Abstract

This article sets out to investigate the psychiatric and psychosocial risk factors for high risk sexual behaviour in a war-affected population in Eastern Uganda. A cross-sectional survey was carried out in four sub-counties in two districts in Eastern Uganda where 1560 randomly selected respondents (15 years and above) were interviewed. The primary outcome was a derived variable “high risk sexual behaviour” defined as reporting at least one of eight sexual practices that have been associated with HIV transmission in Uganda and which were hypothesised could arise as a consequence of psychiatric disorder or psychosocial problems. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess factors associated with high risk sexual behaviour in this population. Males were more likely to have at least one “high risk sexual behaviour” than females (11.8% vs. 9.1% in the last year). Sex outside marriage was the most commonly reported high risk sexual behaviour. Among males, the factors independently associated with high risk sexual behaviour were: being married, belonging to non-Catholic/non-Protestant religions, poverty, being a victim of intimate partner violence and having a major depressive disorder (MDD). Among females, the factors that were independently associated with high risk sexual behaviour were: being in the reproductive age groups of 25–34 and 35–44 years, not seeing a close relative killed and having experienced war-related sexual torture. Holistic HIV/AIDS prevention programming in conflict and post-conflict settings should address the psychiatric and psychosocial well-being of these communities as a risk factor for HIV acquisition.

Keywords: high risk sexual behaviour, risk factors, psychiatric disorder, conflict/post-conflict settings, major depressive disorder

Background

The association between HIV/AIDS and psychiatric disorder is complex and includes that psychiatric disorder may increase one’s risk of acquiring HIV/AIDS (Collins, Holman, Freeman, & Patel, 2006). Literature, mainly from the west, has reported the following psychiatric and psychosocial factors to be associated with HIV risk and infection: alcohol use and abuse, major depressive disorder (MDD), sexual abuse and war conflict (Jewkes et al., 2006a, 2006b; Kalichman, Simbayi, Kaufman, Cain, & Jooste, 2007; Kinyanda et al., 2010; Koblina et al., 2006; Mbulaiteye et al., 2000; Miller, 1999; Mock et al., 2004; Plotzker, Metzger, & Holmes 2007; Townsend et al., 2010; Uganda AIDS Commission [UAC], 2006; Yang, Li, Stanton, Chen, & Liu, 2005). There is a paucity of data from Africa on the relationship between psychiatric and psychosocial factors in HIV risk and HIV infection.

Despite Uganda’s initial successes in controlling the HIV epidemic, there is concern that since 2000, the epidemic has “stagnated” and is even on the increase in some parts of the country, this has prompted calls for continued research into vulnerability factors for HIV infection (UAC, 2005, 2006).

Trends in the prevalence of probable MDD in Uganda to some extent have mirrored the picture of both violent conflict and HIV sero-prevalence trends in the country. While the prevalence of MDD in the non-war-affected southern and western parts of the country is about 20% (Bolton, Wilk, & Ndogoni, 2004; Kinyanda et al., 2009; Orley & Wing, 1979), that in war-affected northern and eastern Uganda is in excess of 40% (Kinyanda et al., 2009; Vinck, Pham, Stover, & Weinstein, 2007). We hypothesised that the trends of HIV sero-prevalence, conflict and the associated psychiatric disorder were linked together and that psychiatric and psychosocial problems were a risk factor for risky sexual behaviour in the African sociocultural context of Uganda.

Methodology

A cross-sectional survey was carried out in four subcounties in the two districts of Amuria and Katakwi in war-affected eastern Uganda. This study was nested within UAC (Civil Society Fund) funded project to address HIV-related psychiatric and psychosocial vulnerabilities in the war-affected community (the first such project to be funded by UAC).

Sampling procedure

A multistage sampling procedure was used where a representative sample of both vulnerable (vulnerable persons included groups such as widows, war orphans, single mothers; (Kinyanda et al., 2010; Musisi, Kinyanda, Leibling, & Mayengo, 2000) and non-vulnerable individuals was recruited into the study. This sample was drawn from the four sub-counties in the districts of Amuria and Katakwi where the NGO, Transcultural Psychosocial Organisation (TPO), was carrying out a psychosocial project. The sampling unit was the vulnerable person in the selected households. Only one vulnerable person was selected per household.

A sample size of 268 per sub-county was calculated using the formula:

| (1; Cochran; 1963) |

In Equation (1), n is the sample size, z is the t-statistic for 95% confidence interval, p the probability of the event, q = 1 − p, and d level of precision desired.

To realise this sample size, 15 villages per sub-county were randomly selected. In each village a comprehensive listing of vulnerable and non-vulnerable individuals by household was done. Eighteen vulnerable individuals and six non-vulnerable individuals (the comparison group) (one third of the vulnerable sample) were randomly selected from each village for interview. In total, a sample of 1440 was calculated which was adjusted to 1584 (+10% to take care of possible losses).

