Abstract

Introduction

Individuals with a General Educational Development (GED) degree have the highest smoking prevalence of any education level, including high school dropouts without a GED. Yet little research has been reported providing a context for understanding the exception that the GED represents in the otherwise graded inverse relationship between educational attainment and smoking prevalence. We investigated whether the GED may be associated with a general riskier profile that includes but is not limited to increased smoking prevalence.

Method

Data were obtained from three years (2011-2013) of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health ([NSDUH], N = 55,940]). Prevalence of risky repertoire indicators (e.g., ever arrested, seldom/never wears a seatbelt), indicators of social instability (e.g., frequent relocations), and risky demographic characteristics (e.g., male gender) were compared among high school dropouts, GED holders, and high school graduates using Rao-Scott chi square goodness-of-fit tests and multiple logistic regression.

Results

Those with GEDs differed significantly between both high school dropouts and high school graduates across 19 of 27 (70.4%) risk indicators. Controlling for risky profile characteristics accounted for a significant but limited (25-30%) proportion of the variance in smoking prevalence across these three education levels.

Conclusion

GED holders exhibit a broad high-risk profile of which smoking is just one component. Future research evaluating additional risk indicators and mechanisms that may underpin this generalized risky repertoire are likely needed for a more complete understanding of GED's place in the important relationship between educational attainment and smoking prevalence.

Keywords: cigarette smoking, risky behavior, young adults, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, nationally representative samples, education, General Educational Development (GED)

Introduction

The inverse relationship between educational attainment and the prevalence of cigarette smoking can be observed in many U.S. nationally representative samples (e.g., the National Adult Tobacco Survey [NATS; Agaku et al., 2014; King et al., 2012], National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions [NESARC; Reingle Gonzalez et al., 2016], National Health Interview Survey [NHIS; Jamal et al., 2014], and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health [NSDUH; Garrett et al., 2013]). Recent prevalence estimates derived from the NATS (2014), for example, reveals a graded inverse relationship between educational attainment and smoking prevalence in which prevalence decreases across increasing levels of education (i.e., less than high school: 24.7%; high school graduate: 23.1%; some college: 20.9%; college degree: 9.1%). Interestingly, the General Educational Development (GED) degree is an outlier in this otherwise strikingly graded relationship. Specifically, GED recipients smoke at substantially higher rates (41.9%) than those in all other educational categories, most notably including the category that falls directly below the GED (i.e., high school dropouts without a GED), and the category immediately above (i.e., high school graduates) into which GED holders are sometimes included under the assumption that the two degrees are academically equivalent. While tobacco researchers have undoubtedly noted this exception, to our knowledge, there has been little research reported examining the place of the GED in the relationship between educational attainment and smoking risk, which was the purpose of the present study.

Although a comprehensive characterization of GED recipients is absent from the tobacco literature, tobacco researchers have identified that cigarette smoking is associated with a variety of other problems (e.g., employment and legal issues [Lee et al., 1991; Leino-Arjas et al., 1999; Roll et al., 1996]), thus the high smoking prevalence among GED holders may be a marker of a broader high-risk profile. Reports published outside the tobacco literature support this possibility. For example, economists have noted that GED holders have a higher likelihood of engaging in various deviant or delinquent behaviors (e.g., shoplifting, illegal drug use, being stopped by police [Leino-Arjas et al., 1999]) relative to both high school dropouts and high school graduates. These data may suggest the presence of a generally high-risk profile that is more common among GED holders than high school dropouts without a GED or high school graduates.

The strikingly high smoking prevalence among those with GEDs, combined with the observations made by economists, suggests that it may be worthwhile to investigate whether the increased smoking prevalence among GED holders generalizes to a broader array of risk-related characteristics. We used the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) to examine this question because it is a nationally representative survey that assesses cigarette smoking along with other risk behaviors and socio-demographic characteristics. Thus the primary purpose of this report was to examine whether the disproportionately high smoking prevalence among GED holders compared to high school dropouts without a GED and high school graduates is also observed across other characteristics indicative of a generally high-risk profile. We also examined the degree to which these other risky characteristics might account for the increased smoking prevalence among GED holders or are instead themselves in similar need of explanation.

Method

Data Source

Data were obtained from the three most recent years (2011-2013) of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) at the time this study was initiated (N =168,825; SAMSHA, 2011-2013). The NSDUH is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of the U.S. non-institutionalized population that is conducted each year to assess the prevalence and correlates of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug use. In addition to substance use, the survey also includes questions about risk behaviors other than drug use (e.g., ever arrested, on probation or parole) as well as indicators of social instability that may influence the likelihood of engaging in risk behaviors (e.g., frequent relocations, religious involvement), thus it was appropriate for our current purposes. Collapsing data across the 2011-2013 survey administrations permitted us to conduct our analyses among a larger number of GED holders (i.e., approximately 1% or 500 individuals per year report holding a GED).

Data from all civilian non-institutionalized respondents, including those in group homes, shelters, and college dormitories, were included. Respondents on active military duty, in drug treatment programs, jail or homeless were excluded. The weighted interview response rates were 74.4%, 73.0% and 71.7% in 2011, 2012 and 2013, respectively. A detailed description of the survey procedures is provided by SAMHSA (2013).

