Abstract

Temporal lobe epilepsy is the most common form of medically-intractable epilepsy. While seizures in TLE originate in structures such as hippocampus, amygdala, and temporal cortex, they propagate through a crucial relay: the midline/intralaminar thalamus. Prior studies have shown that pharmacological inhibition of midline thalamus attenuates limbic seizures. Here, we examined a recently developed technology, Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs), as a means of chemogenetic silencing to attenuate limbic seizures. Adult, male rats were electrically kindled from the amygdala, and injected with virus coding for inhibitory (hM4Di) DREADDs into the midline/intralaminar thalamus. When treated with the otherwise inert ligand Clozapine-N-Oxide (CNO) at doses of 2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg, electrographic and behavioral seizure manifestations were suppressed in comparison to vehicle. At higher doses, we found complete blockade of seizure activity in a subset of subjects. CNO displayed a sharp time-response profile, with significant seizure attenuation seen 20-30 mins post injection, in comparison to 10 and 40 mins post injection. Seizures in animals injected with a control vector (i.e., no DREADD) were unaffected by CNO administration. These data underscore the crucial role of the midline/intralaminar thalamus in the propagation of seizures, specifically in the amygdala kindling model, and provide validation of chemogenetic silencing of limbic seizures.

Keywords: DREADD, CNO, chemogenetic, kindling, amygdala, seizure, rat

Introduction

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is the most common cause of intractable seizures, with 20-30% of patients failing to achieve seizure freedom with pharmacotherapy alone (Kwan and Brodie, 2000; Semah et al., 1998). While some patients with TLE can be treated surgically (Engel et al., 2003; Engel, 1998), this is not a viable option for all patients, underscoring the need for more targeted therapies for seizure control.

One region that has attracted particular attention for its role in seizure propagation and promise as a seizure control target is the midline thalamus. In patients with, and animal models of TLE, midline and intralaminar nuclei of the thalamus display volumetric alterations, as well as changes in glucose uptake and synaptic function (Bertram et al., 1998; Cassidy and Gale, 1998; Hamani et al., 2005; Handforth and Treiman, 1995a, 1995b; Rajasekaran et al., 2009; Sierra et al., 2011; Szabó et al., 2006). The midline/intralaminar thalamus is a diverse collection of nuclei located between the third ventricle and lateral thalamic nuclei. These higher-order thalamic regions are broadly interconnected with limbic and frontal cortical circuits. Subregions of this portion of the thalamus include the paraventricular, reuniens, anteromedial, paratenial, centromedian, rhomboid, habenula, and mediodorsal nuclei (Groenewegen and Witter, 2004).

The midline thalamus has been examined in both patients and animal models for effects on seizure propagation (Cassidy and Gale, 1998; Fisher et al., 2010; Hirayasu and Wada, 1992a, 1992b; Patel et al., 1988; Sloan et al., 2011; Upton et al., 1987; Velasco et al., 1995). For example, inactivation of the mediodorsal nuclei by microinjection of GABAergic drugs attenuates seizures evoked from the piriform cortex (“Area Tempestas”) (Cassidy and Gale, 1998). Similarly, muscimol or AP-7 infusion in the lateral habenula attenuates seizures evoked by systemic pilocarpine (De Sarro et al., 1992; Patel et al., 1988). Finally, lesions to midline nuclei, including mediodorsal, rhomboid, centromedian and reuniens attenuate kindled seizures in cats (T Hiyoshi and Wada, 1988, 1988).

Clinically, both the centromedian and anterior nuclei of the thalamus have been targeted for deep brain stimulation (DBS) to suppress seizures (Fisher et al., 2010; Kerrigan et al., 2004; Upton et al., 1987; Valentín et al., 2013; Velasco et al., 1995, 1993, 1987). However, a limitation to thalamic DBS are the reports of cognitive side-effects in a subset of patients (Fisher et al., 2010; Hartikainen et al., 2014). DBS is also limited by issues such as current spread and activation of fibers of passage (Yousif and Liu, 2007). Thus, identification of translational strategies for modulating thalamic activity while minimizing cognitive side effects are a high priority.

One such approach may be the chemogenetic method, which employs Designer Receptor Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs). DREADDs are genetically modified muscarinic acetylcholine receptors that are insensitive to acetylcholine and are activated by the otherwise inert compound, clozapine-n-oxide (CNO) (Armbruster et al., 2007); DREADD variants include the Gi-coupled hM4Di, which suppresses neuronal firing when the receptor is activated (Armbruster et al., 2007; Dong et al., 2010). Only one study (Kätzel et al., 2014) has employed chemogenetics for seizure suppression; this study focused on attenuating seizures by inhibiting the site of seizure initiation, which was defined by focal chemoconvulsant application to motor cortex. However, the use of DREADD-mediated seizure control remains unevaluated in sites distal to the site of seizure initiation.

To test the ability of DREADD-mediated silencing of the thalamus to restrain seizures evoked from a distal site, we selected the amygdala kindling model (Goddard, 1967). Amygdala kindling mimics the crucial phenotype of epilepsy: a chronically lowered seizure threshold (Ng et al., 2006). Amygdala kindled seizures evoke the typical behavioral manifestations of temporal lobe epilepsy (i.e., complex partial seizure or limbic motor seizure, in the rat) including behavior arrest, facial automatisms, and clonus (Sato et al., 1990). This model is particularly useful as it offers experimental control over the timing of the seizure, which is ideal for preclinical validation of new approaches for seizure control. Importantly, the amygdala has strong bidirectional connectivity with the thalamus (Zhang and Bertram, 2003), indeed, midline thalamic nuclei are recruited very early in amygdala kindled seizures (Bertram et al., 2001).

Here we sought to evaluate the efficacy of chemogenetic silencing of the midline thalamus at suppressing seizures evoked from a distal site (i.e., the amygdala). We examined time-effect and dose-response properties of CNO administration on both behavioral and electrographic manifestations of amygdala kindled seizures. To determine if chemogenetic silencing of midline thalamus could avoid cognitive impairments, we also examined working memory in a spontaneous alternation task.

Methods

Animals

All experiments were performed on male Sprague Dawley albino rats (280-350g; Harlan Labs, Frederick, MD). A total of 12 rats were used for these experiments; 2 rats failed to kindle and two rats were excluded due to misplaced virus (one in hippocampus, one in the reticular thalamus). The animals were housed in the Georgetown University Division of Comparative Medicine under environmentally controlled conditions (12 hr light/dark cycle, lights on between 6:00 A.M. and 6:00 P.M.; ambient temperature 23°C ± 1°C) with food (Lab Diet, #5001) and water provided ab libitum. All experiments were performed during light phase of the cycle. Experimental procedures were performed in compliance with Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care standards and were approved by the Georgetown University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Surgery

Rats were anesthetized with 2.8 mg/kg, i.p., equithesin (a combination of sodium pentobarbital, chloral hydrate, ethanol, and magnesium sulfate) (Sigma, St Louis, MO) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf, Tujunga, CA). Rats were injected bilaterally with 1.5 uL of adenoassociated virus [rAAV8-hsyn-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry from the UNC Vector Core, Chapel Hill, NC, 7.4×1012 infectious particles per ml]. Virus was delivered using a 30-gauge dental needle connected via tubing to a Hamilton syringe (Sigma Aldrich). Infusions were controlled by a syringe pump (New Era, Farmingdale, NY) set to deliver virus at a rate of 0.2 uL/min. Virus was injected into the midline thalamus [AP -2.3, ML ±0.5, DV -5.8 below dura, skull plane flat] (Paxinos and Watson, 2007). The injection needle was left in place for at least 5 minutes after the completion of infusion to allow for viral diffusion and avoid reflux up the needle track. A twisted pair of stainless steel electrodes (Plastics One) was then implanted into the basolateral amygdala [AP -0.2, ML +4.9, DV -8.0, incisor bar +5mm (Pellegrino and Cushman, 1967)] and fixed to the skull with dental acrylic and stainless steel jeweler's screws. The efficacy of DREADD-mediating silencing of the mediodorsal thalamus has been previously demonstrated, both behaviorally and electrophysiologically (Parnaudeau et al., 2015, 2013), providing increased confidence in this approach.

