Abstract

Objective

Examine the association between thoughts of death or self harm reported on item 9 of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) depression module and the risk of suicide attempt or suicide death over the following two years

Methods

In four healthcare systems participating in the Mental Health Research Network, electronic records identified 509,945 adult outpatients completing 1,228,308 PHQ depression questionnaires during visits to primary care, specialty mental health, and other outpatient providers. Non-fatal suicide attempts (n=9,582) were identified using health system records of inpatient or outpatient encounters for self-inflicted injury. Suicide deaths (n=484) were identified using cause-of-death codes from state mortality data.

Results

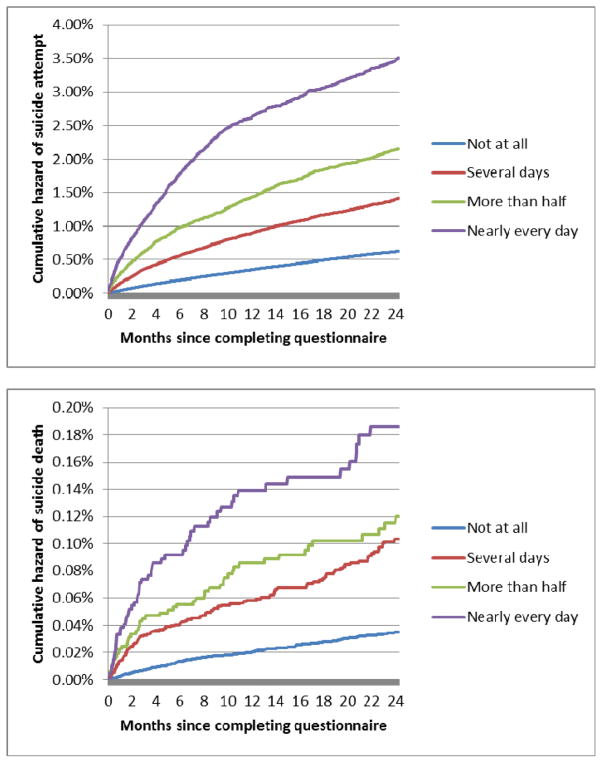

Cumulative hazard of suicide attempt over two years ranged from approximately 0.5% among those reporting thoughts of death or self harm “not at all” to 3.5% among those reporting such thoughts “nearly every day”. Cumulative hazard of suicide death over two years ranged from approximately 0.04% among those responding “not at all” to 0.19 % among those responding “nearly every day”. The excess hazard associated with thoughts of death or self-harm declined with time, but remained statistically significant and clinically important for at least 18 months. Nevertheless, 39% of suicide attempts and 36% of suicide deaths within 30 days of completing a PHQ occurred among those responding “not at all” to item 9.

Conclusions

In community practice, response to PHQ item 9 is a strong predictor of suicide attempt and suicide death over the following two years. For patients reporting thoughts of death or self-harm, suicide prevention efforts must address this enduring vulnerability.

Suicide remains the 10th-ranked cause of death in the US, accounting for 41,000 deaths in 2013 (1). Suicide attempts lead to 600,000 emergency department visits (2) and 200,000 hospitalizations (3) annually in the US. Effective suicide prevention will require accurate identification of those at risk. In 2013, the US Preventive Services Task Force (4) found only “minimal evidence suggesting that some screening tools can identify some adults at increased risk for suicide in primary care.”

Since the publication of the Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, we reported (5) that the ninth question of the commonly used Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) depression module can accurately identify outpatients at increased risk of suicide attempt and death by suicide. Mental health and primary care patients reporting frequent thoughts of death or self-harm were six times as likely to attempt suicide and five times as likely to die by suicide over the following year, compared to those not reporting such thoughts.

Increasing use of the PHQ and similar self-report scales in community practice (6–8) creates both a need and an opportunity to understand how self-reported suicidal ideation predicts suicidal behavior. Clinicians using these questionnaires will need guidance regarding the immediate and long-term risk associated with thoughts of death or self-harm. Large health records databases allow us to address that question.

Here we use data from approximately 500,000 patients in four health systems to examine the relationship between self-reported thoughts of death or self-harm and subsequent suicidal behavior. We focus on three questions: Are the relationships reported previously from a single health system replicated in this larger and more diverse sample? What is the immediate risk of suicidal behavior among outpatients reporting thoughts of death or self-harm? How does the risk associated with response to PHQ item 9 change over time?

