Abstract

Faith-based interventions show promise for reducing health disparities among ethnic minority populations. However, churches vary significantly in their readiness and willingness to support these programs. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with priests, other church leaders, and lay health advisors in churches implementing a physical activity intervention targeting Latinas. Implementation effectiveness was operationalized as average 6-month participation rates in physical activity classes at each church. Factors facilitating implementation include church leader support and strength of parishioners' connection to the church. Accounting for these church level factors may be critical in determining church readiness to participate in health promotion activities.

Keywords: Program implementation, physical activity, faith-based, Latinas

Introduction

Latinos, who are the largest and fastest growing ethnic minority group in the U.S.,1 are more likely to be overweight or obese compared to Non-Hispanic White women. Data from the 2011-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey indicate that 77% of Hispanic/Latino women are overweight or obese (BMI≥25) compared to 63% of Non-Hispanic White women.2 This disparity in weight status may be partially attributed to lower engagement in regular leisure time physical activity among Latinas. 3,4

Faith-based communities, particularly Catholic churches, have been identified as a promising setting for reaching Latinos who are under-represented in health promotion efforts.5 According to The Pew Research Center, 68% of Latinos identify themselves as Catholic and almost 42% of Latino Catholics report attending church at least once a week. 6 Preliminary evidence suggests that faith-based health promotion programs can positively affect health behaviors such as physical activity among Latinos.7-10 However, faith communities may vary significantly in their motivation and/or capacity to serve as conduits for these programs. 11,12 To date, there has been a lack of research examining the impact of faith based interventions on the health practices of community members or factors that facilitate program implementation.13

Currently, the extent to which church-specific factors such as church leader support and physical capacity influence implementation effectiveness is unknown.14 The current study contributes to the literature by applying an organizational framework of innovation implementation15-19 to identify church-specific factors affecting implementation of a multilevel faith-based physical activity program for Latina women (Faith in Action/Fe en Acción).

Faith in Action (Fe en Acción)

Faith in Action is a six-year randomized community controlled trial designed to examine the efficacy of a multi-level intervention aimed to increase physical activity among church-going Latina women. Consistent with the Social Ecological Model, 20 Faith in Action targets individual-level (e.g., physical activity and beliefs), intrapersonal-level (e.g., social support), organizational (e.g., access to rooms), and environmental-level influences on physical activity (e.g., increasing access to safe parks). The program did not train the clergy to implement program activities. Program activities are implemented through promotoras or lay health advisors as they have been found to be effective agents of change. 21 All participating churches signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the university partner. The MOU committed the university partner to provide training to promotoras, collect data at the parish, provide incentives to participants, provide summary of findings to church leaders, and provide workshops to leaders about sustainability. In turn, the churches committed to identify the promotoras, provide physical space, and support recruitment.

A total of 16 Catholic churches agreed to participate in Faith in Action. Churches were stratified by size and location prior to randomization to either the physical activity intervention or an attention-control condition (cancer control and prevention). To alleviate staffing burdens associated with the physical distance between churches (>60 miles), a staggered implementation approach was used;22 however, intervention activities did not vary across churches.

Briefly, parishioners at churches in the physical activity intervention were invited to participate in physical activity classes offered six times a week either in their churches or at local parks. Class offerings included walking groups, cardio dance, and strength training, in response to participants' varying levels of fitness at the start of the program. Classes were taught by trained promotoras and included a warm-up, moderate-to-vigorous exercise class, and cool-down. Each class began with prayer and ended with a discussion of one of fourteen prepared health information sheets, including healthy eating, injury prevention, the benefits of physical activity, and the importance of drinking water.23,24 Participants also received five 30-minute motivational interviewing (MI) calls over the course of the two-year intervention. MI is a client-centered counseling technique that uses persuasive messaging to encourage participants to develop their own motivation to change.25 Key techniques include listening reflectively and working with clients to develop self-motivational statements tailored to that individual's readiness to change and level of self-efficacy 26. Consistent with an approach used by Eat for Life, a multi-component intervention developed to increase fruit and vegetable consumption among African-Americans in black churches, 27 MI sessions in Faith in Action were used to address barriers to physical activity and reinforce activity efforts.

