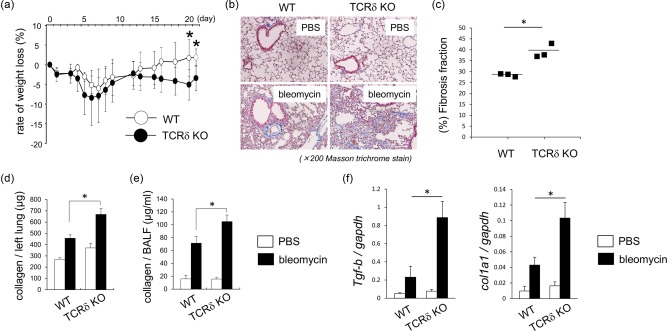

γδT cells suppress bleomycin‐induced IP using TCRδ–/– mice

To examine the effects of γδT cells in the progression of pulmonary fibrosis, WT and TCRδ–/– mice were treated with bleomycin. As shown in Fig. 1a, TCRδ–/– mice showed significant body weight loss compared with WT mice on days 20 and 21 after bleomycin exposure. Histological analysis showed that TCRδ–/– mice had thickened alveolar septa and ablation of alveolar space at day 21 compared with WT mice (Fig. 1b). Using the quantitative image analysis (QIA), the fibrosis fraction was significantly larger in TCRδ–/– mice compared with WT mice 21 days after bleomycin exposure (Fig. 1c). The amounts of collagen in lung tissues and BALF was significantly higher in TCRδ–/– mice than in WT mice 21 days after bleomycin exposure (Fig. 1d,e). Furthermore, the expression of TGF‐β and Col1a1 mRNA in lung tissues was significantly higher in TCRδ–/– mice than WT mice (Fig. 1f). These results indicate that the deficiency of γδT cells enhances the progression of bleomycin‐induced IP.

Figure 1.

Histological and biochemical analyses of wild‐type (WT) and T cell receptor (TCR)δ–/– mice exposed to bleomycin. (a) Change in body weight after bleomycin exposure in WT (n = 4) and TCRδ–/– mice (n = 7). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). *P < 0·05. (b) Lung tissues were obtained from WT (n = 3) and TCRδ–/– mice (n = 4) on day 21 after phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) or bleomycin exposure. Paraffin sections were stained with Masson's trichrome. Original magnification ×200. (c) Fibrosis fraction in WT (n = 3) and TCRδ–/– (n = 3) mice was measured on 21 days after bleomycin exposure by quantitative image analysis. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05. (d,e) The lung tissues and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were obtained from WT (n = 4) and TCRδ–/– mice (n = 7) on day 21 after bleomycin exposure and collagen production was determined. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05. (f) Lung tissues were harvested from WT (n = 4) and TCRδ–/– mice (n = 7) on day 21 after bleomycin exposure. Lung mRNA was extracted and the expression of transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β and col1a1 mRNA was analysed by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05.

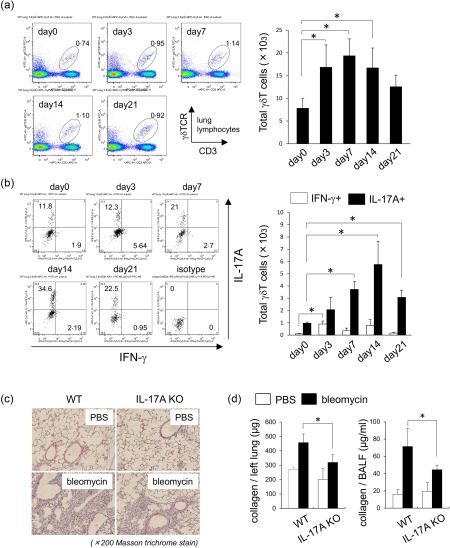

Expansion of pulmonary γδT cells in bleomycin‐induced IP

To examine the phenotype of pulmonary γδT cells following exposure to bleomycin, pulmonary lymphocytes were analysed by flow cytometry (FCM). As shown in Fig. 2a, the number of pulmonary γδT cells increased at days 3, 7 and 14 after bleomycin exposure. Then, we examined the expression of IFN‐γ and IL‐17A on pulmonary γδT cells. At 3 days after bleomycin exposure, IFN‐γ‐producing (IFN‐γ+) γδT cells expanded in lung tissues (Fig. 2b). In comparison, at 7, 14 and 21 days after bleomycin exposure, the number of IL‐17A+ γδT cells increased exponentially in lung tissues (Fig. 2b). These results suggest that pulmonary γδT cells produce mainly IL‐17A at the fibrosis phase after bleomycin exposure. To confirm the role of IL‐17A in bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis, experiments were performed in IL‐17A‐deficient (IL‐17A–/–) mice. The collagen accumulation was reduced on day 21 after bleomycin exposure in IL‐17A–/– mice (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, the amounts of collagen in lung tissues and BALF on 21 days after bleomycin exposure was significantly lower in IL‐17A–/– mice than in WT mice (Fig. 2d). The above findings suggest that IL‐17A is an exacerbation factor in the development of pulmonary fibrosis. Conversely, pulmonary γδT cells play an inhibitory role in the development of pulmonary fibrosis despite the production of inflammatory cytokine such as IL‐17A.

Figure 2.

