Abstract

Van der Waals heterostructures composed of two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenides layers have recently emerged as a new family of materials, with great potential for atomically thin opto-electronic and photovoltaic applications. It is puzzling, however, that the photocurrent is yielded so efficiently in these structures, despite the apparent momentum mismatch between the intralayer/interlayer excitons during the charge transfer, as well as the tightly bound nature of the excitons in 2D geometry. Using the energy-state-resolved ultrafast visible/infrared microspectroscopy, we herein obtain unambiguous experimental evidence of the charge transfer intermediate state with excess energy, during the transition from an intralayer exciton to an interlayer exciton at the interface of a WS2/MoS2 heterostructure, and free carriers moving across the interface much faster than recombining into the intralayer excitons. The observations therefore explain how the remarkable charge transfer rate and photocurrent generation are achieved even with the aforementioned momentum mismatch and excitonic localization in 2D heterostructures and devices.

Van der Waals heterostructures, fabricated via vertical stacking of two-dimensional materials, hold promise for opto-electronic applications. Here, the authors study the exciton-assisted charge transfer mechanisms occurring in a WS2/MoS2 heterojunction via ultrafast microspectroscopy.

Van der Waals heterostructures, fabricated via vertical stacking of two-dimensional materials, hold promise for opto-electronic applications. Here, the authors study the exciton-assisted charge transfer mechanisms occurring in a WS2/MoS2 heterojunction via ultrafast microspectroscopy.

Two-dimensional (2D) materials, including graphene, hexagonal boron nitride, layered transition-metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs), as well as black phosphorus, have demonstrated a wide variety of unique optical, electrical, thermal and mechanical properties1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Atomically thin opto-electronic devices produced by stacking layers of 2D materials9,10,11 to form Van der Waals (VDW) heterostructures have demonstrated fascinating effects, including high mobility, high carrier inhomogeneity12 and high on/off ratios in vertical tunnelling transistors13,14,15,16,17,18.

Heterostructures composed of TMDC monolayers are of particular interest for fabricating light-harvesting and photoelectron devices10,14,19. TMDCs are known as the direct bandgap semiconductors with remarkably strong light–matter interactions7,8,20,21,22,23. The efficient separation of photo-excited electrons/holes and generation of across-layer flow of carriers and photocurrent were observed in TMDC heterostructures24,25,26,27. The observations further corroborate the promising perspective of the heterostructures as atomically thin opto-electronic devices, at the same time, raise an intriguing question28: how can an electron–hole pair, created by light, in these heterostructures undergo an efficient and fast charge separation that leads to photocurrent, despite the momentum mismatch between the layers, as well as the tightly bound nature of excitons in the 2D geometry? The relative lattice orientations of the two TMDC monolayers in a heterostructure are rarely aligned in real or momentum spaces28. As a result, electrons transferring across the heterojunction are expected to be accompanied by a large momentum change, and therefore significantly retarded28. At the same time, due to the poor screening of Coulomb potential in the 2D geometry, the binding energy of intra/inter layer excitons are 1–2 orders of magnitude higher than that of a typical Mott–Wannier exciton. These tightly bound electron–hole pairs need to overcome a high Coulomb barrier that is much higher than the thermal energy to dissociate and contribute to the photocurrent.

Here, to unravel this fundamentally important puzzle, we carry out ultrafast visible/infrared (IR) microspectroscopy studies on the cross-layer charge transport dynamics in WS2/MoS2 heterostructure. Different from the visible detection light used in previous works19,27, the energy of mid-IR detection pulse is well below the excitonic bands, as well as the exciton-binding energies in TMDC monolayers28,29,30. The transient absorption signals are therefore not affected by the tightly bound excitons, but instead sensitive to the photo-excited free carriers, as well as the weakly bound electron/hole pairs. Both species absorb low-energy photons to generate intraband transitions31. Our study provides unambiguous experimental evidence showing that interlayer charge transfers are stepwise: the charge transfers result in an intermediate state of electron/hole pair with excess energy before the formation of tightly bound interlayer excitons. The excess energy of the intermediate state (denoted as hot exciton28) available allows the sampling of a broader range of momentum space than that determined by the conduction band minimum (CBM) and valence band maximum (VBM) of the stacked heterojunction. Momentum conservation can therefore be overcome. At the same time, the excess energy in the hot intermediates leads to lower-binding energy and a larger electron–hole distance than those of the interlayer excitons. As the result, the intermediates may easily dissociate and contribute to the photocurrent in the presence of the internal/external potentials before relaxing to the interlayer excitons. The results therefore reveal the mechanism how the momentum mismatch and excitonic localization in 2D heterostructures are overcome to reach fast and efficient charge transfers, and photocurrent generation.

