Abstract

Background

ATG1 belongs to the Uncoordinated-51-like kinase protein family. Members of this family are best characterized for roles in macroautophagy and neuronal development. Apoptosis-induced proliferation (AiP) is a caspase-directed and JNK-dependent process which is involved in tissue repair and regeneration after massive stress-induced apoptotic cell loss. Under certain conditions, AiP can cause tissue overgrowth with implications for cancer.

Results

Here, we show that Atg1 in Drosophila (dAtg1) has a previously unrecognized function for both regenerative and overgrowth-promoting AiP in eye and wing imaginal discs. dAtg1 acts genetically downstream of and is transcriptionally induced by JNK activity, and it is required for JNK-dependent production of mitogens such as Wingless for AiP. Interestingly, this function of dAtg1 in AiP is independent of its roles in autophagy and in neuronal development.

Conclusion

In addition to a role of dAtg1 in autophagy and neuronal development, we report a third function of dAtg1 for AiP.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12915-016-0293-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Apoptosis-induced proliferation, Atg1, ULK1/2, Autophagy, Jun-N-terminal kinase signaling

Background

Autophagy-related gene 1 (Atg1) in yeast, dAtg1 in Drosophila, uncoordinated-51 (unc-51) in C. elegans, and Unc-51-like kinase 1 and 2 (ULK1/2) in mammals are members of the evolutionary conserved Uncoordinated-51-like kinase (ULK) protein kinase family that play critical roles in macroautophagy (referred to as autophagy) and neuronal development (reviewed in [1, 2]). Autophagy is a catabolic process engaged under starvation and other stress conditions [3]. A critical step in autophagy is the formation of autophagosomes which trap cytosolic cargo for degradation after fusion with lysosomes [3]. Genetic studies in yeast identified Atg1 as an essential gene required for the initiation of autophagy [3–5]. This function of ULK proteins is conserved in evolution [6–9]. For this process, ATG1 forms a protein complex composed of ATG1/ULK1, ATG13, and ATG17 (FIP200), and in mammalian cells also ATG101 [10–15]. The ATG1/ULK complex phosphorylates several substrates including ATG9 [16, 17] and the Myosin light chain kinase (ZIP kinase in mammals, Sqa in Drosophila) [18], which are required for the formation of autophagosomes. Activation of the ATG1/ULK complex is also required for the recruitment of the ATG6/Beclin protein complex to the pre-autophagosomal structure (PAS) [3]. The ATG6/Beclin complex is composed of ATG6 (Beclin-1 in mammals), the type III PI3-K VPS34, as well as ATG14 and VPS15. Maturation of the PAS to autophagosomes requires lipidation of the ubiquitin-like ATG8/LC3 protein, which is mediated by two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems, ATG12 and ATG8/LC3 [3]. Critical components in these ubiquitin-like conjugation systems are ATG7 (E1), ATG10 and ATG3 (E2s), as well as another protein complex, ATG5-ATG12-ATG16, which serves as an E3 ligase for ATG8/LC3 lipidation [3, 19–21]. Finally, autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes for degradation of cargo.

In addition to a critical role in autophagy, ATG1 also has functions outside of autophagy, most notably in neuronal development. This was initially observed in mutants of the ULK ortholog unc-51 in C. elegans, which display uncoordinated movement with an underlying axonal defect [22–28]. A neuronal function of ULK orthologs was subsequently also reported in Drosophila, zebrafish and mammals [27, 29–33]. This autophagy-independent function of ULK proteins does not appear to involve other canonical autophagy proteins, including components of the ATG1/ULK protein complex such as ATG13 and FIP200 [34, 35]. Instead, the neuronal function of ULK proteins is dependent on different sets of proteins that include – depending on the organism analyzed – UNC-14, VAB-8 and PP2A (C. elegans), UNC-76 (Drosophila), and Syntenin and SynGAP (mammals) several of which are phosphorylated by ULKs [26–28, 33, 36–41]. Thus, the two known functions of ULK proteins in autophagy and neuronal processes involve different sets of proteins.

Apoptosis-induced proliferation (AiP) is a specialized form of compensatory proliferation that occurs after massive cell loss due to stress-induced apoptosis [42–45]. Initially described in Drosophila where it can compensate for the apoptotic loss of up to 60 % of imaginal disc cells [46], AiP has since been observed in many organisms, including classical regeneration models such as hydra, planarians, zebrafish, xenopus, and mouse [47–50]. Interestingly, AiP is directly dependent on a non-apoptotic function of caspases that otherwise execute the apoptotic program in the dying cell. In Drosophila, the initiator caspase Dronc triggers activation of Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling, which leads to the production of mitogens including Wingless (Wg), Decaplentaplegic (Dpp), and the EGF ligand Spitz for AiP [51–59].

However, many mechanistic details of AiP are still unknown. Therefore, we and others have developed several AiP models in eye and wing imaginal discs in Drosophila [52, 57, 58, 60–64]. In the first set of AiP models, apoptosis is induced upstream by expression of cell death-inducing factors such as hid or reaper, but blocked downstream by co-expression of the effector caspase inhibitor p35, generating ‘undead’ cells [52, 55, 56, 62]. Because undead cells do not die and P35 does not inhibit the initiator caspase Dronc, Dronc continues to generate the signals for AiP, which causes tissue overgrowth. For example, ey-Gal4-driven UAS-hid and UAS-p35 (ey > hid-p35) cause overgrowth of head capsules with ectopic sensory organs such as bristles and ocelli, and in severe cases forms amorphic head tissue (Fig. 1a–d) [52]. The ey > hid-p35 undead model is the only known overgrowth-promoting AiP model in which adult animals survive [52]. Other undead AiP models, mostly in the wing, such as nub > hid-p35 or hh > hid-p35 produce enlarged larval wing imaginal discs, but do not allow adult animals to eclose. Thus, the ey > hid-p35 undead AiP model is a convenient tool for genetic screening to identify genes involved in AiP by scoring adult flies.

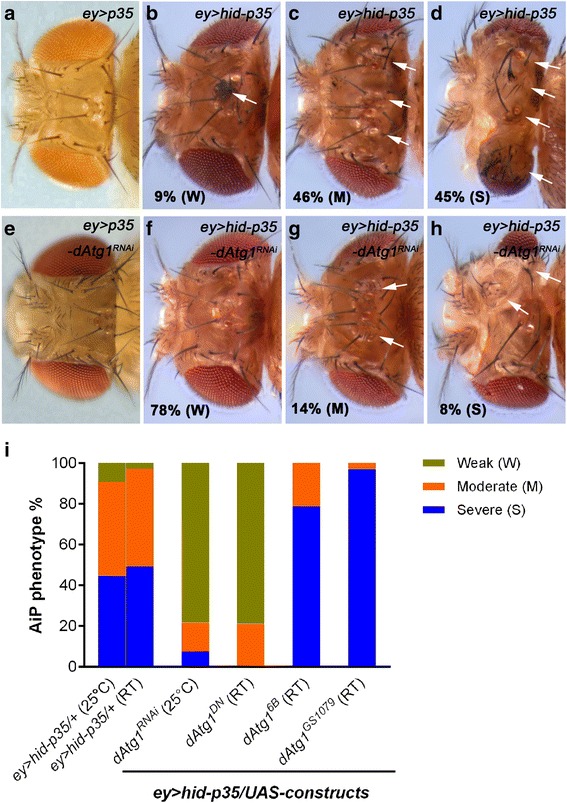

Fig. 1.

Suppression of ey > hid-p35 by loss of dAtg1. The hyperplastic overgrowth phenotype of ey > hid-p35 can be grouped in three categories, weak (W, including wildtype-like), moderate (M) and severe (S), as previously described [52]. Moderate flies are characterized by overgrowth of head capsules with duplications of bristles (arrows) and ocelli (arrowhead), while severe flies have overgrown and deformed heads with amorphic tissue. Each screen analysis was repeated at least twice with scoring more than 50 ey > hid-p35/(RNAi or mutant) adult flies. a–h Representative dorsal views of adult fly head capsules of the indicated genotypes. a–d Compared to the control ey > p35, which is similar to wildtype (a), percentages of ey > hid-p35 flies display weak (b), moderate (c) and severe (d) phenotypes (9 %, 46 %, and 45 %, respectively). Therefore, over 90 % of ey > hid-p35 flies show a clear hyperplastic overgrowth phenotype (either severe or moderate). e Knockdown of dAtg1 by RNAi in ey > p35 does not cause obvious defects on head capsules. f–h dAtg1 RNAi strongly reduces the percentage of ey > hid-p35 flies showing severe (8 %) and moderate (14 %) overgrowth phenotype and largely extends the population of flies with a weak or wildtype-like appearance (78 %). i Summary of the suppression of the ey > hid-p35 overgrowth phenotype by expressing dAtg1 RNAi or dominant-negative dAtg1 DN and the enhancement of the phenotype by expressing two constructs encoding dAtg1 (dAtg1 6B and dAtg1 GS1079). Either 25 °C or room temperature (RT, 22 °C) was used for these analyses. The majority of ey > hid-p35 flies (ey > hid-p35/+) display either severe or moderate overgrowth phenotypes at both 25 °C and RT. Blue indicates severe, orange indicates moderate, and green indicates weak or wildtype-like phenotypes

The second type of AiP models does not involve the use of p35 and has been referred to as genuine or regenerative AiP [43, 52, 60, 61, 63]. These models take advantage of Gal80ts, a temperature-sensitive inhibitor of Gal4, which allows temporal control of UAS-transgene expression by a temperature shift to 29 °C [65]. Because these AiP models are p35-independent, cells complete the apoptotic program and we score the ability of the affected tissue to regenerate the lost cells by new proliferation. In our genuine/regenerative AiP model, we express the pro-apoptotic factor hid for 12 h under control of dorsal-eye-Gal4 [66] (referred to as DEts-hid) in eye imaginal discs during second or early third larval instar [52]. This treatment causes massive tissue loss which is regenerated by AiP within 72 h after tissue loss.

