Abstract

Normal and tumor cells shed vesicles to the environment. Within the large family of extracellular vesicles, exosomes and microvesicles have attracted much attention in the recent years. Their interest ranges from mediators of cancer progression, inflammation, immune regulation and metastatic niche regulation, to non-invasive biomarkers of disease. In this respect, the procedures to purify and analyze extracellular vesicles have quickly evolved and represent a source of variability for data integration in the field. In this review, we provide an updated view of the potential of exosomes and microvesicles as biomarkers and the available technologies for their isolation.

Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) encompass membrane vesicles that are released by most cells into the surrounding microenvironment, and mediate inter-cellular communication at both paracrine and systemic level [1–11]. EVs are a complex group of vesicles. Indeed, extensive efforts from the scientific community have been done to provide names and classification criteria to the different subtypes of EVs. EV preparations are constituted by exosomes, microvesicles (including ectosomes and microparticles) and apoptotic bodies. These vesicles originate from distinct sub-cellular compartments and exist in different proportions depending on the physiological state and cell type of origin. Although no consensus on marker classification has been established to differentiate EVs [12, 13], exosomes are defined as endosome-originated membrane vesicles with a diameter of 40–150 nm [14], microvesicles refer to plasma membrane shedding vesicles of 0,1–1 μm (ectosomes within this group range from 0,1–0,5 μm) [15, 16] and apoptotic bodies are originated from cells undergoing apoptosis and generally present bigger size [16]. The differential origin of EVs determines their specific cargos, including proteins and nucleic acids [16, 17]. The cargo will have both a passive and active impact on the functionality of EVs, and will constitute a molecular fingerprint representative of the cell of origin. To date, the majority of biological functions ascribed to EVs have been studied by upon isolation from cell cultures or from biological fluids (blood, urine and saliva) [17–20]. Given the significant presence of EVs in most, if not all, bodily fluids, they have been postulated as new potential biomarkers for a wide range of diseases, including cancer [21–26]. Cancer-derived vesicles isolated from liquid biopsies have the potential to be used as a novel clinical tool for refining cancer diagnosis, for therapeutic stratification as well as for monitoring therapy response and outcome prediction (metastasis). However, both the variety and technical complexity of methods used for vesicle isolation make the use of EVs in clinical practice a challenge.

In this review, we provide a perspective on the activities of EVs and discuss the improvement in isolation techniques as well as their potential use as cancer biomarkers.

EVs as non-invasive source for biomarker discovery

Cancer-derived EVs have inherited potential to be used as biomarkers because of their ubiquitous presence in biofluids [17, 27–29]. The characterization of cancer-derived EVs, and in particular their molecular cargo, has emerged as source of circulating information to detect cancer and predict tumor progression and metastasis. Indeed, cancer-derived EVs have been reported as clinical markers aiding the diagnosis of many cancer malignances. In ovarian and pancreatic cancer, the exosome pool found in circulation is increased [24, 30], whereas in prostate cancer a decrease in urine EVs has been observed when compared to benign hyperplasia specimens [25]. In vitro and in vivo pre-clinical studies have incremented our understanding on how the tumor specific cargo of cancer-derived exosomes can provide information about the pathophysiological status of cancer patients, by representing a bioprint of the primary tumor [24–26] as well as a detection and monitorization tool [7, 31].

EVs are composed of a lipid bilayer and contain a cargo that includes all known molecular constituents of a cell: proteins, lipids, microRNA, mRNA and DNA [8, 10, 32, 33]. Whereas membrane composition of cancer-derived EVs may offer unique insights, recent studies have highlighted the importance of the cargo (metabolites, proteins and nucleic acids) for this purpose. The differential presence of nucleic acids in cancer-derived exosomes is a relievable source of biomarkers for several cancers, such as glioblastoma, bladder, liver, colorectal, lung and prostate, as well as brain and melanoma metastasis [26, 34–38]. Cancer-derived exosomes contain double-stranded DNA [32, 39–41] and tumor-specific mutations can be detected in circulating EVs isolated from cancer patients, both in isolated DNA [39, 40], and RNA (EGFRvIII mutation in glioblastoma, [26]).

mRNA from EVs recapitulates to a certain extent the transcriptional landscape of the tumor. We have shown that urinary EVs mRNA cargo can discriminate prostate cancer patients and differentiate them from patients with benign disease [25]. We have observed that specific transcripts exhibit differential abundance in EVs isolated from urine. Some of these transcripts have differential abundance reminiscent of the prostate tumor. As an example, down-regulation of placental Cadherin (CDH3) in tumor tissue is recapitulated in mRNA from urine EVs [42]. This observation could open a new avenue on non-invasive characterization of transcriptional alterations with prognostic or therapeutic implications. Indeed, urine exosome gene expression has been recently proposed as a novel non-invasive approach to differentiate patients with higher-grade prostate cancer among men with elevated PSA levels, thus reducing the number of unnecessary biopsies [43].