Results

Charges can efficiently transfer between MoS2 and WS2

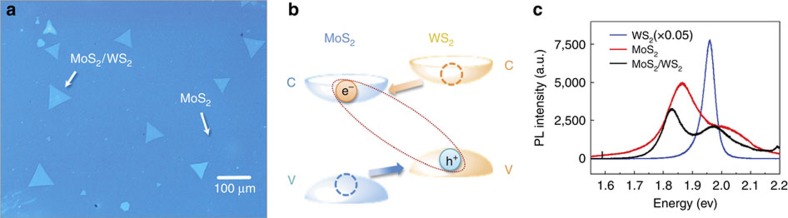

One optical image of the atomically thin MoS2/WS2 heterostructures is displayed in Fig. 1a. The bright triangles are the monolayer WS2 single crystals underneath a monolayer of MoS2 that covers the entire image. The samples were epitaxially grown via a two-step chemical vapour deposition method32. The well-defined WS2 triangular domains with ∼100 μm lateral size were firstly grown on SiO2/Si followed by a second time growth of overlaid MoS2 layers. The top MoS2 layers only have 0° and 60° relative orientations to the bottom WS2 layer corresponding to a AA and AB stacking, respectively. By controlling growth conditions, the top MoS2 domains coalesced into a continuous monolayer film as illustrated in Fig. 1a. Then, the as-grown WS2 single crystals and MoS2/WS2 VDW heterostructures were transferred onto CaF2 substrates for spectroscopic investigations. Raman spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy measurements (Supplementary Figs 1–3) confirm that each component of the hybrid is a monolayer.

Figure 1. Properties of the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure.

(a) Optical microscope image of an as-grown WS2/MoS2 heterostructure sample. Bright triangle areas correspond to WS2 single crystals covered with the MoS2 monolayer in the entire image. (b) Illustration of the band alignment of a MoS2/WS2 heterostructure. C, CBM; V, VBM. Optical excitation of the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure leads to tightly bound interlayer excitons, with electrons (e−) in MoS2 layer and holes (h+) in WS2 layer. (c) Photoluminescence (PL) spectra of as-grown WS2 monolayer, MoS2 monolayer and MoS2/WS2 heterostructure. The strong PL at 1.96 eV of the WS2 monolayer and at 1.86 eV of the MoS2 monolayer arise from their A-exciton resonances. Photoluminescences in the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure are quenched, compared with those in the standalone samples, indicating interlayer charge transfers in the heterostructure.

The band alignment of the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure is illustrated in Fig. 1b. The MoS2/WS2 heterostructure forms a type II heterojunction with the highest VBM and the lowest CBM residing in WS2 and MoS2 layers, respectively. The offset between two CBMs (VBMs) is 0.27 eV (0.35 eV)19,25. The optical excitation of the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure can lead to a tightly bound interlayer exciton with the electron (e−) in MoS2 and the hole (h+) in WS2 (refs 19, 25). The efficient charge transfer in the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure is confirmed by the photoluminescence (PL) measurements. Figure 1c displays the PL spectra of individual monolayer WS2, MoS2 and as-grown MoS2/WS2 heterostructure. The sharp peak at 1.96 eV of WS2 (blue) and the peak at 1.86 eV of MoS2 (red) arise from their A-exciton resonances. In the MoS2/WS2 heterojunction, the peak of MoS2 slightly red shifts, and that of WS2 slightly blue shifts, compared with the corresponding peaks of individual monolayers. The energy shifts are caused by the interlayer coupling. The coupling strength is calculated to be ∼0.05 eV. Calculation details are shown in Supplementary Note 1. The PL intensity of WS2 in the heterostructure is significantly reduced by >95% compared with that of the monolayer, indicating a very effective charge transfer in the heterojunction since a pair of spatially separated electron and hole in two TMDC layers cannot emit efficiently19,27.

Hot excitons form rapidly after the charge transfer

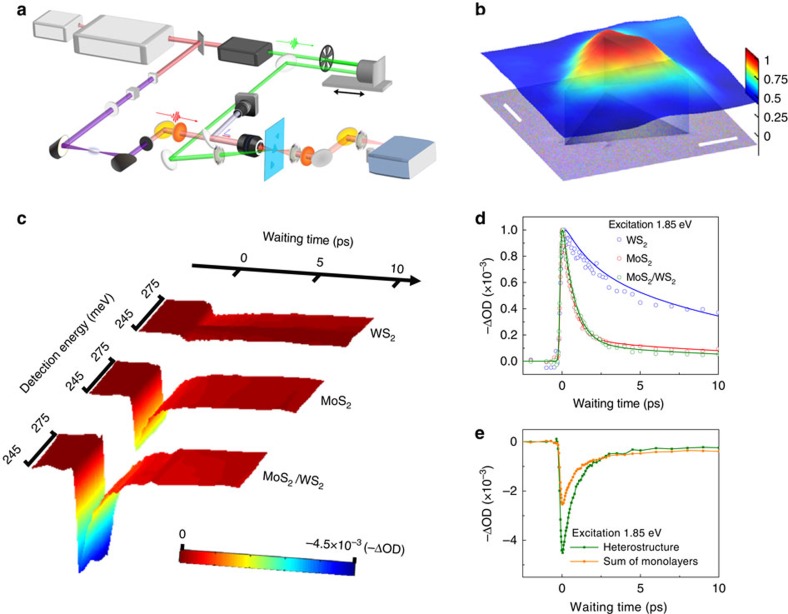

The real time charge transfer dynamics across the heterojunction were directly monitored with the ultrafast visible/IR microspectroscopy (Fig. 2a). In these experiments, a femtosecond energy-tunable visible pulse excites electrons in the sample from the valence band to the conduction band. The evolution of the photo-excited charge carriers is then monitored by recording the absorption change in the mid-IR region with a femtosecond ultra-broadband mid-IR pulse. In the studies, three sets of experiments were carried out, with the energy values of the visible excitation pulses centred at the A-exciton energy of MoS2 (1.85 eV), at the A-exciton energy of WS2 (1.95 eV) and at the free carrier energy (3.1 eV), respectively. Different carriers and charge transport dynamical processes were therefore generated in the heterostructure and monitored by the IR detection pulses, providing a comprehensive picture for the across-layer charge transfer dynamics.