Here, we report the identification of dAtg1 as a suppressor of the overgrowth phenotype of the undead ey > hid-p35 AiP model. dAtg1 is also required for complete regeneration in the DEts-hid AiP model. Furthermore, we show that dAtg1 is genetically acting downstream of JNK activation, but upstream of mitogen production such as Wg. Consistently, dAtg1 is transcriptionally induced by JNK activity during AiP. Interestingly, the involvement of dAtg1 in AiP is independent of other dAtg genes, including dAtg13, dAtg17/Fip200, dAtg6, vps15, vps34, dAtg7, and dAtg8. These findings suggest that dAtg1 has an autophagy-independent function in AiP. Finally, dAtg1 is not employing the mechanism used during neuronal development as targeting unc-76 did not affect AiP. Therefore, in addition to a role of dAtg1 in autophagy and neuronal development, we define a third function of dAtg1 for AiP.

Results

dAtg1 is a suppressor of apoptosis-induced proliferation

AiP phenotypes of ey > hid-p35 animals vary from mild to moderate to severe overgrowth of head capsules characterized by pattern duplications of ocelli, bristles, and sometimes entire antennae (moderate) as well as deformed heads with amorphic tissue (severe) (Fig. 1a–d) [52]. To identify genes required for AiP, we are screening for suppressors of the ey > hid-p35-induced overgrowth phenotypes. For follow-up characterization of identified suppressors, we are using undead and regenerative (p35-independent) AiP models in eye and wing imaginal discs.

Using this approach, we identified dAtg1 as a strong AiP suppressor of ey > hid-p35 by RNAi (Fig. 1f–h). The percentage of ey > hid-p35 animals with severe and moderate AiP phenotypes is strongly reduced upon dAtg1 knock-down (Fig. 1f–h; quantified in Fig. 1i). No effect was scored on control (ey > p35) animals (Fig. 1e). Although dAtg1 RNAi results in significant loss of dATG1 mRNA and protein levels (Additional file 1: Figure S1A–B’) and no off-targets have been reported, we tested additional reagents for an involvement of dAtg1 in AiP. Expression of a dominant negative dAtg1 transgene also suppressed ey > hid-p35-induced overgrowth (Fig. 1i). Furthermore, increased expression of dAtg1, which does not alter apoptosis (Additional file 2: Figure S2), enhances the AiP phenotype and generates many animals with severe AiP phenotype (Fig. 1i). We therefore conclude that dAtg1 is required for tissue overgrowth in the undead AiP model.

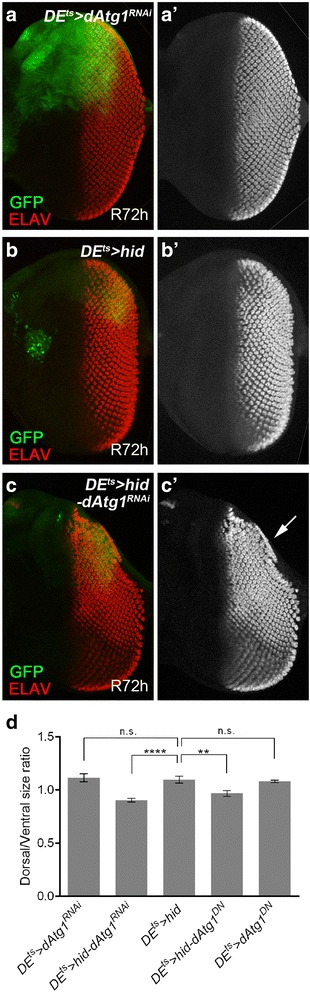

dATG1 is required for regenerative apoptosis-induced proliferation

Encouraged by the identification of dAtg1 in the undead AiP model, we examined an involvement of dAtg1 in the regenerative (p35-independent) DEts > hid AiP model. When hid expression is induced for 12 h in the dorsal half of the eye imaginal disc, the dorsal half of the eye disc is severely ablated [52]. After 72 h recovery (R72h), the disc has recovered due to regenerative growth by AiP (Fig. 2b) [52]. The degree of the regenerative response can be easily assessed by visualization of the photoreceptor pattern using ELAV as a marker, because photoreceptor differentiation follows tissue growth of the disc [67]. DEts > hid control discs regenerate a normal ELAV pattern 72 h after hid-induced tissue ablation (Fig. 2b, b’). In contrast, DEts > hid imaginal discs expressing dAtg1RNAi are unable to fully regenerate the ablated tissue (Fig. 2c). The ELAV pattern in the dorsal half of the eye disc is incomplete (arrow in Fig. 2c’), suggesting that the regenerative response after hid-induced tissue ablation is partially blocked by dAtg1 RNAi. As additional control, DEts > dAtg1RNAi alone does not affect the ELAV pattern (Fig. 2a, a’). These findings are also confirmed by expression of a dominant negative dAtg1 transgene and quantified in Fig. 2d. In summary, these data illustrate that dAtg1 is an important gene required for AiP in both undead and regenerative models. We also considered examining the effect of overexpressed dAtg1 in regenerative AiP. However, expression of dAtg1 alone using the DE-Gal4 driver triggers strong apoptosis (Additional file 2: Figure S2C), consistent with a previous report [6], which may complicate the interpretation of the results. Therefore, we did not characterize the role of overexpressed dAtg1 in the regenerative AiP model.

Fig. 2.

dAtg1 is required for complete tissue regeneration in response to apoptosis. a–c’ Late third instar eye discs, anterior is to the left. ELAV labels photoreceptor neurons and is used to outline the shape of the posterior part of the discs. Conditional expression of dAtg1 RNAi (a, a’), hid (b, b’), or hid and dAtg1 RNAi (c, c’) was under control of DE-Gal4 and tub-Gal80 ts (DE ts) and indicated by GFP. A temperature shift to 29 °C for 12 h during second instar larval stage induced expression of these transgenes which is followed by a recovery period of 72 h at 18 °C (R72h). (a, a’) Following such a temperature shift procedure, expression of dAtg1 RNAi alone (DE ts > dAtg1 RNAi) does not affect the eye disc morphology indicated by the normal ELAV pattern in the dorsal half of the eye disc (red in a, grey in a’). (b, b’) DE ts > hid induced massive apoptosis (GFP puncta and aggregates, arrow in b), which results in loss of bilateral symmetry of the disc 24 h after the temperature shift [52]. However, as indicated by the largely normal ELAV pattern in late third instar eye discs, the apoptosis-induced tissue damage has fully recovered after 72 h recovery (R72h) at 18 °C. (c, c’) A DE ts > hid eye disc that was simultaneously treated with dAtg1 RNAi (DE ts > hid-dAtg1 RNAi). The arrow in (c’) highlights the incomplete ELAV pattern on the dorsal half of the disc indicating that the regenerative response was partially impaired by reduction of dAtg1; 79 % (n = 28) of DE ts > hid-dAtg1 RNAi eye discs showed incomplete regeneration. (d) Quantification of the dorsal/ventral size ratio (mean ± SE) in eye discs of various genotypes. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison test was used to compute P values. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant change on dorsal/ventral size ratio compared to the control DE ts > hid. Compared to DE ts > hid, expression of dAtg1 RNAi or dAtg1 DN significantly (****P < 0.0001 and **P < 0.01, respectively) reduces the size of the dorsal half of the eye disc. As the controls, disc sizes of DE ts > dAtg1 RNAi and DE ts > dAtg1 DN are not significantly (n.s.) different from those of DE ts > hid

dAtg1 is required for AiP downstream of Dronc in undead eye and wing imaginal discs

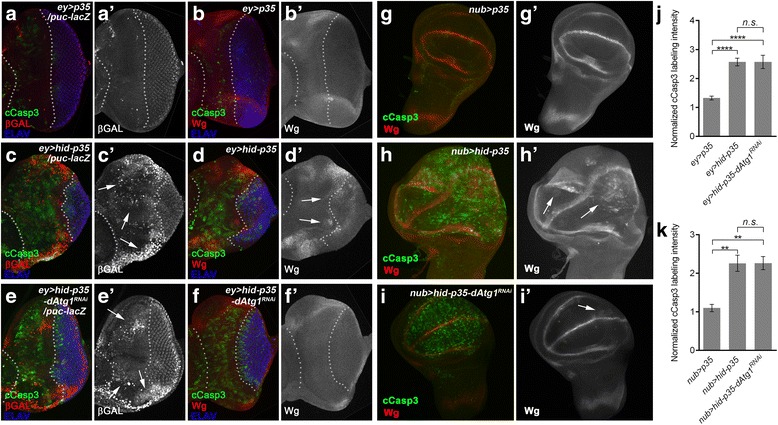

We further characterized the role of dAtg1 for AiP with molecular markers. Although dAtg1 is best characterized for a role in autophagy, it is theoretically possible that dAtg1 RNAi inhibits apoptosis and thus AiP indirectly. Therefore, we first tested how dAtg1 relates genetically to Dronc in the AiP pathway. As a marker for Dronc activity, we used the cleaved Caspase-3 (cCasp3) antibody. Although apoptosis is blocked by p35 expression, the cCasp3 antibody still labels undead cells (Fig. 3c, d), presumably because Dronc also has non-apoptotic substrates [52, 68]. dAtg1 RNAi suppresses the overgrowth and normalizes the morphology of the ey > hid-p35 eye disc as judged by ELAV labeling (Fig. 3e, f). However, cCasp3 labeling is not significantly altered by dAtg1 RNAi (Fig. 3e, f, j) despite the rescue of disc morphology suggesting that the loss of dAtg1 does not affect caspase activity in undead tissues.

