Abstract

Histone methylation is widely present in animals, plants and fungi, and the methylation modification of histone H3 has important biological functions. Methylation of Lys9 of histone H3 (H3K9) has been proven to regulate chromatin structure, gene silencing, transcriptional activation, plant metabolism, and other processes. In this work, we investigated the functions of a H3K9 methyltransferase gene BcDIM5 in Botrytis cinerea, which contains a PreSET domain, a SET domain and a PostSET domain. Characterization of BcDIM5 knockout transformants showed that the hyphal growth rate and production of conidiophores and sclerotia were significantly reduced, while complementary transformation of BcDIM5 could restore the phenotypes to the levels of wild type. Pathogenicity assays revealed that BcDIM5 was essential for full virulence of B. cinerea. BcDIM5 knockout transformants exhibited decreased virulence, down-regulated expression of some pathogenic genes and drastically decreased H3K9 trimethylation level. However, knockout transformants of other two genes heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) BcHP1 and DNA methyltransferase (DIM2) BcDIM2 did not exhibit significant change in the growth phenotype and virulence compared with the wild type. Our results indicate that H3K9 methyltransferase BcDIM5 is required for H3K9 trimethylation to regulate the development and virulence of B. cinerea.

Keywords: Botrytis cinerea, histone H3 lysine 9 methyltransferase, H3K9 trimethylation, BcDIM5, virulence, development

Introduction

Genetic information of eukaryotes is stored as chromatin, which consists of genomic DNA, histones, and a wide array of chromosomal proteins. In eukaryotes, DNA is wrapped around histones, which are subjected to a variety of covalent modifications, such as methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitylation (Widom, 1998). Histone methylation mainly occurs on the side chains of lysines and arginines. Lysines may be mono-, di-, or tri-methylated, whereas arginines may be mono-, symmetrically, or asymmetrically di-methylated (Bedford and Clarke, 2009; Lan and Shi, 2009). Lysine methylation is highly selective, and K4 and K9 of histone H3 are the best characterized sites (Liu et al., 2010). In general, lysine 9 of histone H3 (H3K9) is associated with transcriptionally inactive heterochromatin, and is a well-conserved epigenetic mark for heterochromatin formation and transcriptional silencing, while H3K4 methylation is associated with transcriptionally active euchromatin (Berger, 2007).

The first histone lysine methyltransferase to be identified was SUV39H1, which targets H3K9 (Rea et al., 2000). Strikingly, all of the histone lysine methyltransferases that methylate N-terminal lysines contain a so-called SET domain that harbors the enzymatic activity. Neurospora crassa DIM5 can specifically tri-methylate H3K9 (Xiao et al., 2003). Orthologs of SUV39H1, which are named as Clr4 in yeast (Nakayama et al., 2001), Su(var)3-9 in Drosophila (Tschiersch et al., 1994), and Suv39h1 in mice (O'Carroll et al., 2000), are the major heterochromatic H3K9 methyltransferases and play a dominant role in pericentric heterochromatin formation.

Botrytis cinerea (teleomorph: Botryotinia fuckeliana) causes severe loss in more than 200 crop species worldwide. It is most destructive on the mature or senescent tissues of dicotyledonous hosts and ornamentals (Williamson et al., 2007). B. cinerea is a typical necrotroph fungus, whose infection strategies include killing of the host cells and feeding on the dead tissues by secreting cell wall degrading enzymes, and toxic metabolites that induce cell death prior to the invasion of hyphae (Siewers et al., 2005; Choquer et al., 2007). Two polyketide synthases (BcPKS6 and BcPKS9) are required for phytotoxin botcinic acid biosynthesis and virulence (Dalmais et al., 2011). Two velvet-like genes (BcVeA and BcVELB) are involved in the regulation of fungal development, oxidative stress response, and virulence in B. cinerea (Yang et al., 2013). Presilphiperfolan-8 beta-alpha synthase BcBOT2 is responsible for the first step of botrydial synthesis (Wang et al., 2009), whereas BcBOT1 is a P450 monooxygenase that acts in the later step of biosynthesis (Siewers et al., 2005). Methylation of histone H3 is required for the normal development of N. crassa (Adhvaryu et al., 2005), and methylation of lysine H3K9 is a mark that primes the formation of heterochromatin and a critical chromatin landmark for genome stability (Rivera et al., 2015). Here, to better understand the functions of histone H3 methylation in B. cinerea, we identified a K9 histone H3 methyltransferase gene BcDIM5 in B. cinerea through Blastp searching the homologs of DIM5 in N. crassa. This protein contains a PreSET domain, a SET domain, and a PostSET domain, which is the typical structure of a H3K9 methyltransferase. We characterized the function of BcDIM5. The results indicate that BcDIM5 is required for hyphal growth and the production of conidiophores and sclerotia. Furthermore, pathogenicity assays indicate that BcDIM5 is essential for full virulence of B. cinerea. BcDIM5 knockout transformants showed down-regulated expression of some pathogenic genes and H3K9 trimethylation was drastically decreased in vivo, but two other genes BcHP1 and BcDIM2 were not required for the development and virulence of B. cinerea. Taken together, these results indicate that BcDIM5 is important for the development and virulence of B. cinerea.

Materials and methods

Fungal strains and culture conditions

B. cinerea wild-type strain B05.10 was used in this study. The fungus was grown on potato dextrose agar (200 g potato, 20 g glucose per liter, 2% agar), and incubated for 7–30 days at 20°C Knockout transformants were cultured on PDA amended with 75 μg/mL hygromycin B (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA). Complementary transformants were cultured on PDA amended with 75 μg/mL hygromycin B and 50 μg/mL G418. Escherichia coli strain DH5α was used to propagate all of the plasmids, and Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 was used for the transformation of fungi. Seedlings of Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Columbia-0) were grown in the greenhouse at 20 ± 2°C for 1 month under a 12 h light/dark cycle with 70% relative humidity.