Figure 2. Ultrafast visible/IR microspectroscopy measurements.

(a) A schematic illustration of ultrafast visible/IR microspectroscopy. (b) Image of transient absorption change for a 100 × 100 μm area of MoS2/WS2 heterostructure sample. The bottom layer of the figure is the optical image of the measured area, where the heterojunction is located at the centre. Scale bar, 20 μm. The top layer represents the transient absorption change 100 fs after the excitation of MoS2 with a pulse centred at 1.85 eV. The intensity of signal from the MoS2/WS2 heterojunction region is about twice of that from MoS2-only region. (c) Temporal evolutions of the 670 nm (1.85 eV) excitation-induced absorption changes detected at 0.245–0.275 eV of MoS2, WS2 and the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure. OD, optical density. (d) Normalized plots of (c) detected at 0.25 eV (2,000 cm−1). Dots are data, and curves are multi-exponential fitting with the consideration of instrument response function (IRF). (e) The signal of the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure and the signal sum of the two individual MoS2 and WS2 monolayers. The initial intensity of the heterostructure is nearly 100% larger than the signal sum of the two monolayers. All measurements were made at room temperature with incident pump fluence ∼80 μ J cm−2. The photo-excited carrier densities is ∼1012–1013 carriers per cm−2.

Figure 2b displays an image of transient absorption change for a MoS2/WS2 heterostructure sample. The top layer represents the transient absorption change 100 fs after the excitation of MoS2 with a pulse centred at 1.85 eV. The intensity of signal from the MoS2/WS2 heterojunction region is about twice of that from the MoS2-only region. The bottom layer of the figure is the optical image of the measured area, where the heterojunction is located at the centre.

Figure 2c (raw data) and Fig. 2d (normalized data) display the evolutions of the photo-excitation-induced absorption changes in MoS2 monolayer (red), WS2 monolayer (blue) and the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure (green) by exciting the samples with a pulse centred at 670 nm (1.85 eV) and detecting at ∼2,000 cm−1 (∼0.25 eV). Signals in all samples quickly reach maximum within fs time scales, and then decay in ps time scales. In the WS2 monolayer, the rising time is 120 fs, while in MoS2 and the heterostructure it is 50 fs. A marked enhancement of the signal maximum is observed (nearly 100% larger than the sum of the two standalone monolayers) in the heterostructure (Fig. 2c,e).

In the experiments, the optical excitation energy is centred at the A-exciton energy (1.85 eV) of MoS2 with a width ∼0.1 eV, lower than that (1.95 eV) of WS2 (refs 19, 25). In MoS2, therefore, electrons are excited to both excitonic band and conduction band because the sharp excitonic band absorption overlaps with the broad conduction band absorption33, forming both tightly bound excitons and other less tightly bound electron/hole pairs31. More detailed discussions about the carrier excitations are provided in Supplementary Fig. 6. The detection energy of ∼0.25 eV is well below the excitonic-binding energy (∼0.7 eV). Because of this, the excitons similar to a charge neutral-insulating gas34,35 can hardly absorb the detection IR photons. Consequently, the detection signal is predominantly contributed by the absorption of the weakly bound electron/hole pairs. The recombinations of these electron/hole pairs and their reorganizations to form excitons result in the signal decay. In WS2, on the other hand, electrons are excited to the tail of the conduction band (absorption spectrum is in literature33 and Supplementary Fig. 6), predominantly forming weakly bound electron/hole pairs, and very few A-excitons are generated. In the heterostructure, both MoS2 and WS2 are excited, and the signal is mainly contributed from the MoS2 excitation (Fig. 2c).

At the interface, charges of both intralayer excitons and weakly bound electron/hole pairs can transfer across the boundary26,27. Electrons move to MoS2 and holes transfer to WS2. The crossing-layer charge transfer is supported by the fast decay dynamics (∼0.8 ps) of the heterostructure that is essentially the same as that of MoS2, but apparently faster than that (∼2.0 ps) of WS2 (Fig. 2d, and also Fig. 3b,e), independent of the relative intensities of the two monolayers. (If charges did not transfer between two layers, the heterostructure decay dynamics would be the weighted average of the two monolayers). Absorption spectrum of MoS2 monolayers33 reveals that roughly half of the absorbed photons are converted to the energy of the intralayer excitons directly, with the rest going to the weakly bound electron/hole pairs. Detailed discussions of the carrier ratio estimation are in Supplementary Fig. 6. Before charge transfers, the intralayer excitons do not contribute to the detection signals because of their high-binding energy. After the transfer, the intralayer excitons become interlayer charge complexes. The binding energy of the charge complexes is smaller than the detection IR energy, and they absorb the detection IR phonons and enhance the signals, as observed in the experiments. Since the additional IR absorbers generated by the charge transfer of excitons are as many as those generated by the charge transfer of other carriers, the signal is almost doubled. This transfer mechanism is further supported by experiments displayed in Fig. 3d,e, where only free carriers are generated by photo excitation (3.10 eV) and the interlayer charge transfers only change the signal decay dynamics, but not the signal intensity. Detailed discussions will be provided later. Note that this signal enhancement observed might also be caused by the absorption change at the interface, as well as the interlayer coupling. However, the absorption of a heterostructure prepared by vertical heteroepitaxial growth is smaller than the sum of the two standalone monolayers due to interlayer interactions36,37. Therefore, the absorption change can be excluded as the reason. The increase of signal maximum cannot be caused by the interlayer coupling either, since no signal increase is observed at 3.10 eV excitation (Fig. 3d,f), which should be also affected by interlayer coupling. Multiple reflections between the two monolayers cannot cause the large intensity change either, because of the very small refractive index difference between MoS2 and WS2 that are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4.

