Abstract

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are broadly expressed in eukaryotic cells, but their molecular mechanism in human disease remains obscure. Here we show that circular antisense non-coding RNA in the INK4 locus (circANRIL), which is transcribed at a locus of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease on chromosome 9p21, confers atheroprotection by controlling ribosomal RNA (rRNA) maturation and modulating pathways of atherogenesis. CircANRIL binds to pescadillo homologue 1 (PES1), an essential 60S-preribosomal assembly factor, thereby impairing exonuclease-mediated pre-rRNA processing and ribosome biogenesis in vascular smooth muscle cells and macrophages. As a consequence, circANRIL induces nucleolar stress and p53 activation, resulting in the induction of apoptosis and inhibition of proliferation, which are key cell functions in atherosclerosis. Collectively, these findings identify circANRIL as a prototype of a circRNA regulating ribosome biogenesis and conferring atheroprotection, thereby showing that circularization of long non-coding RNAs may alter RNA function and protect from human disease.

Circular RNAs are widely expressed in eukaryotic cells but their functions and mechanisms of action are still being elucidated. Here the authors show that circANRIL modulates rRNA maturation and confers protection again atherosclerosis.

Circular RNAs are widely expressed in eukaryotic cells but their functions and mechanisms of action are still being elucidated. Here the authors show that circANRIL modulates rRNA maturation and confers protection again atherosclerosis.

Deep sequencing combined with novel bioinformatics approaches led to the discovery that a significant portion of the human transcriptome is spliced into RNA loops1,2,3. These circular RNAs (circRNAs) do not retain the exon order defined by their genomic sequence and are thought to originate from non-canonical splicing of a 5′ splice site to an upstream 3′ splice site4. Recent studies suggest that exon circularization may depend, in part, on inverted repeats or flanking intronic complementary sequences5,6 but little is known about the functions of these highly stable RNA forms.

Before the finding that circRNAs are abundantly transcribed in humans, there were few reports of circRNAs in mammals. One of the earliest examples is the sex determining region of Chr Y (Sry) gene in mice, the Y chromosome encoded master regulator of the testis-determining pathway7. Sry may be expressed as circular and linear transcripts and circularization is thought to be a mechanism to escape translation7,8. Sry was also shown to serve as a competing endogenous RNA of miRNA-138 (ref. 9), and a similar ‘miRNA sponging' function has been demonstrated for a transcript antisense to cerebellar degeneration related protein 1 (CDR1as/ciRS-7)2,9. CDR1as contains ∼70 binding sites for miR-7 and acts to suppress miR-7 activity, resulting in increased levels of miR-7 target genes and functions2,9. However, only few circRNAs harbour multiple binding sites for miRNAs10, suggesting that these abundant RNAs may have other unknown regulatory functions.

Previous work indicated that the long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) ANRIL(CDKN2B-AS1), which is transcribed at the cardiovascular disease risk locus on chromosome 9p21 (refs 11, 12, 13), is capable of forming RNA circles14, yet the functional relevance in human health and disease is unknown. ANRIL is differentially expressed by the genotype at 9p21 (for review see ref. 15) and increased linear ANRIL (linANRIL) was associated with increased atherosclerosis16. Recent studies suggest an important role for Alu elements in epigenetic gene regulation by linANRIL17. These Alu repeats and distal ANRIL exons are not conserved in non-primate species18, suggesting a primate-specific gain of function of this lncRNA. Here we identify a molecular effector mechanism of circular ANRIL (circANRIL) using proteomic screening, bioinformatics and functional studies. We demonstrate that circANRIL regulates the maturation of precursor ribosomal RNA (pre-rRNA), thus controlling ribosome biogenesis and nucleolar stress. In concert, circANRIL confers disease protection by modulating apoptosis and proliferation in human vascular cells and tissues, which are key cellular functions in atherosclerosis.

Results

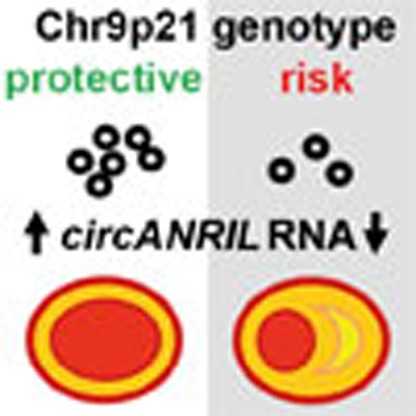

Association of circANRIL with atheroprotection at human 9p21

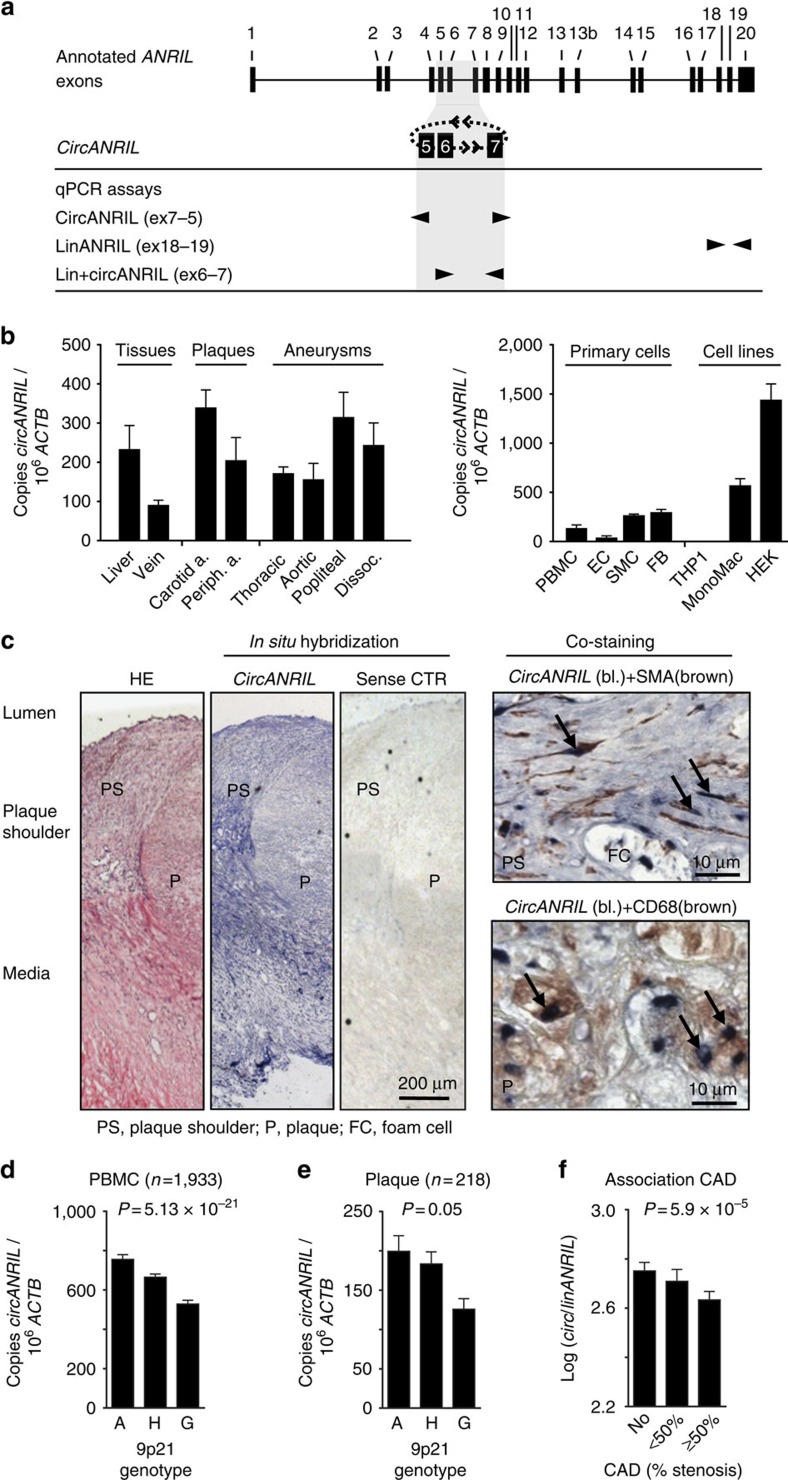

We systematically investigated the exon structure of circANRIL in human cell lines and primary cells (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). Using outward-facing primers and PCR analysis of reverse-transcribed RNA, we observed several species of circANRIL isoforms. The predominant circANRIL isoform consisted of exons 5, 6 and 7, where exon 7 was non-canonically spliced to exon 5 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). We focused on this isoform for detailed functional characterization and further refer to it as circANRIL. CircANRIL was expressed in both healthy and diseased human vascular tissues, as well as smooth muscle cells (SMC) and monocyte/macrophages (Fig. 1b), which play an important role in atherogenesis. CircANRIL levels were relatively low compared with abundant housekeeping mRNAs such as actin beta (ACTB; Fig. 1b), but comparable to the levels of other human circular RNAs such as the previously described CDR1as2 or circular HPRT1 (circHPRT1), which was identified in the present study (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Nevertheless, circANRIL RNA levels were on average 9.7-fold higher than levels of linANRIL RNA when we analysed a panel of different human cell types and tissues (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b). CircANRIL was also more stable than linANRIL (Supplementary Fig. 3). The latter is in line with previous reports on other circular RNAs1,19. To determine the spatial distribution of circANRIL expression in the context of vascular atherogenesis, we performed RNA in situ hybridization using a circANRIL-specific probe (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 4). We detected circANRIL in SMC and in CD68-positive macrophages in human atherosclerotic plaques (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1. CircANRIL expression in human vascular tissue and association with atheroprotection at 9p21.