Gene knockout and complementation by protoplast transformation

BcDIM5, BcDIM2, and BcHP1 were knocked out in the WT strain B05.10 using the hygromycin B-resistance gene (Hyg) to replace the partial sequences of BcDIM5, BcDIM2, and BcHP1 (Figure S1). To construct the ΔBcDIM5 disruption vector, a 753-bp DNA fragment named 3U with the EcoRI restriction sites at 5′- and 3′-terminus and a 740-bp DNA fragment named 3D with the EcoRI restriction sites at 5′- and 3′-terminus were PCR-amplified from genomic DNA of strain B05.10. Using pKS1004 vector as the template, the 740-bp HY fragments were amplified by primers HYG-F and HY-R, and the 1133-bp YG fragments were amplified by primers YG-F and HYG-R. The 3U and HY fragments were fused with PCR to obtain a 1465-bp fragment named 3UHY, and 3D and YG fragments were fused with PCR to obtain a 1936-bp fragment named 3DYG. After digestion with enzymes EcoRI, the DNA fragments 3UHY and 3DYG were separately collected and inserted into the linearized plasmid pBluescriptII KS1004 for sequencing. 3UHY and 3DYG were individually linearized and transformed separately into the protoplasts of B. cinerea wild type strain B05.10 using the PEG-mediated protoplast transformation technique (Wei et al., 2013). For complementation assays, the 5.75-kb PCR product containing a 3-kb upstream sequence (which contained the endogenous promoter), a full-length BcDIM5 gene coding region, and a 1-kb downstream sequence was amplified from the wild type strain B05.10 genomic DNA using primers DIM-5-CF-BamHI and DIM-5-CR-BamHI and cloned into the same sites of p3300neoIII to generate the BcDIM5 complementary vector p3300neoIII-BcDIM5, which was then transformed into BcDIM5 knockout transformants using the A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation technique.

DNA extraction and southern blot analysis

The wild-type strain and knockout transformants were cultured on PDA plates covered with cellophane membranes, and mycelia were harvested at 3 days post inoculation (dpi). Genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB method. Southern blot analysis was conducted following the method described by Wei et al. (2016). The genomic DNA of 15 μg was completely digested with HindIII, separated by electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gel and transferred onto a Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The probe was amplified the specific fragment of hygromycin hph gene and be labeled by DIG (GE healthcare). The nylon membranes were autoradiographed and analyzed using Bio-imaging analyser BAS-1800II (FUJIFILM, Tokyo, Japan).

Pathogenicity tests

Pathogenicity tests of transformed and wild-type B. cinerea strains were performed on Arabidopsis, tomato, soybean by the inoculation of detached leaves with young non-sporulating mycelium or conidial suspensions. Leaves were harvested from 4-week-old plants and placed in a transparent plastic box lined with tissue moistened with sterile water. Leaves were inoculated with 2-mm-diameter plugs of 3-day-old mycelium. Alternatively, conidia were collected from 10-day-old plates and suspended in water to a final concentration of 5 × 105 conidia/mL. Droplets of 5 μL were applied to the leaves. Storage boxes containing inoculated leaves were incubated in a growth cabinet at 20°C with 16 h of daylight. Disease development on leaves was recorded daily as the radial spread from the inoculation point to the lesion margin. Pathogenicity assays on leaves were repeated three times using at least three leaves per assay.

Quantitative real-time PCR

The mRNA transcripts were measured using a SYBR Green I real-time PCR assay in a CFX96 real-time PCR detection systems (Applied Biosystems). The thermal cycling conditions were 95°C for 2 min for predegeneration, 40 cycles of 95°C for 20 s for denaturation, 60°C for 20 s for annealing and 72°C for 20 s for extension. All of the reactions were run in triplicate by monitoring the dissociation curve to control the dimers. The B. cinerea β -tubulin gene was used as reference gene. qRT-PCR was used to examine the expression of B. cinerea Bcsod1 (BC1G_00558), BcSpl1 (BC1G_02163), BcVeA (BC1G_02976), BcBOT2 (BC1G_06357), Bcmp3 (BC1G_07144), BcVELB (BC1G_11858), BcPKS (BC1G_15837), Bcbot1 (BC1G_16381), BcDIM2 (BC1G_12419), BcHP1 (BC1G_06432), and BcDIM5 (BC1G_11188). The primers for qRT-PCR are listed in Table S1.

Western blot analysis of H3K9 trimethylates

Mycelia were harvested and ground in liquid nitrogen. Two hundred milligrams powders were resuspended in 400 μL cell lysis buffer on ice (Beyotime, China). Total proteins of mycelium extract were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min, and the supernatant was used for western-blot analysis. Proteins were separated by 12% PAGE and electroblotted to a nitrocellulose membrane at 25 V for 40 min. The membrane was blocked with Tris-buffered saline plus Tween 20 containing 5% skim milk powder for 2 h at room temperature. After incubation with primary antibody and then with secondary antibody, the membrane was transferred for protein detection using a Thermo SuperSignal West Pico kit (Thermo Scientific). The sources and dilutions of antibodies were as follows: Histone H3 monoclonal antibody (Abmart, at 1: 2000), Histone H3 tri methyl K9 monoclonal antibody (Abmart, at 1: 2000), and goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Abmart, at 1: 5000).