In the recent years it has been extensively reported the presence of specific microRNAs (miRs) in EVs, which are informative for the diagnosis and monitoring of cancer progression. miRs are small double-stranded RNAs with strong regulatory potential [44] and its differential abundance in cancer-derived EVs have been associated with the presence and aggressiveness of squamous cell carcinoma, prostate and bladder cancer, among others [22, 30, 34–36, 45–55]

EVs can carry protein in their membrane or in the lumen, representing the tumor proteomic cargo. Differences in EV-protein content from cancer patients have been described in several tumor types [3, 7, 24, 31, 56, 57]. The diagnostic potential of EV-protein content is well-illustrated in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and melanoma. The expression of the surface proteoglycan glypican-1 (GPC-1) in cancer-derived exosomes is ascribed to the cancerous state and can discriminate patients with PDAC from those with benign pancreatic disease [24]. In melanoma, the abundance of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and its phosphorylated form are increased in cancer-derived exosomes when compared with healthy donors [7]. More recently, exosomal tumor-secreted integrins have been postulated as identifiers of the metastatic organotropism [31]. Lyden and colleagues have demonstrated that the enrichment of specific integrin heterodimers in circulating exosomes could predict metastatic organotropism in breast cancer and pancreatic patients. In this work, exosomal integrins α6β4 and α6β1 were associated with lung metastasis, while exosomal integrin αvβ5 was linked to liver metastasis. This data represents a novel strategy to predict metastasis in liquid biopsies [31].

The characterization of EV cargo is still in its infancy. EVs research has shifted our expectations of liquid biopsy as a source of biomarkers [58]. With the advent of high-resolution/high-sensitivity genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics technologies, we envision that the next decade will consolidate non-invasive cell-free biomarkers as the tour de force of cancer diagnosis.

The refinement in EVs isolation methods

As discussed above, EVs are carriers of tumoral molecular information. However, a confounding factor in these studies is the heterogeneity of isolation procedures and the lack of consensus, which impacts on the reproducibility, yield or types of EVs that are isolated in each study. In order to select or develop an EVs isolation procedure for a specific application, several factors should be considered, such as sample nature (cell culture vs biological fluids), sample volume, the desired degree of purity, and the final use intended for the isolated vesicles.

In 2006, Thery and collaborators published a compendium of guidelines to isolate and characterize EVs from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids [59]. The protocols included purification routines that ranged from differential ultracentrifugation coupled to sucrose gradients, to immunocapture using antibodies against exosomal membrane proteins [59]. However, due to the exponential increase of the field in the recent years, new technical solutions have emerged to overcome the intrinsic limitations in the study of EVs.

Differential ultracentrifugation (coupled or not to density gradients) is the most extended and standardized procedure. This method is compatible with processing large sample volumes and allows obtaining preparations enriched in big EVs (mostly microvesicles) or small EVs (mostly exosomes) based on the use of 10,000 x g and 100,000 x g centrifugation forces, respectively [16, 46]. In addition, when ultracentrifugation is performed on sucrose or idioxanol density gradients, further separation of the different subpopulations of vesicles is achieved. Despite the fact that differential ultracentrifugation could cause some “damage” to the EV integrity in terms of vesicles breakage, fusion or aggregation, so far this method is the most commonly employed for “omics”-based molecular and functional analyses. However, from a clinical point of view, ultracentrifugation presents several technical limitations for its practical implementation. In that sense, several alternatives have reached the market with distinct strength and weaknesses:

Polymer-based isolation systems

Most of these products are based on polymers adapted from virus-based studies [60, 61]. Although these methods are not suitable to produce pure preparations of EVs, from a diagnostic perspective they are acceptable to analyze molecules that have been previously associated to extracellular vesicles. Among these, Exoquick (System Biosciences) and Total Exosome Isolation kits (Life technologies) have cornered the market. However, a new contender, Urine Exosome RNA Isolation Kit (NORGEN, Biotek Corp.), offers high-resolution and sensitivity [62, 63]. It is worth noting that NORGEN kit allows the purification of proteins, as recently shown by our group [25]. The introduction of these new methods have led to the concern of a bias in the type of EVs that are enriched with each approach, which could increase the inconsistency among different studies [25, 64]. Importantly, the presence of polymers could interfere with some of the analysis downstream, such as LC/MS-based techniques [65, 66] or functional studies as well as carry soluble factor contaminants that should be determined and characterized in every model tested.

