Abstract

Objective: To describe national stimulant treatment patterns among young people focusing on patient age and prescribing specialty.

Methods: Stimulant prescriptions to patients aged 3–24 were analyzed from the 2008 IMS LifeLink LRx Longitudinal Prescription database (n = 3,147,352), which includes 60% of all U.S. retail pharmacies. A subset of young people from 2009 with service claims (n = 197,654) were also analyzed. Denominators were adjusted to generalize estimates to the U.S. population. Population percentages filling ≥1 stimulant prescription during the study year by sex and age group (younger children, 3–5 years; older children, 6–12 years; adolescents, 13–18 years; and young adults, 19–24 years) were determined. Percentages prescribed stimulants by psychiatrists, child and adolescent psychiatrists, pediatricians, and other physicians were also determined along with percentages that were treated for a long or short duration; coprescribed other psychotropic medications; used psychosocial services; and received clinical psychiatric diagnoses.

Results: Population percentages with any stimulant use varied across younger children (0.4%), older children (4.5%), adolescents (4.0%), and young adults (1.7%). Among children and adolescents, males were over twice as likely as females to receive stimulants. Percentages of stimulant-treated young people with ≥1 stimulant prescription from a child and adolescent psychiatrist varied from younger children (19.1%), older children (17.1%), and adolescents (18.2%) to young adults (10.1%), and these percentages increased among those who were also prescribed other psychotropic medications: young children (31.0%), older children (37.9%), adolescents (35.1%), and young adults (15.8%). Antipsychotics were the most commonly coprescribed class to stimulant-treated younger (15.0%) and older children (11.8%), while antidepressants were most commonly coprescribed to adolescents (17.5%) and young adults (23.9%).

Conclusions: Stimulant treatment peaks during middle childhood, especially for boys. For young people treated with stimulants, including younger children, low rates of treatment by child and adolescent psychiatrists highlight difficulties with access to specialty mental health services.

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common psychiatric disorders of childhood (Polanczyk et al. 2007). In the United States, stimulant medications are the dominant treatment for ADHD in school-aged children and adolescents (Froehlich et al. 2007; Garfield et al. 2012). In 2010, stimulants accounted for ∼5.9% of all prescriptions to children (2–11 years) and 7.6% of prescriptions to adolescents (12–17 years). In that year, methylphenidate was the single most widely prescribed medication to adolescents (Chai et al. 2012).

Despite their widespread use, much remains to be learned about stimulant prescribing patterns to young people in the United States. Most previous research on stimulant use has been limited to specific treatment settings (Garfield et al. 2012), payers (Castle et al. 2007; Winterstein et al. 2008), or geographic regions (Rushton and Whitmire 2001; Zito et al. 2007). One analysis of nationally representative household informants estimated that the annual prevalence of any stimulant use was 0.1% for younger children (0–5 years), 5.1% for older children (6–12 years), and 5.1% for adolescents (13–18 years) (Zuvekas and Vitiello 2012). Sample size limitations, however, prevented characterizing stimulant use within these age groups.

The American Association of Pediatrics (AAP) has provided guidelines for the assessment and treatment of ADHD in pediatric practice (Subcommittee on ADHD et al. 2011). According to a national survey of pediatricians, 91% agreed that they should be responsible for identifying ADHD and 70% agreed that they should be responsible for treating ADHD (Stein et al. 2008). Yet tensions exist over the appropriate roles of pediatricians and child and adolescent psychiatrists in managing ADHD. In one survey, a significantly larger percentage of pediatricians than child and adolescent psychiatrists indicated that pediatricians should be responsible for treating ADHD (Heneghan et al. 2008). An understanding of the extent to which child and adolescent psychiatrists, pediatricians, and other physician specialties prescribe stimulants to young people and how these patterns vary by basic patient demographic and clinical characteristics would help to characterize the role each physician group has assumed in the community treatment of ADHD.

In the current report, we estimate the national annual prevalence of stimulant use among young people, aged 3–24, by sex and single year of age. We describe national patterns of young people prescribed stimulants by pediatricians, child and adolescent psychiatrists, and other physicians, and we examine stimulant treatment by duration and in relation to other coprescribed psychotropic medications, use of psychosocial services, and clinical psychiatric diagnoses.