Drugs

Clozapine-N-Oxide (CNO) (RTI; NIMH Chemical Synthesis Program, Washington, DC) was dissolved at a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL in 5% Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) in normal saline (Sigma-Aldrich). CNO was administered in the following doses: 1, 2.5, 5.0, and 10 mg/kg, i.p.. An equal (matched) volume of vehicle (saline with 5% DMSO) was given for each dose of CNO on a separate test day.

Afterdischarge Threshold (ADT) Determination

After one week of postoperative recovery to allow seizure threshold to normalize (Forcelli et al., 2013), each animal's ADT was determined. ADT was defined as the minimum current intensity to evoke spiking that outlasted stimulation by 10 sec. Kindling stimulation was provided by a Grass Model S88 stimulator (Grass Technologies, Middleton, WI) connected to an A-M Systems constant current stimulus isolator (A-M Systems, Sequim, WA). The stimulation parameters were set to a 1 sec pulse train of 60 Hz monophasic square wave pulses with a 1.0 msec pulse width. ADT determination began with delivery of 10 uA current intensity, which was elevated every 1 min until afterdischarge threshold was determined. Electrographic responses were collected via a kindling preamplifier with a solid-state relay to switch between record and stimulate modes (Pinnacle Technologies, Lawrence, KS). Signals were amplified 500× and then digitized at a 1KHz sampling rate (PowerLab, AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Data were bandpass filtered (0.1Hz to 30Hz) and stored for offline analysis using LabChart Pro software (AD Instruments).

Amygdala Kindling

Each animal was stimulated daily at the determined ADT until five, Racine Stage 5 seizures were observed. Seizures were scored as follows: Stage 1 = facial clonus, Stage 2 = head bobbing, Stage 3 = forelimb clonus, Stage 4 = forelimb clonus + rearing, Stage 5 = forelimb clonus, rearing + loss of balance (Racine, 1972). After animals were fully kindled (average of 19.4 simulations, ranging between 14-24 stimulations; 3 to 4.5 weeks after surgery), a post-kindling ADT was determined (as above) before dosing commenced. This post-surgical interval prior to testing is consistent with our prior experience using AAV-mediated expression under the hSyn promoter in rats (Soper et al., 2016). It is likewise consistent with prior studies using DREADDs for seizure control (Kätzel et al., 2014) in the neocortex and for the manipulation of the mediodorsal thalamus in behavioral studies (Parnaudeau et al., 2015, 2013).

Once animals are fully kindled, seizure responses are highly stable for months after the last stimulation (Goddard et al., 1969). In the present study, all animals displayed stable Stage 5 seizures across four separate vehicle-treated experimental sessions, which were interspersed between each drug-treated sessions.

CNO testing

Doses were administered in the following order: 5, 2.5, 1 and 10 mg/kg, which was held constant across animals. The order of testing was counterbalanced between vehicle and CNO first. A minimum of 24 h elapsed between tests. After CNO administration, rats were placed in an observation cage for 30 minutes and then stimulated at the post-kindling ADT; this interval between drug treatment and testing is consistent with that employed by Kätzel et al for seizure control in neocortex and Parnaudeau et al for cognitive testing after thalamic manipulations (Kätzel et al., 2014; Parnaudeau et al., 2015, 2013). Once tested at all doses, rats were given a fixed dose of 5.0 mg/kg and placed in an observation cage for 10 minutes, 20 minutes and 40 minutes before being stimulated, to determine a time course of drug action.

Control animals

To control for non-specific effects of CNO, we prepared animals with a control (non-DREADD) vector, kindled them as above, and tested them with the highest dose of CNO (10 mg/kg) used in this study. The highest dose was selected as the most rigorous test of possible non-specific effects.

Analysis of electrographic seizure activity in amygdala

EEGs were analyzed by two observers (EW and PAF), one of whom (PAF) was blinded to treatment. There was a high correlation between the two observers (R2=0.77). The data presented in the manuscript are the result of the observations of the blinded observer. Electrographic seizure duration was measured offline from the onset of stimulation to the end of regular spiking/return to baseline EEG rhythm. In addition, the presence or absence of the following electrographic features was recorded: fast ictal pattern, isolated spike-and-wave pattern, polyspike activity, and secondary afterdischarges.

Spontaneous Alternation in the Y-Maze

As a measure of attentional/memory function, we assessed spontaneous alternation in the Y Maze. The Y maze consisted of a center hexagonal arena (Coulbourn Instruments, Whitehall, PA) with two arms of equal length (35 cm) and a shorter start arm (15 cm). During baseline [drug-free] testing, rats were placed in the start arm for 30 seconds. A guillotine door was then opened and the rat was allowed to enter into the center arena and the door was then closed. The animal was allowed to freely explore the Y-maze for 7 min while entries into the arms were recorded by an observer and/or by ANYmaze software (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL). The following two days, animals were given either 5.0 mg/kg CNO or vehicle i.p. and placed in an observation cage for 25 minutes before being placed in start arm to begin the task. CNO and vehicle conditions were counterbalanced and testing was done post-kindling.

Histology

Once testing was complete, rats were deeply anesthetized with equithesin and perfused with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and cryoprotected in a 30% sucrose solution. Brains were sectioned (40 μm) on a Reichert 975C cryostat and stored in -20°C until histochemical processing. Injection sites and viral spread were verified by immunohistochemistry and/or by endogenous florescence of the mCherry reporter. Electrode placement was determined in the same thionin-counterstained sections.

Slides were washed, quenched (10% hydrogen peroxide in methanol) and blocked (3% Normal Goat Serum, 2% Bovine serum albumin, 0.2% non-fat milk, 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate buffered saline). Slides were then incubated for up to 24 hours with primary antibody (1:2500, rabbit anti-dsRED, Clutch, Mountain View, CA) at 4°C and then incubated for 60 min with secondary antibody (1:500 biotinylated goat anti-rabbit, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) at room temperature. Slides were washed and placed in dark with ABC reagents, prepared according to Vectastain protocol. 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) was dissolved in tris buffered saline at a concentration of 0.25 mg/ml. Slides were placed in DAB for 5 min. 7.5 uL of 30% hydrogen peroxide was then added. Slides were removed from mix and washed after about 1.5 min. Slides were rehydrated, counterstained with thionin stain, dehydrated, and left in xylenes before being coverslipped with Cytoseal-60. For endogenous mCherry visualization, slides were washed 3 × 5 min in tris buffered saline followed by counterstaining with DAPI (200 ng/ml in tris buffered saline). Slides were coverslipped with FluoroGel and sealed with clear coat nail polish.

The region of thalamus labeled by mCherry immunohistochemistry was hand-drawn onto planes from the atlas of Paxinos and Watson and digitized using Adobe Photoshop CC 2015 to indicate minimum, maximum and average virus coverage across cases.