Phenotypes of pulmonary γδT cells in bleomycin‐induced fibrosis. (a) Pulmonary lymphocytes were harvested from wild‐type (WT) mice (n = 3) on days 0, 3, 7, 14 and 21 after intratracheal instillation of bleomycin. Cells were stained for CD3ε, γδ T cell receptor (TCR)δ and analysed by flow cytometry. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Data are mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). *P < 0·05. (b) Pulmonary lymphocytes were harvested from WT mice (n = 3) on days 0, 3, 7, 14 and 21 after bleomycin exposure and stimulated by phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)/ionomycin for 6 h. Cells were stained for CD3ε, γδTCR, interferon (IFN)‐γ, interleukin (IL)−17A and analysed by flow cytometry. CD3ε+ γδTCR+ cells were gated. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05. (c) Lung tissues were removed from WT (n = 3) and inrerleukin (IL)−17A–/– mice (n = 4) on day 21 after bleomycin exposure. Paraffin sections were stained with Masson's trichrome. Original magnification ×200. (d) Lung tissues and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were obtained from WT (n = 3) and IL‐17A–/– mice (n = 4) on day 21 after bleomycin exposure. Collagen production was determined by sircol assay. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05.

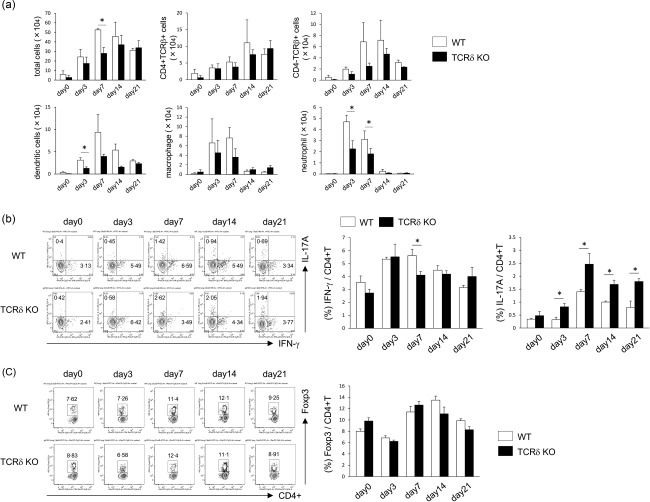

γδT cells induce Th1 cells but reduce Th17 cells

The number of total cells in BALF was significantly lower in TCRδ–/– mice compared with WT mice at 7 days after bleomycin exposure (Fig. 3a). The numbers of dendritic cells and neutrophils in BALF were significantly lower in TCRδ–/– mice than WT mice at days 3 and 7. These results suggest that γδT cells induce infiltration of dendritic cells and neutrophils into the lung, resulting in severe inflammation.

Figure 3.

Inflammatory and cellular changes in lung tissues of mice exposed to bleomycin. (a) wild‐type (WT) (n = 3) and T cell receptor (TCR)δ–/– mice (n = 4) were infused intratracheally with bleomycin. At days 0, 3, 7, 14 and 21, the number of total, CD4+TCRβ+, CD4–TCRβ+, dendritic cells (CD11c+), macrophages (CD11c–CD11b+Gr‐1–) and neutrophils (CD11c–CD11b+Gr‐1+) was analysed by flow cytometry (FCM). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). *P < 0·05. (b) Pulmonary lymphocytes were harvested from WT (n = 3) and TCRδ–/– mice (n = 4) on days 0, 3, 7, 14 and 21 after bleomycin exposure and stimulated by phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)/ionomycin for 6 h. Cells were stained for TCRβ, CD4, interferon (IFN)‐γ, interleukin (IL)−17A and analysed by flow cytometry. CD4+TCRβ+ cells were gated. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05. (c) Pulmonary lymphocytes were harvested from WT (n = 3) and TCRδ–/– mice (n = 4) on days 0, 3, 7, 14 and 21 after bleomycin exposure. Cells were stained for TCRβ, CD4, forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3) and analysed by flow cytometry. CD4+TCRβ+ cells were gated. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05.

We also examined the roles of IFN‐γ+CD4+ T and IL‐17A+CD4+ T cells in the development of pulmonary fibrosis. After exposure to bleomycin, the proportion of IFN‐γ+CD4+ T cells in lung tissues at day 3 was significantly lower in TCRδ–/– mice than WT mice (Fig. 3b). In contrast, the proportion of IL‐17A+CD4+ T cells at days 3, 7, 14 and 21 days after bleomycin exposure was significantly higher in TCRδ–/– mice. The proportion of pulmonary regulatory T cells (Treg) [forkhead box protein 3 (Foxp3+)CD4+ T] cells was not significantly different between WT and TCRδ–/– mice (Fig. 3c). These findings suggest that γδT cells seem to induce IFN‐γ+CD4+ T cells and suppress IL‐17A+CD4+ T cells in mice with bleomycin‐induced IP.

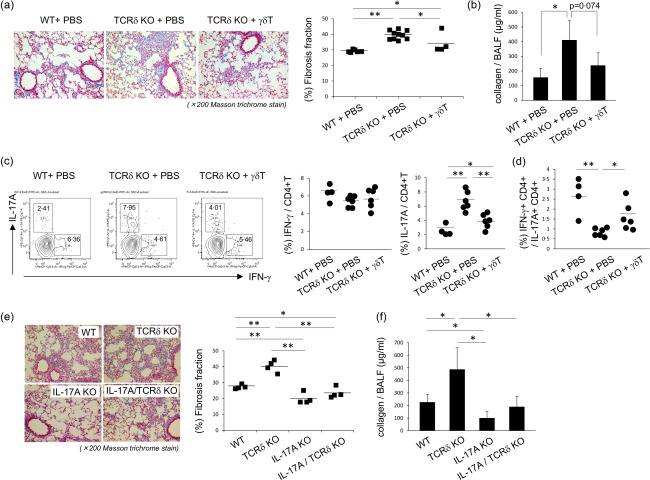

γδT cells attenuate bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis via the suppression of Th17 cells

