Abstract

Wilm's tumor 1 interacting protein (Wtip) was identified as an interacting partner of Wilm's tumor protein (WT1) in a yeast two-hybrid screen. WT1 is expressed in the proepicardial organ (PE) of the heart, and mouse and zebrafish wt1 knockout models appear to lack the PE. Wtip's role in the heart remains unexplored. In the present study, we demonstrate that wtip expression is identical in wt1a-, tcf21-, and tbx18-positive PE cells, and that Wtip protein localizes to the basal body of PE cells. We present the first genetic evidence that Wtip signaling in conjunction with WT1 is essential for PE specification in the zebrafish heart. By overexpressing wtip mRNA, we observed ectopic expression of PE markers in the cardiac and pharyngeal arch regions. Furthermore, wtip knockdown embryos showed perturbed cardiac looping and lacked the atrioventricular (AV) boundary. However, the chamber-specific markers amhc and vmhc were unaffected. Interestingly, knockdown of wtip disrupts early left-right (LR) asymmetry. Our studies uncover new roles for Wtip regulating PE cell specification and early LR asymmetry, and suggest that the PE may exert non-autonomous effects on heart looping and AV morphogenesis. The presence of cilia in the PE, and localization of Wtip in the basal body of ciliated cells, raises the possibility of cilia-mediated PE signaling in the embryonic heart.

Keywords: WT1, wtip, tcf21, proepicardial organ, cilia, heart looping, atrioventricular boundary, left-right asymmetry, zebrafish

Introduction

The heart is one of the first organs to form during development from the lateral plate mesoderm (1–3). The primitive heart tube consists of two layers: The endocardium and the myocardium (4). Progenitor cells in the lateral plate mesoderm migrate toward the midline, where they form the two-layered heart tube. Subsequent morphological changes are necessary to shape this primitive heart tube into the chambered heart organ and for the atrioventricular (AV) boundary to develop between chambers that provide directional flow. In addition to the endocardium and myocardium, a third cellular layer, the epicardium, develops from an extracardiac population of cells called the proepicardial organ (PE) (5–12).

The mesodermally-derived epicardium covers the myocardial layer and is known to provide signaling required for proper development of the heart (13–15). However, the molecular regulation of epicardial function is just beginning to be investigated. Wilm's tumor protein (wt1), vascular cell adhesion protein 1 and α4 integrin genes are essential for epicardium formation. Targeted mutagenesis of these genes in mice provided genetic evidence supporting a role in cardiac development (16–19). Additional evidence suggested that the PE contributes to the development of the coronary vessels, and is required for continued cardiac development and function (5–11,20,21).

Previous studies indicated that in zebrafish, similar to other vertebrates, the PE can be distinguished morphologically at 48 h post fertilization (hpf) as a group of cells located in close proximity to the ventral wall of the heart (22,23). The PE is characterized by the expression of wt1a, transcription factor 21 (tcf21), and T box 18 (tbx18) at 48 hpf (22,23). Specification of the PE requires a bone morphogenic protein (BMP) ligand, which is not, as previously assumed, derived from the liver bud (23). Instead, cardiac-specific bmp4 signaling from the myocardium induces PE specification. Independent from Bmp4 signaling, tbx5 expression in the lateral mesoderm during the early somite stages is also required for PE specification (23). Previous studies in adult zebrafish hearts indicate that the epicardium forms a smooth surface covering the entire heart wall. Additionally, it was discovered that partial amputation of the adult heart elevated the expression of tbx18 and retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 2, which suggests that epicardial genes serve a critical role in the response to injury (24–26). The activated epicardial cells proliferate and undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, which requires platelet-derived growth factor (27) and β-catenin and retinoic acid signaling (21). The developmentally activated epicardial cells quickly invade the proliferating myocardium at the site of injury and create a dense vascular network that is likely to encourage regeneration (24–27).

In addition to its role in response to heart injury, the epicardium has important regulatory functions in the normal development of the myocardium (17,18,28–31). Despite the central role of epicardial signaling during heart development and repair, the molecular signals driving specification of the PE remain poorly understood.

In chicks, the PE first forms in a bilaterally symmetrical fashion, and then develops asymmetrically. Disruption of genes required for specifying right-sidedness in the body, such as fibroblast growth factor 8 (fgf8) or snail homolog 1 (snail1), prevented PE specification (32). In mice, the dependence of PE specification on the left-right (LR) body axis is unclear. In this organism, both PE precursors develop equally on both sides, and later fuse at the midline to generate the PE (33). Establishment of the LR axis in the zebrafish heart depends on global LR cues that are generated by cilia during early gastrulation stages (34). Abnormal LR development can affect cardiac looping during vertebrate morphogenesis. Therefore, some cardiac defects that are associated with the abnormal positioning of the cardiac chambers or with vessel malformation are secondary to altered LR development (35). However, some patients demonstrate heterotaxy of the heart without other obvious LR defects, suggesting that ciliary function may also have an important role in cardiovascular morphogenesis itself (36–38). Slough et al (39) reported the presence of mono-cilia in several areas of the mouse embryonic heart, suggesting a role for cilia in cardiac morphogenesis. Furthermore, hearts in kinesin-3a (Kif3a) mutants developed abnormal endocardial cushions (ECCs) and thinner compact myocardium, and completely lacked cardiac cilia (39). Additionally, the compact myocardium was thinner in embryos mutant for polycystic kidney disease 2, a protein that functions as a mechanosensor in the kidney and node (39).

The WT1-interacting protein (Wtip) was originally identified as an interacting partner of WT-1 in a yeast two-hybrid screen (40). Recent studies and previous work by our group revealed the following roles for Wtip: i) Wtip interacts with the C-terminus of receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 2 in yeast and mammalian cells (41); ii) Ajuba LIM proteins [Ajuba, LIM domain containing 1 (LIMD1), and Wtip] interact with Snail to remodel epithelial dynamics (42,43); iii) Wtip is a LIM domain protein of the Ajuba/Zyxin family, which is enriched in the basal bodies of cells in the pronephros and Kupffer's vesicle in zebrafish (44). In zebrafish, wtip deletion leads to pronephric cysts, hydrocephalus, body axis curvature and pericardial edema (44); iv) cryptic deletion in the human wtip gene was reported to cause hypospadias, accompanied by congenital heart disease (45), but the roles for Wtip in the heart are unknown. Since Wtip plays a role in ciliopathy (44), interacts with wt1 (40), which is expressed in the PE, and Wtip depletion leads to pericardial edema (44), we hypothesized that Wtip function in the heart may be associated with PE specification and may be involved in LR patterning.

In the present study, we show that cardiac expression of wtip mirrors wt1a, tcf21, and tbx18 expression, confirming that wtip is expressed in the PE. This is the first report, to the best of our knowledge, to describe how Wtip, a basal body protein, is important for PE specification, heart looping, AV formation and LR patterning.

Materials and methods

Zebrafish maintenance

All animal experiments were performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. Danio rerio (AB strain) were maintained and raised at 28.5°C under a 14-h light/10-h dark cycle. Zebrafish embryos were kept in 0.5X E2 egg medium (7.5 mM NaCl, 0.25 mM KCl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 0.075 mM KH2PO4, 0.025 mM Na2HPO4, 0.35 mM NaHCO3, 0.01% methylene blue). To suppress pigmentation of zebrafish embryos, 0.0045% 1-Phenyl-2-thiourea (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to egg medium as needed. Embryos and larvae were staged according to h post-fertilization (hpf) or days post-fertilization (dpf) (46).

Morpholino and mRNA injections

A translational blocking morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) targeted against the 5′UTR of wtip (wtipMO; 5′-GATCCTCGTCGTATTCATCCATGTC-3′; 44), wt1a (wt1aMO: 5′-GAGCAAGAGATACTGACCTGAAGGC-3′; 22), and randomized control MO (conMO: 5′-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3′) were obtained from Gene Tools, LLC (Philomath, OR, USA). A volume of 4.6 nl with a concentration of 0.225 mM wtipMO, 0.056 mM wtipMO, 0.25 mM wt1aMO, 0.0625 mM wt1aMO, and 92 pg wtip mRNA was injected at the one-cell stage using a nanoliter 2000 microinjector (World Precision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, FL, USA). Zebrafish wtip mRNA was synthesized with T7 RNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), after linearization of the pCR®-BluntII-TOPO®-wtip construct with HindIII (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). All mRNAs were purified using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). Microinjections into 1-cell embryos were performed as described by Feng et al (47). To knockdown wtip specifically in dorsal forerunner (DFCs), wtipMO was injected into the yolk cell of the ~1,000-cell stage embryos as previously described (48).

