Abstract

Given the widespread use of high quality cross-sectional imaging, cystic lesions of the pancreas are being diagnosed more frequently. Management of these lesions is challenging as it largely depends on radiologic and cyst fluid markers to discriminate between benign and pre-cancerous lesions, however the accuracy of these tests is limited, and unable to predict malignancy with certainty. While asymptomatic serous cystadenomas (SCA) can be managed conservatively, mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCN) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) are more difficult to manage given their variable potential for malignancy. A selective approach, based on the preoperative likelihood of high-grade dysplasia or invasive disease, is now the standard of care. Current research is focusing on the development of pre-operative markers for discriminating between histopathologic sub-types, and for identifying the degree of dysplasia in patients with precancerous mucinous lesions. Improvements in these diagnostic tools will hopefully limit resection to patients with high-risk lesions, and spare patients with low-risk or benign lesions the risks of pancreatectomy.

Keywords: pancreatic cysts, IPMN, serous cystadenoma, mucinous cystic neoplasms, pancreatectomy

Introduction

Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are being diagnosed more frequently given the widespread use of high quality imaging studies (CT and MRI). The reported prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts is about 2.6% on CT imaging, and has been reported to be as high as 13.5% on MR imaging. [1, 2]

The three most common subtypes of cystic neoplasms are serous cystadenoma (SCA), mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCN) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN). The latter represent the majority of neoplastic cystic lesions, and are of particular importance to surgeons as these lesions are considered to be precancerous. IPMN and MCN represent the only radiographically identifiable precursor lesions of pancreatic cancer.[3] The different classifications, subtypes, and diagnostic evaluation of cystic neoplasms are discussed in detail in the previous chapter.

Management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas is challenging as it involves decision making in the setting of imperfect diagnostic information. The decision between operative resection and radiographic surveillance must balance the risk of a significant operative procedure that has measurable associated mortality with the risk of malignant progression if radiographic surveillance is chosen.

Resection of all pancreatic cysts is no longer appropriate. The vast majority of lesions now identified are asymptomatic, small (<2cm), and benign. The risk of malignant progression in this group of patients is lower than the risk of operative resection. [3]

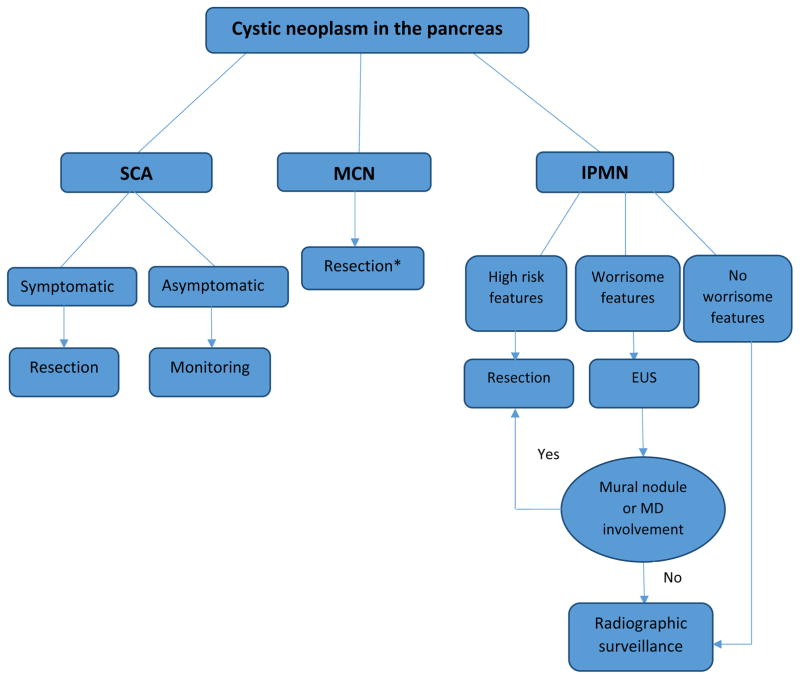

In this chapter, we will focus on the therapeutic approach to the three major subtypes of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas (IPMN, MCN and SCA), with the pre-stated understanding that determining the histopathology of a given cystic lesion, based on imaging and cyst-fluid analysis, is considered the cornerstone for managing these cysts. Treatment recommendations are usually based on the natural history, biologic behavior and risk of malignancy for each histologic subtype (Figure 1). Histopathology of small cysts can be hard to determine without resection and represent a clinical dilemma.

