Abstract

Background

A systematic review was conducted to identify and characterize self-reported sexual function (SF) measures administered to women with a history of cancer.

Methods

Using 2009 PRISMA guidelines, we searched electronic bibliographic databases for quantitative studies published January 2008–September 2014 that used a self-reported measure of SF, or a quality of life (QOL) measure that contained at least one item pertaining to SF.

Results

Of 1,487 articles initially identified, 171 were retained. The studies originated in 36 different countries with 23% from U.S.-based authors. Most studies focused on women treated for breast, gynecologic, or colorectal cancer. About 70% of the articles examined SF as the primary focus; the remaining examined QOL, menopausal symptoms, or compared treatment modalities. We identified 37 measures that assessed at least one domain of SF, eight of which were dedicated SF measures developed with cancer patients. Almost one-third of the studies used EORTC QLQ modules to assess SF, and another third used the Female Sexual Function Inventory. There were few commonalities among studies, though nearly all demonstrated worse SF after cancer treatment or compared to healthy controls.

Conclusions

QOL measures are better suited to screening while dedicated SF questionnaires provide data for more in depth assessment. This systematic review will assist oncology clinicians and researchers in their selection of measures of SF and encourage integration of this quality of life domain in patient care.

Keywords: Sexual Function, Females, Cancer, Quality of Life, Psychosocial

Introduction

Patient-reported sexual function is an essential component of comprehensive care for women with cancer. Although routine assessment of sexual health is still uncommon in oncology settings, measures of sexual function have been used to document compromised sexual function among women with cancer for more than 60 years. Kahanpӓӓ and Gylling (1951) pioneered this work by administering a self-reported questionnaire about sexual activity to women treated for cervical cancer. A decade later, Waxenberg and his colleagues (1960) documented sexual dysfunction following hormonal ablation surgery among breast cancer patients. Similar studies of women with other types of cancer later emerged, including Hodgkin’s disease (Chapman, Sutcliffe, & Malpas, 1979) and colorectal cancer (Deixonne, Baumel, & Domergue, 1982). A limitation of these early studies was the absence of standardized self-reported measures of sexual function. Measures which are ‘standardized’ are ones that, when published, provide data regarding reliability and validity, and information on samples with which the measure was validated, and, perhaps, normative data from reference groups. Standardization is important for making comparisons of individuals (or the same individuals across time, for example) with differing sociodemographic characteristics or disease or treatment histories. Standardization also helps measure the magnitude of expected versus observed sexual functioning. Clinically, using any sexual functioning measure may help patients and/or providers initiate questions about sexual function and improve their communication about sexual functioning (Carter, Stabile, Gunn, & Sonoda, 2013; Dizon, Suzin, & McIlvenna, 2014). Elsewhere, with men treated for prostate cancer, help seeking behaviors for sexual dysfunction appears to be directly related to cancer stage and severity of dysfunction (Schover, Fouladi, Warneke, et al., 2004). Hence, using a standardized measure to monitor sexual function with the same individual at various times in the course of treatment may detect and address difficulties prior to severe dysfunction. Where interventions are implemented, standardized measures are necessary to establish efficacy and to provide a systematic evaluation of short and long-term outcomes. Further, data from standardized measures can be aggregated and compared with normative standards, and thus provide an empirical basis for the selection of interventions and, in turn, formulation of practice guidelines.

The first validated self-reported measure of sexual function, the Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory (DSFI), appeared in 1979 (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1979). Among female oncology patients, subscales of the DSFI subscales were initially used in a study of women with early stage cervical or endometrial cancers (Andersen, Lachenbruch, Anderson, & deProsse, 1986). At least one study of breast cancer patients used the 254-item DSFI in its entirety (Wolberg, Tanner, Romsaas, Trump, & Malec, 1987). The response burden associated with the DSFI led to the creation the Sexual Function After Treatment for Gynecologic Illness Scale, developed for women undergoing radiation therapy for gynecologic and breast cancers (Bransfield, Horiot, & Nabid, 1984). Other measures developed specifically with oncology populations and used with female cancer patients followed, including the Lasry Sexual Functioning Scale for Breast Cancer Patients (Lasry, et al., 1987), the Wilmoth Sexual Behaviors Questionnaire – Female (Wilmoth & Tingle, 2001), the Sexual Function-Vaginal Changes Questionnaire (SVQ; Jensen, Klee, Thranov, & Groenvold, 2004), the Sexual Adjustment and Body Image Scale Dalton, et al., 2009), and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System® Sexual Function and Satisfaction (PROMIS SexFS; Flynn, et al., 2013).

Additional measures of female sexual function, not specific to sexual response and outcomes following cancer, have been used in oncology settings, such as the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women (Taylor, Rosen, & Leiblum, 1994), Sexual Dimensions Instrument for Hispanic Women (Adams, DeJesus, Trujillo, & Cole, 1997), the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI; Rosen, et al., 2000), the Sexual Function Questionnaire (SFQ; Quirk, et al., 2002), and the Sexual Interest and Desire Inventory-Female (Clayton, et al., 2006). Moreover, several self-reported measures designed to assess both male and female sexual function have been administered to women with a cancer history such as the Watts Sexual Function Questionnaire (Watts, 2982), the Golombok Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction (Rust & Golombok, 1986), and the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (McGahuey, et al., 2000).

A number of reviews have discussed sexual function measures used in general populations (Arrington, Cofrancesco, & Wu, 2004, Corona, Jannini, & Maggi, 2006; Lorenz, Stephenson, & Meston, 2011; Rosen, 2002) or used with cancer patients (Althof & Parish, 2013; DeSimone, et al., 2014). One review identified 30 self-reported measures of sexual function used in quantitative studies in women with breast cancer (Bartula & Sherman, 2013), while another identified eight measures used in women with cervical cancer (Ye, Yang, Cao, Lang, & Shen, 2014). The large number of sexual function measures suggests interest in this quality of life domain, but also creates a quandary in the selection of measures appropriate for oncology settings. The goal of this systematic review is to assist oncology clinicians and researchers make more informed choices in selecting self-reported sexual function measures for clinical use. Specifically, we (a) identify studies that administered self-reported standardized measures of sexual function to women with a history of cancer, (b) describe the measures with respect to the purpose, sexual function domains assessed, number of items, psychometric properties and frequency of use, (c) characterize the samples studied, and (d) summarize some of the sexual function outcomes.

Methods

Study setting and design

In March 2013, a writing group from the Scientific Network on Female Sexual Health and Cancer was formed to review measures of sexual function used in studies of female oncology patients. The 2009 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were adopted for the review (PRISMA, n.d.)

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria for studies were as follows: (1) published in a peer-reviewed journal; (2) sample of adult women diagnosed with cancer; (3) use of a self-reported measure of sexual function, satisfaction, distress, body image, or a quality of life measure with sexual function items that had (4) evidence for validity, including psychometric evaluation. The following categories or content were excluded: scholarly review and measure-development-only articles; studies employing qualitative methods only; studies focused solely on sexual information provision, sexual orientation, attitudes, or functioning of sexual partners; and studies focused on non-malignant conditions, non-invasive cancer (i.e., dysplasia, ductal cancer in situ), or prophylactic breast or gynecologic surgery. Also excluded were duplicate publications (e.g., same studies published in different languages or different journals), or ones in Romanian or Japanese as translation was unavailable.

Search strategy

Literature searches were conducted between June 2013 and September 2014 using PubMed and Scopus electronic bibliographic databases. Dates of publication were restricted from January 2008 to September 2014. The year 2008 was used as the starting date because a similar review focused on studies published from 1991 to 2007 (Jeffery, et al., 2009). The initial bibliographic search terms were “neoplasms OR cancer AND sexual function NOT HPV NOT HIV.” Search terms were then expanded to include the names of sexual function or quality of life scales, types of sexual dysfunction (e.g., dyspareunia), specific cancer sites by “quality of life” and “psychosocial,” and terms “sexual satisfaction.”

Study selection

The preliminary screener for article inclusion was the published abstract. Where possible, the full text article was obtained if the abstract described a quantitative study of sexuality or sexual function and mentioned a cancer site applicable to women. The full text article was then scanned by one team member to ascertain if inclusion criteria appeared to be met.

Data Abstraction

Through consensus, we identified required data elements needed in an abstraction coding sheet, including patient characteristics, type of cancer, cancer treatment modality, research design, whether sexual function was a primary study outcome, timing of administration of the sexual function measure relative to time of diagnosis and treatment, sexual function measure(s) and domains assessed, results of the sexual function measures by primary domains, geographic location of the study, study funders, general comments, and recommendation to retain or exclude the study in the final data. We also included coded elements for body image measures and intimate partner issues though we did not directly search the literature for these constructs. Each writing group member was assigned two articles to test the coding sheet. With minor revisions, the coding sheet was finalized in February 2014.

