Abstract

The PPAR nuclear receptor family has acquired great relevance in the last decade, which is formed by three different isoforms (PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPAR ϒ). Those nuclear receptors are members of the steroid receptor superfamily which take part in essential metabolic and life-sustaining actions. Specifically, PPARG has been implicated in the regulation of processes concerning metabolism, inflammation, atherosclerosis, cell differentiation, and proliferation. Thus, a considerable amount of literature has emerged in the last ten years linking PPARG signalling with metabolic conditions such as obesity and diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and, more recently, cancer. This review paper, at crossroads of basic sciences, preclinical, and clinical data, intends to analyse the last research concerning PPARG signalling in obesity and cancer. Afterwards, possible links between four interrelated actors will be established: PPARG, the vitamin D/VDR system, obesity, and cancer, opening up the door to further investigation and new hypothesis in this fascinating area of research.

1. Introduction

There are three subtypes of PPARG, known as PPARG1, PPARG2, and PPARG3. It has been established that PPARG2 leads in potency as a transcription factor [1]. PPARG performs its functions mainly through PPARG1 and PPARG2 [2]. Moreover, it shares lots of additional features with its other counterparts. Concerning that, the parallelism found between the PPARG system and the vitamin D/vitamin D receptor (VD/VDR) system will be further explored later on.

In order to modulate gene expression, the PPAR NRs family, and specifically the PPARG, after binding with either natural or synthetic ligands, heterodimerizes with the Retinoid X Receptor (RXR) as vitamin D receptor (VDR) does.

Later on, the complex PPARG-RXR translocates to the nucleus in order to get attached to PPREs (PPAR Response Elements), genome nucleotides sequences wherefrom the PPARs will coordinate the expression or repression of some genes involved in metabolism, immunity, differentiation, or cellular proliferation, to cite some [3–6].

Once in the nucleus, several molecules known as corepressors and coactivators, which show histone modifying activities by themselves [7], bind the PPARG-RXR complex, showing some control over the genetic expression-repression interplay. Some known corepressors are SMRT or NCOR. When it comes to coactivators, we can mention p300/CRRB-binding protein (CBP) or SRC/p160 [8]. Importantly, differential recruitment of coactivators implies different gene expression patterns [9], wherefrom it can be deduced that the corepressors and coactivators comprise another gene expression regulatory point which is worth studying. PPREs are normally found in the promoter of those genes, which is regulated by PPARG activity [3]. The direct nucleotide sequences which PPARG-RXR will be bound to are known as DR-1 motifs (direct hexanucleotide repeats) of PPRE [8]. Some PPARG target genes are those codifying CD36, FABP4 (Fatty Acid Binding Protein 4), adiponectin, or the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α [10], all being genes involved in adipose tissue homeostasis. However, afar of its adipose functions PPARG is also vital for development of some important organs such as heart and the placenta [11].

2. The PPARG Physiology

PPARG behaves as a transcription factor, as many other nuclear receptors (NRs) do. Then, it modulates the expression and repression of a myriad of genes involved in metabolic homeostasis, regulating energy expenditure and storage [12, 13]. Some PPARG target genes are those codifying CD36, FABP4 (Fatty Acid Binding Protein 4), adiponectin, or the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α [10], all being genes involved in adipose tissue homeostasis. However, afar of its adipose functions PPARG is also vital for development of some important organs such as heart and the placenta [11]. Although most research on PPARG has been focused on its metabolic action, some of them are neurogenesis, osteogenesis, cancer, or cardiovascular disease [14]. Such pleiotropism of actions gives us a clue of the relevance of this transcription factor regarding health and disease. We know for instance that universal PPARG deletion and life are not compatible [11].

The considerable host of actions performed by PPARG can be compared to those of vitamin D and VDR [15], which has been implicated in neurologic disorders [16–18], autoimmune pathologies [19–21], cardiovascular disease [22], diabetes mellitus [23, 24], psoriasis [15] or infectious disease [25, 26], and, above all of what is mentioned, cancer [27, 28].

3. PPARG and Obesity

Much has been already written about PPARG signalling and its role in conditions such as obesity or diabetes. In obesity, PPARG orchestrates adipocyte maturation and differentiation, harmonising the role of many other players in that process [29]. Remarkably, it is the only known factor, which is completely necessary and sufficient for the adipocyte differentiation process to occur [11, 30]. This nuclear receptor acts, then, as a master regulator of adipogenesis.

In addition, it is widely known that PPARG has an important whole-body insulin-sensitizer role. For example, muscle-PPARG knocked-out mice are insulin resistant [31]. In adipose tissue, PPARG deletion leads to increases in bone mass, lipoatrophy, and insulin resistance (IR) [32]. In the same fashion, PPARG induces the proliferation of adipocytes progenitors into mature adipocytes and diminishes the osteoblasts population likewise [33].

The specific deletion of PPARG in liver conduces to IR and decrease of hepatic fat depots [34]. Even in macrophages, the presence of PPARG is important to keep adequate insulin sensitivity levels throughout the body [35, 36]. It is then easy to deduce that one of the main objectives of PPARG activity is the insulin sensitivity maintenance through different tissues.

Thiazolidinediones (TZD), a family of synthetic PPARG agonist widely used in diabetes treatment, show clear improvements in insulin sensitivity, enhanced adipocyte differentiation, reduction of leptin levels, and upregulation of adiponectin [37].

Contrary to the catabolic actions elicited by the PPARα and PPARδ, the PPARG is in charge of anabolic functions. As we have already addressed, adipogenesis and lipid storage are some of them. Illustrating this, a high-fat feeding augments PPARG expression while fasting diminishes it [38].

Remarkably, PPARG performs different functions in metabolically sick rodents and metabolically healthy ones. In disease, PPARG activation seems to improve metabolic parameters, but in the healthy population its downregulation shows antiobesity effects [39].

In the same way, more different effects have been described in metabolic health and disease regarding PPARG expression. For instance, in healthy subjects a high-fat meal greatly induced the expression of PPARG while the same high-fat feeding diminished PPARG expression in a group of morbidly obese patients [40].

In like manner, an indirect correlation between IR and PPARG expression, measured by glucose status, HOMA-IR index, and insulin levels, can be set in morbidly obese persons, whose visceral adipose and muscle tissues show less PPARG expression as IR increases [40].

During placentation and intrauterine development, the PPARG gene methylation patterns could be altered by maternal nutrition, which actually exerts long-term effects upon the receptor status in the offspring, as indicated very recently by Lendvai et al. [41]. This is preliminary evidence about the early programming of our lifelong metabolism set points through nutritional inputs, which could easily leave us susceptible to obesity and metabolic disease in later stages of life.

4. PPARG and Cancer

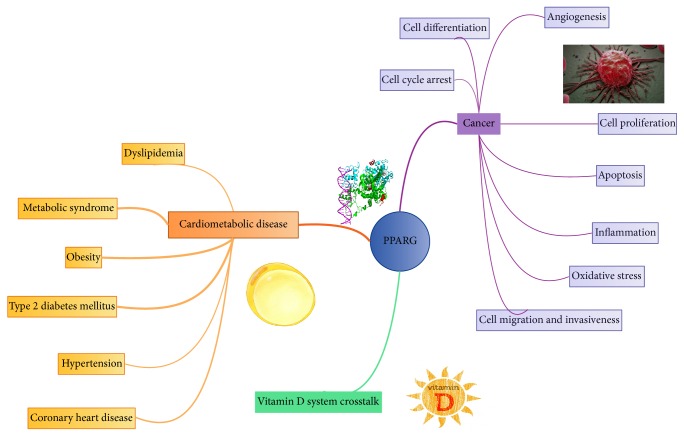

PPARG is highly expressed in lung, prostate, colorectal, bladder, and breast tumours [42]. Furthermore, we can find in the literature compelling evidence for PPARG having antineoplastic actions in colon, prostate, breast, and lung cancers [43, 44], which happen to be the most prevalent forms of cancer in occident (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PPARG actions: PPARG plays an important role in cardiometabolic disease and cancer. The noteworthy crosstalk between vitamin D system and PPARG is also considered. Arrow's width exemplifies the level of consistency found in the literature regarding each association in the mind picture.

