Abstract

Introduction

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) mediates cerebrovascular remodeling in vascular smooth muscle layer of the middle cerebral arteries (MCA) in type-2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats. While metformin, oral glucose lowering agent, prevent/restores vascular remodeling and reduce systemic and local ET-1 levels whether this effect was specific to metformin remained unknown. Our working hypotheses were 1) linagliptin, a DPP-IV inhibitor, can reverse diabetes-mediated cerebrovascular remodeling and this is associated with decreased ET-1, and 2) linagliptin prevents the high glucose induced increase in ET-1 and ET receptors in brain vascular smooth muscle cells (bVSMCs).

Methods

Diabetic and non-diabetic GK rats were treated with linagliptin (4 weeks). MCAs were fixed in buffered 4% paraformaldehyde and used for morphometry. Human bVSMCs incubated in normal glucose (5.5mM)/high glucose (25 mM) conditions were treated with the linagliptin (100nM; 24 hours). ET-1 secretion and ET receptors were measured in media and cell lysate respectively. Immunostaining was performed for ETA and ET-B receptor. ET receptors were also measured in cells treated with ET-1 (100nM) and linagliptin.

Results

Linagliptin treatment regressed vascular remodeling of MCAs in diabetic animals but had no effect on blood glucose. bVSMCs in normal/high glucose condition did not show any significant difference in ET-1 secretion or ET-A and ET-B receptor expression. ET-1 treatment in high glucose condition significantly increased the ET-A receptors and this effect was inhibited by linagliptin.

Conclusions

Linagliptin is effective in reversing established pathological cerebrovascular remodeling associated with diabetes. Attenuation of the ET system could be a pleiotropic effect of linagliptin that provides vascular protection.

Keywords: Diabetes, endothelin, linagliptin, brain vascular smooth muscle cells

Introduction

Diabetes induces a state of chronic inflammation and increases the risk of cerebrovascular diseases (1–4). It is well established that ET-1 contributes to diabetes-mediated vascular dysfunction and remodeling in multiple vascular beds including the cerebrovasculature (5–12). The binding of ET-1 with ET-A receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) promotes vasoconstriction and cell proliferation. The action of ET-B receptor differs with respect to its location; in endothelial cells ET-B receptors exert vasorelaxation to counter balance the response of ET-A receptors, whereas in VSMCs it exerts vasoconstriction similar to that of ET-A receptors (13; 14). Our group reported that either single or combined blockade of ET-A and ET-B receptors prevents cerebrovascular dysfunction and remodeling in the GK model of diabetes (5; 10; 11). Specifically, we showed that there is an increase in ET-B receptors on the VSM layer in our diabetic model (11). More recently we showed that inhibition of ET receptors with bosentan or glycemic control by metformin treatment reverses cerebrovascular remodeling and improves myogenic tone of large cerebral arteries (5; 15). The finding that glycemic control with metformin was also associated with decreased plasma ET-1 level and ET-A levels in the mesenteric resistance vessels suggested an interaction between glycemic control and ET system in diabetes (15). It is also possible that metformin has a direct effect. Recent evidence suggest that DPP-IV inhibitors, a new class of oral glucose lowering agents that is increasingly used in the management of type 2 diabetes (16), also improve endothelial dysfunction and reduce pro-oxidative and pro-inflammatory conditions independent of its glucose lowering effects (17). However, the effect of DPP-IV inhibitors on the ET system remained unknown. Thus, the current study was designed to determine the interaction of linagliptin, a DPP-IV inhibitor, with the ET system in vivo in diabetic GK rats and in vitro in bVSMC culture model. We hypothesized that linagliptin treatment can reverse diabetes-mediated cerebrovascular remodeling and this is associated with decreased ET-1. We further hypothesized that linagliptin prevents the high glucose induced increase in ET-1 secretion and upregulation of ET receptors in bVSMCs.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Drug Treatment