English-language pre-screened articles were then randomly assigned to two team members for abstraction and their decision to retain or reject the article; a third reviewer reconciled differences. Non-English-language articles were abstracted once. Each writing group member abstracted 48 – 60 articles.

Results

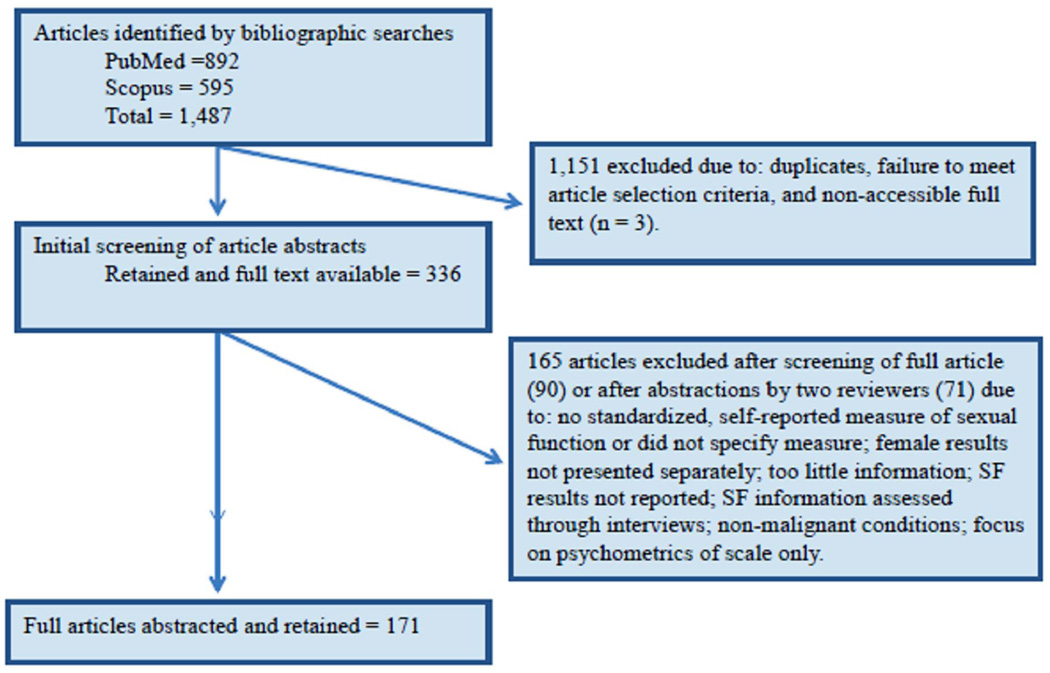

A total of 1,487 articles were identified in the search; 1,151 were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria or were duplicate publications. An additional 165 were excluded after abstraction; the primary reasons were that a standardized measure was not administered, or female sexual function results were not distinguished from male/female samples or were not reported. This process left 171 articles. Details of study inclusion/exclusion are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Article selection

Geographic Location of Selected Studies

Of the retained publications, the articles originated from the United States (22.6%), The Netherlands (8.3%), Italy (7.1%), Germany (7.1%), Australia (6.0%), Canada (6.0%), South Korea (5.4%), Brazil (4.8%), France (3.6%), United Kingdom (3.6%), China (2.4%), Iran (2.4%), and Sweden (2.4%); 2% or less originated from Austria, Bahrain, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Columbia, Denmark, Egypt, Greece, India, Japan, Mexico, Morocco, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sudan, Switzerland, Taiwan, Tunisia, and Turkey.

Research Design

The majority of the selected studies (77%) used a cross-sectional assessment of sexual function. About 18% of the studies administered self-report measures before or during active treatment; the majority of studies assessed sexual function after active treatment. Of the studies (n = 140) that provided information about the time interval between diagnosis or treatment and assessment, nearly 30% included women who were less than 4 years post-diagnosis or treatment. The remaining studies had a broad time interval that extended up to 44 years post diagnosis or treatment. Almost 9% of the studies used two or more non-randomly selected groups to compare those with cancer to those with non-cancer conditions. Another 11% compared two or more non-randomly selected groups in research designs involving repeated measures. Only 7% (n = 12) of the studies used randomly selected groups, either in pretest/posttest repeated-measures designs, or in experimental designs with assignment to treatment conditions.

Cancer Site and Treatment

The cancer site most represented was breast followed by cervix and other gynecologic sites (Table 3). Only two studies focused on survivors of childhood cancer. All but six studies provided some information on cancer treatment including hormonal treatment.

Table 3.

Cancer Sites Represented in the 171 Retained Studies

| Cancer Site | Number of studies (%) |

|---|---|

| Breast | 51 (29.8) |

| Breast and gynecologic | 4 (2.3) |

| Two or more gynecologic sites | 23 (13.5) |

| Ovarian | 5 (2.9) |

| Endometrial | 9 (5.3) |

| Vaginal | 1 (0.6) |

| Vulvar | 5 (2.9) |

| Cervical | 22 (12.9) |

| Colorectal | 14 (8.2) |

| Colon | 1 (0.6) |

| Rectal | 14 (8.2) |

| Anal | 3 (1.8) |

| Rectal and anal | 1(0.6) |

| Bladder | 2 (1.2) |

| Hodgkin’s Disease | 1(0.6) |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1(0.6) |

| Bone | 1(0.6) |

| Head and neck | 2 (1.2) |

| Melanoma | 1(0.6) |

| Multiple adult sites | 8 (4.7) |

| Childhood cancer sites | 2 (1.2) |

Sample Size and Characteristics

Sample sizes ranged from 7 women who underwent neovaginal reconstruction to a series of 1,788 women with a history of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. More than half of studies sampled women with an average or median age between 48 and 60. Some studies focused specifically on women less than age 50, while other studies had a wide age range that extended to women age 90 or older. About 22% of the articles did not provide information on age range, though most provided average or median age. Racial/ethnic characteristics of the female samples were not reported except for 34 studies conducted in the U.S., Canada, or Australia, and one study conducted in Brazil. About 55% of the studies collected some information on the educational level of the female sample.

Almost half of the articles had no information on how many women were sexually active. Some reports provided the percentage of women who were married or who had a partner; three studies recruited or reported on married women only. Only one study specifically focused on women in same-sex relationships; no other studies mentioned sexual orientation. One study included women only if they had been sexually active for 3 years prior to the cancer diagnosis. Several studies had low subject response to the sexual function items without characterizing non-responders; that is, we could not determine if non-response was due to sexual inactivity or another reason. Almost 30% of the selected studies did not have sexual function as a primary focus; most of these studies examined quality of life, menopausal symptoms, or compared treatment modalities.

Sexual Function Measures

Table 1 lists the measures used to assess sexual function in the selected studies, whether the measure was developed with a cancer population, and the type of measure (dedicated measure of sexual function versus quality of life or measure of physical and mental health symptoms). If the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ) modules were considered as one measurement, and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measures were considered as one measure, then a total of 37 unique measures were identified in the studies. The 10 EORTC QLQ modules used in the studies had some overlap of sexual function items. For example, the cervical, breast, ovarian and endometrial modules used the same item for assessment of sexual enjoyment; the breast, colorectal, endometrial, and ovarian cancer modules used the same item to assess sexual interest; and the ovarian, endometrial, and breast modules used the same item to assess sexual activity. A few EORTC QLQ modules contained items not found in other modules, or items with slight differences in wording. Where reported, the number of sexual function items in the EORTC QLQ modules ranged from two (e.g., colorectal and head & neck modules) to seven (cervical module). Three of the four FACIT measures (general spiritual well-being, and endocrine symptoms) used the same sexual function item; the cervix measure used 5 different sexual function items. Eight measures were dedicated measures of sexual function developed with cancer populations. Of these, only the SAQ and SVQ were used in more than two retained studies. We were able to locate extensive documentation on the development and psychometric properties of the SAQ (or FSAQ), SVQ, and PROMIS SexFS; limited or no information was found for the remaining five measures.

Table 1.