Patients and Methods

We conducted a population-level retrospective observational study of stimulant use in the United States with data from the 2008 IMS LifeLink™ LRx Longitudinal Prescription database and the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2013). The LifeLink LRx data contain deidentified individual prescriptions from ∼33,000 retailers. The IMS data captured 63% of all retail prescriptions in the United States and were nationally representative with respect to age, sex, and insurance. Because the following analyses rely exclusively on deidentified data, they were exempted from human subjects review by the IRBs of Yale University and New York State Psychiatric Institute.

From the 2008 IMS LifeLink LRx database, we obtained data from filled prescriptions for all stimulants and other psychotropic medications by sex and age, as well as the total population covered by the database by sex and age. Only individuals filling a prescription at a retail outlet, including mail order, were captured. To generalize our prevalence estimates of stimulant use to the entire U.S. population of young people, including individuals who did not fill a prescription, we adjusted the denominators using data from MEPS (Olfson et al. 2015). This adjustment permits estimation of stimulant use by age and sex to all civilians aged 1–24 in the United States. The age and sex composition of the IMS population that filled at least one prescription of any kind closely resembled the composition of the corresponding population from the nationally representative MEPS.

The IMS data also include the name of the prescribed medication, days of supply, and specialty of the prescriber. With this information, we calculated the total days of supply for each young person who filled ≥1 stimulant prescription during the study year and examined the percentage who filled prescriptions for ≥120 days (long-term use) and ≤30 days (short-term use). Long-term use estimates maintenance treatment. We further examined the fraction of youth who filled ≥1 stimulant prescription from pediatricians, other primary care physicians, psychiatrists, and child and adolescent psychiatrists during the year (Appendix 1).

Rates of filling any stimulant prescription by single year of age were plotted separately for males and females. We also calculated the percentages of younger children (3–5 years), older children (6–12 years), adolescents (13–18 years), and young adults (19–24 years) receiving stimulants, overall and by sex. Among young people who filled a stimulant prescription, we determined separately for males and females by age group, the percentages with long-term stimulant use; the percentages with prescriptions from various physician specialties; and the percentages with ≥1 prescription during the year for an antipsychotic, antidepressant, mood stabilizer, and anxiolytic. Among youth who used stimulants and at least one other class of psychotropic medication, we also determined by age group, the percentage who received stimulant prescriptions from the various physician specialty groups. Separate analyses examined the percentage of long- and short-term users by the specialty of prescribing physician and age group.

A separate dataset was used for the analysis of clinical diagnoses associated with stimulant prescriptions. The 2009 IMS Medical Claims Database was merged with pharmacy claims from patients common to the 2009 IMS LRx database. In this merged file, which included over 16 million service claims per month from over 100,000 unique physicians across all 50 U.S. states, we examined by age group and sex, the percentage of stimulant-treated youth who received any mental disorder diagnosis during the year. Among those with a mental disorder diagnosis, we examined by age group and sex, the percentage with ≥1 diagnosis of ADHD, disruptive behavior, mood, anxiety, and other mental disorder diagnoses. We also examined the percentages that received ≥1 psychosocial service visits during the year (Appendix 1).

Results

Overall receipt of stimulant medications

The 2008 IMS LRx database included 67,384 younger children, 1,484,633 older children, 1,130,374 adolescents, and 532,345 young adults who filled ≥1 stimulant prescription (total n = 3,147,352). If these figures are projected to the nation, they would represent ∼107,000 (0.4%) young children, 2.36 million (4.5%) older children, 1.79 million (4.0%) adolescents, and 845,000 (1.7%) young adults (Table 1). Based on observed quantities prescribed among those with any prescription, there were ∼429,000 stimulant prescriptions for young children, 13.9 million for older children, 9.6 million for adolescents, and 3.8 million for young adults nationally in 2008.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Any Stimulant Use by Patient, Age Group and Sex, and Among Stimulant Users, Prescribing Specialists by Patient Age Group, United States, 2008

| Age (years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–5 (%) | 6–12 (%) | 13–18 (%) | 19–24 (%) | |

| U.S. population | ||||

| With stimulant prescription in year | 0.44 | 4.46 | 4.03 | 1.76 |

| Among males | 0.66 | 6.66 | 5.54 | 1.80 |

| Among females | 0.23 | 2.47 | 2.55 | 1.72 |

| Among youth with stimulant prescriptions, prescribing specialist | ||||

| Child and adolescent psychiatrists, any | 19.1 | 17.1 | 18.2 | 10.1 |

| Psychiatrists, any | 35.5 | 31.0 | 35.3 | 35.9 |

| Pediatricians, any | 46.2 | 50.5 | 39.9 | 12.6 |

| Nonpediatric primary care providers, any | 11.5 | 15.9 | 21.0 | 43.6 |

IMS LifeLink® Information Assets-LRx Longitudinal Prescription Database, 2008, IMS Health Incorporated.