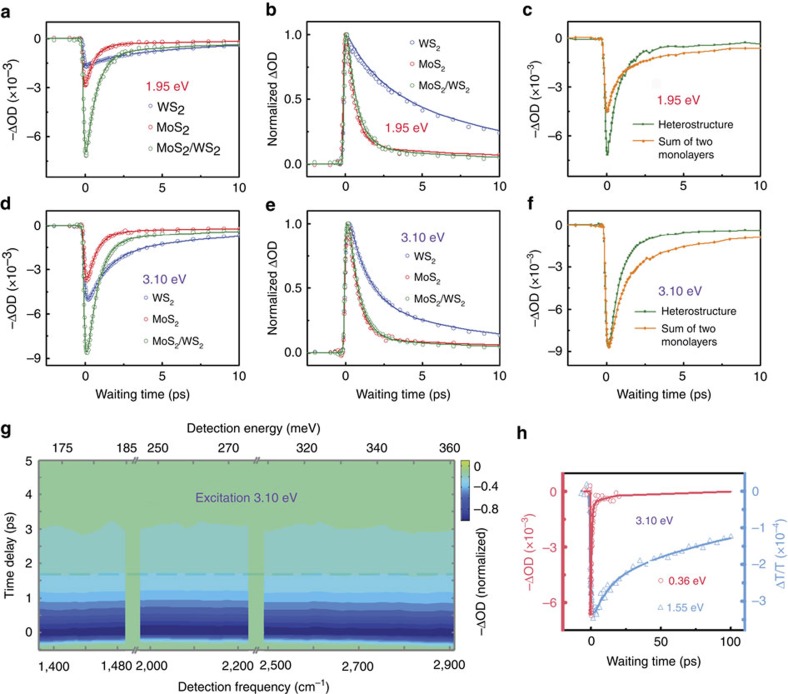

Figure 3. Dynamics following various photon excitations.

(a) Temporal evolutions of the 630 nm (1.95 eV, fluence 80 μ J cm−2) excitation-induced absorption changes detected at 2,000 cm−1(0.25 eV) of MoS2, WS2 and the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure. Dots are data, and curves are multi-exponential fitting with the consideration of IRF. (b) Normalized plots of a. (c) The signal of the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure and the simple signal sum of the two individual MoS2 and WS2 monolayers. (d) Temporal evolutions of the 400 nm (3.10 eV, fluence 10 μ J cm−2) excitation-induced absorption changes detected at 2,000 cm−1 (0.25 eV) of MoS2, WS2 and the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure. Dots are data, and curves are multi-exponential fitting with the consideration of IRF. (e) Normalized plots of d. (f) The signal of the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure and the simple signal sum of the two individual MoS2 and WS2 monolayers. (g) Temporal evolutions of the 400 nm excitation-induced absorption change at frequencies ranging from 1,390 (0.17 eV) to 2,910 cm−1 (0.36 eV) for the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure. The horizontal dashed line represents the time delay at which the signals decay to 20% of initial intensities. (h) Temporal evolutions of the 400 nm (3.10 eV) excitation-induced absorption changes detected at 2,910 cm−1 (0.36 eV, red) and 800 nm (1.55 eV, blue) of the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure. Dots are data, and curves are multi-exponential fitting with the consideration of IRF. 1.55 eV is larger than the binding energy of interlayer exciton and the slow signal decay indicates the long excitonic lifetime.

The interlayer charge transfer rate, derived from the signal rising edge of the heterostructures (Fig. 2c,d) is faster than 50 fs. The derivation is shown in Supplementary Note 2. Following the charge transfers, the signal decays very fast. The majority of the signal decays within 800±100 fs, and a small portion decays slower than 13±2 ps. The decays are significantly faster than those of the interlayer excitons detected with visible lights26,27 and near IR (tens to hundreds of ps; Fig. 3h). The fast decay dynamics, therefore, indicate that the charge transfers do not generate the tightly bound interlayer excitons directly. Instead, the interlayer charge separation immediately produces intermediate hot excitons with binding energy lower than the mid-IR detection energy ∼0.25 eV. The electrons of WS2 transfer to the conduction bands above CBM of MoS2 and the holes of MoS2 move to the valence bands below VBM of WS2. The majority of the hot excitons then dissipates the excess energy to the environment and forms the tightly bound interlayer excitons within 800 fs, and a small portion of the hot excitons recombines with 13 ps because of defects or phonon scattering.