Active recruitment of participants at each church occurred via fliers, word of mouth, and announcements in the church bulletins and during Spanish church services. Promotoras were specifically hired and received six weeks of training for the purpose of teaching the physical activity programs offered at the intervention churches. The promotoras were all bilingual women engaged in an active lifestyle. With one exception, all promotoras were also members of their respective church. In the exception case, a promotora was hired from outside the church only after unsuccessful attempts to find a suitable candidate from within the church.

An Organizational Framework of Innovation Implementation

This study is guided by the Complex Innovation Implementation framework (CII), an organizational model of innovation implementation that has been used extensively in the health care and manufacturing sectors. 15-19 The CII was developed to examine innovation implementation in situations where (a) successful implementation is contingent on participation of multiple members of the organization, and (b) organizational members cannot choose to adopt or otherwise participate in the “innovation” (i.e., new policies, programs, or practices) until permission is granted from a higher level of authority. 28 Briefly, the CII posits that implementation effectiveness is affected by leadership support, resource availability, and innovation-values fit (i.e., the extent to which the intervention being implemented fits with church values). Implementation processes, defined as the specific policies, practices, and strategies used to put an intervention in place and support its use, are also hypothesized to play a major role. 15

Methods

Study Design and Sample

Design details about the randomized controlled trial have been published elsewhere. 29 To examine church-specific factors affecting implementation, a multiple case study design was used 30, with churches as the unit of analysis. Case studies are well-suited for studying non-linear, context-sensitive processes such as implementation 31, and permit in-depth analysis of individual cases as well as systematic cross-case comparison. Five of eight churches in the physical activity intervention were invited to participate in this study; the remaining three churches were excluded because they had not yet begun implementing the intervention. Participating churches did not differ significantly from those excluded, except in the number of masses offered in Spanish, which was slightly higher at excluded churches. To protect confidentiality, participating churches will be referred to throughout this study as churches A-E. Information on church characteristics such as membership size and estimated percentage of Latino members is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of Participating Churches (n=5).

| Church A | Church B | Church C | Church D | Church E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total membership | 1300 | 4667 | 2000 | 4000 | 650 |

| Latino membership (estimated %) | 30% | 65% | 50% | Not reported | 70% |

| # Spanish-language services offered each weekend | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Length of Key Informants' Association with Church | 14 | 10 | 6 | 15 | 13 |

Data and Variables

Three key stakeholders at each participating church were invited to participate in semi-structured interviews: the senior priest, one promotora, and another church leader or staff member with whom Faith in Action project staff had the most contact (e.g., deacon or church secretary). Of the 15 key stakeholders invited, 14 agreed to participate. With the exception of the clergy, all interviewees were women. The majority of respondents were of Latino descent (71%; n=10 of 14), and had been associated with their respective church for an average of 10 years (range of 3 to 14 years). Almost all respondents (93%; n=13 of 14) indicated they could speak Spanish.

Interviews were conducted between August 2012 and February 2013 in English by a single interviewer who did not have a previous relationship with the interview participants or with Faith in Action intervention activities. Interviews consisted of a series of closed- and open-ended questions informed by the CII framework and tailored to participant role (i.e., priest, other church leader or staff, promotora); this approach allowed us to maintain consistency across respondents, while remaining sufficiently open-ended for respondents to elaborate on issues they considered important or relevant.32 Interviews lasted an average length of 20 minutes, and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. To encourage open disclosure, confidentiality was assured. Participants received a ten dollar cash incentive upon completion of the interview.

Data on implementation effectiveness (i.e., consistency and quality of intervention use) were also collected for each church. In the current study, implementation effectiveness was operationalized as the average participation rates in physical activity classes by enrolled participants during the first six months of implementation. The study was reviewed for human subjects protection and approved by the Institutional Review Board at San Diego State University.