Data collection tools

The mental health modules used in the data collection tool was translated into Itesot (the local language spoken in the region) by forward and back translation by two teams of mental health professionals conversant with both English and the local language who at the end of the exercise had a consensus meeting to resolve any major differences in the two translations. When translating the mental health modules from English into Luganda the mental health team aimed to transmit into the local language the underlying mental health concept behind the constituent items of the module. Non-medical interviewers who had previously participated in demographic surveillance data collection exercises with the Uganda Bureau of Statistics were recruited as research assistants and trained into basic concepts of psychological distress and into use of the different study modules.

Measures

The data collection tool contained the following modules

Socio-demographics

(a) residence information; (b) sex; (c) age in completed years; (d) tribe; (e) religion; (f) marital status; (g) highest level of education; (h) current employment status and (i) status in the household (head of household, female spouse, offspring, other relative and household help).

Vulnerability assessment checklist

This consisted of a list of characteristics given in the definition of a vulnerable person (given earlier).

Poverty index

A poverty index was constructed from the 18 items from the definition of poverty of the Uganda Participatory Poverty Assessment Project (Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development, Uganda, 2000). For each item, a respondent was required to indicate whether: 0 = does not apply; 1 = mildly applies; 2 = moderately applies and 3 = significantly applies.

High risk sexual behaviours

This section assessed for eight high risk sexual behavioural practices reported in the Ugandan culture by the various HIV sero-behavioural surveys in which it was hypothesised that they could arise as a consequence of a psychiatric disorder or a psychosocial problem (Ministry of Health, Uganda, 2005; UAC, 2005, 2006; Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2006). The high risk sexual behavioural practices considered in this study included: sex outside marriage, sex in exchange for gifts, sex in exchange for money, sex in exchange for protection, sex with an older person, sex with someone known for less than a day, sex with uniformed personnel and sex with more than one partner.

Screen for psychological distress

The study assessed for: (a) Probable MDD: This was done using the 15-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25; Derogatis, Lipman, Rickels, Uhlenhuth, & Covi, 1974). A cut-off point of 31 (previously calibrated by Kinyanda et al., 2009) was taken as indicative of probable MDD. (b) Problem drinking of alcohol: This was assessed using the Cut, Anger, Guilt and Eye opener (CAGE) (Ewing, 1984) with probable problem drinking taken as having any two positive items of this scale. (c) Attempted suicide: This was assessed by means of two questions: “Have you ever attempted to take your life? (by ingesting poison, hanging, taking a drug overdose, drowning) in the previous 12 months; and in your lifetime?”

War torture experiences

These items were derived from the commonly reported forms of war trauma in Uganda (Kinyanda et al., 2010; Musisi et al., 2000).

Reproductive health complaints

(13 items) – including leaking urine (vaginal fistula), leaking faeces (rectal fistula), vaginal and perineal tears, sexual dysfunction and abnormal vaginal discharge (Mirembe, Biryabarema, Mutyaba, & Otim, 2001).

Surgical complaints

(9 items) – including chronic backache, broken limbs, disfigurement as a result of burns and swellings on limbs (Beyeza, Naddumba, & Kakande, 2001).

Intimate partner violence (IPV)

(11 items) – IPV was assessed by means of a modified Intimate Partner Violence Assessment Questionnaire adapted from the screening questionnaire used by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (2006). This instrument was asked to respondent who were married or had ever been married/or been in an intimate relationship, responses to the items being either yes or no.

Ethical issues

The study sought and obtained Ethical clearance from the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology and informed consent was sought from study participants. Study participants found to have significant scores on the various mental health assessment scales were referred for care in the TPO supported mental health clinics.

Analysis

The primary outcome in this study was a derived variable “high risk sexual behaviour” defined as reporting at least one of eight high risk sexual behavioural practices (described previously under the Section “Measures”). Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess factors associated with high risk sexual behaviour in this population. Factors associated with at least one high risk sexual behaviour in the past year were analysed using weighted logistic regression, for males and females separately. Factors associated with the outcome in the univariate analysis (p < 0.20) were included in a multivariable model. Those factors independently associated with the outcome in the multivariable model (p < 0.10) were retained in the final model.

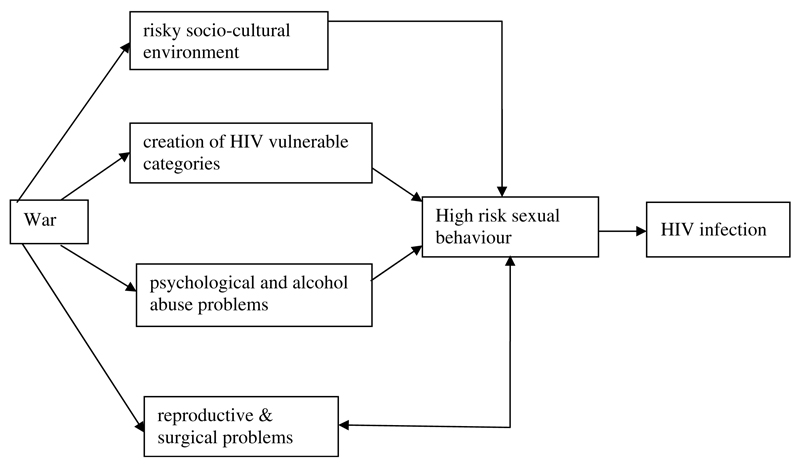

A conceptual framework was developed a priori specifying the anticipated relationships between the different variables (Figure 1) to guide the analysis.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework guiding the analysis of this data-set.

