Abstract

Chlamydia replication requires host lipid acquisition, allowing flow cytometry to identify C. trachomatis-infected cells that accumulated fluorescent Golgi-specific lipid. Herein, we describe modifications to currently available methods that allow precise differentiation between uninfected and C. trachomatis-infected human endometrial cells and rapidly and accurately quantify chlamydial inclusion forming units.

Keywords: Chlamydia trachomatis, ceramide, flow cytometry, human endometrial cells, inclusion forming units

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular Gram-negative bacterium infecting human ocular and genital epithelial cells, whose dissemination into the female upper genital can cause pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility [reviewed in Chavez et al., 2011]. Similar to other Chlamydia spp., C. trachomatis forms parasitophorous vacuoles (“chlamydial inclusions”) in infected cells, and needs to acquire host lipids from post-Golgi vesicles to support inclusion growth and bacterial replication (Hackstadt et al., 1995; Boleti et al., 2000; Wolf and Hackstadt, 2001; Heuer et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2012). Exploiting the requirement of Chlamydia to acquire lipids to replicate, a prior study utilized a 2-3h in vitro incubation with fluorescent, Golgi-specific lipid to subsequently distinguish between uninfected and Chlamydia-infected McCoy cells by flow cytometry (Alzhanov et al., 2006). Using the described methodology, we could not identify which human endometrial cells had been infected in vitro with C. trachomatis (Fig. 1A, upper panels). When altering the fluorescent ceramide probe concentration failed to correct this problem (data not shown), we speculated ceramide uptake was compromised by a propensity of endometrial cell lines to form in vitro aggregates (similar to other human genital epithelial cell lines). Alternatively, it was possible that longer incubations were needed for uninfected cells to lose sufficient amounts of the fluorescent label (via transport from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane) to allow flow cytometric analysis to discriminate between uninfected and C. trachomatis-infected cells.

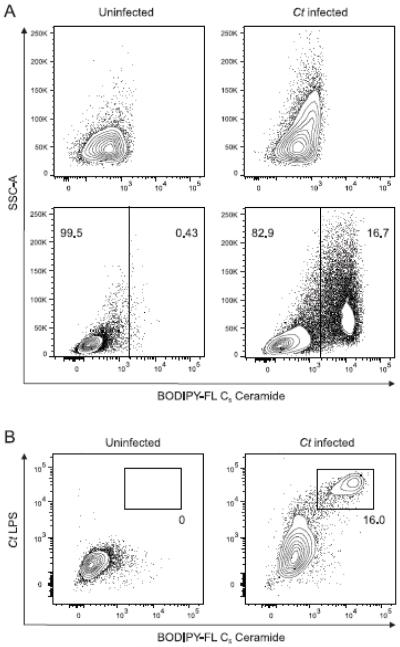

Fig. 1. Developing methodology that clearly identifies Chlamydia trachomatis in living human endometrial cells.

A) 24h after ECC-1 endometrial carcinoma cells were infected with C. trachomatis serovar D (MOI = 0.5), they were labeled with BODIPY-FL C5 ceramide using a previously described protocol for detection of Chlamydia-infected McCoy cells or a modification of this protocol. Though the original method inadequately separated populations of uninfected (control) and infected cells (upper panels), our modifications allowed unequivocal distinction between uninfected (control) and C. trachomatis-infected ECC-1 cells (lower panels). Representative contour plots displayed are from one of 9 independent experiments performed. B) Combined use of our modified protocol and intracellular chlamydial inclusion staining with an anti-Chlamydia LPS monoclonal antibody after permeabilization, confirmed specificity of fluorescent ceramide retention in C. trachomatis-infected ECC-1 cells. Representative contour plots shown are from one of 3 independent experiments performed. In each contour plot, numbers indicate percentages in each gate (Ct, C. trachomatis).