To confirm the role of γδT cells in bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis, we transferred γδT cells expanded by IL‐2, IL‐7 and IL‐15 into bleomycin‐treated TCRδ–/– mice. As shown in Fig. 4a, γδT cells reduced collagen accumulation and fibrosis fraction in TCRδ–/– mice. The amounts of collagen in BALF was not decreased significantly, but tended to be lower in TCRδ–/– mice infused with γδT cells compared with control mice (Fig. 4b). In γδT cells infused TCRδ–/– mice, pulmonary IL‐17A+ CD4+ T cells were significantly lower compared with control mice, whereas pulmonary IFN‐γ+CD4+ T cells were not (Fig. 4c). After exposure of TCRδ–/– mice to bleomycin, pulmonary CD4+ T cells were inclined towards IL‐17A+CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4d). The transfer of γδT cells in TCRδ–/– mice improved the ratio of IL‐17+CD4+ T cells to IFN‐γ+CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

Improvement of pulmonary fibrosis by γδT cells. (a) Wild‐type (WT) mice were harvested and pulmonary γδT cells were purified, as described in Materials and methods. Purified pulmonary γδT cells were expanded by interleukin (IL)−2, IL‐7 and IL‐15 for 12 days. Then, the expanded γδT cells were transferred into T cell receptor (TCR)δ–/– mice (1 × 105/mice). Six WT mice received phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), 10 TCRδ–/– mice received PBS and four TCRδ–/– mice received γδT cells. The lung tissues were removed on day 21 after bleomycin exposure. Paraffin sections were stained with Masson's trichrome. Original magnification ×200. Fibrosis fraction was measured by quantitative image analysis, as described in Materials and methods. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01. (b) Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was obtained on day 17 after bleomycin exposure and collagen production was determined. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05. (c) At 18 days after bleomycin exposure, pulmonary lymphocytes were harvested and then stimulated with phorbol myristate actate (PMA)/ionomycin for 6 h. Cells were stained for CD3ε, CD4, interferon (IFN)‐γ, IL‐17A and analysed by flow cytometry. CD4+CD3ε+ cells were gated. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01. (d) At 18 days after bleomycin exposure, pulmonary lymphocytes were harvested and then stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 6 h. Cells were stained by CD3ε, CD4, IFN‐γ, IL‐17A and analysed by flow cytometry (FCM). Data are the proportion of IFN‐γ+CD4+T/IL‐17A+ CD4+ T cells in each mouse. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P <0·05, **P < 0·01. (e) WT (n = 4), TCRδ–/– (n = 4), IL‐17A–/– (n = 4) and IL‐17A/TCRδ–/– (n = 4) mice were treated with bleomycin. After 21 days, paraffin sections were stained with Masson's trichrome. Original magnification ×200. Fibrosis fraction was measured by quantitative image analysis. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01. (f) WT (n = 4), TCRδ–/– (n = 4), IL‐17A–/– (n = 4) and IL‐17A/TCRδ–/– (n = 4) mice were treated with bleomycin. BALF was obtained on day 21 after bleomycin exposure and collagen production was determined. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *p<0.05.

To examine whether IL‐17A plays essential roles in the development of pulmonary fibrosis in TCRδ–/– mice, IL‐17A–/–TCRδ–/– mice were treated with bleomycin. At day 21, collagen accumulation in lung tissues and collagen production in BALF were significantly lower in IL‐17A–/–TCRδ–/– mice than TCRδ–/– mice (Fig. 4e,f). However, pulmonary collagen accumulation and production were not significantly different between IL‐17A–/– and IL‐17A–/–TCRδ–/– mice. These findings support the notion that γδT cells suppressed pulmonary fibrosis through the suppression of IL‐17+CD4+ T cells.