In situ hybridization

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed as previously described (49,50), using the following probes: wtip, wt1a, tcf21, tbx18, bmp4, LR determination factor 1 (lefty1), lefty2, southpaw (spaw), cardiac myosin light chain 2 (cmlc2), α-cardiac myosin heavy chain (amhc), ventricular MHC (vmhc) and natriuretic peptide A (nppa) (34,44,51–54). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) DNA templates were used for wt1a, tcf21, bmp4, lefty1, lefty2, spaw, cmlc2, amhc, vmhc and nppa. DNA templates were used for wtip and tbx18. We used the following primers to prepare the PCR DNA template for reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and 2nd PCR for wt1a (765 bp): wt1a-51F1 5′-CCGGTGGAAACGGTAACTGTA-3′; wt1a-1161R1 5′-TCTGCAGTTGAAGGGCTTCTC-3′; wt1a-240F2 5′-GCACTTCTCCGGACAGTTCAC-3′; and wt1a-1004R2T7 5′-GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAACCTGCGACCACAGTCT-3′. For tcf21 (682 bp), we used the following primers: tcf21-68F1 5′-TCATCTCCACGTCCAGTCAGA-3′; tcf21-876R1 5′-CACACTGTTGCCTTGAACCAG-3′; tcf21-124F2 5′-TCTCCACTCCACCCTTGT CTC-3′; and tcf21-805R2T7 5′-GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGATGCGAGTGAGGATGTTGTCC-3′. The primers used for left1 (875 bp) were: lefty1-83F1 5′-ACGCTCTGCTGAAGAAACTGG-3′; lefty1-1065R2 5′-AATATTGTCCATTGCGCATCC-3′; lefty1-153F2 5′-GATCCCAACGCACGTAAAGAA-3′; and lefty1-1027R2T7 5′-GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTGTTTGGGAATTCAGCCACTT-3′. Primers for lefty2 (807 bp) were: lefty2-31F1 5′-ACCACAGCGATCTCACTCACA-3; lefty2-1029R1 5′-TTCTGCCACCTCGATTTCAGT-3′; lefty2-35F2 5′-CAGCGATCTCACTCACACAGG-3′; and lefty2-841R2T7 5′-GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTGAGCTCACGGAAGTTGATGA-3′. For spaw (656 bp), we used the following primers: spaw-210F1 5′-TAGTGTTGACAACCCGGCTCT-3′; spaw-1200R1 5′-CTCCTCCACGATCATGTCCTC-3′; spaw-461F2 5′-AACTGTTTCTGGGCAGCGTTA-3′; and spaw-1116R2T7 5′-GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCACCACTCCATCCCCTTCATA-3′. The primers for bmp4 (851 bp) were: bmp4-76F1 5′-CTGATACCCGAGGAAGGGAAG-3′; bmp4-1068R1 5′-CACCGAGTTCACCAGTGTCTG-3′; bmp4-84F2 5′-CGAGGAAGGGAAGAAGAAAGC-3′; and bmp4-934R2T7 5′-GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCGTCGCTGAAATCCACATACA-3′. For myl7 (440 bp), we used: myl7-25F1 5′-AAGAGGGGGGAAACTGCTCAA-3′; myl7-518R1 5′-CAAGATTCCTCTTTTTCATCACCA-3′; myl7-27F2 GAGGGGGAAAACTGCTCAAAG-3′; and myl7-466R2T7 GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGAATCAATATTTCCAGCCACGTC. The following primers were used for amhc (939 bp): amhc-4486F1 5′-AGGCTCGCAGTTTAAGCACTG-3′; amhc-5651R1 5′-CAAATTCTTGCGATCCTCGTC-3′; amhc-4614F2 5′-GTAAGCGAAGGGCGAAAGAGT-3′; and amhc-5552R2T7 5′-GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGAGCGTCCAGCTCATTCTCAAG-3′. Primers for vmhc (903 bp) were: vmhc-3141F1 5′-GGCAAAAGCAAAGCTAGAGCA-3′; vmhc-4276R1 5′-CGGTTTCCTGTAAGCGTTGAG-3′; vmhc-3258F2 5′-AACCCAGGAAAGCCTAATGGA-3′; and vmhc-4160R2T7 5′-GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGACATGCCTCGCTGTAGCTCT-3′.

All digoxigenin-UTP-labeled anti-sense RNA probes were synthesized using DIG-RNA (Sigma-Aldrich) labeling mix and T7 RNA polymerase (PCR DNA templates for wt1a, tcf21, bmp4, lefty1, lefty2, spaw, cmlc2, amhc, vmhc and nppa) or SP6 RNA polymerase (plasmid templates for wtip and tbx18; New England BioLabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to localize the probes (50). NBT/BCIP (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the chromogenic substrate to produce blue precipitate. The zebrafish tbx18 DNA template was subcloned to pCR-BluntII-TOPO vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Primers used to prepare DNA template for RT-PCR and 2nd PCR for tbx18 (828 bp) were as follows: tbx18-14F1 5′-GACGGTCCCCGTGTACTATGA-3′; tbx18-997R1 5′-TCCCAAGGATGTCCTCAAATG-3′; tbx18-91F2 5′-AAATTGGAGGAGGAGGACAGC-3′; and tbx18-918R2 5′-CATTCTGTTTCGTCCCGAGTC-3′. Finally, tbx18 plasmid was linearized by XhoI and SP6 RNA polymerase, and wtip plasmid was linearized by NotI and SP6 RNA polymerase (44).

Cardiac looping assessments

The extent of cardiac looping was assessed in wtip morphants and buffer-injected control embryos using the Tg(myl7:EGFP) line. At 48 hpf, embryos were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, mounted in 1% agarose and were optimally positioned for cardiac imaging. The looping angle (LA) was defined as the angle between the anterior/posterior axis of the embryo and the cross-sectional plane of the AV junction (55). Student's t-test using an α of 0.05 was used to evaluate differences in looping angle means (n=10 hearts/treatment). Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Antibodies and whole-mount immunohistochemistry

A previously published protocol was followed (44,56). Primary antibodies were: Custom-made anti-Wtip (1:100 dilution; Covance, Inc., Denver, PA, USA), anti-γ-tubulin (GTU-88; 1:800 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-acetylated α-tubulin (6-11B-1; 1:800 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-centrin (20H5; 1:1,000 dilution; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The following secondary antibodies were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.: Goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor®546 (IgG [H+L]), goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor®488 (IgG2b), goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor®488 [IgG1 (γ1)], goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor®488 [IgG2a (γ2a)] and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor®546 [IgG1 (γ1)]. Whole-mount immunohistochemistry samples were dehydrated with a graded series of methanol, embedded in JB4 resin (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA, USA), and were cut into 5–7 µm sections using an RN2255 microtome (Leica Technology, Exton, PA, USA). The sections were stained with DAPI (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA), mounted in Fluorescent Mounting Media (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc.), and were imaged with a FV-1000 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus America, Inc., Center Valley, PA, USA).

Histological analysis

Embryos were fixed with histology fixative [1.5% glutaraldehyde, 4% formaldehyde, 3% sucrose in 0.1 mM phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.3)] overnight at 4°C. Fixed embryos were then dehydrated with a graded series of methanol and embedded in JB4 resin (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA, USA). Sections (4 µm) were cut with an RN2255 microtome (Leica Technology) and were stained with Harris hematoxylin and special eosin II (BBC Biochemical, Mount Vernon, WA, USA). Once the sections were mounted in Polymount (Polysciences, Inc.), the stained sections were imaged with a Provis AX-70 microscope (Olympus America, Inc.) equipped with a RETIGA EXi digital camera (QImaging, Surrey, Canada).

Results

Wtip expression in the cardiac region is identical to PE marker genes

WT1 is expressed in the PE and glomerulus podocytes in mammals, birds, zebrafish and medaka (22,57–61). In addition to wt1a gene expression in zebrafish PE (22), the expression patterns of other PE markers, including tcf21 and tbx18, are well documented at 48 hpf, 57 hpf, and 4 days post-fertilization (dpf) (22,23). It was previously demonstrated that zebrafish embryos depleted for wtip via anti-sense morpholino (wtipMO) developed pericardial edema (44).

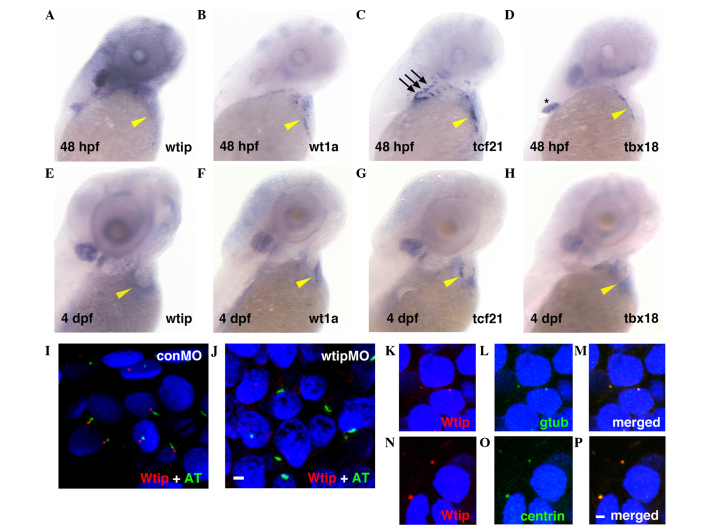

To investigate possible roles for Wtip in PE specification and development, whole-mount in situ hybridization was used (Fig. 1). Wtip mRNA was detected at 48 hpf (Fig. 1A) and 4 dpf (Fig. 1E) in zebrafish embryonic hearts. At 48 hpf, wtip-positive cells at the pericardial surface of the yolk were observed to be broadly dispersed at the AV-to-sinus venous region (Fig. 1A, yellow arrowhead marks the AV junction). By 4 dpf, wtip-positive cells appeared to have spread over the heart to cover the myocardium (Fig. 1E, yellow arrowhead). To determine the identity of the cells expressing wtip, the common PE marker genes wt1a (Fig. 1B and F, yellow arrowheads), tcf21 (Fig. 1C and G, yellow arrowheads) and tbx18 (Fig. 1D and H, yellow arrowheads) were evaluated at 48 hpf (Fig. 1A–D) and 4 dpf (Fig. 1E–H). At 48 hpf, wt1a, tcf21 and tbx18 expression was detected at the level of the sinus venous and adjacent to the AV junction (Fig. 1B–D, yellow arrowheads). At this stage, cardiac expression typically appears punctate, as would be expected for the isolated clumps of PE, which have not yet formed a uniform layer. In addition, tcf21 expression occurred in the pharyngeal arch (Fig. 1C, black arrows), and tbx18 expression occurred in the pectoral fin (Fig. 1D, asterisk). By 4 dpf, the wt1a-, tcf21- and tbx18-positive cells spread over the heart to cover the myocardium (Fig. 1F–H, yellow arrowheads). Therefore, the wtip-positive cells exhibited an expression pattern similar to the known PE marker genes wt1a, tcf21 and tbx18, and corresponded in physical appearance to extracardiac cell populations, indicating their PE identity (22,23).

