Companion diagnostics are in vitro clinical laboratory assays designed to predict the efficacy of a targeted cancer therapy through assessment of 1 or more biomarkers whose status in a patient’s neoplasm assists in determining whether a drug may or may not be effective. Companion diagnostics can be developed after a drug has been marketed, or they may be codeveloped alongside a targeted cancer drug through clinical trials. Until recently, most companion diagnostics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have been designed along a linear paradigm of “one drug/one biomarker.” However, the limitations of this approach are becoming apparent as in vitro diagnostics are shifting to high-throughput assays, the scope of cancer heterogeneity at the molecular and proteomic levels is becoming increasingly known, and the armamentarium of targeted therapies continues to expand.1 Novel high-throughput testing platforms, namely next-generation sequencing (NGS) and mass spectrophotometry (MS) proteomics, are gradually disrupting traditional diagnostic assays and ushering in a new paradigm of companion diagnostics we refer to aptly as next-generation companion diagnostics.

Selection of the optimal in vitro diagnostics platform for companion diagnostics is currently in flux. By permitting the simultaneous assessment of multiple analytes, NGS and MS proteomics are challenging the traditional concept of using focused, low-throughput companion diagnostics, such as immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization, in favor of a more expansive assessment of the molecular and proteomic makeup of cancer samples. Amidst such uncertainty, the major stakeholders in companion diagnostics—clinical laboratories and the pharmaceutical industry—have been caught between a need to adopt new high-throughput in vitro diagnostics platforms and meeting the requirements of FDA approval (still largely focused on low-throughput companion diagnostics) as new targeted cancer drugs enter the development pipeline in unprecedented numbers. As such, progress in the field of companion diagnostics appears to be held back by the ripple of changes happening in the in vitro diagnostics space, risking a slowing in the pace of drug/biomarker development and increased safety risks and costs. Despite encouraging advances, such as the recent FDA decision to grant the first marketing authorization for an NGS platform (MiSeqDx; Illumina, San Diego, California),2 more concerted efforts are needed to translate such advances into progress in the companion diagnostics arena.

The basic premise of next-generation companion diagnostics is the use of an FDA-approved drug/biomarker combination based on a cancer’s genomic and proteomic profile assessed on high-throughput platforms such as NGS and MS proteomics. However, while such an approach is already within reach, some hurdles still stand in the way of its full-scale implementation. In this letter, we discuss limitations of traditional companion diagnostics and the potential of next-generation companion diagnostics to overcome these limitations. We also propose a broad organizational framework for overcoming current hurdles and facilitating the use of next-generation companion diagnostics in cancer drug selection and biomarker selective clinical trial design.

LIMITATIONS OF CURRENT IN VITRO COMPANION DIAGNOSTICS

Companion diagnostics have been shown to increase the safety and effectiveness of targeted cancer therapies in a number of neoplasms, including breast cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, chronic myelogenous leukemia, B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and others. As stipulated by US federal statutes, companion diagnostics must be performed in a clinical laboratory certified in accordance with the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) and accredited by a federally designated accreditation agency such as the College of American Pathologists (CAP). Like other in vitro diagnostic tests, companion diagnostic assays performed in a CLIA-certified laboratory are generally labeled as FDA-approved or laboratory-developed tests.

One of the main limitations of traditional companion diagnostics is the narrow scope of biomarker evaluation and the often high tissue requirements if multiple single biomarker tests are needed for therapy selection. Several discoveries over the past few years have demonstrated that the mere detection of a therapeutic target is not sufficient to predict drug efficacy and needs to be supplemented by additional data to further assess for resistance. For instance, patients with colorectal cancer whose tumor expresses the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) are usually resistant to anti-EGFR therapy if the tumor also harbors mutations in KRAS or NRAS.3 In lung cancer, anti-EGFR therapy is also ineffective in the presence of KRAS mutations even in patients whose tumor has activating mutations in the EGFR kinase domain. Additionally, detection of the BCR/ABL fusion in chronic myelogenous leukemia is not always sufficient to predict response to imatinib because mutations in the ABL kinase domain confer resistance and necessitate a switch to second-line or third-line tyrosine kinase inhibitors. An additional problem with traditional companion diagnostics is that low-throughput assays require greater amounts of tissue than next-generation assays. This limitation is becoming particularly acute in solid tumors that are commonly diagnosed using limited tissue specimens, and it underscores the importance of a more comprehensive genomic/proteomic profiling for targeted therapy selection in cancer.4

In addition to the biological and logistic limitations of traditional companion diagnostics, the economic implications for using single biomarker assays are becoming more significant as reimbursement for high-complexity laboratory tests continues to decrease. In molecular diagnostics, mainly as a result of recent changes in reimbursement models, surveying for more than a handful of hotspot mutations by traditional polymerase chain reaction and sequencing methods is more laborious and therefore more expensive than the cost of screening for such mutations by NGS (discounting the price of capital equipment).

CERTIFIED ADVANCED COMPANION DIAGNOSTICS FACILITIES

We call for a gradual prospective replacement of traditional companion diagnostics approaches with next-generation companion diagnostics aimed at characterizing the mutational profile and proteomic complement of a tumor as a foundation for targeted drug selection. Such next-generation companion diagnostics data would be the basis for selection of targeted therapies along a new paradigm of accredited in vitro diagnostics platform → biomarker detection → drug selection. Ideally, such an approach would be performed on a primary tumor at diagnosis and/or at relapse. It is explicitly acknowledged that not all patients will need genomic and/or proteomic profiling for next-generation companion diagnostics, and in some instances such profiling would be best reserved for refractory disease.