Age and sex patterns of stimulant use

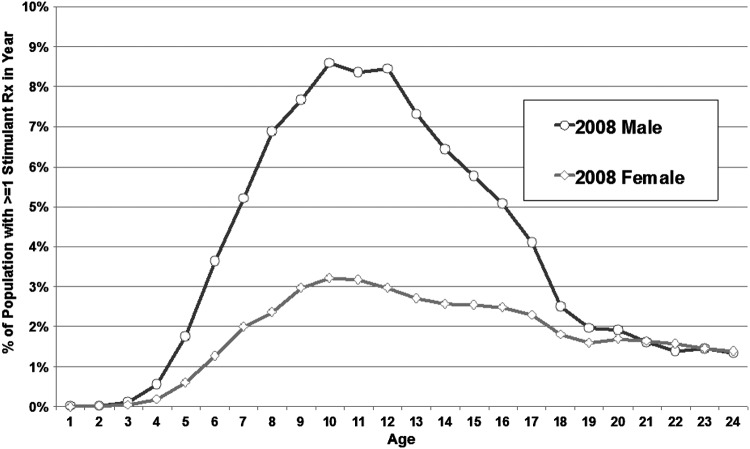

The percentage of young people filling any stimulant prescription was determined by single year of age for males and females (Fig. 1). The percentage of males filling stimulant prescriptions sharply increased from ages 1 to 10, reached a plateau that continued until age 12, rapidly declined to age 18, and then slowly declined until age 24. For females, the increase was more gradual and reached a lower peak at ages 10 and 11 before gradually declining and following a utilization pattern that resembled the male pattern between ages 20 and 24.

FIG. 1.

Percentage of population with any stimulant prescriptions by sex and age, United States, 2008. IMS LifeLink® Information Assets-LRx Longitudinal Prescription Database, 2008, IMS Health Incorporated. Denominators for national estimates of any stimulant use by sex and single year of age based on 2008 National Medical Expenditure Survey data.

Stimulant prescriptions and provider specialty

Of the various physician groups, pediatricians prescribed stimulants to the largest share of children and adolescents. Pediatricians prescribed stimulants to roughly one half of stimulant-treated younger and older children and smaller proportions of the two older groups. For the younger three age groups, child and adolescent psychiatrists prescribed stimulants to approximately one half of those who were treated by psychiatrists (Table 1).

Coprescription of other classes of psychotropic medications

Most stimulant-treated young people in each age group did not fill a prescription for another class of psychotropic medication during the course of the study year. Among younger and older stimulant-treated children, antipsychotic medications were the most commonly coprescribed class of psychotropic medication within the year. Among adolescents and young adults, antidepressants were the most commonly coprescribed psychotropic medication class. Anxiolytics were uncommonly prescribed to these patients before early adulthood (Table 2).

Table 2.

Among Young People with Stimulant Prescriptions, Percentages with Stimulants Only, and Any Antipsychotic, Antidepressant, Mood Stabilizer, and Benzodiazepine Prescriptions by Age Group and Prescribing Physicians, United States 2008

| Age (years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–5 (%) | 6–12 (%) | 13–18 (%) | 19–24 (%) | |

| Among youth with stimulant prescriptions | ||||

| Stimulants only | 82.1 | 82.9 | 74.3 | 69.9 |

| Antipsychotics, any | 15.0 | 11.8 | 13.2 | 7.3 |

| Mood Stabilizers, any | 4.0 | 4.4 | 7.9 | 8.1 |

| Antidepressants, any | 4.1 | 7.9 | 17.5 | 23.9 |

| Anxiolytics, any | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 8.4 |

| Among youth with stimulant prescriptions and ≥1 other psychotropic class, prescribing physicians | ||||

| Child and adolescent psychiatrists, any | 31.0 | 37.9 | 35.1 | 15.8 |

| Psychiatrists, any | 59.8 | 68.2 | 67.9 | 57.1 |

| Pediatricians, any | 28.8 | 25.5 | 18.7 | 6.3 |

| Nonpediatric primary care providers, any | 8.1 | 10.7 | 14.5 | 31.9 |

IMS LifeLink® Information Assets-LRx Longitudinal Prescription Database, 2008, IMS Health Incorporated.

