Abstract

Despite medical and surgical advances leading to increased ability to restore or preserve gastrointestinal continuity, creation of stomas remains a common surgical procedure. Every ostomy results in a risk for subsequent parastomal herniation, which in turn may reduce quality of life and increase health care expenditures. Recent evidence-supported practices such as utilization of prophylactic reinforcement, attention to stoma placement, and laparoscopic-based stoma repairs with mesh provide opportunities to both prevent and successfully treat parastomal hernias.

Keywords: hernia, colostomy, ileostomy, parastomal, mesh

Despite exciting advances in surgical instrumentation and techniques, anesthetic management, postoperative care, and imaging modalities, a need still remains to create intestinal stomas under certain circumstances. In fact, the rate of stoma creation in the United States continues to increase in absolute terms, with an estimated 100,000 to 120,000 new colostomies or ileostomies per annum.1 By definition, an abdominal wall hernia is created during every stoma surgery. The reported incidence of parastomal herniation ranges from 28.3% for end ileostomy to 48% for permanent colostomy.2 While most parastomal hernias occur within the first 2 years postoperatively, the risk of herniation increases with time, and some surgeons believe parastomal hernias are inevitable. Parastomal hernia adversely impact quality of life with either small or large intestinal ostomies.3 4 Additionally, while exact measures of health care costs related to stomal hernias are unavailable, patients with parastomal hernias will have higher average ostomy-specific expenditures than those without.5 The goal of this article is to review the recent developments in both preventing and repairing symptomatic parastomal hernias, with an emphasis on novel approaches and evidence-supported practices.

Prevention of Parastomal Herniation

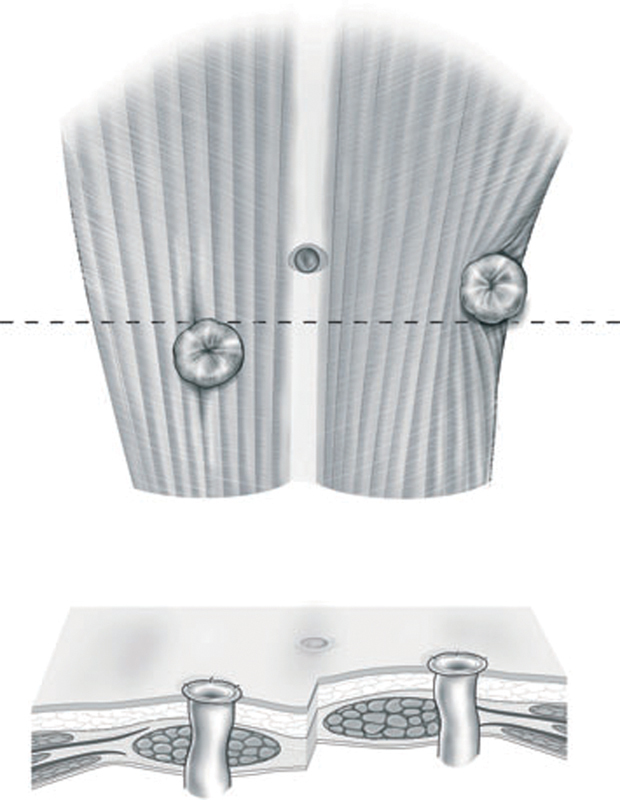

Placement through the Rectus Sheath

The current surgical teaching is to bring the stoma through the rectus sheath to reduce parastomal hernia formation. This dogma is based on a single study reporting a lower hernia rate when compared with a lateral pararectus approach (3 vs. 22%).5 6 However, some experts argue that hernia creation is actually higher when the paramedian structures are disturbed. The so-called lateral rectus abdominis positioned stoma (LRAPS) avoids disruption of the anterior abdominal wall by placing the stoma aperture lateral to the rectus musculature and re-approximating any disruption of the anterior or posterior rectus fascias (Fig. 1). Pilot study data in 72 patients found parastomal hernias in 10% at 2 years of clinical follow-up, which is markedly lower than most series employing transrectus ostomies.7 8 However, a Cochrane review of available data from nine studies comprising 761 patients found no difference in parastomal hernia rates between the lateral pararectus and transrectus approaches (relative risk: 1.29, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.79–2.1), albeit with very low quality of evidence due to small study sizes, varying techniques, and heterogeneity.9 Whether one technique to stoma creation is superior remains undetermined at this time.

Fig. 1.