Measures of Sexual Function or Quality of Life by Population Used in Development and by Primary Purpose

| .Dedicated Measures of Sexual Function | |

|---|---|

| Developed with Cancer Populations | Developed with Non-Cancer Populations |

| Cancer and Leukemia Group B Sexual Functioning Scale |

Arizona Sexual Experience Scale |

| Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women | |

| Gynaecologic Leiden Questionnaire (GLQ) | |

| Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory (DSFI) | |

| Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Sexual Function and Satisfaction Measures (PROMIS SexFS) |

Female Sexual Distress Scale |

| Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) | |

| Relationship and Sexuality | |

| Golombok Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction | |

| Sexual Activity Questionnaire (SAQ) or Fallowfield’s Sexual Activity Questionnaire (FSAQ) |

Green Climacteric Scale |

| Sexual Adjustment Questionnaire | McCoy Female Sexuality Questionnaire / Personal Experiences Questionnaire - Short Form (SPEQ) |

| Short Sexual Function Scale/Specific Sexual Problems Questionnaire |

Menopausal Sexual Interest Questionnaire |

| Sexual Function-Vaginal Changes Questionnaire (SVQ) |

Menopause-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| Pelvic Organ Prolapse/ Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire |

|

| Profile of Female Sexual Function | |

| Questionnaire for Screening Sexual Dysfunctions | |

| Questionnaire of Marital Sexual Problems | |

| Sexual Function Questionnaire (SFQ) | |

| Sexual Quality of Life-Female (SQOL-F) | |

| Sexual Satisfaction Measurement Tool (in Korean) |

|

| Swedish Sex Survey (SSS) | |

| Watts Sexual Functioning Scale (WSFS) | |

| Measures of Quality of Life and/or Symptom Assessment | |

| Developed with Cancer Populations | Developed with Non-Cancer Populations |

| BREAST –Q Reconstruction Module | Medical Outcomes Study Sexual Functioning Scale (MOS-SF) |

| Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES) |

World Health Organization - Quality of Life −100 |

| Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Event Scale |

Women’s Health Questionnaire |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer -Quality of Life Questionnaire modules and German Testicular Cancer Trial group SX (based on EORTC QLQ Cancer30 and additional items) |

|

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT-G) and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-- Measurement System scales (FACIT) |

|

| Menopausal Symptom Scale | |

| Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors | |

Table 2 presents the identified measures, their sexual function domains, reliability and validity (where available), and authors and year of studies organized by cancer site. The most common domains were sexual desire or interest, frequency of sexual activity, sexual satisfaction, sexual enjoyment, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and dyspareunia. Fourteen measures included at least one domain (or item) related to the sexual relationship or the partner’s sexual function. About half of the measures have reported construct validity or its subtypes discriminant and convergent validity. We were able to find reported levels of reliability or validity for all but eight measures, three of which contained only 1 item on sexual function. As shown, ten EORTC QLQ modules were used in 55 studies in addition to one study that used 5 sexual function items from the EORTC QLQ item bank. Three FACT measures (general scale, cervical cancer scale, and endocrine symptom scale) were used in eight studies. Both the EORTC QLQ and the FACT were developed to assess quality of life following cancer treatment. Among the dedicated measures of sexual function developed with non-cancer populations, the one most commonly used was the Female Sexual Function Inventory (FSFI). A total of 56 studies used the FSFI.

Table 2.

Sexual Function Measures Used in Selected Studies of Women Diagnosed and Treated for Cancer

| Measure Name Scale citation |

Number of Items Related to Sexual Function, Sexual Function-Related Domains, Reliability, Validity |

Cancer Site and References |

|---|---|---|

| Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX) McGahuey CA, Gelenberg AJ, Laukes CA, et al. The Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX): reliability and validity. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(1):25–40. |

5 items Drive, arousal, vaginal lubrication, ability to reach orgasm, satisfaction from orgasm Internal consistency, total scale α = 0.91; test-retest reliability Discriminant validity |

Gynecologic: Cleary, et al., 2011 |

| Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women (BISF – W) Taylor JF, Rosen RC, Leiblum SR. Self-report assessment of female sexual function: Psychometric evaluation of the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women. Arch Sex Behav. 1994;23(6):627–643. |

22 items Desire/sexual Interest, sexual activity, sexual satisfaction Internal consistency α =0.39 – 0.83; test-retest reliability Pearson r = 0.68 – 0.78 Concurrent validity |

Bone: Barrera, et al., 2010 Cervical: Grange, et al., 2013 |

| BREAST –Q Reconstruction Module (BREASTQ) Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Klok JA, Cordeiro PG, Cano SJ. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):345–353. |

16 sexual function items, 226 items total Sexual well-being Person separation index = 0.76 – 0.95; internal consistency α = 0.81 – 0.96; test-retest reliability 0.73 – 0.96 Discriminant validity |

Breast: Zhong, et al., 2012 |

| Cancer and Leukemia Group B Sexual Functioning Scale (CALGB SF) / Sexual Function Related to Cancer Index Kornblith AB, Anderson J, Cella DF, et al. Comparison of psychosocial adaptation and sexual function of survivors of advanced Hodgkin disease treated by MOPP, ABVD, or MOPP alternating with ABVD. Cancer. 1992;70(10):2508–2516. htt;://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_40 |

8 items Sexual interest, activity, sexual attractiveness, acceptance by one’s partner Face validity |

Ovarian: Matulonis, et al., 2008; Mirabeau-Beale, et al., 2009 |

| Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES) Schag CA, Heinrich RL. Development of a comprehensive quality of life measurement tool: CARES. Oncology (Williston Park). 1990;4(5):135–138. |

2 sexual function items: Sexual interest, and sexual dysfunction Internal consistency of SF subscale α = 0.82 – 0.88; test- retest reliability Content validity; construct validity based on factor analysis |

Breast: Rowland, et al., 2009; Webber, et al., 2011; Imayama et al., 2013; Jun, et al., 2011; Rosenberg, et al., 2014; Colorectal: Kasparek, et al., 2012 |

| Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Event Scale http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm Accessed Sept 18, 2014 |

5 sexual function items - females For females, 5 subscales, 1 of which is Vagina and Sexual Function Pain from vagina, vaginal dryness, pain with intercourse, ability to have sexual relationship affected Reliability – not reported Validity – not reported |

Multiple sites: Adams, et al., 2014 Gynecologic: Vaz, et al., 2011 |

| Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory (DSFI) Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The DSFI: a multidimensional measure of sexual functioning. J Sex Marital Ther. 1979;5(3):244–281. |

254 items Information, experience, drive, attitudes, psychological distress, gender role, fantasy, body image, sexual satisfaction, frequency of sexual activity Internal consistency α = 0.57 – 0.97; test-retest reliability for 8 of the 10 subscales ranged from 0.56 – 0.94. Construct validity |

Colorectal: Yu-Hua, 2013; Gynecologic: Carpenter, et al., 2009 (Sexual Satisfaction subscale); Juraskova, et al., 2013; Levin, et al., 2010 |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Bladder - 24 (EORTC QLQ BL24) http://groups.eortc.be/qol/bladder-cancer-eortc-qlq-bls24-eortcqlq-blm30 |

8 sexual function items Level of lubrication, interest, enjoyment, level of activity, discomfort when thinking about sexual contact, fear of harming partner Reliability/validity – not reported |

Bladder: van der AA, et al., 2009 |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life –Breast Cancer -23 (EORTC QLQ BR23) Sprangers MA, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: first results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(10):2756–2768. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/sites/default/files/img/slider/specimen_br23_english.pdf |

3 sexual function items Domains: Sexual function (interest, activity) and sexual enjoyment Internal consistency for sexual function domain α = 0.88 Construct, cross cultural validity |

Breast: Bilfulco, et al., 2012; Brédart, et al., 2011; Den Oudsten, et al., 2010; Dubashi, et al., 2010; Duijts, et al., 2012; Fallbjörk, et al., 2013; Finck, et al., 2012; Gorisek, et al., 2009; Jassim, et al., 2013; Kim, et al., 2012; Moro-Valdezate, et al., 2013; Munshi, et al., 2010; Poorkiani, et al., 2010; Sharif, et al., 2010; Welzel, et al., 2010; Macadam, et al., 2010; Sat-Munoz, et al., 2011; Schlesinger-Raab, et al., 2010; Sun, et al., 2014; Yang, et al., 2011 |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Cervix 24 (EORTC QLQ CX24) Singer S, Kuhnt S, Momenghalibaf A, et al. Patients' acceptance and psychometric properties of the EORTC QLQ-CX24 after surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116(1):82–87. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/sites/default/files/img/specimen_cx24_english.pdf |

7 sexual function items Worry about sex being painful, sexual activity, lubrication, vaginal discomfort, pain during sexual activity, enjoyment, vaginal/vulvar irritation, vaginal bleeding/discharge Internal consistency of Sexual/Vaginal Functioning subscale α = 0.76 Discriminant validity |

Cervical: Bilfulco, et al., 2012; Froeding, et al., 2013; Greimel, et al., 2009; Korfage, et al., 2009; Krikeli, et al., 2011; Le Borgne, et al., 2013; Ljuca, et al., 2011; Mantegna, et al., 2013; Plotti, et al., 2012; Ferrandina, et al., 2014; Quick, et al., 2012; Endometrial: Becker, et al., 2010 Gynecologic: Yavas, et al., 2012 |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Colorectal-38/29 (EORTC QLQ CR38; EORTC QLQ CR29) Sprangers MA, te Velde A, Aaronson NK. The construction and testing of the EORTC colorectal cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire module (QLQ-CR38). European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Study Group on Quality of Life. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(2):238–247. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/sites/default/files/img/specimen_cr29_english.pdf |