To explore these possibilities, about 1.25 x 105 ECC-1 endometrial carcinoma cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) in 2mL of RPMI 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 5% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA), L-glutamine, pyruvate, and non-essential amino acids (hereafter identified as complete medium) were added to individual wells of 24-well cluster plates and incubated for 24h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Complete medium was removed by aspiration, and cells washed with 0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM sodium phosphate, and 5 mM L-glutamic acid (i.e., SPG medium) or Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were infected with C. trachomatis serovar D (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) in 2mL of SPG medium or HBSS (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 0.5), and cluster plates centrifuged at 2,700xg for 30m at 15°C. SPG medium or HBSS was replaced with complete medium, and cultures incubated an additional 24h in complete medium. Cells were washed with PBS, and incubated with a 0.25% trypsin/EDTA solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10m at room temperature. Complete medium was added to inhibit trypsin activity, and cell suspensions transferred to 14mL polystyrene snap cap tubes containing 5mL HBSS. Cells were centrifuged at 300xg for 5m, and re-suspended in HBSS. The single-cell suspensions were incubated in 2mL of 0.5µM N-(4,4-Difluoro-5,7-Dimethyl-4-Bora-3a,4a-Diaza-s-Indacene-3-Pentanoyl) sphingosine (BODIPY-FL C5 Ceramide) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in HBSS at 37°C for 20m (tubes were placed on an orbital shaker at 200 RPM during this incubation to promote uniform fluorescent ceramide probe uptake). Cells were washed twice with complete medium, placed into individual wells of 24-well cluster plates, and incubated another 16h. Cultures were detached with trypsin/EDTA solution, complete medium added, and cell suspensions transferred to microcentrifuge tubes. After tubes were centrifuged at 300xg for 2m, cells were washed with PBS and re-suspended in 200µL FACS buffer (0.2% FBS in PBS) containing 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD; BioLegend, San Diego, CA) for flow cytometric analysis of ECC-1 cells viability and retention of the fluorescent ceramide probe. Cells were collected with a LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), and data analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

The modifications to existing methods (i.e., loading single-cell suspensions rather than adherent cells with a fluorescent ceramide probe and incubating such cells for 16h rather than 2-3h) allowed flow cytometric analysis to readily distinguish between uninfected (control) and C. trachomatis-infected endometrial cells (Fig. 1A, lower panels). In addition to the modified cell labeling procedure, cells were stained with LIVE/DEAD Fixable Near-IR (Thermo Fisher Scientific), fixed with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences), permeabilized with Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences), and stained with an unconjugated monoclonal antibody specific for Chlamydia lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (BDI168; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and an AF488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific). This additional step thus delivered confirmation our methodology had correctly identified C. trachomatis-infected human endometrial cells (Fig. 1B), without need for prior genetic manipulation of the bacteria.

Chlamydia trachomatis ascension into upper genital tract tissue plays an important role in pelvic inflammatory disease pathogenesis (Reighard et al., 2011), and this newly demonstrated stability of BODIPY-FL C5 ceramide in Chlamydia-infected human endometrial cells after a 16h incubation, fixation and permeabilization procedures should foster more comprehensive phenotypic evaluation of Chlamydia-infected cells and help elucidate how C. trachomatis promotes genital tract damage. Moreover, as our methodology can likely be used to interrogate any cell types permissive to productive C. trachomatis infection, other potential applications include cell sorting for cloning, gene expression analysis, and other downstream applications.