Figure 1.

wtip expression is identical to PE-specific markers during zebrafish heart development. Lateral view of (A–D) 48 hpf and (E–H) 4 dpf whole-mount in situ hybridization of (A,E) wtip, (B,F) wt1a, (C,G) tcf21 and (D,H) tbx18. At 48 hpf, (A) wtip, and PE markers (B) wt1a-, (C) tcf21- and (D) tbx18- positive cells were in the clusters near the sinus venosus, between the atrium and the yolk and near the AV junction, in contact with the ventral surface of the heart (yellow arrowhead in A–D). At 48 hpf, tcf21 expression occurred in the pharyngeal arch (black arrows in C) and tbx18 expression occurred in the pectoral fin (black asterisk in D). By 4 dpf, the wt1a-, tcf21- and tbx18-positive cells spread over the heart to cover the myocardium (yellow arrowhead in F–H). By 4 dpf, wtip-, tcf21- and tbx18-positive cells appeared to spread over the heart to cover the myocardium along the dorsal surface of the heart (yellow arrowhead in E–H). (I,J) Double immunofluorescence for the cilia marker acetylated α-tubulin (green) and Wtip (red) in confocal projections of the zebrafish PE at 48 hpf. (J) No Wtip signal was detectable in wtipMO knockdown embryos, confirming antibody specificity. (K–P, red) Localization of Wtip in the basal bodies of cilia was confirmed by double immunostaining with Wtip antibody and either (L,M, green) anti-γ-tubulin or (O,P, green) anti-centrin, which are basal body markers in heart. 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole was used to counterstain nuclei (blue). Scale bar=10 µm. wtip, Wilms tumor 1 interacting protein; PE, proepicardial organ; hpf, hours post-fertilization; dpf, days post fertilization; wt1a, Wilms tumor 1a; tcf21, transcription factor 21; tbx18, Tbox 18; wtipMO, wtip morpholino oligonucleotide; conMO, control MO; AT, acetylated α-tubulin.

To further assess a possible cell autonomous role for Wtip in the PE, the subcellular localization of this protein in the PE was examined using a zebrafish-specific anti-Wtip antibody (44). In a previous study, Wtip protein was observed to be enriched in the basal body, a structure that resides at the base of cilia in the pronephros, Kupffer's vesicle (KV) and other ciliated tissues (44). While cilia have not been reported in the zebrafish embryonic heart, they have been discovered in mouse (39) and chick hearts (62). Accordingly, the possibility that Wtip may localize to the basal body at the base of cilia in the zebrafish embryonic heart was considered. Therefore, double immunostaining was performed with antibodies against zebrafish Wtip and the cilia marker acetylated α-tubulin (Fig. 1I and J), or the basal body marker γ-tubulin (Fig. 1K–M) and basal body marker centrin (Fig. 1N–P), in 48 hpf PE. Sagittal section staining suggested that Wtip was localized to the basal body of cilia located on PE in the 48 hpf embryos (Fig. 1I–P). The specificity of the localization pattern was verified by knockdown of endogenous wtip expression with wtipMO (44), which abolished Wtip immunostaining (Fig. 1J). Together, these data provide the first evidence, to the best of our knowledge, that the zebrafish embryonic heart develops cilia and basal bodies (Fig. 1I–P). In addition, these data indicate that Wtip is expressed in the basal bodies of cells in the PE of the zebrafish embryonic heart.

Wtip signaling is required for PE specification

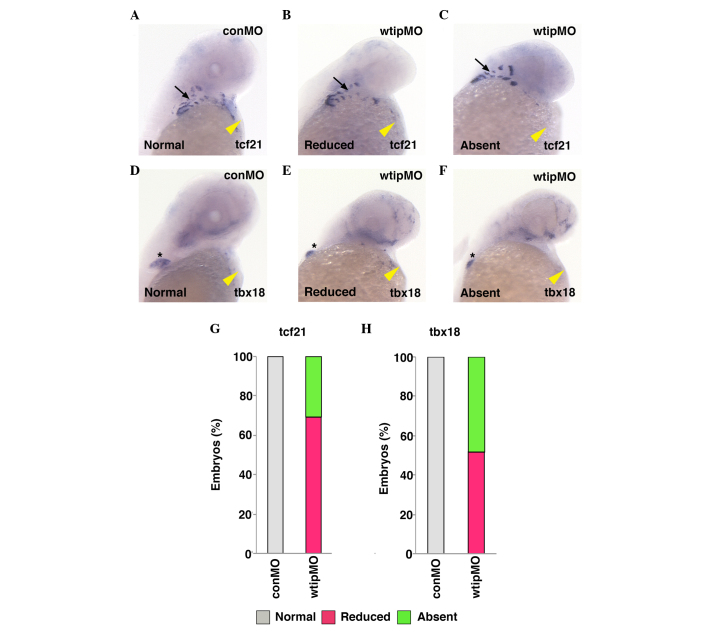

wt1 null mutant mice develop cardiac abnormalities (16), and the epicardium fails to form properly (19). The wt1 gene is expressed in both the epicardial lineage and in kidney podocytes, and this pattern is well conserved in mammals, zebrafish and medaka (22,59,61,63). To test whether Wtip is required for PE formation and specification during zebrafish embryonic heart development, a wtip morpholino antisense oligonucleotide (MO) was used to inhibit translation of wtip transcripts (44). First, the PE formation in 48 hpf wtip knockdown embryos was examined (Fig. 2) using the PE-specific markers tcf21 (Fig. 2B, C and G) and tbx18 (Fig. 2E, F and H). Injection of wtipMO produced embryos with body axis curvature, pronephric cysts, hydrocephalus and pericardial edema. Approximately 99% of injected embryos (n=64) developed pericardial edema. In wtip knockdown embryos, the expression of tcf21 and tbx18 in the heart was found to be significantly reduced (25/36, 69.4% for tcf21 and 14/27, 51.9% for tbx18; Fig. 2B, E, G and H, yellow arrowheads) or absent (11/36, 30.6% for tcf21 and 13/27, 48.1% for tbx18; Fig. 2C, F, G and H, yellow arrowheads). By contrast, despite modest developmental delay (2 h) in these embryos, tcf21 expression in the pharyngeal arch (Fig. 2B and C, black arrows) and tbx18 expression in the pectoral fin were unaffected (Fig. 2E and F, asterisk). These data indicate that Wtip signaling is essential for early epicardial development and is required to specify the PE.

Figure 2.

Wtip is required for PE specification. Ventral view of 48 hpf whole-mount in situ hybridization of (A–C) tcf21 and (D–F) tbx18 in (A,D,G,H)control (1.035 pmol/embryo) and (B,C,E–H) wtip morphant embryos (1.035 pmol/embryo). Both tcf21 and tbx18 express specifically in the PE in the control embryos (yellow arrowhead in A, D), but is reduced or absent in wtip morphant embryos. tcf21 expression in the pharyngeal arch (black arrow in A–C) and tbx18 expression in the pectoral fin (black asterisk in D–F) in wtip morphants are unaffected. wtip, Wilms tumor 1 interacting protein; PE, proepicardial organ; hpf, hours post fertilization; tcf21, transcription factor 21; tbx18, Tbox 18; conMO, control morpholino oligonucleotide.