All experiments were performed on male GK (Tampa Colony, Taconic; Hudson, NY) rats. The animals were housed at the Augusta University animal care facility that is approved by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All protocols were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee. Animals were fed standard rat chow and tap water ad libitum, and were maintained at 12 h light/dark cycle. Blood glucose levels were measured bi-weekly from tail vein samples using a commercially available glucometer (Freestyle, Abbott Diabetes Care, Inc; Alameda, CA). Glycosylated hemoglobin values (A1CNow-plus, PTS Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) were used as a measurement of long-term blood glucose levels. Rats were initially placed into two groups: those that did not spontaneously develop hyperglycemia (HA1C% ≤7.0) and those that did develop hyperglycemia (HA1C% ≥7.0) by 14 weeks of age, which is past the age where GK rats have been shown develop hyperglycemia. All of the GK rats were litter controlled and fed the same diet under the same environmental conditions prior to the experimental treatment, and thus the nondiabetic GK rats were used as a genetically matched control for the diabetic GK rats in this study on the effects of glycemic control. At 24 weeks of age, after vascular disease is established in the diabetic group, the treatment with linagliptin was initiated in both control and diabetic rats (166 mg/kg in chow for 4 weeks). Animals were anesthetized by sodium pentobarbital and euthanized via cardiac puncture to isolate middle cerebral artery (MCA).

Vessel Morphometry and Immunohistochemistry

After sacrifice, MCA was isolated and mounted on arteriograph (Living Systems Instrumentations, Burlington, VT). After equilibration, vessels were pressure fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde buffer for morphometry. For morphometric analysis and immunohistochemistry, paraffin embedded 4–6 micron thick vessel cross sections were stained with Masson’s trichrome stain or anti-ET-1 antibody, respectively. Slides were imaged using Axiovert microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY) and wall thickness, lumen space were measured and media to lumen ratio were calculated (5; 11).

In Vitro bVSMCs Study

Human bVSMCs were procured from ScienCell research laboratories (Carlsbad, CA). Cells were grown in commercially available normal glucose (5.5 mM, Cat# 10-014-CM; 1g/L) and high glucose (25 mM, Cat# 10-013-CV; 4.5g/L) DMEM media (Corning, Cellgro, Manassas, VA 20109). Both media used in the current study had similar osmolality of 335±30 mOsm/kg H2O. Cells were incubated in normal glucose (5.5mM) or high glucose (25mM) media for 24 hours with and without DPP-IV inhibitor linagliptin (100nM). Cell media was collected for ET-1 measurement by a commercially available ELISA kit (Biotek, R&D, USA). In a separate set of experiments, cells were challenged with ET-1 (100nM) in normal and high glucose conditions. Cell lysate was prepared for the estimation of ET-A and ET-B receptor by Western blotting. Briefly, equivalent amounts of cell lysates of human BVSMCs (15 μg protein/lane) were loaded onto 10% SDS-PAGE, proteins separated, and proteins transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin followed by incubation for 12 hours at 4°C with appropriate primary antibodies. ET-A (Abcam; cat# ab85163) and ET-B (Alomone labs; cat # AER-002) at 1:1000 dilutions or b-actin at 1:3000 dilutions were used. After washing, membranes were incubated for 1 hour at 20°C with appropriate secondary antibodies (horseradish peroxidase [HRP]-conjugated; dilution 1:3000). Prestained molecular weight markers were run in parallel to identify the molecular weight of proteins of interest. For chemiluminescent detection, the membranes were treated with enhanced chemiluminescent reagent and the signals were monitored on Alpha Imager (Alpha Innotech; (San Leandro, CA). Relative band intensity was determined by densitometry software (Alpha Innotech, ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA) and normalized with b-actin protein. Fluorescent immunostaining for ET-A and ET-B was performed on cells grown on the slides. Slides were imaged on Axiovert 200 microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY).

Data Analysis

Two-way ANOVA (2 × 2 design) was used to assess disease and treatment effects in GK rats and first set of cell culture studies (Control vs diabetes or normal glucose vs high glucose X Linagliptin yes or no). A Bonferroni’s post-test adjustment for multiple comparisons was used for all post-hoc mean comparisons for significant effects from all analyses. For cell culture studies in which exogenous ET-1 was added, one-way ANOVA was used to compare vehicle, ET-1 and ET-1 + linagliptin under normal or high glucose conditions followed by a Tukey’s post-hoc comparison. Data was expressed as Mean ± SEM and p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