The signal enhancement within 50 fs of the heterostructure (Figs 2e and 3c) and the decay dynamics of the heterostructure almost as fast as that of MoS2 (Figs 2d and 3b,e) indicate that the formation of interlayer hot excitons (faster than 50 fs) is significantly faster than the formation of intralayer excitons from free carriers or weakly bound charge complexes (600 fs–2.0 ps, Figs 2d and 3b,e).

The charges of excitons in WS2 transferring to MoS2 lead to a similar phenomena. In the second set of the experiments, the optical excitation energy was centred at 630 nm (1.95 eV). In WS2, both the A-excitons (1.95 eV) and weakly bound electron/hole pairs are generated. In MoS2, mainly the weakly bound electron/hole pairs are excited, and very few excitons (1.85 eV) are directly generated upon the optical excitation due to their relatively low energy. Similar to the results of experiments with 1.85 eV excitation, the maximum signal intensity of the heterostructure is apparently larger than the signal sum of the two standalone monolayers as displayed in Fig. 3a,c. As discussed above, the signal enhancement is also caused by the formation of interlayer hot exciton intermediates after the electron transfer of the A-excitons of WS2 to MoS2. The signal dynamics of the heterostructure are identical to those excited by the 1.85 eV photons, despite the relative signal intensity in each monolayer is different under the two excitations.

Formation of intralayer excitons is relatively slow

When free carriers are created and move across the heterojunction afterwards, no signal enhancement is observed. In the third set of experiments, the excitation pulse is tuned to 400 nm (3.10 eV). The photon energy is much higher than the bandgaps of MoS2 (2.39 eV) and WS2 (2.31 eV)19,25. Therefore, free carriers instead of excitons are generated38. In the standalone monolayer samples, the free carriers relax to form excitons, contributing to the fast signal decays16 (600±100 fs in MoS2 monolayer and 1.3±0.2 ps in WS2 monolayer) observed in Fig. 3d,e. The slow portion of the signal decays (∼10 ps) is attributed to the recombination of the free carriers through other ways, for example, the carrier-phonon scattering or defect assisted electron–hole recombination34. In the heterostructure, both MoS2 and WS2 are excited by the 3.10 eV light. More carriers are generated in the WS2 layer than in MoS2 (Fig. 3d). Similar to the observations with excitations at lower energy, the free carriers rapidly transfer across the interlayer boundary, resulting in a much faster signal decay of the heterostructure compared with that of WS2. The results clearly demonstrate that the interlayer charge transfers occur before the formation of intralayer excitons. After crossing the interlayer, the free carriers still remain free and able to absorb the mid-IR photons. The population of photo-induced free carriers is unchanged, and the absorption coefficients of carriers are almost unchanged because of the similar environment in MoS2 and WS2 monolayers, leading to that the interlayer charge transfers following the 3.10 eV excitation do not enhance the signal intensity (Fig. 3f). This is different from the observations with the excitation energy on resonance with the A-excitons (Figs 2e and 3c), where interlayer charge transfers of excitons produce extra mid-IR absorbers, as discussed above.

The observed fast signal decay in the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure is repeatable in different areas of the sample with different incident excitation fluences (from 5 to 20 μJcm−2). As the fluence increases, the excitation-induced absorption change increases with the same proportion and has not reached the nonlinear regime until the incident fluence reaches 20 μJcm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Under the excitation conditions, it is possible that biexcitons or other multi-particle species can be generated39. These multi-particle species can evolve into exciton pairs with excess energy in a fission-type process. However, the binding energy (∼50 meV)39 of these species is lower than the mid-IR-probe photon energy, and they contribute to the experimental signals in a way similar to free carriers that is not affected by interlayer charge transfer. Therefore, the generations of these multi-particle species do not affect the conclusion that the charge transfer of intralayer excitons results in interlayer hot excitons. More discussions about possible high-photoexcitation-density effects on the dynamics are provided in Supplementary Fig. 5. Figure 3g also demonstrates that the photo-induced dynamics in the heterostructure remain constant in the detection energy range from 1,390 (0.17 eV) to 2,910 cm−1 (0.36 eV), indicating that the binding energy of the interlayer hot exciton intermediate is <0.17 eV and that of the interlayer excitons is >0.36 eV.

In the above experiments, signals following the interlayer charge transfers decay significantly faster than that of the interlayer excitons observed with visible19 and near-IR detections (1.55 eV; Fig. 3h). As discussed above, experiments in this work detect free carriers and intermediate hot excitons with binding energy lower than the detection mid-IR photon energy. Charge complexes, for example, A-excitons, with higher binding energy do not contribute to the experimental signals. The binding energy of interlayer exciton in the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure has not been previously experimentally determined. Our experiments show that the 1.55 eV near-IR photon can excite the interlayer excitons (Fig. 3h), but the 0.36 eV mid-IR photon cannot (Fig. 3g), indicating that the binding energy of the interlayer excitons resides between 0.36 and 1.55 eV. Our calculations based on a model28 also suggest that the interlayer binding energy is 0.4–0.6 eV (Supplementary Fig. 7; Supplementary Note 3), slightly lower than that (0.5–0.7 eV) of a single layer28,29,30.