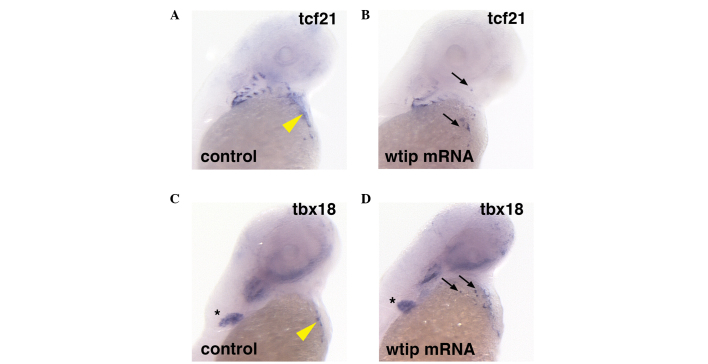

To determine whether Wtip signaling is sufficient to induce PE marker gene expression, wtip mRNA was overexpressed (Fig. 3). In embryos with ubiquitous wtip mRNA expression, ectopic tcf21 (34/34, 100%; Fig. 3B, black arrows) and tbx18 (31/31, 100%) expression was observed in the heart region (Fig. 3D, black arrows) compared with control tcf21 (n=26; Fig. 3A) and tbx18 (n=26; Fig. 3C) expression in the PE region of the heart (yellow arrowheads indicate sinus venous). In all of the wtip mRNA-overexpressing embryos, ectopic clusters of the tcf21- and tbx18-positive cells were observed, which appeared more widespread and numerous than the clusters seen in wild-type embryos. Occasional ectopic clusters were located in or near the craniofacial area (Fig. 3B and D, black arrows), and were consistently observed in the cardiac region. Overexpression of wtip mRNA in embryos did not affect tbx18 expression in the pectoral fin (Fig. 3C and D, black asterisk).

Figure 3.

Ectopic expression of tcf21 and tbx18 in the cardiac and pharyngeal arch regions by wtip mRNA overexpression. Ventral view of 48 hpf whole-mount in situ hybridization of (A,B) tcf21 and (C,D) tbx18) in (A,C) control and (B.D) wtip mRNA-injected embryos (92 pg/embryo). The ectopic expression of tcf21 (black arrows in B) and tbx18 (black arrows in D) expression in the heart region compared with control tcf21 (yellow arrowhead in A) and tbx18 (yellow arrowhead in C) expression in the PE region of the heart. tbx18 expression in the pectoral fin (black asterisk in C) was unaffected in wtip mRNA-injected embryos. tcf21, transcription factor 21; tbx18, Tbox 18; wtip, Wilm's tumor 1 interating protein; hpf, hours post fertilization; PE, proepicardial organ.

Wtip and wt1a functionally interact during PE development

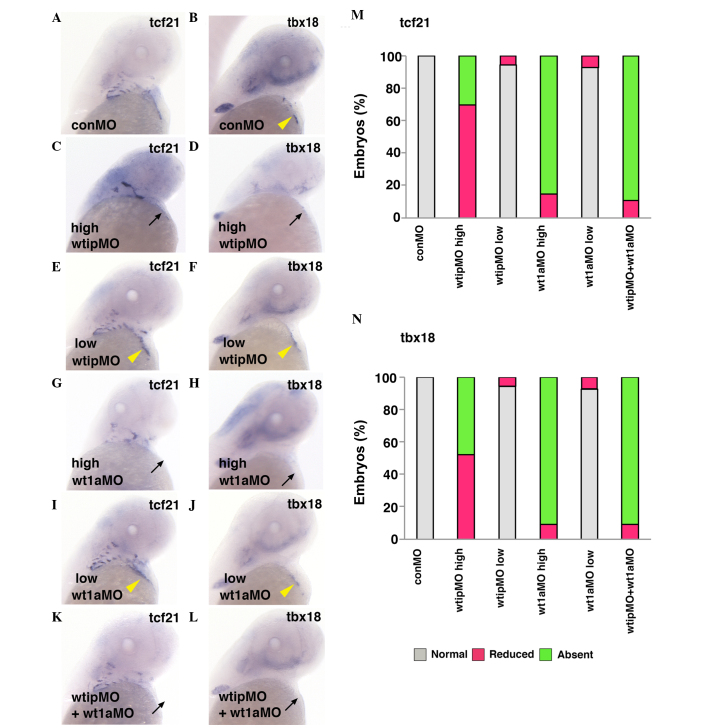

Mouse wtip was originally identified as an interacting partner of wt1 in a yeast two-hybrid screen (40). However, the implications of the potential interation between Wtip and WT1 in PE formation have not been reported. The co-expression of wt1a (Fig. 1B and F, yellow arrowhead; 22) and wtip (Fig. 1A and E, yellow arrowhead) in PE control embryos, along with the similar cardiac phenotypes generated by knockdown of either gene, support the notion that these two genes may function together in zebrafish PE formation. In wt1a morphants (Fig. 4), the expression of PE markers was reduced (7/47, 14.9% for tcf21, Fig. 4M; and 3/33, 9.1% for tbx18; Fig. 4N) or absent (40/47, 85.1% for tcf21, Fig. 4G and M, black arrows; and 30/33, 90.9% for tbx18; Fig. 4M and N, black arrows). As described (Fig. 2B, C, E–H), in wtip morphants, PE markers were similarly reduced (21/30, 70% for tcf21, Fig. 4M; and 13/25, 52% for tbx18, Fig. 4N) or absent (9/30, 30% for tcf21, Fig. 4C and M, black arrow; and 12/25, 48% for tbx18, Fig. 4D, and N, black arrow). To further investigate the potential for Wtip and WT1 interaction, a combined knockdown of wtip and wt1a was performed using sub-threshold doses of both morpholinos to assess whether a genetic interaction between these proteins would alter the expression of the PE markers tcf21 and tbx18. Prior to this, the appropriate sub-threshold doses for each morpholino was determined: i) wt1aMO, n=28 for tcf21 (Fig. 4I and M, yellow arrowhead) and n=27 for tbx18 (Fig. 4J and M, yellow arrowhead) and ii) wtipMO, n=36 for tcf21 (Fig. 4E and M, yellow arrowhead) and n=35 for tbx18 (Fig. 4F and M, yellow arrowhead). Sub-threshold doses for either morpholino alone had no effect on tcf21 (Fig. 4E, I and M, yellow arrowhead) or tbx18 (Fig. 4F, J and N, yellow arrowhead) expression in the PE: wt1aMO, 26/28, 92.9% for tcf21 (Fig. 4I and M, yellow arrowhead) and 25/27, 92.6% for tbx18 (Fig. 4J and N, yellow arrowhead); wtipMO, 34/36, 92.9% for tcf21 and 33/35, 94.3% for tbx18 (Fig. 4E, F, M and N, yellow arrowhead). However, in wtip and wt1a double morphants, tcf21 and tbx18 expression was severely reduced (3/27, 11.1% for tcf21, Fig. 4M; and 3/32, 9.4% for tbx18, Fig. 4N) or absent (24/32, 88.9% for tcf21, Fig. 4K and M, black arrow; and 29/32, 90.5% for tbx18, Fig. 4L and N, black arrow) in the cardiac region. These data indicate that Wtip is genetically associated with Wt1a, and that together they influence PE specification.

Figure 4.

Wt1a and Wtip cooperate for PE formation. Ventral view of 48 hpf whole-mount in situ hybridization of (A,C,E,G,I,K) tcf21 and (B,D,F,H,J,L) tbx18 expression in control (yellow arrowhead, A,B), high concentration of wtipMO (black arrow, C,D; 1.035 pmol/embryo), sub-threshold concentration of wtipMO (yellow arrowhead, E,F; 0.259 pmol/embryo), high concentration of wt1aMO (black arrow, G,H; 1.15 pmol/embryo), sub-threshold concentration of wt1aMO (yellow arrowhead, I,J; wt1aMO, 0.288 pmol/embryo), sub-threshold concentrations of wt1aMO (1.15 pmol/embryo)+wtipMO (0.259 pmol/embryo; black arrow, K,L) in PE at 48 hpf. With high concentrations of wt1aMO, PE marker expressions were reduced or absent (black arrow, for tcf21; G,M, and for tbx18; H,N). With wtipMO, PE marker expressions were reduced (for tcf21, M and for tbx18, N) or absent (black arrow, for tcf21; C,M, and for tbx18; D,N). Sub-threshold doses for each MO had no effect on tcf21 (yellow arrowhead, E,I,M) or tbx18 (yellow arrowhead, F,J,N) expression in PE. In the wtip and wt1a double morphants, tcf21 and tbx18 were severely reduced (black arrow, for tcf21; K,M and for tbx18; L,N) or no longer expressed (for tcf21 and for tbx18) in the cardiac region. These data indicate that Wtip is associated with Wt1a and influences PE specification. Wt1a, Wilm's tumor 1a; Wtip, Wilm's tumor 1 interacting protein; PR, proepicardial organ; hpf, hours post fertilization; tcf21, transcription factor 21; tbx18, Tbox 18; wtipMO, wtip morpholino oligonucleotide.