Diagram showing the relative position of a standard ostomy compared with that using the lateral rectus abdominis positioned stoma (LRAPS) technique. (Reprinted with permission from Stephenson et al.8)

Extraperitoneal Colostomy

Extraperitoneal routing of the end stoma initially was described almost 70 years ago.10 11 This approach preserves the peritoneum over the internal aspect of stoma aperture, in effect producing the same anatomic–physiologic conditions as in the modified Sugarbaker parastomal hernia repair as described below. Despite promising reports in the literature,12 the extraperitoneal colostomy is not universally performed even when the planned ostomy is permanent (e.g., during abdominoperineal resection [APR]). Hamada et al recently reported on a technique to create an extraperitoneal colostomy during straight laparoscopic APR.13 In their retrospective cohort study, extraperitoneal colostomies developed parastomal herniation in only 4.5% of patients, compared with 33% using a transperitoneal approach (p = 0.03). Similarly, in a recent meta-analysis containing over 1,000 patients undergoing open surgery, extraperitoneal colostomy produced a significantly lower hernia rate (odds ratio: 0.41, 95% CI: 0.23–0.73).14 Additionally, no increased risk of stomal prolapse or bowel obstruction was observed using this technique. Given an equivalent complication profile and a potential for reduced parastomal herniation, strong consideration should be given to extraperitoneal colostomy creation when fashioning a permanent stoma.

Mesh Reinforcement

Even with optimal surgical technique, most stoma apertures invariably dilate with time. This dilatation seems particularly pronounced in older patients, diabetics, patients with malignancy, and those with increased intra-abdominal pressure due to central obesity, benign prostatic hypertrophy, or chronic coughing.2 12 15 16 The increased aperture size permits subsequent parastomal herniation. Thus, methods to reinforce the perimeter of the trephine at the time of stoma creation hold particular appeal.

Biologic Mesh

Historically, many surgeons have been hesitant to place permanent mesh in a potentially contaminated field. Even though it is considerably more expensive than synthetic mesh, biologically derived mesh is attractive because it may be less prone to chronic bacterial colonization. Likewise, the risk of colonic fistulization is probably diminished due to reduced erosion of the mesh into the bowel. Examples of widely available bioprosthetic materials include porcine-derived acellular dermis products such as cross-linked Permacol (Covidien, Norwalk, CT) and non–cross-linked Strattice (LifeCell, Bridgewater, NJ). Initial reports using these tissue scaffolds showed a significant reduction in parastomal hernia formation, albeit with small patient numbers and limited follow-up.17 18 However, these preliminary results were refuted by the PRISM (Parastomal Reinforcement with Strattice) study, a multicenter, prospective trial that randomized patients undergoing end-stoma creation to standard surgery compared with circumferential aperture reinforcement with Strattice in a retrorectus sublay manner.19 The tissue matrix was laid anterior to the posterior rectus fascia and precut with a 2-cm cruciate incision. At 24 months' follow-up, parastomal hernia rates were statistically identical in the two treatment arms: 10.2% in the reinforcement arm versus 13% in the control arm (relative risk: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.42–1.72). A lower than expected rate of parastomal hernia was observed in both study arms. The authors concluded that even though reinforcement with bioprosthetic was safe, its routine prophylactic use could not be recommended.19

Permanent Mesh

In contrast to biologic scaffolds, reinforcement of the fascial aperture using permanent mesh has been shown to significantly reduce subsequent parastomal herniation.20 21 22 23 24 Randomized, controlled trials have confirmed both the safety and the efficacy of this technique.15 25 26 27 28 These and other studies were analyzed in a recent systemic review.29 Shabbir et al found the overall incidence of parastomal hernia was significantly lower in the mesh-reinforcement group compared with controls (12.5 vs. 53%, p < 0.0001). Specific of several studies are discussed below.

Studies to date show considerable heterogeneity in surgical technique and materials utilized. Placement of the mesh is described in the onlay (superficial to the anterior rectus fascia),27 sublay/retromuscular (deep to the rectus musculature but superficial to the posterior fascia and/or peritoneum),25 26 28 30 or intraperitoneal positions.15 21 22 31 At least 5 cm of overlap between the mesh and surrounding abdominal wall should be achieved, so the piece of mesh must be 10- to 12-cm diameter in size. The mesh material is also highly variable across the literature. Most authors describe using some form of polypropylene, either in isolation as the macroporous lightweight variety27 30 or in a composite that incorporates biodegradable or anti-adhesion molecules.15 21 22 25 26 28 30 31 Mesh placement has been described using both open and laparoscopic surgical approaches. The safety of implanting synthetic mesh during a clean-contaminated bowel resection is well-established by multiple studies.15 20 21 22 25 26 27 28 31 In fact, no greater morbidity specific to mesh placement has been reported. Obviously, prudent judgment is necessary when dealing with the contaminated surgical fields occasionally encountered when ileostomy or colostomy creation is indicated. Mesh placement generally adds less than 30 minutes to the operative time.30