Solid evidence backs up that epigenetic events frequently found in cancer can hamper nuclear receptors responsiveness toward their ligands. In that respect, increased levels of corepressor NCOR in prostate cancer can silence the expression of target genes and constitute a potential epigenetic lesion, which selectively distorts the actions of PPARG/PPARα [45].

In the same line, PPARG promoter methylation in colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is associated with poor prognosis [46]. This transcriptional silencing of PPARG is operated through HDAC1 (Histone Deacetylase 1), EZH2 (Enhancer of Zeste 2 Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Subunit), and MeCP2 (Methyl CpG Binding Protein 2) recruitment, leading to repressive chromatin states that eventually increase cell proliferation and invasive potential [46]. Correspondingly, APCmin/+ mice which have undergone PPARG genetic ablation demonstrate increased colon tumour growth [47].

In the literature, some mutations and variations in PPARG expression have been associated with cancer in our specie [48, 49]. Beyond that, its expression comprises an independent prognostic factor in CRC [50, 51].

Apart from epigenetics, we should not lose sight of the fact that metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, obesity, and inflammation, importantly interrelated conditions in which PPARG has modifying and regulatory actions, increase cancer risk [52–59], which adds weight to PPARG and cancer research (Figure 1).

There is some evidence linking PPARG agonist's actions to better cancer treatment responsiveness as well. PPARG agonist Rosiglitazone, in this phase II clinical trial, raised the radioiodine uptake in differentiated thyroid cancer [60].

IFN-β treated pancreatic cancer cells were more affected when Troglitazone was added to the therapy, showing synergistic effects between IFN-β and TGZ [61]. But it is necessary to be careful in some studies, in which PPARG agonist like Rosiglitazone acts as a great promoter of hydroxybutyl nitrosamine-induced urinary bladder cancers [62].

In the following paragraphs, we will review what we know about the specific molecular actions of PPARG in cancer biology. Cell cycle arrest, cell differentiation, angiogenesis, proliferation, invasiveness, migration capacity, apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress should be evaluated.

4.1. Cell Cycle Arrests

Some evidence suggests that PPARG and its agonists have the ability to interfere with the cellular cycle and then, likely, with malignancies development.

In renal cell carcinoma, Troglitazone (TGZ) was able to induce G2/M cell cycle arrest via activation of p38 MAPK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase) [63].

In human pancreatic cancer cells the same phenomenon is observed: PPARG is able to trigger cell cycle arrest of the malignant cells through activation by thiazolidinediones [64].

Through PPARG activation, its ligands increase the expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 [64, 65] and p27 [65–69], enhance the turnover of β-catenin, and downregulate the expression of cyclin D1 [70–74].

4.2. Differentiation

In vitro activation of PPARG by its ligands correlates with increased expression of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), E-cadherin, developmentally regulated GTP-binding protein 1 (DRG), alkaline phosphatase, or keratins, all of them being molecules expressed in well differentiated cells, opposing to the undifferentiated cell state commonly found in most cancers [48, 64, 75–77].

Tontonoz et al. gave us the first evidence about the effectiveness of PPARG ligands inducing differentiation in human cancer cells, concretely in liposarcoma cancer cells [75]. Again, in human liposarcoma, treatment with Troglitazone raised the level of differentiation of its cells [78].

More evidence that PPARG enhances terminal differentiation in cells is reviewed in papers of Grommes et al. and Koeffler, respectively [43, 44].

4.3. Angiogenesis

It is common knowledge that angiogenesis is a vital step in malignant development. The complex process by which new vessels are formed, angiogenesis, has been feverishly studied as a new possible target in cancer treatment.

In vitro and in vivo angiogenesis-modulating functions have been described for PPARG [79]. In spite of that, differential effects regarding angiogenesis have been observed for PPARG in vitro and in vivo, showing either pro- or antiangiogenic actions dependent on cell context [80–85]. PPARG agonist can also enhance VEGF expression in cancer cells, as some studies reveal [86, 87].

The mechanisms deciding whether PPARG will act as a proangiogenic factor or as an antiangiogenic one are still elusive to us, but we believe that cellular context and environment are likely the controllers of such process.

4.4. Proliferation

Antiproliferative actions are also attributed to PPARG and its ligands. TZD, for example, has shown antiproliferative effects [88, 89].

Modulation of PPARG can have differential effects on carcinogenesis depending on the cellular microenvironment [90]. Therefore, depending on the cellular environment PPARG can behave as a proliferative or antiproliferative factor, as happened with angiogenesis.

Tumour cells are frequently in shortage of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), a well-known ligand of the PPAR family, has been shown to reduce tumour proliferation in lung tumour cell cultures [91]. Along with that, DHA in breast cancer cells diminishes proliferation and increases apoptosis [92, 93].

In prostate cancer, PPARG ligand activation effect was assessed in a phase II clinical trial. The results showed a hampered cancer cell growth [94].

Eukaryotic initiation factor 2 is a target of inhibition for PPARG agonists (i.e., thiazolidinediones). Such factor inhibition, which is mediated in a PPARG-independent way, truncates the translation process [95].

In liposarcoma patients, treatment with Rosiglitazone increased the necessary time to double tumour volume in this clinical trial [96]. In other studies, however, Troglitazone (another member of the thiazolidinedione family) had low or no effects in prostate cancer [97] or breast or colorectal cancer [98, 99].

4.5. Apoptosis

The combined effect of an RXR agonist and Troglitazone curtailed gastric cancer cells proliferation in vitro by enhancing apoptotic mechanisms [100].

PPARG agonists increased the expression of PTEN [101–105], BAX, BAD [106, 107], and the turnover of the FLICE inhibitory protein (FLIP) [108, 109], known for its antiapoptotic role.

Conversely, PPARG agonists can inhibit BCL-XL and BCL-2 expression [107, 110], PI3K activity, and AKT phosphorylation [101, 111, 112] and restrain the activation of JUN N-terminal protein kinase [107]. It is worth mentioning that many of those actions were elicited in a PPARG-independent manner. The exact mechanisms by which these effects are performed are still unknown.

4.6. Inflammation

Nowadays, it is common knowledge in the scientific community that chronic inflammation promotes cancer. The milieu found in chronic inflammation acts as a facilitator for carcinogenesis and cancer development [52, 113]. This has been shown in colorectal, liver, bladder, lung, and gastric neoplasms [114, 115] and investigated in several more. The range of processes in which inflammation partakes in carcinogenesis goes from cell growth and survival, metastasis and cell invasion, treatment response, angiogenesis, and tumour immunity [115, 116].

There is evidence of PPARG having anti-inflammatory activity in several cell lines [117, 118]. In models of experimentally induced colitis PPARG expressed in macrophages is capable of inhibiting inflammation [119].

It is widely known that some PPAR ligands such as omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA have anti-inflammatory properties. Those and other natural and synthetic ligands could be used in the future as chemopreventive agents in a vast range of conditions linked to inflammation, that is, cancer [105, 120, 121].

Activation of PPARG by its ligands reduces cytokines such as TNFα and NF-κβ in monocytes, turning down the inflammatory milieu [120, 122].

The epigenetic process of sumoylation has been linked to PPARG transrepression of inflammation. After ligand activation, PPARG binds to a SUMO protein (Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier) and both join a nuclear corepressor complex, reducing the proinflammatory gene expression [123].