Filtration systems

Ultra-filtration and gel-filtration chromatography (based on sepharose columns for size-exclusion chromatography (SEC)) have been reported to be efficient, quick and able to achieve results comparable to standard methods [67–69]. These techniques are effective in removing contaminant proteins, and they can be applied downstream of other methods. Remarkably, an increasing number of laboratories are incorporating the SEC procedure in their studies mainly due to the low level of contaminants obtained in the EVs preparations. In particular, the SEC-based procedure has been very successful for the analysis of plasma EVs [70]. However, this technique can only be performed with relatively small volumes. For big volumes, other filtration-based approaches have been developed including the hydrostatic dialysis, a technique that has been proposed to analyze and banking urine samples [71].

Affinity methods

Affinity methods specifically separate EVs by their surface proteins. Nowadays, there are a variety of commercial immunoprecipitation kits for a range of proteins, such as Cd81 or Cd63, which allows a more specific isolation of EVs subpopulations, with limitations in their discriminative capacity [59, 72]. In addition, ELISA-based methods [73], Exosearch [74] and the Immunochip [75] allow an specific quantification of subpopulation of EVs for a large number of samples. Recently, high-resolution flow cytometry has been developed as an interesting alternative to characterize and quantify different subpopulations of EVs [76, 77], and for sorting a subset of EVs based on specific surface molecules [78] It is worth noting the potential applicability of lectin [79] or heparin [33]-based systems for detection and isolation of EVs based on surface protein glycosylation.

Towards the production of EVs for therapeutic purposes

Several studies support the use of EVs for delivery of molecular cargo and related signaling [80–82]. These ideas have expanded since the description of key molecules, such as integrins, determining the organ-targeted distribution of tumor-secreted exosomes [31]. Production of clinical-grade exosomes classically require well-established methods of microfiltration, ultrafiltration, and a rapid one-step ultracentrifugation into a discontinuous gradient consisting of 30% sucrose/deuterium oxide (98%) [83]. More recently, the use of EVs as a carrier of selected siRNAs has attracted the interest of researchers and a detailed protocol based on ultracentrifugation has been established [84]. As the field of exosome research grows, therapeutic applications and GMP-grade purification methods are expected to be refined. Thus, in order to progress towards clinical trials, several topics should be considered: EV source, EV characterization and storage strategies, pharmaceutical quality control requirements and in vivo analyses of EVs [82]. One of the main limitations of this field is that the majority of studies reporting tissue and location-specific distribution of EVs are restricted to tumor-derived vesicles. Therefore, further research on EVs derived from normal tissues and their characteristics is warranted. Using tissue-derived EVs as a new field in regenerative medicine could be one of the main areas that will be developed during the next years.

In summary, most of the existing procedures harvest a mix of EVs. Due to the intrinsic heterogeneity of these vesicles, the isolation procedure needs to be carefully considered, since it could deeply impact on the final outcome of the study.

Concluding remarks

Our current knowledge on what EVs do and how they recruit their cargo is limited. We are still far from clinical use of these vesicles as biomarkers of disease. However, EVs, exosomes and microvesicles in particular, present features that make them ideal candidates for liquid biopsy-based biomarkers. On the one hand, they are tissue-specific, which is one of the essential characteristics of biomarkers. On the other hand, they carry and protect the cargo from their tissue of origin, hence representing a bioprint of both physiological and pathological scenarios. However, there are also challenges that the field needs to face. We need to understand and define the heterogeneity of EVs and their associated cargo, and develop specific and reliable methods to work with well-defined preparations. In addition, the EV scientific community is also in urgent need of reaching a consensus regarding the isolation procedures and characterization [85], so that the field can integrate the observations coming from different research groups. The last challenge is to define to which extent EVs are a reflection of the molecular landscape of cancer that can be applied to precision medicine. We learn as we grow, and we need further knowledge and technological development in the field of EVs. These light and shadows predict an exciting bright future for EVs and their applicability in liquid biopsy.