Statistical and Data analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad Inc., La Jolla, CA). Seizure scores are non-parametric, and were thus analyzed using Freidman's test with Dunn's multiple comparison test. Seizure scores for time courses were analyzed using the Skillings-Mack test implementation in Stata SE with Bonferroni-Holm's corrected Wilcoxon tests used for post-hoc comparison. Because under baseline conditions, all animals displayed a maximum response, precluding an increase in seizure severity, a one-tailed directional hypothesis was used. Seizure duration was analyzed by Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with Holm-Sidak's multiple comparison test. Spontaneous alternation data were analyzed using a one-sample t-test against chance performance (0.5) and ANOVA to compare across groups. Inter-rater reliability for electrographic seizure duration was measured by linear correlation (Pearson's R). Proportion of traces showing specific electrographic patterns was analyzed using Chi-Squared test. P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

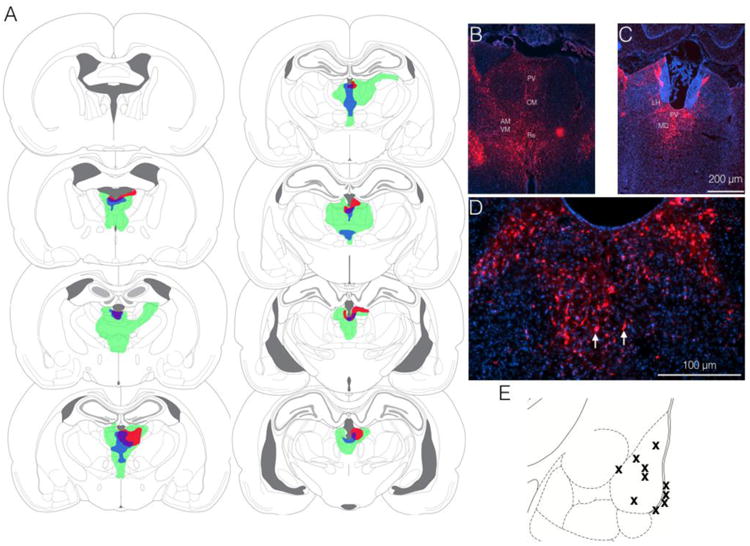

As shown in Figure 1, our virus injections resulted in robust labeling within the midline and intralaminar thalamus. The smallest (red), largest (green) and average (blue) injections are shown. All animals showed labeling within the paraventricular, mediodorsal, and habenular nuclei. 8 of 10 animals also showed labeling in the anteromedian and reuniens nuclei. Labeling was present in the paratenial, rhomboid, and centromedian nuclei in 6, 6, and 7 animals, respectively. Figures 1B and C show photomicrographs of mCherry fluorescence at a more anterior (1B) and posterior (1C) plane from two animals. Figure 1D shows higher magnification of midline thalamus from a third animal, demonstrating individual cell bodies. Fig 1E shows the location of kindling electrode placement in the amygdala; all animals had electrodes placed in or on the border of the basolateral nucleus.

Figure 1. Histological verification of virus infection in midline thalamus.

(A) Smallest (red), largest (green), and average (blue) zone of virus coverage. (B and C) Representative photomicrographs showing mCherry fluorescence within the midline thalamus. PV = paraventricular thalamus, CM = centromedian thalamus, AM = anteromedian thalamus, VM = ventromedial thalamus, Re = reuniens nucleus, MD = mediodorsal thalamus, LH = lateral habenula (D) Higher magnification images showing mCherry positive cell bodies in the midline thalamus. Red = mCherry Blue = DAPI. (E) Histological localization of electrode tips for kindling within the amygdala.

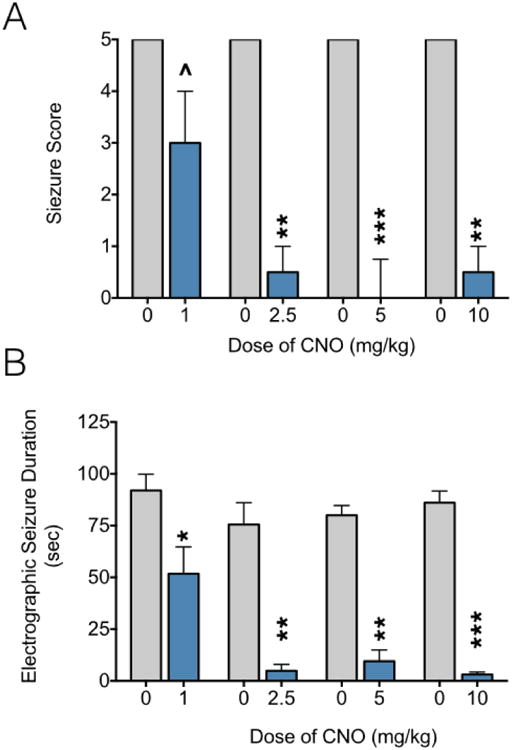

Once animals were fully kindled and at least 27 days after surgery (average of 33 days, ranging between 27-41 days), chemogenetic testing commenced. As shown in Figure 2A, under vehicle treated conditions (4 separate vehicle sessions) all animals displayed score 5 seizures, i.e., rearing with loss of balance. Treatment with CNO significantly suppressed seizure severity (Friedman's Test, P<0.0001). When animals were tested with 1 mg/kg of CNO, the median score was reduced to a 3 (i.e., forelimb clonus). While this dose did not reach the level of statistical significance, there was a trend to (P=0.083, Dunn's test, comparing 1 mg/kg to its respective vehicle). Moreover, 7 of 8 animals displayed a reduction in seizure severity after CNO at this dose, and 2 animals were completely protected. When treated with 2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg of CNO the median seizure severity was 0.5, 0, and 0.5, respectively. This suppression in seizure severity reached the level of statistical significance for each of these doses (P=0.0036, 0.0008, and 0.0036, respectively; Dunn's test comparing each dose to its respective vehicle). When treated with 2.5 or 10 mg/kg of CNO, 4 of 8 animals were completely protected and the maximum seizure severity evoked was a score of 1. When treated with 5 mg/kg of CNO, 6 of 8 animals were completely protected from behavioral seizures (a significant rate of protection, Fisher's Exact Test, P=0.007). Seizure severity did not differ significantly between doses of CNO (all Ps > 0.2).

Figure 2. CNO administration suppresses amygdala kindled seizures in animals infected with M4D DREADD in the midline thalamus.

(A) Seizure severity as a function of CNO dose. Grey bars = vehicle, Blue bars = CNO. Each animal was tested in a repeated measures design with multiple vehicle and CNO doses. ˄ = trend [P=0.086]; ** = significantly lower score compared to respective vehicle, P=0.0036, *** = significantly lower score compared to respective vehicle P=0.008, Dunn's multiple comparison test. Bars indicate median and interquartile range. (B) Electrographic seizure duration as a function of CNO dose. Labeling as in (A); * = significantly less than respective vehicle control, P<0.05; ** P<0.001, *** P<0.0001*, Holm-Sidak's multiple comparison test. Bars indicate mean and standard error.