(a) Schematic of circANRIL at 9p21 and qPCR assays for isoform specific quantification. CircANRIL contains exons 5, 6 and 7. Exon 7 is non-canonically spliced to exon 5. (b) qPCR analysis of circANRIL expression in human tissues, primary cells and cell lines. Beta actin (ACTB), house-keeping gene; FB, adventitial fibroblasts; HEK, HEK-293 cell line; THP1 and MonoMac, human monocytic cell line. Analyses were done in RNA pools of at least three donors. (c) In situ hybridization of circANRIL in human atherosclerotic plaque and co-localization with smooth muscle actin (SMA)-positive cells and macrophages (CD68). Sense control (CTR)-negative control. Representative staining out of three biological replicates. (d) Association of circANRIL with 9p21 haplotypes in PBMC from CAD patients. Protective (A, n=498), heterozygote (H, n=979) and risk (G, n=456) haplotypes. (e) Association of circANRIL with 9p21 haplotypes A (n=49), H (n=114) and G (n=55) in endarterectomy specimens. (f) Association of circ/linANRIL ratio in PBMC with severity of CAD (No, n=745; <50% stenosis, n=392; ≥50% stenosis, n=747). Data are given as mean±s.e.m., and associations were calculated using robust linear regression models.

We next tested for an association of circANRIL expression with the 9p21 genotype in a large cohort of patients with different burden of coronary artery disease (CAD), as assessed by coronary angiography17,20. Carriers of the CAD-protective haplotype at 9p21 showed significantly increased expression of circANRIL in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC, n=1,933; 14% per protective A-allele; Fig. 1d) and whole blood (n=970; P=1.86 × 10−7; 27% per allele; associations were calculated using robust linear regression models). Differential expression was replicated in endarterectomy specimens, where each protective allele was associated with 13% higher circANRIL expression (Fig. 1e). Importantly, the direction of effects for circANRIL was inverse to the published results for linANRIL, which was downregulated in patients carrying the 9p21 protective genotype16,17. Consistent with these findings, circANRIL expression was inversely correlated with linANRIL expression in PBMC of the CAD cohort (r=−0.24; P=3.72 × 10−29; linear regression). We then tested for an association of circANRIL with CAD burden. Patients with high circANRIL expression developed less CAD (P=0.047; odds ratio=0.8; linear regression) and highest circANRIL/linANRIL ratios were found in patients free of CAD (P=5.9 × 10−5; odds ratio=0.75; Fig. 1f; linear regression). Calculated by a Mendelian randomization approach, the circANRIL/linANRIL ratio explained a significant part of the observed association of 9p21 with CAD (P=0.002; linear regression). This establishes a causal relationship between the genotype at 9p21, high circANRIL expression and CAD protection. Taken together, these data implied an atheroprotective role of circANRIL at 9p21, which was inverse to the previously reported proatherogenic function of its linear counterparts17.

CircANRIL controls apoptosis and cell proliferation in vitro

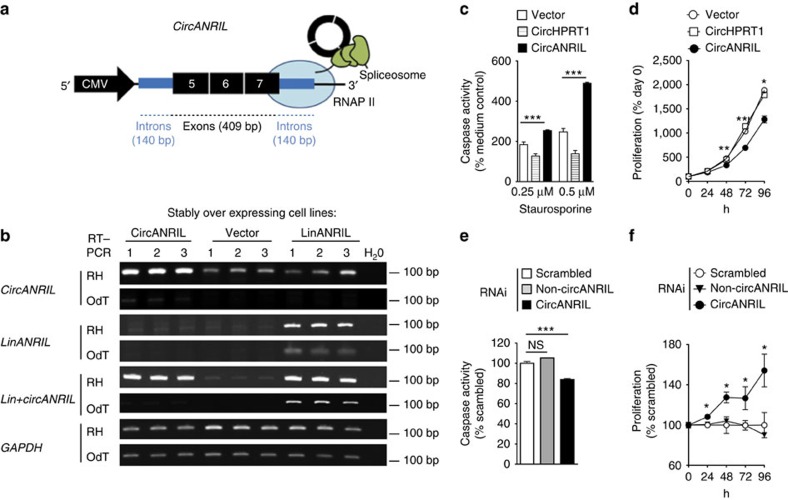

We next wanted to test whether circANRIL was biologically active and controlled cell functions related to atherosclerosis. To mimic increased levels of circANRIL RNA, as observed in patients that were protected from atherosclerosis, we set out to generate cell lines stably overexpressing the circANRIL RNA consisting of exons 5, 6 and 7. Since circularization of ANRIL was spliceosome-dependent (Supplementary Fig. 5), we predicted that flanking intronic sequences might be relevant for circularization and constructed a vector, where exonic sequences were surrounded by 140 bp intronic sequences 5′ of exon 5 and 3′ of exon 7 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 1). On the basis of this approach we succeeded to express circANRIL RNA in 12 of 30 (40%) stably transfected HEK-293 cells, which was validated by circANRIL-specific quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qPCR) (Fig. 2b). On average, stably overexpressing circANRIL cells had 16-fold higher circANRIL expression levels compared with endogenous circANRIL. For functional studies, we selected cell lines with a modest 3-fold overexpression to resemble a more physiological situation (Fig. 2c–f). Corroborating our previous results, measuring circANRIL RNA turnover rates following inhibition of RNA polymerase II transcription with actinomycin D, the overexpressed circANRIL was more stable than linANRIL (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Figure 2. Atherosclerosis-related cell functions in circANRIL-overexpressing cells.

(a) Schematic of the vector construct for circANRIL stable and transient overexpression. RNA polymerase II (RNAP II). (b) ANRIL isoform expression in HEK-293 cells that stably express circANRIL, linANRIL or empty vector (three biological replicates each). PCR of reverse-transcribed RNA, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), house-keeping gene; OdT, oligo(d)T primers; RH, random hexamer primers. (c) Apoptosis and (d) proliferation in HEK-293 cell line stably overexpressing circANRIL (pool of 3 biological replicates, and 8 and 12 technical replicates per condition, respectively), compared with overexpression of an unrelated circular RNA (circHPRT1). Apoptosis (e) and proliferation (f) after RNAi against circANRIL or non-circANRIL or scrambled (SCR) siRNA control. Quadruplicate measurements per condition. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. Comparison of multiple groups was done using analysis of variance, and Tukey was performed as post hoc test in c,e. Two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test in d,f. Data are given as mean±s.e.m.

Studies of key cell functions of atherogenesis in circANRIL-overexpressing cells revealed increased apoptosis (Fig. 2c) and decreased proliferation (Fig. 2d). Overexpression of the unrelated circular RNA circHPRT1 (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 1) did not trigger these effects (Fig. 2c,d), ruling out that proapoptotic and antiproliferative functions are generic roles of all circular RNAs. In further support for the specificity of the observed consequences of circANRIL overexpression, effects could be reversed by small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated downregulation of circANRIL RNA, but not by using linANRIL-specific or scrambled siRNA controls (Fig. 2e,f and Supplementary Fig. 8).

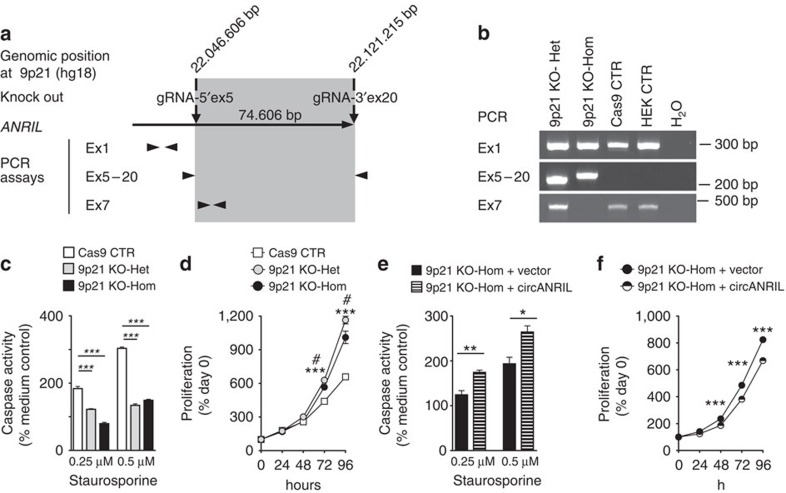

We next deleted exons 5–20 from the ANRIL locus in HEK-293 cells using CRISPR/Cas9 technology and established heterozygous and homozygous knockout cell lines (Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Table 2). Deletion of exons 5–20 impairs linANRIL RNA isoforms, which contain at least exons 5 and 6 (ref. 17). The deletion also affects several circANRIL isoforms, including the major isoform consisting of exons 5–7, which we are studying. Our analysis revealed that loss of ANRIL conferred a gene dosage-dependent reduction in apoptotic rate (Fig. 3c) and led to increased cellular proliferation (Fig. 3d). We stress that increased proliferation and reduced apoptosis cannot solely be ascribed to either deletion of linANRIL RNAs nor to deletion of circRNAs. For this reason, using an expression vector to restore circANRIL but not linANRIL expression in these cell lines, we re-expressed the major circANRIL isoform consisting of exons 5–7 in the knockout cell line that misses exons 5–20. We showed that presence of circANRIL alone was sufficient to increase cell apoptosis (Fig. 3e) and to reduce proliferation (Fig. 3f) indicating that circANRIL mediated its effects likely independent of linANRIL at 9p21. Together, this genetic analysis demonstrates that circANRIL is a physiologically relevant modulator of apoptosis and proliferative capacity.

Figure 3. Role of endogenous circANRIL on apoptosis and cell proliferation.

(a) Schematic of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of ANRIL in HEK-293 cells. Genomic regions encompassing exons (Ex) 5–20 were deleted. Arrowheads indicate location and orientation of primers used for genotyping. (b) PCR genotyping. Sequencing of PCR products from Ex5–20 assay validated successful deletion in mutant cell lines (Supplementary Table 2). (c) Apoptosis and (d) proliferation in heterozygous and homozygous ANRIL knockout or control cell lines. As control, Cas9 was overexpressed without guide RNAs (gRNAs). (e) Apoptosis and (f) proliferation in homozygous knockout cells following transient re-expression of circANRIL. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. (d) Heterozygous (***P<0.001) or homozygous (#P<0.05) ANRIL knockout versus control cell lines, respectively. Comparison of multiple groups was done using analysis of variance, and Tukey was performed as post hoc test in c. Two-tailed unpaired Student's t-tests were applied in d–f. Data are given as mean±s.e.m.