MCA Morphology and ET-1 Immunostaining

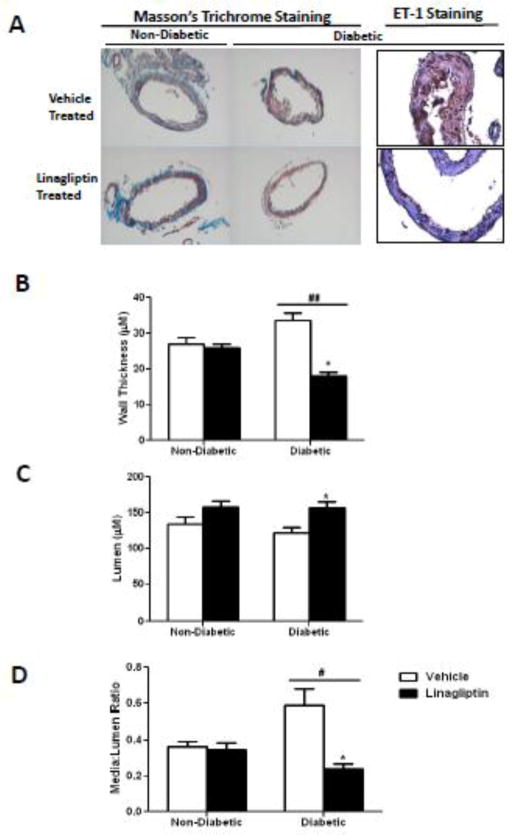

At 28 weeks of age, diabetic animals exhibited increased wall thickness and media to lumen ratio in MCAs (Fig 1B & D). There was a disease and treatment interaction such that these indices were restored in diabetic but not in control animals treated with linagliptin. This effect was independent of blood glucose because linagliptin did not lower blood glucose in diabetic rats (97 ± 3 vs 193 ± 40 mg/dl in control and diabetic animals treated with linagliptin, respectively). There was prominent ET-1 staining in both endothelial and vascular smooth muscle layers in diabetes. Linagliptin-treated diabetic rats showed relatively less staining localized mostly to endothelial layer (Fig 1A)).

Figure 1.

Linagliptin restores cerebrovascular structure in diabetes. A) Representative images of cross sections of MCAs stained by Masson’s trichrome staining or anti-ET-1 antibody. B), C) and D), Measurement of wall thickness, lumen diameter and media to lumen ratio respectively. # p=0.0145; ## p=0.0001 disease and treatment interaction. * p< 0.001 Compared with diabetic vehicle treated group. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM, (n=4).