The NF-κβ transcription factor has repeatedly been associated with tumour development and thriving [52]. Interacting with this factor, PPARG inhibits the genesis of proinflammatory molecules such as IL-6, TNF, and MCP1 through transrepression [3, 117].

Again, a word of caution must be said due to the seemingly tumour-promoting effects of PPARG found sporadically [124–127]. Therefore, it seems as if the effects carried on by the cell depend of cell context and environment. Environment is, usually, at the helm of cellular functions.

4.7. Oxidative Stress

PPARG has demonstrated an antioxidant effect [128, 129]. SOD (Superoxide Dismutase) expression might well be regulated by PPAR because a PPRE is found in the Cu/Zn-SOD promoter [40].

IR found in diabetes mellitus and metabolic disease is certainly correlated with increased oxidative stress, which eventually could lead to an increased risk of cancer through nongenomic carcinogenesis [130–133].

In macrophages, PPARG mediates some notable abilities: uptake and reverse transport of cholesterol, macrophage subtype specification (enhancing the M2 macrophage phenotype, which is associated with higher insulin sensitivity and lower inflammation levels), and anti-inflammation properties [36, 134, 135].

Postprandial hypertriglyceridemia is associated with lower PPARG expression in metabolic syndrome patients while in healthy subjects the same “insult” leads to overexpression of PPARG [136]. We could hypothesize that since the PPARG system is injured in the metabolically ill patients, after an oxidative stress insult (a high-fat feeding), it cannot respond, leaving us more susceptible to oxidative actions and its consequences (hypothesis coined as “nuclear receptor exhaustion theory”). In the healthy group, the PPARG would perfectly be capable of managing the lipid storage and would act as an oxidative stress buffer.

4.8. Cell Migration and Invasiveness

Less evidence is available with respect to invasiveness and PPARG. However, we should pay attention to some preliminary data.

The PPARG gene modulates the invasion of cytotrophoblast into uterine tissue, which could be a novel indicator of some invasion-related function of PPARG [137].

Going further, this study by Yoshizumi et al. showed how PPARG ligand thiazolidinedione (TZD) is able to inhibit growth and metastasis of HT-29 human colon cancer cells, via the induction of cell differentiation. The use of the TZD drives to G1 arrest, in association with a great increase in p21Waf-1, Drg-1, and E-cadherin expression [77].

Paradoxically, molecules with PPARG antagonist actions are able to inhibit invasiveness and proliferation of some cancer cell lines [26, 138–140]. Again, one nuclear receptor can exert one or just the opposite function depending on the cellular environment and ligand exposure.

5. Connecting the Dots: PPARG, Vitamin D System, Obesity, and Cancer

Often in biology and medicine research, we tend to focus on the individualities of separated molecules or molecule systems in order to explain their functions, forgetting the intermolecular communication, which is ever-present in every biological system. More frequent than not, that separateness gives us a rather limited perspective of the matter at hand. For instance, the interconnectedness of biology systems and the emerging properties of such interconnectedness should be further examined and taken into account.

The crosstalk between different NRs, the “dance” and messages they give one another, is recently becoming an exciting new area which will be explored. This is the case of the VDR/VD and the PPARG system, in which both have been shown to be involved in some relationship we do not utterly understand yet.

5.1. PPARG and VDR/VD System: Commonalities in Cancer

Noteworthy, great parallelism exists between PPARG and the VDR/VD system regarding its protective role in carcinogenesis. There are a vast number of studies describing the anticancer properties of vitamin D. The majority of them are brilliantly analysed in this review by Feldman et al. [28].

Vitamin D has been extensively associated with anti-inflammatory actions [141–143], apoptotic mechanisms [144–150], antiproliferative functions [151–159], prodifferentiation effects [160–166], antiangiogenic properties [167–171], a potential role-managing invasion and metastasis [172–184], microRNA modulation [185–189], and even some role in the Hedgehog signalling pathway modulation [190]. Remarkably, most of those actions have been attributed to PPARG signalling in a somewhat lesser extent, as reviewed in this work. Such similarity and overlap in anticancer actions are worth studying.

Moreover, there is enough evidence to assert that epigenetic events can influence both PPARG and VDR/VD systems behaviour.

In this study, Fujiki et al. showed that in a diabetic mouse model PPARG promoter methylation levels are higher than those of the control mice [191], along with the possibility of methylation reversal when the animals were exposed to 5AZA (5′-aza-cytidine). At least three messages can be drawn from this study: (1) the PPARG system is susceptible to epigenetic regulation, (2) diabetes and other metabolic conditions could alter the PPARG epigenetic landscape and then disrupt its proper functioning, and (3) this disruption can be reversed by drug-induced changes or, likely, by lifestyle changes.

The vitamin D system is likewise susceptible to epigenetic regulation [192–195] and, interestingly, in cancer this epigenetic repression of the vitamin D system is almost always present [196–204], which compellingly leaves the door opened to the possibility of the same phenomena happening in the PPARG system.

In fact, PPARG promoter hypermethylation is a prognostic factor of adverse outcome in colorectal cancer [46, 205]. Higher levels of PPARG promoter methylation were found in advanced tumour stages while earlier stages showed lower methylation levels. This suggests that as happens with vitamin D, advanced cancer stages can epigenetically repress PPARG expression and then nullify its antineoplastic actions.

5.2. The PPARG/VDR Crosstalk: What an Interesting Conversation!

Some studies have clearly shown the existence of some communication between PPARG and VD/VDR. Interestingly, potent VDRE (Vitamin D Response Elements) have been discovered in human PPARδ promoter, which opens the door to VDR/VD influence over the PPAR system [206]. In the opposite direction, some studies have demonstrated the ability of PPARG to bind VDR and inhibit vitamin D-mediated transactivation [207]. This data might be an indicator of bidirectional or reciprocal actions of both systems influencing each other, which have deep implications and introduce new and interesting questions to ponder upon.

Even between PPAR subtypes some modulation of expression have been found: PPARδ could repress PPARα and PPARG gene expression [208], illustrating the complexity of PPAR system regulation.

In the adipocyte cell, the VD/VDR system has shown anti-PPARG activity, inhibiting its expression and then adipogenesis [209, 210], which is contradictory with the commonly found proadipogenesis effects of vitamin D [211], at least in human. The factors leading to either pro- or antiadipogenesis effects are completely uncharted.

In melanoma cell lines, administration of calcitriol and several PPAR ligands modified the expression of both PPARG and VDR, demonstrating again this intriguing connection [212]. Sertznig et al. conclude in this article that calcitriol and some PPAR ligands can inhibit proliferation of the human melanoma cell line MeWo [213].

5.3. PPARG and VD/VDR System: Metabolic Commonalities

We are about to discuss the metabolic effects of vitamin D and their analogy with those of PPARG, establishing again the parallelism.

As contradictory as it seems, VDR or CYP27B1 knocked-out mice show great fat mass loss [211] while obesity in humans is commonly associated with poor vitamin D plasmatic levels [214]. Actually, an indirect relationship between Body Mass Index (BMI) and 25OHD3 has been amply described in the literature [215].

In addition, low plasmatic vitamin D levels are associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) independently of BMI [24] and with hypertension, dyslipidemia (DLP), and metabolic syndrome (MS) [216, 217]. Besides, vitamin D deficiency predisposes to diabetes in animal models, while its supplementation prevents the disease [214]. Concerning PPARG, we have extensively discussed before in the review its orchestrating actions regarding adipogenesis and adipocyte metabolism. Both calcitriol (the active form of vitamin D) and PPARG seem to oppose metabolic homeostasis disruption.