In each of the four age groups, psychiatrists prescribed stimulants to most of the stimulant-treated young people who were also treated with other classes of psychotropic medication. Child and adolescent psychiatrists were more likely than pediatricians to prescribe stimulants to young people who were treated with stimulants and other classes of psychotropic medication (Table 2).

Mental disorder diagnoses

In the 2009 subset with claims data (n = 197,654), most of the stimulant-treated young people did not receive a clinical mental disorder diagnosis. Among those who did receive such diagnoses, a great majority were diagnosed with ADHD. The proportion of stimulant-treated young people who were diagnosed with mood or anxiety disorders increased with patient age, while the proportion diagnosed with disruptive behavior disorders declined with age. Only a minority of stimulant-treated young people in each age group received any psychosocial service visits during the study year (Table 3).

Table 3.

Among Young People with Stimulant Prescriptions, Percentages with Any Psychosocial Service and Any Mental Disorder Diagnosis, and Among this Group Select Mental Disorder Diagnoses, United States 2009

| Age (years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–5 (%) | 6–12 (%) | 13–18 (%) | 19–24 (%) | |

| Among youth with stimulant prescriptions | ||||

| With ≥1 psychosocial service visit | 9.9 | 8.8 | 12.0 | 9.6 |

| With any mental disorder diagnosis | 43.1 | 45.2 | 33.8 | 29.0 |

| Among youth with stimulant prescriptions and a mental disorder diagnosis | ||||

| With ≥1 ADHD diagnosis | 85.4 | 90.6 | 81.4 | 71.9 |

| With ≥1 disruptive behavior diagnosis | 10.0 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 0.7 |

| With ≥1 mood disorder diagnosis | 2.3 | 4.5 | 14.2 | 22.2 |

| With ≥1 anxiety disorder diagnosis | 3.3 | 4.4 | 6.6 | 13.9 |

| With ≥1 other mental disorder diagnosis | 11.8 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 5.9 |

IMS LifeLink® Information Assets-LRx Longitudinal Prescription Database, 2009, IMS Health Incorporated.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Long-term and short-term stimulant use

Among young people who used stimulants, older children were the most likely and younger children were least likely to receive long-term (≥120 days) stimulant treatment. By contrast, younger children were the most likely and older children least likely to receive short-term (≤ 30 days) stimulant treatment. Whether the youth received longer or shorter term stimulant treatment, pediatricians prescribed stimulants to the largest percentages of children and adolescents, and other nonpediatric primary care providers accounted for the largest share of stimulant prescriptions to the young adults (Table 4).

Table 4.

Among Young People with Long-Term and Short-Term Stimulant Use, Percentages with Stimulant Prescriptions from Selected Provider Groups, United States 2008

| Age (years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–5 (%) | 6–12 (%) | 13–18 (%) | 19–24 (%) | |

| Among youth with stimulant prescriptions | ||||

| With long-term stimulant use (≥120 days) | 35.7 | 55.8 | 52.2 | 43.0 |

| Among youth with long-term stimulant prescriptions | ||||

| Pediatricians, any | 49.5 | 52.9 | 42.6 | 14.5 |

| Nonpediatric primary care providers, any | 13.0 | 17.0 | 21.1 | 44.9 |

| Child and adolescent psychiatrists, any | 23.4 | 19.6 | 20.8 | 12.1 |

| Psychiatrists, any | 41.3 | 34.0 | 38.1 | 39.3 |

| Among youth with stimulant prescriptions | ||||

| With short-term stimulant use (≤30 days) | 33.1 | 21.6 | 23.0 | 29.5 |

| Among youth with short-term stimulant prescriptions | ||||

| Pediatricians, any | 42.9 | 46.2 | 35.5 | 10.5 |

| Nonpediatric primary care providers, any | 10.4 | 13.6 | 20.1 | 42.1 |

| Child and adolescent psychiatrists, any | 15.3 | 13.0 | 14.4 | 8.0 |

| Psychiatrists, any | 30.4 | 26.0 | 31.0 | 31.8 |

IMS LifeLink® Information Assets-LRx Longitudinal Prescription Database, 2008, IMS Health Incorporated. Long-term stimulant use defined as ≥120 days of supply during 2008. Short-term stimulant use defined as ≤30 days of supply during 2008.