Fig. 3.

dAtg1 acts genetically downstream of or in parallel to JNK and upstream of Wg expression. Late third instar eye (a–f’) or wing (g–i’) discs, anterior is to the left. The cleaved Caspase-3 (cCasp3) labeling (green in a–i) indicates activity of Dronc in p35-expressing tissues. White dotted lines in (a–f’) indicate the anterior portion of the eye discs which expresses ey-Gal4. ELAV labels photoreceptor neurons (blue in a–f) and is used to mark the posterior differentiating eye field. (a–b’) In ey > p35 control discs, puc-lacZ expression (β-Gal; red in a, grey in a’) as a marker of JNK/Bsk activity is low (a’, arrow) in the anterior portion of the eye discs. Expression of Wg (red in b, grey in b’) is restricted to dorsal and ventral edges of the eye discs. Dronc activity indicated by cCasp3 labeling is low. (c–d’) In ey > hid-p35 discs, Dronc activity (cCasp3 labeling) is strongly induced in undead anterior tissue (c, d). The anterior portion of the discs between the white dotted lines is significantly expanded and displaces the eye field in the posterior portion of the discs (ELAV). Compared to the ey > p35 control discs (a’, b’), in the overgrown anterior eye portion, JNK activity (c’, arrows) and expression of Wg (d’, arrows) are strongly induced. (e–f’) Expression of dAtg1 RNAi suppresses hyperplastic overgrowth in about 80 % of the ey > hid-p35-dAtg1 RNAi discs (n > 60) indicated by the normalized ELAV pattern. This ratio corresponds to the suppression of the adult overgrowth phenotype (Fig. 1i). However, puc-lacZ expression and cCasp3 labeling are not suppressed by dAtg1 RNAi (e’, arrows) in contrast to ectopic Wg expression, which is blocked (f’) in the anterior portion of the eye discs. (g–i’) Compared to the control wing discs where p35 is expressed in the pouch area under the control of nub-Gal4 (nub > p35; g, g’), in nub > hid-p35 discs, co-expression of hid and p35 induces tissue overgrowth, increased cCasp3 labeling, and ectopic Wg expression (h, h’; arrows). Similar to eye discs, expression of dAtg1 RNAi largely blocks tissue overgrowth and ectopic Wg, but not the cCasp3 labeling (i, i’). A low level of ectopic Wg remains in nub > hid-p35-dAtg1 RNAi discs (i’, arrow). (j, k) Quantification of cCasp3 labeling intensity in eye and wing discs (mean ± SE). dAtg1 RNAi has no obvious effects on the cCasp3 labeling induced by expression of hid and p35 in both eye (j) and wing (k) discs

We also characterized the involvement of dAtg1 in AiP in undead wing imaginal discs. Expression of hid and p35 under nub-Gal4 control (nub > hid-p35) causes strong overgrowth of the wing imaginal disc compared to nub > p35 control discs (Fig. 3g, h). dAtg1 RNAi suppresses the overgrowth of nub > hid-p35 wing discs, but leaves cCasp3 activity intact (Fig. 3i, k). To further confirm these data obtained by RNAi, we conducted mosaic analysis using dAtg1 null mutants in wing imaginal discs because homozygous dAtg1 mutants are early larval lethal in the ey > hid-p35 genetic background. Consistent with RNAi results, dAtg1 mutants do not alter cCasp3 labeling induced by co-expression of hid and p35 in MARCM clones (Additional file 3: Figure S3A–C). Similarly, dAtg1 mutant clones or RNAi do not suppress GMR-hid-induced apoptosis in the eye (Additional file 3: Figure S3D–F). Together, these data further confirm that loss of dAtg1 does not affect apoptosis and that dAtg1 controls AiP downstream of caspase (Dronc) activation.

dAtg1 is required for AiP downstream of JNK, but upstream of wingless in undead eye and wing imaginal discs

Next, because JNK is an important mediator of AiP [43, 52, 56, 57], we determined the position of dAtg1 relative to JNK in the AiP pathway. The JNK activity reporter puc-lacZ is strongly induced in AiP models compared to controls (Fig. 3a’, c’; arrows) [52, 54, 56, 57]. The morphology of the discs is severely disrupted, which correlates with signal intensity of puc-lacZ, especially in overgrown areas. In response to dAtg1 RNAi, overgrowth and disc morphology, as judged by ELAV labeling, is restored to almost normal (Fig. 3e). Nevertheless, despite the rescue of disc morphology, puc-lacZ expression is not significantly reduced (Fig. 3e’; arrows). These data suggest that dAtg1 acts downstream of or in parallel to JNK activity in the AiP pathway.

Finally, we determined the position of dAtg1 relative to wingless (wg), another marker in the AiP pathway [54–56]. Wg and its orthologs are critical mediators of AiP in regenerative responses in many animals (reviewed by [43, 45]). In undead eye discs, inappropriate wg expression is induced compared to controls (Fig. 3b, b’, d, d’; arrows). dAtg1 knockdown normalizes wg expression in the disc (Fig. 3f, f’). In addition, in undead nub > hid-p35 wing imaginal discs, wg expression is strongly induced (arrows in Fig. 3h’). However, similar to undead eye discs, co-expression of dAtg1 RNAi in nub > hid-p35 discs suppresses overgrowth (Fig. 3i) and normalizes the wg pattern (Fig. 3i’). Together, these analyses suggest that dAtg1 acts genetically downstream of Dronc and either downstream of or in parallel to JNK, but upstream of Wg, in the AiP network.

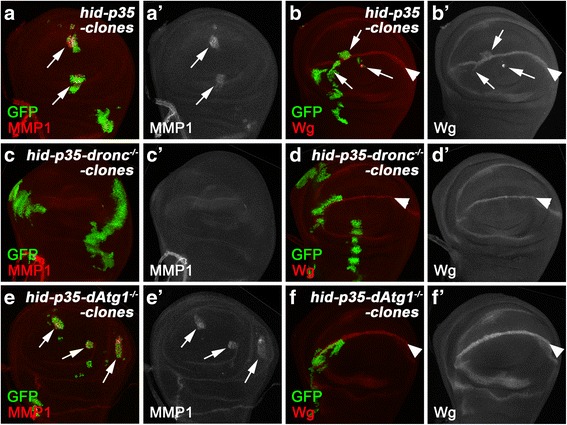

In addition to the RNAi analysis, we also co-expressed hid and p35 in either wildtype, dronc, or dAtg1 mutant clones (by MARCM) and examined for JNK activity (using MMP1 as JNK marker [69]) and Wg expression (Fig. 4a, a’, b, b’). Ectopic Wg expression is most frequently observed in the wing pouch area in close proximity to the dorsoventral boundary in the wing disc (Fig. 4b; arrows), similar to previous reports [56]. The induction of MMP1 and Wg expression is dependent on Dronc as co-expression of hid and p35 in dronc mutant clones suppresses these AiP markers (Fig. 4c–d’). Importantly, when hid and p35 were co-expressed in dAtg1 mutant clones, the expression of Wg was suppressed, while MMP1 expression was not affected (Fig. 4e–f’) suggesting that dAtg1 acts downstream of or in parallel to JNK activity, but upstream of Wg. These data are consistent with the RNAi data (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

dAtg1 is required cell autonomously for Wg expression, but not JNK activation, in undead clones. Late third instar wing discs with mosaic clones positively marked by GFP, anterior is to the left. MMP1 labeling (red in a, c, e and grey in a’, c’, e’) is used as marker of JNK activity. Wg (red in b, d, f and grey in b’, d’, f’) is highly expressed at the dorsal/ventral (D/V) boundaries (arrowheads in b, d, f) of wing discs. (a–b’) Simultaneous expression of hid and p35 in clones. MMP1 expression (arrows in a, a’) is induced in all hid and p35 co-expressing clones. Ectopic expression of Wg (arrows in b, b’) was observed in over 80 % of clones (n = 66) generated in close proximity to the D/V boundaries in the wing discs. Genotype: hs-FLP tub-GAL4 UAS-GFP/UAS-hid; UAS-p35/+; tub-GAL80 FRT80B/FRT80B. (c–d’) Simultaneous expression of hid and p35 in dronc mutant clones. Both MMP1 labeling and ectopic Wg expression, induced by co-expression of hid and p35, are completed blocked in dronc mutant clones (n > 30). Genotype: hs-FLP tub-GAL4 UAS-GFP/UAS-hid; UAS-p35/+; tub-GAL80 FRT80B/droncI29 FRT80B. (e–f’) Simultaneous expression of hid and p35 in dAtg1 mutant clones. hid and p35-induced MMP1 expression persists in dAtg1 mutant clones (arrows in e, e’). In contrast, the ectopic Wg expression induced by hid and p35 is suppressed in over 70 % of dAtg1 clones (n = 73) generated in close proximity to the D/V boundaries in the wing discs. Genotype: hs-FLP tub-GAL4 UAS-GFP/UAS-hid; UAS-p35/+; tub-GAL80 FRT80B/dAtg1 Δ3D FRT80B

Because dAtg1 is required for wg expression in AiP, we tested if dAtg1 was also sufficient for expression of AiP markers including wg, dpp, and kekkon1 (kek), the latter being a marker of EGFR activity [51, 52, 54–56, 70]. However, while expression of hid in the DEts > hid model is sufficient to induce wg, dpp, and kek expression (Additional file 4: Figure S4A–B’, D–E’, G–H’), expression of dAtg1 alone under the same conditions (DEts > Atg1) is not (Additional file 4: Figure S4C, C’, F, F’, I, I’). These observations suggest that, in addition to dAtg1 expression, additional caspase-dependent events have to occur in order to induce AiP.