Overall, parastomal hernia rates are consistently lower in most studies examining synthetic mesh placement. At a median of 29 months' follow-up, Serra-Aracil et al found a hernia rate of 14.8% (vs. 40.7% for controls) in patients treated with Ultrapro mesh (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) placed as a sublay.28 With even longer follow-up to 5 years, Jänes et al reported a 13.3% hernia rate using a sublay approach, compared with 81% in controls.26 Parastomal hernia rates in other prospective trials mirror these findings, with hernia detected at a twofold to threefold greater rate in control arms compared with those with mesh reinforcement at the aperture. Accrual has completed for the large, multicenter, randomized controlled Dutch PREVENT trial examining sublay lightweight polypropylene mesh, and the results are eagerly awaited.30

More recently, a multicenter, randomized trial from Finland examined parastomal hernia rates after APR.31 In this study, surgeons placed a dual-component composite mesh intra-abdominally, deep to the peritoneum. There was no difference in CT-detected herniation, but fewer clinically significant hernias were seen in the mesh reinforcement group (14.3 vs. 32.3% in controls, p < 0.05). This study demonstrates the important distinction between clinically and radiographically identified stomal hernias. Other authors demonstrated that CT-detected parastomal hernias occur in over 93% of standard stoma creations and even 50% of mesh-reinforced ostomies.15 Given the inherent risk of re-herniation and lack of a clearly superior approach to repair, surgeons should be guided by patient symptoms rather than appearance on imaging alone when making decisions for parastomal hernia repair.

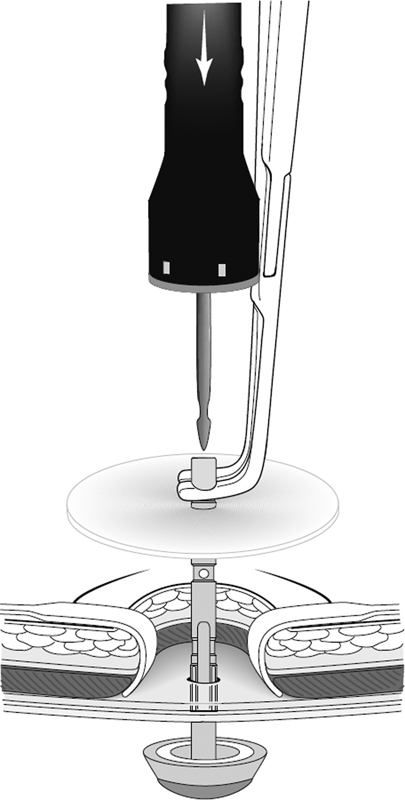

Stapled Mesh Reinforcement

An exciting and novel approach to primary prevention of parastomal hernia is the stapled mesh stoma reinforcement technique (also known as SMART).32 33 As described by Williams et al, this approach relies on biologic mesh stapled to the posterior rectus fascia using a purpose-designed stapler similar to the standard end-to-end anastomotic (EEA) stapler (Fig. 2). By using the stapler, a reinforced stoma trephine is created of precise diameter, ranging from 17 to 30 mm. The mesh is then secured circumferentially to the anterior rectus fascia with interrupted sutures. Preliminary data comparing patients treated with SMART to nonrandomized contemporary controls showed a significantly lower parastomal hernia rate using this novel technique (19 vs. 73%, p < 0.04).32 Whether this approach yields durable results or the use of synthetic mesh would improve outcomes even further awaits further investigation.

Fig. 2.

Creation of an ostomy trephine via the stapled mesh stoma reinforcement technique (SMART). (Reprinted with permission from Williams et al.32)

Surgical Hernia Repair

The success of parastomal hernia repair depends not only on surgical technique but also on appropriate patient selection. It bears repeating that the majority of parastomal hernias are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic and do not require operative repair. The most common symptoms attributable to parastomal hernias include obstructive episodes, pain, poor cosmesis/bulging, and difficulties in pouching the stoma resulting in appliance leakage and subsequent skin complications. Even in these patients, however, the majority can be treated with conservative management. A change in the type of appliance, the use of skin protectants, and/or a stoma belt can go a long way in managing symptoms associated with parastomal hernias. Consultation with or the regular use of a wound ostomy care nurse has been shown to significantly improve patients' quality of life and reduce the rate of stoma appliance leakage.3 34 35 Thus, while up to 50% of patients with a stoma will develop a parastomal hernia, with the appropriate use of conservative management, only 30% of patients with a parastomal hernia will have symptoms severe enough to eventually require operative repair.36