Discussion

Among young people in the United States, stimulant treatment is highest during the middle childhood years, when use is more than twice as common among boys as girls. Most children, adolescents, and young adults who are treated with stimulants do not receive other classes of psychotropic medication during the course of a year. Among those who do, however, antipsychotics are the class most commonly coprescribed for children, while antidepressants are the most commonly prescribed for adolescents and young adults.

Most U.S. children and adolescents who are treated for ADHD receive stimulant medications (Olfson et al. 2014) and ADHD is easily the most common mental disorder diagnosed among young people who are treated with stimulants. Such associations provide a basis for considering community stimulant prescribing practices in relation to ADHD prevalence. The rate of stimulant treatment for older children (4.5%) is below the estimated community prevalence of ADHD in children (6.5%; Polanczyk and Rohde 2007). This pattern is consistent with the view that delays in treatment seeking contribute to undertreatment of ADHD during childhood.

Community epidemiological studies indicate that ADHD is ∼2.5 times more common in boys than girls (Staller and Faraone 2006; Polanczk and Rohde 2007). A roughly comparable difference in population stimulant treatment rates was observed between males and females. This pattern contrasts with early studies of clinical samples that reported much higher male to female ratios of ADHD ranging from 6:1 to 9:1 (Gaub and Carlos 1997). Treatment seeking patterns may have changed over the last several years to narrow the gender difference in the rates of stimulant treatment. Different problems may bring boys and girls with ADHD to treatment with academic problems and behavioral symptoms most strongly related to ADHD treatment seeking for boys and comorbid depression most strongly related to ADHD treatment for girls (Graetz et al. 2006).

Rates of stimulant treatment peak around age 12 and then fall during the adolescent and early adult years. Roughly one-third of children with ADHD are estimated to continue to have ADHD as adults (Kessler et al. 2005; Barbaresi et al. 2013). Crude stimulant treatment rates indicate that approximately similar decrement occurs in stimulant prescriptions from adolescence to young adulthood. In addition to symptom remission that occurs as part of the natural course of some young people with ADHD (Holbrook et al. 2014), social factors may contribute to lower rates of stimulant treatment of young adults than adolescents. During late adolescence, young people may assume greater control over their healthcare, parents may become less involved in daily medication administration, and stimulant refusal may become more common. Several studies report that older patient age is associated with lower adherence and persistence of stimulant treatment (Gau et al. 2006; Atzori et al. 2009; Lawson et al. 2012).

A substantial number of preschool-aged children, 3–5 years, were treated with stimulant medications. The assessment and management of ADHD in preschool children pose particularly complex clinical challenges. Given wide variation in attention span, motor activity level, and impulsivity among typically developing preschool children (Ghuman and Ghuman 2013), it is recommended that initial assessments of preschool children include parent report instruments, multiple appointments, and a multidisciplinary team approach (Gleason et al. 2007). The finding that child and adolescent psychiatrists are involved in the medication management of only around one in five preschool children who are prescribed stimulants poses a challenge to the community treatment of ADHD in preschool children.

Psychiatrists, including child and adolescent psychiatrists, were more often involved than pediatricians in the stimulant treatment of children and adolescents who received other classes of psychotropic medications. This pattern is consistent with a sorting process, through referral and help seeking, that results in young people with more complex clinical presentations finding their way to specialized services. Prescribing differences between psychiatrists and pediatricians may also contribute to the tendency for psychiatrists to treat youth who receive stimulants in combination with other psychotropic medications. Other factors, including difficulties identifying local child psychiatrists to assist with the assessment and management of young children with ADHD related to shortages in some geographic regions (Power et al. 2008), financial barriers (Bishop et al. 2014), and variation in the distribution of medical specialties by practice setting, may contribute to the observed prescribing patterns across medical specialists.

Pediatricians commonly view the management of ADHD as within the scope of their practice (Power et al. 2008; Stein et al. 2008; Fremont et al. 2009). We found that approximately half of all children in the United States who are treated with stimulants receive them from pediatricians. However, pediatricians play a considerably smaller role in the psychopharmacological management of young people who are treated with stimulants and other psychotropic medications. Help seeking and referral patterns may lead parents of children and adolescents with more complex behavioral healthcare needs to more often seek treatment from psychiatrists. However, pediatricians are much more likely to perceive that they are responsible for treatment of ADHD than for treatment of behavioral management problems or other common childhood psychiatric problems (Stein et al. 2008).