Results

Of 1584 selected respondents, 1560 (98.5%) eventually completed the interview; the reasons for failure to complete the interview 24 (1.5%) were that they were repeatedly not found at home by the research team. Those who did not complete the interview did not differ significantly from the completers in terms of age and gender.

General characteristics

Majority of the respondents (56%) were aged between 18 and 44 years, had low educational attainment (89.5% had no formal education or had < 8 years of formal schooling).

Prevalence of high risk sexual behaviours

Sex outside marriage was the most common high risk sexual behaviour reported by 11.9% of married participants in the past year, was more common in males than females (Table 1). For the other high risk sexual behaviours, there was little difference between the genders.

Table 1.

Prevalence of high risk sexual behaviour in the past one month and in the past one year to the study (N = 1560).

| Male (N = 673) |

Female (N = 887) |

Total (N = 1560) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High risk sexual behaviour | Last month | Last year | Last month | Last year | Last month | Last year |

| Sex outside marriagea | 37 (10.3) | 60 (16.6) | 21 (5.6) | 28 (7.4) | 58 (7.9) | 88 (11.9) |

| Sex in exchange for gifts | 13 (1.9) | 20 (3.0) | 18 (2.0) | 26 (2.9) | 30 (2.0) | 46 (2.9) |

| Sex in exchange for money | 4 (0.6) | 10 (1.5) | 10 (1.1) | 18 (2.0) | 13 (0.9) | 28 (1.8) |

| Sex in exchange for protection | 6 (0.9) | 11 (1.6) | 10 (1.1) | 16 (1.8) | 16 (1.0) | 27 (1.8) |

| Sex with older person | 9 (1.3) | 13 (1.9) | 7 (0.8) | 12 (1.3) | 16 (1.0) | 24 (1.5) |

| Sex with someone known less than a day | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.3) | 5 (0.5) | 4 (0.3) | 6 (0.4) |

| Sex with uniformed personnel | 7 (1.1) | 7 (1.1) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 9 (0.6) | 9 (0.6) |

| Sex with more than one partner | 14 (2.1) | 19 (2.8) | 11 (1.3) | 18 (2.0) | 25 (1.6) | 36 (2.3) |

Analysis only undertaken among those currently married.

The prevalence of the derived variable “high risk sexual behaviour in the past 12 months” was 9.1% (95%CI 7.7–10.7%), more common among males (11.8%, 95%CI 9.5–14.5%) than among females (7.2%, 95%CI 5.6–9.2%; Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of recent high risk sexual behaviour, by gender.

| Male (N = 658) |

Female (N = 902) |

Total (N = 1560) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least one high risk sexual behaviour | Last month | Last year | Last month | Last year | Last month | Last year |

| N | 55 | 77 | 44 | 65 | 99 | 142 |

| Prevalence | 8.4 | 11.8 | 4.9 | 7.2 | 6.4 | 9.1 |

| 95%CI | 6.5–10.7 | 9.5–14.5 | 3.6–6.6 | 5.6–9.2 | 5.2–7.7 | 7.7–10.7 |

Socio-demographic factors associated with high risk sexual behaviour in the past 12 months

In univariate analyses, among males, the factors significantly associated with high risk sexual behaviour in the last 12 months were older age (highest among those in the age group of 25–34 years), being married, non-Catholic/non-Protestant religions and increased poverty (Table 3). Among females, high risk sexual behaviour was associated with being in the reproductive age groups of 25–34 and 35–44 years.

Table 3.

Association of high risk sexual behaviour in the past 12 months with socio-demographic factors.

| Males |

Females |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number in study (N) N (%) | Number with high risk behaviour (n, %) | Univariate OR (95%CI) | Number in study (N) N (%) | Number with high risk behaviour (n, %) | Univariate OR (95%CI) | |

| Socio-demographic factors | ||||||

| Age (years) | P = 0.002 | P = 0.11 | ||||

| 15–24 | 234 (35.9) | 12 (5.2) | 1 | 211 (23.6) | 9 (4.0) | 1 |

| 25–34 | 117 (18.0) | 26 (22.2) | 5.16 (2.46–10.81) | 174 (19.5) | 17 (10.0) | 2.61 (1.12–6.10) |

| 35–44 | 117 (17.9) | 15 (12.4) | 2.57 (1.13–5.85) | 197 (22.0) | 21 (10.6) | 2.83 (1.16–6.86) |

| 45–54 | 67 (10.3) | 8 (12.6) | 2.61 (0.98–6.91) | 118 (13.2) | 8 (6.4) | 1.61 (0.59–4.37) |