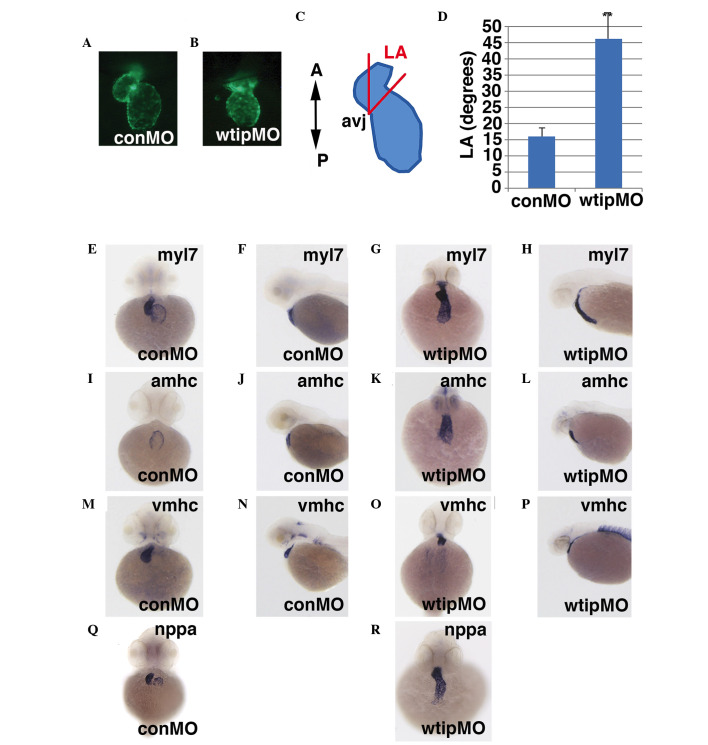

Wtip is required for cardiac looping and valve formation, but not for chamber patterning

Cardiac looping is a morphogenic process in vertebrates. This process re-shapes the linear heart tube by bending the cardiac chambers into close juxtaposition. In zebrafish, cardiac looping begins around 30 hpf as the heart tube folds, gradually bringing the atrium and ventricle into a side-by-side position by 48 hpf (15,37). The continued bending of the heart tube, accompanied by chamber ballooning (~48–58 hpf) (64), and concentric growth within the chambers (65), substantially remodels the shape of the heart by 72 hpf. Functionally, the organ changes rapidly over this period, as heart rate and cardiac output increase steadily (3,66,67). Blood flow, which initially incorporates some back-flow through the AV junction, becomes consistently unidirectional as endocardial cushions and AV valves develop (68). Transgenic Tg(myl7:EGFP) embryos, which express GFP in the embryonic heart, provided easy visualization of the heart (Fig. 5A and B). As a simple rubric to describe the progression of cardiac looping in wtip morphants, the cardiac 'looping angle' was measured, defined as the degree of difference in the anterior/posterior (A/P) body axis and the plane of the AV junction (Fig. 5C) (55). At 48 hpf, control hearts exhibited an average looping angle of 16°, whereas looping angles in embryos injected with wtipMO were significantly larger, indicating that they were less looped (Fig. 5A–D). These data indicate that cardiac looping was impaired by Wtip depletion.

Figure 5.

Wtip is required for AV boundary formation, but does not affect chamber patterning. Hearts of transgenic Tg(myl7:EGFP) embryos were visualized in 48 hpf (A) control or (B) wtip morphant embryos (1.035 pmol/embryo) to assess the extent of cardiac looping. (C) Diagram depicting the cardiac LA, defined as the degree of difference in the anterior/posterior body axis and the plane of the AV junction. (D) Wtip depletion decreases the mean LA by 48 hpf. The mean ± standard error is shown. *P<0.000359. n=10 embryos/treatment. 48 hpf whole-mount in situ hybridization in (E,F,I,J,M,N,Q) control and (G,H,K,L,O,P,L) wtip morphant embryos (1.035 pmol/embryo) of (E–H) myl7, (I–L) amhc, (M–P) vmhc and (Q,R) nppa. (E,G,I,K,M,O,Q,R) Ventral view and (F,H,J,L,N,P) lateral view. Wtip does not regulate chamber patterning, but regulates nppa expression to maintain chamber myocardium expression and exclusion from the myocardium of the AV boundary. Wtip, Wilm's tumor 1 interacting protein; AV, atrioventricular; myl7, myosin light chain 7; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; hpf, hours post fertilization; LA, looping angle; amhc, α myosin heavy chain; vmhc, ventricular myosin heavy chain; nppa, natriuretic peptide A; conMO, control morpholino oligonucleotide; A, anterior; P, posterios; avj, AV junction.

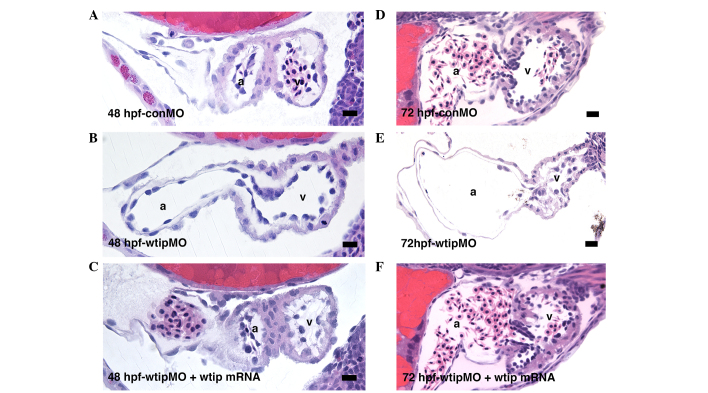

Next, it was examined whether the cardiac looping defect of wtip morphants was due to improper establishment of cardiac patterning. At 48 hpf, wtip morphants showed normal expression of the cardiac chamber-specific markers myl7 (cmlc2) (Fig. 5E–H), amhc (Fig. 5I–L) and vmhc (Fig. 5M–P). By 48 hpf, hearts in wild-type embryos have initiated cardiac looping, which shifts the ventricle to the right of the atrium (Fig. 5E, I and M). In the process of checking the heart patterning, a role for Wtip in differentiating the AV boundary was identified. At 52 hpf, nppa was detected in both the ventricle and atrium but was absent from the AV boundary in wild-type embryos (Fig. 5Q, black arrows). Conversely, nppa was detected throughout the heart, with no distinguishable exclusion from the AV boundary in wtip knockdown embryos (Fig. 5R). Analysis of sections (Fig. 6) revealed a thinned myocardial layer in the atrium, and increased separation of the myocardium and endocardium in the ventricle (Fig. 6B and E). Rather than transitioning to the expected cuboidal shape, AV endocardial cells in wtip knockdown embryos retained a squamous appearance at 72 hpf, and clear leaflets did not form (Fig. 6E). Importantly, the lack of AV boundary, thinned myocardial layer in the atrium, and increased separation of the myocardium and endocardium in the ventricle phenotype of wtip morphants could all be rescued by the co-injection of wtip mRNA, demonstrating that the phenotypes specifically result from wtip knockdown (Fig. 6C and F).

Figure 6.

Wtip is required for proper valve development. Sagittal histological section of (A–C) 48 hpf and (D–F) 72 hpf zebrafish embryo hearts. (B,E) wtip morphants (1.035 pmol/embryo) display pericardial edema and (C,F) wtip mRNA (92 pg/embryo) can rescue pericardial edema. Scale bar=10 µm. Wtip, Wilm's tumor 1 interacting protein; hpf, hours post fertilization; conMO, control morpholino oligonucleotide.