A variety of techniques have been described for the surgical repair of parastomal hernias, reflecting the fact that it is a difficult problem to solve surgically and associated with a significant recurrence rate. Parastomal hernia repairs can be broadly divided into two types: nonmesh and mesh repairs. Nonmesh repairs include primary suture repair of the hernia defect and stoma relocation. Urgent or emergent parastomal hernia repair is reserved for hernias associated with acute, nonresolving bowel obstruction, incarceration, or strangulation. Nonelective repairs were recently shown to have a higher rate of recurrence and reoperation than elective repair, emphasizing the importance of timely elective repair in symptomatic patients whenever possible.37 No randomized controlled trials have been performed comparing different methods of parastomal hernia repair, and the literature consists primarily of single institution series with relatively small numbers describing outcomes using one type of repair and subsequent meta-analyses of these series.

Nonmesh Repairs

The two primary types of nonmesh repairs of parastomal hernias are primary suture repair of the fascial defect and stoma relocation. They are both included here primarily to emphasize that the use of either type of repair should largely be avoided in the elective setting. As the name implies, primary suture repair involves a local parastomal incision, reduction of the hernia contents, and closure of the fascial defect using absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures.2 Its advantages include technical simplicity and the avoidance of laparotomy. Primary repair is associated with a postoperative complication rate of approximately 20%, with half of these complications being surgical site infections.38 39 40 41 42 43 Its Achilles' heel, however, is an exceedingly high recurrence rate, ranging from 45 to 75% in the literature, with one report demonstrating 100% recurrence rate in patients undergoing second parastomal hernia repair.43 44 Accordingly, this technique should be reserved only for the rare patient with a small defect in whom there is a strong desire to avoid mesh placement or laparotomy.

Stoma relocation was initially described as an alternative to primary suture repair with initial reports showing lower recurrence rates.43 However, relocation requires laparotomy, and more importantly it “uses up” a potential stoma site that may be needed later in extenuating or emergency situations. Furthermore, subsequent studies with longer follow-up have demonstrated significant rates of hernia formation at the prior stoma site and the new stoma site (∼50% each) as well as at the midline incision.2 36 43 45 46 47 Stoma relocation may be necessary for the repair of very large parastomal hernias because the resultant soft tissue defect that remains after hernia sac reduction will lead to ill-fitting stoma appliances. If stoma relocation is required, it should be performed on the opposite side of the midline because of an increased risk of hernia recurrence if the stoma is relocated on the same side.47

Mesh Repairs

The success of prosthetic mesh in reducing recurrence rates after other types of hernia repair spurred its application in parastomal hernia repair. Rosin and Bonardi first introduced and demonstrated the safety and efficacy of mesh repair for parastomal hernia.48 Since then, an abundance of evidence has emerged that demonstrates lower recurrence rates with mesh repair of parastomal hernias (5–15%) compared with the aforementioned nonmesh repairs.39 Furthermore, the fear of mesh infection and erosion has proved to be unfounded, with reported mesh infection rates between 2 and 3% and overall wound infection rates of 4%, which is lower than that reported for primary suture repair.39 These results have made mesh repair of parastomal hernias the preferred approach. Several different mesh repairs of parastomal hernias have been described, with the significant variables being the type of mesh used, the location of mesh placement, and surgical approach. Pertinent issues regarding these variables are discussed below.

Polypropylene was initially used in parastomal hernia repair. Its open mesh structure that causes strong ingrowth into adjacent fascia also results in dense adhesions to adjacent bowel and viscera with subsequent risk of mesh erosion and bowel fistulization. For these concerns, polypropylene mesh has fallen out of favor and has largely been replaced by polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or biologic meshes. PTFE is a soft, inert material that does not tend to form adhesions to underlying bowel. Its disadvantage is that the mesh shrinks significantly after placement, possibly resulting in higher rates of recurrence. Composite meshes using both polypropylene and PTFE have been designed to combine the advantageous properties of both materials. There has been no difference detected in wound or mesh infections between polypropylene and PTFE when used in parastomal hernia repair.39 More recently, the use of collagen-based biologic mesh for parastomal hernias has drawn interest due to their resistance to infection in a potentially contaminated field. However, a recent review demonstrates no difference in outcomes in terms of wound or mesh infection and hernia recurrence between biologic mesh and synthetic mesh in the repair of parastomal hernias.49 Thus, at present, the routine use of biologic mesh in the repair of parastomal hernias cannot be recommended due to cost efficacy. However, we would note that there may be specific situations in which the use of biologic mesh may be beneficial, though there is no evidence-based data to support this. The first is for the repair of parastomal hernias in patients with Crohn disease, where there is always the potential to develop fistulizing disease, and permanent synthetic intra-abdominal mesh may serve as a nidus for bowel fistulization and erosion. The second is when a full-thickness enterotomy is created during the dissection for repair of the parastomal hernia. In this situation, the use of synthetic mesh may not be advisable due to risk of mesh infection, and options include repair of enterotomy and closure, with subsequent delayed repair of the hernia, or the use of biologic mesh to repair the hernia, which is the authors' preference. Finally, emergency operation for parastomal hernia complicated by incarceration and intestinal ischemia may be another indication for the use of biologic mesh.