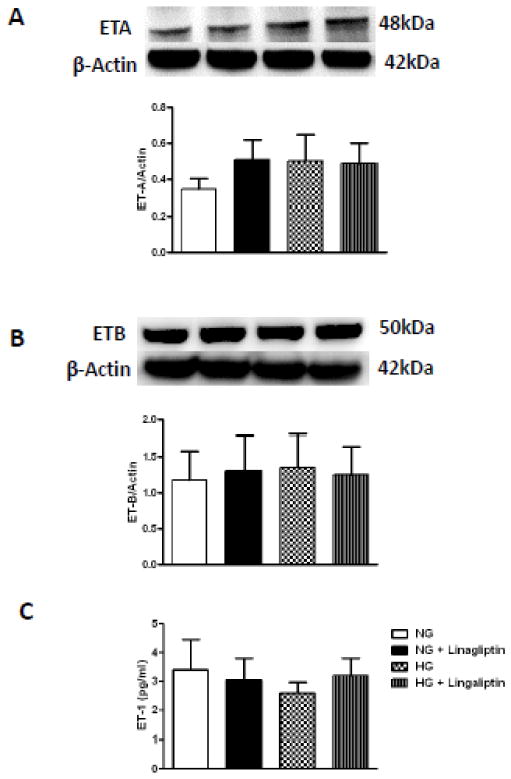

Effect of High Glucose and Linagliptin on bVSMC ET System

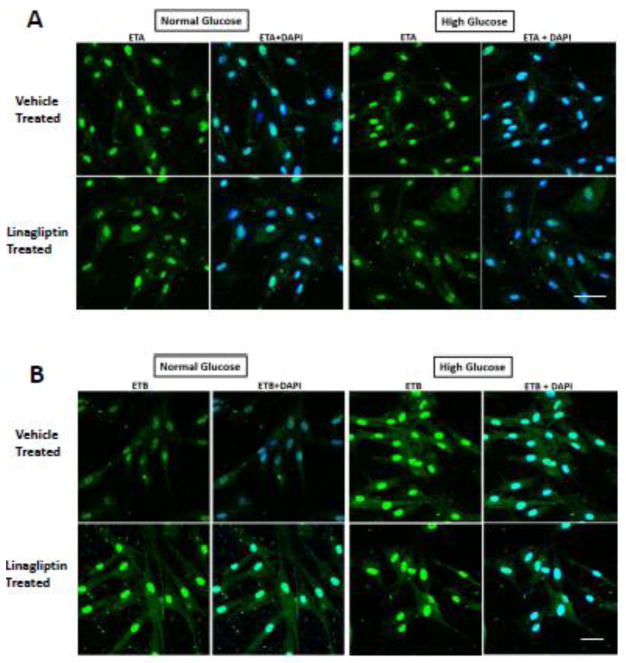

High glucose culture conditions did not impact ET-A receptor levels. Similarly, there was no effect of high glucose and/or linagliptin on ET-B receptors or ET-1 levels (Fig. 2A–C). Immunohistochemical localization studies in intact bVSMCs grown under normal and high glucose conditions yielded similar results. ET-A or ET-B receptor expression in bVSMCs was not different between normal glucose, high glucose and linagliptin treated cells (Fig. 3A and B). However, there was a strong perinuclear staining in all groups.

Figure 2.

High glucose and linagliptin treatment has no effect on endothelin (ET) system of bVSMCs. A) and B) representative immunoblots and analysis of ET-A and ETB receptors respectively in bMVSCs incubated in normal glucose (5mM)/high glucose (25mM) conditions for 24 hours and treated with linagliptin (100nM) did not show any difference in expression of ET-A and ET-B receptors. C) Level of secreted ET-1 in media measured by ELISA was not changed with high glucose and linagliptin treatment. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM, (n=4).

Figure 3.

High glucose and linagliptin treatment has no effect on immunostaining for ETA and ETB receptor in bVSMCs. A) Perinuclear expression of ETA receptor in bMVSCs was observed however, it was not different in normal glucose (5mM)/high glucose (25mM) conditions and linagliptin treatment for 24 hours (Scale bar is 50μm; n=3). B) Perinuclear expression of ETB receptor was observed in normal (5mM) as well as high glucose (25mM) conditions for 24 hours. Linagliptin (100nM) treatment did not change the expression of ET-B receptor (Scale bar is 30μm; n=3).