Knockdown of wtip results LR asymmetry defects

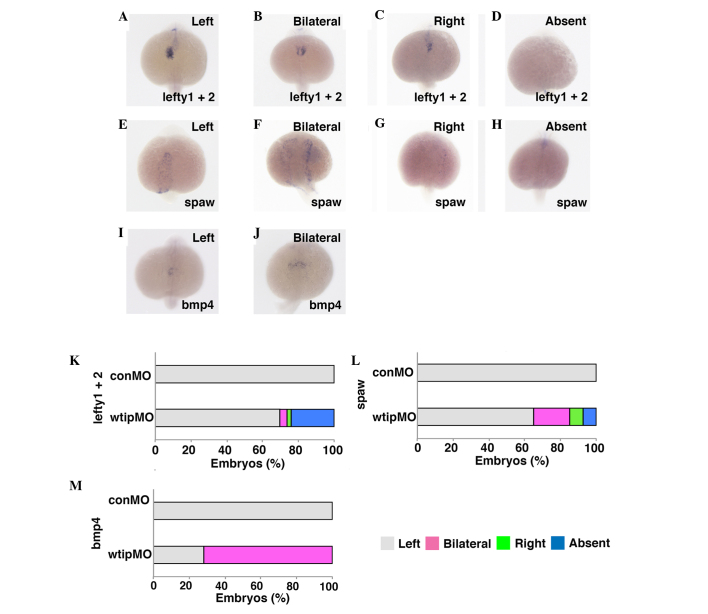

Ajuba LIM proteins (LIMD1, WTIP, AJUBA) are categorized as a family of LIM domain proteins, however, their functional similarities remain unclear. Embryos depleted for the Ajuba homolog in medaka (69) and zebrafish (70) exhibited developmental abnormalities, including LR patterning defects. It has been previously shown by in situ hybridization that wtip is expressed in a broad range of tissues during the gastrula period and early somitogenesis (44), including KV, which is equivalent to the mammalian node in teleosts (71–73). Furthermore, Wtip protein expression was investigated by immunostaining using a zebrafish-specific Wtip antibody, which localized to the basal bodies of pronephros, KV and ciliated tissues (44). The wild-type heart typically 'jogs' to the left and subsequently loops to the right (34). To investigate the establishment of the LR axis within the forming zebrafish heart tube, bmp4 expression was examined (Fig. 7), which is normally expressed predominantly on the left side of the cardiac cone (118/118, 100%; Fig. 7I and M) (34). It was observed that wtip depletion caused embryos to exhibit bilateral bmp4 expression (85/118, 72%; Fig. 7J and M). The heart tube of wtip morphants never underwent looping as occurred in control embryos at 48 hpf, which may reflect altered left-right patterning of the body (Fig. 5A–D, G, K, O and R). Next, it was checked whether Wtip regulates not only bmp4, but also other early LR asymmetry markers in zebrafish. The left1/2 and southpaw (spaw) genes encode TGF-β superfamily proteins that are expressed in the left lateral plate mesoderm in wild-type embryos. These early laterality markers are essential for the establishment of LR asymmetry in zebrafish (53). To investigate whether Wtip regulates zebrafish LR patterning by modulating the formation and/or function of KV, wtipMO was injected into the yolk at the early blastula stage (128-cell stage) to target the precursors of KV (DFCs) and left1/2 (Fig. 7A–D, K) and spaw (Fig. 7E–H, L) expression patterns were examined. Injection of wtipMO led to randomization of the LR axis, as shown by left1/2 (Fig. 7A–D, K) and spaw (Fig. 7E–H, L) gene expression in the lateral plate mesoderm at 20 hpf. All control embryos displayed a left-sided left1/2 (118/118, 100%) and spaw (180/180, 100%) expression (Fig. 7A, E, K and L). By contrast, wtip morphants exhibited the full range of possible expression patterns: Left-sided expression (left1/2, 111/159, 69.8%; spaw, 120/185, 64.9%), bilateral expression (left1/2, 6/159, 3.8%; spaw, 37/185, 20%), right-sided expression (left1/2, 4/159, 2.5%; spaw, 14/185, 7.5%), and no expression (left1/2, 38/159, 23.9%; spaw, 14/185, 7.5%; Fig. 7A–H, K and L). These data suggest that Wtip signaling is required for early LR asymmetry.

Figure 7.

Wtip is required for early left-right patterning. Dorsal views, anterior to the bottom of the panels. (A–D,K) lefty1 and lefty2, (E–H,L) spaw and (I,J,M) bmp4 expressions in (A–J) 22-somite stage embryos. Normally, (A,E,I) left1+2, spaw and bmp4 transcripts expressed in the left cardiac lateral plate mesoderm, (B,F,J) have bilateral, (C,G) right and (D,H) absent expression in wtip morphants (1.035 pmol/embryo). Bar chart details the left-right patterning for control and wtip morphants. Wtip, Wilm's tumor 1 interacting protein; lefty1, left right determination factor 1; spaw, southpaw; bmp4, bone morphogenic factor 4; conMO, control morpholino oligonucleotide.

Discussion

In humans, a wide range of cardiovascular defects is associated with kidney cystic disease, although the etiology of these abnormalities remains unclear. Similar to humans, pericardial edema in zebrafish is often observed in kidney cystic mutants or MO-mediated knockdown embryos (74,75). However, the specific roles of cilia and basal bodies in PE, heart morphogenesis and function during normal development, and congenital heart disease (CHD) remain unknown (37,76). Compared to myocardium and endocardium, relatively little is known about how PE develops and differentiates. The PE is an extra-cardiac source for several cardiac cell types, and increasing evidence suggests that the PE plays a role in heart development, repair of cardiac injury and ingrowth of coronary vessels (5–12). Despite the potentially central role of the epicardium in all of these processes, the molecular signals driving the specification and morphogenesis of PE remain poorly understood. In the present study, the role of Wtip in PE development was investigated and genetic evidence presented that WT1, in association with Wtip, is required for PE specification. We further revealed a critical role for Wtip in heart looping and the establishment of the AV boundary. Based on the expression pattern of wtip mRNA and protein, blocked Wtip function, and wtip over-expression data, it is proposed that Wtip is required at early somite stages to provide LR asymmetry, and independently regulates later cardiac development, including heart-looping, PE specification and differentiation of the AV boundary.

Wtip was originally identified as an interacting partner of WT1 in a yeast two-hybrid screen (40). WT1 is expressed in the PE and glomerulus podocytes in mammals, birds, zebrafish and medaka (22,57–61). It was previously reported that depletion of the Wtip basal body was associated with the development of pronephric cysts, with it noted that these embryos also developed pericardial edema (44). Previously, cryptic deletion in the human wtip gene was reported to cause hypospadias (urethra malformation in males) that can be associated with congenital heart disease (45). Therefore, we predicted that pericardial edema in wtip knockdown embryos may be due to PE defects.

In the present study, a critical role of Wtip in PE specification during heart development was identified. It was demonstrated that wtip shows cardiac expression in PE at 48 hpf and 4 dpf, in a pattern that specifically matches that of known PE-specific genes wt1a, tcf21, and tbx18 (22,23). Additionally, it was confirmed that the PE contains ciliated cells, and that Wtip localizes to the basal bodies within these cells in 48 hpf embryos, as was the case for ciliated cells in the pronephros and Kupffer's vesicle (44). This is the first evidence that the zebrafish embryonic heart develops cilia and basal bodies during embryonic development. Furthermore, it was observed that depletion of wtip leads to the severe reduction or absence of PE formation and that Wtip and wt1a cooperate for PE formation. By overexpressing wtip mRNA, ectopic expression of PE-specific markers was observed in the cardiac region and in the pharyngeal arch area. Based on wtip gene and protein expression patterns and on phenotypes generated by blocking Wtip function, it is proposed that Wtip is required initially to establish early LR asymmetry, and later to form the PE, modulate heart looping and promote AV differentiation.

Recently, the PE has been investigated for its role in normal heart morphogenesis (13,15,77) and additional capacity to form coronary vascular endothelial cells in mice (20). Zebrafish are now well established as a key model system for embryonic heart development and function, and possess a natural capacity for adult myocardial regeneration (78). To directly examine the possible critical roles for Wtip or the PE in response to injury and myocardial regeneration in adults, we would need to further consider using wt1a, tcf21 or tbx18 transgenic lines (24–26).

A previous study reported that cells with primary 9+0 cilia were found in both the embryonic and the adult human heart (79). Previous studies revealed that monocilia are found in the mouse embryonic heart at embryonic day (e) e9.5–e12.5, by which time blood flow is present (39,76). The data suggest that in zebrafish embryos, cilia occur in the PE by 48 hpf, a similar stage to what has been observed in the chick embryonic heart (62). Previous reports suggest that mice lacking cardiac cilia developed abnormal ECCs and compact myocardium (CM) at e9.5 (39,76). Notably, our observations in zebrafish suggest that wtip knockdown embryos lack a differentiated AV boundary, which is similar to the findings in mice, which lack ECCs (39,76). In addition, Wtip and cilia markers are co-expressed in the endocardium and myocardium prior to when the PE is formed in the zebrafish heart (data not shown), which may provide a connection to the AV valves that are simultaneously developing from the endocardium and myocardium. Previous studies have reported the timing and distribution of cilia in the embryonic mouse heart (39,76). At e9.5, cilia on the endocardial cells are predominantly located on the luminal surface, while cilia in the mesenchymal cells of the developing cushions are randomly oriented. By e12.5, atrial and ventricular septation is underway; only few cilia are found on the atrial endocardial layer. In the ECCs, however, cilia are found on the endothelial surface and are visible in the mesenchymal cells. The present study is the first, to the best of our knowledge, to report cilia on PE cells. Cilia in the endothelium may sense the flow during embryonic heart development. PE cells may be sensing information about their environment that relates to pericardial fluid or heartbeats, or potentially PE cilia may be involved in sensing biochemical information, such as the movement of fluid.

In mice, cilia are required for cardiac development, independently from their function in the development of LR asymmetry (39,76). Thus, it is possible that cardiac cilia function as mechanosensors, integrating information regarding flow, cardiac function and morphogenesis. If so, the prediction is that mutations in gene products that localize to cilia and/or basal bodies may affect heart morphogenesis and function. In zebrafish, many cystic mutant phenotypes accompany LR asymmetry defects originating in early somitogenesis stages, visible as altered spaw and left1/2 gene expression in the lateral plate mesoderm and by altered bmp4 expression in the zebrafish heart.

In control embryos, the progression of cardiac looping is a morphogenic process. The cardiac looping angle is defined as the degree of difference in the anterior/posterior (A/P) body axis and the plane of the AV boundary (55). The present study was unable to detect alterations in the expression of early patterning and chamber identity genes, suggesting that additional causes must be responsible for the malformation in the heart. Of note, chamber-specific markers amhc and vmhc were not altered, however, nppa was detected throughout the heart, with no distinguishable exclusion from the AV boundary in wtip knockdown embryos. Cardiac morphogenesis was significantly morphologically and molecularly affected at 48 and 72 hpf in wtip knockdown embryos, and gene restriction at the AV boundary was lost.

A number of the cardiac morphology mutants described in the original zebrafish large-scale mutagenesis screens have been well characterized, and the mutated genes have been identified. However, whether any of these mutants exhibit defects in cardiac cilia formation or function remains unknown, since the presence of cilia in the heart was not formerly described. Cardiac cilia are beginning to be characterized in other animal model systems, including chickens (62) and mice (39). As it was unknown whether basal bodies could affect heart morphogenesis and function, it was unclear whether heart defects could also be associated with early embryonic defects, such as LR patterning, which are thought to involve ciliary function.