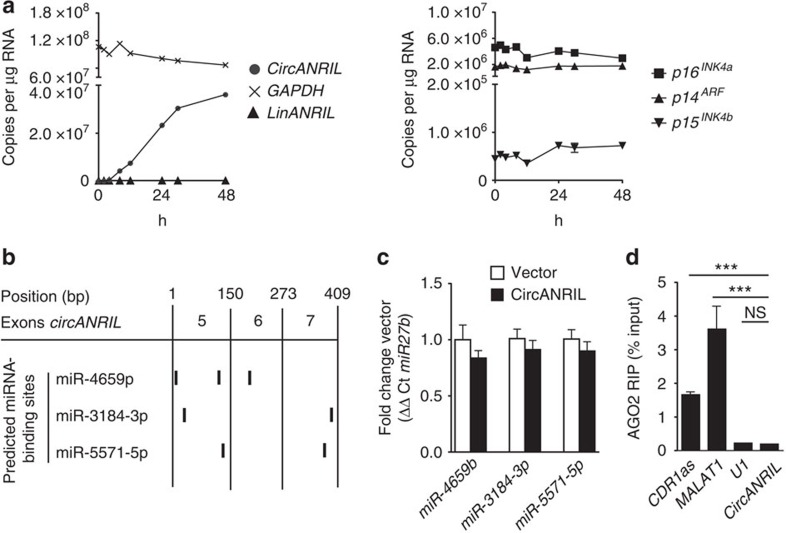

CircANRIL acts independent of CDKN2A/B and of miRNA sponging

Previous work suggested that ANRIL regulated the expression of the tumour suppressor genes cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors A and B (CDKN2A and B)21,22, located adjacent to ANRIL's genomic position. We therefore investigated whether circANRIL affected the expression of these genes, but we detected no significant changes (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, we observed that linANRIL remained unaffected by overexpressing circANRIL (Fig. 4a), excluding cis-regulation of 9p21 transcripts as molecular effector mechanism. Other work has shown that circRNAs, which were enriched for miRNA seeds, may serve as miRNA sponges2,9. However, we only identified a maximum of three binding sites for miR-4659a/b, miR-3184-3p and miR-5571-5p (Fig. 4b) in circANRIL. Moreover, expression of these miRNAs was not changed in circANRIL-overexpressing cells (Fig. 4c), and genome-wide expression arrays in circANRIL and control cells did not support an induction of miRNA-regulated networks (Supplementary Fig. 9; Gene Expression Omnibus GSE65392). In addition, circANRIL did not bind to argonaute 2 (AGO2; Fig. 4d) of the RNA-induced silencing complex, which is responsible for miRNA-dependent degradation of target RNAs. These data suggested that circANRIL controlled atheroprotective cell functions through a novel molecular mechanism, independent of cis-regulation at 9p21 and miRNA sponging.

Figure 4. CircANRIL does not regulate 9p21 protein-coding genes and lacks miRNA sponging activity.

(a) Overexpression of circANRIL in HEK-293 cells does not modulate endogenous linANRIL RNA abundance as measured by qPCR (left panel). Expression of p16INK4a and p14ARF, encoded by CDKN2A, and p15INK4b, encoded by CDKN2B, in circANRIL-overexpressing cells (right panel) (pool of three biological replicates, quadruplicate qPCR measurements). (b) Prediction of miRNA-binding sites in circANRIL using miRanda and TargetSpy algorithms. (c) miRNA expression normalized to miR-27b as measured by qPCR (four biological replicates, quadruplicate measurements). (d) RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) of AGO2. Analysis of precipitated RNAs: CDR1as, MALAT1, positive controls; U1, negative control (RIP was performed in a pool of three biological replicates, quadruplicate qPCR measurements). ***P<0.001. NS, not significantly different. (analysis of variance, and Tukey as post hoc test). Data are given as mean±s.e.m.

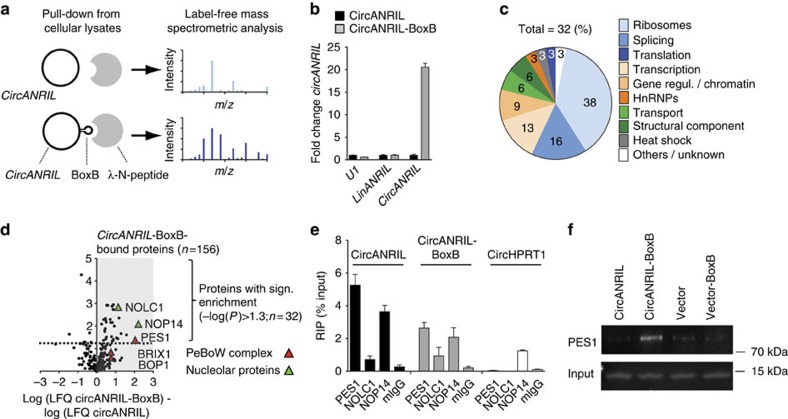

CircANRIL is a component of a pre-ribosomal assembly complex

Since linANRIL has protein-binding capacity17,21,22, we performed a proteomic screen to identify potential circANRIL-binding proteins (Fig. 5). To this end, we generated HEK-293 cell lines with stable overexpression of circANRIL engineered to contain RNA hairpin BoxB-sequences23 (circANRIL-BoxB; Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 1). This allowed capture of circANRIL-bound proteins in cellular lysates via high affinity interaction of the BoxB RNA hairpin with bacteriophage λ transcriptional antiterminator protein N (λN-peptide) coupled to beads (Fig. 5a–d). Circularization of circANRIL was not impaired by the insertion of BoxB-sequences (Supplementary Fig. 10). As controls for the capture, we used protein extracts from HEK-293 cell lines with stable overexpression of circANRIL without BoxB RNA hairpin sequences (Fig. 5a). On the basis of quantitative reverse transcription PCR analysis, we validated that circANRIL was highly enriched following bead-mediated capture (Fig. 5b), demonstrating that our isolation strategy was specific and selective. Capture experiments were performed in quadruplicates and we used 2 μg of precipitated protein from each of the two conditions for label-free mass spectrometric analyses. Here we detected 32 proteins with significant enrichment in extracts from circANRIL-BoxB-overexpressing cells compared with extracts from control cells (Fig. 5c,d and Supplementary Table 3). The majority of identified proteins was involved in ribosome biogenesis and assembly (38%) and regulation of RNA splicing (16%) (Fig. 5c) suggesting that circANRIL may play a role in these important cellular processes. Strongest binding was determined for nucleolar protein 14 (NOP14, Fig. 5d), which is involved in the formation of the nucleolar 40S ribosomal subunit24, and for pescadillo zebrafish homologue 1 (PES1, Fig. 5d), which is a component of the PES1–BOP1–WDR12 (PeBoW) complex. This complex is homologous to yeast Nop7-Erb1-Ymt1 (refs 25, 26) and a key regulator of large 60S ribosome subunit biogenesis27,28. The PeBoW complex assembles with pre-ribosomes and binds to precursor rRNA (pre-rRNA), thereby facilitating the processing of 47S pre-rRNA to mature 28S and 5.8S rRNA by exonucleases25,29,30. Block of proliferation 1 (BOP1), which was demonstrated to bind PES1 (refs 26, 30), was also present in circANRIL-BoxB extracts, as well as ribosome biogenesis protein BRX1 homologue (BRIX1) and nucleolar and coiled-body phosphoprotein 1 (NOLC1), two other PeBoW complex-associated proteins27 (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5. Identification of circANRIL-binding proteins.

(a) Schematic of λN-peptide-mediated capture of circANRIL-BoxB from cellular lysates of stably overexpressing HEK-293 cell lines, and label-free mass spectrometric quantification. Experiments were performed in a pool of three biological replicates (quadruplicate measurements). (b) Quantification of RNAs by qPCR after λN-peptide capture (quadruplicate measurements). (c) Summary of circANRIL-BoxB-bound proteins according to annotated (KEGG, GO) and published functions. (d) Volcano plot of label-free quantification (LFQ) of circANRIL-BoxB-bound proteins compared with circANRIL input control. (e) RIP of PES1, NOLC1, NOP14 and mouse IgG (mIgG) control (RIP was performed in a pool of three biological replicates, quadruplicate measurements). (f) Western blot of PES1 after λN-peptide-mediated circANRIL-BoxB capture using nuclear extracts from indicated cell lines.

To corroborate our mass spectrometric analysis by an independent method, we chose to analyse circANRIL–protein interactions by RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP). qPCR analysis after RIP revealed the interaction of circANRIL RNA with the PeBoW complex members PES1 and NOP14, where circANRIL binding to PES1 was the strongest interaction tested (Fig. 5e). PES1 binding was not detected for circularized HPRT1 (circHPRT1), indicating that the binding of circANRIL to PES1 was not due to a generic interaction of PES1 with all species of circular RNAs in a cell (Fig. 5e). λN-peptide-mediated pull-down of circANRIL-BoxB from nuclear extracts followed by western blotting validated circANRIL binding to PES1 protein (Fig. 5f) but not to NOP14. We therefore focused subsequent functional studies on PES1 as main circANRIL-interacting protein.