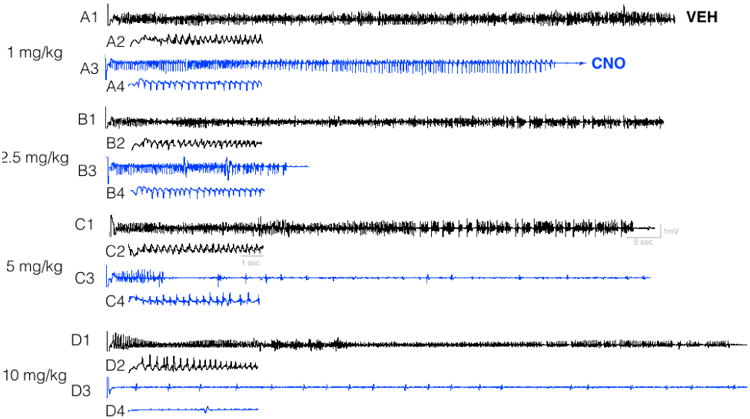

As shown in Figure 2B, electrographic seizure duration was also suppressed by CNO treatment. ANOVA revealed a main effect of treatment (F2.020,14.14=27.28, P<0.0001). This suppression in seizure duration was significant at each dose tested (1 mg/kg, P=0.04; 2.5 mg/kg, P=0.001; 5 mg/kg, P=0.0001; 10 mg/kg, P<0.0001). Averaged across dose for each animal, the mean duration of electrographic seizure activity within the amygdala was 83.4 sec after vehicle treatment, as compared to 17.3 sec with CNO treatment. Seizure duration was significantly shorter in when animals were treated with 2.5, 5, or 10 mg/kg of CNO as compared to 1 mg/kg (Ps=0.036). Representative electrographic traces for each vehicle and dose pair are shown in Figure 3. Each pair of traces for a given dose shows within subject a vehicle (black) and CNO (blue) trace.

Figure 3. Representative electrographic traces recorded from amygdala as a function of CNO administration.

For each dose (1, 2.5, 5 and 10 mg/kg) traces show paired vehicle and CNO recordings from a single subject. Black traces show kindled seizure response with vehicle, blue traces show kindled seizure response with CNO. Inset traces (e.g., A2, A4, B2, B4) show an expanded time scale of the trace shown above starting immediately after the stimulation artifact. Stimulation artifact is seen as the vertical line at the left edge of each trace.

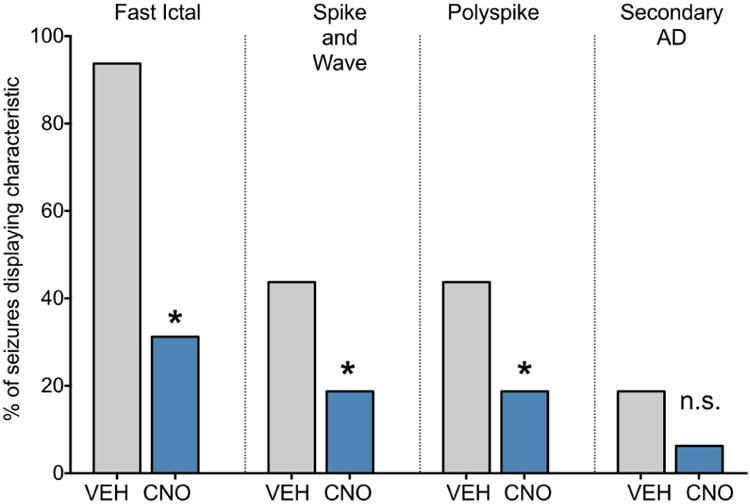

We next quantified the electrographic patterns seen in the amygdala after kindling stimulation. For this analysis, we collapsed across dose to achieve a sufficient number of electrographic records for the vehicle and CNO conditions. As shown in Figure 4, after vehicle treatment, 94% of traces showed fast ictal electrographic activity. This was significantly reduced after CNO treatment, with only 31% of traces displaying this activity (Chi-Squared, P<0.0001). 44% of traces after vehicle treatment also displayed isolated spike-and-wave discharges. The presence of this pattern was also significantly reduced by CNO treatment (19% of traces, Chi-Squared, P=0.03). An identical pattern was found for polyspike activity (44% vs. 19%, Chi-Squared, P=0.03). Secondary afterdischarges occurred infrequently in this study; this pattern of activity was found only in 19% of vehicle traces and 6% of CNO traces. The difference in rate of secondary afterdischarges did not differ significantly between vehicle and CNO treatment, perhaps due to the relatively low prevalence of this activity in vehicle treated animals.

Figure 4. Effect of chemogenetic inhibition of midline thalamus on electrographic seizure manifestations.

Percent of electrographic traces showing fast, high amplitude ictal electrographic activity, spike-and-wave activity, polyspikes, or a secondary afterdischarge. * = P<0.05, Chi squared comparing the proportion of vehicle (collapsed across dose) or CNO (collapsed across dose) test sessions showing the respective pattern. Bars indicate % of the 32 traces showing the electrographic characteristic.

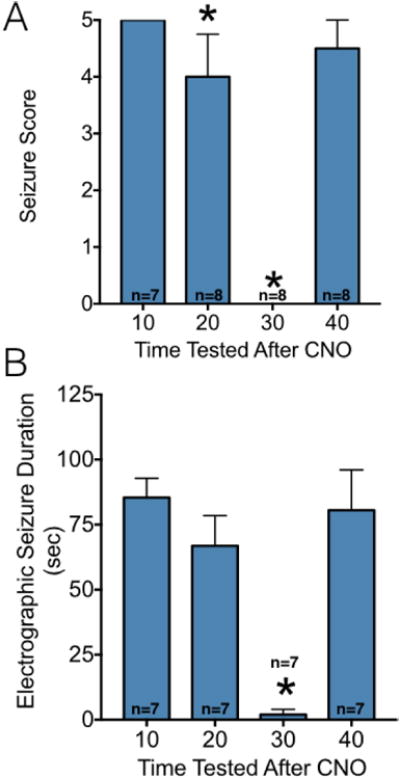

To determine the time-effect profile for CNO, we next treated animals with 5 mg/kg of CNO either 10, 20, 30 or 40 min prior to stimulation. As shown in Figure 5A, we found a very sharp time-response function for CNO in this experiment. With a 10 min delay between treatment and stimulation, the median seizure severity was unchanged from 5 (vehicle, see Fig 2A). With a 20 or 40 min delay between treatment and test, the median seizure score was 4 and 4.5, respectively. With a 30 min delay (which was the timing used in Fig 2) between treatment and stimulation, the seizure severity clearly reduced; with this delay, the median seizure score was 0. Skillings-Mack test revealed a significant difference amongst the groups (P<0.0001), with the suppression in seizure severity with a 20 or 30 min delay reaching the level of significance as compared to the 10 min time (P=0.0312 and 0.0117, respectively). A similar pattern was seen for electrographic seizure duration (Figure 5B) with ANOVA revealing a significant effect of time (F1.507, 6.026=47.02, P=0.0003). The suppression in seizure duration in the 30 min delay condition reached the level of significance as compared to the 10-minute condition (P<0.0001).

Figure 5. Time course of CNO action.

(A) Seizure severity as a function of time after CNO (5 mg/kg) administration. Each animal was tested in a repeated measures design with multiple time points. Bars indicate median and interquartile range. * = significantly lower score compared to the 10-minute time point, P<0.05. (B) Electrographic seizure duration as a function of CNO dose. * = significantly shorter electrographic seizure duration compared to the 10-minute time point, P<0.0001. Bars indicate mean and standard error

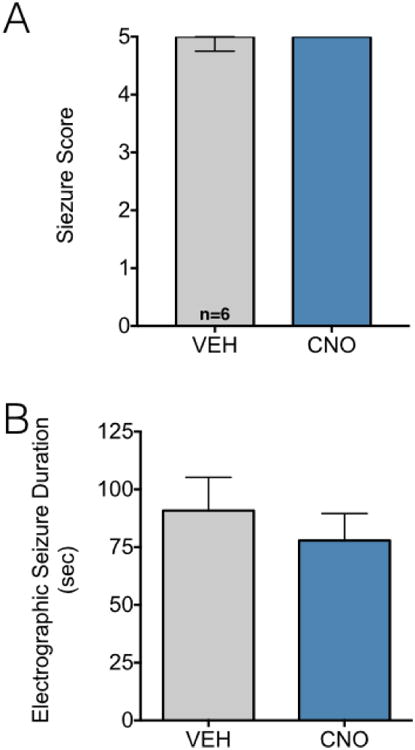

While CNO has been reported to be devoid of action at the endogenous receptorome, we sought to confirm that our effects were not due to a nonspecific action of CNO. As shown in Figure 6, CNO administration to rats with a control vector failed to attenuate either behavioral or electrographic seizures (Ps>0.5, Wilcoxon test and paired t-test, respectively). We chose the highest dose of CNO (10 mg/kg) for this experiment to best test the possibility of non-specific CNO-induced effects.