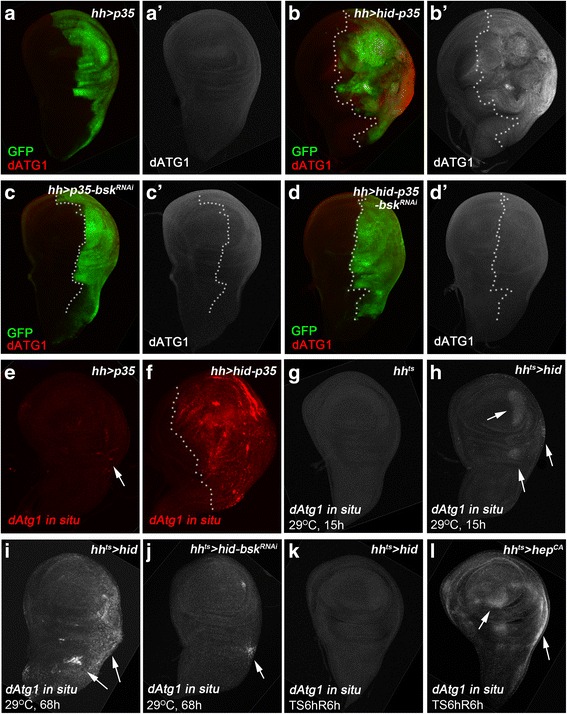

dAtg1 is transcriptionally induced for AiP in a JNK-dependent manner

Next, we examined if protein and transcript levels of dAtg1 change in AiP. Indeed, using a dATG1-specific antibody (Additional file 1: Figure S1B, C) [71], we observed increased protein abundance of dATG1 in the undead compartment of wing discs compared to controls (Fig. 5a, b). To determine if this is a transcriptional or translational effect on dATG1 levels in undead cells, we performed mRNA in situ hybridization assays on undead (hh > hid-p35) and regenerative (hhts > hid) wing imaginal discs. In both AiP models, dAtg1 is transcriptionally induced (Fig. 5e–i). Additional file 5: Figure S5 demonstrates the specificity of the dAtg1 in situ probes. The hhts > hid regenerative model allows determination of the timing of dAtg1 expression during AiP. dAtg1 expression is slow as a pulse of hid expression for 15 h only weakly induces it (Fig. 5h). Only after prolonged expression of hid (68 h), is a strong induction of dAtg1 expression detectable (Fig. 5i). These data suggest that dAtg1 expression occurs quite late in the AiP response.

Fig. 5.

dAtg1 is transcriptionally induced for AiP in a JNK-dependent manner. Late third instar wing discs, anterior is to the left. White dotted lines indicate the anterior/posterior compartment boundaries. hh-Gal4 is used to drive expression of various transgenes in the posterior compartment of wing discs. (a–d’) Wing discs are labeled with dATG1 (red in a, b, c, d and grey in a’, b’, c’, d’). GFP marks the posterior disc compartment where hh-Gal4 is expressed (green in a, b, c, d). Compared to hh > p35 controls (a, a’), co-expression of hid and p35 by hh > Gal4 induces overgrowth of the posterior wing compartment as indicated by enlarged tissue size and folded disc morphology (b, b’). dATG1 protein is strongly increased in the overgrown posterior tissue (compare b’ to a’). Knockdown of JNK (bsk RNAi) has no effect on dATG1 expression in the control hh > p35 discs (c, c’), but it suppresses overgrowth as well as accumulation of dATG1 in hh > hid-p35 discs (compare d, d’ to b, b’). (e–l) Wing discs labeled with dAtg1 in situ antisense probes (red in e, f and grey in g–l). (e, f) Compared to the control (e), dAtg1 transcription, as indicated by the fluorescent in situ signals of dAtg1, is increased in hh > hid-p35 discs (f). (g–l) hh-Gal4 tub-Gal80 ts (hh ts) was used to control temporal expression of GAL4 alone as the control (g), hid (h, i, k), hid and bsk RNAi (j), or a constitutively activated form of JNK kinase, hep CA (l). A weak increase of dAtg1 transcript was observed in the posterior wing tissues after a 15 h expression of hid (h, arrows). dAtg1 transcript is strongly increased after hid expression for 68 h (i, arrows). This increase of dAtg1 transcripts is inhibited by knockdown of JNK (bsk RNAi) with only a low level of dAtg1 induction left in hh ts > hid,bsk RNAi discs (j, arrow, compared to i). Although expression of hid at 29 °C for 6 h followed by recovery at 18 °C for 6 h (TS6hR6h) does not trigger accumulation of dAtg1 (k), expression of hep CA (to activate JNK) under the same condition is sufficient to induce expression of dAtg1 (l, arrows)

Because dAtg1 acts genetically downstream of or in parallel to JNK (Figs. 3 and 4) and because JNK can induce dAtg1 expression under oxidative stress conditions and by ectopic activation of JNK [72], we tested if the transcriptional induction of dAtg1 in the AiP models is also dependent on JNK. The Drosophila JNK homolog is encoded by the gene basket (bsk) [73, 74]. Indeed, while bsk RNAi does not affect dAtg1 expression in control discs (Fig. 5c, c’), it suppresses the accumulation of dATG1 protein in undead and dAtg1 transcripts in regenerative wing discs (Fig. 5d, d’, j). Consistent with a previous report [72], ectopic JNK activation by expression of a constitutively active JNKK transgene (hepCA) for a short pulse of 6 h with 6 h recovery at 18 °C (TS6hR6h) is sufficient to induce dAtg1 expression in wing imaginal discs (Fig. 5l). However, expression of the pro-apoptotic gene hid under the same conditions (TS6hR6h) cannot induce dAtg1 expression (Fig. 5k). Combined, these data suggest that dAtg1 expression is under direct control of JNK signaling, while it is far downstream of Hid expression.

Undead tissue produces autophagosome-like particles which do not contribute to apoptosis-induced proliferation

dAtg1 acts upstream in the autophagy pathway and its activation can induce autophagy [6, 10, 17]. Oxidative stress or ectopic activation of JNK has been previously reported to induce expression of multiple dAtg genes, including dAtg1, as well as autophagy in midgut and fat body cells [72]. We therefore examined if autophagy is induced in undead disc tissue and whether it contributes to AiP. Because dATG8 is an essential part of autophagosomes, fusion proteins of dATG8 with fluorescent proteins such as GFP or mCherry are used as markers for formation of autophagosomes [7]. Moreover, because GFP is stable in autophagosomes, but unstable in autolysosomes, whereas mCherry is stable in both compartments, the tandem fusion protein GFP-mCherry-dATG8a is used as marker for the maturation of autophagosomes into autolysosomes, indicating autophagic flux [75, 76]. Indeed, as shown in Additional file 6: Figure S6, undead ey > hid-p35-expressing tissue accumulates large quantities of GFP-mCherry-dATG8a-containing particles. However, it is unclear if these particles are classical autophagosomes. While the GFP signals are weaker compared to the mCherry signals, which may be an indicator of autophagic flux, there are clearly GFP-only particles which do not display mCherry fluorescence (compare Additional file 6: Figure S6b’ and S6b”). This observation is inconsistent with the concept of autophagic flux [75]. Furthermore, even though dAtg1 RNAi suppresses AiP, it does not suppress the formation of the GFP-mCherry-dATG8a particles (Additional file 6: Figure S6C–C”). This result suggests that the ectopic expression of dAtg1 in undead tissue does not induce the formation of the GFP-mCherry-dATG8a-containing particles. Furthermore, and more importantly, these particles do not contribute to the overgrowth of undead tissue nor, thus, to AiP.

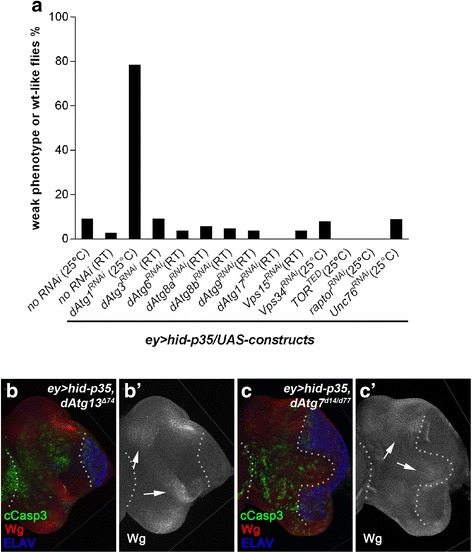

Other dAtg genes mediating autophagy and unc-76 are not required for apoptosis-induced proliferation

Because of this unexpected result, we tested other dAtg genes for an involvement in AiP. Surprisingly, RNAi targeting dAtg3, dAtg6, dAtg8a, dAtg8b, dAtg9, and dAtg17 as well as vps15 and vps34 had no effect on AiP (Fig. 6a). Most notable are dAtg3 and dAtg8 because they encode essential components for autophagosome maturation (see Background) [3, 19–21]. To ensure that the RNAi transgenes used to target these dAtg genes are functionally intact, we tested them in two functional assays. They suppressed starvation-induced autophagy in the fat body (Additional file 7: Figure S7A–E’) demonstrating that dAtg3, dAtg8a, and dAtg8b are efficiently knocked down to induce an autophagy-deficient phenotype. In addition, the functionality of these RNAi stocks is further confirmed in that they all enhanced the eyeful phenotype (Additional file 4: Figure S4F–J) which is known to be enhanced by loss of autophagy [77]. The eyeful (ey-Gal4 UAS-Dl,psq,lola) [78] condition uses the same Gal4 driver as in the ey > hid-p35 AiP model. Therefore, tissue-specific and/or Gal4-dependent differences do not account for the failure of these RNAi stocks to suppress AiP.

Fig. 6.

Key components of the autophagy pathway, other than dAtg1, do not modify the ey > hid-p35 phenotype. (a) Results of the suppression of ey > hid-p35 using RNAi targeting components of the autophagy pathway in Drosophila. Representative RNAi results for each gene were shown. Compared to the control where no RNAi was used, knockdown of dAtg1 significantly increases the percentage of weak phenotype or wildtype-like ey > hid-p35 flies to about 80 %. However, knockdown of dAtg3, dAtg6, dAtg8a, dAtg8b, dAtg9, dAtg17, vps15, and vps34 does not suppress the ey > hid-p35 overgrowth phenotype. In contrast, expression of a kinase dead form of TOR (TORTED) or knockdown of raptor, both of which cause activation of dAtg1, enhances the AiP phenotype. However, RNAi targeting unc-76, which mediates the function of dAtg1 in neuronal development, does not suppress the overgrowth of ey > hid-p35 flies. Room temperature (RT) was used in some cases due to strong lethality caused by expressing these RNAi lines at 25 °C in the background of ey > hid-p35. The ey > hid-p35 flies display comparable overgrowth phenotypes at 25 °C and RT. (b–c’) Late third instar eye discs labeled with cCasp3, Wg, and ELAV. Neither dAtg13 null mutants (dAtg13 Δ74) (b, b’) nor dAtg7 null mutants (dAtg7 Δ14/ dAtg7 Δ77) (c, c’) inhibit overgrowth, cCasp3 labeling and ectopic Wg expression (b’, b’; arrows) in ey > hid-p35 discs (at least 40 discs were analyzed for each genotype)

In addition to targeting essential autophagy components by RNAi, we also tested homozygous dAtg13 and dAtg7 mutants which can survive to pupal or adult stages, respectively, for suppression of AiP. dAtg13 encodes a component of the ATG1/ULK protein complex, while dAtg7 encodes the E1-conjugating enzyme for autophagosome maturation. However, dAtg13 and dAtg7 mutants fail to suppress the abnormal morphology of ey > hid-p35 discs as visualized by ELAV labeling and the ectopic Wg expression (Fig. 6b, c). These results suggest that the tested dAtg genes, except dAtg1, are not required for AiP. An involvement of dAtg1 in AiP is further confirmed by expression of a kinase dead form of TOR (TORTED) [79], which activates dAtg1 [7], or RNAi knockdown of Raptor, an adaptor protein required for TOR activation [80], both of which enhance AiP (Fig. 6a).