CircANRIL controls pre-rRNA maturation and nucleolar stress

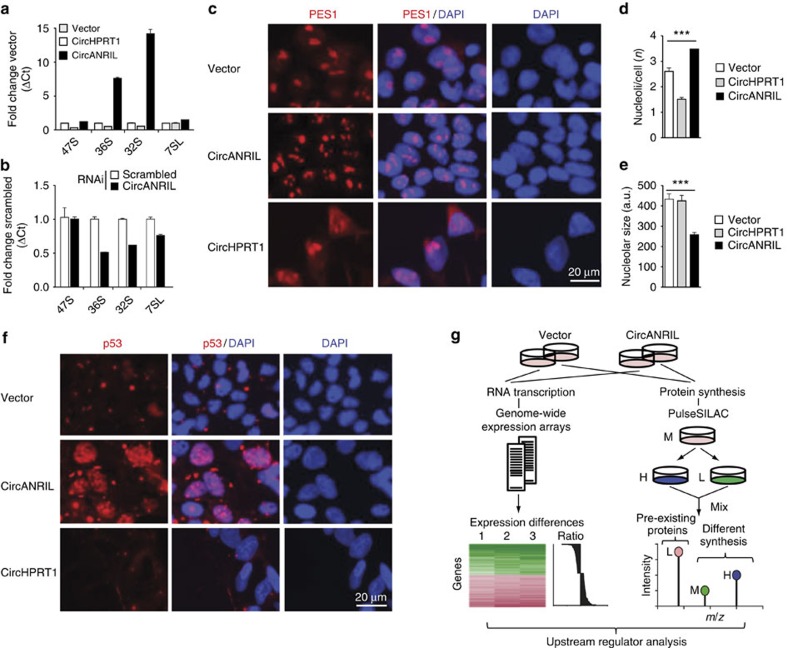

PES1 is essential for PeBoW complex function, and inhibition of this complex leads to accumulation of premature rRNA isoforms (Supplementary Fig. 11)29,30. Using isoform-specific qPCRs31, we detected a significant accumulation of 36S and 32S pre-rRNA in circANRIL-overexpressing HEK-293 cell lines but not in circHPRT1-overexpressing cells (Fig. 6a). Expression levels of 47S pre-rRNA and 7SL RNA, which is independently transcribed by RNA polymerase III, were not altered in either cell line (Fig. 6a). Corroborating results from our qPCR analysis, northern blotting revealed an accumulation of 32S and 36S pre-rRNAs in circANRIL-overexpressing cells (Supplementary Fig. 12). Effects on pre-rRNAs could be reversed by siRNA against circANRIL (Fig. 6b) implying that circANRIL negatively regulated PeBoW activity and rRNA maturation. This regulation of ribosome maturation is a previously undescribed function for circANRIL and a yet undescribed role for circular RNAs in general.

Figure 6. rRNA maturation defects and nucleolar stress in circANRIL-overexpressing cells.

(a) Relative quantification of pre-rRNA in circANRIL- or in circHPRT1-overexpressing HEK-293 cells using isoform-specific qPCRs (RNA from a pool of three biological replicates, quadruplicate measurements). (b) Pre-rRNA levels after RNAi against circANRIL or using scrambled siRNA control (quadruplicate measurements per condition). (c) Immunofluorescent staining of PES1 in circANRIL- or in circHPRT1-overexpressing HEK-293 or empty vector control cells. Quantification of (d) nucleoli and (e) nucleolar size in circANRIL- or circHPRT1-overexpressing or empty vector control cells (*** P<0.001). Data are given as mean±s.e.m. (analysis of variance, and Tukey as post hoc test). (f) Immunofluorescent staining of p53 (red) in circANRIL- or circHPRT1-overexpressing or empty vector control cells. (g) Schematic of transcriptome and proteome analyses in circANRIL-expressing HEK-293 cells and in control cells by genome-wide expression arrays and by pulseSILAC, respectively. For results of pathway analyses and procedure, see Supplementary Tables 4–6 and Methods section, respectively. L/M/H, light/medium/heavy medium.

It is well established that inhibition of rRNA maturation leads to impaired ribosome biogenesis and induction of nucleolar stress32, which may be evidenced by small nucleoli, nucleolar disorganization33 and p53 stabilization32,34. Indeed, immunofluorescent stainings of PES1 (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 13a) and BOP1 (Supplementary Fig. 13b) revealed significantly more (Fig. 6d) and smaller (Fig. 6e) nucleoli in circANRIL-overexpressing HEK-293 cells, providing evidence for increased nucleolar stress. Notably, we did not detect an increase in nucleolar number nor a decrease of nucleolar size when we stably overexpressed circHPRT1 (Fig. 6d,e), providing evidence for the specificity of the observed effects for circANRIL. Using immunofluorescent stainings, we also detected a significant accumulation of p53 in the nuclei of circANRIL-overexpressing cells (Fig. 6f and Supplementary Fig. 13c). Activation of p53 was further corroborated by proteomic analyses in cell cultures of circANRIL and control cell lines after pulse stable isotope labelling (pulseSILAC), as well as by transcriptome-wide RNA expression analyses (Fig. 6g), which indicated a significant activation of p53 signalling both, at the protein and at the mRNA level (Supplementary Tables 4–6; Gene Expression Omnibus GSE65392).

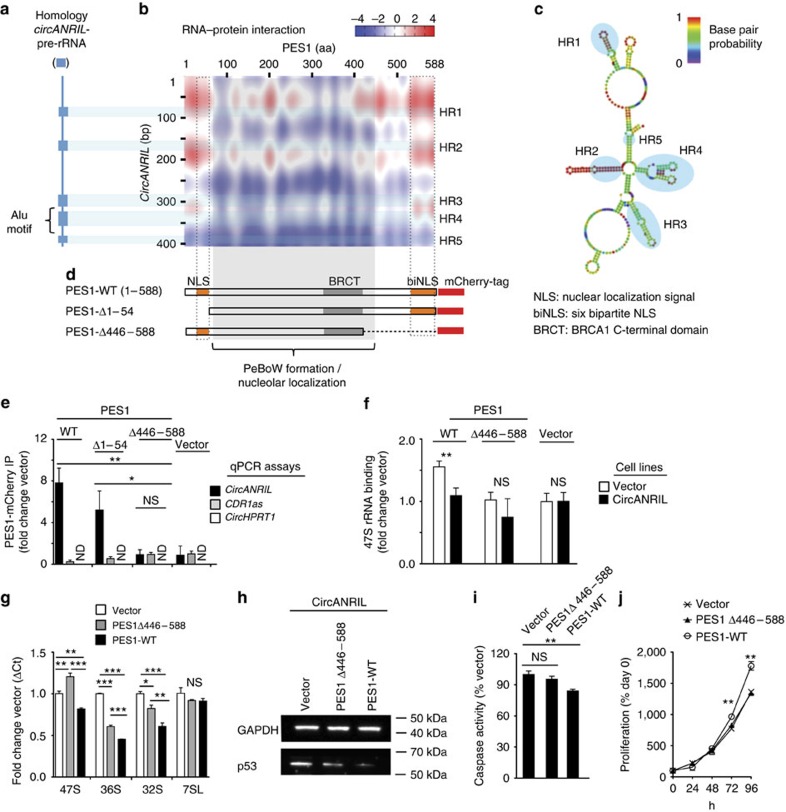

CircANRIL binding to PES1 prevents rRNA maturation

Although circANRIL and ribosomal RNA belong to different families of lncRNAs, we observed significant sequence homology (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Table 7). Since circANRIL (Fig. 5) and ribosomal RNA both bind to PES1 (ref. 25), we hypothesized that circANRIL occupied pre-rRNA-binding sites at PES1, thereby inhibiting exonuclease-mediated processing and maturation of ribosomal RNA. Using two independent algorithms for RNA–protein interaction, circANRIL-PES1 binding was predicted to be mediated through RNA domains with high pre-rRNA sequence homology (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Table 7) forming RNA stem loop structures (Fig. 7c), and through the N- and C-terminal domains of PES1 protein (Fig. 7d), respectively. These protein domains are enriched for lysine-rich amino-acid motifs with protein–RNA binding potential35 and have structural similarity to nuclear localization signals (NLSs). Previous work has shown that PES1's NLSs are not required for nucleolar localization of PES1 but important for PeBoW complex function26,29.

Figure 7. Molecular mechanism of circANRIL controlling PES1 function.

(a) Homology of circANRIL and precursor 47S rRNA (blue boxes) determined by BLASTn algorithm. (b) Prediction of RNA–protein interaction of circANRIL with PES1 using the catRAPID algorithm. Homology regions (HR1–HR5)—predicted RNA–protein interaction motifs in circANRIL. (c) Secondary structure prediction and HR1–5 of circANRIL using the Vienna RNA package69. (d) Schematic of PES1 with functional protein domains. Wild-type PES1 (PES1-WT) and two mutants lacking the 5′ (PES1Δ1–54) or the 3′ (PES1Δ446–588) lysine-rich NLSs. (e) Immunoprecipitation (IP) of PES1 isoforms from HEK-293 cells and quantification of RNA by qPCR (IP was performed in a pool of three biological replicates, quadruplicate measurements). (f) Pre-rRNA binding to PES1-WT and PES1Δ446–588 in circANRIL-overexpressing and control cells (IP was performed in a pool of three biological replicates, quadruplicate measurements). (g) Pre-rRNA and 7SL control RNA in circANRIL-expressing HEK-293 cells after transient PES1-WT or PES1Δ446–588 overexpression (pool of three biological replicates, quadruplicate measurements). (h) p53 western blot, (i), apoptosis and (j) cell proliferation in circANRIL-overexpressing HEK-293 cells with transient overexpression of PES1-WT or of PES1Δ446–588. Quadruplicate measurements per condition. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. NS, not significantly different. Analysis of variance, and Tukey as post hoc test in e,g and i. Two-tailed unpaired Student's t-tests were applied in f,j. Data are given mean±s.e.m.

To investigate whether circANRIL bound to PES1 at the predicted protein domains, we performed protein immunoprecipitation of full-length and truncated PES1 (PES1Δ1-54 or PES1Δ446–588, respectively; Fig. 7d,e, Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Table 8). We only detected circANRIL binding when the C-terminal PES1 protein domain (aa 446–588) was present (Fig. 7e). This domain was also required for 47S and 36S pre-rRNA binding and circANRIL prevented pre-rRNA binding to some extent (Fig. 7f and Supplementary Fig. 15). Importantly, full-length but not truncated PES1 restored rRNA maturation in circANRIL-expressing cells (Fig. 7g) and reduced p53 accumulation (Fig. 7h), apoptosis (Fig. 7i) and cellular proliferation (Fig. 7j).

Together, these data establish circANRIL as a molecular inhibitor of PES1 by binding at the C-terminal domain of PES1. This may, at least in part, explain the effects of circANRIL in rRNA maturation, nucleolar stress and atheroprotective cell functions.