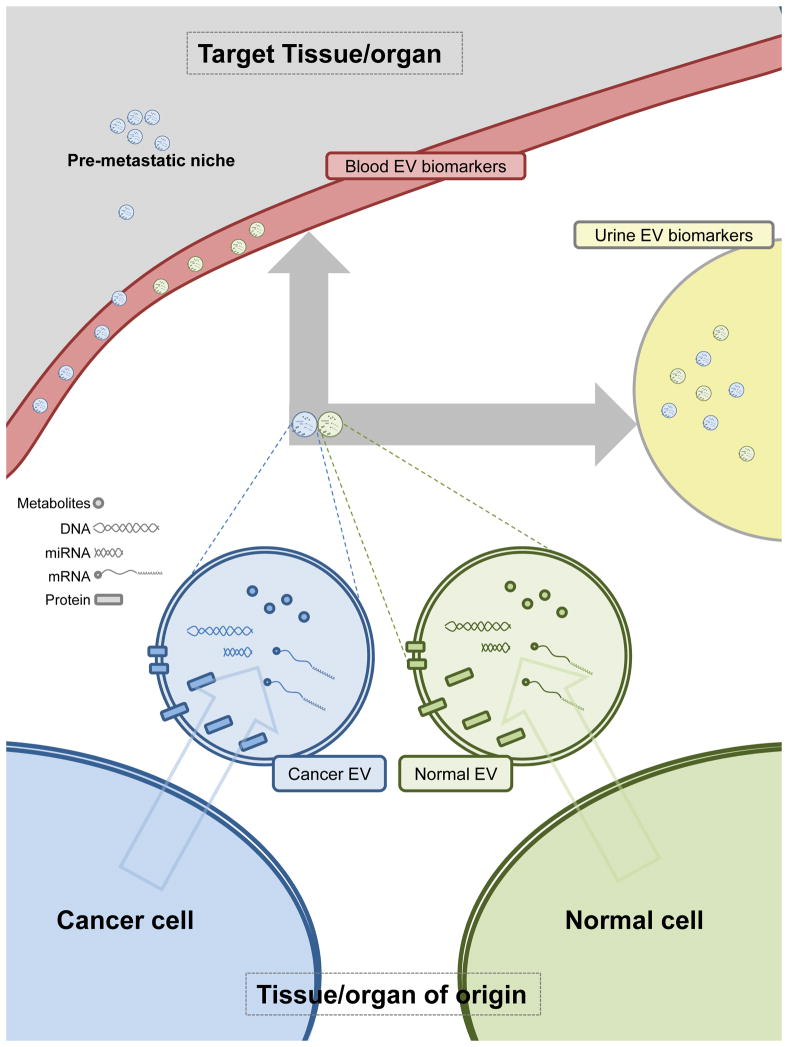

Figure 1. Schematic representation of extracellular vesicles (EVs) as biomarkers in liquid biopsy.

The distinct composition of EVs and its cargo in normal and cancer cells is indicated by differential coloring. Shedding of EVs to blood and urine is depicted (note that urine accessibility will be organ-dependent). The potential of cancer-EVs to educate the pre-metastatic niche is represented as the accumulation of vesicles in target organs.

Highlights.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are secreted virtually by all cell types and vary in cargo and composition

Cancer cells exhibit altered EV composition

The presence of EVs in biofluids support applicability as biomarkers for cancer detection, monitoring or classification

The improvement in EV isolation tools is a critical step in the future use of these particles as biomarkers