Of the four age groups, preschool children were the most likely to receive short-term stimulant treatment and least likely to receive long-term stimulant treatment. A higher rate of early stimulant termination may reflect tolerability problems, lack of efficacy, or greater caution exercised by prescribing physicians or parents in the care of younger children.

Most stimulant-treated young people did not receive any psychosocial services during the study year. While some parents perceive psychosocial interventions as more acceptable and less stigmatizing than pharmacological treatments for ADHD (dosReis et al. 2003; Dreyer et al. 2010), it is possible that financial concerns (Bussing et al. 2003), lack of parent time (Krain et al. 2005), regional scarcities of qualified therapists, or other system factors (Epstein et al. 2014) such as an absence of referral or long wait times contribute to the observed treatment patterns.

Because of uncertainty over the efficacy, tolerability, and long-term safety of stimulants in preschool children (Greenhill et al. 2006; Wigal et al. 2006) and evidence supporting the effectiveness of behavioral interventions (Sonuga-Barke et al. 2001; Webster-Stratton et al. 2011), several practice guidelines recommend parent- or teacher-administered behavior therapy as the first-line treatment for ADHD in preschool children (Gleason et al. 2007; National Collaborating Center 2009; Subcommittee ADHD 2011). Yet only around 1 in 10 stimulant-treated preschoolers received any psychosocial services. Preschool children were also the least likely of the four age groups to receive long-term stimulant treatment.

The relatively high rate of coprescribed antipsychotic medications poses potential safety concerns (Memarzia et al. 2014). Because of the paucity of research on the efficacy of antipsychotic medications in the management of ADHD, especially among young children, and uncertainties over their long-term safety, the coprescription of antipsychotics with stimulants to preschool-aged children merits further research.

The analysis has several limitations. First, the IMS prescription data capture medicines purchased rather than consumed. Second, no data were available concerning the effectiveness or safety of the stimulants. Third, although the population denominator was adjusted for the percentage of the population by age and sex, who reported not filling a prescription medication in the study year, it is not possible to estimate the precision of the derived estimates. Fourth, right and left censoring of the calendar year data results in underestimation of the length of stimulant use. Finally, the analyses are primarily based on 2008 dispensing patterns and since that time prescribing practices may have changed (Visser et al. 2014), especially among young adults.

Conclusions

An analysis of U.S. national stimulant prescribing patterns to young people, 3–24 years of age, reveals that stimulant treatment peaks during late childhood and early adolescence with rates that are nearly three times as high for boys as girls. The rate of stimulant treatment markedly declines during later adolescence, particularly for males, so that by early adulthood males and females have comparable rates of stimulant treatment. Despite progress in developing effective psychosocial interventions for ADHD, only a small proportion of children, adolescents, and young adults who are treated with stimulants receive any psychosocial services. In addition, most stimulant-treated young people in each age group do not receive their prescriptions from psychiatrists.

Clinical Significance

National patterns in stimulant treatment are broadly consistent with the known epidemiology of ADHD as a male predominant childhood disorder that demonstrates persistence into early adulthood for a substantial minority of individuals. Low rates of psychosocial interventions raise concerns over missed opportunities to address social and interpersonal deficits that are common in ADHD and over reliance on stimulants for young children with ADHD. At the same time, the high proportion of stimulant-treated young children, ages 3 to 5 years, who receive their prescriptions exclusively from pediatricians and other non-psychiatrist physicians raises concerns over critical shortages and problems with access to psychiatric services for young children.

Appendix 1.

ICD-9-CM Codes Used to Define Mental Disorder Groups, CPT Codes Used to Define Psychosocial Services, and Specialty Codes Used to Define Physician Specialty Groups

| Mental disorder group | ICD-9-CM codes |

|---|---|

| Any mental disorder | 290–319 |

| ADHD | 314.xx |

| Disruptive behavior disorders | 312.0x, 312.1x, 312.2x, 312.3x, 312.4x, 312.81, 312.82, 312.89, 312.9x, 313.81 |

| Mood disorders | 296.0x,296.1x, 296.2x, 296.3x, 296.4x, 296.5x, 296.6x, 296.7x, 296.8x, 298.0x, 301.13, 300.4x, 311.xx |