METHODS

Data are drawn from four health systems in the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN), a National Institute of Mental Health-funded consortium of research centers based in large integrated healthcare systems. Across these systems, electronic medical records and insurance claims have been organized in a Virtual Data Warehouse to facilitate population-based research (9). Protected health information remains at each system, but common data definitions and formats facilitate sharing of de-identified data for research. Institutional Review Boards and privacy boards at each health system approved use of de-identified data for this research.

The four MHRN health systems contributing data to this report include Group Health Cooperative, HealthPartners, Kaiser Permanente of Colorado and Kaiser Permanente of Southern California. These health systems recommend routine use of the PHQ in depression care visits and routinely record E-code (or cause-of-injury) diagnoses, allowing ascertainment of suicide attempts. These systems serve a combined population of approximately 5 million patients in California, Colorado, Minnesota, Washington, and Idaho. Patients are generally representative of each system’s geographic area, and are enrolled through a mixture of employer-sponsored insurance, individual insurance, capitated Medicare and Medicaid programs, and other state-subsidized low-income programs.

The PHQ depression module (often referred to as the PHQ-9) begins with the general instruction “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems?” The ninth item asks about “Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way” with response options including “Not at all”, “Several days”, “More than half the days”, and “Nearly every day”.

The study sample included all PHQ results in electronic medical records between 1/1/2007 and 12/31/2012. Any individual patient could contribute multiple PHQ observations. Suicide deaths were identified using cause-of-death data from state death certificate files. Deaths were classified as due to suicide if ICD-10 cause-of-death codes indicated definite (X60 to X84) or possible (Y10 through Y34) self-inflicted injury. Death certificate data were available through 12/31/2012. Nonfatal suicide attempts were identified using electronic medical records (for services provided at health system facilities) and insurance claims (for services provided by external providers or facilities). These data were available through 12/31/2013. Three criteria were used to identify non-fatal suicide attempts:

ICD-9 diagnosis of self-inflicted injury or poisoning (E950 through E958)

ICD-9 diagnosis of injury or poisoning considered possibly self-inflicted (E980 through E988)

ICD-9 diagnosis of suicidal ideation (V62.84) accompanied by a diagnosis of either poisoning (960 through 989) or open wound (870 through 897).

We previously reported (5, 10, 11) that validation by clinician review of 200 full-text medical records found a positive predictive value of 100% for the first criterion, 80% for the second, and 86% for the third (compared to treating providers’ documentation of self-inflicted injury with suicidal intent). Given the relative frequency of these three criteria in our sample, we estimate the weighted average positive predictive value to be 94% for all three combined.

The proportion of medically treated suicide attempts that might be missed by this method was estimated by examining the proportion of emergency department and hospital encounters for injury or poisoning in which a cause-of-injury code (or E-code) was not recorded (12). In 2010, the proportion of injury or poisoning encounters with no E-code ranged from 11 to 26% in these four health systems (13).

Descriptive analyses examined risk of suicide attempt (nonfatal or fatal) and suicide death following completion of a PHQ, stratified by response to item 9. Analyses of long-term risk accounted both for multiple PHQ observations per person and for censoring of availability of outcome data over time. Each new questionnaire defined a new period at risk, and a patient could contribute multiple overlapping risk periods by completing multiple PHQs. Each suicide attempt or death could be linked to multiple prior PHQ results from a single patient. This approach examines risk based on data available when the PHQ was completed, regardless of subsequent questionnaires. It avoids informative censoring that would occur if likelihood of completing a later PHQ was related to risk of a subsequent suicide attempt. For analyses of suicide attempts, each risk period was censored at the time of disenrollment from the health system, death from causes other than suicide, or last availability of suicide attempt data. For analyses of suicide deaths, each risk period was censored at the time of disenrollment from the health system, death from causes other than suicide, or last availability of suicide death data. Because predictors of repeat suicide attempts may differ from first attempts, PHQ9 observations following a suicide attempt were excluded from analyses of suicide attempts.