| 55–64 | 42 (6.5) | 5 (11.3) | 2.29 (0.75–6.96) | 90 (10.0) | 3 (3.4) | 0.84 (0.22–3.23) |

| ≥ 65 | 75 (11.4) | 10 (13.9) | 2.92 (1.19–7.13) | 104 (11.6) | 7 (10.4) | 1.63 (0.52–5.12) |

| Marital status | P < 0.001 | P = 0.11 | ||||

| Never married | 242 (36.8) | 8 (3.3) | 1 | 208 (23.1) | 15 (7.2) | 1 |

| Married | 362 (55.0) | 67 (18.5) | 6.64 (3.08–14.32) | 383 (42.6) | 36 (9.3) | 1.32 (0.70–2.50) |

| Divorced/widowed | 54 (8.2) | 3 (4.8) | 1.46 (0.37–5.84) | 309 (34.3) | 14 (4.6) | 0.62 (0.28–1.40) |

| Education level | P = 0.67 | P = 0.20 | ||||

| No education | 254 (38.7) | 33 (15.3) | 1 | 514 (57.2) | 42 (8.2) | 1 |

| Primary only | 294 (44.8) | 30 (10.2) | 0.77 (0.45–1.32) | 336 (37.4) | 18 (5.3) | 0.63 (0.35–1.14) |

| Secondary 1–4 | 86 (13.1) | 12 (15.6) | 1.10 (0.54–2.24) | 44 (4.9) | 5 (11.2) | 1.41 (0.47–4.25) |

| Secondary 5 or more | 22 (3.4) | 2 (8.7) | 0.65 (0.15–2.92) | 5 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Religion | P = 0.11 | P = 0.44 | ||||

| Catholic | 417 (63.5) | 45 (11.0) | 1 | 593 (66.0) | 41 (6.9) | 1 |

| Protestant | 222 (33.8) | 28 (12.4) | 1.19 (0.71–1.97) | 277 (30.8) | 23 (8.4) | 1.25 (0.71–2.18) |

| Other | 18 (2.8) | 5 (28.3) | 3.30 (1.08–10.10) | 29 (3.2) | 0 (0) | – |

| Poverty indexa | P = 0.03 | P = 0.23 | ||||

| Low ( ≤ 23) | 202 (30.7) | 15 (7.4) | 1 | 273 (30.2) | 26 (9.6) | 1 |

| Medium (24–30) | 232 (35.2) | 37 (15.8) | 2.33 (1.23–4.41) | 314 (34.8) | 19 (6.1) | 0.61 (0.32–1.16) |

| High ( ≥ 30) | 224 (34.1) | 26 (11.4) | 1.61 (0.83–3.11) | 316 (35.0) | 20 (6.2) | 0.63 (0.33–1.20) |

Based on the total score calculated from an 18 item poverty question, with each item scored on a Likert scale where 0 (min) to 3 (max).

War-related psychosocial factors associated with high risk sexual behaviour in the past 12 months

Table 4 shows the war-related psychosocial factors associated with high risk sexual behaviour, among males were being a victim of intimate partner violence (OR = 3.24, 95%CI 1.88–5.59) and marginally, physical torture (OR = 1.55, 95%CI 0.96–2.53). Among females, factors associated with high risk behaviour were sexual torture (OR = 2.50, 95%CI 1.43–4.36) and physical torture (OR = 1.90, 95%CI 1.90–3.35). Females who reported seeing a close relative killed were less likely to report high risk sexual behaviour in the past 12 months (OR = 0.59, 95%CI 0.34–1.04).

Table 4.

Association of high risk sexual behaviour in the past 12 months with war-related psychosocial factors.

| Males |

Females |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number in study N (%) | Number with high risk behaviour (n, %) | Univariate OR (95%CI) | Number in study N (%) | Number with high risk behaviour (n, %) | Univariate OR (95%CI) | |

| Vulnerabilitya | P = 0.29 | P = 0.55 | ||||

| Not high risk | 154 (27.8) | 20 (13.2) | 1 | 169 (21.3) | 10 (6.0) | 1 |

| High risk | 401 (72.3) | 40 (10.0) | 0.73 (0.40–1.31) | 627 (78.7) | 46 (7.4) | 1.25 (0.60–2.62) |

| Intimate partner violence | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.24 | ||||

| No | 242 (36.8) | 24 (9.8) | 1 | 383 (42.4) | 21 (5.6) | 1 |

| Yes | 174 (26.5) | 46 (26.1) | 3.24 (1.88–5.59) | 311 (34.5) | 29 (9.2) | 1.71 (0.91–3.21) |

| Not applicable (unmarried) | 242 (36.7) | 8 (3.3) | 0.31 (0.14–0.72) | 208 (23.1) | 15 (7.2) | 1.31 (0.64–2.72) |