2 sexual function items (female) Interest, pain or discomfort during intercourse |

Anal: Bentzen, et al., 2013 Colorectal: Den Oudsten, et al., 2012; Digennero, et al., 2013; Herman, et al., 2013; Kasparek, et al., 2012; Mahjoubi, et al., 2012; Milbury, et al., 2013; Segalla, et al., 2008; Thong, et al., 2011; Thong, Mols, Lemmens, et al., 2011; Trninic, et al., 2009; Gynecologic: Rezk, et al., 2013 Rectal: How, et al., 2012; Konanz, et al., 2013; Peng, et al., 2011; Tiv et al., 2010 Rectal and Anal: Philip, et al., 2013 |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Endometrium 24 (EORTC QLQ EN24) Greimel E, Nordin A, Lanceley A, et al.. Quality of Life Group. Psychometric validation of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Endometrial Cancer Module (EORTC QLQ- EN24). Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(2):183–190. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/sites/default/files/img/specimen_en24_english.pdf |

6 items Interest, sexual activity, lubrication, vaginal discomfort, pain during sexual activity, enjoyment Internal consistency of Sexual/Vaginal Problems subscale α = 0.86 Convergent, divergent, and discriminant validity |

Endometrial: Bilfulco, et al., 2012; Oldenburg, et al., 2013; |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life –Head & Neck Cancer -35 (EORTC QLQ HN35) Bjordal K, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Tollesson E, et al. Development of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) questionnaire module to be used in quality of life assessments in head and neck cancer patients. EORTC Quality of Life Study Group. Acta Oncol. 1994;33(8):879– 885. |

2 items Sexual interest, sexual enjoyment Internal consistency not reported Content, discriminant validity |

Head & Neck: Psoter, et al., 2012; Low, et al., 2009 |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Item Bank van de Poll-Franse LV, Mols F, Gundy CM, et al. Normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC-sexuality items in the general Dutch population. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:667–675. |

5 sexual function items selected Sexual activity, interest, enjoyment, lubrication, pain during intercourse |

Colorectal: Vissers, et al., 2014 |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life –Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer-30 (EORTC QLQ MBL30) http://groups.eortc.be/qol/modules-development-and-available-use |

Number of sexual function items not yet published |

Gynecologic: Rezk, et al., 2013 |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Ovarian- 28 (EORTC QLQ OV28) Greimel E, Bottomley A, Cull A, et al. An international field study of the reliability and validity of a disease-specific questionnaire module (the QLQ-OV28) in assessing the quality of life of patients with ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(10):1402– 1408. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/sites/default/files/img/ov28_english_specimen.pdf |

4 sexual function items Sexual interest, sexual activity, sexual enjoyment, vaginal lubrication Internal consistency of sexual function domain α = 0.78– 0.90; test-retest reliability interclass correlation = 0.74 Construct validity |

Ovarian: Bilfulco, et al., 2012; Minig, et al., 2012; Nout, et al., 2009 |

| EORTC QLQ supplemental vulva-specific module – http://groups.eortc.be/qol/eortcqol-module-cancer-vulva |

Number of sexual function items not yet reported Sexual activity, sexual problems Validation in progress |

Vulvar: Gunter, et al., 2014 |

| Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS) or FSDS-revised Derogatis LR, Rosen R, Leiblum S, et al. The Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS): initial validation of a standardized scale for assessment of sexually related personal distress in women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(4):317–330. |

Revised: 13 items Sexual dissatisfaction, bother, unhappiness (unidimensional) Construct validity |

Breast: Frechette, et al., 2013; Raggio, et al., 2014; Schover, et al., 2014 Gynecologic: Brotto, Erskine, et al., 2012; Brotto, Heiman, et al., 2008; Brotto, Smith, et al., 2013; Classen, et al., 2013 |

| Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimen- sional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther 2000;26:191–208. http://www.fsfiquestionnaire.com/FSFI%20questionnaire2000.pdf |

19 items Desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, sexual satisfaction, pain Internal consistency α >.90 Construct validity |

Multiple sites: Rodrigues, et al., 2012; Rouanne, et al., 2013; Vomvas, et al., 2012 Anal: Corte, et al., 2011 Bladder: Ali-El-Dein et al., 2013 Breast: Alder, et al., 2008; Boehmer, et al., 2013; Cavalheiro, et al., 2012; Frechette, et al., 2013; Juraskova, et al., 2013; Neto, et al., 2013; Park, et al., 2013; Pumo et al., 2012; Raggio, et al., 2014; Safarinejad, et al., 2012; Sbitti, et al., 2011; Schover, et al., 2012; Schover et al., 2013; Schover, et al., 2014; Vieira, et al., 2013 Colorectal: Bohm, et al., 2008; Liang, et al., 2008; McGlone, et al., 2012; Milbury, et al., 2013; Reese, et al., 2012; Reese, et al., 2014; Traa, et al., 2012 Cervical: Becker, et al., 2010; Carter, et al., 2008; Carter, et al., 2010; Froeding, et al., 2013; Harding, et al., 2014; Song, et al., 2012; Serati, et al., 2009; Tsai, et al., 2011 Gynecologic: Brotto, Erskine, et al., 2012; Brotto, Heiman, et al., 2008; Brotto, Smith, et al., 2012; Carpenter, et al., 2009; Chun, et al., 2008; Chun, et al., 2011; Fotopoulou, et al., 2008; Harter, et al., 2013; Onujiogu, et al., 2011; Pilger, et al., 2012; Breast and gynecologic: Schover, et al., 2013 Endometrial: Damast, et al., 2012; Damast, et al., 2014 Rectal: Stănciulea, et al., 2013; Contin, et al., 2014; Segelman, et al., 2013 Rectal and Anal: Philip, et al., 2013 Vaginal: Yin, et al., 2013 Vulvar: de Melo Ferreira, et al., 2012; Forner, et al., 2013; Hazewinkel, et al., 2012 |

| Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-- Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp) Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, et al. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the Functional Asessment of Chronic Illness Therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(1):49–58. |

1 sexual function item Sexual satisfaction |

All sites: Maruelli, et al., 2014 |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT-G) Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993;11: 570–579. http://www.facit.org/FACITOrg/Questionnaires |

1 sexual function item Sexual satisfaction |

Gynecologic: Levin, et al., 2010 Multiple sites: Maruelli, et al., 2014 |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Cervix (FACT-CX) http://www.facit.org/FACITOrg/Questionnaires |

5 sexual function items Bother by vaginal discharge, bleeding, odor; fear of having sex; feeling of sexual attractiveness; vaginal size; sexual interest Internal consistency and validity not reported for sexual function-related items |

Cervical: Carter, et al., 2008; Ditto, et al., 2009; Fernandes, et al., 2010; Tian et al., 2013 |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Endocrine Symptoms (FACT-ES) Fallowfield LJ, Leaity SK, Howell A, et al. Assessment of quality of life in women undergoing hormonal therapy for breast cancer: Validation of an endocrine symptom subscale for the FACT-B. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;55(2):189–99. |

1 sexual function item Sexual satisfaction |

Multiple sites: Absolom et al., 2008 Breast: Frechette, et al., 2013 |

| German Testicular Cancer Trial group SX (based on EORTC QLQ Cancer30 and additional items) Flechtner H, Rüffer JU, Henry- Amar M, et al. Quality of life assessment in Hodgkin's disease: a new comprehensive approach. First experiences from the EORTC/GELA and GHSG trials. EORTC Lymphoma Cooperative Group. Groupe D'Etude des Lymphomes de L'Adulte and German Hodgkin Study Group. Ann Oncol. 1998;9 Suppl 5:S147–154. |

45 items total; number of sexual function items not provided Sexual interest, sexual activity, and satisfaction Reliability/validity not reported |

Hodgkin’s Disease: Behringer, et al., 2013 |

| Golombok Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction (GRISS) Rust J, Golombok S. The GRISS: a psychometric instrument for the assessment of sexual dysfunction. Arch Sex Behav. 1986;15(2):157–165. |

28 items (male and female) Anorgasmia, vaginismus, noncommunication, frequence of sexual activity, avoidance of sexual activity, sexual dissatisfaction Internal consistency α = 0.72 – 0.90; split-half reliability − 0.94 (females) Discriminant, predictive, and construct validity |

Colorectal: Traa, et al., 2012 |

| Green Climacteric Scale (GCS) Greene JG. Constructing a standard climacteric scale. Maturitas. 1998;29(1):25–31. |

21 items, 1 sexual function item Interest |

All sites: Marino, et al., 2013 Breast: Sayakhot, et al., 2011 |

| Gynaecologic Leiden Questionnaire (GLQ) Pieterse QD, Ter Kuile MM, Maas CP, et al. The Gynaecologic Leiden Questionnaire: psychometric properties of a self-report questionnaire of sexual function and vaginal changes for gynaecological cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2008;17(7):681–689. |