Another paradoxical event is found in the fact that in humans calcitriol enhances adipogenesis while in mice the same hormone diminishes it via downregulation of C/EBPβ mRNA and upregulation of CBFA2T1 (a corepressor) [218, 219]. With reference to PPARG, it enhances adipogenesis [10].

In human subcutaneous preadipocytes, calcitriol elicits actions impressively similar to those of PPARG in adipocyte maturation and differentiation. For instance, calcitriol is able to increase the expression of the enzyme Fatty Acid Synthase (FASN) increasing lipogenesis in like manner as PPARG [210].

The storage capacity theory introduces the idea that lipid storage capacity and the ability of PPARG to manage the processes leading to lipid storage are limited. As to that, when the organism reaches a lipid level threshold lipotoxicity shows up, PPARG is no more capable of lipid handling, and the harmful hormonal environment of obesity starts to spread through the organism [220].

Transferring the same concept of “nuclear receptor exhaustion” to VD/VDR anticancer actions we could establish a parallelism. It has shown that the VD/VDR is epigenetically downregulated in late cancer stages but overexpressed or normally expressed in early stages [221, 222]. As the aforementioned studies show, in those later stages epigenetic downregulation of the VD system molecules occurs, leaving it unable to exert its antineoplastic functions properly. Is obesity, as cancer does with vitamin D, acting as a negative epigenetic driver when it comes to PPARG signalling? That could answer why in most morbidly obese patients expression of PPARG is greatly lower in comparison to healthy subjects.

Accordingly, PPARG1 and PPARG2 expression in visceral adipose tissue (VAT) from morbidly obese (MO) subjects is significantly downregulated when compared to metabolically healthy subjects [223]. Not only that, in insulin resistant MO subjects PPARG expression is even lower [220] compared with noninsulin resistant MO patients, whichever interestingly correlates with the lower vitamin D levels found in MO with IR compared to their insulin sensitive counterparts [24]. Somehow, the metabolic impairment caused by insulin resistance is able to deteriorate both PPARG and VD/VDR system. The underlying mechanism behind this deterioration should be further studied.

A disrupted VDR/VD system leads mice to loss of fat deposits and great increase of energy expenditure. In relation to that, VDR−/− mice increase the expression of UCP1 (uncoupling protein 1 or Thermogenin) twenty-five-fold [211], with the consequent energy consumption. Is vitamin D, along with PPARG, an energy-conserving and metabolic homeostasis-maintaining hormone?

However, adipose tissue is not the only one affected by disruption of the VD system. A shortage of calcitriol in rats was related with increased skeletal muscle ubiquitination and loss of total muscle mass [224]. On the PPARG side, its activation through TZD in growing pigs increased muscle fiber oxidative capacity independently of fiber type [225]. Overexpression of PPARδ in mice almost doubles the animal endurance and exercise capacity [226]. We should not lose sight of the important role the muscle has in obesity and metabolic disease pathogenesis, being a potential target for calcitriol and PPAR modulating actions.

Taken all data together, the vitamin D system seems to team up with PPARG in order to maintain proper metabolic homeostasis. Notwithstanding, in some occasions this love relationship breaks apart and both partners seem to bother one another in ways that we utterly ignore but, likely, have something to do with epigenetic regulation.

6. Conclusions

The PPARG transcription factor has been classically associated with metabolic homeostasis and lipid storage functions. Recently, newfound anticancer actions are assigned to this nuclear receptor.

However, its anticancer actions are not always consistent; in some studies some oncogenic effects have been described. We believe that cellular environment is the guiding factor behind PPARG actions and cells are controlled “from outside in.” In alignment with this, the PPARG and other nuclear receptors would only be “cellular effectors,” carriers of outside messages of health or disease.

When a “disease threshold” is reached, in either obesity or cancer, PPARG and VDR expression, respectively, diminishes. However, in early stages of those diseases, the expression of those nuclear receptors is higher than normal. Derived from these observations, we have coined the so-called “nuclear receptor exhaustion theory,” by which, in an early disease stage, nuclear receptors PPARG and VDR counterbalance the harmful effects that obesity and cancer exert upon the organism, their expression being high. However, sadly, if disease progresses, it generates epigenetic silencing mechanisms upon both transcription factors, whose expression decreases radically. This silencing leaves us increasingly susceptible to disease. The positive side is that through drugs or, better yet, lifestyle changes reversal of epigenetic changes is possible.

There is an exciting function overlap between PPARG and VDR/VD system, both of which wield oncoprotective and metabolic actions. Actually, parallel metabolic and anticancer actions are described in the literature, suggesting that they team up to keep at bay those diseases. Maybe the detailed study of this overlap could give us clues in respect to the molecular pathogenesis of important conditions as metabolic disease and cancer. Further study in this new area is necessary to elucidate those questions.

Obesity, a first-order problem in our society, is linked with increased risk of cancer incidence and progression. The debatable factors behind this risk are an increment in oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, poorer vitamin D status, hormone misbalance, and, arguably, PPARG silencing through unknown mechanisms. As we know, PPARG and the vitamin D system play conjunctly a yet-to-elucidate role in cancer, so it is not surprising at all that their hypothetical epigenetic repression in obesity could be another mechanism linking this metabolic disorder to malignancies.

It has been shown, both in vitro and in vitro, that the tumours are capable of epigenetically silencing both the vitamin D and the PPARG system. This silencing could lead to the deterioration of their anticancer and metabolic actions.

Finally, a worse known crosstalk between the two NRs exists. Its usefulness, purpose, and message are (almost) utterly unexplored to us and should be studied more diligently. The interrelation, reciprocity, and interdependence of all four actors examined here might be the starting point of new fascinating research linking epigenetic signalling and two of the most hurtful diseases of our time (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The four players: this figure shows the interrelation between the four players: obesity, cancer, vitamin D system, and PPARG. Red arrow: harmful effects, which contribute to disease. Green arrow:positive effects, which contribute to health. Disease perpetuates itself damaging both nuclear receptors. Arrow's width is in proportion with the strength and consistency of each association found in the literature. Dashed line: yet-to-be determined, preliminary, or hypothetical effects. Continuous line: in vitro/in vivo demonstrated effects. Right box: in green, actions mainly attributed to vitamin D, and in purple, actions classically attributed to PPARG. However, it is known that both agents exert every action illustrated in this box, in a higher or lower extent.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by “Centros de Investigación En Red” (CIBER, CB06/03/0018), the “Instituto de Salud Carlos III” (ISCIII), and grants from ISCIII (PI11/01661) and from Consejería de Innovacion, Ciencia y Empresa de la Junta de Andalucía (PI11-CTS-8181) and cofinanced by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER). M. Macías-González was recipient of the Nicolas Monarde program from the Servicio Andaluz de Salud, Junta de Andalucía, Spain (C0029-2014).