Figure 1. Overview of management of different types of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas.

MD: Main pancreatic duct, EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound, SCA: Serous cystadenoma, MCN: mucinous cystic neoplasm, IPMN: intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm.

* Monitoring in elderly with no worrisome features

1) Serous cystadenoma

Serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are considered benign slow-growing tumors (typically <5mm/year) with very rare malignant transformation. There have been approximately 30 reported cases of malignant transformation of SCA in the world literature, and these “malignant” SCA reports typically describe locally invasive lesions rather than metastatic disease.[4]

Asymptomatic SCAs should be managed conservatively with radiographic monitoring. [5] Monitoring with MRI or high resolution triphasic CT should typically be repeated within 3–6 months of initial diagnosis to both confirm the confidence of the diagnosis and to confirm radiographic stability. Once this has been performed, either annual or biennial imaging is appropriate. A recent observational study of 145 patients with SCA concluded that surveillance for SCA should not be more frequent than every 2 years based on the slow observed growth rate.[6] This study also showed that the rate of growth is dependent on the age of the cyst rather than the original size at presentation, as growth dramatically increased after the first 7 years of surveillance regardless of the original size. Other factors that increased the rate of growth were oligocystic/macrocystic pattern and a personal history of other tumors.

The exact growth rate of these lesions is unclear as a previous study by Tseng et al. reported that there was a difference in the growth rate of tumors < 4 cm (0.48 cm/yr) compared to those ≥ 4cm (1.98 cm/yr). These authors also reported that cysts >4 cm were more likely to be symptomatic, hence, they recommended resection for asymptomatic patients with serous cystadenomas > 4 cm.[7] These latter findings have not been observed in patients followed for SCA at our institution, and therefore we do not use the size of the lesion at presentation as a factor utilized in treatment decision making. [8]

We generally recommend resection in lesions that are clearly symptomatic, and for large lesions that are marginally resectable at presentation. Rapid growth, which is rarely observed, is another situation that may warrant resection.

Outcome and Long-Term Recommendations

Following resection, survival is only affected by operative mortality and post-operative complications, rather than the disease itself. In our series of 469 patients who underwent resection of pancreatic cysts (of all subtypes), the 30-day mortality rate was between 0.5% and 1%. [3] Postoperative surveillance following resection of serous cystadenoma is generally not indicated. There is no evidence of an increased risk of pancreatic cancer in this group of patients. [9]

2) Mucinous cystic neoplasms (cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma)

Similar to other cystic neoplasms, the clinical features and natural history of mucinous cysts dictates management as well as the surgical procedure of choice. These lesions are usually identified in women in their 4th or 5th decade as a solitary cyst in the body or tail of the pancreas. Characteristic radiographic features include a single cyst in the body or tail of the pancreas without significant papillary solid component. Egg shell calcifications may also be present. Cyst fluid analysis typically shows an elevated CEA level (mucin production) and low amylase (no communication with the pancreatic duct). [10, 11]

It is known that MCN have the potential to transform into malignancy and because these typically occur in the tail of the pancreas in young women, surgical resection is often recommended. Given that these lesions are typically unifocal, resection is considered curative as the pancreatic remnant has not been found to be at increased risk for the development of carcinoma. The risk of carcinoma in situ or invasive disease in published series of resected lesions has been reported around 17%.[12] Other features that reportedly increase the likelihood of invasive disease and, thus, warrant surgical resection are: symptomatic cysts, large size (> 4cm), elevated tumor marker and presence of solid component or mural nodule. [13, 14]

In elderly patients with multiple medical comorbidities that preclude surgical resection, monitoring of the lesion with serial imaging is an option, especially if there are no worrisome features (MCNs of <4 cm without mural nodules). This is generally done by MRI/MRCP, or triphasic multi-detector CT with 2 mm cuts through the pancreas. Once stability has been determined, annual imaging is appropriate. Notably, multiple studies have demonstrated that invasive MCN usually occur in older patients, without distinctive imaging characteristics. This is further evidence that we currently are unable to identify invasive MCN before it progresses from non-invasive precursor. Thus, resection should be considered in the majority of patients. [15]

Distal pancreatectomy with lymph node dissection with or without splenectomy is the most common procedure for MCN, as the majority of these cysts are located in the body or tail of the pancreas. Parenchyma-sparing resections (central pancreatectomy) may be performed in small MCNs without features of invasive disease. A recent metaanalysis showed that, compared to distal pancreatectomy, central pancreatectomy is associated with higher morbidity including higher pancreatic fistula but lower rate of post-op endocrine insufficiency.[16] This latter finding is a factor that should be considered as many patients with MCN are in their 30s or 40s at the time of resection. Pancreatic enucleation is also an option and is generally associated with less morbidity, shorter operative time and lower incidence of endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.[17] Enucleation for these lesions, however, is typically quite challenging as they are often >4cm in diameter and often thoroughly embedded within the parenchyma with an associated inflammatory infiltrate.