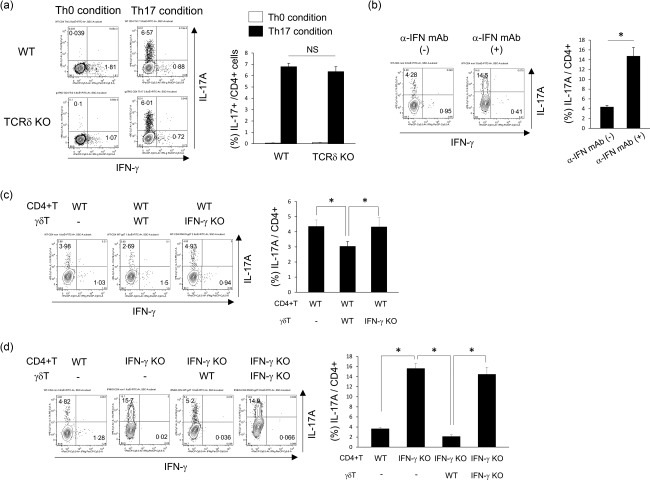

γδT cells suppress Th17 cell differentiation in vitro via IFN‐γ production

To examine whether γδT cells affect Th17 cell differentiation, CD4+ T cells were cultured under several conditions in vitro. CD4+ cells isolated from TCRδ–/– mice showed normal differentiation of Th17 cells compared with WT mice (Fig. 5a). To investigate the effects of IFN‐γ in Th17 cell differentiation, we used IFN‐γ neutralization antibodies. The number of IL‐17A+CD4+ T cells was significantly higher in the presence of anti‐IFN‐γ mAb (Fig. 5b). These results suggest that IFN‐γ suppresses Th17 cell differentiation in vitro. To elucidate whether γδT cells play a direct role in Th17 cell differentiation in vitro, we used pulmonary γδT cells derived from WT and IFN‐γ–/– mice. After co‐culture with CD4+ T cells and γδT cells derived from WT mice, the proportion of IL‐17A+ CD4+ T cells was significantly lower than γδT cells derived from IFN‐γ–/– mice (Fig. 5c). To confirm further the direct effects of IFN‐γ from γδT cells, we used CD4+ T cells from IFN‐γ–/– mice. As shown in Fig. 5d, γδT cells derived from WT mice suppressed IL‐17+ CD4+ T cells, whereas γδT cells derived from IFN‐γ–/– mice did not. Taken together, the results showed that γδT cells seem to suppress Th17 cell differentiation via IFN‐γ production.

Figure 5.

Effects of interferon (IFN)‐γ+ γδT cells in T helper 17 (Th17) cell differentiation in vitro. (a) Splenic CD4+ T cells were isolated from wild‐type (WT) and T cell receptor (TCR)δ–/– mice and cultured in Th0 conditions [anti‐CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb), anti‐CD28 mAb, anti‐interferon (IFN)‐γ mAb and anti‐interleukin (IL)‐4 mAb], Th17 conditions (anti‐CD3 mAb, anti‐CD28 mAb, transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β, IL‐6, anti‐IFN‐γ mAb and anti‐IL‐4 mAb) for 96 h, as described in Materials and methods. Cells were stained for CD3ε, CD4, IFN‐γ, IL‐17A and analysed by flow cytometry. CD4+CD3ε+ cells were gated. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). *P < 0·05. (b) Splenic CD4+ T cells from WT mice were cultured in Th17 conditions (anti‐CD3 mAb, anti‐CD28 mAb, TGF‐β, IL‐6 and anti‐IL‐4 mAb) with/without anti‐IFN‐γ mAb for 96 h, as described in Materials and methods. Cells were stained for CD3ε, CD4, IFN‐γ, IL‐17A and analysed by flow cytometry. CD4+CD3ε+ cells were gated. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05. (c,d) Pulmonary γδT cells were harvested from WT and IFN‐γ–/– mice and purified, as described in Materials and methods. The purified pulmonary γδT cells were expanded by IL‐2, IL‐7 and IL‐15 for 12 days. Splenic CD4+ T cells from WT and IFN‐γ–/– mice were co‐cultured with the expanded γδT cells derived from WT and IFN‐γ–/– mice under Th17 conditions (anti‐CD3 mAb, anti‐CD28 mAb, TGF‐β, IL‐6 and anti‐IL‐4 mAb) for 96 h, as described in Materials and methods. Cells were stained for CD3ε, CD4, IFN‐γ, IL‐17A and analysed by flow cytometry. CD4+CD3ε+ cells were gated. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05.

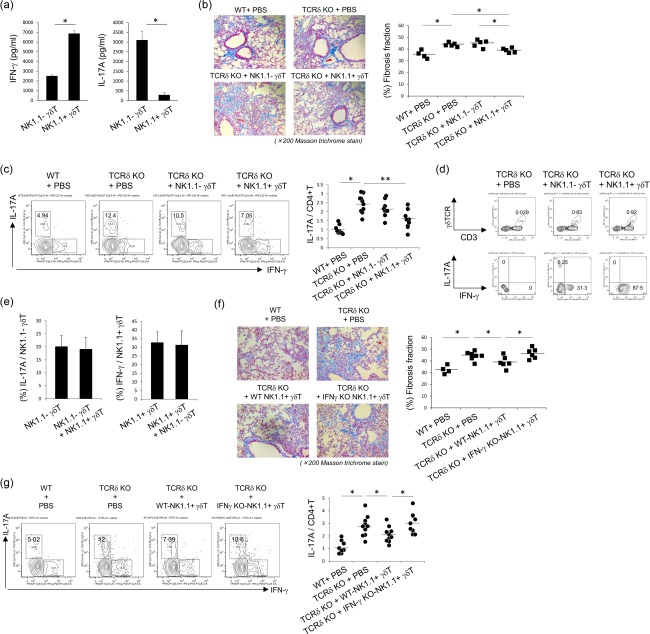

IFN‐γ+ γδT cells attenuate bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis

To examine the effects of IFN‐γ from γδT cells in the progression of pulmonary fibrosis, γδT cells were separated into two subsets based on the expression of NK1·1. As shown in Fig. 6a, NK1·1+ γδT cells showed large amounts of IFN‐γ production compared with NK1·1– γδΤ cells. In TCRδ–/– mice, NK1·1+ γδT cells reduced collagen accumulation and fibrosis fraction in the lungs, whereas NK1.1– γδT cells did not (Fig. 6b). The transfer of NK1·1+ γδT cells in TCRδ–/– mice reduced pulmonary IL‐17A+CD4+ T cells (Fig. 6c). After NK1·1+ γδT cells transferred into TCRδ–/– mice, pulmonary γδT cells showed large amounts of IFN‐γ production in vivo (Fig. 6d). To examine the interactions for cytokine production in γδT cell subsets, NK1·1– γδT cells and NK1·1+ γδT cells were co‐cultured in vitro. IFN‐γ production from NK1·1+ γδT cells and IL‐17A production from NK1·1– γδT cells were not significantly different in the presence or absence of other γδT cell subsets (Fig. 6e).