Partly conditional Cox proportional hazards regression (14) was used to estimate the association between response to PHQ item 9 and subsequent suicide attempt or death after accounting for potential confounders (age, sex, and health system). Estimated hazard associated with responding “nearly every day”, “more than half the days”, and “several days” was compared to estimated hazard associated with responding “not at all” (the reference group). Because each individual patient could contribute multiple PHQ responses, the robust sandwich estimator (15) was used to calculate confidence limits for hazard ratio estimates. To examine how the relationship between response to item 9 and hazard of subsequent suicidal behavior did or did not decrease over time, we compared alternative models including either a constant effect of item 9 response over time or two possible time-varying effects: a linear decrease or a log-linear decrease over time. Alternative models were evaluated using the Bayesian Information Criterion statistic (16, 17); a decrease of ten points is considered a meaningful improvement in model fit.

RESULTS

After applying the above eligibility criteria and exclusions, electronic medical records contained 1,228,308 PHQ results for 509,945 patients, including 302,659 patients (59%) with a single questionnaire, 95,880 (19%) with two, 38,321 (8%) with three, 20,204 (4%) with four, and 52,881 (10%) with five or more. Encounters in which questionnaires were administered included 500,751 (41%) with specialty mental health providers, 442,509 (36%) with primary care providers, and 285,048 (23%) with various other medical or surgical specialists (including emergency department visits). At time of completing the PHQ, 709,580 (58%) had received some mental health diagnosis or treatment in the previous 90 days. Using the conventional classification of PHQ scores, depression was minimal (score 0 to 4) in 408,575 (34%), mild (score 5 to 9) in 295,907 (25%), moderate (score 10 to 14) in 221,845 (19%), moderately severe (score 15 to 19) in 153,946 (13%), and severe (20 or greater) in 103,098 (9%). As shown in Table 1, patients completing PHQs were predominantly female and were diverse with respect to age and race/ethnicity. Approximately 3.5% reported thoughts of death or self-harm “more than half the days” and approximately 2.4% reported such thoughts “nearly every day”, but these proportions varied according to age and race/ethnicity.

Table 1.

Distribution of responses to PHQ item 9 according to patients’ sociodemographic characteristics. Table cells report number of PHQ observations and row percentages.

| Not at all | Several days | More than half the days | Nearly every day | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 271,060 (79%) | 46,646 (14%) | 15,523 (5%) | 9,969 (3%) | 343,198 |

| Female | 752,843 (85%) | 85,127 (10%) | 27,971 (3%) | 19,169 (2%) | 885,110 |

| Age | |||||

| 18–29 | 211,608 (85%) | 23,823 (10%) | 7,706 (3%) | 4,746 (2%) | 247,883 |

| 30–44 | 295,915 (85%) | 33,683 (10%) | 11,032 (3%) | 7,098 (2%) | 347,728 |

| 45–64 | 342,368 (80%) | 55,156 (13%) | 18,812 (4%) | 12,693 (3%) | 429,029 |

| 65+ | 174,012 (85%) | 19,111 (9%) | 5,944 (3%) | 4,601 (2%) | 203,668 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White, not Hispanic | 658,486 (82%) | 93,898 (12%) | 29,735 (4%) | 19,596 (2%) | 801,715 |

| Asian | 52,647 (87%) | 5,073 (8%) | 1,783 (3%) | 1,010 (2%) | 60,513 |

| Black | 67,764 (83%) | 7,773 (10%) | 3,333 (4%) | 2,289 (3%) | 81,159 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 4,920 (83%) | 582 (10%) | 227 (4%) | 219 (4%) | 5,948 |

| Native American | 11,339 (79%) | 1,821 (13%) | 699 (5%) | 541 (4%) | 14,400 |

| Hispanic | 174,585 (89%) | 13,013 (7%) | 4,407 (2%) | 3,287 (2%) | 195,292 |

| Other or Unknown | 54,162 (78%) | 9,613 (14%) | 3,310 (5%) | 2,196 (3%) | 69,281 |

In this sample, death certificate data identified 484 suicide deaths, including 457 attributed to definite self-inflicted injury and 27 attributed to possible self-inflicted injury.

Electronic medical records and insurance claims data identified 9203 unique instances of non-fatal suicide attempt, limited to the first attempt per person. These included 6,345 diagnoses of definite self-inflicted injury, an additional 2,105 diagnoses of possible self-inflicted injury, and an additional 753 probable suicide attempts identified by the combination of a poisoning or wound diagnosis linked to a diagnosis of suicidal ideation.