| Exposure to war torture | ||||||

| Close relative killedb | P = 0.16 | P = 0.07 | ||||

| No | 387 (58.8) | 40 (10.2) | 1 | 499 (55.3) | 43 (8.7) | 1 |

| Yes | 271 (41.2) | 38 (13.9) | 1.42 (0.88–2.30) | 403 (44.7) | 22 (5.4) | 0.59 (0.34–1.04) |

| Sexual torture | P = 0.06 | P = 0.001 | ||||

| No | 581 (88.2) | 63 (10.9) | 1 | 735 (81.4) | 43 (5.8) | 1 |

| Yes | 78 (11.8) | 14 (18.4) | 1.85 (0.99–3.47) | 168 (18.6) | 22 (13.3) | 2.50 (1.43–4.36) |

| Physical torture | P =0.08 | P = 0.03 | ||||

| No | 354 (53.8) | 34 (9.6) | 1 | 453 (50.2) | 23 (5.1) | 1 |

| Yes | 304 (46.2) | 43 (14.2) | 1.55 (0.96–2.53) | 449 (49.8) | 42 (9.3) | 1.90 (1.08–3.35) |

| Psychological torture | P = 0.23 | P = 0.95 | ||||

| None | 39 (6.0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 56 (6.2) | 4 (7.5) | 1 |

| One | 76 (11.5) | 8 (10.4) | 3.34 (0.69–16.03) | 117 (12.9) | 7 (5.8) | 0.76 (0.20–2.87) |

| Two | 370 (56.2) | 42 (11.3) | 2.92 (0.68–12.53) | 612 (67.9) | 45 (7.4) | 0.99 (0.34–2.92) |

| Three or more | 173 (26.3) | 28 (16.0) | 4.11 (0.93–18.06) | 117 (13.0) | 9 (7.4) | 0.99 (0.29–3.43) |

“Recently suffered heavy floods or famine” excluded as these were almost universal.

Includes parent, child, spouse or sibling (not other relative as this was too common).

Psychiatric and medical problems associated with high risk sexual behaviour in the past 12 months

Table 5 shows the univariate association’s high risk sexual behaviour and psychiatric and medical problems. Among males, these were alcohol use (both non-problem drinking OR = 2.07, 95%CI 1.11–3.86 and problem drinking OR = 2.21, 95%CI 1.26–3.88 compared with being a non-drinker), and marginally, having MDD (OR = 1.61, 95%CI 0.99–2.62). Among females, factors associated with high risk behaviour were having a surgical complaint (OR = 3.00, 95%CI 1.26–7.12) and marginally, alcohol use (both non-problem drinking OR = 1.84, 95%CI 0.94–3.60 and problem drinking OR = 1.90, 95%CI 0.97–3.70 compared with being a non-drinker).

Table 5.

Association of high risk sexual behaviour in the past 12 months with psychiatric and medical problems.

| Males |

Females |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number in study N (%) | Number with high risk behaviour (n, %) | Univariate OR (95%CI) | Number in study N (%) | Number with high risk behaviour (n,%) | Univariate OR (95%CI) | |

| Alcohol consumption | P = 0.01 | P = 0.07 | ||||

| Non-drinker | 388 (59.0) | 33 (8.4) | 1 | 642 (71.2) | 38 (5.9) | 1 |

| Not problem drinker | 118 (17.9) | 19 (16.0) | 2.07 (1.11–3.86) | 128 (14.2) | 13 (10.3) | 1.84 (0.94–3.60) |

| Problem drinker | 152 (23.1) | 26 (16.9) | 2.21 (1.26–3.88) | 133 (14.7) | 14 (10.6) | 1.90 (0.97–3.70) |

| Surgical complaintsa | P = 0.46 | P = 0.01 | ||||

| No | 603 (91.7) | 69 (11.5) | 1 | 856 (94.9) | 57 (6.6) | 1 |

| Yes | 55 (8.4) | 8 (14.9) | 1.35 (0.61–3.02) | 46 (5.2) | 8 (17.6) | 3.00 (1.26–7.12) |

| Reproductive health complaintsb | P = 0.45 | P = 0.25 | ||||

| No | – | – | – | 713 (79.1) | 48 (6.7) | 1 |

| Yes | – | – | – | 189 (20.9) | 17 (9.2) | 1.41 (0.79–2.53) |

| Major depressive disorderc | P = 0.06 | P = 0.57 | ||||

| No | 427 (64.8) | 42 (9.9) | 1 | 470 (52.1) | 31 (6.7) | 1 |

| Yes | 232 (35.2) | 34 (15.1) | 1.61 (0.99–2.62) | 432 (47.9) | 33 (7.7) | 1.17 (0.68–2.01) |

| Attempted suicide in past year | P = 0.26 | P = 0.48 | ||||

| No | 645 (97.8) | 74 (11.5) | 1 | 875 (97.0) | 62 (7.1) | 1 |

| Yes | 13.4 (2.0) | 3 (21.6) | 2.11 (0.57–7.82) | 27.4 (3.0) | 3 (10.8) | 1.58 (0.45–5.60) |

Includes 9 items such as: broken bones, wound, lost limb, burns, body parts having been forcibly cut-off.