Finally, we also examined the possibility that dAtg1 uses the same mechanism in AiP that it uses during neuronal development. However, RNAi targeting unc-76, which is an important mediator of the function of dAtg1 during neuronal development [27], does not suppress the overgrowth phenotype of the undead ey > hid-p35 AiP model (Fig. 6a). Three independent RNAi lines gave consistent results. Therefore, in addition to autophagy and neuronal development, our data define a third function of dAtg1 for AiP.

Discussion

In this paper, we show that the sole ULK ortholog in Drosophila, dAtg1, is required for AiP both in undead and regenerative models. We demonstrated that dAtg1 acts downstream of JNK activity in AiP and is transcriptionally induced by JNK, consistent with a previous study on oxidation response [72]. Furthermore, dAtg1 is required for the expression of Wg, a mitogen associated with AiP [51, 52, 54–56, 81]. Finally, our data provide evidence that the role of dAtg1 in AiP is independent on its role in canonical autophagy.

It is generally assumed that the secreted mitogens Wg, Dpp, and Spitz promote the proliferation of surviving cells during AiP [43, 45]. The expression of these genes is under control of JNK activity. Until recently, it was unknown how JNK signaling promotes expression of these genes. However, very recently, it was reported that an enhancer element in the wg gene that drives expression of wg under regenerative conditions contains three AP-1 binding sites required for regeneration [81]. AP-1 is composed of the transcription factors Jun and Fos (Kayak in Drosophila), which are controlled by JNK activity. This observation suggests a direct way of wg expression by JNK-dependent AP-1.

How does dATG1 fit into the AiP network? Our genetic data suggest that dAtg1 acts downstream of or in parallel to JNK. Furthermore, we placed dAtg1 genetically upstream of wg expression. Therefore, dAtg1 may act in at least two different ways in the AiP network. It may directly modulate the activity of the AP-1 transcriptional complex. An indirect mode of action is also possible in which dATG1 provides a permissive environment for AP-1 activity. However, dAtg1 does not control all AP-1 activities. Expression of puc-lacZ and MMP-1 are not affected by dAtg1RNAi and dAtg1 mutants, respectively (Figs. 3 and 4). In contrast, wg expression is suppressed under these conditions. Therefore, of the known transcriptional targets of JNK and AP-1 during AiP (puc-lacZ, MMP-1, dAtg1, and wg), dAtg1 affects only wg expression. Future work will address the mechanistic role of dATG1 for the control of AiP.

Although dAtg1 is required for AiP, it is not sufficient. Overexpression of dAtg1 using DEts-Gal4 for 12 h followed by 24 h recovery does not trigger AiP markers such as wg-lacZ, dpp-lacZ, or kek-lacZ (Additional file 4: Figure S4). Expression of hid under the same conditions is able to induce these markers ectopically. These observations suggest that, in addition to dAtg1 expression, apoptotic signaling triggers an additional activity required for wg expression and AiP.

The best characterized function of dATG1 and of ULKs in general is the initiation of autophagy under starvation or stress conditions [1, 2, 5, 10, 72]. Autophagy requires a total of 36 Atg genes [3]. Although we did not test all 36 dAtg genes for a role in AiP, we tested several genes which are critical for autophagy, including dAtg3, dAtg6, dAtg7, dAtg8, dAtg9, dAtg13, dAtg17, and vps34. dAtg13 and dAtg17 (aka Fip200) encode subunits of the ATG1/ULK complex [10–12]. ATG6 and VPS34 are subunits of the ATG6/Beclin complex, which is activated by ATG1 during autophagy. Phosphorylation of ATG9, the mammalian ortholog of dATG9, by ULK1 is required for autophagy [16, 17]. Finally, lipidation of ATG8, which is essential for formation of autophagosomes requires the function of ATG3 and ATG7 [3, 20, 21]. In contrast to dAtg1, inactivation of any of these genes does not suppress the overgrowth phenotype of ey > hid-p35 animals. Furthermore, although we detect the formation of ATG8a-containing particles in undead eye imaginal discs, these particles are not dependent on dAtg1 and do not contribute to AiP and overgrowth (Additional file 6: Figure S6). Combined, these data suggest that dATG1 does not trigger canonical autophagy in an AiP context.

In addition to autophagy, ULK proteins have also been implicated in neuronal development, most notably axon guidance and axonal growth [27, 30]. However, we also exclude a neuronal function of dAtg1 in AiP because inactivation of unc-76, a mediator of dAtg1 for neuronal development [27], does not suppress overgrowth induced by ey > hid-p35.

Conclusions

We revealed a third function of dAtg1 in Drosophila for the control of regenerative proliferation after massive apoptotic cell loss. Future work will address if this role of dAtg1 in regenerative proliferation is also conserved in other organisms, the molecular mechanism of this function, and whether it is potentially misregulated in pathological conditions such as cancer.

Methods

Fly strains and the ey > hid-p35 assay

UAS-dAtg1[KQ#5B] or UAS-dAtg1[K38Q] were used to express an dAtg1 kinase-dead mutant that functions as a dominant negative [6]. Either UAS-dAtg16B or UAS-dAtg1GS10797 were used to express wildtype dAtg1 [6]. Both constructs gave similar results under the control of Gal4 lines tested in this study. Dorsal Eye-Gal4 (DE-Gal4) [66], droncI29 [82], dAtg1Δ3D [7], dAtg13Δ7 [10], dAtg7d14, dAtg7d77 [83], dAtg8a::GFP-mCherry-dAtg8a [76], and eyeful (ey-Gal4 > UAS-delta, GS88A8 UAS-lola and UAS-pipsqueak) [78] were as described. puc-lacZE69, wg-lacZ, dpp-lacZ, kek-lacZ, ey-Gal4, hh-Gal4, nub-Gal4, GMR-Gal4, tub-Gal80ts, UAS-p35, UAS-hid, UAS-hepCA, UAS-GFP, and UAS-TORTED were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. UAS-based RNAi stocks of the following genes were obtained from Bloomington, VDRC or NIG-FLY stock centers: bsk (BL 32977, V34138), dAtg1 (BL26731), dAtg3 (BL34359, V101364), dAtg6 (V22122, V110197), dAtg8a (V43076, V43097), dAtg8b (V17097), dAtg9 (V10045), dAtg17 (V106176), Vps15 (V110706, NIG9746R-2), Vps34 (V100296), raptor (BL34814, BL41912), and unc-76 (V20721, V20722, V40495). Comparable results were obtained from multiple RNAi lines targeting the same gene. Functionality of BL26731, V101364, V43097 and V17097 was tested on inhibition of starvation-induced autophagy [7] (Additional file 7: Figure S7). The exact genotype of ey > hid-p35 is either UAS-hid; ey-Gal4 UAS-p35 (UAS-hid on X; ey-Gal4 UAS-p35 on second chromosome) or UAS-hid; ey-Gal4 UAS-p35 (UAS-hid on X; ey-Gal4 UAS-p35 on third chromosome; only used in Fig. 6c, c’). For analysis of ey > hid-p35 adult hyperplastic phenotype, three categories, weak (W), moderate (M) and severe (S), were used as previously described [52]. Each screen analysis was repeated at least twice at 25 °C, or at room temperature (RT, 22 °C) if strong lethality was caused by expressing RNAi or dominant-negative mutant constructs at 25 °C in the background of ey > hid-p35, with scoring more than 50 ey > hid-p35/(RNAi or mutant) adult flies.

Temperature-sensitive regenerative assays and statistical analysis

Larvae of the following genotypes (1) DEts > hid (UAS-hid/+; UAS-GFP/+; DE-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts/+); (2) DEts > dAtg1RNAi (UAS-GFP/+; DE-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts/UAS-dAtg1RNAi); (3) DEts > hid-dAtg1RNAi (UAS-hid/+; UAS-GFP/+; DE-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts/UAS-dAtg1RNAi); (4) DEts > dAtg1DN (UAS-GFP/+; DE-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts/UAS-dAtg1DN); (5) DEts > hid-dAtg1DN (UAS-hid/+; UAS-GFP/+; DE-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts/UAS-dAtg1DN) were raised at 18 °C. Expression of UAS-constructs (GFP, hid, dAtg1RNAi, dAtg1DN) was induced by a temporal temperature shift to 29 °C for 12 h. After a 72 h recovery period at 18 °C, late third instar eye discs were dissected and analyzed as indicated in the panels (Fig. 2). Full details of the DEts > hid assay have been described previously [52]. At least three independent experimental repeats were done for each genotype and the results were consistent. For statistical analysis shown in Fig. 2d, at least 10 eye discs from each of the following genotypes, DEts > hid; DEts > dAtg1RNAi; DEts > hid-dAtg1RNAi; DEts > dAtg1DN; and DEts > hid-dAtg1DN, were measured for their sizes of dorsal versus ventral half of discs using the “histogram” function in Adobe Photoshop CS6. For such measurement, location of the optic stalk at the center of the posterior edge of eye disc was used as a landmark to horizontally divide eye discs into dorsal versus ventral halves. The dorsal/ventral size ratio was then calculated for each genotype. The statistical significance was evaluated through a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison test (at least P < 0.01). For the developing wing tissue (Fig. 5), hh-Gal4 tub-Gal80ts (hhts) was used to temporally control expression of UAS-constructs in the posterior compartment of wing discs.