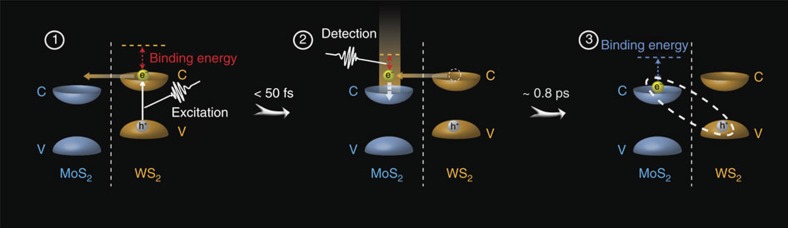

The charge transfers include two major steps

Our measurements herein suggest that the interlayer charge transfer process in the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure includes two major steps: the immediate formation of interlayer hot excitons following the ∼50 fs interlayer charge separation, and then the relaxation of hot excitons to generate tightly bound excitons within ∼800 fs. The process is schematically illustrated in Figs 4 and 5. The experimental observations support one of the two theories (the hot exciton theory) recently proposed28 to explain why the charge transfer dynamics in 2D heterostructures are little dependent on the momentum mismatch of intra- and inter-layer excitons: the momentum conservation during the charge transfer can be achieved by the formation of a hot interlayer exciton that employs the excess energy through the transfer. Specifically, after photo excitation, charge transfers don't form interlayer excitons directly. Instead, the electron (hole) transfers from WS2 (MoS2) to the conduction (valence) bands above (below) CBM (VBM) of the MoS2 (WS2), generating a hot interlayer exciton. The hot exciton has a relatively long distance between the electron and hole, and therefore is only weakly bound. The hot exciton then reorganizes and dissipates the excess energy to form the tightly bound interlayer exciton.

Figure 4. Charge separation processes in the heterostructure.

After the excitation of WS2 (MoS2) monolayer, the electron (hole) transfers from the CBM (VBM) of WS2 (MoS2) monolayer to the conduction (valence) bands just above (below) CBM (VBM) of the MoS2 (WS2) monolayer within 50 fs, generating a hot interlayer exciton with a relatively long distance. The hot exciton then reorganizes and dissipates the excess energy to form the tightly bound interlayer exciton within 800 fs.

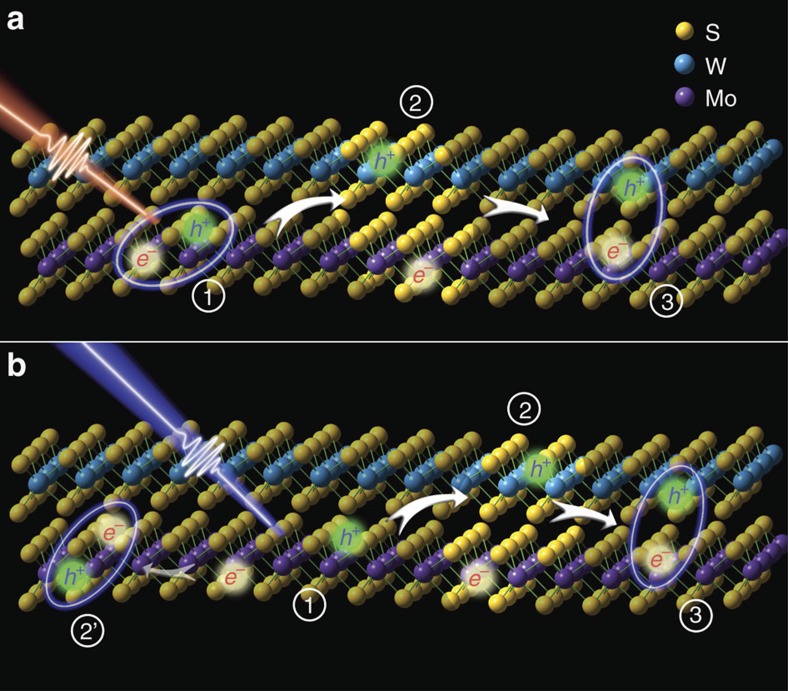

Figure 5. Illustration of the light-induced charge separation and the formation of interlayer exciton in a WS2/MoS2 heterostructure.

After photoexcitation, electron/hole pairs, (a) excitons and (b) other carriers, are generated in each individual layer (using MoS2 as an example), and then holes transfer to WS2 and electrons transfer to MoS2 to form the intermediate states—interlayer hot excitons, and the hot excitons finally relax to generate the tightly bound interlayer excitons. In b, the formation of interlayer intermediate is significantly faster than the formation of intralayer exciton .

Discussion

The experiments herein demonstrate that the ultrafast charge transfer between the WS2 and MoS2 monolayers results in the formation of interlayer hot excitons. The existence of hot excitons explain why the interlayer charge transfer is independent on the apparent momentum mismatch between the intralayer/interlayer excitons, and also answers why an electron–hole pair can overcome the large Coulomb potential to generate photocurrent in ultrathin photovoltaic cells with MoS2/WSe2 or MoS2/WS2 as the active p–n junction and conventional metal or graphene as contacting electrodes24,36. The excess energy of the hot interlayer exciton can help the electron/hole pair easily dissociate in the built-in potential before they turn into the tightly bound interlayer excitons28. That carriers other than excitons created in the heterostructure move across the interface with a much higher rate than recombining into the intralayer excitons also favours the generation of photocurrent. The semi-free character of the hot interlayer excitons can greatly facilitate the charge separation and photocurrent generation processes, which is critical for many applications of 2D heterostructures in optoelectronics and photovoltaics.