Figure 6. CNO administration is without effect in animals injected with control virus.

(A) Seizure severity after VEH or CNO (10 mg/kg) administration. Bars indicate median and interquartile range. (B) Electrographic seizure duration after VEH or CNO (10 mg/kg) administration in animals injected with a control (non-DREADD) virus. Bars indicate mean and standard error.

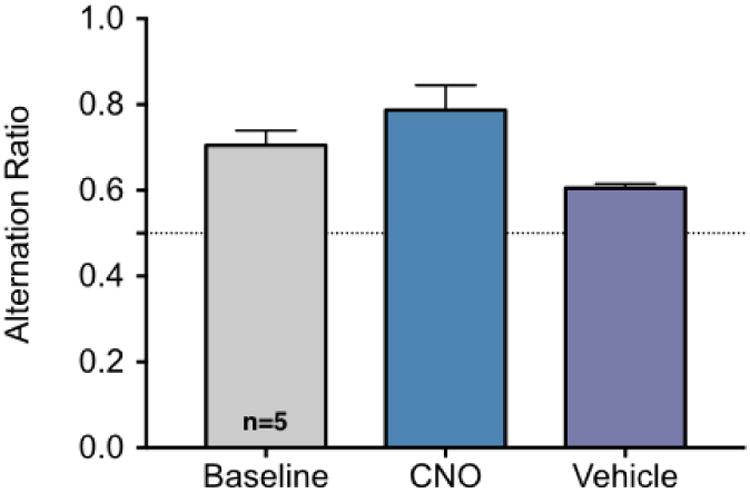

Finally, to determine if inactivation of the midline thalamus would impair working memory, we tested a subset of rats in a spontaneous alternation task (Fig 7). We found that under baseline, vehicle, and CNO-treated conditions, a rate of alternation significantly greater than chance was present. Had chemogenetic inactivation of midline thalamus impaired working memory, we would have expected a chance level of spontaneous alternation. The rate of spontaneous alternation did not differ significantly across treatments (F1.138,4.551=4.372, P=0.09).

Figure 7. Chemogenetic inhibition of the midline thalamus does not impair spontaneous alternation.

Spontaneous alternation in a Y-Maze under baseline, vehicle-treated or CNO (5mg/kg) treated conditions. Each animal was tested under each condition in a balanced design. Dotted line at 0.5 indicates chance level of alternation. * indicates significantly greater alteration than expected by chance (P<0.05, one sample t-test). Treatments did not differ significantly from one another (ANOVA, P>0.05).

Discussion

Here we have shown that chemogenetic inhibition of the midline thalamus attenuates both the electrographic and behavioral manifestations of amygdala-kindled seizures. Suppression in behavioral seizure severity was seen with doses of CNO as low as 2.5 mg/kg, with reductions in electrographic seizure duration evident at doses as low as 1 mg/kg. In animals injected with a control vector, CNO was without effect on seizures. We found a sharp time-response function for CNO in the present experiments, with peak action occurring 30 min after drug treatment. Together, these data provide evidence for chemogenetic targeting of thalamus for seizure control.

Our present findings need to be considered in light of several decades of exploration of the midline thalamus as a target in epilepsy. In rodent models, amygdala or hippocampal-kindled seizures activate midline thalamic nuclei starting with the first kindling stimulations (Bertram et al., 2001). Similarly, there is a strong correlation between the activity patterns in the amygdala and thalamus as well as frontal cortex and thalamus during kindled seizures, with thalamic EEG power increasing as a function seizure severity (Blumenfeld et al., 2007). A series of immediate early gene, 2-deoxyglucose, and fMRI mapping of limbic motor seizures all reveal robust activation of midline thalamic nuclei, further pointing to a pivotal role for thalamus in forebrain seizure activity (Cassidy and Gale, 1998, 1998; DeSalvo et al., 2010; Dunn et al., 2009; Engel et al., 1978; Lanaud et al., 1993; Maggio et al., 1993).

For these reasons it is perhaps not surprising that lesions to the midline thalamus disrupt amygdala kindling (T. Hiyoshi and Wada, 1988; T Hiyoshi and Wada, 1988). Similar results have also been shown across several thalamic nuclei in a variety of forebrain seizure models. Our data are congruent with the existing literature regarding inhibition of thalamic nuclei and their role in limbic seizures. For example, stimulation-induced hyperpolarization of the mediodorsal thalamus suppresses electrographic seizures evoked by kindling of hippocampus or entorhinal cortex (Zhang and Bertram, 2015). Similarly, inhibition of the centromedian nucleus of the thalamus by focal microinjection of the GABA-A receptor agonist, muscimol, inhibited seizures evoked by systemic bicuculline (Miller et al., 1989). Moreover, muscimol microinjection in mediodorsal thalamus (MD) completely prevented seizures evoked from Area Tempestas; a similar profile of protection was found with AMPA receptor antagonist in MD, but not with NMDA receptor antagonist in MD (Cassidy and Gale, 1998). A similar study from Patel and colleagues found infusion of either muscimol or the NMDA receptor antagonist AP7 in either the MD or the lateral habenula protected against seizures evoked by pilocarpine (Patel et al., 1988). Thus, seizure suppressive effects of silencing midline thalamic nuclei have been shown in experimental seizure models across several species, including rat (Bertram et al., 2008; Cassidy and Gale, 1998), guinea pig (Mirski and Ferrendelli, 1986), cat (T. Hiyoshi and Wada, 1988; T Hiyoshi and Wada, 1988; Kusske et al., 1972) and non-human primate (Kusske et al., 1972; Mondragon and Lamarche, 1990) These approaches have been incredibly informative, but with the advent of newer viral-based tools, a new level of specificity may be achievable.

A drawback to the microinjection approach is that drug spreads from the site of infusion; this is particularly a problem in the thalamus because of the abundance of white matter tracts between nuclei. It is well established that injected solutions diffuse preferentially along fiber tracts (Allen et al., 2008; Gambino et al., 2014). Thus, the precision of information regarding the exact location and identity of neurons targeted in microinjection studies is in some respects limited. Viral based approaches, which allow for visualization of the area inactivated, can help to address this issue; for example, in several cases we noted spread of virus dorsolaterally away from the infusion site targeted at MD which appeared to approximate the border of the internal medullary lamina. Further refinement of viral targeting and infusion volumes will allow for selective targeting to sub-nuclei, with the added advantage of direct identification of the critical cell populations due to fluorescent labeling. The DREADD also approach avoids confounds associated with electrical stimulation, such as spreading activation with increasing current intensity, and more importantly spares activation of fibers of passage (Vazey and Aston-Jones, 2013). This latter issue is again, particularly important in the thalamus due to the diversity of tracts and projections. Because the viral-mediated approach we selected allowed for specific, confined and labeled targeting, we are able to conclude that drug spread to distal regions and/or activation of fibers of passage cannot account for seizure suppression from midline thalamic nuclei. This is wholly consistent with decades of microinjection studies.