7 sexual function items Sexual complaints, sexual function, orgasm Convergent, divergent, concurrent, and discriminant validities |

Cervical: Pieterse, et al., 2013 |

| Index of Female Satisfaction (IFS) Hudson WW, Harrison DF, Crosscup PC. A short-form scale to measure sexual discord in dyadic relationships. J Sex Res 1981; 7(2):157–174. |

25 items Sexual behaviors, attitudes, affective states associated with sexual relationship of couple Internal consistency α = 0.91 – .93; test-retest reliability = 0.93 |

Breast: Finck, et al., 2012 |

| McCoy Female Sexuality Questionnaire (MSFQ)/ and MSFQ short form, Personal Experiences Questionnaire (SPEQ) McCoy NL, Matyas JR. Oral contraceptives and sexuality in university women. Arch Sex Behav. 1996;25:73–90. Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Dudley E. Short scale to measure female sexuality: adapted from McCoy Female Sexuality Questionnaire. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:339–351. |

MSFQ: 19 items SPEQ: 9 items MSFQ: Sexual satisfaction, sexual thoughts/fantasies, frequency of sexual activity, vaginal lubrication, orgasm, partner’s sexual function SPEQ: Feelings for partners, sexual responsivity, vaginal dryness/dyspareunia, frequency of sexual activity, libido, partner sexual function MSFQ: internal consistency α = 0.74, test-retest reliability = 0.69 – 0.95 SPEQ: α = 0.74 – 0.95 Construct validity |

MSFQ Breast: Biglia, et al., 2010; Davis, et al., 2010 SPEQ Breast: Sayakhot, et al., 2011 |

| Medical Outcomes Study Sexual Functioning Scale (MOS-SF) Sherbourne, CD. Social Functioning: Sexual Problems Measures. In: Stewart, AL.; Ware, JE., Eds. Measuring Functioning and Well-Being. Durham and London: Duke University Press; 1992, pp. 194–204. |

4 items Sexual arousal, sexual interest, unable to relax and enjoy sex, orgasm Internal consistency (females) α = 0.90 |

Childhood: Zebrack, et al., 2010 Anal: Das, et al., 2010 |

| Menopausal Sexual Interest Questionnaire (MSIQ) Rosen RC, Lobo RA, Block BA, et al. Menopausal Sexual Interest Questionnaire (MSIQ): A unidimensional scale for the assessment of sexual interest in postmenopausal women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2004;30(4):235– 250. |

10 items Sexual interest, sexual desire, sexual responsiveness Internal consistency consistency α > 0.86; test-retest reliability Pearson r = 0.52–0.76; construct validity |

Breast and gynecologic: Schover, et al., 2013; Schover, et al., 2014 |

| Menopause-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQOL) Hilditch JR, Lewis J, Peter A, et al. A menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire: Development and psychometric properties. Maturitas. 1996;24(3):161–175. |

3 sexual function items Internal consistency α 0.77; content, discriminant, and construct validity |

Breast: Panjari, et al., 2011; Davis, et al., 2014 |

| Menopausal Symptom Scale (MSS) Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, et al. Managing menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(13):1054–1064. |

3 items, vaginal subscale Vaginal subscale: vaginal dryness, genital itching/ irritation, and pain with intercourse Internal consistency α = 0.73 |

Breast: Morrow, et al., 2014 |

| Pelvic Organ Prolapse/ Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12) Rogers RG, Coates KW, Kammerer-Doak D. et al. A short form of the pelvic organ prolapsed/urinary incontinence sexual questionnaire (PISQ-12). Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2003;14:164–168. |

12 items, 10 items relevant to female sexual function Arousal, satisfaction, pain, incontinence interference with sexual function, vaginal function, emotional reaction to sexual activity, orgasm, partner sexual function Discriminant validity |

Gynecologic: Rutledge, et al., 2010 |

| Profile of Female Sexual Function (PFSF) Derogatis L, Rust J, Golombok S, et al. Validation of the Profile of Female Sexual Function (PFSF) in surgically and naturally menopausal women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2004;30(1):25–36. |

37 items Sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, sexual pleasure, sexual concerns, sexual responsiveness, and sexual self-image Internal consistency α = 0.74 – 0.95; test-retest reliability = 0.58 – 0.91 |

Breast: Biglia et al., 2010 |

| Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Sexual Function and Satisfaction Measures (PROMIS SexFS) Flynn KE, Lin L, Cyranowski JM, et al. Development of the NIH PROMIS ® Sexual Function and Satisfaction measures in patients with cancer. J Sex Med. 2013;10 Suppl 1:43– 52. Weinfurt KP, Lin L, Bruner, DW, et al.. Development and initial validation of the PROMIS Sexual Function and Satisfaction Measures, version 2.0. 2014 In press. |

Version 1.0 – 10 items (females) Version 2.0 – 13 items (females) Interest in sexual activity, lubrication, vaginal discomfort, orgasm, anal discomfort, therapeutic aids, sexual activities, interfering factors, global satisfaction with sex life Item response theory; items calibrated Content, discriminant, convergent validity |

Cervical: Zaid, et al., 2014 [used 9 PROMIS SexSF items] |

| Questionnaire for Screening Sexual Dysfunctions (QSD) Vroege JA (1994) Vragenlijst voor het signaleren van seksuele dysfuncties (VSD). 5de versie. Academisch Ziekenhuis Utrecht, Afdeling Medische seksuologie/Nederlands Instituut voor Sociaal Sexuologisch Onderzoek, Utrecht |

12 items (?) Desire, arousal, orgasm, pain, frequency, distress |

Breast: Kedde, et al., 2013 |

| Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors (QLACS) Avis NE, Smith KW, McGraw S, et al. Assessing quality of life in adult cancer survivors (QLACS). Qual Life Res. 2005;14(4):1007–1023. |

2 sexual function items Dissatisfaction with sex life; bothered by inability to function sexually Internal consistency for sexual problems domain α = 0.72 Criterion validity |

Breast: Morrow, et al., 2014 |

| Questionnaire of Marital Sexual Problems (QMSP) Cibor R. Struktura “ja” a motywy podejmowania leczenia. Katowice: Uniwersytet Śląski; 1994. (as reported by Pietrzyk, 2009) |

14 items Quality of marital sexual relations, desire, orgasm, satisfaction, enjoyment, avoidance of sexual activity, fear of sexual activity, partner sexual behavior Internal consistency α = 0.77 |

Endometrial: Pietrzyk, 2009 |

| Relationship and Sexuality (RSS) Berglund G, Nystedt M, Bolund C, et al.. Effect of endocrine treatment on sexuality in premenopausal breast cancer patients: a prospective randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2788–2796. |

13 sexual function items Function, frequency, fear, emotional closeness/distance, affection, sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, and frequency Internal consistency α = 0.77 – 0.88 |

Breast: Brédart, et al., 2011; Zaied, et al., 2013 |

| Sexual Activity Questionnaire (SAQ) or Fallowfield’s Sexual Activity Questionnaire (FSAQ) Thirlaway K, Fallowfield L, Cuzick J. The Sexual Activity Questionnaire: A measure of women's sexual functioning. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(1):81–90. Atkins L, Fallowfield LJ. Fallowfield's Sexual Activity Questionnaire in women with without and at risk of cancer. Menopause Int. 2007;13(3):103– 109. |

10 items Pleasure, discomfort (lubrication, pain), habit Test-retest reliability, Pearson r = 0.65 – 1.0 Discriminant validity |

All sites: Absolom, et al., 2008; Marino, et al., 2013 Breast: Brédart, et al., 2011; Duijts, et al., 2012; Juraskova, et al., 2013 Cervical: Greimel, et al., 2009 Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: Beckjord, et al., 2011 Ovarian: Campos, et al., 2012; Hopkins, et al., 2014; Liavaag, 2008 Gynecologic : Harter, et al., 2013 |

| Sexual Adjustment Questionnaire –(SAQ-W&M) Waterhouse J, Metcalf MC. Development of the Sexual Adjustment Questionnaire. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1986;13:53– 59. |

110 items Desire, relationship, activity level, arousal, orgasm, techniques, satisfaction. Test-retest reliability 0.67 Construct validity |

Cervical: Greenwald & McCorkle, 2008 (used 6 items from SAQ-W&M)) |

| Sexual Function Questionnaire (SFQ) Quirk FH, Heiman JR, Rosen RC, et al. Development of a sexual function questionnaire for clinical trials of female sexual dysfunction. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11(3):277–289. Quirk F, Haughie S, Symonds T. The use of the Sexual Function Questionnaire as a screening tool for women with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2005;2(4):469–477. |

31 items Desire, physical arousal- sensation, physical arousal- lubrication, enjoyment, orgasm, pain, and partner relationship Internal consistency for domains α = 0.65 – 0.91; test- retest reliability - 0.21 to 0.71 Discriminant validity |