The survey includes individuals aged 12 years and older but the current sample was comprised of adults aged 18-25 years (N = 55,940), as only individuals ≤ 25 years old are asked whether they have a GED and only individuals ≥ 18 years are included in the other educational categories. Thus restricting the age range to 18-25 years was necessary to hold age constant across level of educational attainment. Although it is conceivable that some individuals aged 18-25 years have not yet had the opportunity to achieve their highest level of educational attainment, we focus primarily on comparisons between GED holders and the categories directly below (< high school) and above them (high school graduates) in the present report. Whether individuals will receive a high school diploma is typically determined by age 18. Moreover, the use of a young adult sample is consistent with prior research in this area (Johnson and Novak, 2009; Kenkel et al., 2006). Using young adults may also increase the likelihood of observing differences in risky profile indicators associated with educational attainment as engagement in risk behaviors is more common among young adults relative to middle-aged or older adults (SAMHSA, 2013; Ulmer & Steffensmeier, 2014).

Statistical Methods

Sample adjusted frequencies were generated across all respondents between the ages of 18 and 25 years, as well as by education and by current smoking status. Prior to examining the prevalence of risky profile indicators across categories of educational attainment, we verified that the exception that GED recipients typically pose to the inverse relationship between educational attainment and smoking prevalence was discernible in the present sample. More specifically, we determined the prevalence of current smoking across the five educational categories of high school dropouts, GED, high school graduate, some college, and college graduate. For the purposes of presenting a more comprehensive picture of associations between smoking prevalence and educational attainment, we also determined the prevalence of never and former smoking across these categories. “Current smoker” was defined as smoking at least 100 lifetime cigarettes plus past month smoking. “Never smoker” was defined as smoking less than 100 lifetime cigarettes with no past month smoking. “Former smoker” was defined by smoking at least 100 lifetime cigarettes with no past month smoking. Because the substantially higher smoking prevalence among GED holders permits a greater proportion of these respondents with opportunities to quit smoking, thereby potentially inflating estimates of former smoking prevalence artificially, we determined the proportion of former quitters in each educational category from the pool of respondents who had smoked at least 100 lifetime cigarettes as opposed to all respondents in that category. Tests of equal proportions by education level were conducted using Rao-Scott chi-square goodness-of-fit tests to evaluate whether the prevalence of current, never, and former smoking differed across educational categories, with variances estimated using Taylor series linearization.

A modified Delphi method was used to select outcomes indicative of a general high-risk profile (Dalkey and Helmer, 1963). More specifically, three authors (AK, EK, IZ) independently reviewed all items in the NSDUH database and selected (a) both criminal and non-criminal risky or deviant behaviors, where risk could be either to oneself (e.g., not wearing a seatbelt) or others (e.g., attacking someone); (b) outcomes pertaining to the domains of drug use, health, or crime that indicated previous engagement in risky behavior (e.g., past year alcohol abuse/dependence, having an STD, and being arrested, respectively); and (c) characteristics of one's social environment that may modulate the likelihood of engaging in risk behaviors (e.g., religiosity [McCullough and Willoughby, 2009; Walker et al., 2007]). Items that authors unanimously agreed reflected one of these three criteria were automatically selected for inclusion. Items for which there were discrepancies were discussed until a resolution was reached.

The final set of high-risk profile indicators was compared across high school dropouts, GED holders, and high school graduates (N = 29,379). Those who completed some college or graduated college were excluded from this analysis. We focus on comparisons between dropouts, GED holders, and high school graduates because doing so is sufficient to observe deviations from an otherwise orderly graded relationship between education and the outcome of interest that would support the presence of a general high-risk profile among GED holders. We looked for patterns where prevalence of risk indicators were significantly higher among those with GEDs compared to high school dropouts and high school graduates, or where prevalence of protective factors were significantly lower among those with GEDs compared to the other two groups. Tests of equal proportions by education level were conducted using Rao-Scott chi-square goodness-of-fit tests to evaluate differences in the prevalence of risk indicators across educational level, with variances estimated using Taylor series linearization.

Logistic regression was used to investigate the degree to which these other risk indicators accounted for differences in smoking prevalence across the three education levels of high school dropout, GED holder, and high school graduate. This was done in two steps. First, we used univariate logistic regression to investigate associations with smoking status across all risk indicators on which there were significant differences between the three education levels. Second, any indicators that were significantly associated with smoking status were included in a multiple logistic regression model to determine whether the three education levels still differed significantly after controlling for the influence of these additional indicators. Odds ratios (95% CIs) were estimated for both the univariate and multiple logistic regression analyses and the sensitivity/specificity of the final model was evaluated by examining the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. With respect to the multiple logistic regression analysis, unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) represent the odds of smoking for a particular risk indicator (e.g., being male) without controlling for other risk indicators (e.g., race, past year probation, past year alcohol abuse or dependence). Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) represent the odds of smoking for a particular risk indicator adjusting for all other risk indicators in the model. Importantly, given our interest in whether the presence of a riskier profile among GED holders accounts for some of the variance in smoking prevalence in this group relative to high school dropouts and graduates, we focus specifically on changes in the odds of smoking among GED holders versus these other two educational levels before and after adjusting for other risk indicators.