Laparoscopic resection with spleen preservation is feasible and safe for MCNs.[14] Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy has been thought to be associated with shorter hospital stay, less blood loss and decreased overall complications compared to the open approach. [18] EUS-guided ablation is still considered investigational and is not recommended for patients with MCN. [14]

Outcome and Long-Term Recommendations

Non-invasive MCN has no risk for distant recurrence after resection, and there is no increased risk of pancreatic cancer in the remaining pancreas with a 5-year survival close to 100%. Thus, these patients do not usually require long-term radiographic surveillance following resection.[15, 19] However, those who are found to have invasive MCN after resection are at risk for distant recurrence. Reported recurrence rates range from 37% to 83% at 5 years [4], while 5-year survival was reported as 57% in a large series of 163 resected MCN.[15] Per the 2012 international consensus guidelines, recommended follow up for invasive MCN is similar to resected pancreatic cancer, and usually consists of high quality CT scan (Pancreas-protocol scan) every 6 months for the first two years and then annually afterwards.[14]

3) Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas (IPMN)

IPMN are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms that arise in the ductal system of the pancreas and may involve the main pancreatic duct (MD-IPMN), branch ducts (BD-IPMN), or both (Mixed-IPMN). Since the recognition of this entity 2 decades ago, IPMN have been gaining increased attention as they are the most common radiographically identifiable precursor lesion of pancreatic cancer, and are presumed to evolve from low-grade dysplasia to high-grade dysplasia to carcinoma. This pathway of progression to pancreatic cancer is believed to represent between 20% – 30% of pancreatic cancer. Approximately 40%–70% of resected IPMN lesions will have either high-grade dysplasia or invasive carcinoma identified at the time of resection.[20, 21]

The two main histopathological subtypes of invasive IPMN that have been described are colloid carcinoma which typically arises in the setting of intestinal-type IPMN, and tubular carcinoma which generally arises in the setting of pancreatobiliary-type IPMN. There are currently no means of differentiating between these two sub-types preoperatively, however recent studies have suggested that GNAS mutations are strongly associated with colloid carcinoma and KRAS mutations associated with tubular carcinoma.[22] Preoperative distinction between these sub-types may be important as the outcomes following resection differ significantly with reported 5-year survival following resection of colloid carcinoma approximating 75%, while resected tubular invasive IPMN has a reported 5-year survival similar to that of conventional pancreatic cancer (15%–25%). [23, 24]

Generally, management of IPMN depends on the result of the initial CT or MRI/MRCP which will determine whether the patient needs further evaluation with EUS, surveillance or should undergo surgical resection. Per the 2012 Fukuoka consensus guidelines, high-risk features include an enhancing solid component or main pancreatic duct (MPD) size ≥10 mm. Cysts with either of these two features should be resected. Worrisome features include: pancreatitis (clinically), cyst ≥ 3 cm, thickened enhanced cyst walls, non-enhanced mural nodules, MPD size of 5–9 mm, abrupt change in the MPD caliber with distal pancreatic atrophy, and lymphadenopathy. Presence of any of these worrisome features warrants further work-up with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) to evaluate for mural nodules or MD involvement. If none of the previous features are present then no further work-up is indicated but radiographic surveillance is still warranted.[14]

A. Branch duct-IPMN (BD-IPMN)

BD-IPMN is defined as a pancreatic cyst of >5mm in diameter with communication with the MPD without associated MPD dilation. BD-IPMN is more common in the elderly and less likely to harbor high-grade dysplasia or invasive disease when compared to MD-IPMN. The annual risk of malignancy has been estimated to be between 2–3%.[25, 26]

For small <3 cm branch duct IPMN with no high-risk or worrisome features, radiographic monitoring is generally recommended, with resection reserved for symptomatic patients or those who develop worrisome features. The typical follow-up schedule at our institution for those undergoing non-operative management includes a short interval scan (3–6 months) to determine stability, and then either annual imaging or imaging every six months. Every six month imaging is generally reserved for patients in which there is some degree of concern such as a larger BD-IPMN or in the setting of minimal MDP dilation (<1cm).