The zebrafish system offers unique advantages for studying cell biology during vertebrate organogenesis, as zebrafish embryos develop externally and are practically transparent throughout early development, thereby allowing non-invasive observation. Previous studies in zebrafish indicate that endocardial cells in the AV differentiate before the onset of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation, thereby defining a previously unappreciated step during AV valve formation (80,81). New zebrafish mutants exhibiting AV valve development will provide a unique set of tools with which to further understand the genetic basis of PE cell behavior and its effect on heart development (80,81). Importantly, AV-associated phenotypes have been observed in mutant mouse models (81). The combination of genetics and pharmacological studies in animal models and the cell biology should provide novel insights into the developmental biology of cardiac organogenesis and provide relevant information to predict and understand human valvular and septal malformations.

The current study provides the first genetic evidence, to the best of our knowledge, for a novel role for the Wtip basal body protein in regulating the PE cell fate during development. In addition, our tools for wtip knockdown will be valuable for future studies to determine how Wtip signaling, possibly mediated via cilia, could indirectly modulate cardiac looping or AV development. The present study may additionally provide an avenue for understanding how the PE stimulates a response to cardiac injury, leading to its eventual repair.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all members of the Obara laboratory for the helpful discussion, and Kathy Kyler and Hiroyuki Matsumoto for critical reading of the manuscript. The authors would like to acknowledge the Zebrafish Information Resource Center for providing fish. Professor Tomoko Obara acknowledges financial support from the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (OUHSC). Professor Tomoko Obara was supported by NIH grants R21-DK069604 and R01-DK078209, and the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (OCAST) grant HR14-082. The present study is supported in part by the Diabetes Histology and Image Acquisition and Analysis Core Facility at OUHSC (NIH: COBRE-1P20RR024215).