Results

BC1G_11188 was predicted as a histone H3 lysine 9 methyltransferase

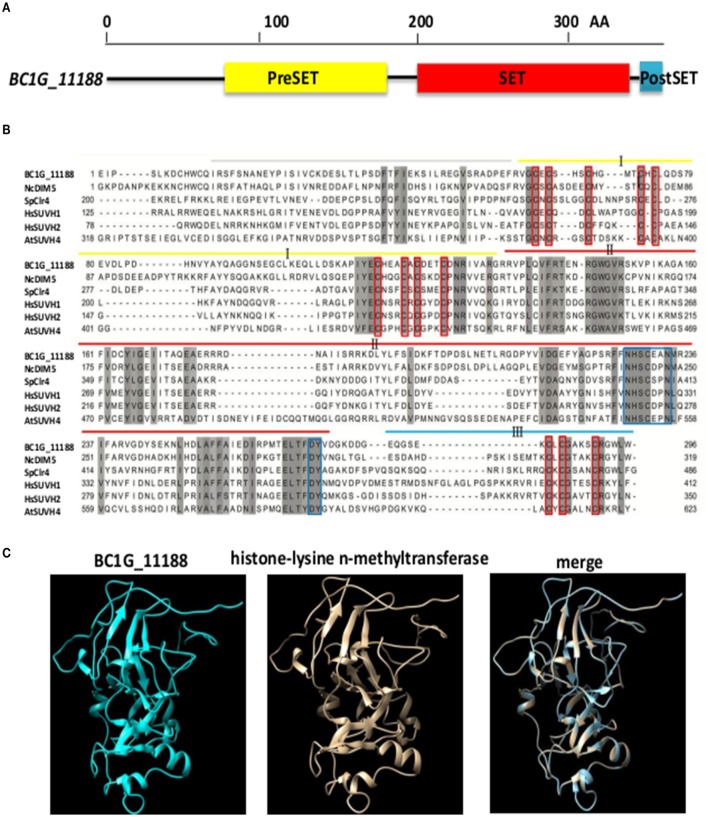

The B. cinerea BC1G_11188 gene (GenBank accession: XM_001550366.1) is a single copy gene consisting of 4 exons and 3 introns and encoding a peptide of 357 amino acid residues. The protein contains the typical domain structures of H3K9 methyltransferase (Figure 1A), including a PreSET domain, a SET domain, and a PostSET domain (Rea et al., 2000; Tamaru and Selker, 2001; Adhvaryu et al., 2005). SET domain contains two conserved sequences of NHXCXPN and DY, which can form an AdoMet binding site and the catalytic activity site of methyl transferase, and participates in the formation of DIM5 hydrophobic structure (Zhang et al., 2002). PreSET domain contains nine conserved cysteine residues that can be combined with three zinc ions to form a zinc cluster. PostSET domain contains three conserved cysteine residues involved in the binding of DIM5 to AdoMet (Figure 1B). Similar to the histone lysine methyltransferases of NcDIM5, SpClr4, HsSUVH1, HsSUVH2, and AtSUVH4, BC1G_11188 includes cysteine-rich sequences that flank a SET domain (Figure 1B). The results of Bioinformatics Toolkit HHpred analysis indicate that the structure of BC1G_11188 is similar to the three-dimensional structure of histone lysine n-methyltransferase (Template: c4qeoA, Confidence: 100%; Figure 1C). In summary, the protein coded by BC1G_11188 resembles histone H3 lysine 9 methyltransferase. Thus, we designated this gene which was derived from the homologs of DIM5 in N. crassa as “BcDIM5.”

Figure 1.

BcDIM5 was predicted as a H3K9 methyltransferase in B. cinerea. (A) Schematic illustrations of BcDIM5. The conserved domains were predicted by the SMART web site. (B) Multiple sequence alignment of H3K9 methyltransferase. Comparison of the DIM5 from Botrytis cinerea (BcDIM5), Neurospora crassa (NcDIM5), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (SpClr4), Homo sapiens (HsSUVH1 and HsSUVH2), and Arabidopsis thaliana (AtSUVH4). The more similar the amino acids are, the darker the background is. (C) Representation of the three-dimensional structure of H3K9 methyltransferase and predicted BcDIM5. Total residues were modeled with 100% confidence by the single highest scoring template H3K9 methyltransferase (c4qeoA) in the Phyre database.

Generation of BcDIM5 knockout and complementary transformants

To examine the function of BcDIM5, the BcDIM5 knockout transformants were generated through homologous recombination of the BcDIM5 open reading frame with a gene conferring hygromycin resistance (HYG) (Figure S1A). Positive knockout transformants were amplified with PCR (Figure S1B), and three BcDIM5 knockout transformants (21, 24, and 25) were identified. Reverse transcription PCR was employed to detect the BcDIM5 gene expression. The results showed that there were no transcripts in the three knockout transformants (Figure S1C). Two transformants (ΔBcDIM5-21 and ΔBcDIM5-24) were further confirmed by Southern blot analysis (Figure S1D). The mutant ΔBcDIM5-21 was used for phenotypic analysis and complemented with the full-length gene of wild typeBcDIM5. After being verified by PCR, the complemented strain BcDIM5-C1 was chosen for further study (Figure S1E).