Methods

MoS2/WS2 heterostructures growth

Our heterostructure growth follows a two-step process: the WS2 domains were firstly grown on SiO2 substrates followed by second growth of MoS2 on the top of WS2. SiO2 substrate was pre-cleaned with acetone and isopropanol, followed by treated in piranha solution (H2SO4:H2O2—3:1) for 2 h. The triangular WS2 domains were firstly grown on SiO2 (300 nm)/p++Si substrates. Growth process was done in three-zone chemical vapour deposition system with 1-inch quartz tube using WO3 (Alfa Aesar 99.999%), MoO3 (Alfa Aesar 99.999%) and S (Alfa Aesar 99.9%) powders as the precursor. For MoS2 growth, typical temperatures for three zones are 115 °C, 560 °C and 800 °C, respectively. All of three temperature zones were heated to preset values at a rate of 25 °C min−1. Sulfur and MoO3 powders were separately loaded in two 10 mm-radius mini- quartz tubes, which enable a stable evaporation of S and MoO3 sources by preventing any cross-contaminations during the growth. All temperature zones were kept stable for 20 min before growth. The precursor powders were pre-placed right outside of the furnace and rapidly loaded from outside into each zone to start the growth. During the growth process, argon was used as a carrying gas at a flow rate of 130 sccm, and the vacuum pressure was kept at 0.7 torr.

Heterostructures transfer

The as-grown MoS2/WS2 VDW heterostructures are transferred onto CaF2 substrate for transmission mode laser experiments. The process is: at first, a thin layer of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA; PMMA-B4 4%wt) is spin-coated onto the sample on SiO2 substrate twice at the speed of 4,000 r.p.m., then the sample is carefully placed in the buffer HF (1:5) and let it float. After 20 h, the PMMA sheets is separated from the SiO2 substrate and fished with glass plate, move to deionized-water for rinsing a few times, then pre-cleaned CaF2 windows are used to fish the PMMA sheets. The CaF2 windows with PMMA and samples stay in room temperature and vacuum for 24 h, finally acetone is used to remove the PMMA, the MoS2/WS2 VDW heterostructures stayed on the CaF2 substrate and confirm by optical microscope.

Raman and PL measurements

Raman and PL spectroscopy were carried out using a Horiba Jobin Yvon LabRAM HR-Evolution Raman microscope. The excitation light is a 532 nm laser, with an estimated laser spot size of 1 μm and the laser power of 1 mW.

Ultrafast visible/IR microspectroscopy

The experimental set-up of the ultrafast visible/IF microspectroscopy is illustrated in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4. In brief, the output of a femtosecond amplifier laser system (at a repetition rate of 1 kHz, 1.6 mJ energy per pulse, 800 nm central wavelength and a pulse duration of ∼50 fs, Uptek Solutions Inc.) was split into two parts. One was used to pump a home-built nonlinear optical parametric amplifier to generate visible laser pulses with tunable wavelengths, and the other was directed to generate an ultra-broadband super-continuum pulse that covers almost the whole mid-IR region40,41. In ultrafast experiments, the visible pulse is the pump light with the central wavelength and excitation power adjusted based on need. The interaction spot on samples varies from 120 to 250 μm. The mid-IR super-continuum pulse acts as the probe light, which was focused at the sample by a reflective objective lens (× 15/0.28 numerical aperture, Edmund Optics Inc.) to reduce the spot size to the level of sample area (<40 μm). A 300-megapixel microscope digital camera was used to align the pump/probe beam to proper sample area. The probe light was detected by a liquid-nitrogen-cooled mercury–cadmium–telluride array detector after frequency resolved by a spectrograph with a resolution of 1–3 cm−1 that is dependent on the central frequency. The time delay between the pump light and probe light was controlled by a motorized delay stage.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Chen, H. et al. Ultrafast formation of interlayer hot excitons in atomically thin MoS2/WS2 heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 7:12512 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12512 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-7, Supplementary Notes 1-3, Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon the work supported by the AFOSR award no. FA9550-11-1-0070 and an AFOSR MURI, grant number FA9550-15-1-0022 ‘Shedding light on plasmon-based photochemical and photophysical processes' and the Welch foundation under award no. C-1752. J. R. Zheng also thanks the David and Lucile Packard Foundation for a Packard fellowship and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation for a Sloan fellowship, and the support of PKU. G. Y. Zhang thanks the funding supports from the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, grant nos 2013CB934500), the National Science Foundation of China (NSFC, grant nos 61325021) and Strategic Priority Research Program (B) of the Chinese Academy of sciences (grant no. XDB0710100). W. Zhuang thanks NSFC grant 21373201, NSFC Key grant 21433014, and the ‘Strategic Priority Research Program' of the Chinese Academy of Sciences XDB10040304 and XDB 100202002 for the financial support.

Footnotes

Author contributions J.Z. and H.C. designed the experiments. J.Z. supervised the project. H.C. and X.W. performed the ultrafast experiments. X.W., J.Z., Y.G., X.Z., J.Y., C.Y., J.L., P.A. and G.Z. prepared materials. T.W. and W.Z. performed the binding energy calculations. J.Z., H.C., W.Z. and G.Z., prepared and revised the manuscript.