Data Analysis

First, the qualitative software program NVivo 9 33 was used to code all qualitative data files. The initial codebook was informed by the CII, but was subsequently refined to include emergent constructs identified in the data 34. In refining the codebook, the first author and second author each independently coded approximately half of the transcripts, compared coding, and reconciled disagreements until consensus was reached. The first author then independently coded the remaining interview transcripts. Once all transcripts were coded, a within-case analysis of facilitators and barriers to implementation was conducted for each church. Reports were generated for all text segments associated with each code, and assessed for the degree to which the code emerged in the data (“strength”, assessed as low, medium, and high). 35 An overview of identified constructs, their operational definitions, and coding decision rules is provided in Table 2. The coding manual contained eight codes developed both inductively from the conceptual framework and deductively from the data. Previous literature suggests that mean participation rates in family-based prevention and control programs typically range from 59% to 85% and are an important predictor of subsequent changes in program outcomes such as physical activity and BMI. 36-39 Consistent with this literature, a cut-point of approximately 65% was set for differentiating between churches with high vs. low average participation rates. Finally, qualitative data were compared to quantitative assessments of implementation effectiveness to identify church-specific factors most salient to implementation of Faith in Action (see Tables 3 and 4).

Table 2. Coding Manual.

| Construct | Operational definition | Decision rules for “low” | Decision rules for “medium” | Decision rules for “high” |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational readiness for change | Priest and church staff 1. Report having other programs (health related or not) and 2. Leadership to support a program. | Reports neither of the two criteria. | Reports one of the two criteria. | Reports both criteria. |

| Priest support (*management support) | The priest 1. Makes mass announcements and/or other verbal communication regarding Faith in Action 2. Shows enthusiasm, and 3. Demonstrates knowledge of the program. | Priest does not fulfill any of these criteria. | Priest fulfills one or two of these criteria. | Priest fulfills all three criteria. |

| Staff support (*management support) | Staff member has 1.Verbal communications with parishioners about Faith in Action, 2. Places announcements in the bulletin, and 3. Helps with the arrangement and scheduling of rooms. | Staff member does not fulfill any of these criteria. | Staff member fulfills one or two of these criteria. | Staff member fulfills all three criteria. |

| Resource availability | Church leaders report having 1. Space to conduct the exercise classes at the church and 2. Time to promote the program. | Report neither space nor time. | Report one of these criteria. | Reports both criteria. |

| Innovation fit with users' values | Church leaders report 1. Faith in Action coincides with the mission and values of the church, 2. The church should play a role in health promotion, and 3. The priest supports that his health affects his ability to lead the parish. | Does not fulfill any of these criteria. | Fulfills one or two of these criteria. | Fulfills all three criteria. |

| Implementation climate | Church leaders make Faith in Action a priority in the church by 1. Providing access to rooms for exercise classes, 2. Making announcements in bulletin or at weekly services, and 3. Communicating knowledge about Faith in Action to parishioners. | Does not fulfill any of these criteria. | Fulfills one or two of these criteria. | Fulfills all three criteria. |

| Implementation policies and practices | Church leaders ensure access to space/rooms for exercise classes. | Does not fulfill criteria. | Somewhat fulfills criteria. | Fulfills criteria. |

| Parishioner engagement | Church leaders' perceptions of 1. Parishioner's interest in the program, 2. Importance of exercise to parishioners, and 3. Issues around getting parishioners to participate | Low ratings on the first two criteria and expressed many issues around participation. | Medium ratings on the first two criteria and not many issues around getting parishioners to participate. | High ratings on the first two criteria and no issues around getting parishioners to participate. |

Note: Management support was given an overall rating by averaging the priest's and staff member's rating.