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and statistical significance across all tests was defined as p < .05 (2-tailed).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Participant characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Approximately half of the respondents were between 18-21 years old and the others between 22-25 years old. A majority of the respondents were White, with slightly over two-thirds of the sample having completed either high school (33.6%) or some college (35.1%), slightly less than one third having either dropped out of high school (14.3%) or graduated college (14.6%), and the remaining 2.3% were GED recipients.

Table 1.

Percentage of adults aged 18-25 years with select demographic characteristics — National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), United States, 2011–2013

| % of Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 55,940) | |||

| Weighted % | (95% CI) | N | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 50.1 | (49.6-50.7) | 26,741 |

| Female | 49.9 | (49.3-50.4) | 29,199 |

| Age Group (years) | |||

| 18 | 13.6 | (13.1-14.1) | 7,491 |

| 19 | 12.3 | (11.9-12.8) | 6,692 |

| 20 | 12.5 | (12.1-12.9) | 6,938 |

| 21 | 12.6 | (12.2-13.0) | 7,022 |

| 22-23 | 25.0 | (24.5-25.6) | 14,061 |

| 24-25 | 24.0 | (23.5-24.5) | 13,776 |

| Race/Ethnicitya | |||

| White | 56.6 | (55.9-57.3) | 32,300 |

| Black | 14.1 | (13.5-14.7) | 7,818 |

| Hispanic | 20.7 | (19.9-21.4) | 10,237 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.7 | (0.6-0.8) | 866 |

| Asian | 5.4 | (4.9-5.9) | 2,339 |

| Other | 2.6 | (2.4-2.8) | 2,380 |

| Education Level | |||

| < High school | 14.3 | (13.8-14.7) | 8,372 |

| GED | 2.3 | (2.2-2.5) | 1,496 |

| High school graduate | 33.6 | (32.9-34.4) | 19,511 |

| Some college | 35.1 | (34.4-35.9) | 18,896 |

| College graduate | 14.6 | (14.0-15.2) | 7,665 |

Notes. CI = confidence interval.

The five racial categories (White, Black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Other) are mutually exclusive and exclude Hispanic ethnicity. “Other” includes Native Hawaiians or Other Pacific Islanders and persons of two or more races. Persons identified as Hispanic may be of any race.

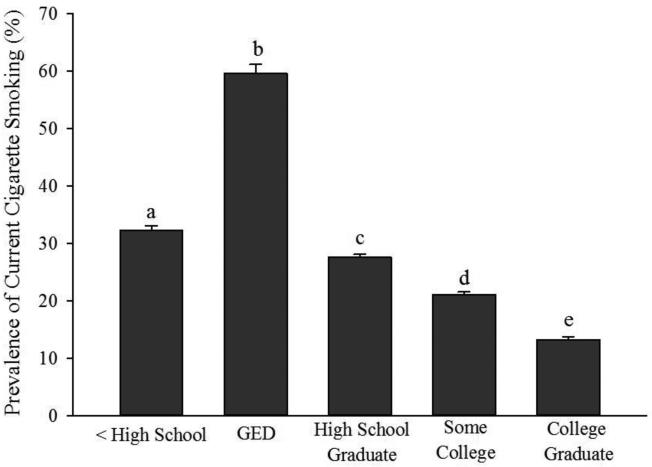

Prevalence of Current Smoking

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of current cigarette smoking across all five levels of educational attainment. Smoking prevalence among GED holders was approximately 60%, which was almost two-fold higher than the 32.3% prevalence among high school dropouts (OR =3.10, 95% CI = 2.67-3.58), and 2.2-fold higher than the 27.6% prevalence among high school graduates (OR = 3.86, 95% CI = 3.33-4.48). Smoking prevalence among GED holders was also significantly higher than the 21.1% prevalence among individuals who completed some college (OR = 5.49, 95% CI = 4.76-6.73), and was nearly five-fold higher than the 13.2% prevalence among college graduates (OR = 9.71, 95% CI = 8.20-11.49).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of current cigarette smoking across levels of educational attainment among U.S. adults aged 18-25 years. Bars represent weighted prevalence estimates and error represents standard error (SE) estimates—National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 2011-2013. Where superscripts differ, Rao Scott chi-square goodness-of-fit tests indicated significant differences, p < .05.

Worth noting is that prevalence of never smoking represents the reverse of the pattern for current smoking, with prevalence among GED holders at 27.1%, which was significantly lower than the prevalence among high school dropouts (55.8%), high school graduates (60%), as well as those who completed some college (66.7%) or graduated college (14.6%) (all ps < .001). In contrast, the pattern of former smoking prevalence was not the reverse of that for current smoking; 11.5% of GED holders who were previous smokers had quit at the time they completed the survey, which did not differ significantly from the 11.9% of high school dropouts who had quit smoking, although the prevalence of quitting in both groups was significantly lower than the 15.1% of high school graduates who quit. All three educational groups had significantly fewer quitters relative to the some college (18.3%) or college graduate groups (27.9% [all ps < .01]).