A number of prerequisites are needed to ensure that such a new paradigm in companion diagnostics happens with utmost consideration to patient safety, fiduciary responsibility, and established clinical practices. These prerequisites are the purview of several players in the companion diagnostics sphere, including clinical laboratories, pharmaceutical industry, CAP, oncology societies, private third-party payers, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the FDA. A summary of such prerequisites is provided in the Table.

Table.

Prerequisites for Transition to Next-Generation Companion Diagnostics

|

Abbreviations: CAP, College of American Pathologists; CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; MS, mass spectrometry; NGS, next-generation sequencing.

To begin laying the foundation for a transition to next-generation companion diagnostics, a certification process for clinical laboratories wishing to provide next-generation companion diagnostics should be instated. Such certification would be appropriate if a CLIA-certified laboratory is offering next-generation companion diagnostic services where results are used to support cancer therapy decisions pursuant to FDA-approved indications or in the context of a registered clinical trial. It is recommended that certification of such facilities would be granted by the CAP under commission from the FDA.

The balance between regulation, oversight, and efficiency is often delicate. A recent opinion letter5 details the difficulties in achieving optimal balance between imposing FDA regulatory oversight and facilitating advances in the development of innovative biomarker testing and trial designs. While the specifics of the certification requirements are beyond the scope of this letter, they would be founded on core CAP Laboratory Accreditation Program checklist items, with added emphasis on the complex issues pertaining to next-generation companion diagnostics, including test/instrument validation standards, minimum criteria for quality control and quality assurance, proficiency testing requirements, standardization of required report data elements, standardized procedures for data archiving, and feedback into clinical outcomes databases.

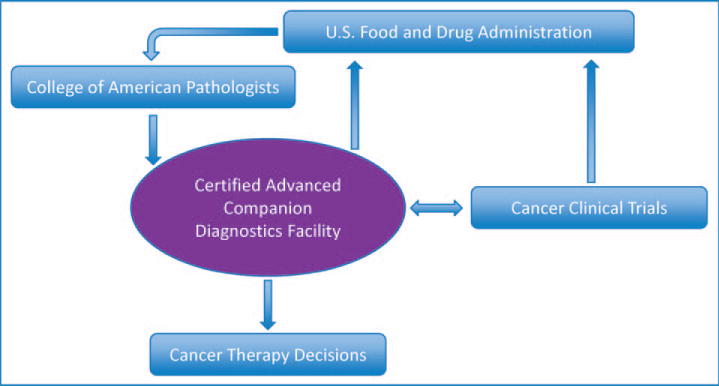

We propose that laboratories that achieve successful accreditation under such a program would be designated as a Certified Advanced Companion Diagnostics Facility (CACDF). The CACDF accreditation process (Figure) should be implemented prospectively without impact on existing established companion diagnostics assays. While attaining CACDF status could be voluntary during an initial grace period, we believe that mandating such certification for laboratories that offer next-generation companion diagnostics would be in the best interest of the public and in line with the spirit of CLIA and its amendments. At the least, CACDF laboratories would initially be mandatory sites for next-generation companion diagnostics for National Cancer Institute-sponsored clinical trials. Among the advantages envisioned for CACDF status are (1) enhancing patient safety in biomarker-selective clinical trials, (2) reducing variability of testing to determine FDA-approved eligibility for a targeted therapy, and (3) a shorter path to FDA approval for a targeted therapeutic agent evaluated in a CACDF laboratory.

Figure.

Proposed creation of Certified Advanced Companion Diagnostics Facilities accredited by the College of American Pathologists under commission by the US Food and Drug Administration in accordance with the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health K12 award (CA139160-01A), University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center Award in Precision Oncology, and LLK Foundation Award (Dr Catenacci). The authors thank L. Jeffrey Medeiros, MD, for critical review of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors have no relevant financial interest in the products or companies described in this article.

Contributor Information

Dr Joseph D. Khoury, Division of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Department of Hematopathology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Daniel V. T. Catenacci, Department of Medicine, Section of Hematology/Oncology, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

References

- 1.Parkinson DR, Johnson BE, Sledge GW. Making personalized cancer medicine a reality: challenges and opportunities in the development of biomarkers and companion diagnostics. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(3):619–624. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins FS, Hamburg MA. First FDA authorization for next-generation sequencer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(25):2369–2371. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1314561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, et al. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(11):1023–1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Food Drug Administration. Guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff: in vitro companion diagnostic devices. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm262292.htm. Accessed November 25, 2013.

- 5.Kurzrock R, Kantarjian H, Stewart DJ. A cancer trial scandal and its regulatory backlash. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(1):27–31. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.College of American Pathologists. Proposed approach to oversight of laboratory developed tests. http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/advocacy/ldt/oversight_model.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2013.

- 7.Catenacci D, Polite B, Henderson L. Towards personalized treatment for gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma (GEC): strategies to address tumor heterogeneity—PANGEA. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 3) Abstract 66. [Google Scholar]