Table 3. Average participation rates in physical activity classes at each church.

| Church | Date of first physical activity class | Number of participants enrolled | Average participation rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 09/06/11 | 17 | 41% |

| B | 01/09/12 | 35 | 74% |

| C | 03/22/12 | 25 | 84% |

| D | 06/19/12 | 28 | 75% |

| E | 08/21/12 | 29 | 34% |

Enrollment and participation rates calculated 6 months after the program began at each church

Table 4. Church-specific factors affecting implementation of Faith in Action.

| Priest Support | Church staff support | Innovation-values fit | Resource availability | Parishioner engagement | Outcome: Implementation effectiveness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Church A | Low | Low | Low | Medium | Low | Low |

| Church B | High | High | High | Medium | High | High |

| Church C | High | High | Medium | High | Medium | High |

| Church D | Low | High | High | Medium | Medium | High |

| Church E | Medium | Low | Medium | Low | Medium | Low |

See Table 2 for definitions

Results

As shown in Table 3, average 6-month participation rates in physical activity classes at each church ranged from 34% to 84%. Of the five churches participating in this study, two were “low” implementers (<=50% participation rates) and three were “high” implementers (>=70% participation rates). No churches were identified as “medium” implementers (50-70% participation rates).

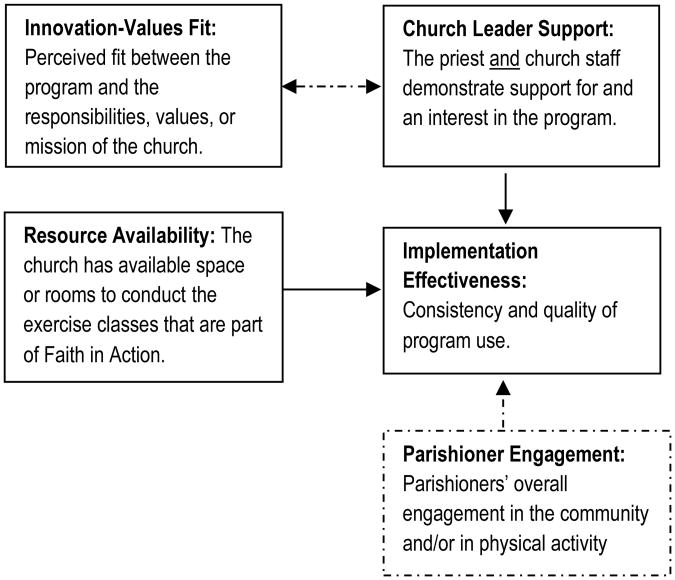

In examining determinants of implementation effectiveness, we found that overall the CII framework fit the data well. Of the four constructs originally hypothesized to affect implementation effectiveness, three constructs – innovation-values fit, leadership support, and resource availability – were identified by participants as affecting implementation. The remaining construct, implementation processes, was dropped from the model because specific strategies used to implement Faith in Action were dictated by project leadership rather than the church, and were therefore not addressed by interview respondents. A new construct, parishioner engagement, emerged as influential and was added to the model. We also found evidence that two of the constructs – innovation-values fit and leadership support – were strongly related and reinforcing. Figure 1 illustrates the relationships among the constructs observed in cross-case comparisons. Each of these results is also examined in more detail below.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework of Factors Affecting Implementation Effectiveness *.

Adapted from the Complex Innovation Implementation framework 17-21; dotted lines indicate emergent constructs or relationships

Innovation-values fit

Innovation-values fit differed significantly across churches. In particular, there was a clear division in the extent to which priests and other church leaders and staff noted that Faith in Action was compatible with the church's mission and priorities. In churches B and C, both priests and other leaders or staff described promoting health and well-being of parishioners through programs like Faith in Action as compatible with church values. As one priest put it:

“You can't just take care of your spiritual side. You have to take care of every part of you… If somebody's coming in hurting physically or emotionally and it's not taken care of, it's difficult to focus. It's difficult to allow God to work with you.”

Similarly, a staff member at another church noted that, “I believe that healthy people are more in-tune spiritually.” In contrast, leaders at churches A and E made it clear that they did not perceive promoting physical activity as a goal of the church. Instead, they noted that such activities were instead the responsibility of “society and family and personal.”