Includes 13 items such as: abnormal vaginal discharge, leaking urine continuously (urinary fistula), infertility, unwanted pregnancy and genital sores.

Defined as >30 on the HSCL-15 depressive symptom scale.

Multivariable model for correlates of high risk sexual behaviour in the past 12 months

The multivariable models (Table 6) show that three domains of risk factors were independently associated with high risk sexual behaviour, namely; socio-demographic factors, war-related psychosocial factors and psychiatric and medical problems. Among males, the factors independently associated with high risk sexual behaviour were: being married, belong to non-Catholic/non-Protestant religions, poverty, being a victim of intimate partner violence and having MDD.

Table 6.

Multivariable model for high risk sexual behaviour in the past 12 months.

| Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|

| Factor | Adjusted OR (95%CI)a | Adjusted OR (95%CI)b |

| Socio-demographic factors | ||

| Age (years) | P = 0.21 | P = 0.05 |

| 15–24 | 1 | 1 |

| 25–34 | 2.26 (0.96–5.34) | 2.64 (1.06–6.63) |

| 35–44 | 1.03 (0.39–2.68) | 3.26 (1.32–8.08) |

| 45–54 | 0.95 (0.31–2.93) | 1.52 (0.54–4.25) |

| 55–64 | 1.39 (0.42–4.63) | 0.89 (0.21–3.69) |

| ≥ 65 | 1.76 (0.63–4.93) | 1.42 (0.40–5.01) |

| Marital status | P = 0.0003 | P = 0.27 |

| Never married | 1 | 1 |

| Married | 3.83(1.73–8.49) | 1.02 (0.48–2.18) |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 0.77 (0.18–3.34) | 0.53 (0.19–1.47) |

| Education level | P = 0.35 | P = 0.09 |

| No education | 1 | 1 |

| Primary only | 0.76 (0.42–1.36) | 0.65 (0.35–1.22) |

| Secondary 1–4 | 1.43 (0.68–3.00) | 2.27 (0.66–7.75) |

| Secondary 5 or more | 0.63 (0.12–3.24) | – |

| Religion | P = 0.02 | P = 0.69 |

| Catholic | 1 | 1 |

| Protestant | 1.41 (0.82–2.41) | 1.12 (0.64–1.98) |

| Other | 6.21 (1.57–24.3) | – |

| Poverty index | P = 0.02 | P = 0.13 |

| Low ( ≤ 23) | 1 | 1 |

| Medium (24–30) | 2.28 (1.09–4.76) | 0.56 (0.28–1.10) |

| High ( ≥ 30) | 1.10 (0.52–2.35) | 0.52 (0.26–1.06) |

| War-related psychosocial factors | ||

| Intimate partner violence | P <0.0001 | P =0.60 |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 3.34 (1.88–5.95) | 1.37 (0.71–2.64) |

| Close relative killed | P = 0.24 | 0.008 |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.38 (0.81–2.37) | 0.42 (0.23–0.80) |

| Sexual torture | P = 0.17 | P = 0.01 |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.62 (0.81–3.23) | 2.17 (1.21–3.92) |

| Physical torture | P = 0.36 | P = 0.08 |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.27 (0.76–2.15) | 1.75 (0.94–3.25) |

| Psychiatric and medical factors | ||

| Major depressive disorder | P = 0.05 | P = 0.91 |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.70 (1.01–2.86) | 1.03 (0.59–1.80) |

| Alcohol use | P = 0.16 | P = 0.17 |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes – not a problem drinker | 1.67 (0.83–3.34) | 1.68 (0.84–3.37) |

| Yes – problem drinker | 1.73 (0.92–3.23) | 1.76 (0.86–3.59) |

Adjusted for marital status, religion, poverty index, intimate partner violence, depressive disorder.

Adjusted for age group, education level, close relative killed, sexual torture, physical torture, alcohol use.

Among females, the factors that were independently associated with high risk sexual behaviour were: being in the reproductive age groups of 25–34 and 35–44 years, not seeing a close relative killed and having experienced war-related sexual torture.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies in the published literature that has examined the relationship between psychiatric disorder and psychosocial factors with high risk sexual behaviour in a war-affected setting in sub-Saharan Africa.

Prevalence of high risk sexual behaviour

The most prevalent high risk sexual behaviour reported in this study was sex outside marriage reported by 16.6% of married males and 7.4% of married females. These findings are in agreement with the current trends in the HIV epidemic in Uganda, where sexual transmission currently contributes 76% of new HIV infections in Uganda of which 43% are among persons in monogamous relationships and 46% among persons reporting multiple partnerships and their partners (Odit, 2008).

Psychiatric disorder and psychosocial factors associated with high risk sexual behaviour in the past 12 months

Alcohol use and abuse in this study was associated with a two fold increased risk to high risk sexual behaviour compared to non-alcohol use in both genders; this relationship, however, did not retain significance at multivariate analysis. These results are agreement with the literature which shows a positive association between alcohol use and abuse and risky sexual behaviour (Kalichman et al., 2007).