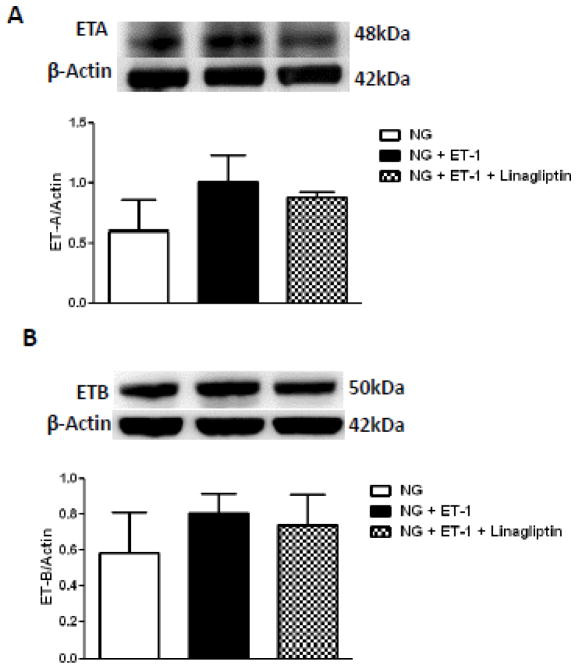

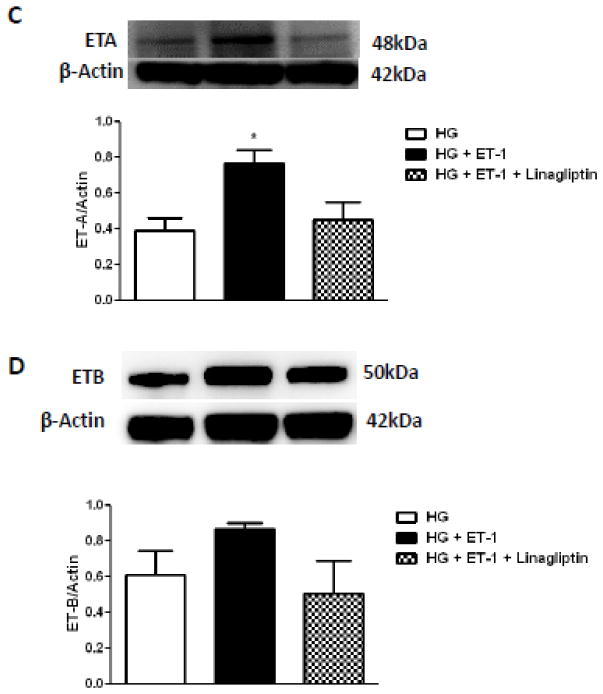

Effect of ET-1 on ET-A and ET-B Receptors in Normal and High Glucose Conditions

Stimulation of bVSMCs with exogenous ET-1 under normal glucose containing medium did not have any effect on ET-A or ET-B receptors (Fig. 4A and B). On the other hand when bVSMCs were challenged with ET-1 in high glucose growth conditions, ET-A, but not ET-B, receptor was significantly increased and this effect was prevented by linagliptin co-treatment (Fig. 4C–D).

Figure 4.

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) upregulates ET-A receptor expression in high glucose condition and this effect is blunted by linagliptin in bVSMCs. A) – D) representative immunoblots and analysis of ET-A and ET-B receptors expression in bVSMCs after incubation with ET-1 for 24 hours in normal/high glucose conditions with or without linagliptin treatment. A) and B) ET-1 (100nM) has no effect on expression of ET-A and ET-B receptors in normal glucose (5mM) condition. Linagliptin treatment also did not change the expression of these receptors. C) ET-1 significantly increased the expression of ET-A receptor in high glucose (5mM) condition (p<0.05; compared with high glucose alone) and linagliptin treatment blunted this effect. D) ET-1 and linagliptin treatment did not change the expression of ET-B receptor in high glucose condition. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM, (n=3).

Discussion

Our previous findings that 1) diabetes-mediated cerebrovascular remodeling is associated with increases in VSM layer ET-B expression, and 2) both glycemic control and ET receptor antagonism prevents/restores this pathological remodeling have led us to the main questions of this study: Can an oral hypoglycemic drug that restores hypertrophic remodeling of the cerebral vasculature regulate the bVSMC ET system and if so, is this effect glucose-dependent? Our results show that treatment of diabetic GK rats with linagliptin after established vascular disease restores MCA structure. This is associated with decreased ET-1 staining in the VSM layer and independent of blood glucose. On the other hand, high glucose growth conditions do not increase ET-1 secretion or ET receptor expression in bVSMCs in our experimental design. Treatment of bVSMCs with ET-1 under high glucose conditions upregulates ET-A receptor levels and this effect is blunted by linagliptin.

Due to its potent proliferative, proinflammatory and profibrotic actions, ET-1 has been implicated to contribute to pathological remodeling of the vasculature in a number of disease states including hypertension and diabetes (1; 18–20). Our group has shown that diabetes mediates hypertrophic remodeling of MCAs (10; 11) and mesenteric resistance vessels (12; 15; 21). As discussed in greater detail below, ET receptor antagonism prevented and reversed this pathological remodeling in a vascular bed specific manner (5; 9–11; 21). Glycemic control achieved by metformin was also able to prevent and reverse vascular remodeling on both vascular beds (15; 22) and decreased plasma and tissue ET-1 levels. Given that glycemic control remains to be a key treatment strategy for the management of vascular complications of diabetes and most patients come to the clinic after onset of these complications, we were interested in testing whether linagliptin, a DPP-IV inhibitor class of oral hypoglycemic that is increasingly used for treatment of diabetes, modulates the ET system after vascular disease is established (16). The results of this study demonstrate that linagliptin partially restores the structure of MCAs while reducing ET-1 levels without any change in blood glucose levels, which led us to further investigate the regulation of ET receptors by linagliptin in an in vitro model.