Acknowledgments

Apologies to those whose related publications were not cited due to space limitations. The work of AC is supported by the Ramón y Cajal award, the Basque Department of Industry, Tourism and Trade (Etortek), health (2012111086) and education (PI2012-03), Marie Curie (277043), Movember GAP1 project, ISCIII (PI10/01484, PI13/00031), FERO VIII Fellowship and the European Research Council Starting Grant (336343). The work of JF-P is supported by Ramon Areces Foundation, ISCIII (PI12/01604), MINECO (SAF2015-66312) and Health Basque Government (2015111149). HP is supported by grants from MINECO (SAF2014-54541-R), ATRES-MEDIA – AXA, Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer, NIH (RO1 CA169416 ) and DOD.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boelens MC, et al. Exosome transfer from stromal to breast cancer cells regulates therapy resistance pathways. Cell. 2014;159(3):499–513. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai Z, et al. Activated T cell exosomes promote tumor invasion via Fas signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2012;188(12):5954–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3**.Costa-Silva B, et al. Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(6):816–26. doi: 10.1038/ncb3169. Elegant study showing the activity of exosomes in systemic communication and their potential use as clinical markers in pancreatic cancer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hood JL, San RS, Wickline SA. Exosomes released by melanoma cells prepare sentinel lymph nodes for tumor metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71(11):3792–801. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luga V, et al. Exosomes mediate stromal mobilization of autocrine Wnt-PCP signaling in breast cancer cell migration. Cell. 2012;151(7):1542–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pegtel DM, et al. Functional delivery of viral miRNAs via exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(14):6328–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914843107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peinado H, et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat Med. 2012;18(6):883–91. doi: 10.1038/nm.2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ratajczak J, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived microvesicles reprogram hematopoietic progenitors: evidence for horizontal transfer of mRNA and protein delivery. Leukemia. 2006;20(5):847–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salomon C, et al. Hypoxia-induced changes in the bioactivity of cytotrophoblast-derived exosomes. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valadi H, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):654–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11*.Zomer A, et al. In Vivo imaging reveals extracellular vesicle-mediated phenocopying of metastatic behavior. Cell. 2015;161(5):1046–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.042. In vivo evidence showing local and systemic transfer of exosome cargo between tumor cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalra H, et al. Vesiclepedia: a compendium for extracellular vesicles with continuous community annotation. PLoS Biol. 2012;10(12):e1001450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gyorgy B, et al. Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68(16):2667–88. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0689-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathivanan S, Ji H, Simpson RJ. Exosomes: extracellular organelles important in intercellular communication. J Proteomics. 2010;73(10):1907–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cocucci E, Racchetti G, Meldolesi J. Shedding microvesicles: artefacts no more. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19(2):43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crescitelli R, et al. Distinct RNA profiles in subpopulations of extracellular vesicles: apoptotic bodies, microvesicles and exosomes. J Extracell Vesicles. 2013;2 doi: 10.3402/jev.v2i0.20677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol. 2013;200(4):373–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colombo M, Raposo G, Thery C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:255–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minciacchi VR, Freeman MR, Di Vizio D. Extracellular vesicles in cancer: exosomes, microvesicles and the emerging role of large oncosomes. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;40:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thery C. Exosomes: secreted vesicles and intercellular communications. F1000 Biol Rep. 2011;3:15. doi: 10.3410/B3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thery C. Cancer: Diagnosis by extracellular vesicles. Nature. 2015;523(7559):161–2. doi: 10.1038/nature14626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corcoran C, et al. Intracellular and extracellular microRNAs in breast cancer. Clin Chem. 2011;57(1):18–32. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.150730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Logozzi M, et al. High levels of exosomes expressing CD63 and caveolin-1 in plasma of melanoma patients. PLoS One. 2009;4(4):e5219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24**.Melo SA, et al. Glypican-1 identifies cancer exosomes and detects early pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;523(7559):177–82. doi: 10.1038/nature14581. Seminal study identifying especific pancreatic cancer-derived exosomes that can serve as a non-invasive diagnostic and screening tool to detect the disease in early stages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Royo F, et al. Different EV enrichment methods suitable for clinical settings yield different subpopulations of urinary extracellular vesicles from human samples. J Extracell Vesicles. 2016;5:29497. doi: 10.3402/jev.v5.29497. Comparison of different EV isolation methods for clinical application. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skog J, et al. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(12):1470–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Toro J, et al. Emerging roles of exosomes in normal and pathological conditions: new insights for diagnosis and therapeutic applications. Front Immunol. 2015;6:203. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keller S, et al. Body fluid derived exosomes as a novel template for clinical diagnostics. J Transl Med. 2011;9:86. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lasser C. Identification and analysis of circulating exosomal microRNA in human body fluids. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1024:109–28. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-453-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor DD, Gercel-Taylor C. MicroRNA signatures of tumor-derived exosomes as diagnostic biomarkers of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31**.Hoshino A, et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527(7578):329–35. doi: 10.1038/nature15756. Outstanding study showing how exosome cargo can dictate metastasis organotropism and could be used as a prognostic tool for cancer disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahlert C, et al. Identification of double-stranded genomic DNA spanning all chromosomes with mutated KRAS and p53 DNA in the serum exosomes of patients with pancreatic cancer. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(7):3869–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C113.532267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balaj L, et al. Heparin affinity purification of extracellular vesicles. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10266. doi: 10.1038/srep10266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Long JD, et al. A non-invasive miRNA based assay to detect bladder cancer in cell-free urine. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7(11):2500–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tovar-Camargo OA, Toden S, Goel A. Exosomal microRNA Biomarkers: Emerging Frontiers in Colorectal and Other Human Cancers. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2016;16(5):553–67. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2016.1156535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munagala R, Aqil F, Gupta RC. Exosomal miRNAs as biomarkers of recurrent lung cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4939-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohankumar S, Patel T. Extracellular vesicle long noncoding RNA as potential biomarkers of liver cancer. Brief Funct Genomics. 2015 doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elv058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nilsson J, et al. Prostate cancer-derived urine exosomes: a novel approach to biomarkers for prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(10):1603–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thakur BK, et al. Double-stranded DNA in exosomes: a novel biomarker in cancer detection. Cell Res. 2014;24(6):766–9. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lazaro-Ibanez E, et al. Different gDNA content in the subpopulations of prostate cancer extracellular vesicles: apoptotic bodies, microvesicles, and exosomes. Prostate. 2014;74(14):1379–90. doi: 10.1002/pros.22853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balaj L, et al. Tumour microvesicles contain retrotransposon elements and amplified oncogene sequences. Nat Commun. 2011;2:180. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42*.Royo F, et al. Transcriptomic profiling of urine extracellular vesicles reveals alterations of CDH3 in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(6):6835–46. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6899. Identification of urine extracellular vesicle transcripts with differential abundanc in prostate cancer patients and with the potential to inform about molecular alterations of the tumor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Motamedinia P, et al. Urine Exosomes for Non-Invasive Assessment of Gene Expression and Mutations of Prostate Cancer. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0154507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corcoran C, Rani S, O’Driscoll L. miR-34a is an intracellular and exosomal predictive biomarker for response to docetaxel with clinical relevance to prostate cancer progression. Prostate. 2014;74(13):1320–34. doi: 10.1002/pros.22848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palma J, et al. MicroRNAs are exported from malignant cells in customized particles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(18):9125–38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahadi A, et al. Long non-coding RNAs harboring miRNA seed regions are enriched in prostate cancer exosomes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24922. doi: 10.1038/srep24922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aleckovic M, Kang Y. Welcoming Treat: Astrocyte-Derived Exosomes Induce PTEN Suppression to Foster Brain Metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(5):554–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meng X, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic relevance of circulating exosomal miR-373, miR-200a, miR-200b and miR-200c in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50*.Zhang L, et al. Microenvironment-induced PTEN loss by exosomal microRNA primes brain metastasis outgrowth. Nature. 2015;527(7576):100–4. doi: 10.1038/nature15376. Cancer-derived exosomes communicate with and modulate the metastatic niche through the genetic silencing of the tumor suppressor PTEN. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Z, et al. Exosomal microRNA-141 is upregulated in the serum of prostate cancer patients. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:139–48. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S95565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pfeffer SR, et al. Detection of Exosomal miRNAs in the Plasma of Melanoma Patients. J Clin Med. 2015;4(12):2012–27. doi: 10.3390/jcm4121957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rabinowits G, et al. Exosomal microRNA: a diagnostic marker for lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2009;10(1):42–6. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanaka Y, et al. Clinical impact of serum exosomal microRNA-21 as a clinical biomarker in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2013;119(6):1159–67. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang L, et al. Potential role of exosome-associated microRNA panels and in vivo environment to predict drug resistance for patients with multiple myeloma. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Overbye A, et al. Identification of prostate cancer biomarkers in urinary exosomes. Oncotarget. 2015;6(30):30357–76. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wojtuszkiewicz A, et al. Exosomes Secreted by Apoptosis-Resistant Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Blasts Harbor Regulatory Network Proteins Potentially Involved in Antagonism of Apoptosis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15(4):1281–98. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.052944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alix-Panabieres C, Pantel K. Clinical Applications of Circulating Tumor Cells and Circulating Tumor DNA as Liquid Biopsy. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(5):479–91. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thery C, et al. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2006;Chapter 3(Unit 3):22. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb0322s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leberman R. The isolation of plant viruses by means of “simple” coacervates. Virology. 1966;30(3):341–7. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(66)90112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rider MA, Hurwitz SN, Meckes DG., Jr ExtraPEG: A Polyethylene Glycol-Based Method for Enrichment of Extracellular Vesicles. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23978. doi: 10.1038/srep23978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheng L, et al. Exosomes provide a protective and enriched source of miRNA for biomarker profiling compared to intracellular and cell-free blood. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3 doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.23743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Isin M, et al. Exosomal lncRNA-p21 levels may help to distinguish prostate cancer from benign disease. Front Genet. 2015;6:168. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saenz-Cuesta M, et al. Methods for extracellular vesicles isolation in a hospital setting. Front Immunol. 2015;6:50. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abramowicz A, Widlak P, Pietrowska M. Proteomic analysis of exosomal cargo: the challenge of high purity vesicle isolation. Mol Biosyst. 2016;12(5):1407–1419. doi: 10.1039/c6mb00082g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao C, O’Connor PB. Removal of polyethylene glycols from protein samples using titanium dioxide. Anal Biochem. 2007;365(2):283–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheruvanky A, et al. Rapid isolation of urinary exosomal biomarkers using a nanomembrane ultrafiltration concentrator. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292(5):F1657–61. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00434.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lobb RJ, et al. Optimized exosome isolation protocol for cell culture supernatant and human plasma. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:27031. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.27031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boing AN, et al. Single-step isolation of extracellular vesicles by size-exclusion chromatography. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3 doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.23430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Menezes-Neto A, et al. Size-exclusion chromatography as a stand-alone methodology identifies novel markers in mass spectrometry analyses of plasma-derived vesicles from healthy individuals. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:27378. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.27378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Musante L, et al. A simplified method to recover urinary vesicles for clinical applications, and sample banking. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7532. doi: 10.1038/srep07532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mathivanan S, Simpson RJ. ExoCarta: A compendium of exosomal proteins and RNA. Proteomics. 2009;9(21):4997–5000. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Duijvesz D, et al. Exosomes as biomarker treasure chests for prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2011;59(5):823–31. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao Z, et al. A microfluidic ExoSearch chip for multiplexed exosome detection towards blood-based ovarian cancer diagnosis. Lab Chip. 2016;16(3):489–96. doi: 10.1039/c5lc01117e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kanwar SS, et al. Microfluidic device (ExoChip) for on-chip isolation, quantification and characterization of circulating exosomes. Lab Chip. 2014;14(11):1891–900. doi: 10.1039/c4lc00136b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maas SL, et al. Possibilities and limitations of current technologies for quantification of biological extracellular vesicles and synthetic mimics. J Control Release. 2015;200:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nolte-’t Hoen EN, et al. Dynamics of dendritic cell-derived vesicles: high-resolution flow cytometric analysis of extracellular vesicle quantity and quality. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;93(3):395–402. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0911480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Groot Kormelink T, et al. Prerequisites for the analysis and sorting of extracellular vesicle subpopulations by high-resolution flow cytometry. Cytometry A. 2016;89(2):135–47. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Echevarria J, et al. Microarray-based identification of lectins for the purification of human urinary extracellular vesicles directly from urine samples. Chembiochem. 2014;15(11):1621–6. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kittel A, Falus A, Buzas E. Microencapsulation technology by nature: Cell derived extracellular vesicles with therapeutic potential. Eur J Microbiol Immunol (Bp) 2013;3(2):91–6. doi: 10.1556/EuJMI.3.2013.2.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee Y, El Andaloussi S, Wood MJ. Exosomes and microvesicles: extracellular vesicles for genetic information transfer and gene therapy. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(R1):R125–34. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82**.Lener T, et al. Applying extracellular vesicles based therapeutics in clinical trials -an ISEV position paper. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:30087. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.30087. Seminal paper that sets the basis for the therapeutic use of exosomes in the clinic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lamparski HG, et al. Production and characterization of clinical grade exosomes derived from dendritic cells. J Immunol Methods. 2002;270(2):211–26. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.El-Andaloussi S, et al. Exosome-mediated delivery of siRNA in vitro and in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(12):2112–26. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lotvall J, et al. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: a position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3:26913. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.26913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]