Figure 6.

Inhibitory effects of interferon (IFN)‐γ+ γδT cells in the progression of pulmonary fibrosis. (a) Pulmonary natural killer (NK)1·1– γδT and NK1·1+ γδT cells were purified from wild‐type (WT) mice and expanded by interleukin (IL)−2, IL‐7 and IL‐15 for 12 days as described in Materials and methods. The expanded γδT cells were stimulated by anti‐CD3 and anti‐CD28 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for 72 h. IFN‐γ and IL‐17A in the culture supernatant were measured by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Data are mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). *P < 0·05. (b) The expanded NK1·1– γδT and NK1·1+ γδT cells from WT mice were transferred into T cell receptor (TCR)δ–/– mice (1 × 105 cells/mice). Four WT mice received phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), five TCRδ–/– mice received PBS, five TCRδ–/– mice received NK1.1– γδT cells and five TCRδ–/– mice received NK1·1+ γδT cells. The lung tissues were removed on day 21 after bleomycin exposure. Paraffin sections were stained with Masson's trichrome. Original magnification was ×200. Fibrosis fraction was measured by quantitative image analysis, as described in Materials and methods. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05. (c) At 18 days after bleomycin exposure, pulmonary lymphocytes were harvested and then stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)/ionomycin for 6 h. Cells were stained for CD3ε, CD4, IFN‐γ, IL‐17A and analysed by flow cytometry. CD4+CD3ε+ cells were gated. Data are shown as a ratio of IL‐17A+ cells in CD4+ T cells compared with those in control mice. The value of control mice was shown by mean of two independent experiments as 1·0. Graph represents values of two independent mice, using the average of the control mice. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01. (d) The expanded NK1·1– γδT and NK1·1+ γδT cells from WT mice were transferred into TCRδ–/– mice (2 × 106 cells/mice). At 3 days after bleomycin exposure, pulmonary lymphocytes were harvested and then stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 6 hrs. Cells were stained for CD3ε, TCRδ, IFN‐γ, IL‐17A and analysed by flow cytometry. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. (e) The expanded NK1·1– γδT (5 × 105 cells/ml) and NK1·1+ γδT cells (5 × 105 cells/ml) were co‐cultured with anti‐CD3 mAb and anti‐CD28 mAb for 96 h. IFN‐γ and IL‐17A from NK1·1– or NK1·1+ fractions were analysed by flow cytometry. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. (f) Pulmonary NK1·1+ γδT cells were purified from WT and IFN‐γ–/– mice and expanded by IL‐2, IL‐7 and IL‐15 for 12 days, as described in Materials and methods. Then, the expanded γδT cells were transferred into TCRδ–/– mice (1 × 105 cells/mice). Four WT mice received PBS, seven TCRδ–/– mice received PBS, six TCRδ–/– mice received NK1·1+ γδT cells from WT mice and six TCRδ–/– mice received NK1·1+ γδT cells from IFN‐γ–/– mice. The lung tissues were removed on day 21 after bleomycin exposure. Paraffin sections were stained with Masson's trichrome. Original magnification was ×200. Fibrosis fraction was measured by quantitative image analysis, as described in Materials and methods. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05. (g) At 18 days after bleomycin exposure, pulmonary lymphocytes were harvested and then stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 6 h. Cells were stained for CD3ε, CD4, IFN‐γ, IL‐17A and analysed by flow cytometry. CD4+CD3ε+ cells were gated. Data are shown as a ratio of IL‐17A+ cells in CD4+ T cells, compared with those in control mice. The value of control mice was shown by mean of two independent experiments as 1·0. Graph represents each values of two independent mice, using the average of the control mice. Data are mean ± s.d. *P < 0·05.

Furthermore, to confirm the role of IFN‐γ+ γδT cells in bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis, NK1·1+ γδT cells from WT and IFN‐γ–/– mice were transferred into bleomycin‐treated TCRδ–/– mice. The results showed that NK1·1+ γδT cells from WT mice reduced collagen accumulation and fibrosis fraction in the lungs, whereas NK1·1+ γδT cells from IFN‐γ–/– mice did not (Fig. 6f). In TCRδ–/– mice receiving NK1·1+ γδT cells from IFN‐γ–/– mice, pulmonary IL‐17A+CD4+ T cells were not reduced (Fig. 6g).

Discussion

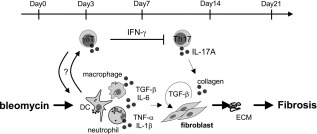

In this study, we demonstrated that γδT cells play a regulatory role in the development of bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis. In TCRδ–/– mice, the severity of pulmonary fibrosis correlated with accumulation of IL‐17A+ CD4+ T cells in lung tissues. Infusion of γδT cells in TCRδ–/– mice attenuated pulmonary fibrosis and decreased pulmonary IL‐17A+ CD4+ T cells significantly compared with control mice. After exposure to bleomycin, pulmonary γδT cells secreted large amounts of IFN‐γ in WT mice. The results also showed suppression of Th17 cell differentiation in the presence of IFN‐γ+ γδT cells in vitro. Collectively, these results suggest that IFN‐γ+ γδT cells seem to suppress IL‐17+CD4+ T cells responses in bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis (summarized schematically in Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the role of γδT cells in pulmonary fibrosis. Schematic diagram illustrating the role of γδT cells in the suppression of pulmonary fibrosis. After bleomycin exposure, γδT cells expanded or accumulated into lung tissues. These cells reduced pulmonary interleukin (IL)−17A+ CD4+ T cells and played regulatory roles in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis.