Explanations for the association between alcohol use and abuse and vulnerability to HIV include that: (1) alcohol and other drugs impair judgement and may lead to poor decisions regarding sexual behaviour; (2) adults with substance abuse disorder often cannot work and often live in circumstances and environments that are especially risky; (3) alcohol use and abuse can compromise the interpersonal and social skills needed to negotiate safer sexual relationships and may lead to less stable sexual partnerships, partnership concurrency, sexual bartering and risky sexual behaviour and (4) alcohol use and abuse may lead to inconsistent condom use, engagement in transactional sex and engagement in causal sexual partnerships (Miller, 1999; Townsend et al., 2010).

Major depressive disorder was at univariate analysis marginally associated with nearly a two fold increased risk for high risk sexual behaviour only among males in this study, this relationship was statistically significant at multivariate analysis. Many studies mainly from the west, including one from China have reported a positive association between MDD and HIV risk behaviour (Alegria et al., 1994; Koblina et al., 2006; Perdue et al., 2003; Plotzker et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2005). It has been suggested that depression may increase risky sexual behaviour through two mechanisms: (1) through participation in self destructive behaviour such as sharing needles with HIV infected drug injectors or sex trading directly for drugs or alcohol; (2) through the use of alcohol and drug used to modulate and relieve distressing affective symptoms (Miller, 1999).

Surgical health complaints were associated with a three fold increased risk for high risk sexual behaviour among females a relationship which was not observed among males. The immediate reasons for this association are not clear, but one possible explanation could be that surgical complaints (somatic complaints) may have been one form of expressing psychological distress in this African population, and it is this psychological distress that is associated with high risk sexual behaviour.

On psychosocial factors associated with high risk sexual behaviour, among females exposure to war-related sexual torture conferred a two fold increased risk of engaging in high risk sexual behaviour. Multiple studies have identified sexual abuse (both childhood abuse and rape) as a potent risk factor for HIV risk and HIV infection among females (Jewkes et al., 2006a, 2006b; Miller, 1999). Miller (1999) suggests that this relationship is mediated via the long term sequalae of sexual abuse such as: (1) initiation of and/or increasing reliance on alcohol and drug use as a method of coping with sexual abuse experiences; (2) problems with sexual adjustment (frequent sequalae include obsession with sexual activity, an inability to sustain intimate relationships, participation in destructive sexual relationships, and increased risk of divorce and separation); (3) psychopathology associated with sexual abuse (e.g., depression, PTSD, borderline personality disorder) which increase the likelihood of an individual participating in high risk behaviour and (4) social factors such as membership to deviant social networks (e.g., networks of drugs users), social isolation and lack of social support.

Other war conflict-related psychosocial factors found to be associated with high risk sexual behaviour in this study included war-related physical torture (in both gender) and exposure to intimate partner violence (physical and emotional; among males). According to UAC (2006) war leads to poverty, decay of cultural values, straining of family relationships and the emasculation of males all of which may predispose males to intimate partner violence.

In conclusion, both psychiatric and psychosocial risk factors were significantly associated with high risk sexual behaviour in both gender. There were, however, some differences on the specific factors associated with high risk sexual behaviour in the different gender. On psychosocial factors, it was both the direct consequences of war such as exposure to physical torture (both gender) and sexual torture (among females) and the indirect effects of war (exposure to intimate partner violence and poverty) among males that were associated with high risk sexual behaviour in this study. On psychiatric and medical problems, while alcohol use and abuse was significantly associated with high risk sexual behaviour in both gender, MDD was associated with high risk sexual behaviour only among males, while surgical health complaints were significantly associated with high risk sexual behaviour among females.

Limitations

As our study is based on a cross sectional survey design, the causal direction between the various investigated factors and high risk sexual behaviour cannot be demonstrated, it could only be inferred. Secondly, the use of the derived variable “high risk sexual behaviour” may have put together a diverse group of sexual behaviour practices which may be associated with psychiatric disorder and psychosocial factors through different mechanisms.

Recommendation

Firstly, HIV/AIDS prevention programmes in conflict and post-conflict settings should address the burden of psychiatric and psychosocial problems in these communities as they may be contributing to high risk sexual behaviour and hence the spread of HIV infection. Secondly, since to our knowledge this is the first study in the sub-Saharan African setting to investigate the associations between psychiatric and psychosocial factors in high risk sexual behaviour in a war-affected community, there is need for more studies in such settings.

References

- Alegría M, Vera M, Freeman DH, Robles R, Santos MC, Rivera CL. HIV infection, risk behaviors, and depressive symptoms among Puerto Rican sex workers. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(12):2000–2002. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.12.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Violence against women: screening tools. 2006 Retrieved from www.acog.org/departments/dept_notice.cfm?recno=17&bulletin=585.