In church D, the priest declined to participate in the interview but was described by other respondents as being very “academic,” “by the book,” and less open to community activities and health promotion programs than his predecessor, who was more of a “missionary style priest.” However, another church leader interviewed at this church described health promotion activities as compatible with church values, indicating that this perception of values-fit was not shared by all leaders at this church.

Leadership support

Priest and other church leaders' perceptions of innovation-values fit were heavily linked to their support for the program. In two churches (church B and C), priests and other church leaders all exhibited high levels of support for Faith in Action. For example, one of the promotoras indicated that the priest at her church was always talking about the program with parishioners: “He will say [to the parishioners], ‘Go dance! They have some programs about health right here!’ and point outside.”

In two of the churches (D and E), priests and other church leaders differed in their level of support for the program. In church D, the priest did not support the program and never talked about the program to parishioners; however, another highly placed church leader noted that the program was a “valuable resource” and “opportunity” for the parishioners and made an effort to mobilize church staff and resources to support it. In contrast, at church E, the priest expressed moderate support for the program but church staff support was low and did not result in concrete action being taken to promote the program within the church.

Finally, in church A, both the priest and church staff exhibited low levels of support. Specifically, the priest was not knowledgeable or enthusiastic about the program and in fact, described it as a potential insurance liability. When prompted to provide more information about this concern, the priest indicated that he knew of a private evangelical school that had recently been sued as a result of offering physical activity programs on-site. The staff member at this church did not echo this concern, but did mention her principal interest in the program was the extent to which it might add to her workload in the church office. The promotora at this church strongly noted the lack of support: “We make an announcement after mass, but we don't have a lot of support… the parish doesn't help a lot;” she also stated she felt the lack of support made it difficult for her to effectively promote the program.

Resource availability

All churches indicated that space and/or scheduling for Faith in Action classes could be difficult. In four of the five churches, the primary constraint was not necessarily the underlying infrastructure at the church but competing demands (e.g., fitting in Faith in Action classes around other events and activities). As one staff member put it, “We're a very active parish. There's something going on all the time, so we try to keep a nice balance of it, especially with events that are coming up.” However, in one of the five churches (church E), actual physical space for the program was limited and the church did not have many resources to help; at this church, the priest mentioned hoping to explore a possible partnership with a nearby recreation center but otherwise being uncertain about options.

Parishioner engagement

Parishioner engagement, i.e., parishioners' engagement in physical activity and/or with the community overall, was not initially identified in the CII but emerged during the interviews as strongly affecting implementation effectiveness. In general, none of the respondents identified parishioner engagement in physical activity as high. Several respondents stated that when it came to exercise, both they and parishioners could get “lazy” or “preoccupied with their job, their work, sometimes their family.” However, respondents at most churches explained that their parishioners were engaged in the community. Church A was the only one where respondents noted that parishioners were less engaged in the community, and had more of an attitude of “Stay at home, don't do it, don't get involved.”

Discussion

This study used an organizational framework to explore factors related to effective implementation of a physical activity program in churches. Consistent with this framework,11 study findings suggest that church leader support, innovation-values fit, and resource availability (e.g., time and space) can affect implementation effectiveness. Parishioner engagement also emerged as meaningful. Specifically, study findings revealed that the two “low” implementing churches (average 6-month participation rates <=50%) had low support from church staff or other church leaders, as well as low to medium innovation-values fit, resource availability, and parishioner engagement. In contrast, the “high” implementing churches reported high church leader support, high innovation-values fit, medium to high resource availability, and medium to high parishioner engagement.