The presence of γδT cells is critical for a controlled immune response in the lung. In various lung diseases, γδT cells play an effective or suppressive role by secreting various cytokines such as IFN‐γ, IL‐17A, IL‐22 and IL‐4 5, 6, 10. In the pathogenesis of bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis, it was reported that IL‐17A+ γδT and CXCL10+ γδT cells involved as the inflammatory or inhibitory agents, respectively 5, 11, 21. Conversely, we focused previously on IFN‐γ‐producing γδT cells and reported that these cells might participate in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis in systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients 24. In the present study, we showed an accumulation of IFN‐γ+ γδT cells and IL‐17A+ γδT cells in lung tissues after bleomycin exposure. It is reported that IFN‐γ has anti‐fibrotic properties while IL‐17A has profibrotic effects, both in vivo and in vitro 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21. Based on these reports, γδT cells seem to have opposite effects in the progression of bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis. Conversely, we showed that pulmonary fibrosis was exacerbated in TCRδ–/– mice, suggesting that γδT cells might function as a regulatory T cells against bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis. We speculate that γδT cells suppress bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis through three potential mechanisms: uncontrollability of Th17 cells, over‐expression of TGF‐β and reduction of Tregs. These scenarios are discussed below.

First, does uncontrollability of IL‐17A‐producing CD4+ T cells play a role? IL‐17A had been implicated in the regulation of bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis via collagen and TGF‐β production from fibroblasts 21. In this study, we found a higher proportion of pulmonary IL‐17A+ CD4+ T cells in TCRδ–/– mice compared with WT mice. Furthermore, using IL‐17A–/–TCRδ–/– mice, we found that IL‐17A played a pivotal role in the development of pulmonary fibrosis in TCRδ–/– mice. In humans and mice, IL‐17A+CD4+αβTCR+ (Th17) cells are the major source of IL‐17A 26. Previous studies showed that Th17 cells exacerbated pulmonary fibrosis in bleomycin‐induced IP mice 20, 21. Blocking the recruitment of CD3+ or CD4+ T cells resulted in fewer fibrotic lesions 27, 28. These findings supported that bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis was dependent upon T cells and the absence of αβT cells might attenuate fibrosis. In TCRδ–/– mice treated with bleomycin, uncontrolled Th17 cells might lead to exacerbation of pulmonary fibrosis. Infusion of γδT cells into TCRδ–/– mice treated with bleomycin reduced the percentage of lung fibrosis and collagen accumulation and lowered the percentage of pulmonary IL‐17A+CD4+ T cells compared with control mice. These findings suggest that γδT cells seem to suppress the activity of pulmonary Th17 cells and attenuate the development of fibrosis. However, several studies reported that γδT cells induced the generation and activation of Th17 cells 29, 30. Do et al. 31 also reported that CCR6+ γδT cells play a crucial role in enhancing in‐vivo Th17 cell differentiation and exacerbation of T cell‐mediated colitis. Conversely, there is information on whether γδT cells suppress Th17 cell differentiation. To explore the inhibitory mechanisms of γδT cells, we evaluated Th17 cell differentiation in vitro. The results showed that γδT cells derived from WT mice suppressed Th17 cell differentiation in vitro, whereas γδT cells derived from IFN‐γ–/– mice did not. Thus, γδT cells might suppress Th17 cell differentiation depending on IFN‐γ production. IFN‐γ is known as one of the Th1 cytokines and could suppress Th17 cell differentiation both in vivo and in vitro 32, 33.

The current study shows that γδT cells can be classified into two major subsets based on distinct cytokine profiles, IFN‐γ‐producing γδT cells and IL‐17A‐producing γδT cells. The expression of NK1·1 and CD27 versus Scart‐2 and CCR6 segregate with the commitment of γδT cells to produce IFN‐γ and IL‐17A, respectively 12, 34, 35, 36. In the present study, we also indicated that NK1·1+ γδT cells showed large amounts of IFN‐γ production and were attenuated by bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis through the suppression of pulmonary Th17 cell activities. However, NK1·1+ γδT cells derived from IFN‐γ–/– mice did not attenuate the progression of lung fibrosis. Following exposure to bleomycin, we showed an increase in pulmonary IFN‐γ+γδT cells in WT mice. Previously, Haas et al. 35 and our group 8 showed that γδT cells can produce large amounts of IFN‐γ in response to various stimuli, such as TCR, IL‐12 and IL‐18. Bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis is characterized by over‐expression of IL‐12 and IL‐18 in lung tissues 37, 38. Therefore, IFN‐γ seems to be induced by pulmonary γδT cells through IL‐12 or IL‐18 and it seems to suppress the pulmonary Th17 cells response in bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis.

Secondly, does excess production of fibrotic factors play a role in exacerbation of pulmonary fibrosis in TCRδ–/– mice? TGF‐β is known as one of major profibrotic factors in vivo and in vitro 39. After bleomycin exposure, the expression of pulmonary TGF‐β mRNA and collagen production increased in TCRδ–/– mice compared with WT mice. Previous reports showed that TGF‐β induced fibroblast proliferation and collagen production in bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis 40. Conversely, inhibition of TGF‐β signalling by TGF‐β neutralizing antibodies or TGF‐β receptor blockers attenuated bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis 41, 42. Furthermore, Wilson et al. 21 reported that the profibrotic activity of TGF‐β in the development of pulmonary fibrosis may be attributed to the induction of IL‐17A from T cells. In TCRδ–/– mice treated with bleomycin, the increase in pulmonary IL‐17A+ CD4+ T cells could be one possible reason for the excessive production of TGF‐β. Consequently, over‐expression of TGF‐β might induce collagen synthesis and cause exacerbation of pulmonary fibrosis in TCRδ–/– mice.