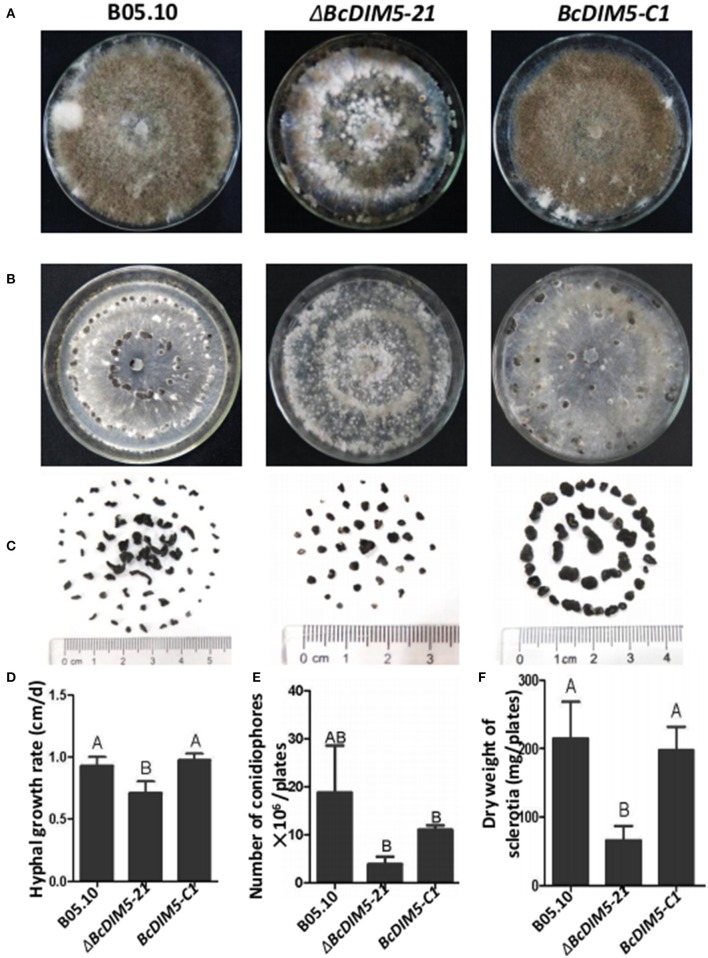

BcDIM5 played an important role in B. cinerea growth and development

To determine the role of BcDIM5 in the growth and development of B. cinerea, we compared the hyphal growth rate, the number of conidiophores and dry weight of sclerotia of the wild-type strain, ΔBcDIM5-21 strain and the BcDIM5-C1 complemented strain. Although BcDIM5 did not affect the morphology of tip hyphae (Figure S2), the hyphal growth rate was significantly reduced in ΔBcDIM5-21 strains, while this phenotype was restored after complementation (Figure 2D). BcDIM5 affected the development of conidiophores and sclerotia, and the wild-type strain could averagely produce 2 × 107 conidiophores per plate, while ΔBcDIM5-21 strains only produced 3 × 106 conidiophores per plate, and the conidiophore production of BcDIM5-C1 complemented strain was restored to 1.1 × 107 conidiophores per plate (Figures 2A,E). Although ΔBcDIM5-21 strain was able to produce conidiophores, the time required for conidiophore initiation was about 3–4 days longer than that for the normal strain. The dry weight of sclerotia produced by wild-type B. cinerea was 217 mg per plate, while ΔBcDIM5-21 strains only produced 57 mg sclerotia per plate, and the sclerotia was small and round. The sclerotia production of BcDIM5-C1 complemented strain was restored to 200 mg per plate, which was similar to that of the wild type (Figures 2B,C,F). These data clearly suggest that BcDIM5 knockout has a deleterious effect on hyphal growth and the development of conidiophores and sclerotia, meanwhile, the reduced hyphal growth rate of ΔBcDIM5-21 strains may delay conidiophore development and the sclerotia formation.

Figure 2.

Biological characterization of the wild-type strain, BcDIM5 knockout, and complemented transformants. (A) Comparison of the phenotypes of the BcDIM5 knockout and complemented strain. All the strains were grown on a PDA plate at 20°C for 15 days under a 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod. (B) Comparison of the phenotypes of the BcDIM5 knockout and complemented strain. All the strains were grown on a PDA plate at 20°C for 15 days under dark condition. (C) Sclerotia produced by strains on a PDA plate at 20°C for 30 days under dark condition. (D) Comparison of the hyphal growth rate of the BcDIM5 knockout and complemented strains. Three independent replications were performed. Bars indicate the standard error. The values are presented as the mean ± s.d. Differentiation was evaluated by t-test. Different letters on a graph indicate significant differences, P < 0.05. (E) Comparison of the number of conidiophores per plate of BcDIM5 knockout and complemented strains. Three independent replications were performed, P < 0.05. (F) Comparison of dry weight of sclerotia produced by BcDIM5 knockout and complemented strains. Three independent replications were performed, P < 0.05.

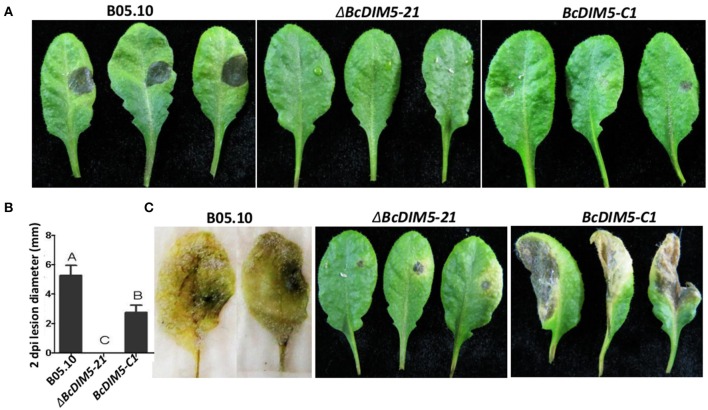

BcDIM5 knockout transformants exhibited decreased virulence

To determine the role of BcDIM5 in pathogenicity, detached Arabidopsis leaves were inoculated with conidia of the wild-type strain, ΔBcDIM5-21 strain and BcDIM5-C1 complemented strain. At 2 dpi, the inoculation of the wild-type strain B05.10 caused the formation of necrotic lesions with 5–6 mm diameter, and the leaves completely rotted away at 5 dpi (Figure 3). However, the leaves inoculated with the ΔBcDIM5-21 strains exhibited no necrotic lesions at 2 dpi, and only slight necrotic lesions in the infection site at 5 dpi. The pathogenicity of the BcDIM5-C1 complemented strain was only partially restored, as the diameter of the necrotic lesions was half of that induced by wild-type strain (Figure 3). We further used mycelium pieces to inoculate soybean and tomato leaves. Similar results were observed in ΔBcDIM5-21 and ΔBcDIM5-24 mutants. The virulence of the BcDIM5 knockout transformants was significantly reduced, and only small lesions were observed on the detached leaves of soybean and tomato (Figure S3), indicating that the virulence reduction is not host species-specific. These results indicate that BcDIM5 plays crucial roles in the virulence.

Figure 3.

Pathogenicity assays of the ΔBcDIM5-21 strain of B. cinerea on detached Arabidopsis leaves. (A) Four-week-old Arabidopsis detached leaves were inoculated by 5 μL conidia (concentration is 5 × 105 spores/mL) of wild type B05.10 (left), BcDIM5 knockout ΔBcDIM5-21 strain (middle), BcDIM5 complemented BcDIM5-C1 strain (right). The representative symptoms were photographed at 2 dpi. The experiment was repeated three times. (B) Comparison of the lesion diameters of the wild-type B05.10 strain, BcDIM5 knockout, and complemented strains. (C) Four-week-old Arabidopsis detached leaves were inoculated by 5 μL conidia (concentration is 5 × 105 spores/mL) of wild-type B05.10 strain (left), BcDIM5 knockout ΔBcDIM5-21 strain (middle), BcDIM5 complemented BcDIM5-C1 strain (right). The representative symptoms were photographed at 5 dpi after inoculation.