References

- Novoselov K. et al. Two-dimensional gas of massless Dirac fermions in graphene. Nature 438, 197–200 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorenko A. N., Polini M. & Novoselov K. S. Graphene plasmonics. Nat. Photon. 6, 749–758 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Geim A. K. & Novoselov K. S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183–191 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., Liang T., Shi M. & Chen H. Graphene-like two-dimensional materials. Chem. Rev. 113, 3766–3798 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler S. Z. et al. Progress, challenges, and opportunities in two-dimensional materials beyond graphene. ACS Nano 7, 2898–2926 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J.-W. & Park H. S. Negative poisson's ratio in single-layer black phosphorus. Nat. Commun. 5, 4727 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhowalla M. et al. The chemistry of two-dimensional layered transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets. Nat. Chem. 5, 263–275 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh K., Kis A., Coleman J. N. & Strano M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699–712 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geim A. & Grigorieva I. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britnell L. et al. Strong light-matter interactions in heterostructures of atomically thin films. Science 340, 1311–1314 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponomarenko L. et al. Tunable metal-insulator transition in double-layer graphene heterostructures. Nat. Phys. 7, 958–961 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Dean C. et al. Boron nitride substrates for high-quality graphene electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 722–726 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou T. et al. Vertical field-effect transistor based on graphene-WS2 heterostructures for flexible and transparent electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 100–103 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W. J. et al. Highly efficient gate-tunable photocurrent generation in vertical heterostructures of layered materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 952–958 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy K. et al. Graphene-MoS2 hybrid structures for multifunctional photoresponsive memory devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 826–830 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J. et al. Electron transfer and coupling in graphene–tungsten disulfide van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 5, 5622 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. et al. High responsivity and gate tunable graphene-MoS2 hybrid phototransistor. Small 10, 2300–2306 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. et al. Ultrahigh-gain photodetectors based on atomically thin graphene-MoS2 heterostructures. Sci. Rep. 4, 3826 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong X. et al. Ultrafast charge transfer in atomically thin MoS2/WS2 heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 682–686 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radisavljevic B., Radenovic A., Brivio J., Giacometti V. & Kis A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak K. F., Lee C., Hone J., Shan J. & Heinz T. F. Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splendiani A. et al. Emerging photoluminescence in monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 10, 1271–1275 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Sanchez O., Lembke D., Kayci M., Radenovic A. & Kis A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 497–501 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.-H. et al. Atomically thin p–n junctions with van der Waals heterointerfaces. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 676–681 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong C. et al. Band alignment of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides: Application in tunnel field effect transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 053513 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Kang J., Tongay S., Zhou J., Li J. & Wu J. Band offsets and heterostructures of two-dimensional semiconductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 012111 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos F., Bellus M. Z., Chiu H.-Y. & Zhao H. Ultrafast Charge separation and indirect exciton formation in a MoS2–MoSe2 van der Waals heterostructure. ACS Nano 8, 12717–12724 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X.-Y. et al. Charge transfer excitons at van der Waals interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 8313–8320 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Wang H., Chan W., Manolatou C. & Rana F. Absorption of light by excitons and trions in monolayers of metal dichalcogenide MoS2: experiments and theory. Phys. Rev. B 89, 205436 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Berkelbach T. C., Hybertsen M. S. & Reichman D. R. Theory of neutral and charged excitons in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 88, 045318 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z. G., Krishnamurthy S. & Guha S. Photoexcited-carrier-induced refractive index change in small bandgap semiconductors. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 23, 2356–2360 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y. et al. Vertical and in-plane heterostructures from WS2/MoS2 monolayers. Nat. Mater. 13, 1135–1142 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigosi A. F., Hill H. M., Li Y., Chernikov A. & Heinz T. F. Probing interlayer interactions in transition metal dichalcogenide heterostructures by optical spectroscopy: MoS2/WS2 and MoSe2/WSe2. Nano Lett. 15, 5033–5038 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Zhang C. & Rana F. Ultrafast dynamics of defect-assisted electron–hole recombination in monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 15, 339–345 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaindl R. A., Carnahan M. A., Hägele D., Lövenich R. & Chemla D. S. Ultrafast terahertz probes of transient conducting and insulating phases in an electron–hole gas. Nature 423, 734–738 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi M., Palummo M. & Grossman J. C. Extraordinary sunlight absorption and one nanometer thick photovoltaics using two-dimensional monolayer materials. Nano Lett. 13, 3664–3670 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo H. et al. Interlayer orientation-dependent light absorption and emission in monolayer semiconductor stacks. Nat. Commun. 6, 7372 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubišić Čabo A. et al. observation of ultrafast free carrier dynamics in single layer mos2. Nano Lett. 15, 5883–5887 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You Y. et al. Observation of biexcitons in monolayer WSe2. Nat. Phys. 11, 477–481 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. et al. Molecular conformations of crystalline L-cysteine determined with vibrational cross angle measurements. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 15614–15624 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. et al. Vibrational cross-angles in condensed molecules: a structural tool. J. Phys. Chem. A 117, 8407–8415 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-7, Supplementary Notes 1-3, Supplementary References

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.