- Beyeza T, Naddumba EK, Kakande B. Orthopaedic/surgical war related complications of women and men. In: Ojiambo-Ochieng R, Were-Oguttu J, Kinyanda E, editors. Medical intervention study of war-affected Gulu District, Uganda. Kampala: An Isis WICCE research report; 2001. pp. 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Wilk CM, Ndogoni L. Assessment of depression prevalence in rural Uganda using symptom and function criteria. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2004;39:442–447. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0763-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran WG. Sampling techniques. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PY, Holman AR, Freeman MC, Patel V. What is the relevance of mental health in HIV/AIDS care and treatment programs in developing countries? A systematic review. AIDS. 2006;20:1571–1582. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238402.70379.d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins symptom checklist (HSCL): A self report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science. 1974;19(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing AJ. Detecting alcoholism: The CAGE questionnaire. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1984;252:1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Koss MP, Levin JB, Nduna M, Jama N, Sikweyiya Y. Rape perpetration by young, rural South African men: Prevalence, patterns and risk factors. Social Science & Medicine. 2006a;63(11):2949–2961. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Khuzwayo N, Duvvury N. Factors associated with HIV sero-status in young rural South African women: Connections between intimate partner violence and HIV. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006b;35(6):1461–1468. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review of empirical findings. Prevention Science. 2007;8(2):141–151. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinyanda E, Musisi S, Biryabarema C, Ezati I, Oboke H, Ojiambo-Ochieng R, Walugembe J. War related sexual violence and it’s medical and psychological consequences as seen in Kitgum, Northern Uganda: A cross-sectional study. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 2010;10(28):10. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-10-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinyanda E, Woodburn P, Tugumisirize J, Kagugube J, Ndyanabangi S, Patel V. Poverty, life events and the risk for depression in Uganda. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;46(1):35–44. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0164-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblina BA, Husnikb MJ, Colfaxc G, Huangd Y, Madisone M, Mayerf K, Buchbinder S. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2006;20:731–739. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbulaiteye SM, Ruberantwari A, Nakiyingi JS, Carpenter LM, Kamali A, Whitworth JAG. Alcohol and HIV: A study among sexually active adults in rural southwest Uganda. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;29:911–915. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.5.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. A model to explain the relationship between sexual abuse and HIV risk among women. AIDS Care. 1999;11(1):3–20. doi: 10.1080/09540129948162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development, Uganda. The Uganda participatory poverty assessment report (2000) Kampala: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Uganda. HIV/AIDS serobeha-vioral survey 2004–2005. Kampala: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mirembe F, Biryabarema C, Mutyaba T, Otim T. The gynaecological effects of the armed conflict. In: Ojiambo-Ochieng R, Were-Oguttu J, Kinyanda E, editors. Medical interventional study of war-affected Gulu District, Uganda. Kampala: An Isis WICCE research report; 2001. pp. 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mock NB, Duale S, Brown LF, Mathys E, O’Maonaigh HC, Abul-Husn N, Elliott S. Conflict and HIV: A framework for risk assessment to prevent HIV in conflict-affected settings in Africa. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology. 2004;16(1) doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musisi S, Kinyanda E, Leibling H, Mayengo K. Posttraumatic torture disorders in Uganda-A three year retrospective study of patient records as seen at a specialized torture treatment center in Kampala, Uganda. Torture. 2000;10(3):81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Odit M. A review of the sources of incident HIV infection in Uganda, Modes of transmission Study: Uganda. Kampala: GoU/UNAIDS/UAC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Orley JH, Wing JK. Psychiatric disorders in two African villages. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1979;36:513–521. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780050023001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdue T, Hagan H, Thiede H, Valleroy L. Depression and HIV risk behavior among Seattle-area injection drug users and young men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15(1):81–92. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.81.23842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotzker RE, Metzger DS, Holmes WC. Childhood sexual and physical abuse histories, PTSD, depression, and HIV risk outcomes in women injection drug users: A potential mediating pathway. American Journal of Addiction. 2007;16(6):431–438. doi: 10.1080/10550490701643161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TA, Klein JD, Fisher S. Longitudinal effect of intimate partner abuse on high-risk behavior among adolescents. Archives of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157(9):75–81. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.9.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend L, Rosenthal SR, Parry CDH, Zembe Y, Mathews C, Flisher AJ. Associations between alcohol misuse and risks for HIV infection among men who have multiple female sexual partners in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2010:1–11. doi: 10.1080/0954012.2010.482128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UAC. The Uganda think tank on AIDS (UTTA). Is the ABC message still relevant in contemporary Uganda? Kampala: Author; 2005. (3rd report) [Google Scholar]

- UAC. Rapid assessment of trends and drivers of the HIV epidemic and effectiveness of prevention interventions in Uganda. Kampala: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (2006) Kampala: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vinck P, Pham PN, Stover E, Weinstein HM. Exposure to war crimes and implications for peace building in northern Uganda. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(5):543–554. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Li X, Stanton B, Chen X, Liu H. HIV-related risk factors associated with commercial sex among female migrants in China. Health Care Women International. 2005;26(2):134–148. doi: 10.1080/07399330590905585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]