ET-1 is a potent endogenous vasoconstrictor mainly secreted by endothelial cells however, now it is evident that it can be produced by other cell types also including VSMCs (23–25). Expression of ET-A and ET-B receptors on VSMCs mediates vasoconstriction and proliferation, whereas, ET-B receptors located on endothelial cells mediate vascular relaxation and considered to be vasculoprotective (14; 26). We have shown that ET-A and dual ET-A/ET-B antagonism prevents diabetes-mediated remodeling of the mesenteric vessels that is characterized by augmented collagen deposition and increased wall thickness (21; 27). On the other hand, selective ET-B blockade worsens vascular remodeling, providing support to vasculoprotective effects of this receptor subtype (21). In a follow-up study, we hypothesized that diabetes down regulates vasculoprotective endothelial ET-B receptors in the cerebrovasculature and selective blockade of this receptor subtype would amplify diabetes-mediated MCA remodeling. In contrast to our hypothesis, selective ET-B blockade yielded similar results with selective ET-A or dual receptor antagonism and prevented remodeling (10; 11). This effect was most likely due to upregulation of ET-B receptors on VSMCs. In the current study, ET-1 staining was observed in both endothelial and VSM layers in untreated diabetic animals and linagliptin decreased staining intensity in VSM layer. Thus, we further investigated the changes in the ET system in bVSMC grown under normal and high glucose conditions. Incubation of human bVSMCs with high glucose containing media did not affect ET-1 or ET receptor levels. Interestingly, in high glucose conditions, there was significant perinuclear staining for ET receptors. Avedanian et al.(28) reported similar staining pattern in human aortic endothelial cells and we reported increased perinuclear endothelin converting enzyme staining in endothelial cells grown in high glucose conditions (29). As recently reviewed, nuclear ET receptor localization and signaling has also been reported in cardiac myocytes (30). Linagliptin treatment did not affect ET-1 production or ET receptor expression. While the above observations suggest that high glucose and linagliptin treatment did not alter bVSMCs ET system, we also consider the limitations of the experiments performed. The duration of study (24 hours) and high glucose (25mM) used in the present study may not be sufficient to activate ET system of VSMCs. High glucose stimulates endothelial ET-1 secretion which can then act upon underlying smooth cells. To mimic this possibility, bVSMCs were challenged with ET-1 in normal/high glucose containing media and treated with linagliptin. Interestingly, incubation with ET-1 increased the expression of ET-A receptors in high glucose containing media and linagliptin prevented this effect, suggesting the vasculoprotective effect we observed with linagliptin in diabetic animals may be due to the down regulation of this receptor subtype, which needs to be further pursued in future studies.

Glucose lowering effects of DPP-IV inhibitors are based on the inhibition of degradation of glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) by DPP-IV. However, there is increasing evidence for pleiotropic actions of DPP-IV and DPP-IV inhibitors (31). The vasculoprotective effects of these drugs are not fully understood in part due to the wide range of DPP-IV substrates in addition to GLP-1 and GIP. Examples include neuropeptides, hormones, and meprin-β, which has a role in activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, TGFβ. It is known that ET-1 contributes in inflammatory processes in the vascular wall involving activation of NF-κB and pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1 (32) and these pro-inflammatory cytokines in turn stimulate ET system (33). Thus, the inhibition of pro-inflammatory pathways via DPP-IV inhibition by linagliptin could have contributed to reduction of ET-1 in the vascular wall, which remains to be determined. Further, in diabetic animal model, DPP-IV inhibition increases the bio-availability of GLP-1 for its binding to GLP-1R receptors. In a related study we determined that DPP-IV activity is significantly decreased with our treatment paradigm but we did not measure GLP-1 levels, which can decrease VSMC growth directly (31). This class of agents can also increase eNOS activity in isolated endothelial cells as well as in Zucker obese rats and spontaneously hypertensive rats (34; 35). Salheen and colleagues showed that linagliptin is effective in improving endothelium-dependent relaxation of mesenteric vessels incubated in high glucose as short as two hours due to its antioxidant effects (36). Collectively, these reports suggest that regulation of endothelial eNOS as well as systemic GLP-1 and inflammatory cytokines may have contributed to vasculoprotective effects observed in diabetic rats. However, our finding that linagliptin prevents high glucose-mediated upregulation of ET-A receptors on bVSMC also suggests that linagliptin has independent effects on these cells via a mechanism we do not completely understand.