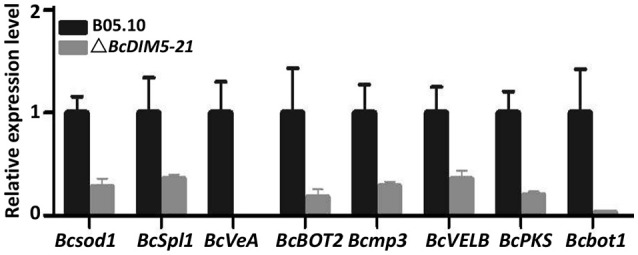

Pathogenic genes were down-regulated in BcDIM5 knockout transformants

To determine whether BcDIM5 regulates the expression of genes associated with pathogenesis, qRT-PCR was performed to analyze the expression of eight genes involved in the pathogenic process of B. cinerea based on previous studies. These eight genes included a Cu-Zn-superoxide dismutase gene Bcsod1, which is slightly increased by 0.5 mM H2O2 and significantly increased by 2.0 mM H2O2 (Rolke et al., 2004); a cerato-platanin family protein gene BcSpl1, which was induced in tobacco systemic resistance to two plant pathogens (Frías et al., 2013); two velvet-like genes BcVEA and BcVELB, which act as negative regulators for conidiation and melanin biosynthesis in B. cinerea (Yang et al., 2013); a presilphiperfolan-8 beta-alpha synthase gene BcBOT2, which encode the sesquiterpene synthase that is responsible for the committed step in the biosynthesis of botrydial (Wang et al., 2009); a mitogen-activated protein kinase gene Bcmp3, which is required for normal saprotrophic growth, conidiation, plant surface sensing and host tissue colonization (Rui and Hahn, 2007), a polyketide synthase gene BcPKS (Dalmais et al., 2011) and a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase gene Bcbot1 (Siewers et al., 2005). Expression analyses revealed that all of these eight genes were significantly down-regulated in the BcDIM5 knockout transformants compared with in the wild type (Figure 4). These data indicate that many pathogenic genes may be regulated by BcDIM5.

Figure 4.

Expression of the genes associated with pathogenesis in wild-type B05.10 strain and BcDIM5 knockout ΔBcDIM5-21 strains. Botrytis cinerea Bcsod1 (BC1G_00558), BcSpl1 (BC1G_02163), BcVeA (BC1G_02976), BcBOT2 (BC1G_06357), Bcmp3 (BC1G_07144), BcVELB (BC1G_11858), BcPKS (BC1G_15837), Bcbot1 (BC1G_16381).

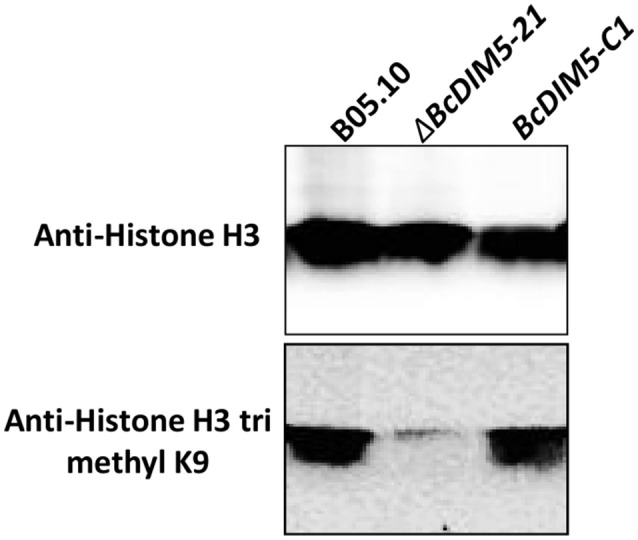

H3K9 trimethylation level was drastically decreased in BcDIM5 knockout transformants

To investigate the possible effects of DIM5 on the trimethylation of H3K9, we carried out western-blot to analyze the histone methylation level of the wild-type strain, ΔBcDIM5-21 and BcDIM5-C1 (Figure 5). All the strains presented equally robust signals when detected using the antibody histone H3. Notably, trimethylated H3K9 was detectable in bulk from the wild-type strain and BcDIM5-C1, while knockout transformant ΔBcDIM5-21 extinguished the trimethylated H3K9 signal, suggesting that BcDIM5 is dominantly responsible for the trimethylation of H3K9, and DIM5 may generate trimethylated H3K9 from unmodified histone H3 in vivo.

Figure 5.

Western-blot analysis of B. cinerea using antibodies histone H3 or trimethylated H3K9. In each case, 100 μg total proteins from wild-type B05.10, ΔBcDIM5-21, or BcDIM5-C1 strains were fractionated by SDS–PAGE (12%) and analyzed using the indicated antibodies. The monoclonal anti-Histone H3 was used as internal loading reference.

BcDIM2 and BcHP1 were not required for virulence in B. cinerea

In N. crassa, DIM5 trimethylates H3K9, and H3K9me3 directs DNA methylation through a complex containing heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) and the DNA methyltransferase DIM2. We also investigated whether DIM2 and HP1 play important roles in B. cinerea development and virulence. Based on the homology to N. crassa DIM2 and HP1, we cloned BcDIM2 (BC1G_12419) and BcHP1 (BC1G_06432) from B. cinerea. BcDIM2 contains typical domain structures of DNA methyltransferase and BcHP1 contains typical domain structures of CD (chromo domain) and CSD (chromo shadow domain; Paro and Hogness, 1991; Aasland and Stewart, 1995). RT–PCR analysis showed that BcDIM5, BcDIM2, and BcHP1 were all expressed in mycelium growth, sclerotial development and infection stages (Figure S4). BcDIM5 was constitutively expressed in these three stages, and BcDIM2 was significantly up-regulated during the infection stage, while BcHP1 was significantly down-regulated during the sclerotial development. Through homologous recombination methods, we got two knockout transformants ΔBcDIM2-16 and ΔBcHP1-7. There were no significant changes in the phenotype and number of produced conidiophores as well as in hyphal growth rate, dry weight of sclerotia and virulence among the wild-type, ΔBcDIM2-16 and ΔBcHP1-7 strains (Figure 6). Therefore, it can be concluded that BcDIM5 is required for the development and virulence whereas BcDIM2 and BcHP1 are not required for virulence in B. cinerea.

Figure 6.

Phenotypes of BcDIM2 and BcHP1 knockout transformants. (A) Comparison of the phenotypes of the ΔBcDIM2-16 and ΔBcHP1-7 knockout transformants. All the strains were grown on a PDA plate at 20°C for 15 days under a 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod. (B) Comparison of the phenotypes of the ΔBcDIM2-16 and ΔBcHP1-7 knockout transformants. All the strains were grown on a PDA plate at 20°C for 15 days under dark condition. (C) Pathogenicity assays of the ΔBcDIM2-16 and ΔBcHP1-7 knockout transformants of B. cinerea on detached Arabidopsis leaves. (D) Comparison of the hyphal growth rate of the ΔBcDIM2-16 and ΔBcHP1-7 knockout transformants. (E) Comparison of the number of conidiophores per plate of ΔBcDIM2-16 and ΔBcHP1-7 knockout mutants. (F) Comparison of dry weight of sclerotia produced by ΔBcDIM2-16 and ΔBcHP1-7 knockout transformants. (G) Comparison of the lesion diameters of the wild type, ΔBcDIM2-16 and ΔBcHP1-7 knockout transformants.