Table 2 describes counts and rates of suicide attempts and deaths in 7 days and 30 days after completing a PHQ. While rates of suicide attempt and suicide death increased with escalating responses to PHQ item 9, over one third of suicide attempts and suicide deaths occurred among those responding “not at all”. Even among those reporting thoughts of death or self-harm nearly every day, risk of any suicide attempt within 7 days was approximately 1 in 500 and risk of suicide death was approximately 1 in 10,000.

Table 2.

Counts and rates of suicide attempts and suicide deaths with 7 and 30 days of completing PHQ questionnaire

| Non-fatal or Fatal Suicide Attempt | Suicide Death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 9 Response | # of PHQ Reponses | Within 7 Daysa | Within 30 Daysb | # of PHQ Reponses | Within 7 Daysc | Within 30 Daysd |

| Not at all | 1,023,903 | 119 (0.012%) | 447 (0.044%) | 827,194 | 8 (<0.001%) | 28 (0.003%) |

| Several days | 131,773 | 77 (0.058%) | 290 (0.220%) | 106,434 | 3 (0.003%) | 24 (0.022%) |

| More than half the days | 43,494 | 60 (0.138%) | 188 (0.432%) | 35,793 | 4 (0.011%) | 13 (0.036%) |

| Nearly every day | 29,138 | 62 (0.213%) | 220 (0.755%) | 24,316 | 2 (0.008%) | 13 (0.053%) |

| Total | 1,228,308 | 318 (0.026%) | 1,145 (0.093%) | 993,737 | 17 (0.002%) | 78 (0.008%) |

Notes:

X2 for comparison of proportions = 738, df=3, p<.0001

X2 for comparison of proportions = 2405, df=3, p<.0001

X2 for comparison of proportions = 28, df=3, p<.0001

X2 for comparison of proportions = 152, df=3, p<.0001

The estimated long-term hazard of any suicide attempt (nonfatal or fatal) stratified by response to PHQ item 9 is shown in the top half of Figure 1. Over two years, cumulative hazard ranged from approximately 0.5% (1 in 200) for those responding “not at all” to approximately 3.5% (1 in 30) for those responding “nearly every day”.

Figure 1.

Cumulative hazard of any suicide attempt and suicide death over two years according to response to PHQ item 9 regarding thoughts of death or self-harm.

In a partly conditional Cox proportional hazards model predicting risk of any suicide attempt, addition of item 9 response (three indicator variables for levels of positive response) was a highly significant predictor of average risk over two years (p<.00001 compared to model including only age, sex and study site). Allowing the effect of item 9 responses to vary linearly over time significantly improved model fit (Bayesian Information Criterion or BIC decreased from 255,003 to 254,813). Model fit was further improved by allowing the effect of item 9 responses to vary over time in a log-linear fashion (BIC decreased to 254,786). Table 3 displays the estimated relative hazards of suicide attempt from the final model allowing a log-linear change over time. The excess hazard associated with reporting thoughts of death or self-harm did decrease over time, but relative hazards for all positive responses remained significantly elevated through 18 months.

Table 3.

Estimated relative hazards of suicide attempt or suicide death (with 95% confidence interval) according to response to PHQ item 9 and time since completion of questionnaire. Model allows log-linear change in relative hazard over time and includes adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity and health system.

| 30 days | 90 days | 180 days | 360 days | 540 days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANY SUICIDE ATTEMPT | |||||

| Not at all | [Reference] | [Reference] | [Reference] | [Reference] | [Reference] |

| Several days | 3.2 (2.9–3.6) | 2.6 (2.4–2.9) | 2.3 (2.1–2.5) | 2.0 (1.9–2.3) | 1.9 (1.7–2.1) |

| More than half the days | 5.8 (5.0–6.6) | 4.3 (3.8–4.8) | 3.5 (3.1–4.0) | 2.9 (2.5–3.4) | 2.6 (2.2–3.1) |

| Nearly every day | 10.3 (8.8–12.1) | 7.3 (6.3–8.5) | 5.9 (5.0–6.9) | 4.7 (3.9–5.7) | 4.2 (3.4–5.1) |