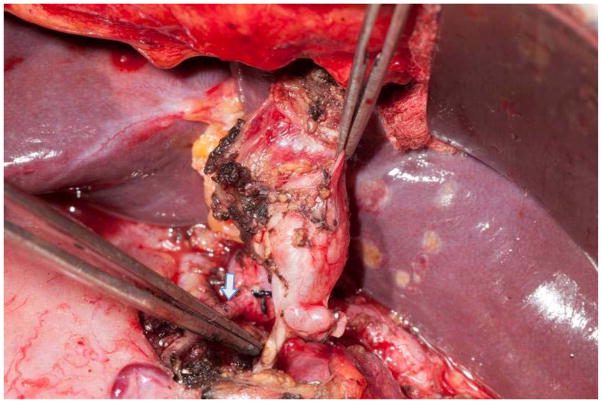

Indications for resection include the presence of symptoms or any of the high-risk stigmata or worrisome features described above. The procedure of choice is segmental pancreatectomy or enucleation depending on the location of the lesion (Figure 2). A standard resection with lymphadenectomy should be performed for segmental resections. Limited or focal non-anatomic resection is an option as long as there are no pre-operative or intraoperative concerns for malignancy.

Figure 2. Enucleation of a cystic tumor in the head of the pancreas.

Note the preservation of the gastroduodenal artery (arrow).

EUS-guided ablation of pancreatic cysts by ethanol or ethanol followed by paclitaxel is an investigational method that has been used in uni or oligo-locular cysts <2cm, cysts with no radiographic communication with the MPD, and in patients who refuse to undergo resection or are poor candidates for operation. [27–31] A recent meta-analysis of 7 studies that performed EUS-guided ethanol ablation of pancreatic cysts showed a pooled complete cyst resolution of 56 % and partial cyst resolution of 24 %, related complications included abdominal pain in 6.5 % of patients and pancreatitis in 3.9 %. [32] Concerns related to this approach are numerous, and include the inability to perform surveillance on collapsed cysts, the high risk of cyst recurrence, and the unknown effects of alcohol on incompletely ablated IPMN epithelium. [33]

For multifocal BD-IPMN, the number of lesions has not been demonstrated to correlate with the risk of invasive disease. Interestingly, one report showed that symptomatic unifocal BD-IPMN had a higher risk of malignancy compared to multifocal BD-IPMN (18% versus 7%).[34] Treatment includes segmental pancreatectomy for high risk lesions, with an attempt at avoiding total pancreatectomy whenever the lesions are confined to one pancreatic region.[14] The decision to proceed with total pancreatectomy is an extremely important one, with careful patient selection being essential. The long-term morbidity of total pancreatectomy is measurable and this procedure should only be considered for BD-IPMN when there is diffuse whole-gland involvement of high-risk lesions. [14, 35]

B. Main duct IPMN (MD-IPMN)

The 2012 Fukuoka consensus guidelines lowered the threshold for pancreatic dilation to 5mm from 10 mm as this would increase the sensitivity for radiologic diagnosis of MD-IPMN without compromising specificity. The recommendation for operative resection in MD-IPMN is less controversial than other cystic lesions as resection is typically indicated in all radiologically or endoscopically confirmed MD-IPMN given the high incidence of invasive and malignant disease. The greater challenge in MD-IPMN is not should an operation be done, but rather what operation should be done, as our ability to define the site of high-grade dysplasia or invasive disease in MD-IPMN is limited.[36]

Our typical approach to MD-IPMN is to assess for the presence of an invasive lesion, and to evaluate the pancreas for the predominant radiographic or endosonographic site of disease. When an invasive lesion is identified, partial pancreatectomy is performed to resect the site of invasive disease. In the absence of an invasive lesion, and in the setting of a clear radiographic predominance of disease in one portion of the gland, a partial pancreatectomy is typically performed to remove the area of radiographic predominance. Intraoperative frozen section is typically performed to rule out high grade-dysplasia at the resection margin. If high-grade dysplasia is present then further resection should be performed. Frozen section requires intact epithelium at the margin to be able to evaluate for the degree of dysplasia. The accuracy of frozen section however is limited with positive predictive value for frozen section of about 50% and a negative predictive value of up to 74%. [37]