After bleomycin exposure, myeloid cells infiltrated into the BALF by several chemokines and exacerbated pulmonary fibrosis 43. It was reported that γδT cells also produced chemokines such as CCL3, CCL5 and CXCL10 in several stimuli 11, 44, 45, 46. In the present study, we showed that γδT cells might induce the infiltration of dendritic cells and neutrophils into the BALF. However, the transfer of γδT cells in TCRδ–/– mice attenuated bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis. Thus, these results demonstrated that severe cell infiltrations in BALF did not cause the enhanced severity of fibrosis observed in TCRδ–/– mice.

Thirdly, is insufficiency of regulatory T cells relative to Th17 cells important? In the present study, we showed that the proportion of pulmonary FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells was not significantly different between WT and TCRδ–/– mice after bleomycin exposure. FoxP3+CD4+ T cells are Tregs and can suppress Th17 cell responses 47. In peripheral tissues, the expression of FoxP3 in CD4+ T cells was induced in the presence of TGF‐β 48. However, pulmonary FoxP3+CD4+ T cells were not increased in TCRδ–/– mice, even under the condition of TGF‐β over‐expression. Our findings demonstrated that FoxP3+CD4+ T cells did not play a role in the increase of Th17 cells in TCRδ–/– mice. Thus, the regulatory role of γδT cells in the development of pulmonary fibrosis seem to be involved directly in the suppression of IL‐17A production by CD4+ T cells.

In conclusion, our results demonstrated that γδT cells attenuated bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis. The regulatory role of γδT cells in pulmonary fibrosis seems to be mediated through the suppression of IL‐17A+CD4+ T cell activity via IFN‐γ production. These findings should enhance our understanding of the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis and that targeting γδT cells is a potentially useful therapeutic strategy in the management of pulmonary fibrosis.

Disclosure

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Y. Iwakura for providing IL‐17A–/– mice. We also thank Dr F. G. Issa for the critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Research Program for Intractable Diseases, Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