Mosaic analysis

For mosaic analysis with “undead” cell clones in larval discs (Fig. 4), the 3 L-MARCM assay was used [84]. Mid second instar (32–40 h post-hatching) larvae of the following genotypes were heat shocked for 1 h at 37 °C, raised at 25 °C, and analyzed at the late third instar larval stage. (1) Generation of hid and p35 co-expressing “undead” clones: hs-FLP tub-GAL4 UAS-GFP/UAS-hid; UAS-p35/+; tub-GAL80 FRT80B/FRT80B. (2) Generation of hid and p35 co-expressing dronc mutant clones: hs-FLP tub-GAL4 UAS-GFP/UAS-hid; UAS-p35/+; tub-GAL80 FRT80B/droncI29FRT80B. (3) Generation of hid and p35 co-expressing dAtg1 mutant clones: hs-FLP tub-GAL4 UAS-GFP/UAS-hid; UAS-p35/+; tub-GAL80 FRT80B/dAtg1Δ3DFRT80B. (4) Generation of dAtg1 mutant clones in GMR-hid eye discs: ey-FLP/+; GMR-hid/+; dAtg1Δ3DFRT80B/ubi-GFP FRT80B. The mosaic assay in starving fat body (Additional file 7: Figure S7) was done according to Neufeld [85]. UAS-RNAi lines targeting dAtg1, dAtg3, dAtg8a, and dAtg8b were crossed to yw hs-FLP; r4-mCherry-Atg8a Act > CD2 > Gal4 UAS-GFPnls [86] and incubated at 25 °C. Offspring were starved for 3 h on 20 % sucrose solution before dissection.

Immunohistochemistry and quantification of cCasp3 labeling intensity

Imaginal discs were dissected from late third instar larvae and stained using standard protocols [87]. Antibodies to the following primary antigens were used: anti-cleaved Caspase-3 (Cell Signaling), β-GAL, ELAV, MMP1 (3B8D12 and 5H7B1 used as a 1:1 cocktail), and Wg (all DHSB). dATG1 antibodies were kindly provided by Jun Hee Lee [71]. Secondary antibodies were donkey Fab fragments conjugated to FITC, Cy3 or Cy5 from Jackson ImmunoResearch. For the dATG1 labeling, HRP-labeled secondary antibodies were used and amplified with Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA, PerkinElmer). Fluorescent images were taken with a Zeiss confocal microscope. Adult fly images were taken using a Zeiss stereomicroscope equipped with an AxioCam ICC1 camera.

For quantification of cCasp3 labeling intensity in eye or wing discs (Fig. 3j, k and Additional file 3: Figure S3C), the average cCasp3 signal intensities in certain disc areas were acquired through Adobe Photoshop CS6 and normalized to the corresponding background level of cCasp3 labeling in the same disc. The background cCasp3 labeling intensity was obtained from the antenna discs for measurement in eye discs (Fig. 3j), the notum regions for measurement in wing discs (Fig. 3k), and the non-clonal areas for the Additional file 3: Figure S3C. At least five representative discs of each genotype were used for such quantification. The statistical significance was evaluated through either a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison test (at least P < 0.01, Fig. 3j, k) or a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (Additional file 3: Figure S3C).

In situ hybridization

For in situ hybridization to detect dAtg1 transcripts, Drosophila cDNA clone LD18893 (Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project expressed sequence tags, Drosophila Genomic Resource Center) was used as a template to generate digoxigenin-labeled sense and antisense RNA probes (Roche). Labeled probes were detected with a TSA Cy3 kit (PerkinElmer) as previously described [88].

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from 100 eye discs collected from either the control ey-GAL4 or ey-GAL4 UAS-Atg1RNAi (ey > dAtg1RNAi) third instar larvae using the TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA was then generated from 1 μg of total RNA with the GoScript™ Reverse Transcription System (Promega). This is followed by the real-time PCR using the SensiFAST SYBR Hi-Rox kit (BIOLINE) with a ABI Prism7000 system (Life technologies). dAtg1 mRNA levels were normalized to the reference gene ribosomal protein L32 (RPL32) by using the ΔΔCt analysis. Three independent biological repeats were analyzed. The following primers suggested by the FlyPrimerBank [89] were used: dAtg1 Fw, CGTCAGCCTGGTCATGGAGTA; dAtg1 Rv, TAACGGTATCCTCGCTGAG; RPL32 Fw, AGCATACAGGCCCAAGATCG; RPL32 Rv, TGTTGTCGATACCCTTGGGC.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Eric Baehrecke, Georg Halder, Anne-Claire Jacomin, Ioannis Nezis, Jun Hee Lee, the Bloomington Stock Center, the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center in Indiana, the VDRC stock center in Vienna, the NIG-FLY stock center in Kyoto and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) in Iowa for fly stocks and reagents.

Funding

ML is supported by the China Scholarship Council (CSC)-Birmingham joint PhD program. AB is supported by MIRA grant R35 GM118330 from the National Institute of General Medicine Science (NIGMS), USA. YF is supported by Marie Curie Career Integration Grant (CIG) 630846 from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7) and Grant BB/M010880/1 from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), UK. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files). Requests for material should be made to the corresponding authors.

Authors’ contributions

ML, JL, EP and YF carried out the experiments. ML, AB and YF discussed and interpreted the results. AB and YF supervised the project and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Additional files

Specificity of dATG1 antibodies and dAtg1 RNAi. (A) dAtg1 transcript levels were determined by qPCR from total RNA extracted from eye discs without (control) or with expression of dAtg1RNAi driven by ey > GAL4. dAtg1 RNAi suppresses dAtg1 transcript levels to less than 30 %. Error bars represent SD of three biological repeats. (B, B’) A hh > dAtg1 RNAi wing disc labeled with dATG1 antibodies (red in B, grey in B’). Expression of dAtg1 is strongly reduced in the posterior compartment (GFP+) where dAtg1 RNAi is expressed. (C, C’) A GMR > dAtg1 eye disc labeled with dATG1 antibodies (red in C, grey in C’). ATG1 antibodies specifically recognize dATG1 proteins expressed in the GMR domain (GFP+). (TIF 1956 kb)

Expression of dAtg1 enhances caspase activity and apoptosis. Late third instar larval eye discs labeled with the cleaved Caspase-3 antibodies (cCasp3, green in A, B, grey in A’, B’, blue in C, and grey in C’), anterior is to the left. (A–B’) Compared to ey > hid-p35 discs (A, A’), cCasp3 labeling indicating activity of Dronc is not affected by expression of dAtg1 which enhances ey > hid-p35-induced overgrowth phenotype (B, B’). (C–C”’) Expression of dAtg1 under control of DE-Gal4 and tub-Gal80ts (DEts) and indicated by GFP. Expression of dAtg1 by a temperature shift (ts) to 29 °C for 48 h induces apoptosis as indicated by cCasp3 labeling (C’, arrow) and developmental defects in the eye disc indicated by the affected pattern of ELAV labeling (C”, arrow). (TIF 4775 kb)

Loss of dAtg1 does not suppress apoptosis. (A–B’) Mosaic late third instar wing discs with hid-p35-expressing clones positively marked by GFP. Simultaneous expression of hid and p35 in clones induces strong cCasp3 labeling (A, A’, arrows). Similar cCasp3 labeling persists in dAtg1 mutant clones (B, B’, arrows). (C) Quantification of cCasp3 labeling intensity in hid-p35-expressing clones and hid-p35-expressing dAtg1 mutant clones (mean ± SE). No significant difference of cCasp3 labeling was observed. (D–D’) A representative late third instar GMR-hid eye disc with dAtg1 mutant clones negatively marked by GFP (highlighted by yellow dotted lines). The wave of apoptosis (arrow) induced by GMR-hid persists in dAtg1 mutant clones. (E, F) Representative adult eyes of the indicated genotypes. GMR-hid-induced eye ablation phenotype (E) is not altered by RNAi knockdown of dAtg1 (F). (TIF 6416 kb)

Expression of dAtg1 is not sufficient to induce growth signals for AiP. Late third instar eye discs labeled with wg-lacZ (red in B, C and grey in A, B’, C’), dpp-lacZ (red in E, F and grey in D, E’,F’) or kekkon-lacZ (kek-lacZ, red in H, I and grey in G, H’, I’). Anterior is to the left. DE-Gal4 tub-Gal80 ts (DE ts) was used to control expression of UAS-transgenes at 29 °C for 12 h in the dorsal portion of eye discs, followed by 24 h of recovery at 18 °C (TS12hR24h). Compared to control discs (A, D, G), temporal expression of hid leads to apoptosis, indicated by the cCasp3 labeling (green in B), and ectopic induction of wg-lacZ (B’, arrow), dpp-lacZ (E’, arrow) and kek-lacZ (H’, arrow) which are markers of the growth signaling pathways mediating AiP. In contrast, expression of dAtg1 under the same conditions (TS12hR24h) does not activate ectopic wg, dpp or kek (compare C’, F’, I’ to B’, E’, H’) although a low level of apoptosis is induced (cCasp3-labeling, green in C). (TIF 7173 kb)

Specificity of in situ probes to detect dAtg1 transcripts. In situ hybridization of late third instar larval eye discs with DIG-labeled probes detected with Tyramide Signal Amplification. (A) Endogenous dAtg1 is expressed at low level in wildtype eye discs. (B, C) Labeling of GMR > dAtg1 discs using sense probes (B) and anti-sense dAtg1 probes (C). The dAtg1 antisense probes recognize high levels of dAtg1 transcripts driven by GMR-Gal4 (C, the GMR domain expressing dAtg1 is highlighted). (TIF 1140 kb)