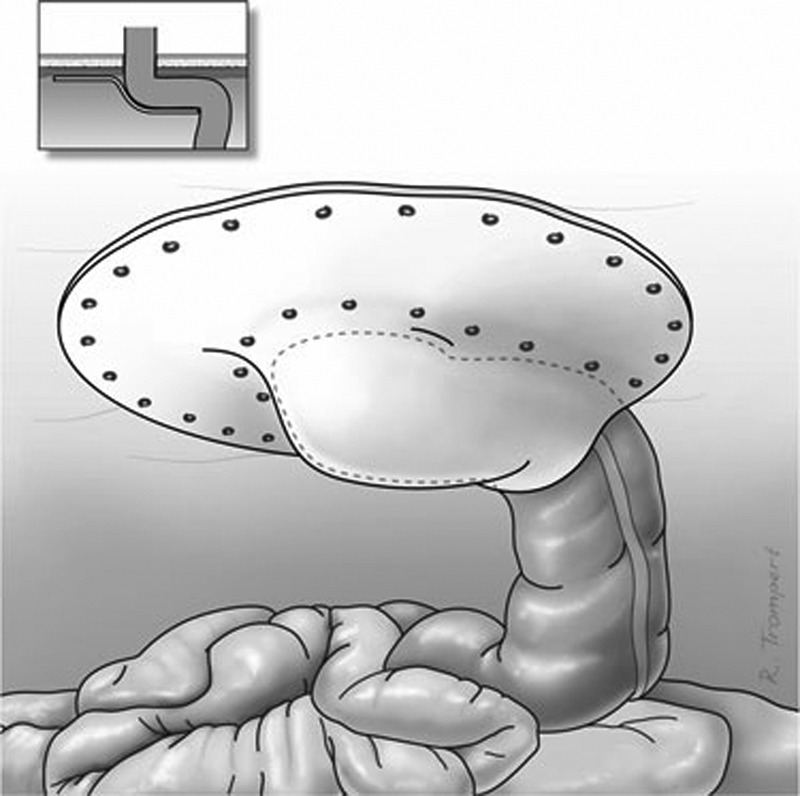

Similar to prophylactic placement during stoma formation, mesh for repair can be placed in different anatomic positions. There are no randomized controlled trials comparing different mesh locations, but recent reviews demonstrate no difference in wound or mesh infection between any of the anatomic mesh positions.39 44 There does appear to be higher recurrence rate with onlay mesh position (15–17%) compared with the sublay or underlay position (7–10%), although this did not achieve statistical significance.39 These differences are likely due to the biomechanical advantage of the sublay or underlay positions, where intra-abdominal pressure supports fixation of the mesh against the fascia. While technically more complex, the sublay repair also affords the additional advantage of not having any mesh exposed to the bowel. When mesh is placed in the intraperitoneal location, two types of mesh repair have been described: the keyhole repair and the Sugarbaker repair. In the keyhole repair, a 2- to 3-cm keyhole is fashioned in the mesh through which the stoma passes. Care must be taken to ensure this keyhole is neither too small (causing stomal obstruction) nor too large (increasing risk of recurrence). The Sugarbaker repair, first described in 1985, involves placement of mesh to cover the entire hernia defect with 3- to 5-cm overlap.50 The bowel loop that forms the stoma is then passed over the lateral edge of the mesh for at least 5 cm before entering the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 3). Although no direct comparisons have been performed, most reports consistently demonstrate lower recurrence rates for the Sugarbaker repair compared with the keyhole repair, with no other differences with respect to wound or mesh infection or other postoperative morbidity.5 39 51 52 53 This is likely due to mesh shrinkage with subsequent expansion of the central hole in the keyhole repair. Most recently, a sandwich technique has been described which utilizes two pieces of mesh placed in the underlay position: the first mesh is placed in a keyhole fashion followed by a second larger piece of mesh placed in a Sugarbaker fashion. In an observational study of 47 patients, a recurrence rate of 2.1% was noted after a median follow-up of 20 months.54 55

Fig. 3.