Breast: Herbenick, et al., 2008 Gynecologic: Brotto, Erskine, et al., 2012 Colorectal: Reese, et al., 2014 |

| Sexual Function-Vaginal Changes Questionnaire (SVQ) Jensen PT, Klee MC, Thranov I, et al. Validation of a questionnaire for self-assessment of sexual function and vaginal changes after gynaecological cancer. Psychooncology. 2004; 13:577–592. |

20 items Sexual activity, interest, global sexual satisfaction, body image; sexual function, vaginal changes, intimacy Internal consistency α = 0.76 to 0.83. Content validity |

Cervical: Froeding, et al., 2013 Breast: Stafford, et al., 2011 Colorectal: Bruheim, et al., 2010 Endometrial: Friedman, et al., 2011; Rowlands, et al., 2014 Gynecologic: Stafford, et al, 2011 Quick, et al., 2012; McCallum, et al., 2014 Rectal: Braendengen, et al., 2011; Bregendahl, et al., 2014 |

| Sexual Quality of Life-Female (SQOL-F) Symonds T, Boolell M, Quirk F. Development of a questionnaire on sexual quality of life in women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005 Oct–Dec;31(5):385–97. |

18 items Female sexual dysfunction: Self-esteem, emotional issues, and relationship issues Internal consistency α = 0.95 Convergent, discriminant validity |

Gyn: Golbasi, et al., 2012 |

| Sexual Quociente –Feminino (SQ-Feminino) Abdo CHN. Quociente sexual feminino: Um questionário brasileiro para avaliar a atividade sexual da mulher. Diagn Tratamento 2009;14(2):89–91. [Portugese] http://files.bvs.br/upload/S/1413-9979/2009/v14n2/a0013.pdf |

10 items Sexual fantasies/thoughts, interest, arousal, lubrication, vaginal function, ability to concentrate during sexual intercourse, orgasm, satisfaction Internal consistency tested but not reported Construct validity |

Breast: Manganiello, et al., 2011 |

| Sexual Satisfaction Measurement Tool (in Korean) Kim SN, Chang SB, Kang HS. Development of Sexual Satisfaction Measurement Tool. J Nurs Acad Soc. 1997;27(4):753–764. |

17 items Situational factors, response factors Internal consistency α = 0.91 Content validity |

Breast: Jun, et al., 2011 |

| Short Sexual Function Scale (SSFS) and Specific Sexual Problems Questionnaire (SSPQ) Aerts L, Enzlin P, Verhaeghe J, et al.. Psychologic, relational, and sexual functioning in women after surgical treatment of vulvar malignancy: a prospective controlled study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2014;24:372–380. |

SSFS: 3 items SSPQ: 4 items SSFS: Desire, lubrication, orgasm SSPQ: Dyspareunia, abdominal pain, orgasm SSFS Internal consistency α = 0.89 SSPQ Internal consistency α = 0.93 |

Vulvar: Aerts, et al., 2014 |

| Swedish Sex Survey (SSS) Helmius G. The 1996 Swedish Sex Survey : an introduction and remarks on changes in early sexual experiences. Scand J Sexol. 1998;1:63–70. https://bibliotek.kk.dk/ting/object/870971%3A84726567 |

13 items used Interest, orgasmic dysfunction, lubrication, dyspareunia Reliability/validity not reported |

Breast: Baumgart, et al., 2013 |

| Watts Sexual Functioning Scale (WSFS) Watts RJ. Sexual functioning, health beliefs, and compliance with high blood pressure medications. Nurs Res. 1982;31(5):278–283. Watts Sexual Function Questionnaire (WSFQ) Kristofferzon ML, Johansson I, Brännström M, et al. Evaluation of a Swedish version of the Watts Sexual Function Questionnaire (WSFQ) in persons with heart disease: a pilot study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;9(3):168–174. |

WSFS 15 items Arousal/desire, satisfaction, problems with sexual intercourse, attitudes Internal consistency α = 0.8 (per Decker) |

Breast: Abasher, et al., 2009; Decker et al., 2012 |

| WHOQOL-100 http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/76.pdf |

4 sexual function items Sexual satisfaction: assessment of sex life, fulfillment of sexual needs, satisfaction, bother by problems in sex life Internal consistency α = 0.83, test-retest reliability Discriminant, content validity |

Breast: Den Oudsten, et al., 2010 |

| Women’s Health Questionnaire (WHQ- Sexual Function subscale) Hunter MS. The Women's Health Questionnaire (WHQ): Frequently asked questions (FAQ). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003 10;1:41. |

3 sexual function items (optional) Internal consistency of sexual function items α = 0.59 |

Breast: Sismondi, et al., 2011 Childhood cancer: Ford, et al., 2014 |

The number of sexual function items administered in the selected studies ranged from one item (e.g., FACT-ES) to 254 items (DSFI). Quality of life measures, such as the FACIT measurement system, the MOS Sexual Function Scale, the QLACS, the WHOQOL, and the WHQ typically had fewer items. Most EORTC QLQ cancer site-specific modules had 5 or less sexual function items, fewer items than found in the 10-item SAQ, the 27-item SAQ, the 19-item FSFI, and the 10-item PROMIS SexFS-Female (brief profile, version 2).

Study Results

With few exceptions, the self-reported measures documented a decrease in sexual satisfaction and activity compared to women without cancer or healthy controls, or compared to normative values established on general, non-cancer populations. Using 9 items from the PROMIS SexFS, one study found no difference between the SF scores of women with cervical cancer compared to average scores (t-scores) established with a large cancer population (Zaid, et al., 2014). Another study found no difference in average FSFI scores between women who underwent vulvectomy and iguinofemoral lymphadenectomy for vulvar cancer and healthy women; however, only 6 study participants were sexually active (deMelo Ferreira, et al., 2012).

Sexual function measures were used to evaluate intervention outcomes in 16 studies. For example, the Profile of Female Sexual Function (PFSF) showed that estriol and estradiol vaginal preparations improved sexual function while vaginal moisturizer decreased sexual function among women treated for breast cancer (Biglia, et al., 2010). Using the FSFI, a cognitive behavioral intervention was found to improve sexual function along the domains of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and satisfaction, although no change in pain was observed (Brotto, Erskine, et al., 2008). Similarly, the FSFI was used to document improvements in desire, arousal, orgasm, and satisfaction following a psychoeducational intervention designed to address sexual dysfunction among gynecologic cancer patients (Brotto, Heiman, et al., 2008). The FSFI also showed that peer counseling improved sexual function at 6 months follow up after breast cancer treatment assessment, although, compared to controls, the advantage was lost at 1-year follow up (Schover, et al., 2011).

Several studies examined sexual function over time. The sexual measures used in prospective research designs all had pre-established test-retest reliability. Subscales of the DSFI (Drive, Satisfaction, and Global Sexual Satisfaction Index) were administered three times after surgery for gynecologic cancer, and worse sexual function and quality was found at 12 months compared to baseline and 6-month assessments (Juraskova, et al., 2013). Three administrations of the EORTC QLQ BR23 were administered periodically for one year after breast cancer surgery; sexual function scores decreased somewhat over time (Moro-Valdezate, et al., 2013). Likewise, a three-time assessment of sexual function using the GLQ showed an increase in sexual problems over a 2-year period (Pieterse, et al., 2013). Among those who remained disease-free for 2 years after the diagnosis of cervical cancer, improved sexual function outcomes were found with repeated measures of the EORTC QLQ CX24 (Mantegna, et al., 2013). One study using the EORTC QLQ CR38 documented that sexual function decreased at 3 months following pelvic exenteration but nearly returned to baseline levels after one year (Rezk, et al., 2013). In a cohort of breast cancer patients who were administered the CARES, a measure with 3 sexual function items, some aspects of sexual function was found to improve over the course of the first year posttreatment (Webber, et al., 2011).

The majority of the studies examined sexual function in relation to sociodemographic, tumor stage, physical or mental health, or treatment modalities. For example, sexual activity, as measured by items from the Sexual Adjustment Questionnaire, was positively related to higher income, white race, and earlier stage of cervical cancer (Greenwald & McCorkle, 2008). Better sexual function, as measured by the Chinese version of the FSFI, was predicted by higher education, lower age, lower cancer stage, and having received counseling (Tsai, et al., 2011). Elsewhere, poorer physical health among women with head and neck cancer was positively correlated with sexual problems as evaluated with the EORTC-QLQ–H&N35 (Psoter, Aguilar, Levy, Baek, & Morse, 2012). Similarly, presence of symptoms commonly found after breast cancer treatment were related to poorer sexual outcomes as measured by the Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-BR23 (Yang, Kim, Heo, & Lim, 2011). Worse sexual function, assessed with the French version of the EORTC QLQ-CX24, was found among women treated for cervical cancer with adjuvant radiation therapy compared to those treated with surgery alone (Le Borgne, et al., 2013). As measured with the Italian version of the EORTC QLQ-OV28, sexual outcomes for women with gynecologic cancers did not significantly change one month after laparotomy although other quality of life domains were adversely affected (Minig, et al., 2013). Among breast cancer patients, FSFI scores were negatively related to the number of chemotherapy cycles (Park & Yoon, 2013). Also, based on EORTC QLQ-CR38 scores, women with a history of colorectal cancer treated with adjuvant chemotherapy had similar levels of sexual function as those treated with surgery only (Thong, et al., 2011).