To assess the impact of our targeting on seizure outcomes, we divided the animals into those that displayed a Score 4 or 5 seizure after treatment with 1 mg/kg CNO (non-responders) and those that displayed either no seizure response or a Score 1 or 2 seizure after 1 mg/kg CNO (responders). We found that non-responders displayed poorer coverage of the anterior mediodorsal nucleus as compared to responders (Supplemental Fig 1). Non-responders by contrast, displayed more extensive labeling in off target regions such as the anteroventral ventrolateral nucleus and the laterodorsal ventrolateral nucleus. Of note, both the smallest case (which had poor expression in MD) and the largest case (which had expression in anteroventral ventrolateral nucleus and the laterodorsal ventrolateral nucleus) were poor responders to 1 mg/kg CNO. With respect to off target effects, we also note that one animal each in the poor responder and high responder to 1 mg/kg CNO groups displayed very sparse labeling in hippocampus and hypothalamus; because this was a rare occurrence and does not appear to co-segregate with the efficacy of our manipulation, we suggest that this off target spread is unlikely to account for any of the effects we describe. Similarly, differences in number of days between surgery and testing is unlikely to have contributed to “responder” or non responder” status. When we performed a median split analysis comparing seizure suppression with 1 mg/kg CNO in the faster (13-16 stimulations) and slower (22-23 stimulations) animals, equivalent seizure responses were found.

Due to the reports of cognitive difficulties after anterior thalamic stimulation for epilepsy control (Fisher et al., 2010; Hartikainen et al., 2014), we also evaluated the effects of chemogenetic silencing on cognitive function in our rats. We found that spontaneous alternation performance (as a measure of working memory (Dudchenko, 2004) was unimpaired by CNO treatment. This differs from the report of Means and colleagues (Means et al., 1974), who found that midline thalamic lesions disrupted spontaneous alternation behavior, but is consistent with a report from Tigner (Tigner, 1974) which failed to find deficits in spontaneous alternation after thalamic lesions. It is worth noting that both of these studies used electrolytic lesions, which unlike the DREADD approach, causes substantial damage to fibers of passage. While we found no effect of inhibition of the midline thalamus in a non-learning context, we did not look at other cognitive tasks to explore other possible effects of inhibiting the midline. For example, pharmacological inactivation of the midline thalamus impaired retrieval of fear memories (Padilla-Coreano et al., 2012). Moreover, a recent study employing selective chemogenetic inhibition of the mediodorsal thalamus in mice found significant impairments in cognitive flexibility in an operant reversal-learning task as well as deficits in delayed-nonmatch to position performance in a T maze (Parnaudeau et al., 2015). Thus, the degree to which anticonvulsant manipulations of the midline thalamus impair cognition merits further exploration.

There has only been one other study using DREADDs as a tool for seizure attenuation. Kätzel and colleagues (Kätzel et al., 2014) found that chemogenetic silencing of a defined neocortical seizure focus (induced by either picrotoxin, pilocarpine, or tetanus toxin in motor cortex of mice) significantly attenuated seizures in each model. There are several key differences between our study and theirs. First, we examined a site (thalamus) distal from that of seizure initiation (amygdala), while they targeted a seizure focus. Unfortunately, in the clinic, seizures may originate from unknown or multiple foci. Thus, while targeting a defined focus may work for some seizures, we chose to examine a central “distributor” within the limbic seizure network to broaden the applicability of our manipulation. Second, the amount of time between viral injection and the start of testing differed between our studies. CNO injections began approximately 3 weeks after surgery in the present experiment, whereas in the Kätzel study, testing commenced 8-20 weeks after viral placement. Despite the relatively large differences in timing, seizure model, and species, we also found efficacy of 1 mg/kg CNO; it is worth noting that at higher doses, we were able to completely abolish both behavioral and electrographic seizure activity in some cases.

The time course of CNO action we report was somewhat surprising, both with respect to the latency to onset of effect and the relatively short window during which seizures were suppressed. Initial absorption and brain penetrance likely account for the delay to onset of action seen in the present study, as a 20 minute delay to peak plasma levels have previously been reported in mouse (Guettier et al., 2009), consistent with the behavioral time-course we report. However, others have reported effects with shorter latency. Likewise, while Wirtschafter and Stratford reported a time course similar to to that which we found (Wirtshafter and Stratford, 2016), others have reported durations of CNO action on the order of hours.

How then, can we reconcile the time course we describe with those seen by others? First, comparing the relative effect of a manipulation across different behaviors and different circuits is complicated by the fact that some behavioral readouts may be more sensitive to perturbation than others. In the present study, we electrically drove seizure activity by stimulation of the amygdala; to suppress a response to such a supraphysiological stimulus may require a greater degree of inhibition than that needed to bias or perturb the function of an otherwise normal circuit. Likewise, at the cellular level, the efficacy of DREADD-mediated silencing (or DREADD-mediated activation) may differ based on the intrinsic physiology (e.g., resting membrane potential, input resistance) of the cells expressing the DREADD.

Second, levels of DREADDs, as a non-native receptor system, may vary substantially as a function of virus used, brain region injected, and promoter activity in a given tissue. Comparing non-native receptor effects across studies (especially when delivered via virus) is thus not an “apples to apples” comparison. Differences in receptor levels may have a profound impact on the apparent dose-response and time course. The pharmacokinetic profile of CNO has been reported to be short; CNO levels fall to half maximal in plasma within 15 min of peak (Guettier et al., 2009). Fast clearance coupled with relatively low receptor levels may produce a delayed onset and/or short lasting effect; conversely, with high receptor expression, both onset and duration may be extended.

Pharmacodynamic response to CNO may also influence time course: desensitization of the M4 muscarinic receptor (which is the receptor from which the M4-DREADD was derived) has been reported in the range of 10-15 min of agonist application in cell lines (Holroyd et al., 1999). The canonical mechanism of G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) desensitization relies on phosphorylation by GPCR-receptor kinases (GRKs) and binding of β-arrestin to the third intracellular loop (Haga et al., 1996; Wu et al., 1997). This region is conserved between muscarinic receptors and DREADDs (Armbruster et al., 2007). Thus, it is likely that DREADDs will undergo similar desensitization to that reported with muscarinic receptors. It has been suggested that DREADD desensitization is unlikely to be a major concern in cases of high expression due to a large receptor reserve (Roth, 2016); under such conditions, low agonist concentration would be needed to achieve a maximal effect. In studies that report long-duration of action effects there may be robust receptor reserve -- while some proportion of the DREADDs may be desensitized, enough remain sensitized to evoke maximal responses. Thus, we suggest that a possible explanation for our shorter duration of action was relatively low expression/receptor reserve.

Amygdala kindling was an ideal model to first examine DREADD effects in thalamus for seizure control. This model not only offers face and construct validity (e.g., it triggers complex-partial seizures, changes in temporal lobe histology, and lasting alterations in excitability) but also allows for tight experimental control over the timing of seizures. Future examination of DREADD effects in a model of spontaneous recurrent seizures is now a high priority. As compared to alternative approaches for selective cell targeting (e.g., optogenetics), DREADDs may offer some advantages, with perhaps the greatest benefit being the lack of chronically implanted hardware and risk of heat-induced damage to tissue. Both approaches may be useful in selective silencing of particular thalamic connections to other critical nodes in seizure circuitry, such as the hippocampus, amygdala, frontal cortex, and rhinal cortex, enabling mechanistic understanding of the thalamic subnetworks through which anticonvulsant effects are generated.