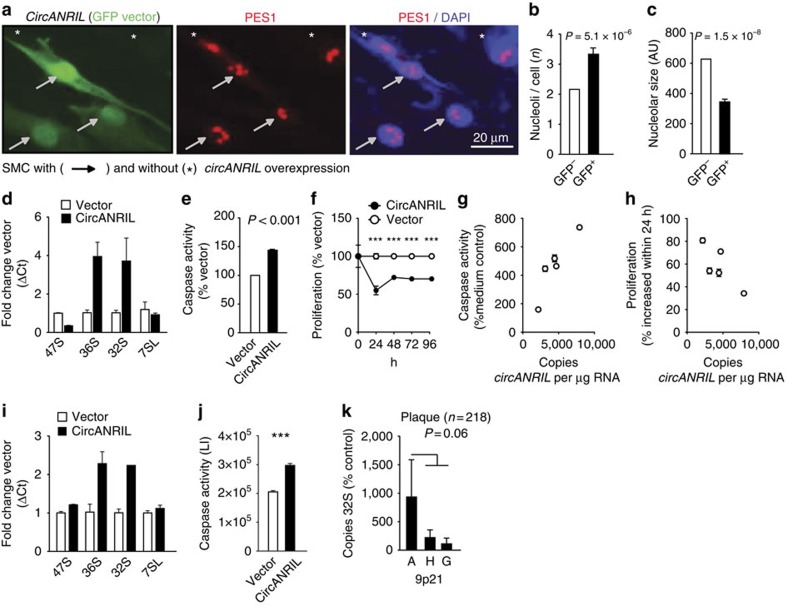

Translation of circANRIL molecular effects to human disease

ANRIL is evolutionary not conserved between species, and exons 5–7, which are contained in circANRIL, are primate-specific18. Consequently, no expression of circANRIL was detected in mouse tissues using qPCR preventing studies in mouse models. To translate our in vitro findings to a physiologically relevant in vivo context, we performed functional studies in human primary SMC and human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived macrophages and conducted association studies in human disease cohorts (Fig. 8). CircANRIL overexpression in SMC (Fig. 8a–f) increased the numbers of nucleoli (Fig. 8a,b), reduced nucleolar size (Fig. 8a,c), and led to an accumulation of pre-rRNAs (Fig. 8d). Consequently, circANRIL induced apoptosis (Fig. 8e) and decreased cell proliferation (Fig. 8f). Using SMC of different patients, we demonstrated that cells with higher endogenous circANRIL expression showed a stronger induction of apoptosis and a reduced proliferative capacity as well (Fig. 8g,h). In iPSC-derived macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 16) circANRIL overexpression also caused an accumulation of pre-rRNAs (Fig. 8i) and induced apoptosis (Fig. 8j), thereby confirming that circANRIL-associated induction of nucleolar stress also occurs in cells that are relevant in atherogenesis in vivo.

Figure 8. Translation of circANRIL molecular mechanisms in human primary cells and human cohorts.

(a) CircANRIL overexpression in primary human SMC using the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-encoding, bicistronic pBI-CMV2 vector (green; Fig. 2a) and immunofluorescent staining of PES1 (red). Quantification of nucleoli (b) and nucleolar size (c) in circANRIL-overexpressing (GFP+) SMC and circANRIL-negative (GFP−) cells. AU, arbitrary units. (d) Quantification of pre-rRNAs following circANRIL overexpression in SMC. (e) Apoptosis and (f) proliferation in SMC transfected with circANRIL. Quadruplicate measurements per condition. Correlation of endogenous circANRIL expression in human SMC with (g) apoptosis and (h) proliferation (n=5; quadruplicate measurements each). (i) Quantification of pre-rRNA following circANRIL overexpression in iPSC-derived macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 16). (j) Apoptosis in iPSC-derived macrophages transfected with circANRIL. LI, luminescence intensity. Quadruplicate measurements per condition. (k) Association of 32S rRNA expression with 9p21 A (n=49), H (n=114) and G (n=55) haplotypes in endarterectomy specimens. ***P<0.001. Two-tailed unpaired Student's t-tests were applied in b,e,f and j, and Mann–Whitney U-testing in k. Data are given mean±s.e.m.

Further in vivo evidence was obtained from human atherosclerotic plaques (n=218) (Fig. 8k). Here we observed significant correlations of circANRIL with 36S (rs=0.17, P=0.003, Mann–Whitney U-test) and 32S pre-rRNA abundance (rs=0.21, P=0.0003; Mann–Whitney U-test) but not with 47S pre-rRNA (rs=−0.01, P=not significant; Mann–Whitney U-test) or with 7SL control RNA abundance (rs=0.09, P=not significant; Mann–Whitney U-test). This indicates that high circANRIL levels led to an accumulation of pre-rRNA in human vascular tissue. In this cohort, 32S pre-rRNA was also elevated in patients carrying the CAD-protective allele at 9p21 (Fig. 8k), linking the atheroprotective genotype with high circANRIL expression (Fig. 1d–f) and pre-rRNA accumulation in vivo. To further translate our findings, we performed pathway analyses of genome-wide expression data, obtained from PBMC of 1,933 subjects of our cohort of patients with CAD20. While no transcripts were significantly associated with the 9p21 genotype at a genome-wide level17, gene set enrichment analyses of circANRIL-correlated genes (n=1,864; p≤0.001 (Ingenuity Pathway Analysis)) revealed induction of p53 signalling as the most significantly enriched pathway (Table 1) demonstrating that circANRIL also promoted nucleolar stress in vivo. Taken together, genome-wide expression and pathway analyses in large human CAD cohorts, pre-rRNA expression levels in human atherosclerotic plaques and functional studies in relevant human cells validate a circRNA effector mechanism, where circANRIL controls pre-rRNA maturation and nucleolar stress and thereby may act as protective factor against human atherosclerosis.

Table 1. Upstream regulator analysis of circANRIL-correlated transcripts in PBMC of the LIFE Heart Study (n=2,280).

| Transcription regulator | P-value |

|---|---|

| TP53 | 7.8 × 10−09 |

| E2F1 | 1.8 × 10−07 |

| STAT5A | 2.9 × 10−07 |

| IRF8 | 5.2 × 10−07 |

| STAT1 | 5.8 × 10−06 |

| SMARCA4 | 6.5 × 10−06 |

| ELF4 | 1.5 × 10−05 |

Transcripts correlated with circANRIL expression (P<0.001; n=1,864, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis) were included in the analysis.

Discussion

Our work provides a proof of concept for a long non-coding circRNA as a molecular regulator of rRNA maturation and of key cellular functions relevant to human disease. Results of this study extend our current knowledge about the molecular mechanisms of circRNAs, previously including the escape from translation8 and miRNA sponging2,9, to control of ribosomal RNA maturation through circRNA-protein interaction. We show that circANRIL binds to the C-terminal lysine-rich domain of PES1, thereby preventing pre-rRNA binding and exonuclease-mediated rRNA maturation25. Consequently, circANRIL impairs ribosome biogenesis, leading to activation of p53 and a subsequent increase in apoptosis and decrease in proliferative rate. Together, this pathway may promote atheroprotection by culling overproliferating cell types in atherosclerotic plaques.

PES1 is a nucleolar protein that is known to assemble in the PeBoW complex, which consists of PES1, BOP1 and WDR12. This complex is central for ribosome biogenesis and essential for life from yeast to mammals26,36. Additional support for an important role or the PeBoW complex in human atherosclerosis comes from genome-wide association studies of CAD, which independently identified WDR12 as an atherosclerosis modifier gene13,36,37. Human PES1 is a 588 amino-acid protein38, and previous work has shown that the central BRCT motif is essential for the incorporation of PES1 into the PeBoW complex and nucleolar localization30. In contrast, deletion of the C-terminal domain, containing NLS motifs, did not affect nucleolar localization but blocked rRNA maturation29. This was accompanied by changes in nucleolar morphology, inhibition of proliferation and induction of p53 in proliferating cells29. Results of the current work establish the C-terminal domain of PES1 as the binding site of both circANRIL and pre-rRNA. circANRIL binding prevented exonuclease-mediated processing of pre-rRNA, causing a dominant-negative phenotype as observed for the C-terminal deletion mutants of PES1 (Fig. 7g-j). It is remarkable that circANRIL can interfere with rRNA processing despite the relatively low abundance of detectable circANRIL RNA in the cell. On the basis of the published copy number of CDR1as in HEK-293 cells2 and our finding that circANRIL is 4–6 times higher expressed than CDR1as in these cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a), we estimate that the copies of circANRIL RNA per HEK cell will amount to 800–1,000. As a working model of circANRIL function, the stoichiometry of circANRIL copies relative to copies of PES1 protein might determine the efficacy of blocking PES1-dependent rRNA processing. Assuming a median abundance of 8,000 protein molecules per cell for an average protein in a typical tissue culture line39, a stoichiometry of circANRIL RNA:PES1 protein of 1:10 can be estimated. These data suggest that PES1 might be inactivated by circANRIL at a certain percentage even in native, non-overexpressing cells. One might speculate that thereby, circANRIL may impair PES1-mediated rRNA processing and ultimately impair protein translation rate and cell growth. We also base this hypothesis on a previously published study where a dominant-negative phenotype has been revealed for a C-terminal deletion mutant of PES1, such that mutant PES1 incorporated into the PeBoW complex inactivated the complex and blocked processing of the 32S pre-rRNA, leading to stabilization of p53 and to cell cycle arrest29. Notably, we also detected a mosaicism of circANRIL expression levels in primary SMC and macrophages in vascular tissues (Fig. 1), suggesting that circANRIL's roles in curbing atherogenesis may have to be investigated on a single-cell level to fully appreciate circANRIL function.

Despite the fact that we overexpressed circANRIL only threefold in HEK-293 cells, it is also evident that the physiologically occurring differences in circANRIL expression observed in our human studies were smaller than in the overexpressing cell lines. Consequently, they are likely to be accompanied by smaller biological effects as well. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that effects in overexpressing cell lines could be replicated in human primary cells with the same directions of effects (Fig. 8). Moreover, we identified the same molecular effector mechanisms of circANRIL in stably overexpressing cell lines and human cohorts, where high circANRIL led to the accumulation of pre-rRNA and p53 activation. Since atherosclerosis develops throughout life, it is plausible that subtle genotype-directed gene expression differences modulate the risk to develop symptomatic atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease at a higher age. Therefore, studies in overexpressing cell lines might be viewed as a time-lapse of the protective effects of circANRIL seen in individuals carrying the 9p21 atheroprotective genotype free of atherosclerosis (Figs 1 and 8).