Prevalence of Other Risk Indicators

Recall that our primary purpose was to examine whether the high smoking prevalence among GED holders relative to high school dropouts and high school graduates generalized across other characteristics indicative of a riskier profile; thus respondents who completed some college or graduated college were excluded from this analysis and the subsequent logistic regression analysis. The prevalence of risk indicators other than cigarette smoking are presented in Table 2. In total, those with GEDs differed significantly from high school dropouts and graduates across 19 of 27 (70.4%) indicators in a manner consistent with the presence of a general high-risk profile among GED holders. Fourteen of these 19 (73.7%) indicators took the form of inverted U-shaped functions where prevalence of risk indicators were significantly higher among those with GEDs relative to the other two education levels as is seen for smoking prevalence. These outcomes included male gender, past year mental illness, being White, past year drug abuse/dependence, past year alcohol abuse/dependence, past year parole or supervised release, past year probation, selling illegal drugs, being arrested for breaking the law, seldom or never wearing a seatbelt as either a passenger or a driver, lifetime STD's, being approached by someone selling drugs, and relocating more than once per year during the past five years. The remaining five (26.3%) indicators took the form of U-shaped functions where prevalence of factors that may be expected to be protective were significantly lower among those with GEDs relative to the other two educational levels. These outcomes included often attending religious services, endorsing the importance of religious beliefs, endorsing that religious beliefs influence one's decisions, and belonging to the two racial/ethnic groups that confer a low risk specifically for cigarette smoking (i.e., being Asian or Hispanic [Agaku et al., 2014; Jamal et al., 2014; King et al., 2012]).

Table 2.

Prevalence of demographic characteristics, risky profile indicators, and indicators of social instability among U.S. adults aged 18-25 years. Data are from the 2011-2013 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

| < HS N = 8,372 | GED N = 1,496 | HS Grad N = 19,511 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) |

| Male* | 56.5 (.7)a | 61.2 (1.7)b | 53.2 (.6)c |

| Past year mental illness* | 17.9 (.6)a | 23.4 (1.6)b | 18.4 (.4)a |

| Race d | |||

| White* | 46.4 (.8)a | 58.7 (1.7)b | 52.0 (.6)c |

| Black | 16.5 (.6)a | 16.2 (1.2)b | 17.1 (.5)a,b |

| Hispanic* | 31.2 (.8)a | 19.4 (1.5)b | 24.1 (.5)c |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.2 (.2)a | 1.3 (.3)a,b | .8 (.1)b |

| Asian* | 2.3 (.3)a | 1.2 (.5)b | 3.3 (.3)c |

| Other | 2.4 (.2)a | 3.3 (.6)a | 2.9 (.2)a |

| Below poverty linee | 40.4 (.9)a | 36.5 (1.6)b | 27.2 (.5)c |

| Risky Profile Indicators | |||

| Past year drug abuse/dependencef* | 9.9 (.4)a | 14.9 (1.3)b | 8.1 (.3)c |

| Past year alcohol abuse/dependencef* | 11.5 (.6)a | 15.9 (1.3)b | 12.0 (.3)a |

| Past year parole/supervised release* | 2.4 (.2)a | 3.8 (.7)b | 1.4 (.1)c |

| Past year on probation* | 8.3 (.4)a | 12.2 (1.2)b | 5.2 (.3)c |

| Sold illegal drugs* | 6.9 (.5)a | 10.4 (1.1)b | 5.7 (.2)c |

| Arrested/booked for breaking the law* | 24.3 (.7)a | 39.1 (1.9)b | 18.5 (.4)c |

| Seldom/never wears seatbelt as passenger* | 12.0 (.5)a | 14.9 (1.2)b | 10.1 (.2)c |

| Seldom/never wears seatbelt as driver* | 9.1 (.5)a | 12.8 (1.1)b | 9.0 (.3)a |

| Lifetime STD* | 3.4 (.2)a | 5.5 (.8)b | 3.5 (.2)a |

| Overweight/Obeseg | 47.9 (1.2)a | 51.2 (3.2)a | 47.9 (.7)a |

| Stole/tried to steal item > $50.00 | 4.3 (.3)a | 5.1 (.8)a | 3.1 (.2)b |

| Attacked someone with intent to harm | 6.3 (.4)a | 7.1 (.8)a | 4.6 (.4)b |

| Drove under the influence of alcohol/drugs | 11.5 (.6)a | 19.5 (1.3)b | 17.6 (.4)b |

| Indicators of Social Instability | |||

| Approached by someone selling drugs* | 22.0 (.7)a | 27.8 (1.6)b | 19.6 (.4)c |

| Moved ≥ once per year (past 5 years)* | 8.9 (.4)a | 15.9 (1.5)b | 8.0 (.2)a |

| “Religious beliefs are important to me”* | 66.6 (.8)a | 60.2 (1.8)b | 66.2 (.4)a |

| “Religious beliefs influence my decisions”* | 58.5 (.8)a | 54.0 (1.9)b | 58.3 (.5)a |

| Often attends religious services* | 16.5 (.6)a | 8.2 (.1)b | 18.1 (.44)c |

Notes. % = percentage of individuals within an educational category who endorsed an item; SE = standard error

indicates deviations from a graded inverse relationship (U-shaped or inverted U-shaped functions). Outcomes for which prevalence estimates did not differ by educational category are indicated with common superscript letters.

The five racial categories (White, Black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Other) are mutually exclusive and exclude Hispanic ethnicity. “Other” includes Native Hawaiians or Other Pacific Islanders and persons of two or more races. Persons identified as Hispanic might be of any race.