Discussion

Epigenetic alterations have important roles in certain biological processes such as cell phenotypic conversion, cell proliferation, and cell death by regulating transcriptional activity (Reik, 2007; Papp and Plath, 2011). The effect of epigenetic processes on transcription depends on various post-translational histone modifications (Wierda et al., 2015). The major histone modifications include acetylation, phosphorylation, methylation, and ubiquitylation (Arnaudo and Garcia, 2013). In this paper, we further described the extended role of H3K9 methyltransferase BcDIM5 in B. cinere. BcDIM5 was predicted as a methyltransferase with a SET domain (Figure 1). Although there is no evidence to show that BcDIM5 has methyltransferase activity in vitro, the structure-guided sequence alignment indicates that BcDIM5 has all of the methyltransferase characteristics, since all the aligned sequences were verified to be active methyltransferases previously (Zhang et al., 2002). In addition, as shown in Figure 5, western blot analysis using dimethyl H3K9 antibodies demonstrates that trimethylated H3K9 in BcDIM5 knockout transformants was drastically decreased and the phenotypes of the transformants were restored after complementation. These findings suggest that BcDIM5 has methyltransferase activity in vivo.

Analyses of the ΔBcDIM5 and complemented ΔBcDIM5 strains in this study indicate that ΔBcDIM5 is involved in sclerotia production. The ΔBcDIM5 transformants exhibited declined hyphal growth rate and reduced production of conidiophores and sclerotia (Figure 2). Declined growth rate of ΔBcDIM5 strians may affect the conidiophores development and sclerotia formation. In order to avoid this, we delayed the statistical time for development of conidiophores and sclerotia for 15 or 30 days, respectively. The results suggest that BcDIM5 is required for normal hyphal growth, conidiation, and sclerotia development. Additionally, in the pathogenicity assays, ΔBcDIM5 knockout transformants exhibited drastic reduction in virulence compared with wild type B05.10, while complemented ΔBcDIM5 strain could partially restore the phenotype (Figure 3). These results indicate that BcDIM5 plays a crucial role in the development and pathogenicity of B. cinerea, which is consistent with the results of previous studies. In histone methyltransferase G9a knockout mice, H3K9 methylation was drastically reduced, resulting in severe growth retardation and early lethality, which indicates that G9a is essential for early mouse embryo development (Tachibana et al., 2002, 2005). We then identified that eight pathogenic genes expression in BcDIM5 knockout transformants (Figure 4). Bcsod1, which is increased by H2O2 accumulation, is drastically declined in ΔBcDIM5 strain. Bcmp3, which is required for normal saprotrophic growth, is drastically declined in ΔBcDIM5 strain. BcSpl1, which is induced in systemic resistance, is drastically declined in ΔBcDIM5 strain. BcVeA and BcVELB are involved in the regulation of fungal development, oxidative stress response and virulence in B. cinerea, are drastically declined in ΔBcDIM5 strain. BcBOT1, BcBOT2, and BcPKS, associated with P450, botrydial and phytotoxin botcinic acid biosynthesis, respectively, are drastically declined in ΔBcDIM5 strain. Down-regulated eight pathogenic genes may lead to the drastically declined pathogenicity of ΔBcDIM5 strain. High throughput sequencing can identify the suppressed genes in ΔBcDIM5 strain, and the transcriptionally suppressive function of BcDIM5 may depend on its histone methyltransferase activity, but the molecular mechanism needs further investigation.

In N. crassa, all DNA methylation requires the DNA methyltransferase DIM2 (Kouzminova and Selker, 2001). DNA methylation also requires the histone H3K9 methyltransferase DIM5 (Tamaru and Selker, 2001; Tamaru et al., 2003) and heterochromatin protein HP1 (Freitag et al., 2004). H3K9 trimethylation directs DNA methylation through a complex containing HP1 and the DNA methyltransferase DIM2 (Honda et al., 2012). Based on the homology to N. crassa DIM2 and HP1, we cloned BcDIM2 and BcHP1. The ΔBcDIM2-16 and ΔBcHP1-7 knockout transformants showed no significant change in the development of conidiophores and sclerotia and virulence compared with wild type B05.10 (Figure 6). These results indicate that DNA methylation does not play important roles in this process. This growth phenotype is in agreement with the results of knockout of N. crassa DIM2 and Aspergillus nidulans dmtA (DNA methyltransferase homolog A), which did not affect the normal growth of the strain (Kouzminova and Selker, 2001; Lee et al., 2008). Although, DNA methylation is common in organisms such as bacteria, fungi, higher plants, and mammals, we did not use genomic DNA sequencing to detect the level of DNA methylation in B. cinerea, thus it is not known yet whether genomic DNA methylation is missing in ΔBcDIM2-16 knockout transformants. These data may be needed to explore the function of BcDIM2 in B. cinerea. HP1 plays a key role in heterochromatin formation and gene silencing, and is a positive regulator of active transcription in euchromatin (Kwon and Workman, 2011; Yearim et al., 2015). A number of recent studies have linked HP1 proteins to the DNA damage pathway, and HP1 proteins are independent of H3K9 trimethylation (Ayoub et al., 2008; Luijsterburg et al., 2009). Neurospora HP1 is required for normal growth of fungi (Freitag et al., 2004). In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the HP1 homologs swi6 and chp2/clo2 are important for normal growth but are not essential for viability (Halverson et al., 2000). In contrast, ΔBcHP1-7 knockout transformants in B. cinerea did not show noticeable growth defects. Most eukaryotes contain several HP1 homologs that display dramatic differences in both subcellular localizations and functions (Ryu et al., 2014). The function of BcHP1 in B. cinerea needs further research. Unlike that of BcDIM2 and BcHP1, knockout mutation of the histone methyltransferase gene BcDIM5 causes growth abnormality, pathogenic gene silencing and virulence reduction in B. cinerea, suggesting that it is histone methylation rather than DNA methylation that is involved in the development and virulence of B. cinerea. The detailed mechanisms of BcDIM5 to regulate the growth and pathogenic gene silencing need further investigation.