(A–C”) Autophagic flux reporter expression in ey > hid-p35 eye discs. Late third instar larval eye discs expressing the autophagic flux reporter GFP-mCherry-dAtg8a under control of the dAtg8 promoter [76]. The yellow dotted lines indicate the anterior portions of the eye discs which expresses ey-Gal4. Note the overgrowth of the anterior eye disc portion in ey > hid-p35 imaginal discs (B–B”). Expression of GFP and mCherry is low in the control ey > p35 discs (A–A”). In contrast, the numbers of GFP and mCherry positive particles are strongly increased in the overgrown ey-Gal4 expressing area of ey > hid-p35 discs (B–B”). Although the overgrowth of ey > hid-p35 eye discs is strongly suppressed by dAtg1 RNAi, the GFP and mCherry signals are not significantly reduced (C–C”). (TIF 7456 kb)

Functional tests of the RNAi lines targeting dAtg1, dAg3, dAtg8a, and dAtg8b. (A–E) Starvation assay of fat bodies from third instar larvae. Formation of autophagosomes was visualized by mCherry-Atg8 (red in A–E; grey in A’–E’). Cells expressing RNAi constructs are labeled by GFP and outlined by yellow dotted lines. (A) Wildtype fat body displaying mCherry-Atg8 puncta both in clone cells and surrounding cells. (B–E) Cells expressing dAtg1, dAtg3, dAtg8a, and dAtg8b RNAi (GFP +) fail to form mCherry-Atg8 marked autophagosomes. The loss of mCherry-Atg8 signals by dAtg8a and dAtg8b RNAi in (D) and (E) also demonstrates that these RNAi lines target mCherry-Atg8 transcripts. (F–J) Adult eyes expressing eyeful and indicated RNAi transgenes. As previously reported [77], loss of autophagy strongly enhances the eyeful phenotype. The functionality of dAtg1, dAtg3, dAtg8a, and dAtg8b RNAi transgenes is confirmed by enhancement of the eyeful phenotype. (TIF 8420 kb)

Contributor Information

Mingli Li, Email: mxl372@student.bham.ac.uk.

Jillian L. Lindblad, Email: jillian.lindblad@umassmed.edu

Ernesto Perez, Email: ernesto.perez@umassmed.edu.

Andreas Bergmann, Email: andreas.bergmann@umassmed.edu.