Based on reported family income and poverty thresholds published by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Drug and alcohol abuse and dependence criteria used in the NSDUH were defined based upon the criteria listed in the DSM-IV. Illicit substances included marijuana, hallucinogens, heroin, inhalants, tranquilizers, cocaine, pain relievers, stimulants, and sedatives.

Calculated as respondent's weight (kg) / height (m)2. Includes 2013 respondents only.

Multiple Logistic Regression Modeling

The odds of smoking among GED holders relative to high school dropouts and graduates were attenuated by 25-30% when controlling for these risk indicators in multiple logistic regression analyses (Table 3). That is, comparing the odds of smoking among GED holders versus high school dropouts in the unadjusted model (left) to the adjusted model (right) shows that adjusting for a high-risk profile reduced the odds of smoking from being 3.10 times higher among GED holders versus high school dropouts to 2.33, a 24.8% decrease, although with some overlap in confidence intervals between the unadjusted and adjusted models. The odds of smoking among GED holders versus high school graduates decreased from being 3.86 times higher to 2.63 times higher, a 31.9% decrease, and with non-overlapping confidence intervals in the unadjusted and adjusted models. This latter finding suggests that the profile of risk indicators examined in this report account for a significant but nevertheless limited portion of the variance in smoking prevalence among GED holders relative to high school graduates.

Table 3.

Univariate and multiple logistic regressions of demographic characteristics, risky profile indicators, and indicators of social instability predicting current cigarette smokinga among US adults aged 18-25 years. Data are from the 2011-2013 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

| Cigarette Use | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | Unadjusted 95% CI | p | AOR | Adjusted 95% CI | p |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Education | < .0001 | < .0001 | ||||

| GED vs < High School | 3.10 | (2.67, 3.58) | 2.33 | (1.92, 2.82) | ||

| GED vs High School Graduate | 3.86 | (3.33, 4.48) | 2.63 | (2.22, 3.23) | ||

| Male vs Female | 1.58 | (1.49, 1.69) | < .0001 | 1.15 | (1.07, 1.23) | 0.0002 |

| Past yr mental illness vs no mental illnessb | 1.66 | (1.57, 1.76) | <.0001 | 1.21 | (1.13, 1.30) | <.0001 |

| Race/Ethnicityc | < .0001 | < .0001 | ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native vs White | 1.60 | (1.18, 2.16) | 1.03 | (0.72, 1.46) | ||

| Asian vs White | 0.33 | (0.27, 0.40) | 0.61 | (0.49, 0.75) | ||

| Black vs White | 0.49 | (0.45, 0.53) | 0.40 | (0.36, 0.45) | ||

| Hispanic vs White | 0.46 | (0.42, 0.50) | 0.39 | (0.35, 0.43) | ||

| Other vs White | 0.93 | (0.81, 1.07) | 0.77 | (0.65, 0.91) | ||

| Below vs above poverty lined | 1.12 | (1.07, 1.18) | < .0001 | 1.08 | (1.01, 1.15) | 0.0252 |

| Risky Profile Indicators | ||||||

| Past year drug abuse/dep vs no past year drug abuse/depe | 4.88 | (4.51, 5.29) | <.0001 | 1.91 | (1.68, 2.17) | <.0001 |

| Past year alcohol abuse/dep vs no past year alcohol abuse/depe | 2.70 | (2.47, 2.96) | <.0001 | 1.43 | (1.29, 1.58) | <.0001 |

| Past year parole/supervised release vs no past year parole/supervised release | 4.36 | (3.58, 5.31) | <.0001 | 1.13 | (0.84, 1.53) | .4266 |

| Past year probation vs no past year probation | 4.30 | (3.90, 4.75) | <.0001 | 1.17 | (1.02, 1.35) | .0305 |

| Sold illegal drugs vs did not sell drugs | 4.99 | (4.50, 5.54) | <.0001 | 1.49 | (1.27, 1.73) | <.0001 |

| Arrested/booked for breaking the law vs not arrested/booked | 4.51 | (4.29, 4.74) | <.0001 | 2.55 | (2.33, 2.80) | <.0001 |

| Seldom/never wears seatbelt as passenger vs sometimes/always wears seatbelt | 2.65 | (2.48, 2.84) | <.0001 | 1.24 | (1.08, 1.43) | .0021 |

| Seldom/never wears seatbelt as driver versus sometimes/always wears seatbelt | 2.95 | (2.71, 3.22) | <.0001 | 1.41 | (1.22, 1.64) | <.0001 |

| Had lifetime STD vs no lifetime STD | 1.51 | (1.32, 1.74) | <.0001 | 1.12 | (0.95, 1.32) | .1613 |

| Stole/tried to steal item ≥ $50.00 vs did not steal | 3.09 | (2.67, 3.58) | <.0001 | 1.07 | (0.88, 1.30) | .5166 |

| Attacked someone w/intent to harm vs did not attack someone | 2.65 | (2.35, 2.99) | <.0001 | 1.00 | (0.85, 1.17) | .9562 |

| Drove under influence of alcohol/drugs vs no DUI | 2.52 | (2.33, 2.71) | <.0001 | 1.52 | (1.41, 1.64) | <.0001 |