Author contributions

XZ, XL contributed equally to the article, XZ, XL, JC, and TC designed the research and wrote the paper; XZ, XL, YZ, and TC executed the experiments. XZ, XL, YZ, JC, JX, YF, DJ, and TC performed the data and analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest (201303025), Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (20130146120032) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Program No: 2013QC041).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01289

Identification of BcDIM5 knockout and complemented transformants. (A) Principle of homologous recombination. (B) BcDIM5 knockout transformants identified by PCR. (C) BcDIM5 knockout transformants identified by RT-PCR. (D) BcDIM5 knockout transformants identified by Southern blot using HYG labeled with DIG as probe. (E) BcDIM5 complemented transformants identified by PCR.

Morphological comparison of the hyphal tips of BcDIM5 knockout and complemented transformants.

Virulence assay of BcDIM5 knockout and complemented transformants on detached soybean and tomato leaves. Virulence was evaluated based on the lesion diameter at 20°C for 48 h. (A) Virulence assay of BcDIM5 knockout and complemented transformants on detached soybean leaves. (B) Virulence was evaluated based on the lesion diameter on soybean leaves. (C) Virulence assay of BcDIM5 knockout and complemented transformants on tomato leaves. (D) Virulence was evaluated based on the lesion diameter on tomato leaves.

Expression level of genes in different phase. Forty-eight hour indicates the wild type strain B05.10 grown in PDA for 48 h, which is the hyphal growth stage; 156 h indicates the wild-type strain B05.10 grown in PDA for 156 h, which is the sclerotial development stage. IN indicates the wild-type strain B05.10 inoculated on A. thaliana leaves for 48 h, which is the infection stage.

Primers used in the study.