Conclusions

Here we have shown that DREADD-mediated chemogenetic silencing of the midline thalamus is a potent and efficacious method for suppressing limbic seizures. Looking forward, the present study provides a springboard from which we can employ chemogenetic methods to isolate the role of specific nuclei of the midline thalamus, as well as target their projections to other components of the limbic seizure network. These approaches will enhance our understanding of the pathways by which seizures propagate and to identify substrates to target for enhanced seizure control while minimizing side effects. Overall, this study shows the possibilities for the use of DREADDs for inactivating regions for attenuation of seizures distal to the site of seizure initiation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

DREADD-mediated silencing of midline thalamus suppressed kindled seizures

Behavioral and electrographic seizure manifestations were suppressed

CNO was without effect in animals infected with a control virus

Acknowledgments

PAF received support from an Epilepsy Foundation / American Epilepsy Society grant, a grant from the Georgetown University Dean for Research, and KL2TR001432.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen TA, Narayanan NS, Kholodar-Smith DB, Zhao Y, Laubach M, Brown TH. Imaging the spread of reversible brain inactivations using fluorescent muscimol. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;171:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5163–5168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700293104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender D, Holschbach M, Stöcklin G. Synthesis of n.c.a carbon-11 labelled clozapine and its major metabolite clozapine-N-oxide and comparison of their biodistribution in mice. Nucl Med Biol. 1994;21:921–925. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram EH, Mangan PS, Zhang D, Scott CA, Williamson JM. The midline thalamus: alterations and a potential role in limbic epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2001;42:967–978. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.042008967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram EH, Zhang D, Williamson JM. Multiple roles of midline dorsal thalamic nuclei in induction and spread of limbic seizures. Epilepsia. 2008;49:256–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram EH, Zhang DX, Mangan P, Fountain N, Rempe D. Functional anatomy of limbic epilepsy: a proposal for central synchronization of a diffusely hyperexcitable network. Epilepsy Res. 1998;32:194–205. doi: 10.1016/S0920-1211(98)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld H, Rivera M, Vasquez JG, Shah A, Ismail D, Enev M, Zaveri HP. Neocortical and thalamic spread of amygdala kindled seizures. Epilepsia. 2007;48:254–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy RM, Gale K. Mediodorsal thalamus plays a critical role in the development of limbic motor seizures. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 1998;18:9002–9009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-09002.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo MN, Schridde U, Mishra AM, Motelow JE, Purcaro MJ, Danielson N, Bai X, Hyder F, Blumenfeld H. Focal BOLD fMRI changes in bicuculline-induced tonic-clonic seizures in the rat. NeuroImage. 2010;50:902–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sarro G, Meldrum BS, De Sarro A, Patel S. Excitatory neurotransmitters in the lateral habenula and pedunculopontine nucleus of rat modulate limbic seizures induced by pilocarpine. Brain Res. 1992;591:209–222. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91701-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Rogan SC, Roth BL. Directed molecular evolution of DREADDs: a generic approach to creating next-generation RASSLs. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:561–573. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudchenko PA. An overview of the tasks used to test working memory in rodents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:699–709. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JF, Tuor UI, Kmech J, Young NA, Henderson AK, Jackson JC, Valentine PA, Teskey GC. Functional brain mapping at 9.4T using a new MRI-compatible electrode chronically implanted in rats. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:222–228. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J., Jr Etiology as a risk factor for medically refractory epilepsy: a case for early surgical intervention. Neurology. 1998;51:1243–1244. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.5.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J, Wiebe S, French J, Sperling M, Williamson P, Spencer D, Gumnit R, Zahn C, Westbrook E, Enos B Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology, American Epilepsy Society, American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Practice parameter: temporal lobe and localized neocortical resections for epilepsy: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology, in association with the American Epilepsy Society and the American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Neurology. 2003;60:538–547. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055086.35806.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J, Wolfson L, Brown L. Anatomical correlates of electrical and behavioral events related to amygdaloid kindling. Ann Neurol. 1978;3:538–544. doi: 10.1002/ana.410030615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R, Salanova V, Witt T, Worth R, Henry T, Gross R, Oommen K, Osorio I, Nazzaro J, Labar D, Kaplitt M, Sperling M, Sandok E, Neal J, Handforth A, Stern J, DeSalles A, Chung S, Shetter A, Bergen D, Bakay R, Henderson J, French J, Baltuch G, Rosenfeld W, Youkilis A, Marks W, Garcia P, Barbaro N, Fountain N, Bazil C, Goodman R, McKhann G, Babu Krishnamurthy K, Papavassiliou S, Epstein C, Pollard J, Tonder L, Grebin J, Coffey R, Graves N. Electrical stimulation of the anterior nucleus of thalamus for treatment of refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2010;51:899–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forcelli PA, Kalikhman D, Gale K. Delayed effect of craniotomy on experimental seizures in rats. PloS One. 2013;8:e81401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambino F, Pagès S, Kehayas V, Baptista D, Tatti R, Carleton A, Holtmaat A. Sensory-evoked LTP driven by dendritic plateau potentials in vivo. Nature. 2014;515:116–119. doi: 10.1038/nature13664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard GV. Development of epileptic seizures through brain stimulation at low intensity. Nature. 1967;214:1020–1021. doi: 10.1038/2141020a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard GV, McIntyre DC, Leech CK. A permanent change in brain function resulting from daily electrical stimulation. Exp Neurol. 1969;25:295–330. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(69)90128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen HJ, Witter MP. Chapter 17 - Thalamus. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. Third. Academic Press; Burlington: 2004. pp. 407–453. [Google Scholar]