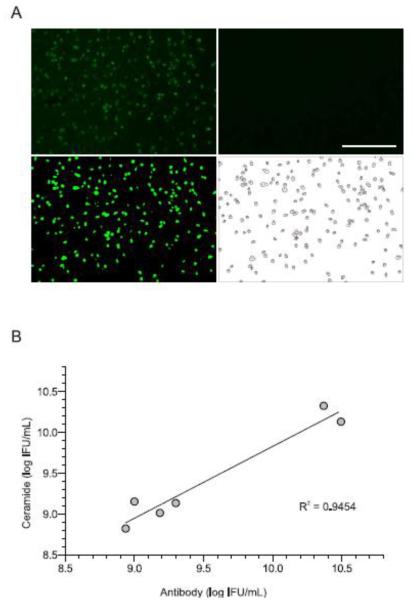

Once we resolved the revised methods could identify C. trachomatis-infected human endometrial cells, McCoy cell cultures (i.e., cells adherent to cluster plate wells and not in single-cell suspension) were administered the same fluorescent ceramide probe 24h after infection with serial dilutions of C. trachomatis serovar D stocks with known IFU titers, and provided the same extended 16h incubation. Cells were washed with PBS, and fixed with 2% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich). Analogous to our flow cytometry data with ECC-1 cells, fluorescent microscopic images captured with an EVOS® FL Cell Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) readily distinguished between uninfected and C. trachomatis-infected McCoy cells (Fig. 2A). Subsequent data analysis with ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012) also rapidly quantified the number of McCoy cells in each culture that contained chlamydial inclusions (Fig. 2A), while direct side-by-side comparison of our results with conventional quantification of Chlamydia inclusion forming units (IFU) with anti-Chlamydia LPS antibody (Scidmore, 2005) revealed substantial correlation between these 2 methods (Fig. 2B). However, because fluorescent ceramide labeling of chlamydial inclusions and ImageJ software analysis quantified C. trachomatis-infected cells more rapidly and less expensively than use of anti-Chlamydia LPS antibody, our modifications identified an attractive new method for chlamydial IFU calculation.

Fig. 2. Using the revised method to rapidly and accurately quantify chlamydial inclusion forming units (IFU).

A) McCoy cells plated in 96-well plates were not infected (right upper panel), used as controls, or infected with serial dilutions of C. trachomatis serovar D stocks with known IFU titers (left upper panel, one dilution shown). 24h later all cells were labeled with BODIPY-FL C5 ceramide. After 16h incubation, cell images were captured at a 100x magnification using a fluorescent microscope (scale bar, 400µm). ImageJ software analysis was used to adjust the threshold identifying infected cells (left lower panel), and define number of inclusions per field using the analyze particles command (right lower panel). Representative images shown are from one of 6 independent experiments. B) Linear regression analysis identified a strong correlation between C. trachomatis IFU titers calculated from traditional anti-Chlamydia LPS antibody methodology vs. methodology using fluorescent ceramide labeling of intracellular chlamydial inclusions.

Highlights.

Chlamydia trachomatis replication requires acquisition of host lipids

Flow cytometry is used to detect Chlamydia-infected cells accruing fluorescent ceramide

By modifying this method, we identified C. trachomatis-infected human endometrial cells

This modification also allowed precise calculation of chlamydial inclusion forming units

Modified method should expedite phenotypic evaluation of C. trachomatis-infected cells

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Paul Stoodley and Dr. Luanne Hall Stoodley for providing fluorescent microscopy support and Dr. Ann Thompson for thoughtful dialogue. The National Institute of Child and Human Development (grant R01HD072663) and The Ohio State University College of Medicine provided support for this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alzhanov DT, Suchland RJ, Bakke AC, Stamm WE, Rockey DD. Clonal isolation of chlamydia-infected cells using flow cytometry. J. Microbiol. Meth. 2007;69:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boleti H, Ojcius DM, Dautry-Varsat A. Fluorescent labelling of intracellular bacteria in living host cells. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2000;40:265–274. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(00)00132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez JM, Vicetti Miguel RD, Cherpes TL. Chlamydia trachomatis infection control programs: lessons learned and implications for vaccine development. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 20112011:754060. doi: 10.1155/2011/754060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AL, Johnson KA, Lee JK, Sütterlin C, Tan M. CPAF: a chlamydial protease in search of an authentic substrate. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002842. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackstadt T, Scidmore MA, Rockey DD. Lipid metabolism in Chlamydia trachomatis infected cells: directed trafficking of Golgi-derived sphingolipids to the chlamydial inclusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:4877–4881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer D, Rejman Lipinski A, Machuy N, Karlas A, Wehrens A, Siedler F, Brinkmann V, Meyer TF. Chlamydia causes fragmentation of the Golgi compartment to ensure reproduction. Nature. 2009;457:731–735. doi: 10.1038/nature07578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reighard SD, Sweet RL, Vicetti Miguel C, Vicetti Miguel RD, Chivukula M, Krishnamurti U, Cherpes TL. Endometrial leukocyte subpopulations associated with Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis genital tract infections. Amer. J. Ob. Gyn. 2011;205:324e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scidmore MA. Cultivation and Laboratory Maintenance of Chlamydia trachomatis. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2005 doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc11a01s00. Chapter 11: Unit 11A.1. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc11a01s00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf K, Hackstadt T. Sphingomyelin trafficking in Chlamydia pneumonia-infected cells. Cell. Microbiol. 2001;3:145–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]