In-depth analyses suggest that church leader support and resource availability may be particularly critical to program success. In general, priest support appeared to be critical to implementation effectiveness. Consistent with these findings40 Baruth, Wilcox, and Saunders found a associations between some pastor support-related variables and participant recruitment, retention, and implementation of study requirement among African American churches. Of the five churches in our sample, Church D was the only “high” implementer church that did not also report high levels of support from the priest. However, while the priest at that church was described as very disengaged, other church leaders as well as the promotora were identified as very supportive of the program. It is possible that the support of these other church leaders – which included a church deacon – compensated for the lack of priest support. While further research is needed, these findings suggest that faith-based programs can succeed as long as it has buy-in and support from at least one senior leader within the church.41

Study findings also suggest that church leaders were more supportive of Faith in Action if they noted that it was compatible with church values. Being able to make the case for why health promotion programs are compatible with church values may therefore be critical to not only adoption but ultimately sustainability of faith-based programs. Differences in priest style and training (e.g., academic vs. missionary orientation) may also influence the best strategies for approaching church leaders. For example, some leaders may be convinced to participate simply as an opportunity to build a sense of community among parishioners, while others may need to be convinced of the connection between physical and spiritual well-being.

Finally, study findings indicate that even when church leaders perceive health promotion as compatible with church values, resource availability in the form of space and time can pose a challenge. Lower income churches may be particularly affected, as their resource constraints may be structural rather than due to competing demands. In these settings, successful implementation may be contingent on creative strategies for getting around these constraints, e.g., by working to develop church-community partnerships or agreements that enable programs to have church support but be delivered in alternative community settings.

Limitations

Several limitations must be taken into consideration when interpreting results of this study. First, participating Catholic Churches were all located in areas with a majority Latino population in a single county; thus, results may not be generalizable to all Catholic churches. Second, while case studies are well-suited for studying context-specific processes, the use of a semi-structured interview format could have introduced social desirability bias. To diminish this threat, interviews were conducted with three participants per church, representing different positions and perspectives. Similar interview questions were asked of each participant allowing for comparison and verification of responses within each church. Finally, due to the wave start nature with which Faith in Action was implemented, length of time spent implementing the program differed at each church and may have affected interview responses. In future studies, it might prove useful to interview each organization at the same point in the intervention, for example two weeks after the first physical activity class begins, for consistency.

Conclusion and Implications

Despite these limitations, this study is the first to examine organization-specific factors affecting implementation of health promotion programs in Catholic churches. Catholic churches are an important setting for reaching Latinos who might otherwise be under-represented in health promotion efforts; thus, a better understanding of the dynamics of the Catholic Church and the influence that key players have on parishioners is critical for tailoring interventions in ways that improve program adoption, implementation effectiveness, and subsequent intervention efficacy.

References

- 1.Pew Research Center. Census 2010: 50 Million Latinos. [Accessed April 30, 2014];2011 Available at: http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/reports/140.pdf.

- 2.Ogden C, Carroll M, Kit B, Flegal K. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. Jama. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He X, Baker D. Differences in leisure-time, household, and work-related physical activity by race, ethnicity, and education. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20(3):259–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall S, Jones D, Ainsworth B, Reis J, Levy S, Macera C. Race/ethnicity, social class, and leisure-time physical inactivity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2007;39(1):44–51. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000239401.16381.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He M, Wilmoth S, Bustos D, Jones T, Leeds J, Yin Z. Latino church leaders' perspectives on childhood obesity prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44(S3S):S232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pew Research Center. Changing Faiths: Latinos and the transformation of American religion. [Accessed September 18, 2012];2007 Available at: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2007/04/25/changing-faiths-latinos-and-the-transformation-of-american-religion/