Recently, substantial progress has been made in understanding the molecular mechanism of RNA circularization. It is thought that exonic circRNAs are generated by so called ‘back-splicing', enhanced by complementary base pairing of inverted repeats in the circRNA flanking introns1,5,6,19,40,41. Current work has also revealed a growing number of proteins affecting exon circularization41,42,43, and the proportion of circular versus linear transcripts may depend on the presence of specific intronic binding sites for these factors44. Even though the mechanism of ANRIL circularization has not been the scope of this work, it is likely that single-nucleotide polymorphisms contained in the 9p21 haplotype are responsible for differential circANRIL formation. Since low linANRIL and high circANRIL expression was associated with atheroprotection at 9p21, our results also underscore the importance of a balanced expression of linear and circular RNA transcripts. More generally, our results support a concept where circularization might be protective to escape linear RNA function, which has been associated with the onset and progression of diseases16,17,45.

Soon after the identification of the 9p21 locus by human genome-wide association studies12,13, a mouse model with a 70 kb deletion at chromosome 4 (Chr4Δ70kb/Δ70kb), representing the mouse orthologue of the human 9p21 risk haplotype, has been published46. While the deletion had no effect on atherosclerosis, in vitro studies revealed increased proliferation of isolated aortic SMC from Chr4Δ70kb/Δ70kb animals46. The direction of effects was comparable to our results of the knockdown of circANRIL, which increased proliferation as well. It is, however, unlikely that the effects observed in the Chr4Δ70kb/Δ70kb mouse model are related to ANRIL, because phylogenetic analyses revealed that ANRIL is absent in mice and fully developed only in certain primates, including humans18. In line with this, we detected no ANRIL expression in mouse tissue, and therefore, mouse models are not informative for the study of ANRIL. Instead, results of our study support a recent gain of function of primate-specific non-coding circRNA in controlling evolutionary conserved protein complexes. Several RNAs without evident protein-coding function were shown to co-localize with ribosomes47, suggesting that regulation of ribosome biogenesis by lncRNAs might be a broader phenomenon in humans than previously anticipated.

But how may circANRIL-mediated inhibition of rRNA processing be linked to atheroprotection? A major finding of the current study was that circANRIL induced ‘nucleolar stress' (Figs 6, 7) with subsequent stabilization of p53. Oncologists are now considering nucleolar stress strategically as a potential anticancer therapy32,48. In a similar fashion as cancer, atherosclerosis may be viewed as a proliferative disease. However, the role of proliferation and apoptosis in atherosclerosis is multi-facetted and inhibition of cellular proliferation and induction of apoptosis is not necessarily atheroprotective under all circumstances. For instance, while apoptosis in endothelial cells (EC) is proatherogenic, apoptosis in macrophages might attenuate early progression but can also induce secondary inflammation and plaque rupture49. The net effect of these individual mechanisms is difficult to determine experimentally. Nevertheless, one of our key observations was that p53 was induced on circANRIL overexpression, and mouse models have demonstrated that p53 is atheroprotective50,51, providing further evidence for an atheroprotective net effect of circANRIL.

Taken together, our data suggest circANRIL as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of atherosclerosis, since it might promote antiatherogenic cell functions and is particularly stable against degradation. High stability seems to be a common feature of circRNAs1,19, which might therefore serve as attractive novel therapeutic targets for human diseases in more general terms.

Methods

Study cohorts

Association analysis of gene expression was performed in samples of the LIFE Heart Study (n=2,280), a cross-sectional cohort study of patients undergoing coronary angiography for suspected CAD20. The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University Leipzig (Reg. No 276-2005). Human endarterectomy specimens (n=218) were collected in a cohort of patients undergoing vascular surgery, and the utilization of human vascular tissues was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty Carl Gustav Carus of the Technical University Dresden (EK316122008)17,52. Human primary cells (EC, SMC and adventitial fibroblasts (FB)) from non-diabetic, non-smoking patients and liver samples were obtained and experimental procedures were performed within the framework of the non-profit foundation Human Tissue and Cell Research53. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

DNA and RNA isolation and 9p21 genotyping

Isolation of DNA and RNA from PBMC, human primary tissues and cells was performed using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific)16,17. RNA from nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions and whole-cell lysates for RNA distribution studies were prepared using the PARIS Kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Chr9p21 protective (A) and risk (G) haplotypes (Fig. 1d,e) were defined by single nucleotide polymorphisms rs10757274, rs2383206, rs2383207 and rs10757278 (refs 16, 52).

Reverse transcription

RNA from human samples and cell lines was reverse transcribed using random hexamer primers (Roche). For validation of circular RNA overexpression, RNA was reverse transcribed with random hexamer primers (Roche Life Sciences), detecting linear and circular RNA transcripts and oligo(OdT) primers (Roche Life Sciences), for detecting linear transcripts containing poly-A tails. For miRNA quantification, RNA was reverse transcribed using the miScript II RT Kit (Qiagen).

PCR and qPCR

The AmpliTaq DNA Polymerase (Life Technologies) was used for PCR and qPCR reactions. PCR reactions for amplification of circANRIL were performed in cDNA from SMC, FB, EC, MonoMac and HEK-293 cells, with outward-facing primers in ANRIL exon 6 (ref. 14). No PCR products were amplified in EC. PCR products were cloned using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Life Technologies) and sequenced with an automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Quantification of gene expression was performed on a ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies) according to published protocols and normalized to plasmid standard curves17. PCR products were visualized using the Lonza FlashGel System (Biozym). Primers and probes for amplification of linANRIL (synonymous to ANRIL ex18-19 in ref. 17), U1, beta actin (BA), GAPDH, CDKN2A (p14ARF, p16INK4a), CDKN2B (p15INK4b)17, MALAT1 (ref. 54) and CDR1as (ref. 2) were used according to published protocols. Primers and probes for circANRIL (ex7-5), lin+circANRIL (ex6-7), circHPRT1 (ex6-2), lin+circHPRT1 (ex2-3), PES1, sex-determining region Y-box 2 (SOX2) and v-maf avian musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homologue (MAF)55 are given in the Supplementary Table 9. Expression of 47S, 36S and 32S rRNA and 7SL RNA control was determined according to ref. 31 using the KAPA SYBR FAST reagent (PeqLab). Quantification of miRNAs Hs_miR-3184-3p_1 (MS00041944, Qiagen), Hs_miR-4659b-3p_1 (MS00040390, Qiagen) and Hs_miR-5571-5p_1 (MS00038360, Qiagen) was performed with the miScript SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) and normalized to Hs_miR-27b_2 (MS00031668, Qiagen).

Genome-wide expression profiling

Illumina HumanHT-12 v4 BeadChips arrays were used for expression profiling in human PBMC (n=2,280) of the LIFE Heart Study and in cell lines with stable circANRIL overexpression (n=3) and vector control (n=3). For data from cell lines, bead-level data preprocessing was done in Illumina GenomeStudio followed by quantile normalization and background reduction according to standard procedures in the software. Preprocessing of expression data in PBMC of the LIFE Heart Study comprised selection of expressed features, outlier detection, normalization and batch correction17. Gene expression data have been deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE65392).

Expression vectors

CircANRIL, circANRIL-BoxB, BoxB and circHPRT1 sequences were synthesized (Eurofins Genomics) with adjacent 5′- and 3′-140 bp intronic sequences (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 1) and cloned in the bicistronic pBI-CMV2 (Clontech) vector allowing parallel expression of a green fluorescent protein and RNA transcripts. Stable cell lines were generated through co-transfection with a neomycin-encoding vector17. PES1 wild type (PES1-WT) and truncated PES1 (PES1Δ1–54 and PES1Δ446–588, respectively; Fig. 6f and Supplementary Table 8) were cloned in the pmCherry-N1 vector (Clontech) encoding a neomycin resistance and allowing overexpression of PES1 fused to a red fluorescent protein (RFP).

Cell culture and functional studies

HEK-293 (DMSZ, ACC305) were cultured in DMEM (Life Technologies) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Biochrom) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S; Life Technologies). MonoMac cells (DSMZ, ACC124) were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Biochrom) containing 10% FCS, 1% P/S, 1% MEM (Life Technologies) and 1% OPI (Sigma). Primary arterial SMC (n=5) and FB (n=5) were cultured in Smooth Muscle Cell Growth Medium 2 (PromoCell) and Fibroblast Growth Medium (PromoCell), respectively. iPSC were cultured using using mTeSR 1 Medium (STEMCELL Technologies)56 and differentiated into macrophages55. For generation of stably overexpressing cells, HEK-293 were transfected with ANRIL-pBI-CMV2 vectors (Clontech) and neomycin-encoding vector, cells were selected with geneticindisulfate (G418, Roth)17 and overexpression was validated using specific qPCRs. At least three cell lines were generated per isoform and vector control, respectively. Knockout of the 9p21 locus in HEK-293 cells was accomplished using CRISPR/Cas9 technology56 with guide RNAs (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 10) and controlled using PCR and sequencing (Fig. 3a,b; Supplementary Tables 2 and 10). Transient transfection of HEK-293 9p21 mutant, primary SMC and iPSC-derived macrophages was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) or Nucleofector technology (Lonza) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cellular proliferation was determined using CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega). Apoptosis was induced by staurosporine (0.25 and 0.5 μM; Calbiochem) and quantified by a caspase-3 activity assay (Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay; Promega). Measurements were performed on the SpectraMax Paradigm Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices). Transfection of siRNA was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) or Nucleofector technology (Lonza) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following siRNAs were used for downregulation of ANRIL isoforms: non-circANRIL: n272158, exon 1 (Life Technologies); circANRIL: 2046125, exon 7 (Qiagen); GAPDH (4390849; Life Technologies); and SCR control (Silencer Select Negative Control No. 1 siRNA, 4390843; Life Technologies). siRNA-mediated downregulation of ANRIL or overexpression of ANRIL and PES1 isoforms was validated by isoform-specific qPCRs and western blotting, respectively. All experiments were performed in quadruplicates using 2–4 biological replicates. To assess RNA stability, cells were incubated with actinomycin D (50 ng ml−1; Sigma) for up to 72 h. For pre-mRNA splicing inhibition, cells were incubated with isoginkgetin (Calbiochem) for 24 h.