The laparoscopic Sugarbaker (underlay) repair depicting placement of the mesh with lateralization of the colon leading to the stoma aperture. (Reprinted under open access from Hansson et al.52)

Both laparoscopic and open approaches to parastomal hernia have been described. While two earlier studies could not demonstrate differences in morbidity or mortality between the laparoscopic and open approaches, the most recent study using the NSQIP (National Surgical Quality Improvement Program) database demonstrates shorter operative times and shorter length of hospital stay with reduced overall morbidity and surgical site infections with a laparoscopic approach.39 41 56 The laparoscopic approach has the additional advantage of detecting and treating other abdominal hernias, whereas open repair requires not only repair of the parastomal hernia, but also, hernia experts would advocate, mesh coverage of the entire laparotomy incision. Although there was initial concern over unrecognized enterotomies with a laparoscopic approach, inadvertent enterotomy is observed in 4% of laparoscopic repairs, which is similar to that observed in patients undergoing repeat laparotomy.39 57

The quality of the current literature regarding parastomal hernia repairs hampers the ability to make firm recommendations regarding the optimal repair. The majority of the literature consists of small series of parastomal hernia repairs and systematic reviews and meta-analyses. In general, mesh repairs should be preferred to nonmesh repairs, and among mesh repairs, either a sublay mesh repair or intraperitoneal Sugarbaker repair using synthetic mesh offers the lowest recurrence rate with similar rate of perioperative morbidity when compared with other repairs. The laparoscopic approach appears to have some short-term benefits, although no studies have compared long-term outcomes between laparoscopic and open parastomal hernia repairs. The authors' preference is to perform laparoscopic Sugarbaker repair when possible using PTFE. Additional study in parastomal hernia should focus on high-quality prospective comparative trials to provide further clarity regarding the optimal method of repair.

Conclusion

Parastomal hernias remain a vexing problem that will likely continue to increase along with the numbers of new ostomies. The solution to this problem likely lies with prevention, as several techniques such as extraperitoneal tunneling and stoma aperture reinforcement with mesh have been shown to reduce (but not eliminate) subsequent herniation. Every effort should be made to perform a durable repair prior to relocating the stoma to preserve future surgical options. When repair is undertaken, generous mesh underlay seems to be the best approach, although head-to-head comparative studies are lacking. Future patients will clearly benefit from better outcomes-oriented research, and the development of novel bioprosthetic–synthetic composites and standardized robotic repairs are exciting possibilities.