| Anxiety disorders | 300.0x, 300.2x, 309.21, 309.81, 308.3x, 293.84 |

| Other mental disorders | 290–319, not defined above. |

| Service | CPT codes |

| Psychosocial services | 90810–90815, 90823–29, 90832, 90834, 90833, 90836, 90837, 90838, 90839, 90840, 90845–90847, 90849, 90853, 90857 |

| Physician specialties | Specialty codes |

| Child and adolescent psychiatrists | Child Psychiatry, Pediatrics/Psychiatry/Child Psychiatry |

| Psychiatrists | Addiction Psychiatry, Child Psychiatry, Geriatric Psychiatry, Family Practice, Psychiatry, Forensic Psychiatry, Internal Medicine/Psychiatry, Psychiatry/Neurology, Psychoanalysis, Pain medicine (Psychiatry), Pediatrics/Psychiatry/Child Psychiatry, Neurodevelopmental Disabilities/Psychiatry |

| Pediatricians | Adolescent Medicine, Pediatrics, Internal Medicine/Pediatrics, Pediatrics/Emergency Medicine, Child Abuse Pediatrics, Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics, Neurodevelopmental Disabilities/Pediatrics |

| Nonpediatric primary care providers | Family Medicine, Family Practice, Family Practice, Geriatric, General Practice, Internal Medicine/Family Practice, Internal Medicine, Internal Medicine/Emergency Medicine, Internal Medicine/Preventative Medicine, Public Health and General Preventative Medicine, Physician Assistant, Nurse Practitioner, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Obstetrics |

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Authors' Contribution

M.O. contributed to the conception and design of the study, drafted the article, approved the final article as submitted, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the article. M.K. analyzed and interpreted the data, revised the article for important intellectual content, approved the final article as submitted, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the article. M.S. contributed to the conception and design of the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, revised the article for important intellectual content, approved the final article as submitted, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the article.

Disclosures

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, MEPS-HC panel design and data collection process. Available at http://meps.ahrq.gov/survey_comp/hc_data_collection.jsp Accessed on November5, 2015