Antibodies

Antibodies for western blotting, immunofluorescent staining and RIP, and secondary antibodies are given in Supplementary Table 11.

Western and northern blotting

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions and whole-cell lysates for western blotting were prepared using the PARIS Kit (Ambion) and run on NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels (Life Technologies). Primary and secondary peroxidase-labelled antibodies are given in Supplementary Table 11, AceGlow-Solution (PeqLab) was used for visualization of the chemiluminescent light signal of protein bands (white on black background) using the Fusion-FX7 Advance system (PeqLab). For northern blot analysis, 2 μg of total RNA isolated from HEK-293 cell lines with stable circANRIL or vector overexpression were separated on an 1% agarose gel containing formaldehyde and blotted onto a Hybond-N+ membrane (GE Healthcare). rRNA molecules were detected using the 3′-BITEG-labelled probes ITS1 and ITS2 (ref. 36) and streptavidin-POD (Roche). Western and northern blots were repeated three times and representative experiments are shown in the manuscript.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemical stainings

In situ RNA hybridization was conducted in formaldehyde-fixed endarterectomy tissues with digoxygenin (DIG)-labelled RNA probes (Roche Life Sciences) against circANRIL (exons 7–5–6; 381 bp) and sense negative control according to ref. 57. Anti-DIG-AP (Roche Life Sciences) was used as secondary antibody and staining was developed with NBT/BCIP solution (Roche Life Sciences). For dot blot analysis (Supplementary Fig. 12), RNA was spotted onto a Hybond-N+ membrane (GE Healthcare) and detected using a DIG-labelled probe against circANRIL and the anti-DIG-HRP antibody (PerkinElmer). Immunohistochemical staining of CD68 and SMA was performed using the ImmPRESS HRP Anti-Rabbit and Anti-Mouse Ig Polymere Detection System (Vector Laboratories) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine52. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemical stainings were performed three times and representative images are shown in the manuscript.

Immunofluorescent stainings

Cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100. After blocking with 5% goat normal serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), primary antibodies were applied overnight at 4 °C at a dilution 1:100. Secondary antibodies were applied at a dilution 1:500 for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma Aldrich) and samples were mounted with Fluorescence Mounting Medium (Dako). Pictures were taken with an Olympus Fluorescence Microscope OlympusBX40 and an Olympus XM10 camera. Immunoflurescent stainings were performed three times and representative images are shown in the manuscript. Nucleoli were counted per cell and nucleolar size was determined in px2 with the LAS V4.2 software (Leica).

λN-Peptide-mediated pull-down of circANRIL-bound proteins

Pull-down of circANRIL-BoxB (Supplementary Fig. 3; ref. 23) was performed with the N-terminal domain (amino acids 1–22) of the λN-peptide coupled to d-desthiobiotin (Intavis Peptide Services) according to ref. 58. As controls, cellular lysates from cell lines with stable overexpression of circANRIL were used. Streptavidin beads (Dynabeads MyOne, Life Technologies) were prewashed according to the manufacturer's instructions and blocked with 1 mg tRNA per ml and 1 mg BSA per ml in LN-buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1% NP40, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA and 1 mM dithiothreitol). Cellular lysates (1 mg total protein) were incubated with 100 μl streptavidin beads overnight at 4 °C in 1,000 μl LN-buffer, 100 μg tRNA per ml, 1 U RNasin per ml and 10% glycerine. After washing with 5 × with LN-buffer, 3 × with LN-buffer, 500 mM NaCl and 2 × with LN-buffer containing 250 mM LiCl instead of NaCl, circANRIL-BoxB-bound proteins were eluted with eluted with 100 μl Urea buffer (2 M urea and 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5)) supplemented with 1 mM dithiothreitol and 5 μg μl−1 trypsin and LysC. After alkylation with 5 mM iodoacetic acid (IAA), proteins were proteolytic digested with trypsin and LysC for 24 h. Peptides were acidified, loaded on SDB-RPS material and eluted and dried59. Peptides were resuspended in buffer A* (2% acetonitrile (ACN) and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)) and were briefly sonicated (Branson Ultrasonics, Ultrasonic Cleaner Model 2510) before mass spectrometric analyses. CircANRIL-BoxB RNA was eluted with 1% SDS, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 0.1 mM EDTA at 99 °C for 15 min, extracted with TRIzol (Life Technologies)/CHCl3 and precipitated with isopropanol. RNA was reverse transcribed with random hexamer primers and analysed by qPCR.

RNA immunoprecipitation

RIP was performed using antibodies given in Supplementary Table 11 (ref. 17). RFP-Trap_M (rtm-20, Chromotek) was used for immunoprecipitation of PES1-mCherry fusion proteins using incubation and washing buffers as for the λN-peptide-mediated pull-down. RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Life Technologies)/CHCl3 and precipitated with isopropanol. Retrieved RNA was reverse transcribed using random hexamer primers and analysed by qPCR with primers specific for circANRIL (ex7-5) or controls (CDR1as, circHPRT1).

PulseSILAC

CircANRIL-overexpressing and control cells were attenuated in ‘light' medium (Silantes) for three passages. After seeding and adhesion for 1 h, cells were switched to ‘medium' (SILAC-Lys4-Arg6-Kit, Silantes) and ‘heavy' medium (SILAC-Lys8-Arg10-Kit, Silantes) and incubated for 24 h (Fig. 4h). After washing with PBS, cell were lysed in SDC buffer (1% SDC, 10 mM TCEP, 40 mM CAA and 100 mM Tris (pH 8.5)), boiled for 10 min at 95 °C, sonicated and diluted 1:1 with ddH2O before proteolytic digestion. Peptide purification was done59 before mass spectrometric analyses.

Mass spectrometric data acquisition and data analyses

A unit of 2 μg of peptides from circANRIL-BoxB and circANRIL control pull-down experiments (n=4/4) were loaded for 30 min gradients separated on a 20 cm column with 75 μm inner diameter in-house packed with 1.9 μm C18 beads (Dr Maisch GmbH). A unit of 2 μg of peptides from pulseSILAC experiments were loaded for 100 min gradients separated on a 40 cm column with 75 μm inner diameter in-house packed with 1.9 μm C18 beads (Dr Maisch GmbH). Reverse phase chromatography was performed at 60 °C with an EASY-nLC 1,000 ultra-high pressure system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to the Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (for RNA pull-downs) or to the Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer (for pulseSILAC experiments) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) via a nanoelectrospray source (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were loaded in buffer A (0.1% (v/v) formic acid) and eluted with a nonlinear gradient. Operational parameters were real-time monitored by the SprayQC software60. Raw files were analysed by MaxQuant software (version 1.5.0.0 (RNA pull-downs) or version 1.5.0.38 (pulseSILAC experiments))61, and peak lists were searched against the Homo sapiens Uniprot FASTA database (Version 2014/4) and a common contaminants database (247 entries) by the Andromeda search engine62. Label-free quantification was done using the MaxLFQ algorithm63 integrated into MaxQuant. Data analysis was performed with the Perseus software in the MaxQuant computational platform and in the R statistical computing environment. Data were imputed by creating a Gaussian distribution of random numbers with a s.d. of 30% in comparison to the s.d. of measured values, and one s.d. downshift of the mean to simulate the distribution of low signal values.

miRNA-binding and RNA–protein interaction prediction

Predictions of miRNA-binding sites were performed using miRanda64 and TargetSpy65 algorithms. miRNA sequences were downloaded from miRBase (Release 21 (ref. 66)). The catRAPID67 and the RNA-Protein Interaction Prediction (RPISeq) software67,68 were used for predictions of protein–RNA binding. Secondary RNA structure prediction was performed using the Vienna RNA package69.

Pathway and upstream regulator analyses

Genome-wide expression profiling revealed 1,864 circANRIL-correlated transcripts in human PBMC (n=2,280; P<0.001) and 18,09 transcripts with >2- or <0.5-fold expression changes in circANRIL-overexpressing compared with vector control cells. Using pulseSILAC, 197 proteins with de novo synthesis ±10% in circANRIL-overexpressing compared with control cell lines were identified. Pathway and upstream regulator analyses were performed using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (www.ingenuity.com) according to standard procedures of the software. Levels of significance were determined using Fisher's exact tests implemented in the software. Bonferroni corrections for the number of tests were applied, and P values with genome-wide significance are given in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6.

Statistics

Normality of distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test implemented in the PRISM statistical software (GraphPad). Comparison of normally distributed multiple groups was done using analysis of variance and Tukey was performed as post-test. Comparison of two normally distributed groups was done using a t-test. Comparison of two non-normally distributed groups was done using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Mendelian randomization analysis and associations of haplotypes with gene expression and of circANRIL with atherosclerosis were calculated using the R software for statistical computing16,17,70.

Data availability

Gene expression data have been deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the GEO Accession number GSE65392. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/) with the data set identifier PXD001769. Original uncropped scans of DNA agarose gels and of western blots have been assembled in Supplementary Figs 17 and 18, respectively. All other data are available on request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Holdt, L. M. et al. Circular non-coding RNA ANRIL modulates ribosomal RNA maturation and atherosclerosis in humans. Nat. Commun. 7:12429 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12429 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1- 18 and Supplementary Tables 1-11

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Mock and F. Helfrich for technical support. This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of the CRC 1123 (Project B1) (L.M.H. and D.T.), the Leducq-foundation:CADgenomics (L.M.H. and D.T.) and by the LIFE project, which is funded by the European Union, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the Free State of Saxony within its initiative of excellence (L.M.H., K.K., M.S., F.B., J.T. and D.T.).

Footnotes

Author contributions Conceived and designed the experiments: L.M.H., K.S., G.P., N.A.K., K.K. and D.T.; performed the experiments: L.M.H., A.S., K.S., G.P., N.A.K., W.W., A.H., B.H.N., A.N. and K.K.; analysed the data: L.M.H., A.S., G.P., N.A.K., A.K. and B.H.N.; contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: L.M.H., G.G., F.B., M.S., J.T., K.M., M.M. and D.T.; wrote the paper: L.M.H., A.K. and D.T.