Additional Points

Design is literature review across preclinical studies, descriptive studies, analytic studies, and reference lists of selected studies. The author focused mainly on systematic and narrative reviews. Data sources are medline (Pubmed), Jábega 2.0 (Málaga University Search Engine Software), Gerión search engine, and screening of citations and references. Regarding eligibility criteria, we focused on papers published in magazines considered to be in the first impact factor quartile without restrictions regarding publishing date. Keywords are PPARG; Obesity; Transcription factor; Vitamin D; Calcitriol; Vitamin D Receptor; Epigenetics; Nuclear Receptor; Cancer; Methylation.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

References

- 1.Feige J. N., Gelman L., Michalik L., Desvergne B., Wahli W. From molecular action to physiological outputs: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are nuclear receptors at the crossroads of key cellular functions. Progress in Lipid Research. 2006;45(2):120–159. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu Y., Qi C., Korenberg J. R., et al. Structural organization of mouse peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (mPPARγ) gene: alternative promoter use and different splicing yield two mPPARγ isoforms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(17):7921–7925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters J. M., Shah Y. M., Gonzalez F. J. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2012;12(3):181–195. doi: 10.1038/nrc3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogue A., Spire C., Brun M., Claude N., Guillouzo A. Gene expression changes induced by PPAR γ agonists in animal and human liver. PPAR Research. 2010;2010:16. doi: 10.1155/2010/325183.325183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willson T. M., Brown P. J., Sternbach D. D., Henke B. R. The PPARs: from orphan receptors to drug discovery. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2000;43(4):527–550. doi: 10.1021/jm990554g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schupp M., Lazar M. A. Endogenous ligands for nuclear receptors: digging deeper. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(52):40409–40415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.r110.182451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu S. C., Zhang Y. Minireview: role of protein methylation and demethylation in nuclear hormone signaling. Molecular Endocrinology. 2009;23(9):1323–1334. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugii S., Evans R. M. Epigenetic codes of PPARγ in metabolic disease. FEBS Letters. 2011;585(13):2121–2128. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kodera Y., Takeyama K.-I., Murayama A., Suzawa M., Masuhiro Y., Kato S. Ligand type-specific interactions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ with transcriptional coactivators. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(43):33201–33204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.c000517200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tontonoz P., Spiegelman B. M. Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARγ . Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2008;77:289–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061307.091829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barak Y., Nelson M. C., Ong E. S., et al. PPARγ is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Molecular Cell. 1999;4(4):585–595. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger J., Moller D. E. The mechanisms of action of PPARs. Annual Review of Medicine. 2002;53(1):409–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boitier E., Gautier J.-C., Roberts R. Advances in understanding the regulation of apoptosis and mitosis by peroxisome-proliferator activated receptors in pre-clinical models: relevance for human health and disease. Comparative Hepatology. 2003;2, article 3 doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J.-H., Song J., Park K. W. The multifaceted factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) in metabolism, immunity, and cancer. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2015;38(3):302–312. doi: 10.1007/s12272-015-0559-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagpal S., Na S., Rathnachalam R. Noncalcemic actions of vitamin D receptor ligands. Endocrine Reviews. 2005;26(5):662–687. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groves N. J., McGrath J. J., Burne T. H. J. Vitamin D as a neurosteroid affecting the developing and adult brain. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2014;34:117–141. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071813-105557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.London J. W. Low Vitamin D is linked to faster cognitive decline in older adults. The British Medical Journal. 2015;351 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4916.h4916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy M. Study supports link between low vitamin D and dementia risk. BMJ. 2014;349 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5049.g5049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koizumi T., Nakao Y., Matsui T., et al. Effects of corticosteroid and 1,24R-dihydroxy-vitamin D3 administration on lymphoproliferation and autoimmune disease in MRL/MP-lpr/lpr mice. International Archives of Allergy and Applied Immunology. 1985;77(4):396–404. doi: 10.1159/000233815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregori S., Giarratana N., Smiroldo S., Uskokovic M., Adorini L. A 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 analog enhances regulatory T-cells and arrests autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2002;51(5):1367–1374. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuji M., Fujii K., Nakano T., Nishii Y. 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits Type II collagen-induced arthritis in rats. FEBS Letters. 1994;337(3):248–250. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manousopoulou A., Al-Daghri N. M., Garbis S. D., Chrousos G. P. Vitamin D and cardiovascular risk among adults with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015;45(10):1113–1126. doi: 10.1111/eci.12510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boucher B. J., John W. G., Noonan K. Hypovitaminosis D is associated with insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;80(6):1666–1667. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clemente-Postigo M., Muñoz-Garach A., Serrano M., et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and adipose tissue vitamin D receptor gene expression: relationship with obesity and type 2 diabetes. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2015;100(4):E591–E595. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bakdash G., van Capel T. M. M., Mason L. M. K., Kapsenberg M. L., de Jong E. C. Vitamin D3 metabolite calcidiol primes human dendritic cells to promote the development of immunomodulatory IL-10-producing T cells. Vaccine. 2014;32(47):6294–6302. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi K. Influence of bacteria on epigenetic gene control. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2014;71(6):1045–1054. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1487-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma Y., Johnson C. S., Trump D. L. Mechanistic Insights of Vitamin D Anticancer Effects. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feldman D., Krishnan A. V., Swami S., Giovannucci E., Feldman B. J. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2014;14(5):342–357. doi: 10.1038/nrc3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cristancho A. G., Lazar M. A. Forming functional fat: a growing understanding of adipocyte differentiation. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2011;12(11):722–734. doi: 10.1038/nrm3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosen E. D., Spiegelman B. M. Molecular regulation of adipogenesis. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2000;16:145–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hevener A. L., He W., Barak Y., et al. Muscle-specific Pparg deletion causes insulin resistance. Nature Medicine. 2003;9(12):1491–1497. doi: 10.1038/nm956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang F., Mullican S. E., DiSpirito J. R., Peed L. C., Lazar M. A. Lipoatrophy and severe metabolic disturbance in mice with fat-specific deletion of PPARγ . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(46):18656–18661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314863110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Won Park K., Halperin D. S., Tontonoz P. Before they were fat: adipocyte progenitors. Cell Metabolism. 2008;8(6):454–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsusue K., Haluzik M., Lambert G., et al. Liver-specific disruption of PPARγ in leptin-deficient mice improves fatty liver but aggravates diabetic phenotypes. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;111(5):737–747. doi: 10.1172/jci200317223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hevener A. L., Olefsky J. M., Reichart D., et al. Macrophage PPARγ is required for normal skeletal muscle and hepatic insulin sensitivity and full antidiabetic effects of thiazolidinediones. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117(6):1658–1669. doi: 10.1172/jci31561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Odegaard J. I., Ricardo-Gonzalez R. R., Goforth M. H., et al. Macrophage-specific PPARγ controls alternative activation and improves insulin resistance. Nature. 2007;447(7148):1116–1120. doi: 10.1038/nature05894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ament Z., Masoodi M., Griffin J. L. Applications of metabolomics for understanding the action of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in diabetes, obesity and cancer. Genome Medicine. 2012;4(4, article 32) doi: 10.1186/gm331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vidal-Puig A., Jimenez-Liñan M., Lowell B. B., et al. Regulation of PPAR γ gene expression by nutrition and obesity in rodents. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;97(11):2553–2561. doi: 10.1172/jci118703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imam M. U., Ismail M., Ithnin H., Tubesha Z., Omar A. R. Effects of germinated brown rice and its bioactive compounds on the expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma gene. Nutrients. 2013;5(2):468–477. doi: 10.3390/nu5020468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia-Fuentes E., Murri M., Garrido-Sanchez L., et al. PPARγ expression after a high-fat meal is associated with plasma superoxide dismutase activity in morbidly obese persons. Obesity. 2010;18(5):952–958. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lendvai Á., Deutsch M. J., Plösch T., Ensenauer R. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors under epigenetic control in placental metabolism and fetal development. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism. 2016;310(10):E797–E810. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00372.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell M. J., Carlberg C., Koeffler H. P. A role for the PPARγ in cancer therapy. PPAR Research. 