References

- 1.DeHaan RL. Morphogenesis of the vertebrate heart. In: DeHaan RL, Ursprung H, editors. Organogenesis. Holt, Rinehart and Winston; New York: 1965. pp. 377–419. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serbedzija GN, Chen JN, Fishman MC. Regulation in the heart field of zebrafish. Development. 1998;125:1095–1101. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagatto B, Francl J, Liu B, Liu Q. Cadherin2 (N-cadherin) plays an essential role in zebrafish cardiovascular development. BMC Dev Biol. 2006;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fishman MC, Chien KR. Fashioning the vertebrate heart: Earliest embryonic decisions. Development. 1997;124:2099–2117. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.11.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mikawa T, Fishman DA. Retroviral analysis of cardiac morphogenesis: Discontinuous formation of coronary vessels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9504–9508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikawa T, Gourdie RG. Pericardial mesoderm generates a populations of coronary smooth muscle cells migrating into the heart along with ingrowth of the epicardial organ. Dev Biol. 1996;174:221–232. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dettman RW, Denetclaw W, Jr, Ordahl CP, Bristow J. Common epicardial origin of coronary vascular smooth muscle, perivascular fibroblasts, and intermyocardial fibroblasts in the avian heart. Dev Biol. 1998;193:169–181. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pérez-Pomares JM, Macías D, García-Garrido L, Munõz-Chápuli R. Immunolocalization of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 in the subepicardial mesenchyme of hamster embryos: Identification of the coronary vessel precursors. HIstochem J. 1998;30:627–634. doi: 10.1023/A:1003446105182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vrancken Peeters MP, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Mentink MM, Poelmann RE. Smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts of the coronary arteries derive from epithelial-mesenchymal transformation of the epicardium. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1999;199:367–378. doi: 10.1007/s004290050235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Vrancken Petters MP, Bergweff M, Mentink MM, Poelmann RE. Epicardial outgrowth inhibition leads to compensatory mesothelial outflow tract collar and abnormal cardiac septation and coronary formation. Cir Res. 2000;87:969–971. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reese DE, Mikawa T, Bader DM. Development of the coronary vessel system. Circ Res. 2002;91:761–768. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000038961.53759.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Gise A, Pu WT. Endocardial and epicardial to mesenchymal transitions in heart development and disease. Circ Res. 2012;110:1628–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.259960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manner J. Experimental study on the formation of the epicardium in chick embryos. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1993;187:281–289. doi: 10.1007/BF00195766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svensson EC. Deciphering the signals specifying the proepiardium. Cir Res. 2010;106:1789–1790. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.222216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakkers J. Zebrafish as a model to study cardiac development and human cardiac disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91:279–288. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreidberg JA, Sariola H, Loring JM, Maeda M, Pelletier J, Housman D, Jaenisch R. WT-1 is reqiored for early kidney development. Cell. 1993;74:679–691. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90515-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwee L, Baldwin HS, Shen HM, Stewart CL, Buck C, Buck CA, Laobow MA. Defective development of the embryonic and extraembryonic circulatory systems in vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1) deficient mice. Development. 1995;121:489–503. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang JT, Raybum H, Hynes RO. Cell adhesion events mediated by alpha 4 integrins are essential in placental and cardiac development. Development. 1995;121:549–560. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore AW, Mclnnes L, Kreidberg J, Hastie ND, Schedl A. YAC complementation shows a requirement for Wt1 in the development of epicardium, adrenal gland and throughout nephrogenesis. Development. 1999;126:1845–1857. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.9.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Red-Horse K, Ueno H, Weissman IL, Krasnow MA. Coronary arteries from by developmental reprogramming of venous cells. Nature. 2010;464:549–553. doi: 10.1038/nature08873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Gise A, Zhou B, Honor LB, Ma Q, Petryk A, Pu WT. WT1 regulates epicardial epithelial to mesenchymal transition through β-catenin and retinoic acid signaling pathways. Dev Biol. 2011;356:421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.05.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serluca FC. Development of the proepicardial organ in the zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2008;315:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J, Stainier DY. Tbx5 and Bmp signaling are essential for proepicardium specification in zebrafish. Circ Res. 2010;106:1818–1828. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lepilina A, Coon AN, Kikuchi K, Holdway JE, Roberts RW, Burns CG, Poss KD. A dynamic epicardial injury response supports progenitor cell activity during zebrafish heart regeneration. Cell. 2006;127:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kikuchi K, Gupta V, Wang J, Holdway JE, Wills AA, Fang Y, Poss KD. tcf21+ epicardial cells adopt non-myocardial fates during zebrafish heart development and regeneration. Development. 2011;138:2895–2902. doi: 10.1242/dev.067041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kikuchi K, Holdway JE, Major RJ, Blum N, Dahn RD, Begemann G, Poss KD. Retinoic acid production by endocardium and epicardium is an injury response essential for zebrafish heart regeneration. Dec Cell. 2011;20:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim J, Wu Q, Zhang Y, Wiens KM, Huan Y, Rubin N, Shimada H, Handin RI, Chao MY, Tuan TL, et al. PDGF signaling is required for epicardial function and blood vessel formation in regenerating zebrafish hearts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17206–17210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915016107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu H, Lee SH, Gao J, Liu X, Iruela-Arispe ML. Inactivation of erythropoietin leads to defects in cardiac morphogenesis. Development. 1999;126:3597–3605. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.16.3597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen TH, Chang TC, Kang JO, Choudhary B, Makita T, Tran CM, Burch JB, Eid H, Sucov HM. Epicardial induction of fetal cardiomyocyte proliferation via a retinoic acid-inducible trophic factor. Dev Biol. 2002;250:198–207. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sengbusch JK, He W, Pinco KA, Yang JT. Dual functions of [alpha]4[beta]1 integrin in epicardial development: Initial migration and long-term attachment. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:873–882. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatcher CJ, Diman NY, Kim MS, Pennisi D, Song Y, Goldstein MM, Mikawa T, Basson CT. A role for Tbx5 in proepicardial cell migration during cardiogenesis. Physiol Genomics. 2004;18:129–140. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00060.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlueter J, Brand T. A right-sided pathway involving FGF8/Snai1 controls asymmetric development of the proepicardium in the chick embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7485–7490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811944106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulte I, Schlueter J, Abu-Issa R, Brand T, Männer J. Morphological and molecular left-right asymmetries in the development of the proepicardium: A comparative analysis on mouse and chick embryos. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:684–695. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen JN, van Eeden FJ, Warren KS, Chin A, Nüsslein-Volhard C, Haffter P, Fishman MC. Left-right pattern of cardiac BMP4 may drive asymmetry of the heart in zebrafish. Development. 1997;124:4373–4382. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.21.4373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shu X, Huang J, Dong Y, Choi J, Langenbacher A, Chen JN. Na,K-ATPase alpha2 and Ncx4a regulate zebrafish left-right patterning. Development. 2007;134:1921–1930. doi: 10.1242/dev.02851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fakhro KA, Choi M, Ware SM, Belmont JW, Towbin JA, Lifton RP, Khokha MK, Brueckner M. Rare copy number variations in congenital heart disease patients identify unique genes in left-right patterning. Proc Natl Acad Sc USA. 2011;108:2915–2920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019645108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chin AJ, Saint-Jeannet JP, Lo CW. How insights from cardiovascular developmental biology have impacted the care of infants and children with congenital heart disease. Mech Dev. 2012;129:75–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Francis RJ, Christopher A, Devine WA, Ostrowski L, Lo C. Congenital heart disease and the specification of left-right asymmetry. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H2102–H2111. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01118.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slough J, Cooney L, Brueckner M. Monocilia in the embryonic mouse heart suggest a direct role for cilia in cardiac morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2304–2314. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Srichai MB, Konieczkowski M, Padiyar A, Konieczkowski DJ, Mukherjee A, Hayden PS, Kamat S, El-Meanawy MA, Khan S, Mundel P, et al. A WT1 co-regulator controls podocyte phenotype by shuttling between adhesion structures and nucleus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14398–14408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314155200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Wijk NV, Witte F, Feike AC, Schambony A, Birchmeier W, Mundlos S, Stricker S. The LIM domain protein Wtip interacts with the receptor tyrosine kinase Ror2 and inhibits canonical Wnt signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langer EM, Feng Y, Zhaoyuan H, Rauscher FJ, III, Kroll KL, Longmore GD. Ajuba LIM proteins are snail/slug corepressors required for neural crest development in Xenopus. Dev Cell. 2008;14:424–436. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Das Thakur M, Feng Y, Jagannathan R, Seppa MJ, Skeath JB, Longmore GD. Ajuba LIM proteins are negative regulators of the Hippo signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2010;20:657–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bubenshchikova E, Ichimura K, Fukuyo Y, Powell R, Hsu C, Morrical SO, Sedor JR, Sakai T, Obara T. Wtip and Vangl2 are required for mitotic spindle orientation and cloaca morphogenesis. Biol Open. 2012;1:588–596. doi: 10.1242/bio.20121016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gana S, Veggiotti P, Sciacca G, Fedeli C, Bersano A, Micieli G, Maghnie M, Ciccone R, Rossi E, Plunkett K, et al. 19q13.11 cryptic deletion: Description of two new cases and indication for a role of WTIP haploinsufficiency in hypospadias. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:852–856. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book A Guide For The Laboratory Use Of Zebrafish Danio (Brachydanio) Rerio. 4th edition. University of Oregon Pressm; Eugene, OR: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng J, Jia N, Han LN, Huang FS, Xie YF, Liu J, Tang JS. Microinjection of morphine into thalamic nucleus submedius depresses bee venom-induced inflammatory pain in the rat. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2008;60:1355–1363. doi: 10.1211/jpp.60.10.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amack JD, Yost HJ. The T box transcription factor no tail in ciliated controls zebrafish left-right asymmetry. Curr Biol. 2004;14:685–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hauptmann G, Gerster T. Multicolor whole-mount in situ hybridization. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;137:139–148. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-066-7:139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thisse C, Thisse B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:59–69. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yelon D, Home SA, Stainier DY. Restricted expression of cardiac myosin genes reveals regulated aspects of heart tube assembly in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 1999;214:23–37. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berdougo E, Coleman H, Lee DH, Stainier DY, Yelon D. Mutation of weak atrium/atrial myosin heavy chain disrupts atrial function and influences ventricular morphogenesis in zebrafish. Development. 2003;130:6121–6129. doi: 10.1242/dev.00838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Long S, Ahmad N, Rebagliati M. The zebrafish nodal-related gene southpaw is required for visceral and diencephalic left-right asymmetry. Development. 2003;130:2303–2316. doi: 10.1242/dev.00436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ahmad I, Pacheco M, Santos MA. Exzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants as an adaptaion to phagocyte-induced damage in Anguilla Anguilla L. following in situ harbor water exposure. Exotoxicol Environ Saf. 2004;57:290–302. doi: 10.1016/S0147-6513(03)00080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chernyavskaya Y, Ebert AM, Milligan E, Garrity DM. Voltage-gated calcium channel CACNB2 (β2.1) protein is required in the heart for control of cell proliferation and heart tube integrity. Dev Dyn. 2012;241:648–662. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim S, Zaghloul NA, Bubenshchikova E, Oh EC, Rankin S, Katsanis N, Obara T, Tsiokas L. Nde1-mediated inhibition of ciliogenesis affects cell cycle re-entry. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:351–360. doi: 10.1038/ncb2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pritchard-Jones K, Fleming S, Davison D, Bickmore W, Porteous D, Gosden C, Bard J, Buckler A, Pelletier J, Housman D, et al. The candidate Wilms' tumour gene is involved in genitourinary development. Nature. 1990;346:194–197. doi: 10.1038/346194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Armstrong JF, Pritchard-Jones K, Bickmore WA, Hastie ND, Bard JB. The expression of the Wilms' tumour gene, WT1, in the developing mammalian embryo. Mech Dev. 1993;40:85–97. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90090-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Drummond IA, Majumdar A, Hentschel H, Elger M, Solnica-Krezel L, Schier AF, Neuhauss SC, Stemple DL, Zwartkruis F, Rangini Z, et al. Early development of the zebrafish pronephros and analysis of mutations affecting pronephric function. Development. 1998;125:4655–4667. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carmona R, González-Iriarte M, Pérez-Pomares JM, Muñoz-Chápuli R. Localization of the Wilm's tumour protein WT1 in avian embryos. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;303:173–186. doi: 10.1007/s004410000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ichimura K, Bubenshchikova E, Powell R, Fukuyo Y, Nakamura T, Tran U, Oda S, Tanaka M, Wessely O, Kurihara H, et al. A comparative analysis of glomerulus development in the pronephros of medaka and zebrafish. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van der Heiden K, Groenendijk BC, Hierck BP, Hogers B, Koerten HK, Mommaas AM, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Poelmann RE. Monocilia on chicken embryonic endocardium in low shear stress areas. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:19–28. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perner B, Englert C, Bollig F. The Wilms tumor genes wt1a and wt1b control different steps during formation of the zebrafish pronephros. Dev Biol. 2007;309:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Auman HJ, Coleman H, Riley HE, Olale F, Tsai HJ, Yelon D. Functional modulation of cardiac form through regionally confined cell shape changes. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mably JD, Modhideen MA, Burns CG, Chen JN, Fishman MC. Heart of glass regulates the concentric growth of the heart in zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2138–2147. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baker K, Warren KS, Yellen G, Fishman MC. Defective 'pacemaker' current (Ih) in a zebrafish mutant with a slow heart reate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4554–4559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jacob E, Drexel M, Schwerte T, Pelster B. Influence of hypoxia and of hypoxemia on the development of cardiac activity in zebrafish larvae. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R911–R917. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00673.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vermot J, Forouhar AS, Liebling M, Wu D, Plummer D, Gharib M, Fraser SE. Reversing blood flows act through klf2a to ensure normal valvulogenesis in the developing heart. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nagai Y, Asaoka Y, Namae M, Saito K, Momose H, Mitani H, Furutani-Seiki M, Katada T, Nishina H. The LIM protein Ajuba is required for ciliogenesis and left-right axis determination in medaka. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:887–893. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Witzel HR, Jungblut B, Choe CP, Crump JG, Braun T, Dobreva G. The LIM protein Ajuba restricts the second heart field progenitor pool by regulating Isl1 activity. Dev Cell. 2012;23:58–57. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Essner JJ, Vogan KJ, Wagner MK, Tabin CJ, Yost HJ, Brueckner M. Conserved function for embryonic nodal cilia. Nature. 2002;418:37–38. doi: 10.1038/418037a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Essner JJ, Amack JD, Nyholm MK, Harris EB, Yost HJ. Kupffer's vesicle is a ciliated organ of asymmetry in the zebrafish embryo that initiates left-right development of the brain, heart and gut. Development. 2005;132:1247–1260. doi: 10.1242/dev.01663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kramer-Zucker AG, Olale F, Haycraft CJ, Yoder BK, Schier AF, Drummond IA. Cilia-driven fluid flow in the zebrafish pronephros, brain and Kupffer's vesicle is required for normal organogenesis. Development. 2005;132:1907–1921. doi: 10.1242/dev.01772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wessely O, Obara T. Fish and frogs: Models for vertebrate cilia signaling. Front Biosci. 2008;13:1866–1880. doi: 10.2741/2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Swanhart LM, Cosentino CC, Diep CQ, Davidson AJ, de Caestecker M, Hukriede NA. Zebrafish kidney development: basic science to translational research. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2011;93:141–156. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brueckner M. Impact of genetic diagnosis on clinical management of patients with congenital heart disease: Cilia point the way. Circulation. 2012;125:2178–2180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.103861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Svensson LG. Percutaneous aortic valves: Effective in inoperable patients, what price in high-ris patients? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140(6 Suppl):S10–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.07.037. discussion S86–S91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Poss KD, Wilson LG, Keating MT. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Science. 2002;298:2188–2190. doi: 10.1126/science.1077857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Myklebust R, Engedal H, Saetersdai TS, Ulstein M. Primary 9 + 0 cilia in the embryonic and the adult human heart. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1977;151:127–139. doi: 10.1007/BF00297476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Beis D, Bartman T, Jin SW, Scott IC, D'Amico LA, Ober EA, Verkade H, Frantsve J, Field HA, Wehman A, et al. Genetic and cellular analyses of zebrafish atrioventricular cushion and valve development. Development. 2005;132:4193–4204. doi: 10.1242/dev.01970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Smith KA, Langendijk AK, Courtney AD, Chen H, Paterson D, Hogan BM, Wicking C, Bakkers J. Transmembrane protein 2 (Tmem2) is required to regionally restrict atrioventricular canal boundary and endocardial cushion development. Development. 2011;138:4193–4198. doi: 10.1242/dev.065375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]