- 7.Bopp M, Fallon E, Marquez D. A faith-based physical activity intervention for Latinos: Outcomes and lessons. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2011;25(3):168–171. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090413-ARB-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreuter M, Fernandez M, Brown M, et al. Increasing information-seeking about HPV vaccination through community partnerships in African-American and Hispanic communities. Family and Community Health. 2012;35(1) doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3182385d13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monsma S, Smidt C. Faith-based interventions for at-risk Latino youths: A study of outcomes. Politics and Religion. 2013;6(2):317–341. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ickes MJ, Sharma M. A systematic review of physical activity interventions in Hispanic adults. Journal Of Environmental And Public Health. 2012;2012:156435–156435. doi: 10.1155/2012/156435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeMarco M, Weiner BJ, Meade S, et al. Assessing the readiness of black churches to engage in health disparities research. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2011;103(9-10):960–967. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30453-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bopp M, Webb B, Fallon E. Urban-rural differences for health promotion in faith-based organizations. Online Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care. 2012;12(2) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bopp M, Peterson J, Webb B. A comprehensive review of faith-based physical activity interventions. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2012:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bopp M, Baruth M, Peterson JA, Webb BL. Leading their flocks to health? Clergy health and the role of clergy in faith-based health promotion interventions. Family & Community Health. 2013;36(3):182–192 111. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31828e671c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein KJ, Sorra JS. The challenge of innovation implementation. Academy of Management Review. 1996;21:1055–1080. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helfrich C, Weiner BJ, McKinney MM, Minasian L. Determinants of implementation effectiveness: adapting a framework for complex innovations. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(3):279. doi: 10.1177/1077558707299887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiner BJ, Lewis MA, Linnan LA. Using organization theory to understand the determinants of effective implementation of worksite health promotion programs. Health Education Research. 2009;24(2):292–305. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aarons GA, Hurlburt MS, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2011;38:4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiner BJ, Haynes-Maslow L, Kahwati L, Kinsinger L. Implementing the MOVE! weight-management program in the Veterans Health Administration, 2007-2010: A qualitative study. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sallis J, Owen N, Fisher E. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer B, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4th. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayala G, Vaz L, Earp J, Elder J, Cherrington A. Outcome effectiveness of the lay health advisor model among Latinos in the United States: An examination by role type. Health Education Research. 2010;25(5):815–840. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handley M, Schillinger D, Shiboski S. Quasi-experimental designs in practice-based research settings: Design and implementation considerations. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2011;24(5):589–596. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.05.110067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayala G. Effects of a promotor-based intervention to promote physical activity: Familias Sanas y Activas. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(12):2261–2268. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staten L, Cutshaw C, Davidson C, Reinschmidt K, Stewart RA, Roe D. Effectiveness of the Pasos Adelante chronic disease prevention and control program in a US-Mexico border community, 2005-2008. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2012;9:100301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller R, Rollnik S. Motivational interviewing. London: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rollnick S, Mason P, Butler C. Health behavior change: A guide for practitioners. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Resnicow K, Jackson A, Wang T, et al. A motivational interviewing intervention to increase fruit and vegetable intake through Black churches: Results of the Eat for Life trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(10):1686–1693. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holahan PJ, Aronson ZH, Jurkat MP, Schoorman FD. Implementing computer technology: A multiorganizational test of Klein & Sorra's model. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management. 2004;21(1-2):31–50. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arredondo EM, Haughton J, Ayala GX, et al. Fe en Accion/Faith in Action: Design and implementation of a church-based randomized trial to promote physical activity and cancer screening among churchgoing Latinas. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2015;45(Pt B):404–415. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Creswell J. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yin R. Case study research. third. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bazeley P, Jackson K. Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. 2nd. London: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3. London: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage Pubns; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Theim KR, Sinton MM, Goldschmidt AB, et al. Adherence to behavioral targets and treatment attendance during a pediatric weight control trial. Obesity (19307381) 2013;21:394–397. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruebel ML, Heelan KA, Bartee T, Foster N. Outcomes of a Family Based Pediatric Obesity Program - Preliminary Results. International Journal of Exercise Science. 2011;4(4):217–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen CD, Aylward BS, Steele RG. Predictors of attendance in a practical clinical trial of two pediatric weight management interventions. Obesity (19307381) 2012;20(11):2250–2256 2257. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams NA, Coday M, Somes G, Tylavsky FA, Richey PA, Hare M. Risk factors for poor attendance in a family-based pediatric obesity intervention program for young children. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2010;31(9):705–712 708. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181f17b1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baruth M, Wilcox S, Saunders RP. The role of pastor support in a faith-based health promotion intervention. Family & Community Health. 2013;36(3):204–214. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31828e6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bopp M, Wilcox S, Laken M, et al. Using the RE-AIM framework to evaluate a physical activity intervention in churches. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2007;4(4):A87–A87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]