In a study by our group at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), local recurrence in the remnant gland occurred in 8% of patients after a median of 36 months of follow up. Thus, all patients who have been resected for IPMN should be considered for long-term radiographic surveillance. High-grade dysplasia, and a margin positive for IPMN have been identified as risk factors for this recurrence, and should be considered when the interval of follow-up is being determined.[37]

In cases of diffuse ductal dilation without focal lesions on imaging, further work-up with ERCP\EUS should be performed to confirm the diagnosis, and to exclude an occult invasive lesion. [14, 38] In the absence of invasive disease, and in the absence of a site of predominant disease, total pancreatectomy should be considered. This operation should be reserved for selected patients with obvious diffuse disease or to those in whom the intraoperative finding of high grade dysplasia on frozen section dictates completion pancreatectomy. This selective approach is important given the significant morbidity of total pancreatectomy with the inevitable endocrine and exocrine insufficiency. This morbidity was demonstrated in a series of 47 patients from the Mayo Clinic who underwent total pancreatecetomy for non-invasive IPMN. Within this group the reported 30-day major morbidity and mortality rate was 19% and 2%, respectively. There were significant reported metabolic derangements, exocrine insufficiency, weight loss, diabetes and a high readmission rate. [39]

Outcome and Long-Term Follow up

Non-invasive IPMN should be at no risk for distant recurrence. Recurrence and survival following resection of invasive lesions is dependent on histologic subtype. In a recent multi-institutional study of 70 small IPMN-associated invasive carcinomas (≤2cm), the overall recurrence rate was 24% and the median time to recurrence was 16 months (range 4–132 months). Median and 5-year survival rates were 99 months and 59% respectively. Recurrence of invasive disease was local in 35%, distant in 47%, and both in 18% of patients. Lymphatic spread and T3 stage were predictive of recurrence, whereas tubular carcinoma subtype was the strongest predictor of poor overall survival.[40]

For resected non-invasive MD-IPMN, variable recurrence rates have been reported in the literature (5–20%) [37, 40–42], but close radiographic follow-up is recommended as these patients are presumed to have a higher risk of developing a new IPMN. This was demonstrated in a recent study from Johns Hopkins which found that these patients have a 25% chance of developing a new IPMN in the 5 years following surgery for non-invasive IPMN, and the risk of developing pancreatic cancer was 7% and 38% at 5 and 10 years, respectively.[41]

Another study of 78 patients who had undergone resection of non-invasive IPMN at MSK, found that 8% had recurrence in the pancreatic remnant at 36 months of median follow up and the 5 year recurrence rate was 13%. Local recurrence increased with positive margins, however, the majority of patients with positive margins have not developed local recurrence. Furthermore, recurrence in the pancreatic remnant was the same for both MD-IPMN and BD-IPMN, at 8%. [37]

4. Less common cystic neoplasms of the pancreas

A. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN)

SPNs are uncommon cystic lesions of the pancreas and represent <4% of resected pancreatic cystic lesions. SPNs are being more commonly reported in the literature, they can occur throughout the pancreas but more commonly occur in the body or tail. On imaging, SPNs appear as large, well-demarcated, solitary, mixed solid and cystic heterogeneous masses. [43]

Given the malignant potential of these lesions, surgical resection is typically recommended. The goal of resection is to obtain negative margins, and the procedure of choice depends on the location of the lesion (pancreaticoduodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy or enucleation).

Despite locally aggressive features, and even in the presence of metastatic disease, SPNs have a favorable prognosis following resection with 5-year survival rates of >95%. The recurrence rate is reported to be <5% and the mean time to tumor recurrence has been reported to be 4 years. There are currently no recommendations regarding surveillance but patients should be typically followed for at least 5 years. Male patients, those with atypical histopathology, large tumors >5cm, and patients with incomplete resection may have increased risk of recurrence and warrant closer follow up. [43, 44]

B. Cystic endocrine neoplasms

These lesions are considered malignant and behave similar to non-cystic endocrine tumors whose treatment and outcome is beyond the scope of this chapter. Endocrine tumors are typically indolent tumors, but have metastatic potential. Resection is recommended for all surgically fit patients, especially for patients with lesions >2 cm in size. Despite the potential for metastasis, overall prognosis is excellent with reported post-resection 1-year and 5-year survival of 97% and 87%, respectively.[45]

Summary

Management of cystic neoplasms will continue to evolve as our ability to diagnose and accurately identify histopathologic sub-type and the degree of dysplasia improves. SCAs are usually benign and only resected if symptomatic, while MCN and IPMN are considered premalignant and selective resection is indicated. Management of BD-IPMN depends on the presence of high risk or worrisome features. Currently, segmental pancreatectomy is the procedure of choice for mucinous lesions that have a malignancy risk that is greater than the risk of resection. MD-IPMN is typically treated with resection because of the higher risk of high-grade dysplasia or invasive disease.