References

- 1. Khalil N, O'Connor R. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: current understanding of the pathogenesis and the status of treatment. Can Med Assoc J 2004; 171:153–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. King TE Jr. Clinical advances in the diagnosis and therapy of the interstitial lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 172:268–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Luna MA, Bedrossian CW, Lichtiger B, Salem PA. Interstitial pneumonitis associated with bleomycin therapy. Am J Clin Pathol 1972; 58:501–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Izbicki G, Segel MJ, Christensen TG, Conner MW, Breuer R. Time course of bleomycin‐induced lung fibrosis. Int J Exp Pathol 2002; 83:111–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Braun RK, Ferrick C, Neubauer P et al IL‐17 producing gammadelta T cells are required for a controlled inflammatory response after bleomycin‐induced lung injury. Inflammation 2008; 31:167–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simonian PL, Wehrmann F, Roark CL, Born WK, O'Brien RL, Fontenot AP. γδT cells protect against lung fibrosis via IL‐22. J Exp Med 2010; 207:2239–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Simonian PL, Roark CL, Diaz del Valle F et al Regulatory role of γδ T cells in the recruitment of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to lung and subsequent pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol 2006; 177:4436–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Segawa S, Goto D, Yoshiga Y et al Involvement of NK 1.1‐positive γδT cells in interleukin‐18 plus interleukin‐2‐induced interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2011; 45:659–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lo Re S, Dumoutier L, Couillin I et al IL‐17A‐producing gammadelta T and Th17 lymphocytes mediate lung inflammation but not fibrosis in experimental silicosis. J Immunol 2010; 184:6367–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Born WK, Lahn M, Takeda K, Kanehiro A, O'Brian RL, Gelfand EW. Role of γδT cells in protecting normal airway function. Respir Res 2000; 1:151–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pociask DA, Chen K, Choi SM, Oury TD, Steele C, Kolls JK. γδT cells attenuate bleomycin‐induced fibrosis through the production of CXCL10. Am J Pathol 2011; 178:1167–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Korn T, Petermann F. Development and function of interleukin 17‐producing γδ T cells. Ann NY Acad Sci 2012; 1247:34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Duncan MR, Berman B. Gamma interferon is the lymphokine and beta interferon the monokine responsible for inhibition of fibroblast collagen production and late but not early fibroblast proliferation. J Exp Med 1985; 162:516–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gillery P, Serpier H, Polette M et al Gamma‐interferon inhibits extracellular matrix synthesis and remodeling in collagen lattice cultures of normal and scleroderma skin fibroblasts. Eur J Cell Biol 1992; 57:244–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yuan W, Yufit T, Li L, Mori Y, Chen SJ, Varga J. Negative modulation of alpha1(I) procollagen gene expression in human skin fibroblasts: transcriptional inhibition by interferon‐gamma. J Cell Physiol 1999; 179:97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kimura T, Ishii Y, Morishima Y et al Treatment with α‐galactosylceramide attenuates the development of bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol 2004; 172:5782–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim JH, Kim HY, Kim S, Chung JH, Park WS, Chung DH. Natural killer T (NKT) cells attenuate bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis by producing interferon‐γ. Am J Pathol 2005; 167:1231–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Keane MP, Belperio JA, Burdick MD, Strieter RM. IL‐12 attenuates bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2001; 281:L92–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wynn TA. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol 2008; 214:199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sonnenberg GF, Nair MG, Kirn TJ, Zaph C, Fouser LA, Artis D. Pathological versus protective functions of IL‐22 in airway inflammation are regulated by IL‐17A. J Exp Med 2010; 207:1293–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wilson MS, Madala SK, Ramalingam TR et al Bleomycin and IL‐1b‐mediated pulmonary fibrosis is IL‐17A dependent. J Exp Med 2010; 207:535–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holcombe RF, Baethge BA, Wolf RE, Betzing KW, Stewart RM. Natural killer cells and gamma delta T cells in scleroderma: relationship to disease duration and anti‐Scl‐70 antibodies. Ann Rheum Dis 1995; 54:69–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bendersky A, Markovits N, Bank I. Vgamma9+ gammadelta T cells in systemic sclerosis patients are numerically and functionally preserved and induce fibroblast apoptosis. Immunobiology 2010; 215:380–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Segawa S, Goto D, Horikoshi M et al Involvement of CD161+ Vδ1+ γδT cells in systemic sclerosis: association with interstitial pneumonia. Rheumatology (Oxf) 2014; 53:2259–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Itohara S, Mombaerts P, Lafaille J et al cell receptor δ gene mutant mice: independent generation of γδT cells and programmed rearrangements of γδ TCR gene. Cell 1993; 72:337–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bluestone JA, Mackay CR, O'Shea JJ, Stockinger B. The functional plasticity of T cell subsets. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9:811–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sharma SK, MacLean JA, Pinto C, Kradin RL. The effect of an anti‐CD3 monoclonal antibody on bleomycin‐induced lymphokine production and lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 154:193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Westermann W, Schöbl R, Rieber EP, Frank KH. Th2 cells as effectors in postirradiation pulmonary damage preceding fibrosis in the rat. Int J J Radiat Biol 1999; 75:629–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sutton CE, Lalor SJ, Sweeney CM, Brereton CF, Lavelle EC, Mills KH. Interleukin‐1 and IL‐23 induce innate IL‐17 production from γδT Cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity 2009; 31:331–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cui Y, Shao H, Lan C et al Major role of γδT cells in the generation of IL‐17+ uveitogenic T cells. J Immunol 2009; 183:560–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Do JS, Visperas A, Dong C, Baldwin WM III, Min B. Cutting edge: generation of colitogenic Th17 CD4 T cells is enhanced by IL‐17+ γδT cells. J Immunol 2011; 186:4546–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tanaka K, Ichiyama K, Hashimoto M et al Loss of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 in helper T cells leads to defective Th17 differentiation by enhancing antagonistic effects of IFN‐γ on STAT3 and Smads. J Immunol 2008; 180:3746–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chu CQ, Swart D, Alcorn D, Tocker J, Elkon KB. Interferon‐γ regulates susceptibility to collagen‐induced arthritis through suppression of interleukin‐17. Arthritis Rheum 2007; 56:1145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kisielow JM, Kopf Karjalainen K. SCART scavenger receptors identify a novel subset of adult gammadelta T cells. J. Immunol 2008; 181:1710–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Haas JD, González FH, Schmitz S et al CCR6 and NK1.1 distinguish between IL‐17A and IFN‐gamma‐producing gammadelta effector T cells. Eur J Immunol 2009; 39:3488–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ribot JC, deBarros A, Pang DJ et al CD27 is a thymic determinant of the balance between interferon‐gamma‐ and interleukin 17‐producing gammadelta T cell subsets. Nat Immunol 2009; 10:427–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kaneko Y, Kuwano K, Hagimoto N et al Expression of B7‐1, B7‐2, and interleukin 12 in bleomycin‐induced pneumopathy in mice. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 1998; 116:306–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hoshino T, Okamoto M, Sakazaki Y, Kato S, Young HA, Aizawa H. Role of proinflammatory cytokines IL‐18 and IL‐1beta in bleomycin‐induced lung injury in humans and mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009; 41:661–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gu YS, Kong J, Cheema GS, Keen CL, Wick G, Gershwin ME. The immunobiology of systemic sclerosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2008; 38:132–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhao J, Shi W, Wang YL et al Smad3 deficiency attenuates bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002; 282:585–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Giri SN, Hyde DM, Hollinger MA. Effect of antibody to transforming growth factor beta on bleomycin induced accumulation of lung collagen in mice. Thorax 1993; 48:959–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Higashiyama H, Yoshimoto D, Kaise T et al Inhibition of activin receptor‐like kinase 5 attenuates bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis. Exp Mol Pathol 2007; 83:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moeller A, Ask K, Warburton D, Gauldie J, Kolb M. The bleomycin animal model: a useful tool to investigate treatment options for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2008; 40:362–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tagawa T, Nishimura H, Yajima T et al Vdelta1+ gammadelta T cells producing CC chemokines may bridge a gap between neutrophils and macrophages in innate immunity during Escherichia coli infection in mice. J Immunol 2004; 173:5156–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pennington DJ, Silva‐Santos B, Hayday AC. Gammadelta T cell development – having the strength to get there. Curr Opin Immunol 2005; 17:108–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Macleod AS, Havran WL. Functions of skin‐resident γδ T cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 2011; 68:2399–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu Rev Immunol 2012; 30:531–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N et al Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25– naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF‐beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med 2003; 198:1875–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]