| Indicators of Social Instability | ||||||

| Approached by someone selling drugs vs not approached by someone selling drugs | 2.75 | (2.58, 2.92) | <.0001 | 1.53 | (1.41, 1.67) | <.0001 |

| Moved ≥ once per year vs no moves (past 5 years) | 2.71 | (2.49, 2.96) | <.0001 | 2.27 | (2.05, 2.52) | <.0001 |

| Agree/strongly agree “My religious beliefs are important to me” vs disagree/strongly disagree | 0.57 | (0.54, 0.60) | <.0001 | 1.12 | (1.03, 1.21) | .0097 |

| Agree/strongly agree “Religious beliefs influence my decisions” vs disagree/strongly disagree | 0.52 | (0.49, 0.55) | <.0001 | 0.77 | (0.71, 0.84) | <.0001 |

| Often attends religious services vs never attends religious services | 0.25 | (0.23, 0.28) | <.0001 | 0.37 | (0.33, 0.42) | <.0001 |

Notes. OR = Odds Ratio; AOR= Adjusted Odds Ratio (odds of current smoking for each predictor adjusting for all other predictors (e.g., males are 1.15-times more likely to smoke than females adjusting for all other variables in the model).

Persons who reported ever smoking all or part of a cigarette in the 30 days preceding the interview AND smoking ≥ 100 cigarettes in their lifetime.

Defined by the NSDUH as a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder, other than a developmental or substance use disorder, that met the criteria found in the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). For details on the methodology, see Section B.4.3 in Appendix B of the Results from the 2011 NSDUH: Mental Health Findings.

The five racial categories (White, Black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Other) are mutually exclusive and exclude Hispanic ethnicity. “Other” includes Native Hawaiians or Other Pacific Islanders and persons of two or more races. Persons identified as Hispanic might be of any race.

Based on reported family income and poverty thresholds published by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Drug and alcohol abuse and dependence criteria used in the NSDUH were defined based upon the criteria listed in the DSM-IV. Illicit substances included marijuana, hallucinogens, heroin, inhalants, tranquilizers, cocaine, pain relievers, stimulants, and sedatives. Obesity was not included in the regression analyses because it was only included in the 2013 survey.

Discussion

The pattern of results we observed in which the high prevalence of cigarette smoking among GED recipients was an outlier to an otherwise orderly graded inverse relationship between educational attainment and smoking prevalence is consistent with the results reported in other U.S. nationally representative adult samples (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012; King et al., 2012). Unlike previous reports, we have attempted to provide a context for that pattern of results by demonstrating that the outlier that the GED poses to this relationship is not specific to smoking. Indeed, in the present study we identified 19 risk indicators in addition to cigarette smoking that differed significantly between GED holders relative to high school dropouts and graduates. Although a majority of GED holders did not endorse many of the risk indicators, these data nonetheless provide compelling support that on average, GED holders are more likely than those with other educational attainment levels to exhibit a general high-risk profile of which cigarette smoking is one characteristic.

The present characterization of GEDs as exhibiting a general high-risk profile is consistent with reports that have been published on GED recipients in other domains (e.g., military, labor force). For example, compared to high school graduates, GED holders have been shown to have higher attrition rates in the military (Ulmer and Steffensmeier, 2014), and among those who pursue post-secondary education, GED holders are more likely to leave college or earn lower grades (Cameron and Heckman, 1993). Relative to high school dropouts, GED holders are less frequently employed, earn lower hourly wages, and experience greater job turnover (Heckman and Rubinstein, 2001). As noted previously, economists have observed that GED holders are more likely to engage in a variety of delinquent behaviors than high school dropouts without a GED or graduates (e.g., shoplifting, illegal drug use [Heckman and Rubinstein, 2001]). Finally, and perhaps most important to the purposes of the present study, those with GED's exhibit disproportionately higher prevalence of other health risk behaviors and associated conditions including obesity, physical inactivity, binge drinking, and disrupted sleep (Gillum et al., 2011). However, it is worth noting that the mechanisms that underpin vulnerability to health risk behaviors among GED holders may differ from the mechanisms involved in modifying those behaviors. For example, despite GED holders having approximately two-times greater odds of smoking than high school dropouts and high school graduates, the odds of quitting among GED holders and high school dropouts who reported smoking at least 100 lifetime cigarettes did not differ from each other, and high school graduates had less than 1.5-times greater odds of quitting than both of these lower two educational levels although these comparisons were statistically significant. The current study is the first to our knowledge to report the prevalence of quitting among those with GEDs and suggests that, at least in the present young adult sample, GED holders are similarly adept at quitting smoking as high school dropouts without a GED and not substantially less adept at doing so than high school graduates. Put differently, whatever set of factors contributes to the disproportionately high smoking prevalence seen among GED holders relative to those with similar levels of educational attainment does not appear to extend to quitting smoking.

The present results suggest at least two related lines for future research that may contribute a more complete account of the higher smoking prevalence, and/or the general pattern of increased risk-related characteristics, among GED holders compared to high school dropouts without a GED and high school graduates. First, those with GEDs may share common early-life experiences that precipitate the development of this high-risk profile. Including additional risk indicators related to early life experience in future research may account for a greater proportion of the variance in smoking prevalence and other risk behaviors across education levels. For example, some of the NSDUH items administered exclusively among youth aged 12-17 years (e.g., drug use among peers and friends; rules and limitations set by one's parents; participation in school-, community-, or faith-based activities) may be worth examining. Indeed, it is worth highlighting here that even when adjusting for all other risk indicators, those items that we conceptualized as protective factors (e.g., endorsing the importance of religious beliefs, attending religious services often) still remained significant predictors of current smoking. It will be important for future research to consider not only additional risk indicators but also additional protective factors that, when absent, might also contribute to the increased smoking prevalence among those with GEDs.