References

- Aasland R., Stewart A. F. (1995). The chromo shadow domain, a second chromo domain in heterochromatin-binding protein 1, HP1. Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 3168–3173. 10.1093/nar/23.16.3168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhvaryu K. K., Morris S. A., Strahl B. D., Selker E. U. (2005). Methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 is required for normal development in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryotic Cell 4, 1455–1464. 10.1128/EC.4.8.1455-1464.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaudo A. M., Garcia B. A. (2013). Proteomic characterization of novel histone post-translational modifications. Epigenetics Chromatin 6:24. 10.1186/1756-8935-6-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub N., Jeyasekharan A. D., Bernal J. A., Venkitaraman A. R. (2008). HP1-beta mobilization promotes chromatin changes that initiate the DNA damage response. Nature 453, 682-U614. 10.1038/nature06875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford M. T., Clarke S. G. (2009). Protein arginine methylation in mammals: who, what, and why. Mol. Cell 33, 1–13. 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger S. L. (2007). The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature 447, 407–412. 10.1038/nature05915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquer M., Fournier E., Kunz C., Levis C., Pradier J. M., Simon A., et al. (2007). Botrytis cinerea virulence factors: new insights into a necrotrophic and polyphageous pathogen. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 277, 1–10. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00930.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmais B., Schumacher J., Moraga J., LE Pêcheur P., Tudzynski B., Collado I. G., et al. (2011). The Botrytis cinerea phytotoxin botcinic acid requires two polyketide synthases for production and has a redundant role in virulence with botrydial. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 564–579. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00692.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag M., Hickey P. C., Khlafallah T. K., Read N. D., Selker E. U. (2004). HP1 is essential for DNA methylation in neurospora. Mol. Cell 13, 427–434. 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00024-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frías M., Brito N., González C. (2013). The Botrytis cinerea cerato-platanin BcSpl1 is a potent inducer of systemic acquired resistance (SAR) in tobacco and generates a wave of salicylic acid expanding from the site of application. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14, 191–196. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00842.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halverson D., Gutkin G., Clarke L. (2000). A novel member of the Swi6p family of fission yeast chromo domain-containing proteins associates with the centromere in vivo and affects chromosome segregation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 264, 492–505. 10.1007/s004380000338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda S., Lewis Z. A., Shimada K., Fischle W., Sack R., Selker E. U. (2012). Heterochromatin protein 1 forms distinct complexes to direct histone deacetylation and DNA methylation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, S471. 10.1038/nsmb.2274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzminova E., Selker E. U. (2001). dim-2 encodes a DNA methyltransferase responsible for all known cytosine methylation in Neurospora. EMBO J. 20, 4309–4323. 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S. H., Workman J. L. (2011). The changing faces of HP1: from heterochromatin formation and gene silencing to euchromatic gene expression: HP1 acts as a positive regulator of transcription. Bioessays 33, 280–289. 10.1002/bies.201000138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan F., Shi Y. (2009). Epigenetic regulation: methylation of histone and non-histone proteins. Sci. China C Life Sci. 52, 311–322. 10.1007/s11427-009-0054-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. W., Freitag M., Selker E. U., Aramayo R. (2008). A cytosine methyltransferase homologue is essential for sexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS ONE 3:e2531. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Lu F., Cui X., Cao X. (2010). Histone methylation in higher plants. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 64, 395–420. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.091939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luijsterburg M. S., Dinant C., Lans H., Stap J., Wiernasz E., Lagerwerf S., et al. (2009). Heterochromatin protein 1 is recruited to various types of DNA damage. J. Cell Biol. 185, 577–586. 10.1083/jcb.200810035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama J., Rice J. C., Strahl B. D., Allis C. D., Grewal S. I. (2001). Role of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in epigenetic control of heterochromatin assembly. Science 292, 110–113. 10.1126/science.1060118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Carroll D., Scherthan H., Peters A. H., Opravil S., Haynes A. R., Laible G., et al. (2000). Isolation and characterization of Suv39h2, a second histone H3 methyltransferase gene that displays testis-specific expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 9423–9433. 10.1128/MCB.20.24.9423-9433.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp B., Plath K. (2011). Reprogramming to pluripotency: stepwise resetting of the epigenetic landscape. Cell Res. 21, 486–501. 10.1038/cr.2011.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paro R., Hogness D. S. (1991). The Polycomb protein shares a homologous domain with a heterochromatin-associated protein of Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 263–267. 10.1073/pnas.88.1.263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea S., Eisenhaber F., O'Carroll D., Strahl B. D., Sun Z. W., Schmid M., et al. (2000). Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases. Nature 406, 593–599. 10.1038/35020506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reik W. (2007). Stability and flexibility of epigenetic gene regulation in mammalian development. Nature 447, 425–432. 10.1038/nature05918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C., Saavedra F., Alvarez F., Díaz-Celis C., Ugalde V., Li J., et al. (2015). Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 occurs during translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 9097–9106. 10.1093/nar/gkv929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolke Y., Liu S. J., Quidde T., Williamson B., Schouten A., Weltring K. M., et al. (2004). Functional analysis of H2O2-generating systems in Botrytis cinerea: the major Cu-Zn-superoxide dismutase (BCSOD1) contributes to virulence on French bean, whereas a glucose oxidase (BCGOD1) is dispensable. Mol. Plant Pathol. 5, 17–27. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00201.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui O., Hahn M. (2007). The Slt2-type MAP kinase Bmp3 of Botrytis cinerea is required for normal saprotrophic growth, conidiation, plant surface sensing and host tissue colonization. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 173–184. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00383.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu H. W., Lee D. H., Florens L., Swanson S. K., Washburn M. P., Kwon S. H. (2014). Analysis of the heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) interactome in Drosophila. J. Proteomics 102, 137–147. 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siewers V., Viaud M., Jimenez-Teja D., Collado I. G., Gronover C. S., Pradier J. M., et al. (2005). Functional analysis of the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase gene bcbot1 of Botrytis cinerea indicates that botrydial is a strain-specific virulence factor. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 18, 602–612. 10.1094/MPMI-18-0602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana M., Sugimoto K., Nozaki M., Ueda J., Ohta T., Ohki M., et al. (2002). G9a histone methyltransferase plays a dominant role in euchromatic histone H3 lysine 9 methylation and is essential for early embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 16, 1779–1791. 10.1101/gad.989402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana M., Ueda J., Fukuda M., Takeda N., Ohta T., Iwanari H., et al. (2005). Histone methyltransferases G9a and GLP form heteromeric complexes and are both crucial for methylation of euchromatin at H3-K9. Genes Dev. 19, 815–826. 10.1101/gad.1284005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaru H., Selker E. U. (2001). A histone H3 methyltransferase controls DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. Nature 414, 277–283. 10.1038/35104508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaru H., Zhang X., McMillen D., Singh P. B., Nakayama J., Grewal S. I., et al. (2003). Trimethylated lysine 9 of histone H3 is a mark for DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. Nat. Genet. 34, 75–79. 10.1038/ng1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschiersch B., Hofmann A., Krauss V., Dorn R., Korge G., Reuter G. (1994). The protein encoded by the Drosophila position-effect variegation suppressor gene Su(var)3-9 combines domains of antagonistic regulators of homeotic gene complexes. EMBO J. 13, 3822–3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. M., Hopson R., Lin X., Cane D. E. (2009). Biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene botrydial in Botrytis cinerea. mechanism and stereochemistry of the enzymatic formation of presilphiperfolan-8 beta-ol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 8360–8361. 10.1021/ja9021649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Zhu W., Cheng J., Xie J., Jiang D., Li G., et al. (2016). Nox Complex signal and MAPK cascade pathway are cross-linked and essential for pathogenicity and conidiation of mycoparasite Coniothyrium minitans. Sci. Rep. 6:24325. 10.1038/srep24325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Zhu W. J., Cheng J. S., Xie J. T., Li B., Jiang D. H., et al. (2013). CmPEX6, a gene involved in peroxisome biogenesis, is essential for parasitism and conidiation by the sclerotial parasite Coniothyrium minitans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 3658–3666. 10.1128/AEM.00375-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom J. (1998). Chromatin structure: linking structure to function with histone H1. Curr. Biol. 8, R788–R791. 10.1016/S0960-9822(07)00500-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierda R. J., Rietveld I. M., Van Eggermond M. C., Belien J. A., Van Zwet E. W., Lindeman J. H., et al. (2015). Global histone H3 lysine 27 triple methylation levels are reduced in vessels with advanced atherosclerotic plaques. Life Sci. 129, 3–9. 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson B., Tudzynski B., Tudzynski P., Van Kan J. A. (2007). Botrytis cinerea: the cause of gray mould disease. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 561–580. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00417.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B., Jing C., Wilson J. R., Walker P. A., Vasisht N., Kelly G., et al. (2003). Structure and catalytic mechanism of the human histone methyltransferase SET7/9. Nature 421, 652–656. 10.1038/nature01378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q. Q., Chen Y. F., Ma Z. H. (2013). Involvement of BcVeA and BcVelB in regulating conidiation, pigmentation and virulence in Botrytis cinerea. Fungal Genet. Biol. 50, 63–71. 10.1016/j.fgb.2012.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yearim A., Gelfman S., Shayevitch R., Melcer S., Glaich O., Mallm J. P., et al. (2015). HP1 is involved in regulating the global impact of DNA methylation on alternative splicing. Cell Rep. 10, 1122–1134. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Tamaru H., Khan S. I., Horton J. R., Keefe L. J., Selker E. U., et al. (2002). Structure of the Neurospora SET domain protein DIM-5, a histone H3 lysine methyltransferase. Cell 111, 117–127. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00999-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Identification of BcDIM5 knockout and complemented transformants. (A) Principle of homologous recombination. (B) BcDIM5 knockout transformants identified by PCR. (C) BcDIM5 knockout transformants identified by RT-PCR. (D) BcDIM5 knockout transformants identified by Southern blot using HYG labeled with DIG as probe. (E) BcDIM5 complemented transformants identified by PCR.

Morphological comparison of the hyphal tips of BcDIM5 knockout and complemented transformants.

Virulence assay of BcDIM5 knockout and complemented transformants on detached soybean and tomato leaves. Virulence was evaluated based on the lesion diameter at 20°C for 48 h. (A) Virulence assay of BcDIM5 knockout and complemented transformants on detached soybean leaves. (B) Virulence was evaluated based on the lesion diameter on soybean leaves. (C) Virulence assay of BcDIM5 knockout and complemented transformants on tomato leaves. (D) Virulence was evaluated based on the lesion diameter on tomato leaves.

Expression level of genes in different phase. Forty-eight hour indicates the wild type strain B05.10 grown in PDA for 48 h, which is the hyphal growth stage; 156 h indicates the wild-type strain B05.10 grown in PDA for 156 h, which is the sclerotial development stage. IN indicates the wild-type strain B05.10 inoculated on A. thaliana leaves for 48 h, which is the infection stage.

Primers used in the study.