2008;2008:17. doi: 10.1155/2008/314974.314974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grommes C., Landreth G. E., Heneka M. T. Antineoplastic effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists. Lancet Oncology. 2004;5(7):419–429. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(04)01509-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koeffler H. P. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and cancers. Clinical Cancer Research. 2003;9(1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Battaglia S., Maguire O., Thorne J. L., et al. Elevated NCOR1 disrupts PPARα/γ signaling in prostate cancer and forms a targetable epigenetic lesion. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(9):1650–1660. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pancione M., Sabatino L., Fucci A., et al. Epigenetic silencing of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ is a biomarker for colorectal cancer progression and adverse patients' outcome. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014229.e14229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 47.McAlpine C. A., Barak Y., Matise I., Cormier R. T. Intestinal-specific PPARγ deficiency enhances tumorigenesis in ApcMin/+ mice. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;119(10):2339–2346. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarraf P., Mueller E., Smith W. M., et al. Loss-of-function mutations in PPARγ associated with human colon cancer. Molecular Cell. 1999;3(6):799–804. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)80012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Capaccio D., Ciccodicola A., Sabatino L., et al. A novel germline mutation in Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ gene associated with large intestine polyp formation and dyslipidemia. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-Molecular Basis of Disease. 2010;1802(6):572–581. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pancione M., Forte N., Sabatino L., et al. Reduced β-catenin and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ expression levels are associated with colorectal cancer metastatic progression: correlation with tumor-associated macrophages, cyclooxygenase 2, and patient outcome. Human Pathology. 2009;40(5):714–725. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ogino S., Shima K., Baba Y., et al. Colorectal cancer expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARG, PPARγ) is associated with good prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1242–1250. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mantovani A., Allavena P., Sica A., Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsugane S., Inoue M. Insulin resistance and cancer: epidemiological evidence. Cancer Science. 2010;101(5):1073–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bilic I. Obesity and cancer. Periodicum Biologorum. 2014;116(4):355–359. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khandekar M. J., Cohen P., Spiegelman B. M. Molecular mechanisms of cancer development in obesity. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2011;11(12):886–895. doi: 10.1038/nrc3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Renehan A. G. Adipose Tissue in Health and Disease. 2010. Obesity and cancer; pp. 369–384. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Calle E. E., Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2004;4(8):579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wolin K. Y., Carson K., Colditz G. A. Obesity and cancer. Oncologist. 2010;15(6):556–565. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gonzá Lez Svatetz C. A., Goday Arnó A. Obesidad y cáncer. Medicina Clínica. 2015;145(1):24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2014.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kebebew E., Peng M., Reiff E., et al. A phase II trial of rosiglitazone in patients with thyroglobulin-positive and radioiodine-negative differentiated thyroid cancer. Surgery. 2006;140(6):960–967. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vitale G., Zappavigna S., Marra M., et al. The PPAR-γ agonist troglitazone antagonizes survival pathways induced by STAT-3 in recombinant interferon-β treated pancreatic cancer cells. Biotechnology Advances. 2012;30(1):169–184. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lubet R. A., Fischer S. M., Steele V. E., Juliana M. M., Desmond R., Grubbs C. J. Rosiglitazone, a PPAR γ agonist: potent promoter of hydroxybutyl(butyl)nitrosamine-induced urinary bladder cancers. International Journal of Cancer. 2008;123(10):2254–2259. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fujita M., Yagami T., Fujio M., et al. Cytotoxicity of troglitazone through PPARγ-independent pathway and p38 MAPK pathway in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Letters. 2011;312(2):219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Elnemr A., Ohta T., Iwata K., et al. PPARgamma ligand (thiazolidinedione) induces growth arrest and differentiation markers of human pancreatic cancer cells. International Journal of Oncology. 2000;17(6):1157–1164. doi: 10.3892/ijo.17.6.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koga H., Sakisaka S., Harada M., et al. Involvement of p21WAF1/Cip1, p27Kip1, and p18INK4c in troglitazone-induced cell-cycle arrest in human hepatoma cell lines. Hepatology. 2001;33(5):1087–1097. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen F., Harrison L. E. Ciglitazone-induced cellular anti-proliferation increases p27 kip1 protein levels through both increased transcriptional activity and inhibition of proteasome degradation. Cellular Signalling. 2005;17(7):809–816. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen F., Kim E., Wang C.-C., Harrison L. E. Ciglitazone-induced p27 gene transcriptional activity is mediated through Sp1 and is negatively regulated by the MAPK signaling pathway. Cellular Signalling. 2005;17(12):1572–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Motomura W., Okumura T., Takahashi N., Obara T., Kohgo Y. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma by troglitazone inhibits cell growth through the increase of p27KiP1 in human. Pancreatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Research. 2000;60(19):5558–5564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Itami A., Watanabe G., Shimada Y., et al. Ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ inhibit growth of pancreatic cancers both in vitro and in vivo. International Journal of Cancer. 2001;94(3):370–376. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lapillonne H., Konopleva M., Tsao T., et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma by a novel synthetic triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid induces growth arrest and apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2003;63(18):5926–5939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang J.-W., Shiau C.-W., Yang Y.-T., et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-independent ablation of cyclin D1 by thiazolidinediones and their derivatives in breast cancer cells. Molecular Pharmacology. 2005;67(4):1342–1348. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.007732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qin C., Burghardt R., Smith R., Wormke M., Stewart J., Safe S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists induce proteasome-dependent degradation of cyclin D1 and estrogen receptor α in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2003;63(5):958–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang C., Fu M., D'Amico M., et al. Inhibition of cellular proliferation through IκB kinase-independent and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-dependent repression of cyclin D1. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2001;21(9):3057–3070. doi: 10.1128/mcb.21.9.3057-3070.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yin F., Wakino S., Liu Z., et al. Troglitazone inhibits growth of MCF-7 breast carcinoma cells by targeting G1 cell cycle regulators. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2001;286(5):916–922. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tontonoz P., Singer S., Forman B. M., et al. Terminal differentiation of human liposarcoma cells induced by ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and the retinoid X receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(1):237–241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gupta R. A., Brockman J. A., Sarraf P., Willson T. M., DuBois R. N. Target genes of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ in colorectal cancer cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(32):29681–29687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m103779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yoshizumi T., Ohta T., Ninomiya I., et al. Thiazolidinedione, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligand, inhibits growth and metastasis of HT-29 human colon cancer cells through differentiation-promoting effects. International Journal of Oncology. 2004;25(3):631–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Demetri G. D., Fletcher C. D. M., Mueller E., et al. Induction of solid tumor differentiation by the peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor-γ ligand troglitazone in patients with liposarcoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(7):3951–3956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Margeli A., Kouraklis G., Theocharis S. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) ligands and angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2003;6(3):165–169. doi: 10.1023/b:agen.0000021377.13669.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Biscetti F., Gaetani E., Flex A., et al. Selective activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)α and PPARγ induces neoangiogenesis through a vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent mechanism. Diabetes. 2008;57(5):1394–1404. doi: 10.2337/db07-0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chu K., Lee S.-T., Koo J.-S., et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ-agonist, rosiglitazone, promotes angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Research. 2006;1093(1):208–218. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huang P.-H., Sata M., Nishimatsu H., Sumi M., Hirata Y., Nagai R. Pioglitazone ameliorates endothelial dysfunction and restores ischemia-induced angiogenesis in diabetic mice. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2008;62(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bishop-Bailey D., Hla T. Endothelial cell apoptosis induced by the peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor (PPAR) ligand 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(24):17042–17048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xin X., Yang S., Kowalski J., Gerritsen M. E. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands are potent inhibitors of angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo . The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(13):9116–9121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.9116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Margeli A., Kouraklis G., Theocharis S. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) ligands and angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2003;6(3):165–169. doi: 10.1023/B:AGEN.0000021377.13669.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fauconnet S., Lascombe I., Chabannes E., et al. Differential regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in bladder cancer cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(26):23534–23543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chintalgattu V., Harris G. S., Akula S. M., Katwa L. C. PPAR-γ agonists induce the expression of VEGF and its receptors in cultured cardiac myofibroblasts. Cardiovascular Research. 2007;74(1):140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bambury R. M., Iyer G., Rosenberg J. E. Specific PPAR gamma agonists may have different effects on cancer incidence. Annals of Oncology. 2013;24(3, article 854) doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Terrasi M., Bazan V., Caruso S., et al. Effects of PPARγ agonists on the expression of leptin and vascular endothelial growth factor in breast cancer cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2013;228(6):1368–1374. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Elrod H. A., Sun S.-Y. PPARγ and apoptosis in cancer. PPAR Research. 2008;2008:12. doi: 10.1155/2008/704165.704165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Trombetta A., Maggiora M., Martinasso G., Cotogni P., Canuto R. A., Muzio G. Arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acids reduce the growth of A549 human lung-tumor cells increasing lipid peroxidation and PPARs. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2007;165(3):239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Edwards I. J., Berquin I. M., Sun H., et al. Differential effects of delivery of omega-3 fatty acids to human cancer cells by low-density lipoproteins versus albumin. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(24):8275–8283. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sun H., Berquin I. M., Owens R. T., O'Flaherty J. T., Edwards I. J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-mediated up-regulation of syndecan-1 by n-3 fatty acids promotes apoptosis of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2008;68(8):2912–2919. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-07-2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mueller E., Smith M., Sarraf P., et al. Effects of ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ in human prostate cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(20):10990–10995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180329197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Palakurthi S. S., Aktas H., Grubissich L. M., Mortensen R. M., Halperin J. A. Anticancer effects of thiazolidinediones are independent of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and mediated by inhibition of translation initiation. Cancer Research. 2001;61(16):6213–6218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Debrock G., Vanhentenrijk V., Sciot R., Debiec-Rychter M., Oyen R., Van Oosterom A. A phase II trial with rosiglitazone in liposarcoma patients. British Journal of Cancer. 2003;89(8):1409–1412. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Smith M. R., Manola J., Kaufman D. S., et al. Rosiglitazone versus placebo for men with prostate carcinoma and a rising serum prostate-specific antigen level after radical prostatectomy and/or radiation therapy. Cancer. 2004;101(7):1569–1574. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Burstein H. J., Demetri G. D., Mueller E., Sarraf P., Spiegelman B. M., Winer E. P. Use of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) γ ligand troglitazone as treatment for refractory breast cancer: a phase II study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2003;79(3):391–397. doi: 10.1023/a:1024038127156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kulke M. H., Demetri G. D., Sharpless N. E., et al. A phase II study of troglitazone, an activator of the PPARγ receptor, in patients with chemotherapy-resistant metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Journal. 2002;8(5):395–399. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200209000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu Y., Zhu Z.-A., Zhang S.-N., et al. Combinational effect of PPARγ agonist and RXR agonist on the growth of SGC7901 gastric carcinoma cells in vitro. Tumor Biology. 2013;34(4):2409–2418. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0791-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Farrow B., Evers B. M. Activation of PPARγ increases PTEN expression in pancreatic cancer cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;301(1):50–53. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02983-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang W., Wu N., Li Z., Wang L., Jin J., Zha X.-L. PPARγ activator rosiglitazone inhibits cell migration via upregulation of PTEN in human hepatocarcinoma cell line BEL-7404. Cancer Biology and Therapy. 2006;5(8):1008–1014. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.8.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Teresi R. E., Shaiu C.-W., Chen C.-S., Chatterjee V. K., Waite K. A., Eng C. Increased PTEN expression due to transcriptional activation of PPARγ by Lovastatin and Rosiglitazone. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;118(10):2390–2398. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lee S. Y., Hur G. Y., Jung K. H., et al. PPAR-γ agonist increase gefitinib's antitumor activity through PTEN expression. Lung Cancer. 2006;51(3):297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Patel L., Pass I., Coxon P., Downes C. P., Smith S. A., Macphee C. H. Tumor suppressor and anti-inflammatory actions of PPARγ agonists are mediated via upregulation of PTEN. Current Biology. 2001;11(10):764–768. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zander T., Kraus J. A., Grommes C., et al. Induction of apoptosis in human and rat glioma by agonists of the nuclear receptor PPARγ . Journal of Neurochemistry. 2002;81(5):1052–1060. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bae M.-A., Song B. J. Critical role of c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase activation in troglitazone-induced apoptosis of human HepG2 hepatoma cells. Molecular Pharmacology. 2003;63(2):401–408. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kim Y., Suh N., Sporn M., Reed J. C. An inducible pathway for degradation of FLIP protein sensitizes tumor cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(25):22320–22329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202458200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schultze K., Böck B., Eckert A., et al. Troglitazone sensitizes tumor cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis via down-regulation of FLIP and survivin. Apoptosis. 2006;11(9):1503–1512. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-8896-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shiau C.-W., Yang C.-C., Kulp S. K., et al. Thiazolidenediones mediate apoptosis in prostate cancer cells in part through inhibition of Bcl-xL/Bcl-2 functions independently of PPARγ . Cancer Research. 2005;65(4):1561–1569. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kim K. Y., Kim S. S., Cheon H. G. Differential anti-proliferative actions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonists in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2006;72(5):530–540. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yan K.-H., Yao C.-J., Chang H.-Y., Lai G.-M., Cheng A.-L., Chuang S.-E. The synergistic anticancer effect of troglitazone combined with aspirin causes cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human lung cancer cells. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2010;49(3):235–246. doi: 10.1002/mc.20593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Colotta F., Allavena P., Sica A., Garlanda C., Mantovani A. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(7):1073–1081. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Atsumi T., Singh R., Sabharwal L., et al. Inflammation amplifier, a new paradigm in cancer biology. Cancer Research. 2014;74(1):8–14. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gagliani N., Hu B., Huber S., Elinav E., Flavell R. A. The fire within: microbes inflame tumors. Cell. 2014;157(4):776–783. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Diakos C. I., Charles K. A., McMillan D. C., Clarke S. J. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. The Lancet Oncology. 2014;15(11):e493–e503. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Glass C. K., Saijo K. Nuclear receptor transrepression pathways that regulate inflammation in macrophages and T cells. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2010;10(5):365–376. doi: 10.1038/nri2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Straus D. S., Glass C. K. Anti-inflammatory actions of PPAR ligands: new insights on cellular and molecular mechanisms. Trends in Immunology. 2007;28(12):551–558. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shah Y. M., Morimura K., Gonzalez F. J. Expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in macrophage suppresses experimentally induced colitis. American Journal of Physiology—Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2007;292(2):G657–G666. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00381.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Straus D. S., Pascual G., Li M., et al. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 inhibits multiple steps in the NF-κB signaling pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(9):4844–4849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kapadia R., Yi J.-H., Vemuganti R. Mechanisms of anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective actions of PPAR-gamma agonists. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2008;13(5):1813–1826. doi: 10.2741/2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sharma A. M., Staels B. Review: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and adipose tissue—understanding obesity-related changes in regulation of lipid and glucose metabolism. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2007;92(2):386–395. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Pascual G., Fong A. L., Ogawa S., et al. A SUMOylation-dependent pathway mediates transrepression of inflammatory response genes by PPAR-γ . Nature. 2005;437(7059):759–763. doi: 10.1038/nature03988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lefebvre A. M., Chen I., Desreumaux P., et al. Activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ promotes the development of colon tumors in C57BL/6J-APCMin/+ mice. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(9):1053–1057. doi: 10.1038/2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Pino M. V., Kelley M. F., Jayyosi Z. Promotion of colon tumors in C57BL/6J-APC(min)/+ mice by thiazolidinedione PPARγ agonists and a structurally unrelated PPARγ agonist. Toxicologic Pathology. 