In addition to expanding the number and type of risk indicators, investigating potential neuropsychological mechanisms that might underpin the generalized risk profile that appears to be more prevalent among GED holders compared to other educational attainment levels is an important research direction to pursue. These mechanisms may include individual differences in the ability to defer gratification, time preference, self-control, self-efficacy (Zajacova and Everett, 2014), and/or deficits in executive functioning domains (e.g., planning, inhibitory control [Bickel et al., 2014; Hall and Marteau, 2014; Moody et al., 2014]). It is worth emphasizing that these two avenues for future research are not mutually exclusive. For example, the field of epigenetics is demonstrating substantial influences of early environmental events (e.g., maternal smoking during pregnancy) on adult intellectual development and disease risk (e.g., increased risk of metabolic diseases and cognitive impairments [Bakker and Jaddoe, 2011]). In addition to prenatal factors, research also implicates early parent-child interactions and cognitive stimulation in the home (e.g., presence of books) in neural development, with influences in particular on brain regions involved in language and executive functioning (Hackman et al., 2010). Thus it is quite feasible that the high-risk profile exhibited by some respondents with GEDs in this study emerges as a consequence of social, environmental and biological factors that interact in a reciprocal manner throughout the course of development.

The social, environmental and biological factors described above may be related not only to the development of a riskier profile but also to one's educational choices (e.g., earning a GED certificate rather than a high school diploma). For example, the estimated 20-30 hours it takes to prepare for the GED exam is a substantially lesser commitment than the approximately 410 hours of core curriculum classes taken each year by students pursuing a high school diploma (Boesel et al., 1998) and may therefore appeal to those who struggle with delaying gratification. While dropping out of high school without earning a GED is the least effortful choice, it is feasible that the combination of executive functioning difficulties with intellectual capabilities equivalent to those of high school graduates or higher underpins attraction to the GED degree. Indeed, GED holders have been characterized by economists as “wise guys” who are intellectually capable but lack the ability to think ahead, persist in tasks, and adapt to their environments (Cameron and Heckman, 1993). Another contributor to earning a GED is the opportunity to do so associated with imprisonment, and some of the GED holders in the current sample who endorsed items indicating involvement with the criminal justice system (e.g., past year parole or probation) may have earned their GED while incarcerated.

One notable limitation of the present report was our use of a restricted age group, as the prevalence of cigarette smoking in nationally representative samples is generally reported among a broader age range of U.S. adults (Agaku et al., 2014; Garrett et al., 2013; Jamal et al., 2014; King et al., 2012), thereby rendering the present sample a less than ideal group for comparison purposes. Additionally it is unclear based on the present results whether the profile among adults aged 18-25 years with a GED characterized in the present study generalizes to older adults who hold that degree. A second limitation is that the NSDUH is a cross-sectional survey; thus the directionality of the relationship between earning a GED and engaging in risk behaviors including cigarette smoking is unclear and should be addressed in future longitudinal studies. Finally, it is worth repeating that although 19 risk indicators examined in this study were more prevalent among GED holders relative to high school dropouts and graduates, a majority of those with GEDs did not endorse these items. Thus is may be worthwhile for future research to parse out those characteristics that distinguish the subgroup of individuals with the GED degree who exhibit this risky repertoire.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the present results have both research-related and practical implications. First, our results caution against placing GED holders in the same educational category as either high school dropouts or high school graduates in epidemiological studies, as has been done in other reports on the prevalence of cigarette smoking (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013) and chronic disease (e.g., diabetes [Saydah and Lochner, 2010]). Regarding practical implications, the presence of a general high-risk profile among GED holders suggests that it may be worthwhile to employ preventive strategies targeting this group. For example, the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (NREPP), developed by SAHMSA, contains information on numerous effective, school-based prevention programs focused on specific topics such as evaluating and resisting pro-drug social influences (e.g., Project ALERT [Gorman and Conde, 2010; Ringwalt et al., 2009]), as well as more general programs that target social and environmental risk factors for substance use, violence, and other risky behaviors (e.g., LifeSkills Training [Griffin et al., 2003; Spoth et al., 2008]). Implementing these programs in communities with low high school graduation rates may help to attenuate the relationship between low educational attainment and engagement in risk behaviors than appears to be the case currently

To our knowledge, the present report represents the first attempt in the tobacco literature to place the strikingly high smoking prevalence among GED recipients into a broader context. To this end, we provide empirical support for the presence of a general high-risk profile among GED holders of which smoking appears to be just one of many components. In addition to equipping tobacco researchers with a broader conceptual framework for understanding the relationship between socioeconomic status and risk factors for chronic disease such as cigarette smoking, the present results also suggest important avenues for future research that may ultimately provide a more complete account of the social, environmental, and biological contributors to the high-risk profile demonstrated among those with GEDs.

Highlights.