References

- Jeck W. R. et al. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA 19, 141–157 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memczak S. et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 495, 333–338 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzman J., Gawad C., Wang P. L., Lacayo N. & Brown P. O. Circular RNAs are the predominant transcript isoform from hundreds of human genes in diverse cell types. PLoS ONE 7, e30733 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro J. M. et al. Scrambled exons. Cell 64, 607–613 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubin R. A., Kazmi M. A. & Ostrer H. Inverted repeats are necessary for circularization of the mouse testis Sry transcript. Gene 167, 245–248 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. O. et al. Complementary sequence-mediated exon circularization. Cell 159, 134–147 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capel B. et al. Circular transcripts of the testis-determining gene Sry in adult mouse testis. Cell 73, 1019–1030 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeske Y. W., Bowles J., Greenfield A. & Koopman P. Expression of a linear Sry transcript in the mouse genital ridge. Nat. Genet. 10, 480–482 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen T. B. et al. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature 495, 384–388 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. U., Agarwal V., Guo H. & Bartel D. P. Expanded identification and characterization of mammalian circular RNAs. Genome Biol. 15, 409 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdt L. M. & Teupser D. From genotype to phenotype in human atherosclerosis—recent findings. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 24, 410–418 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani N. J. et al. Genome-wide association analysis of coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 443–453 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schunkert H. et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat. Genet. 43, 333–338 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd C. E. et al. Expression of linear and novel circular forms of an INK4/ARF-associated non-coding RNA correlates with atherosclerosis risk. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001233 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdt L. M. & Teupser D. Recent studies of the human chromosome 9p21 locus, which is associated with atherosclerosis in human populations. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 196–206 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdt L. M. et al. ANRIL expression is associated with atherosclerosis risk at chromosome 9p21. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 620–627 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdt L. M. et al. Alu elements in ANRIL non-coding RNA at chromosome 9p21 modulate atherogenic cell functions through trans-regulation of gene networks. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003588 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S., Gu W., Li Y. & Zhu H. ANRIL/CDKN2B-AS shows two-stage clade-specific evolution and becomes conserved after transposon insertions in simians. BMC Evol. Biol. 13, 247 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. & Wang Z. Efficient backsplicing produces translatable circular mRNAs. RNA 21, 172–179 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutner F. et al. Rationale and design of the Leipzig (LIFE) Heart Study: phenotyping and cardiovascular characteristics of patients with coronary artery disease. PLoS ONE 6, e29070 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotake Y. et al. Long non-coding RNA ANRIL is required for the PRC2 recruitment to and silencing of p15(INK4B) tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene 30, 1956–1962 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap K. L. et al. Molecular interplay of the noncoding RNA ANRIL and methylated histone H3 lysine 27 by polycomb CBX7 in transcriptional silencing of INK4a. Mol. Cell 38, 662–674 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gregorio E., Preiss T. & Hentze M. W. Translation driven by an eIF4G core domain in vivo. EMBO J. 18, 4865–4874 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milkereit P. et al. A Noc complex specifically involved in the formation and nuclear export of ribosomal 40 S subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4072–4081 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granneman S., Petfalski E. & Tollervey D. A cluster of ribosome synthesis factors regulate pre-rRNA folding and 5.8S rRNA maturation by the Rat1 exonuclease. EMBO J. 30, 4006–4019 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L., Sahasranaman A., Jakovljevic J., Schleifman E. & Woolford J. L. Jr Interactions among Ytm1, Erb1, and Nop7 required for assembly of the Nop7-subcomplex in yeast preribosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2844–2856 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N., Yanagida M., Fujiyama S., Hayano T. & Isobe T. Proteomic snapshot analyses of preribosomal ribonucleoprotein complexes formed at various stages of ribosome biogenesis in yeast and mammalian cells. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 22, 287–317 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson E., Ferreira-Cerca S. & Hurt E. Eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 126, 4815–4821 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm T. et al. Dominant-negative Pes1 mutants inhibit ribosomal RNA processing and cell proliferation via incorporation into the PeBoW-complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 3030–3043 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzel M. et al. The BRCT domain of mammalian Pes1 is crucial for nucleolar localization and rRNA processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 789–800 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrdlik A. et al. Nuclear myosin 1 is in complex with mature rRNA transcripts and associates with the nuclear pore basket. FASEB J. 24, 146–157 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James A., Wang Y., Raje H., Rosby R. & DiMario P. Nucleolar stress with and without p53. Nucleus 5, 402–426 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulon S., Westman B. J., Hutten S., Boisvert F. M. & Lamond A. I. The nucleolus under stress. Mol. Cell 40, 216–227 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger K. & Eick D. Functional ribosome biogenesis is a prerequisite for p53 destabilization: impact of chemotherapy on nucleolar functions and RNA metabolism. Biol. Chem. 394, 1133–1143 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castello A. et al. Insights into RNA biology from an atlas of mammalian mRNA-binding proteins. Cell 149, 1393–1406 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzel M. et al. Mammalian WDR12 is a novel member of the Pes1-Bop1 complex and is required for ribosome biogenesis and cell proliferation. J. Cell Biol. 170, 367–378 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathiresan S. et al. Genome-wide association of early-onset myocardial infarction with single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants. Nat. Genet. 41, 334–341 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita Y. et al. Pescadillo, a novel cell cycle regulatory protein abnormally expressed in malignant cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 6656–6665 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. J., Bickel P. J. & Biggin M. D. System wide analyses have underestimated protein abundances and the importance of transcription in mammals. PeerJ 2, e270 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov A. et al. Analysis of intron sequences reveals hallmarks of circular RNA biogenesis in animals. Cell Rep. 10, 170–177 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang D. & Wilusz J. E. Short intronic repeat sequences facilitate circular RNA production. Genes Dev. 28, 2233–2247 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwal-Fluss R. et al. circRNA biogenesis competes with pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 56, 55–66 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak-Wolf A. et al. Circular RNAs in the mammalian brain are highly abundant, conserved, and dynamically expressed. Mol. Cell 58, 870–885 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn S. J. et al. The RNA binding protein quaking regulates formation of circRNAs. Cell 160, 1125–1134 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Gesualdo F., Capaccioli S. & Lulli M. A pathophysiological view of the long non-coding RNA world. Oncotarget 5, 10976–10996 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visel A. et al. Targeted deletion of the 9p21 non-coding coronary artery disease risk interval in mice. Nature 464, 409–412 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heesch S. et al. Extensive localization of long noncoding RNAs to the cytosol and mono- and polyribosomal complexes. Genome Biol. 15, R6 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlatkovic N., Boyd M. T. & Rubbi C. P. Nucleolar control of p53: a cellular Achilles' heel and a target for cancer therapy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 771–791 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K. J. & Tabas I. Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell 145, 341–355 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara N. V., Kim H. S., Antonova E. I. & Chan L. The absence of p53 accelerates atherosclerosis by increasing cell proliferation in vivo. Nat. Med. 5, 335–339 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer J., Figg N., Stoneman V., Braganza D. & Bennett M. R. Endogenous p53 protects vascular smooth muscle cells from apoptosis and reduces atherosclerosis in ApoE knockout mice. Circ. Res. 96, 667–674 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdt L. M. et al. Expression of Chr9p21 genes CDKN2B (p15(INK4b)), CDKN2A (p16(INK4a), p14(ARF)) and MTAP in human atherosclerotic plaque. Atherosclerosis 214, 264–270 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thasler W. E. et al. Charitable state-controlled foundation human tissue and cell research: ethic and legal aspects in the supply of surgically removed human tissue for research in the academic and commercial sector in Germany. Cell Tissue Bank. 4, 49–56 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi V. et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 controls cell cycle progression by regulating the expression of oncogenic transcription factor B-MYB. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003368 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagimachi M. D. et al. Robust and highly-efficient differentiation of functional monocytic cells from human pluripotent stem cells under serum- and feeder cell-free conditions. PLoS ONE 8, e59243 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters D. T., Cowan C. A. & Musunuru K. Genome editing in human pluripotent stem cells. StemBook, ed. The Stem Cell Research Community (2013). [PubMed]

- Anderegg U., Saalbach A. & Haustein U. F. Chemokine release from activated human dermal microvascular endothelial cells—implications for the pathophysiology of scleroderma? Arch. Dermatol. Res. 292, 341–347 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch J. D. et al. Easily reversible desthiobiotin binding to streptavidin, avidin, and other biotin-binding proteins: uses for protein labeling, detection, and isolation. Anal. Biochem. 308, 343–357 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulak N. A., Pichler G., Paron I., Nagaraj N. & Mann M. Minimal, encapsulated proteomic-sample processing applied to copy-number estimation in eukaryotic cells. Nat. Methods 11, 319–324 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheltema R. A. & Mann M. SprayQc: a real-time LC-MS/MS quality monitoring system to maximize uptime using off the shelf components. J. Proteome Res. 11, 3458–3466 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. & Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. et al. Andromeda: a peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J. Proteome Res. 10, 1794–1805 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. et al. Accurate proteome-wide label-free quantification by delayed normalization and maximal peptide ratio extraction, termed MaxLFQ. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13, 2513–2526 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright A. J. et al. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 5, R1 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm M., Hackenberg M., Langenberger D. & Frishman D. TargetSpy: a supervised machine learning approach for microRNA target prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 292 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S., Grocock R. J., van Dongen S., Bateman A. & Enright A. J. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D140–D144 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellucci M., Agostini F., Masin M. & Tartaglia G. G. Predicting protein associations with long noncoding RNAs. Nat. Methods 8, 444–445 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muppirala U. K., Honavar V. G. & Dobbs D. Predicting RNA-protein interactions using only sequence information. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 489 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacker M., Fontana W., Stadler P. F. & Schuster P. Statistics of RNA melting kinetics. Eur. Biophys. J. 23, 29–38 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.orgR Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1- 18 and Supplementary Tables 1-11

Data Availability Statement

Gene expression data have been deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the GEO Accession number GSE65392. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/) with the data set identifier PXD001769. Original uncropped scans of DNA agarose gels and of western blots have been assembled in Supplementary Figs 17 and 18, respectively. All other data are available on request.