In the absence of invasive disease, prognosis is excellent for resected lesions, while the presence of invasive disease with tubular histology in IPMN signifies a poor prognosis. Lifelong follow up is indicated regardless of the presence of invasion. Future research efforts should be focused on improving our ability to accurately diagnose the different histopathologic subtypes of pancreatic cysts, and to identify high-risk disease in patients with mucinous lesions, as this will result in better risk stratification and appropriate management.

Key points.

The incidence of pancreatic cysts has been increasing due to the widespread use of CT imaging.

Resection should be considered whenever the risk of malignancy is higher than the risk of the operation.

Serous cystadenomas are considered benign and should be followed radiographically, unless symptomatic.

Mucinous cystic neoplasms are typically resected as they are most frequently seen in young women and typically occur in the pancreatic body or tail.

Management of branch duct IPMN is selective with resection indicated for symptomatic lesions and those with high risk or worrisome features.

Main duct IPMN should generally be resected as there is presumed risk high-grade dysplasia or invasive disease.

The current challenges are to improve the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic testing for both histopathologic sub-type as well as degree of dysplasia.

Footnotes

Disclosure: This study was supported in part by NIH/NCI P30 CA008748 Cancer Center Support Grant.

References

* Meta-analysis

** Systamtic review

- 1.Laffan TA, Horton KM, Klein AP, et al. Prevalence of unsuspected pancreatic cysts on MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:802–807. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee KS, Sekhar A, Rofsky NM, Pedrosa I. Prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts in the adult population on MR imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2079–2084. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaujoux S, Brennan MF, Gonen M, et al. Cystic lesions of the pancreas: changes in the presentation and management of 1,424 patients at a single institution over a 15-year time period. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.016. discussion 600–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson SM, Scott J, Oppong KW, White SA. What to do for the incidental pancreatic cystic lesion? Surg Oncol. 2014;23:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galanis C, Zamani A, Cameron JL, et al. Resected serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: a review of 158 patients with recommendations for treatment. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:820–826. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malleo G, Bassi C, Rossini R, et al. Growth pattern of serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: observational study with long-term magnetic resonance surveillance and recommendations for treatment. Gut. 2012;61:746–751. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tseng JF, Warshaw AL, Sahani DV, et al. Serous Cystadenoma of the Pancreas. Transactions of the ..Meeting of the American Surgical Association. 2005;123:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen PJ, D’Angelica M, Gonen M, et al. A selective approach to the resection of cystic lesions of the pancreas: results from 539 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2006;244:572–582. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000237652.84466.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz MH, Mortenson MM, Wang H, et al. Diagnosis and management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: an evidence-based approach. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:106–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10**.Yoon WJ, Brugge WR. Pancreatic cystic neoplasms: diagnosis and management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2012;41:103–118. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cizginer S, Turner BG, Bilge AR, et al. Cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen is an accurate diagnostic marker of pancreatic mucinous cysts. Pancreas. 2011;40:1024–1028. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31821bd62f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crippa S, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Salvia R, et al. Mucin-producing neoplasms of the pancreas: an analysis of distinguishing clinical and epidemiologic characteristics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy RP, Smyrk TC, Zapiach M, et al. Pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasm defined by ovarian stroma: demographics, clinical features, and prevalence of cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00450-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14**.Tanaka M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crippa S, Salvia R, Warshaw AL, et al. Mucinous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas is not an aggressive entity: lessons from 163 resected patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:571–579. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31811f4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16*.Iacono C, Verlato G, Ruzzenente A, et al. Systematic review of central pancreatectomy and meta-analysis of central versus distal pancreatectomy. Br J Surg. 2013;100:873–885. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cauley CE, Pitt HA, Ziegler KM, et al. Pancreatic enucleation: improved outcomes compared to resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1347–1353. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1893-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kooby DA, Gillespie T, Bentrem D, et al. Left-sided pancreatectomy: a multicenter comparison of laparoscopic and open approaches. Ann Surg. 2008;248:438–446. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318185a990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamao K, Yanagisawa A, Takahashi K, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of mucinous cystic neoplasm with ovarian-type stroma: a multi-institutional study of the Japan pancreas society. Pancreas. 2011;40:67–71. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181f749d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchegiani G, Mino-Kenudson M, Sahora K, et al. IPMN involving the main pancreatic duct: biology, epidemiology, and long-term outcomes following resection. Ann Surg. 2015;261:976–983. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an increasingly recognized clinicopathologic entity. Ann Surg. 2001;234:313–321. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200109000-00005. discussion 321–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan MC, Basturk O, Brannon AR, et al. GNAS and KRAS Mutations Define Separate Progression Pathways in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm-Associated Carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:845–854. e841. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furukawa T, Kloppel G, Volkan Adsay N, et al. Classification of types of intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: a consensus study. Virchows Arch. 2005;447:794–799. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-0039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adsay NV, Merati K, Basturk O, et al. Pathologically and biologically distinct types of epithelium in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: delineation of an “intestinal” pathway of carcinogenesis in the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:839–848. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200407000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang MJ, Jang JY, Kim SJ, et al. Cyst growth rate predicts malignancy in patients with branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy P, Jouannaud V, O’Toole D, et al. Natural history of intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas: actuarial risk of malignancy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oh HC, Seo DW, Kim SC, et al. Septated cystic tumors of the pancreas: is it possible to treat them by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided intervention? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:242–247. doi: 10.1080/00365520802495537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh HC, Seo DW, Lee TY, et al. New treatment for cystic tumors of the pancreas: EUS-guided ethanol lavage with paclitaxel injection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:636–642. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oh HC, Seo DW, Song TJ, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided ethanol lavage with paclitaxel injection treats patients with pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:172–179. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gan SI, Thompson CC, Lauwers GY, et al. Ethanol lavage of pancreatic cystic lesions: initial pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:746–752. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeWitt J, McGreevy K, Schmidt CM, Brugge WR. EUS-guided ethanol versus saline solution lavage for pancreatic cysts: a randomized, double-blind study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:710–723. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.03.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32*.Kandula M, Moole H, Cashman M, et al. Success of endoscopic ultrasound-guided ethanol ablation of pancreatic cysts: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2015;34:193–199. doi: 10.1007/s12664-015-0575-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka M. Controversies in the management of pancreatic IPMN. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:56–60. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt CM, White PB, Waters JA, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: predictors of malignant and invasive pathology. Ann Surg. 2007;246:644–651. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318155a9e5. discussion 651–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi C, Klein AP, Goggins M, et al. Increased Prevalence of Precursor Lesions in Familial Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7737–7743. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maker AV, Katabi N, Qin LX, et al. Cyst fluid interleukin-1beta (IL1beta) levels predict the risk of carcinoma in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1502–1508. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White R, D’Angelica M, Katabi N, et al. Fate of the remnant pancreas after resection of noninvasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:987–993. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.040. discussion 993–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38**.Jana T, Shroff J, Bhutani MS. Pancreatic cystic neoplasms: Review of current knowledge, diagnostic challenges, and management options. J Carcinog. 2015;14:3. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.153285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stauffer JA, Nguyen JH, Heckman MG, et al. Patient outcomes after total pancreatectomy: a single centre contemporary experience. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:483–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winter JM, Jiang W, Basturk O, et al. Recurrence and Survival After Resection of Small Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm-associated Carcinomas (</=20-mm Invasive Component): A Multi-institutional Analysis. Ann Surg. 2015 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He J, Cameron JL, Ahuja N, et al. Is it necessary to follow patients after resection of a benign pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm? J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.12.026. discussion 665–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchegiani G, Mino-Kenudson M, Ferrone CR, et al. Patterns of Recurrence After Resection of IPMN: Who, When, and How? Ann Surg. 2015 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43**.Law JK, Ahmed A, Singh VK, et al. A systematic review of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms: are these rare lesions? Pancreas. 2014;43:331–337. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reddy S, Cameron JL, Scudiere J, et al. Surgical management of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas (Franz or Hamoudi tumors): a large single-institutional series. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:950–957. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.01.044. discussion 957–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaujoux S, Tang L, Klimstra D, et al. The outcome of resected cystic pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: a case-matched analysis. Surgery. 2012;151:518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]