- Guettier JM, Gautam D, Scarselli M, Ruiz de Azua I, Li JH, Rosemond E, Ma X, Gonzalez FJ, Armbruster BN, Lu H, Roth BL, Wess J. A chemical-genetic approach to study G protein regulation of beta cell function in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19197–19202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906593106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga K, Kameyama K, Haga T, Kikkawa U, Shiozaki K, Uchiyama H. Phosphorylation of human m1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors by G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 and protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2776–2782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamani C, Paulo I de, Mello LEaM. Neo-Timm staining in the thalamus of chronically epileptic rats. Braz J Med Biol Res Rev Bras Pesqui Médicas E Biológicas Soc Bras Biofísica Al. 2005;38:1677–1682. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2005001100016. doi:/S0100-879X2005001100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handforth A, Treiman DM. Functional mapping of the early stages of status epilepticus: A 14C-2-deoxyglucose study in the lithium-pilocarpine model in rat. Neuroscience. 1995a;64:1057–1073. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00376-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handforth A, Treiman DM. Functional mapping of the late stages of status epilepticus in the lithium-pilocarpine model in rat: a 14C-2-deoxyglucose study. Neuroscience. 1995b;64:1075–1089. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00377-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartikainen KM, Sun L, Polvivaara M, Brause M, Lehtimäki K, Haapasalo J, Möttönen T, Väyrynen K, Ogawa KH, Öhman J, Peltola J. Immediate effects of deep brain stimulation of anterior thalamic nuclei on executive functions and emotion-attention interaction in humans. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2014;36:540–550. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2014.913554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayasu Y, Wada JA. Convulsive seizures in rats induced by N-methyl-D-aspartate injection into the massa intermedia. Brain Res. 1992a;577:36–40. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90534-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayasu Y, Wada JA. N-methyl-D-aspartate injection into the massa intermedia facilitates development of limbic kindling in rats. Epilepsia. 1992b;33:965–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992.tb01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiyoshi T, Wada JA. Midline thalamic lesion and feline amygdaloid kindling. II. Effect of lesion placement upon completion of primary site kindling. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1988;70:339–349. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(88)90052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiyoshi T, Wada JA. Midline thalamic lesion and feline amygdaloid kindling. I. Effect of lesion placement prior to kindling. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1988;70:325–338. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(88)90051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd EW, Szekeres PG, Whittaker RD, Kelly E, Edwardson JM. Effect of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 on the sensitivity of M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors to agonist-induced internalization and desensitization in NG108-15 cells. J Neurochem. 1999;73:1236–1245. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kätzel D, Nicholson E, Schorge S, Walker MC, Kullmann DM. Chemical-genetic attenuation of focal neocortical seizures. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3847. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan JF, Litt B, Fisher RS, Cranstoun S, French JA, Blum DE, Dichter M, Shetter A, Baltuch G, Jaggi J, Krone S, Brodie M, Rise M, Graves N. Electrical stimulation of the anterior nucleus of the thalamus for the treatment of intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2004;45:346–354. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusske JA, Ojemann GA, Ward AA. Effects of lesions in ventral anterior thalamus on experimental focal epilepsy. Exp Neurol. 1972;34:279–290. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(72)90174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:314–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanaud P, Maggio R, Gale K, Grayson DR. Temporal and spatial patterns of expression of c-fos, zif/268, c-jun and jun-B mRNAs in rat brain following seizures evoked focally from the deep prepiriform cortex. Exp Neurol. 1993;119:20–31. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggio R, Lanaud P, Grayson DR, Gale K. Expression of c-fos mRNA following seizures evoked from an epileptogenic site in the deep prepiriform cortex: regional distribution in brain as shown by in situ hybridization. Exp Neurol. 1993;119:11–19. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means LW, Harrell TH, Mayo ES, Alexander GB. Effects of dorsomedial thalamic lesions on spontaneous alternation, maze, activity and runway performance in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1974;12:973–979. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(74)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JW, Hall CM, Holland KD, Ferrendelli JA. Identification of a median thalamic system regulating seizures and arousal. Epilepsia. 1989;30:493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirski MA, Ferrendelli JA. Anterior thalamic mediation of generalized pentylenetetrazol seizures. Brain Res. 1986;399:212–223. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondragon S, Lamarche M. Suppression of motor seizures after specific thalamotomy in chronic epileptic monkeys. Epilepsy Res. 1990;5:137–145. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(90)90030-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng MSM, Hwang P, Burnham WM. Afterdischarge threshold reduction in the kindling model of epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2006;72:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Coreano N, Do-Monte FH, Quirk GJ. A time-dependent role of midline thalamic nuclei in the retrieval of fear memory. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnaudeau S, O'Neill PK, Bolkan SS, Ward RD, Abbas AI, Roth BL, Balsam PD, Gordon JA, Kellendonk C. Inhibition of Mediodorsal Thalamus Disrupts Thalamofrontal Connectivity and Cognition. Neuron. 2013;77:1151–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnaudeau S, Taylor K, Bolkan SS, Ward RD, Balsam PD, Kellendonk C. Mediodorsal thalamus hypofunction impairs flexible goal-directed behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Millan MH, Meldrum BS. Decrease in excitatory transmission within the lateral habenula and the mediodorsal thalamus protects against limbic seizures in rats. Exp Neurol. 1988;101:63–74. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(88)90065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 6th. Academic Press; London, UK: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino LJ, Cushman AJ. A stereotaxic atlas of the rat brain [by] Louis J Pellegrino [and] Anna J Cushman. Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Racine RJ. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroen Clin Neuro. 1972;32:281–94. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekaran K, Sun C, Bertram EH. Altered pharmacology and GABA-A receptor subunit expression in dorsal midline thalamic neurons in limbic epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33:119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth BL. DREADDs for Neuroscientists. Neuron. 2016;89:683–694. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Racine RJ, McIntyre DC. Kindling: basic mechanisms and clinical validity. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1990;76:459–472. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(90)90099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semah F, Picot MC, Adam C, Broglin D, Arzimanoglou A, Bazin B, Cavalcanti D, Baulac M. Is the underlying cause of epilepsy a major prognostic factor for recurrence? Neurology. 1998;51:1256–1262. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.5.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra A, Laitinen T, Lehtimäki K, Rieppo L, Pitkänen A, Gröhn O. Diffusion tensor MRI with tract-based spatial statistics and histology reveals undiscovered lesioned areas in kainate model of epilepsy in rat. Brain Struct Funct. 2011;216:123–135. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Zhang D, Bertram EH., 3rd Increased GABAergic inhibition in the midline thalamus affects signaling and seizure spread in the hippocampus-prefrontal cortex pathway. Epilepsia. 2011;52:523–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02919.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper C, Wicker E, Kulick CV, N'Gouemo P, Forcelli PA. Optogenetic activation of superior colliculus neurons suppresses seizures originating in diverse brain networks. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;87:102–115. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó CA, Lancaster JL, Lee S, Xiong JH, Cook C, Mayes BN, Fox PT. MR imaging volumetry of subcortical structures and cerebellar hemispheres in temporal lobe epilepsy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:2155–2160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tigner JC. The effects of dorsomedial thalamic lesions on learning, reversal, and alternation behavior in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1974;12:13–17. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(74)90062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton AR, Amin I, Garnett S, Springman M, Nahmias C, Cooper IS. Evoked metabolic responses in the limbic-striate system produced by stimulation of anterior thalamic nucleus in man. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol PACE. 1987;10:217–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1987.tb05952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentín A, García Navarrete E, Chelvarajah R, Torres C, Navas M, Vico L, Torres N, Pastor J, Selway R, Sola RG, Alarcon G. Deep brain stimulation of the centromedian thalamic nucleus for the treatment of generalized and frontal epilepsies. Epilepsia. 2013;54:1823–1833. doi: 10.1111/epi.12352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazey EM, Aston-Jones G. New tricks for old dogmas: Optogenetic and designer receptor insights for Parkinson's disease. Brain Res. 2013;1511:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco F, Velasco M, Ogarrio C, Fanghanel G. Electrical stimulation of the centromedian thalamic nucleus in the treatment of convulsive seizures: a preliminary report. Epilepsia. 1987;28:421–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1987.tb03668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco F, Velasco M, Velasco AL, Jiménez F. Effect of chronic electrical stimulation of the centromedian thalamic nuclei on various intractable seizure patterns: I. Clinical seizures and paroxysmal EEG activity. Epilepsia. 1993;34:1052–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco F, Velasco M, Velasco AL, Jimenez F, Marquez I, Rise M. Electrical stimulation of the centromedian thalamic nucleus in control of seizures: long-term studies. Epilepsia. 1995;36:63–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtshafter D, Stratford TR. Chemogenetic inhibition of cells in the paramedian midbrain tegmentum increases locomotor activity in rats. Brain Res. 2016;1632:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Krupnick JG, Benovic JL, Lanier SM. Interaction of arrestins with intracellular domains of muscarinic and alpha2-adrenergic receptors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17836–17842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousif N, Liu X. Modeling the current distribution across the depth electrode-brain interface in deep brain stimulation. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2007;4:623–631. doi: 10.1586/17434440.4.5.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DX, Bertram EH. Suppressing limbic seizures by stimulating medial dorsal thalamic nucleus: factors for efficacy. Epilepsia. 2015;56:479–488. doi: 10.1111/epi.12916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DX, Bertram EH. Different reactions of control and epileptic rats to administration of APV or muscimol on thalamic or CA3-induced CA1 responses. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:2875–2883. doi: 10.1152/jn.00040.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.