Yun Fan, Email: y.fan@bham.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Alers S, Loffler AS, Wesselborg S, Stork B. The incredible ULKs. Cell Commun Signal. 2012;10(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan EY. Regulation and function of uncoordinated-51 like kinase proteins. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17(5):775–85. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:107–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsukada M, Ohsumi Y. Isolation and characterization of autophagy-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1993;333(1-2):169–74. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80398-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuura A, Tsukada M, Wada Y, Ohsumi Y. Apg1p, a novel protein kinase required for the autophagic process in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1997;192(2):245–50. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00084-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott RC, Juhasz G, Neufeld TP. Direct induction of autophagy by Atg1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptotic cell death. Curr Biol. 2007;17(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott RC, Schuldiner O, Neufeld TP. Role and regulation of starvation-induced autophagy in the Drosophila fat body. Dev Cell. 2004;7(2):167–78. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meijer WH, van der Klei IJ, Veenhuis M, Kiel JA. ATG genes involved in non-selective autophagy are conserved from yeast to man, but the selective Cvt and pexophagy pathways also require organism-specific genes. Autophagy. 2007;3(2):106–16. doi: 10.4161/auto.3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee EJ, Tournier C. The requirement of uncoordinated 51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) and ULK2 in the regulation of autophagy. Autophagy. 2011;7(7):689–95. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.7.15450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang YY, Neufeld TP. An Atg1/Atg13 complex with multiple roles in TOR-mediated autophagy regulation. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(7):2004–14. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganley IG, Lam du H, Wang J, Ding X, Chen S, Jiang X. ULK1.ATG13.FIP200 complex mediates mTOR signaling and is essential for autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(18):12297–305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900573200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung CH, Jun CB, Ro SH, Kim YM, Otto NM, Cao J, Kundu M, Kim DH. ULK-Atg13-FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(7):1992–2003. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosokawa N, Sasaki T, Iemura S, Natsume T, Hara T, Mizushima N. Atg101, a novel mammalian autophagy protein interacting with Atg13. Autophagy. 2009;5(7):973–9. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.7.9296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hara T, Takamura A, Kishi C, Iemura S, Natsume T, Guan JL, Mizushima N. FIP200, a ULK-interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;181(3):497–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mercer CA, Kaliappan A, Dennis PB. A novel, human Atg13 binding protein, Atg101, interacts with ULK1 and is essential for macroautophagy. Autophagy. 2009;5(5):649–62. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.5.8249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papinski D, Kraft C. Atg1 kinase organizes autophagosome formation by phosphorylating Atg9. Autophagy. 2014;10(7):1338–40. doi: 10.4161/auto.28971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papinski D, Schuschnig M, Reiter W, Wilhelm L, Barnes CA, Maiolica A, Hansmann I, Pfaffenwimmer T, Kijanska M, Stoffel I, et al. Early steps in autophagy depend on direct phosphorylation of Atg9 by the Atg1 kinase. Mol Cell. 2014;53(3):471–83. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang HW, Wang YB, Wang SL, Wu MH, Lin SY, Chen GC. Atg1-mediated myosin II activation regulates autophagosome formation during starvation-induced autophagy. EMBO J. 2011;30(4):636–51. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ichimura Y, Kirisako T, Takao T, Satomi Y, Shimonishi Y, Ishihara N, Mizushima N, Tanida I, Kominami E, Ohsumi M, et al. A ubiquitin-like system mediates protein lipidation. Nature. 2000;408(6811):488–92. doi: 10.1038/35044114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geng J, Klionsky DJ. The Atg8 and Atg12 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems in macroautophagy. ‘Protein modifications: beyond the usual suspects’ review series. EMBO Rep. 2008;9(9):859–64. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie Z, Nair U, Klionsky DJ. Atg8 controls phagophore expansion during autophagosome formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(8):3290–8. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogura K, Wicky C, Magnenat L, Tobler H, Mori I, Muller F, Ohshima Y. Caenorhabditis elegans unc-51 gene required for axonal elongation encodes a novel serine/threonine kinase. Genes Dev. 1994;8(20):2389–400. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.20.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan J, Kuroyanagi H, Kuroiwa A, Matsuda Y, Tokumitsu H, Tomoda T, Shirasawa T, Muramatsu M. Identification of mouse ULK1, a novel protein kinase structurally related to C. elegans UNC-51. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246(1):222–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuroyanagi H, Yan J, Seki N, Yamanouchi Y, Suzuki Y, Takano T, Muramatsu M, Shirasawa T. Human ULK1, a novel serine/threonine kinase related to UNC-51 kinase of Caenorhabditis elegans: cDNA cloning, expression, and chromosomal assignment. Genomics. 1998;51(1):76–85. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aladzsity I, Toth ML, Sigmond T, Szabo E, Bicsak B, Barna J, Regos A, Orosz L, Kovacs AL, Vellai T. Autophagy genes unc-51 and bec-1 are required for normal cell size in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2007;177(1):655–60. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.075762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomoda T, Kim JH, Zhan C, Hatten ME. Role of Unc51.1 and its binding partners in CNS axon outgrowth. Genes Dev. 2004;18(5):541–58. doi: 10.1101/gad.1151204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toda H, Mochizuki H, Flores R, 3rd, Josowitz R, Krasieva TB, Lamorte VJ, Suzuki E, Gindhart JG, Furukubo-Tokunaga K, Tomoda T. UNC-51/ATG1 kinase regulates axonal transport by mediating motor-cargo assembly. Genes Dev. 2008;22(23):3292–307. doi: 10.1101/gad.1734608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogura K, Okada T, Mitani S, Gengyo-Ando K, Baillie DL, Kohara Y, Goshima Y. Protein phosphatase 2A cooperates with the autophagy-related kinase UNC-51 to regulate axon guidance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 2010;137(10):1657–67. doi: 10.1242/dev.050708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahantarig A, Chadwell LV, Terrazas IB, Garcia CT, Nazarian JJ, Lee HK, Lundell MJ, Cassill JA. Molecular characterization of Pegarn: a Drosophila homolog of UNC-51 kinase. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36(6):1311–21. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9314-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mochizuki H, Toda H, Ando M, Kurusu M, Tomoda T, Furukubo-Tokunaga K. Unc-51/ATG1 controls axonal and dendritic development via kinesin-mediated vesicle transport in the Drosophila brain. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wairkar YP, Toda H, Mochizuki H, Furukubo-Tokunaga K, Tomoda T, Diantonio A. Unc-51 controls active zone density and protein composition by downregulating ERK signaling. J Neurosci. 2009;29(2):517–28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3848-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor RW, Qi JY, Talaga AK, Ma TP, Pan L, Bartholomew CR, Klionsky DJ, Moens CB, Gamse JT. Asymmetric inhibition of Ulk2 causes left-right differences in habenular neuropil formation. J Neurosci. 2011;31(27):9869–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0435-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou X, Babu JR, da Silva S, Shu Q, Graef IA, Oliver T, Tomoda T, Tani T, Wooten MW, Wang F. Unc-51-like kinase 1/2-mediated endocytic processes regulate filopodia extension and branching of sensory axons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(14):5842–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701402104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian E, Wang F, Han J, Zhang H. epg-1 functions in autophagy-regulated processes and may encode a highly divergent Atg13 homolog in C. elegans. Autophagy. 2009;5(5):608–15. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.5.8624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gan B, Peng X, Nagy T, Alcaraz A, Gu H, Guan JL. Role of FIP200 in cardiac and liver development and its regulation of TNFalpha and TSC-mTOR signaling pathways. J Cell Biol. 2006;175(1):121–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai T, Garriga G. The conserved kinase UNC-51 acts with VAB-8 and UNC-14 to regulate axon outgrowth in C. elegans. Development. 2004;131(23):5991–6000. doi: 10.1242/dev.01457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogura K, Shirakawa M, Barnes TM, Hekimi S, Ohshima Y. The UNC-14 protein required for axonal elongation and guidance in Caenorhabditis elegans interacts with the serine/threonine kinase UNC-51. Genes Dev. 1997;11(14):1801–11. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.14.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wightman B, Clark SG, Taskar AM, Forrester WC, Maricq AV, Bargmann CI, Garriga G. The C. elegans gene vab-8 guides posteriorly directed axon outgrowth and cell migration. Development. 1996;122(2):671–82. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.2.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogura K, Goshima Y. The autophagy-related kinase UNC-51 and its binding partner UNC-14 regulate the subcellular localization of the Netrin receptor UNC-5 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 2006;133(17):3441–50. doi: 10.1242/dev.02503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomoda T, Bhatt RS, Kuroyanagi H, Shirasawa T, Hatten ME. A mouse serine/threonine kinase homologous to C. elegans UNC51 functions in parallel fiber formation of cerebellar granule neurons. Neuron. 1999;24(4):833–46. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rajesh S, Bago R, Odintsova E, Muratov G, Baldwin G, Sridhar P, Overduin M, Berditchevski F. Binding to syntenin-1 protein defines a new mode of ubiquitin-based interactions regulated by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(45):39606–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.262402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mollereau B, Perez-Garijo A, Bergmann A, Miura M, Gerlitz O, Ryoo HD, Steller H, Morata G. Compensatory proliferation and apoptosis-induced proliferation: a need for clarification. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20(1):181. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryoo HD, Bergmann A. The role of apoptosis-induced proliferation for regeneration and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(8):a008797. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fan Y, Bergmann A. Apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation. The cell is dead. Long live the cell! Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18(10):467–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bergmann A, Steller H. Apoptosis, stem cells, and tissue regeneration. Sci Signal. 2010;3(145):re8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3145re8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haynie JL, Bryant PJ. The effects of X-rays on the proliferation dynamics of cells in the imaginal disc of Drosophila melanogaster. Rouxs Arch Dev Biol. 1977;183:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00848779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chera S, Ghila L, Dobretz K, Wenger Y, Bauer C, Buzgariu W, Martinou JC, Galliot B. Apoptotic cells provide an unexpected source of Wnt3 signaling to drive hydra head regeneration. Dev Cell. 2009;17(2):279–89. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hwang JS, Kobayashi C, Agata K, Ikeo K, Gojobori T. Detection of apoptosis during planarian regeneration by the expression of apoptosis-related genes and TUNEL assay. Gene. 2004;333:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tseng AS, Adams DS, Qiu D, Koustubhan P, Levin M. Apoptosis is required during early stages of tail regeneration in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 2007;301(1):62–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vlaskalin T, Wong CJ, Tsilfidis C. Growth and apoptosis during larval forelimb development and adult forelimb regeneration in the newt (Notophthalmus viridescens) Dev Genes Evol. 2004;214(9):423–31. doi: 10.1007/s00427-004-0417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fan Y, Bergmann A. Distinct mechanisms of apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation in proliferating and differentiating tissues in the Drosophila eye. Dev Cell. 2008;14(3):399–410. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fan Y, Wang S, Hernandez J, Yenigun VB, Hertlein G, Fogarty CE, Lindblad JL, Bergmann A. Genetic models of apoptosis-induced proliferation decipher activation of JNK and identify a requirement of EGFR signaling for tissue regenerative responses in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(1):e1004131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huh JR, Guo M, Hay BA. Compensatory proliferation induced by cell death in the Drosophila wing disc requires activity of the apical cell death caspase Dronc in a nonapoptotic role. Curr Biol. 2004;14(14):1262–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perez-Garijo A, Martin FA, Morata G. Caspase inhibition during apoptosis causes abnormal signalling and developmental aberrations in Drosophila. Development. 2004;131(22):5591–8. doi: 10.1242/dev.01432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perez-Garijo A, Shlevkov E, Morata G. The role of Dpp and Wg in compensatory proliferation and in the formation of hyperplastic overgrowths caused by apoptotic cells in the Drosophila wing disc. Development. 2009;136(7):1169–77. doi: 10.1242/dev.034017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ryoo HD, Gorenc T, Steller H. Apoptotic cells can induce compensatory cell proliferation through the JNK and the Wingless signaling pathways. Dev Cell. 2004;7(4):491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shlevkov E, Morata G. A dp53/JNK-dependant feedback amplification loop is essential for the apoptotic response to stress in Drosophila. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19(3):451–60. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wells BS, Yoshida E, Johnston LA. Compensatory proliferation in Drosophila imaginal discs requires Dronc-dependent p53 activity. Curr Biol. 2006;16(16):1606–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kondo S, Senoo-Matsuda N, Hiromi Y, Miura M. DRONC coordinates cell death and compensatory proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(19):7258–68. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00183-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bergantinos C, Corominas M, Serras F. Cell death-induced regeneration in wing imaginal discs requires JNK signalling. Development. 2010;137(7):1169–79. doi: 10.1242/dev.045559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herrera SC, Martin R, Morata G. Tissue homeostasis in the wing disc of Drosophila melanogaster: immediate response to massive damage during development. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(4):e1003446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rudrapatna VA, Bangi E, Cagan RL. Caspase signalling in the absence of apoptosis drives Jnk-dependent invasion. EMBO Rep. 2013;14(2):172–7. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith-Bolton RK, Worley MI, Kanda H, Hariharan IK. Regenerative growth in Drosophila imaginal discs is regulated by Wingless and Myc. Dev Cell. 2009;16(6):797–809. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun G, Irvine KD. Regulation of Hippo signaling by Jun kinase signaling during compensatory cell proliferation and regeneration, and in neoplastic tumors. Dev Biol. 2011;350(1):139–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McGuire SE, Le PT, Osborn AJ, Matsumoto K, Davis RL. Spatiotemporal rescue of memory dysfunction in Drosophila. Science. 2003;302(5651):1765–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1089035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morrison CM, Halder G. Characterization of a dorsal-eye Gal4 Line in Drosophila. Genesis. 2010;48(1):3–7. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baker NE. Cell proliferation, survival, and death in the Drosophila eye. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12(6):499–507. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2001.0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fan Y, Bergmann A. The cleaved-Caspase-3 antibody is a marker of Caspase-9-like DRONC activity in Drosophila. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17(3):534–9. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Uhlirova M, Bohmann D. JNK- and Fos-regulated Mmp1 expression cooperates with Ras to induce invasive tumors in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2006;25(22):5294–304. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ghiglione C, Carraway KL, 3rd, Amundadottir LT, Boswell RE, Perrimon N, Duffy JB. The transmembrane molecule kekkon 1 acts in a feedback loop to negatively regulate the activity of the Drosophila EGF receptor during oogenesis. Cell. 1999;96(6):847–56. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim M, Park HL, Park HW, Ro SH, Nam SG, Reed JM, Guan JL, Lee JH. Drosophila Fip200 is an essential regulator of autophagy that attenuates both growth and aging. Autophagy. 2013;9(8):1201–13. doi: 10.4161/auto.24811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu H, Wang MC, Bohmann D. JNK protects Drosophila from oxidative stress by trancriptionally activating autophagy. Mech Dev. 2009;126(8-9):624–37. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.06.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Riesgo-Escovar JR, Jenni M, Fritz A, Hafen E. The Drosophila Jun-N-terminal kinase is required for cell morphogenesis but not for DJun-dependent cell fate specification in the eye. Genes Dev. 1996;10(21):2759–68. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sluss HK, Han Z, Barrett T, Goberdhan DC, Wilson C, Davis RJ, Ip YT. A JNK signal transduction pathway that mediates morphogenesis and an immune response in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1996;10(21):2745–58. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, Agholme L, Agnello M, Agostinis P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8(4):445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee TV, Kamber Kaya HE, Simin R, Baehrecke EH, Bergmann A. The initiator caspase Dronc is subject of enhanced autophagy upon proteasome impairment in Drosophila. Cell Death Differ. 2016. Ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Perez E, Das G, Bergmann A, Baehrecke EH. Autophagy regulates tissue overgrowth in a context-dependent manner. Oncogene. 2015;34(26):3369–76. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ferres-Marco D, Gutierrez-Garcia I, Vallejo DM, Bolivar J, Gutierrez-Avino FJ, Dominguez M. Epigenetic silencers and Notch collaborate to promote malignant tumours by Rb silencing. Nature. 2006;439(7075):430–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hennig KM, Neufeld TP. Inhibition of cellular growth and proliferation by dTOR overexpression in Drosophila. Genesis. 2002;34(1-2):107–10. doi: 10.1002/gene.10139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, King JE, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell. 2002;110(2):163–75. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Harris RE, Setiawan L, Saul J, Hariharan IK. Localized epigenetic silencing of a damage-activated WNT enhancer limits regeneration in mature imaginal discs. Elife. 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Xu D, Li Y, Arcaro M, Lackey M, Bergmann A. The CARD-carrying caspase Dronc is essential for most, but not all, developmental cell death in Drosophila. Development. 2005;132(9):2125–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.01790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Juhasz G, Erdi B, Sass M, Neufeld TP. Atg7-dependent autophagy promotes neuronal health, stress tolerance, and longevity but is dispensable for metamorphosis in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2007;21(23):3061–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.1600707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) for Drosophila neural development. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24(5):251–4. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01791-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Neufeld TP. Genetic manipulation and monitoring of autophagy in Drosophila. Methods Enzymol. 2008;451:653–67. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Arsham AM, Neufeld TP. A genetic screen in Drosophila reveals novel cytoprotective functions of the autophagy-lysosome pathway. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e6068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fogarty CE, Bergmann A. Detecting caspase activity in Drosophila larval imaginal discs. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1133:109–17. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0357-3_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fan Y, Bergmann A. Multiple mechanisms modulate distinct cellular susceptibilities toward apoptosis in the developing Drosophila eye. Dev Cell. 2014;30(1):48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hu Y, Sopko R, Foos M, Kelley C, Flockhart I, Ammeux N, Wang X, Perkins L, Perrimon N, Mohr SE. FlyPrimerBank: an online database for Drosophila melanogaster gene expression analysis and knockdown evaluation of RNAi reagents. G3 (Bethesda) 2013;3(9):1607–16. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.007021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files). Requests for material should be made to the corresponding authors.