Discussion

Our review of quantitative studies published between 2008 and 2014 found considerable diversity with respect to geographic location, population characteristics, research designs, and selected measures. Representation of studies from 36 countries suggests international interest in this area of research and the importance of including non-English articles in similar reviews. We also found that most of the studies used retrospective, one-time assessment designs. With few exceptions, all studies documented some aspect of compromised sexual function following cancer treatment or compared to healthy controls. Collectively, these findings suggest that all measures were able to detect at least some change in sexual function over time, or were able to discriminate between groups. Most of the measures have documented evidence of internal reliability, and content and construct validity. As of yet, no measures appear to have reported levels of external validation, i.e., comparisons to data derived from clinical findings or patient interviews.

Most of the measures contain domains of desire/interest, and sexual satisfaction or enjoyment. One-third of the measures have domains reflecting the sexual response cycle model (arousal, lubrication, orgasm). A domain or item specific to levels of sexual activity was present in only 13 measures and most of the EORTC QLQ modules (bladder, breast, cervix, endometrium, ovarian, vulvar).. The FSFI, used in one-third of the studies, does not provide direct information about sexual activity unless each item’s response options are analyzed separately from the summed score (Baser, Li, & Carter, 2012). This frequent use of the FSFI may explain why nearly half of the studies had no information on sexual activity.

The evidence for sexual concerns among women with cancer is most informed by two measures: the EORTC QLQ cancer-specific modules and the FSFI. Limitations of the EORTC QLQ modules are that they contain few sexual function items, do not use the same sexual function items across the modules, and do not appear to have published normative values for the sexual function items. Still, these modules, as well as the FACT/FACIT modules, were developed with and for cancer populations, provide screening items that may promote patient-clinician discussion, and permit some comparison of sexual function with other quality of life constructs. The FSFI, originally developed for use in clinical trials of pharmacological treatment for male sexual dysfunction (Goldstein, et al., 2005), permits comparisons through cutoff scores established to distinguish sexual dysfunction in non-cancer populations (Rosen, et al., 2000). Our review also found examples of the FSFI successfully measuring change in sexual function over time (e.g., Carter, Sonoda, Chi, Raviv, & Abu-Rustum, 2008), effectiveness of interventions (e.g., Schover, et al., 2013), and differential impact of cancer treatment approaches (e.g., McGlone, Khan, Flashman, Khan, & Parvaiz, 2012).

A few other measures merit further discussion because of their psychometric robustness, dedicated focus, and their development with and for cancer patients, namely the SAQ, SVQ and the PROMIS SexFS. The SAQ was developed with women enrolled in trials of prophylactic tamoxifen then subsequently tested in populations of women with advanced ovarian cancer or at risk for ovarian cancer (Atkins & Fallowfield, 2007). The 20-item SVQ was developed as a supplement to the EORTC QLQ-C30 (Jensen, et al., 2004). The SVQ went through extensive qualitative and quantitative testing with more than 350 Danish women with gynecologic cancer, as well as input from oncology clinicians. Similar to the iterative process used to develop the SVQ, the PROMIS SexFS was developed with more than 800 U.S. male and female cancer patients during active treatment or follow-up care for multiple cancer sites (Flynn, et al., 2013; Weinfurt, et al., in press). Features that set the PROMIS SexFS apart from the other identified measures include the use of item response theory (IRT) to estimate latent sexual function constructs, to calculate differential item functioning, and to assess measurement invariance for each domain. Qualitative development included special populations such as individuals with low literacy and those who identify as gay, lesbian or bisexual. Brief profile measures of the PROMIS SexFS and supplemental items from item banks are available through the Assessment Center (n.d.). Additionally, PROMIS scores are provided on a common metric (t-scale), and normed to a mixed cancer population and the U.S. general population. The use of common metrics or linked studies that crosswalk scores from one measure to another is one way to address the proliferation of multiple instruments assessing the same domains. Common metrics from PROMIS measures and other patient-reported outcomes are being made available through PROsetta Stone® (n.d.).

Implications for Clinical Practice.

All measures identified in this literature review find that women treated for cancer frequently report symptoms associated with sexual dysfunction such as decreased interest in sexual activity, difficulties with lubrication, and vaginal pain. Unequivocally, these findings support the integration of sexual function assessment into the care of women undergoing cancer treatment or those with a history of cancer. While the large number of identified instruments complicates the choice of measures, clinicians may narrow their options by dichotomizing the measures into screeners, or those with less than three items, versus more comprehensive assessments. Measures such as the FACT or FACIT modules, CARES, and some modules of the EORTC QLQ may serve as useful screeners of sexual concerns but are unlikely to yield information sufficient to identify sexual dysfunction. Measures with multiple sexual function domains, including sexual activity, intimacy, partner function, and body image, would be useful for evaluating treatment side-effects or the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions. Where a more complete assessment of treatment side effects is needed, clinicians are advised to use a dedicated measure of sexual function, preferably one developed with cancer patients (e.g., Sexual Activity Questionnaire or Fallowfield’s Sexual Activity Questionnaire, Sexual Function-Vaginal Changes Questionnaire, and PROMIS SexFS). Other considerations in measure selection are the use of calibrated items and normative values in order to facilitate comparisons with other groups or populations. Consistent application of high quality, sexual function measures will facilitate patient-provider communication about sexual function, and eventually lead to improved outcomes for this dimension of quality of life too often overlooked in oncology care.

Contributor Information

Diana D. Jeffery, Health Psychologist Washington, D. C. diana.d.jeffery.civ@mail.mil

Lisa Barbera, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Odette Cancer Research Program, 2075 Bayview Avenue, Toronto, ON M4N 3M5 Canada Lisa.Barbera@sunnybrook.ca.

Barbara L. Andersen, Ohio State University, College of Arts & Sciences, 1835 Neil Avenue Columbus, OH 43210 U.S.A. andersen.1@osu.edu

Amy K. Siston, University of Chicago, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral, Psycho-Oncology Service, A27 South Maryland Avenue Chicago, IL 60637 U.S.A. asiston@yoda.bsd.uchicago.edu

Anuja Jhingran, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Department of Radiation Oncology, 1515 Holcombe Boulevard, Houston, TX 77030 ajhingra@mdanderson.org.

Shirley R. Baron, Northwestern University, Department of Clinical Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Chicago, IL U.S.A. shirleybaron@gmail.com

Jennifer Barsky Reese, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Cancer Prevention and Control Program, 333 Cottman Avenue Philadelphia, PA 19111 U.S.A. jennifer.reese@fccc.edu

Deborah J. Coady, New York University Langone Medical Center, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 85-15 67th Road New York, New York 11374 U.S.A. debbidoc@aol.com.

Jeanne Carter, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Departments of Surgery and Psychiatry, 1275 York Avenue New York, New York 10065 U.S.A. carterj@mskcc.org

Kathryn E. Flynn, Medical College of Wisconsin, Department of Medicine, Center for Patient Care & Outcomes Research, 8701 Watertown Plank Rd Milwaukee, WI 53226 U.S.A. kflynn@mcw.edu

References

- Adams J, DeJesus Y, Trujillo M, Cole F. Assessing sexual dimensions in Hispanic women. Development of an instrument. Cancer Nursing. 1997;20(4):251–259. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199708000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althof SE, Parish SJ. Clinical interviewing techniques and sexuality questionnaires for male and female cancer patients. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2013;10(Suppl 1):35–42. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen BL, Lachenbruch PA, Anderson B, deProsse C. Sexual dysfunction and signs of gynecologic cancer. Cancer. 1986;57(9):1880–1886. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860501)57:9<1880::aid-cncr2820570930>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrington R, Cofrancesco J, Wu AW. Questionnaires to measure sexual quality of life. Quality of Life Research. 2004;13:1643–1658. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-7625-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment CenterSM. [Accessed February 12, 2015]; (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.assessmentcenter.net. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins L, Fallowfield LJ. Fallowfield's Sexual Activity Questionnaire in women with without and at risk of cancer. Menopause International. 2007;13(3):103–109. doi: 10.1258/175404507781605578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartula I, Sherman KA. Screening for sexual dysfunction in women diagnosed with breast cancer: systematic review and recommendations. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2013;141(2):173–185. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2685-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baser RE, Li Y, Carter J. Psychometric validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118(18):4606–4618. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglia N, Peano E, Sgandurra P, Moggio G, Panuccio E, Migliardi M, et al. Low dose vaginal estrogens or vaginal mositurizer in breast cancer survivors with urogenital atrophy: A preliminary study. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2010;26(6):404–412. doi: 10.3109/09513591003632258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bransfield DD, Horiot JC, Nabid A. The development of a scale for the assessment of sexual functioning after treatment for gynecologic malignancy. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1984;2(1):23–19. [Google Scholar]