Investigation of strikingly high smoking prevalence among those with GED degrees

Compared risk indicators between those with GEDs and HS dropouts/graduates

Those with GEDs differ from HS dropouts/graduates across many risk indicators

Other risk indicators accounted for 25-30% of the variance in GED smoking prevalence

This tendency to smoke appears to be just one member of a generally risky repertoire

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by NIDA and FDA Tobacco Centers of Regulatory Science Award P50DA036114, NIDA Institutional Training Award T32DA07242 and NIGMS Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence Center Award P20GM103644. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: None to declare.

References

- Agaku I, King B, Dube SR. Current cigarette smoking among adults - United States 2005-2012. 2014:29–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker H, Jaddoe VW. Cardiovascular and metabolic influences of fetal smoke exposure. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2011;26:763–70. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9621-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Moody L, Quisenberry AJ, Ramey CT, Sheffer CE. A Competing Neurobehavioral Decision Systems model of SES-related health and behavioral disparities. Prev. Med. 2014;68:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesel D, Alsalam N, Smith TM. Educational and labor market performance of GED recipients. Research Synthesis. 1998 Available online at: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED416383.pdf.

- Cameron SV, Heckman JJ. The nonequivalence of high school equivalents. Journal of Labor Economics. 1993;11:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Current cigarette smoking among adults-United States, 2011. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2012;61:889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged≥ 18 years with mental illness-United States, 2009-2011. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2013;62:81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management science. 1963;9:458–67. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett BE, Dube SR, Winder C, Caraballo RS. Cigarette Smoking—United States, 2006-2008 and 2009-2010. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report—United States, 2013. 2013;62:81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum RF, Anyikude S, Lea K. Categorizing the attainment of a GED in studies of chronic disease. Public Health Rep. 2011;126:160. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman DM, Conde E. The making of evidence-based practice: The case of Project ALERT. Children and youth services review. 2010;32:214–22. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Botvin GJ, Nichols TR, Doyle MM. Effectiveness of a universal drug abuse prevention approach for youth at high risk for substance use initiation. Prev. Med. 2003;36:1–7. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackman DA, Farah MJ, Meaney MJ. Socioeconomic status and the brain: mechanistic insights from human and animal research. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;11:651–9. doi: 10.1038/nrn2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall PA, Marteau TM. Executive function in the context of chronic disease prevention: theory, research and practice. Prev. Med. 2014;68:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ, Rubinstein Y. The importance of noncognitive skills: Lessons from the GED testing program. Am. Econ. Rev.:145-49. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Agaku IT, O'Connor E, King BA, Kenemer JB, Neff L. Current cigarette smoking among adults--United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014;63:1108–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EO, Novak SP. Onset and persistence of daily smoking: the interplay of socioeconomic status, gender, and psychiatric disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104:S50–S57. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenkel DS, Lillard DR, Mathios AD. The roles of high school completion and GED receipt in smoking and obesity. National Bureau of Economic Research. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- King B, Dube S, Tynan M. Current tobacco use among adults in the United States: Findings from the National Adult Tobacco Survey. Am. J. Public Health. 2012;102:e93–e100. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AJ, Crombie IK, Smith WC, Tunstall-Pedoe HD. Cigarette smoking and employment status. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991;33:1309–12. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90080-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leino-Arjas P, Liira J, Mutanen P, Malmivaara A, Matikainen E. Predictors and consequences of unemployment among construction workers: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 1999;319:600–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7210.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Willoughby BL. Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: Associations, explanations, and implications. Psychol. Bull. 2009;135:69–93. doi: 10.1037/a0014213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody LN, Frankck CT, Mueller ET, Carter A, Jarmolowicz DP, Gatchalian KM, Bickel WK. Executive functioning deficits in alcohol-dependent and alcohol- and cocaine-dependent individuals. American Psychological Association Conference; Toronto. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reingle Gonalez JM, Salas-Wright CP, Connell NM, Jetelina KK, Clipper SJ, Businelle MS. The long-term effects of school dropout and GED attainment on substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;158:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringwalt CL, Clark HK, Hanley S, Shamblen SR, Flewelling RL. Project ALERT: A cluster randomized trial. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2009;163:625–32. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Badger GJ. A comparison of cocaine-dependent cigarette smokers and non-smokers on demographic, drug use and other characteristics. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;40:195–201. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA . Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, MD: 2013. Results from the 2012 national survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings. [Google Scholar]

- Saydah S, Lochner K. Socioeconomic status and risk of diabetes-related mortality in the U.S. Public Health Rep. 2010;125:377–88. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth RL, Randall GK, Trudeau L, Shin C, Redmond C. Substance use outcomes 51/2 years past baseline for partnership-based, family-school preventive interventions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmer JT, Steffensmeier D. The Nurture Versus Biosocial Debate in Criminology: On the Origins of Criminal Behavior and Criminality. SAGE Publications Ltd; London: 2014. The Age and Crime Relationship: Social Variation, Social Explanations. SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Walker C, Ainette MG, Wills TA, Mendoza D. Religiosity and substance use: test of an indirect-effect model in early and middle adolescence. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2007;21:84–96. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajacova A, Everett BG. The nonequivalent health of high school equivalents. Social science quarterly. 2014;95:221–38. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]