In conclusion, current study provides novel information that DPP-IV inhibitor linagliptin can reverse cerebrovascular remodeling in diabetic animals. Inhibition of the ET system could be one of the pleiotropic effects exerted by linagliptin that contributes to its vasculoprotective properties. These results suggest that linagliptin treatment can be used as therapeutic strategy in diabetes to prevent vascular complications.

Acknowledgments

Adviye Ergul is a Research Career Scientist at the Charlie Norwood Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Augusta, Georgia. This work was supported in part by VA Merit Award (BX000347), VA Research Career Scientists Award, NIH award (NS070239, R01NS083559) and a research grant from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. to Adviye Ergul; and American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (14POST19580004) to Mohammed Abdelsaid. Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals also provided study material. The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICJME) and were fully responsible for all aspects of the trial and publication development. The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ergul A, Abdelsaid M, Fouda AY, Fagan SC. Cerebral neovascularization in diabetes: implications for stroke recovery and beyond. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:553–563. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ergul A, Kelly-Cobbs A, Abdalla M, Fagan SC. Cerebrovascular complications of diabetes: focus on stroke. Endocr Metab & Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2012;12:148–158. doi: 10.2174/187153012800493477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phipps MS, Jastreboff AM, Furie K, Kernan WN. The diagnosis and management of cerebrovascular disease in diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12:314–323. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0271-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Marco R, Locatelli F, Zoppini G, Verlato G, Bonora E, Muggeo M. Cause-specific mortality in type 2 diabetes. The Verona Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:756–761. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.5.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdelsaid M, Kaczmarek J, Coucha M, Ergul A. Dual endothelin receptor antagonism with bosentan reverses established vascular remodeling and dysfunctional angiogenesis in diabetic rats: relevance to glycemic control. Life Sci. 2014;118:268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan ZA, Chakrabarti S. Endothelins in chronic diabetic complications. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;81:622–634. doi: 10.1139/y03-053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsumoto T, Yoshiyama S, Kobayashi T, Kamata K. Mechanisms underlying enhanced contractile response to endothelin-1 in diabetic rat basilar artery. Peptides. 2004;25:1985–1994. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kohner EM, Patel V, Rassam SM. Role of blood flow and impaired autoregulation in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 1995;44:603–607. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdelsaid M, Ma H, Coucha M, Ergul A. Late dual endothelin receptor blockade with bosentan restores impaired cerebrovascular function in diabetes. Life Sci. 2014;118:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.12.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris AK, Hutchinson JR, Sachidanandam K, Johnson MH, Dorrance AM, Stepp DW, Fagan SC, Ergul A. Type 2 diabetes causes remodeling of cerebrovasculature via differential regulation of matrix metalloproteinases and collagen synthesis: role of endothelin-1. Diabetes. 2005;54:2638–2644. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly-Cobbs AI, Harris AK, Elgebaly MM, Li W, Sachidanandam K, Portik-Dobos V, Johnson M, Ergul A. Endothelial endothelin B receptor-mediated prevention of cerebrovascular remodeling is attenuated in diabetes because of up-regulation of smooth muscle endothelin receptors. J Pharmacol Expe Ther. 2011;337:9–15. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.175380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sachidanandam K, Harris A, Hutchinson J, Ergul A. Microvascular versus macrovascular dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: differences in contractile responses to endothelin-1. Exp Biol Med. 2006;231:1016–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider MP, Boesen EI, Pollock DM. Contrasting actions of endothelin ET(A) and ET(B) receptors in cardiovascular disease. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:731–759. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollock DM. Dissecting the complex physiology of endothelin: new lessons from genetic models. Hypertension. 2010;56:31–33. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.139758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sachidanandam K, Hutchinson JR, Elgebaly MM, Mezzetti EM, Dorrance AM, Motamed K, Ergul A. Glycemic control prevents microvascular remodeling and increased tone in type 2 diabetes: link to endothelin-1. Am J Physiol Regul, Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R952–959. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90537.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guedes EP, Hohl A, de Melo TG, Lauand F. Linagliptin: farmacology, efficacy and safety in type 2 diabetes treatment. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2013;5:25. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-5-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayaori M, Iwakami N, Uto-Kondo H, Sato H, Sasaki M, Komatsu T, Iizuka M, Takiguchi S, Yakushiji E, Nakaya K, Yogo M, Ogura M, Takase B, Murakami T, Ikewaki K. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors attenuate endothelial function as evaluated by flow-mediated vasodilatation in type 2 diabetic patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e003277. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.003277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rautureau Y, Schiffrin EL. Endothelin in hypertension: an update. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21:128–136. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32834f0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ergul A. Endothelin-1 and diabetic complications: focus on the vasculature. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63:477–482. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amiri F, Virdis A, Neves MF, Iglarz M, Seidah NG, Touyz RM, Reudelhuber TL, Schiffrin EL. Endothelium-restricted overexpression of human endothelin-1 causes vascular remodeling and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2004;110:2233–2240. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144462.08345.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sachidanandam K, Portik-Dobos V, Harris AK, Hutchinson JR, Muller E, Johnson MH, Ergul A. Evidence for vasculoprotective effects of ETB receptors in resistance artery remodeling in diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:2753–2758. doi: 10.2337/db07-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly-Cobbs A, Elgebaly MM, Li W, Ergul A. Pressure-independent cerebrovascular remodelling and changes in myogenic reactivity in diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rat in response to glycaemic control. Acta Physiol. 2011;203:245–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubanyi GM, Polokoff MA. Endothelins: molecular biology, biochemistry, pharmacology, physiology, and pathophysiology. Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46:325–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Resink TJ, Hahn AW, Scott-Burden T, Powell J, Weber E, Buhler FR. Inducible endothelin mRNA expression and peptide secretion in cultured human vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;168:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91171-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu JC, Davenport AP. Secretion of endothelin-1 and endothelin-3 by human cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114:551–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu JC, Davenport AP. Regulation of endothelin receptor expression in vascular smooth-muscle cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;26(Suppl 3):S348–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sachidanandam K, Portik-Dobos V, Kelly-Cobbs AI, Ergul A. Dual endothelin receptor antagonism prevents remodeling of resistance arteries in diabetes. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;88:616–621. doi: 10.1139/Y10-034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avedanian L, Riopel J, Bkaily G, Nader M, D’Orleans-Juste P, Jacques D. ETA receptors are present in human aortic vascular endothelial cells and modulate intracellular calcium. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;88:817–829. doi: 10.1139/Y10-057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jafri F, Ergul A. Nuclear localization of endothelin-converting enzyme-1: subisoform specificity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:2192–2196. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000099787.21778.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Branco AF, Bruce GA. G protein-coupled receptor signaling in cardiac nuclear membrane. Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2015;65–2:101–109. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panchapakesan U, Mather A, Pollock C. Role of GLP-1 and DPP-4 in diabetic nephropathy and cardiovascular disease. Clin Sci. 2013;124:17–26. doi: 10.1042/CS20120167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeager ME, Belchenko DD, Nguyen CM, Colvin KL, Ivy DD, Stenmark KR. Endothelin-1, the unfolded protein response, and persistent inflammation: role of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46:14–22. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0506OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Virdis A, Schiffrin EL. Vascular inflammation: a role in vascular disease in hypertension? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2003;12:181–187. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200303000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aroor AR, Sowers JR, Bender SB, Nistala R, Garro M, Mugerfeld I, Hayden MR, Johnson MS, Salam M, Whaley-Connell A, Demarco VG. Dipeptidylpeptidase inhibition is associated with improvement in blood pressure and diastolic function in insulin-resistant male Zucker obese rats. Endocrinology. 2013;154:2501–2513. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah Z, Pineda C, Kampfrath T, Maiseyeu A, Ying Z, Racoma I, Deiuliis J, Xu X, Sun Q, Moffatt-Bruce S, Villamena F, Rajagopalan S. Acute DPP-4 inhibition modulates vascular tone through GLP-1 independent pathways. Vascul Pharmacol. 2011;55:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salheen SM, Panchapakesan U, Pollock CA, Woodman OL. The DPP-4 inhibitor linagliptin and the GLP-1 receptor agonist exendin-4 improve endothelium-dependent relaxation of rat mesenteric arteries in the presence of high glucose. Pharmacol Res. 2015;94:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]