- Brotto LA, Erskine Y, Carey M, Ehlen T, Finlayson S, Heywood M, et al. A brief mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral intervention improves sexual functioning versus wait-list control in women treated for gynecologic cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 2012;125(2):320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotto LA, Heiman JR, Goff B, Greer B, Lentz GM, Swisher E, et al. A psychoeducational intervention for sexual dysfunction in women with gynecologic cancer. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37(2):317–329. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter J, Sonoda Y, Chi DS, Raviv L, Abu-Rustum NR. Radical trachelectomy for cervical cancer: Postoperative physical and emotional adjustment concerns. Gynecologic Oncology. 2008;111(1):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter J, Stabile C, Gunn A, Sonoda Y. The physical consequences of gynecologic cancer surgery and their impact on sexual, emotional, and quality of life issues. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2013;10(Suppl 1):21–34. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RM, Sutcliffe SB, Malpas JS. Cytotoxic-induced ovarian failure in Hodgkin's disease. II. Effects on sexual function. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1979;242(17):1882–1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton AH, Segraves RT, Leiblum S, Basson R, Pyke R, Cotton D, et al. Reliability and validity of the Sexual Interest and Desire Inventory-Female (SIDI-F), a scale designed to measure severity of female hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2006;32(2):115–135. doi: 10.1080/00926230500442300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona G, Jannini EA, Maggi M. Inventories for male and female sexual dysfunctions. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2006;18:236–250. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton EJ, Rasmussen VN, Classen CC, Grumann N, Palesh OG, Zarcone J, et al. Sexual Adjustment and Body Image Scale (SABIS): A new measure for breast cancer patients. The Breast Journal. 2009;15(3):287–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00718.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deixonne B, Baumel H, Domergue J. Les troubles sexuels après amputation abdominopérinéale du rectum. [Sexual disorders after abdominoperineal amputation of the rectum] Annales de Chirguries. 1982;36(7):475–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Melo Ferreira AP, de Figueiredo EM, Lima RA, Cãndido EG, de Castro Monteiro MV, de Figueiredo Franco TM, et al. Quality of life in women with vulvar cancer submitted to surgical treatment: A comparative study. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 2012;165(1):91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The DSFI: A multidimensional measure of sexual functioning. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 1979;5(3):244–281. doi: 10.1080/00926237908403732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSimone M, Spriggs E, Gass JS, Carson SA, Krychman ML, Dizon DS. Sexual dysfunction in female cancer survivors. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;37(1):101–106. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318248d89d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizon DS, Suzin D, McIlvenna S. Sexual health as a survivorship issue for female cancer survivors. Oncologist. 2014;19(2):202–210. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn KE, Lin L, Cyranowski JM, Reeve BB, Reese JB, Jeffery DD, et al. Development of the NIH PROMIS ® Sexual Function and Satisfaction measures in patients with cancer. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2013;10(Suppl 1):43–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein I, Fisher WA, Sand M, Rosen RC, Mollen M, Brock G, et al. Women's sexual function improves when partners are administered vardenafil for erectile dysfunction: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2005;2(6):819–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald HP, McCorkle R. Sexuality and sexual function in long-term survivors of cervical cancer. Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(6):955–963. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery DD, Tzeng JP, Keefe FJ, Porter LS, Hahn EA, Flynn KE, et al. Initial report of the cancer Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) sexual function committee: Review of sexual function measures and domains used in oncology. Cancer. 2009;115(6):1142–1153. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PT, Klee MC, Thranov I, Groenvold M. Validation of a questionnaire for self-assessment of sexual function and vaginal changes after gynaecological cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13(8):577–592. doi: 10.1002/pon.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juraskova I, Jarvis S, Mok K, Peate M, Meiser B, Cheah BC, et al. The acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy (phase I/II study) of the OVERcome (Olive Oil, Vaginal Exercise, and Moisturize R) intervention to improve dyspareunia and alleviate sexual problems in women with breast cancer. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2013;10(10):2549–2558. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahanpää V, Gylling T. Über den Zustand der mit Strahlenbehandlung geheilten Kollumkarzinompatientinnen bezüglich des Geschlechts. [State of sexual life in women cured from cervical carcinoma by irradiation] Annales Chirurgiae et Gynaecologiae Fenniae. 1951;40(3):189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasry J-CM, Margolese RG, Poisson R, Shibata H, Fleischer D, Lafleur D, et al. Depression and body image following mastectomy and lumpectomy. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40:529–534. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Borgne G, Mercier M, Woronoff AS, Guizard AV, Abeilard E, Caravati-Jouvenceaux A, et al. Quality of life in long-term cervical cancer survivors: A population-based study. Gynecologic Oncology. 2013;129(1):222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz TA, Stephenson KR, Meston CM. Validated questionnaires in female sexual function assessment, Chapter 21. In: Mulhall JP, Incrocci L, Goldstein I, Rosen R, editors. Cancer and Sexual Health. New York, NY: Series: Current Clinical Urology, Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; 2011. [Accessed September 2, 2014]. Available at URL: http://homepage.psy.utexas.edu/HomePage/Group/MestonLAB/Publications/TierneyKyleChapter.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mantegna G, Petrillo M, Fuoco G, Venditti L, Terzano S, Anchora LP, et al. Long-term prospective longitudinal evaluation of emotional distress and quality of life in cervical cancer patients who remained disease-free 2-years from diagnosis. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGahuey CA, Gelenberg AJ, Laukes CA, Moreno FA, Delgado PL, McKnight KM, et al. The Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX): Reliability and validity. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2000;26(1):25–40. doi: 10.1080/009262300278623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlone ER, Khan O, Flashman K, Khan J, Parvaiz A. Urogenital function following laparoscopic and open rectal cancer resection: A comparative study. Surgical Endoscopy. 2012;26(9):2559–2565. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minig L, Vélez JI, Trimble EL, Biffi R, Maggion iA, Jeffery DD. Changes in short-term health-related quality of life in women undergoing gynecologic oncologic laparotomy: an associated factor analysis. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21(3):715–726. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1571-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro-Valdezate D, Peiró S, Buch-Villa E, Caballero-Gárate A, Morales-Monsalve MD, Martinez-Aquiló A, et al. Evolution of health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients during the first year of follow-up. Journal of Breast Cancer. 2013;16(1):104–111. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2013.16.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Yoon HG. Menopausal symptoms, sexual function, depression, and quality of life in Korean patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21(9):2499–2507. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1815-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse QD, Kenter GG, Maas CP, de Kroon CD, Creutzberg CL, Trimbos GB, et al. Self-reported sexual, bowel and bladder function in cervical cancer patients following different treatment modalities: longitudinal prospective cohort study. International. Journal of Gynecologic Cancer. 2013;23(9):1717–1725. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182a80a65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRISMA: Transparent reporting of Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. [Accessed February 12, 2015]; (n.d.), Retrieved from http://www.prisma-statement.org/ [Google Scholar]

- PROsetta Stone®. [Accessed February 12, 2015]; (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.prosettastone.org. [Google Scholar]

- Psoter WJ, Aguilar ML, Levy A, Baek LS, Morse DE. A preliminary study on the relationships between global health/quality of life and specific head and neck cancer quality of life domains in Puerto Rico. Journal of Prosthodontics. 2012;21(6):460–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2012.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezk YA, Hurley KE, Carter J, Dao F, Boachner BH, Aubey JJ, et al. A prospective study of quality of life in patients undergoing pelvic exenteration: Interim results. Gynecologic Oncology. 2013;128(2):191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen RC. Assessment of female sexual dysfunction: review of validated methods. Fertility and Sterility. 2002;77(Suppl 4):S89–S93. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)02966-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust J, Golombok S. The GRISS: A psychometric instrument for the assessment of sexual dysfunction. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1986;15(2):157–165. doi: 10.1007/BF01542223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk FH, Heiman JR, Rosen RC, Laa nE, Smith MD, Boolell M. Development of a sexual function questionnaire for clinical trials of female sexual dysfunction. Journal of Women’s Health and Gender-based Medicine. 2002;11(3):277–289. doi: 10.1089/152460902753668475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JF, Rosen RC, Leiblum SR. Self-report assessment of female sexual function: Psychometric evaluation of the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1994;23(6):627–643. doi: 10.1007/BF01541816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]