- Atzori P, Usala T, Carucci S, Danjour F, Zuddas A: Predictive factors for persistent use and compliance of immediate-release methylphenidate: A 36-month naturalistic study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 19:673–681, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Voigt RG, Killian JM, Katusic SK: Mortality, ADHD, and psychosocial adversity in adults with childhood ADHD: A prospective study. Pediatrics 131:637–644, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA: Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry 71:176–181, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Zima BT, Gary FA, Garvan CW: Barriers to detection, help-seeking, and service use for children with ADHD symptoms. J Behav Health Serv Res 30:176–189, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle L, Aubert RE, Verbugge RR, Khalid M, Epstein RS: Trends in medication treatment of ADHD. J Atten Disord 10:335–342, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai G, Governale L, McMahon AW, Trinidad JP, Staff J, Murphy D: Trends in outpatient prescription drug utilization in US children, 2002–2010. Pediatrics 130:23–31, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dosReis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, Soeken KL, Mitchell JW, Ellwood LC: Parental perceptions and satisfaction with stimulant medication for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Dev Behav Pediatr 24:155–162, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer A, O'Laughlin L, Moore J, Milam Z: Parental adherence to clinical recommendations in an ADHD evaluation clinic. J Clin Psychol 66:1101–1120, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JN, Kelleher KJ, Baum R, Brinkman WB, Peugh J, Gardner W, Lichtenstein P, Langberg J: Variability in ADHD care in community-based pediatrics. Pediatrics 134:1136–1142, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremont WP, Nastasi R, Newman N, Roizen NJ: Comfort level of pediatricians and family medicine physicians diagnosing and treating child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med 38:153–168, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich TE, Lanphear BP, Epstein JN, Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Kahn RS: Prevalence, recognition, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a national sample of US children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161:857–864, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield CF, Dorsey ER, Zhu S, Huskamp HA, Conti R, Dusetzina SB, Higasi A, Perrin JM, Kornfield R, Alexander GC: Trends in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ambulatory diagnosis and medical treatment in the United States, 2000–2010. Acad Pediatr 12:110–116, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SS, Shen HY, Chou MC, Tang CS, Chiu YN, Gau CS: Determinants of adherence to methylphenidate and the impact of poor adherence on maternal and family measures. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 16:286–297, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaub M, Carlson CL: Gender differences in ADHD: A meta-analysis and critical review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:1036–45, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghuman JK, Ghuman HS: Pharmacologic intervention for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in preschoolers: Is it justified? Pediatr Drugs 15:1–8, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason MM, Egger HL, Emslie GJ, Greenhill LL, Kowatch RA, Lieberman AF, Luby JL, Owens J, Scahill LD, Scheeringa MS, Stafford B, Wise B, Zeanah CH: Psychopharmacological treatment for very young children: Contexts and guidelines. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 246:1532–1572, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graetz BW, Sawyer MG, Baghurst P, Hirte C: Gender comparisons of service use among youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Emot Behav Disord 14:2–11, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill L, Kollins S, Abikoff H, McCracken J, Riddle M, Swanson J, McGough J, Wigal S, Wigal T, Vitiello B, Skrobala A, Posner K, Ghuman J, Cunningham C, Davies M, Chuang S, Cooper T: Efficacy and safety of immediate-release methylphenidate treatment for preschoolers with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45:1284–1293, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneghan A, Garner AS, Storfer-Isser A, Kortepeter K, Stein REK, Horwitz SM: Pediatricians' role in providing mental health care for children and adolescents: Do pediatricians and child and adolescent psychiatrists agree? J Dev Behav Pediatr 29:262–269, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook JR, Cuffe SP, Cai B, Visser SN, Forthofer MS, Bottai M, Ortaglia A, McKeown RE: Persistence of parent-reported ADHD symptoms from childhood through adolescences in a community sample. J Atten Disord 20:11–20, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Adler LA, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Faraone SV, Greenhill LL, Jaeger S, Secnik K, Spencer T, Ustun TB, Zaslavsky AM: Patterns and predictors of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder persistence into adulthood: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry 57:1442–1451, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krain AL, Kendall PC, Power TJ: The role of treatment acceptability in the initiation of treatment for ADHD. J Attent Dis 9:425–434, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson KA, Johnsrud M, Hodgkins P, Sasane R, Crismon ML: Utilization patterns of stimulants in ADHD in the Medicaid population: A retrospective analysis of data from the Texas Medicaid program. Clin Ther 34:944–956, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memarzia J, Tracy D, Giaroli G: The use of antipsychotics in preschoolers: A veto or a sensible loast option? J Psychopharmacol 28:303–319, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management of ADHD in Children, Young People and Adults. London, British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, Laje G, Correll CU: National trends in mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults by office-based physicians. JAMA Psychiatry 71:81–90, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M: Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 72:136–142, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohe LA: The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: A systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry 164:942–948, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk G, Rohde LA: Epidemiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder across the life span. Curr Opin Psychiatry 20:386–392, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Mautone JA, Manz PH, Frye L, Blum NJ. Managing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in primary care: A systematic analysis of roles and challenges. Pediatrics 121:e65–e72, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton JL, Whitmire MT: Pediatric stimulant and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor prescription trends 1992 to 1998. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 155: 560–565, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJ, Daley D, Thompson M, Laver-Bradbury C, Weeks A: Parent-based therapies for preschool attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A randomized, controlled trial with a community sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40:402–408, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staller J, Faraone SC: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in girls: Epidemiology and management. CNS Drugs 20:107–123, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein REK, Horwitz SM, Storfer-Isser A, Heneghan A, Olson L, Hoagwood KE: Do pediatricians think they are responsible for identification and management of child mental health problems? Results of the AAP periodic survey. Ambul Pediatr 8:11–17, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management, Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, DuPaul G, Earls M, Feldman HM: ADHD: Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 128:1007–1022, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, Ghandour RM, Perou R, Blumberg SJ: Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003–2011. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53:34–46, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Reid M, Beauchaine T: Combining parent and child training for young children with ADHD. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 40:191–203, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigal T, Greenhill L, Chuang S, McGough J, Vitiello B, Skrobala A, Swwanson J, Wigal S, Abikoff H, Kollins S, McCracken J, Riddle M, Posner K, Ghuman J, Davies M, Thorp B, Stehli A: Safety and tolerability of methylphenidate in preschool children with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45:1294–303, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterstein AG, Gerhard T, Shuster J, Zito J, Johnson M, Liu H, Saidi A: Utilization of pharmacologic treatment in youths with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Medicaid database. Ann Pharmacother 42:24–31, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zito JM, Safer DJ, Valluri S: Psychotherapeutic medication prevalence in Medicaid-insured preschoolers. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 17:195–203, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH, Vitiello B: Stimulant medication use in children: A 12-year perspective. Am J Psychiatry 169:160–166, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]