2004;32(1):58–63. doi: 10.1080/01926230490261320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Saez E., Tontonoz P., Nelson M. C., et al. Activators of the nuclear receptor PPARγ enhance colon polyp formation. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(9):1058–1061. doi: 10.1038/2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Yang K., Fan K.-H., Lamprecht S. A., et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonist troglitazone induces colon tumors in normal C57BL/6J mice and enhances colonic carcinogenesis in Apc1638 N/+ Mlh1+/- double mutant mice. International Journal of Cancer. 2005;116(4):495–499. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Bagi Z., Koller A., Kaley G. PPARγ activation, by reducing oxidative stress, increases NO bioavailability in coronary arterioles of mice with Type 2 diabetes. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2004;286(2):H742–H748. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00718.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Inoue I., Goto S.-I., Matsunaga T., et al. The ligands/activators for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) and PPARγ increase Cu2+,Zn2+-superoxide dismutase and decrease p22phox message expressions in primary endothelial cells. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 2001;50(1):3–11. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.19415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tinahones F. J., Murri-Pierri M., Garrido-Sánchez L., et al. Oxidative stress in severely obese persons is greater in those with insulin resistance. Obesity. 2009;17(2):240–246. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Olusi S. O. Obesity is an independent risk factor for plasma lipid peroxidation and depletion of erythrocyte cytoprotectic enzymes in humans. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2002;26(9):1159–1164. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Giacco F., Brownlee M. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circulation Research. 2010;107(9):1058–1070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Baynes J. W. Role of oxidative stress in development of complications in diabetes. Diabetes. 1991;40(4):405–412. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Olefsky J. M., Glass C. K. Macrophages, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Annual Review of Physiology. 2010;72(1):219–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Moore K. J., Fitzgerald M. L., Freeman M. W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in macrophage biology: friend or foe? Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2001;12(5):519–527. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Macias-Gonzalez M., Cardona F., Queipo-Ortuño M., Bernal R., Martin M., Tinahones F. J. PPARγ mRNA expression is reduced in peripheral blood mononuclear cells after fat overload in patients with metabolic syndrome. Journal of Nutrition. 2008;138(5):903–907. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.5.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Bilban M., Haslinger P., Prast J., et al. Identification of novel trophoblast invasion-related genes: heme oxygenase-1 controls motility via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ . Endocrinology. 2009;150(2):1000–1013. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Burton J. D., Castillo M. E., Goldenberg D. M., Blumenthal R. D. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ antagonists exhibit potent antiproliferative effects versus many hematopoietic and epithelial cancer cell lines. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2007;18(5):525–534. doi: 10.1097/cad.0b013e3280200414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Schaefer K. L., Wada K., Takahashi H., et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ inhibition prevents adhesion to the extracellular matrix and induces anoikis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Research. 2005;65(6):2251–2259. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Lea M. A., Sura M., Desbordes C. Inhibition of cell proliferation by potential peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma agonists and antagonists. Anticancer Research. 2004;24(5A):2765–2771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Nonn L., Peng L., Feldman D., Peehl D. M. Inhibition of p38 by vitamin D reduces interleukin-6 production in normal prostate cells via mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 5: implications for prostate cancer prevention by vitamin D. Cancer Research. 2006;66(8):4516–4524. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-05-3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Bao B.-Y., Yao J., Lee Y.-F. 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 suppresses interleukin-8-mediated prostate cancer cell angiogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(9):1883–1893. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Moreno J., Krishnan A. V., Swami S., Nonn L., Peehl D. M., Feldman D. Regulation of prostaglandin metabolism by calcitriol attenuates growth stimulation in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2005;65(17):7917–7925. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Wagner N., Wagner K.-D., Schley G., Badiali L., Theres H., Scholz H. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced apoptosis of retinoblastoma cells is associated with reciprocal changes of Bcl-2 and bax. Experimental Eye Research. 2003;77(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4835(03)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kizildag S., Ates H., Kizildag S. Treatment of K562 cells with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces distinct alterations in the expression of apoptosis-related genes BCL2, BAX, BCLXL, and p21. Annals of Hematology. 2010;89(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00277-009-0766-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Peterlik M., Grant W. B., Cross H. S. Calcium, vitamin D and cancer. Anticancer Research. 2009;29(9):3687–3698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Weitsman G. E., Koren R., Zuck E., Rotem C., Liberman U. A., Ravid A. Vitamin D sensitizes breast cancer cells to the action of H2O2: mitochondria as a convergence point in the death pathway. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2005;39(2):266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Ravid A., Koren R. Vitamin D Analogs in Cancer Prevention and Therapy. Vol. 164. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2003. The role of reactive oxygen species in the anticancer activity of vitamin D; pp. 357–367. (Recent Results in Cancer Research). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.De Haes P., Garmyn M., Degreef H., Vantieghem K., Bouillon R., Segaert S. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits ultraviolet B-induced apoptosis, Jun kinase activation, and interleukin-6 production in primary human keratinocytes. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2003;89(4):663–673. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Riachy R., Vandewalle B., Moerman E., et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 protects human pancreatic islets against cytokine-induced apoptosis via down-regulation of the Fas receptor. Apoptosis. 2006;11(2):151–159. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-3558-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Flores O., Wang Z., Knudsen K. E., Burnstein K. L. Nuclear targeting of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 reveals essential roles of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 localization and cyclin E in vitamin D-mediated growth inhibition. Endocrinology. 2010;151(3):896–908. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Jensen S. S., Madsen M. W., Lukas J., Binderup L., Bartek J. Inhibitory effects of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on the G1–S phase-controlling machinery. Molecular Endocrinology. 2001;15(8):1370–1380. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.8.0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Hager G., Kornfehl J., Knerer B., Weigel G., Formanek M. Molecular analysis of p21 promoter activity isolated from squamous carcinoma cell lines of the head and neck under the influence of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 and its analogs. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 2004;124(1):90–96. doi: 10.1080/00016480310015353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Hershberger P. A., Modzelewski R. A., Shurin Z. R., Rueger R. M., Trump D. L., Johnson C. S. 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol (1,25-D3) inhibits the growth of squamous cell carcinoma and down-modulates p21(Waf1/Cip1) in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Research. 1999;59(11):2644–2649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Colston K., Colston M. J., Feldman D. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and malignant melanoma: the presence of receptors and inhibition of cell growth in culture. Endocrinology. 1981;108(3):1083–1086. doi: 10.1210/endo-108-3-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Boyle B. J., Zhao X.-Y., Cohen P., Feldman D. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 mediates 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 growth inhibition in the LNCaP prostate cancer cell line through p21/WAF1. The Journal of Urology. 2001;165(4):1319–1324. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)69892-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Welsh J. Cellular and molecular effects of vitamin D on carcinogenesis. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2012;523(1):107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Rohan J. N. P., Weigel N. L. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 reduces c-Myc expression, inhibiting proliferation and causing G1 accumulation in C4-2 prostate cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2009;150(5):2046–2054. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Wang X., Pesakhov S., Weng A., et al. ERK 5/MAPK pathway has a major role in 1α,25-(OH)2 vitamin D3-induced terminal differentiation of myeloid leukemia cells. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2014;144:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Pendás-Franco N., González-Sancho J. M., Suárez Y., et al. Vitamin D regulates the phenotype of human breast cancer cells. Differentiation. 2007;75(3):193–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Gocek E., Studzinski G. P. Vitamin D and differentiation in cancer. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 2009;46(4):190–209. doi: 10.1080/10408360902982128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Liu M., Lee M.-H., Cohen M., Bommakanti M., Freedman L. P. Transcriptional activation of the Cdk inhibitor p21 by vitamin D3 leads to the induced differentiation of the myelomonocytic cell line U937. Genes & Development. 1996;10(2):142–153. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Pereira F., Larriba M. J., Muñoz A. Vitamin D and colon cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2012;19(3):R51–R71. doi: 10.1530/erc-11-0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]