References

- 1.Hendren S, Hammond K, Glasgow S C. et al. Clinical practice guidelines for ostomy surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(4):375–387. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carne P W, Robertson G M, Frizelle F A. Parastomal hernia. Br J Surg. 2003;90(7):784–793. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kald A, Juul K N, Hjortsvang H, Sjödahl R I. Quality of life is impaired in patients with peristomal bulging of a sigmoid colostomy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(5):627–633. doi: 10.1080/00365520701858470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scarpa M, Ruffolo C, Boetto R, Pozza A, Sadocchi L, Angriman I. Diverting loop ileostomy after restorative proctocolectomy: predictors of poor outcome and poor quality of life. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(9):914–920. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aquina C T, Iannuzzi J C, Probst C P. et al. Parastomal hernia: a growing problem with new solutions. Dig Surg. 2014;31(4–5):366–376. doi: 10.1159/000369279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sjödahl R, Anderberg B, Bolin T. Parastomal hernia in relation to site of the abdominal stoma. Br J Surg. 1988;75(4):339–341. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800750414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans M D, Thomas C, Beaton C, Williams G L, McKain E S, Stephenson B M. Lowering the incidence of stomal herniation: further follow up of the lateral rectus abdominis positioned stoma. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(6):716–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephenson B M, Evans M D, Hilton J, McKain E S, Williams G L. Minimal anatomical disruption in stoma formation: the lateral rectus abdominis positioned stoma (LRAPS) Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(10):1049–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardt J, Meerpohl J J, Metzendorf M I, Kienle P, Post S, Herrle F. Lateral pararectal versus transrectal stoma placement for prevention of parastomal herniation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD009487. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009487.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliot-Smith A, Painter N S. Experiences with extraperitoneal colostomy and ileostomy. Gut. 1961;2:360–362. doi: 10.1136/gut.2.4.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goligher J C. Extraperitoneal colostomy or ileostomy. Br J Surg. 1958;46(196):97–103. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004619602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Londono-Schimmer E E, Leong A P, Phillips R K. Life table analysis of stomal complications following colostomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37(9):916–920. doi: 10.1007/BF02052598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamada M, Ozaki K, Muraoka G, Kawakita N, Nishioka Y. Permanent end-sigmoid colostomy through the extraperitoneal route prevents parastomal hernia after laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(9):963–969. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31825fb5ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lian L, Wu X R, He X S. et al. Extraperitoneal vs. intraperitoneal route for permanent colostomy: a meta-analysis of 1,071 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27(1):59–64. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.López-Cano M, Lozoya-Trujillo R, Quiroga S. et al. Use of a prosthetic mesh to prevent parastomal hernia during laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection: a randomized controlled trial. Hernia. 2012;16(6):661–667. doi: 10.1007/s10029-012-0952-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nastro P, Knowles C H, McGrath A, Heyman B, Porrett T R, Lunniss P J. Complications of intestinal stomas. Br J Surg. 2010;97(12):1885–1889. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammond T M, Huang A, Prosser K, Frye J N, Williams N S. Parastomal hernia prevention using a novel collagen implant: a randomised controlled phase 1 study. Hernia. 2008;12(5):475–481. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0383-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Figel N A Rostas J W Ellis C N Outcomes using a bioprosthetic mesh at the time of permanent stoma creation in preventing a parastomal hernia: a value analysis Am J Surg 20122033323–326., discussion 326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleshman J W Beck D E Hyman N Wexner S D Bauer J George V; PRISM Study Group. A prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled study of non-cross-linked porcine acellular dermal matrix fascial sublay for parastomal reinforcement in patients undergoing surgery for permanent abdominal wall ostomies Dis Colon Rectum 2014575623–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayer I, Kyzer S, Chaimoff C. A new approach to primary strengthening of colostomy with Marlex mesh to prevent paracolostomy hernia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1986;163(6):579–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berger D. Prevention of parastomal hernias by prophylactic use of a specially designed intraperitoneal onlay mesh (Dynamesh IPST) Hernia. 2008;12(3):243–246. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hauters P, Cardin J L, Lepere M, Valverde A, Cossa J P, Auvray S. Prevention of parastomal hernia by intraperitoneal onlay mesh reinforcement at the time of stoma formation. Hernia. 2012;16(6):655–660. doi: 10.1007/s10029-012-0947-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marimuthu K, Vijayasekar C, Ghosh D, Mathew G. Prevention of parastomal hernia using preperitoneal mesh: a prospective observational study. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8(8):672–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vijayasekar C, Marimuthu K, Jadhav V, Mathew G. Parastomal hernia: is prevention better than cure? Use of preperitoneal polypropylene mesh at the time of stoma formation. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12(4):309–313. doi: 10.1007/s10151-008-0441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jänes A, Cengiz Y, Israelsson L A. Randomized clinical trial of the use of a prosthetic mesh to prevent parastomal hernia. Br J Surg. 2004;91(3):280–282. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jänes A Cengiz Y Israelsson L A Preventing parastomal hernia with a prosthetic mesh: a 5-year follow-up of a randomized study World J Surg 2009331118–121., discussion 122–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gögenur I, Mortensen J, Harvald T, Rosenberg J, Fischer A. Prevention of parastomal hernia by placement of a polypropylene mesh at the primary operation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(8):1131–1135. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0615-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serra-Aracil X, Bombardo-Junca J, Moreno-Matias J. et al. Randomized, controlled, prospective trial of the use of a mesh to prevent parastomal hernia. Ann Surg. 2009;249(4):583–587. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819ec809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shabbir J, Chaudhary B N, Dawson R. A systematic review on the use of prophylactic mesh during primary stoma formation to prevent parastomal hernia formation. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(8):931–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brandsma H T, Hansson B M, Aufenacker T J. et al. Prophylactic mesh placement to prevent parastomal hernia, early results of a prospective multicentre randomized trial. Hernia. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10029-015-1427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vierimaa M, Klintrup K, Biancari F. et al. Prospective, randomized study on the use of a prosthetic mesh for prevention of parastomal hernia of permanent colostomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(10):943–949. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams N S, Hotouras A, Bhan C, Murphy J, Chan C L. A case-controlled pilot study assessing the safety and efficacy of the Stapled Mesh stomA Reinforcement Technique (SMART) in reducing the incidence of parastomal herniation. Hernia. 2015;19(6):949–954. doi: 10.1007/s10029-015-1346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams N S, Nair R, Bhan C. Stapled mesh stoma reinforcement technique (SMART)—a procedure to prevent parastomal herniation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93(2):169. doi: 10.1308/003588411X12851639107313c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erwin-Toth P Thompson S J Davis J S Factors impacting the quality of life of people with an ostomy in North America: results from the Dialogue Study J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2012394417–422., quiz 423–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Randall J, Lord B, Fulham J, Soin B. Parastomal hernias as the predominant stoma complication after laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22(5):420–423. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31825d36d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Israelsson L A. Preventing and treating parastomal hernia. World J Surg. 2005;29(8):1086–1089. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7973-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helgstrand F, Rosenberg J, Kehlet H, Jorgensen L N, Wara P, Bisgaard T. Risk of morbidity, mortality, and recurrence after parastomal hernia repair: a nationwide study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(11):1265–1272. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182a0e6e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al Shakarchi J, Williams J G. Systematic review of open techniques for parastomal hernia repair. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18(5):427–432. doi: 10.1007/s10151-013-1110-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansson B M, Slater N J, van der Velden A S. et al. Surgical techniques for parastomal hernia repair: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):685–695. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824b44b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLemore E C, Harold K L, Efron J E, Laxa B U, Young-Fadok T M, Heppell J P. Parastomal hernia: short-term outcome after laparoscopic and conventional repairs. Surg Innov. 2007;14(3):199–204. doi: 10.1177/1553350607307275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pastor D M, Pauli E M, Koltun W A, Haluck R S, Shope T R, Poritz L S. Parastomal hernia repair: a single center experience. JSLS. 2009;13(2):170–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riansuwan W, Hull T L, Millan M M, Hammel J P. Surgery of recurrent parastomal hernia: direct repair or relocation? Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(7):681–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubin M S Schoetz D J Jr Matthews J B Parastomal hernia. Is stoma relocation superior to fascial repair? Arch Surg 19941294413–418., discussion 418–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hotouras A, Murphy J, Thaha M, Chan C L. The persistent challenge of parastomal herniation: a review of the literature and future developments. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(5):e202–e214. doi: 10.1111/codi.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cingi A, Cakir T, Sever A, Aktan A O. Enterostomy site hernias: a clinical and computerized tomographic evaluation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(10):1559–1563. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0681-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guzmán-Valdivia G. Incisional hernia at the site of a stoma. Hernia. 2008;12(5):471–474. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0378-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allen-Mersh T G, Thomson J P. Surgical treatment of colostomy complications. Br J Surg. 1988;75(5):416–418. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800750507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosin J D, Bonardi R A. Paracolostomy hernia repair with Marlex mesh: a new technique. Dis Colon Rectum. 1977;20(4):299–302. doi: 10.1007/BF02586428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Slater N J, Hansson B M, Buyne O R, Hendriks T, Bleichrodt R P. Repair of parastomal hernias with biologic grafts: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(7):1252–1258. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1435-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sugarbaker P H. Peritoneal approach to prosthetic mesh repair of paraostomy hernias. Ann Surg. 1985;201(3):344–346. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198503000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Asif A, Ruiz M, Yetasook A. et al. Laparoscopic modified Sugarbaker technique results in superior recurrence rate. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(12):3430–3434. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hansson B M, Morales-Conde S, Mussack T, Valdes J, Muysoms F E, Bleichrodt R P. The laparoscopic modified Sugarbaker technique is safe and has a low recurrence rate: a multicenter cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(2):494–500. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2464-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mizrahi H, Bhattacharya P, Parker M C. Laparoscopic slit mesh repair of parastomal hernia using a designated mesh: long-term results. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(1):267–270. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1866-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berger D, Bientzle M. Laparoscopic repair of parastomal hernias: a single surgeon's experience in 66 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(10):1668–1673. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9028-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berger D, Bientzle M. Polyvinylidene fluoride: a suitable mesh material for laparoscopic incisional and parastomal hernia repair! A prospective, observational study with 344 patients. Hernia. 2009;13(2):167–172. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Halabi W J, Jafari M D, Carmichael J C. et al. Laparoscopic versus open repair of parastomal hernias: an ACS-NSQIP analysis of short-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(11):4067–4072. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fevang B T, Fevang J, Lie S A, Søreide O, Svanes K, Viste A. Long-term prognosis after operation for adhesive small bowel obstruction. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):193–201. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000132988.50122.de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]