| SUICIDE DEATH | |||||

| Not at all | [Reference] | [Reference] | [Reference] | [Reference] | [Reference] |

| Several days | 3.6 (2.5–5.3) | 3.1 (2.4–4.2) | 2.8 (2.1–3.8) | 2.6 (1.8–3.6) | 2.5 (1.7–3.6) |

| More than half the days | 5.3 (3.2–9.0) | 3.9 (2.4–6.5) | 3.2 (1.8–5.8) | 2.7 (1.3–5.4) | 2.4 (1.1–5.2) |

| Nearly every day | 8.5 (5.3–13.7) | 6.3 (4.1–9.7) | 5.2 (3.2–8.4) | 4.3 (2.5–7.6) | 3.9 (2.1–7.2) |

The estimated long-term hazard of suicide death according to item 9 response is shown in the bottom half of Figure 1. Over two years, cumulative hazard ranged from approximately 0.04% (1 in 2500) for those responding “not at all” to approximately 0.2% (1 in 500) for those responding “nearly every day”. No clear separation was observed between those responding “Several days” and “More than half the days”.

In a partly conditional Cox proportional hazards model predicting risk of suicide death by age, sex and study site, addition of three indicator variables for item 9 response was a significant predictor of average hazard over two years (p<0.0001). Table 3 displays the estimated relative hazard of suicide death for different responses to PHQ item 9, again allowing the effect of item 9 scores to vary over time in a log-linear fashion. Confidence limits were wider than those for relative hazard of suicide attempt, reflecting the smaller number of events. Estimated relative hazard associated with a response of “more than half the days” appear to decline more with time than seen for suicide attempts. No statistically significant differences were observed between the “Several days” and “More than half the days” groups at any time point. Otherwise, the overall pattern was generally similar to that seen for suicide attempts: relative hazard estimates declined over time but remained significantly elevated through 18 months.

The proportional hazards models described above were used to examine the unique contribution of item 9 to predicting suicidal behavior, over and above the effect of depression severity (as indicated by items 1 through 8). As shown in Table 4, adding categorical indicators for overall depression severity only slightly attenuated the excess hazard associated with response to item 9 for prediction of suicide attempts (column 2 vs column 3) or suicide deaths (column 4 vs. column 5).

Table 4.

Relative hazards suicide attempt or suicide death 30 days after completion of PHQ according to response to item 9. Columns 2 and 4 do not adjust for response to PHQ items 1 to 8; columns 3 and 5 also adjust for response to items 1 to 8.

| Relative hazard of any suicide attempt | Relative hazard of suicide death | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response to item 9 | ||||

| Not at all | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Several days | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 3.2 |

| More than half the days | 5.8 | 4.5 | 5.3 | 4.3 |

| Nearly every day | 10.3 | 7.9 | 8.5 | 6.7 |

| Score for items 1 to 8 | ||||

| 0 through 9 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 10 through 14 | 1.3 | 1.3 | ||

| 15 or more | 1.6 | 1.5 | ||

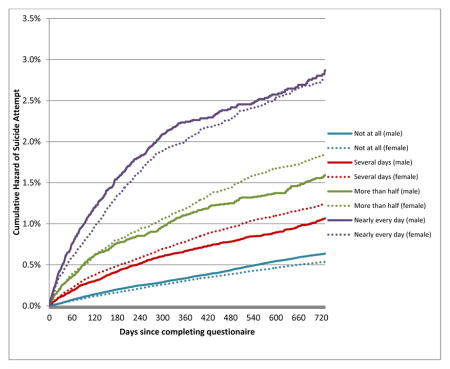

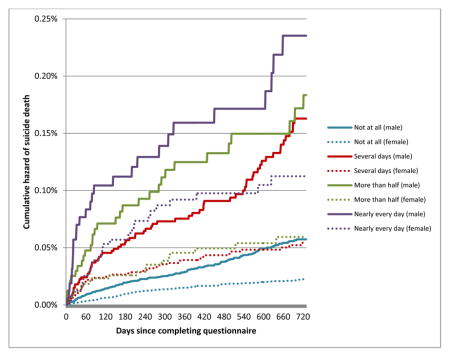

Analyses stratified by sex found that absolute hazard of suicide risk was higher in males, but relative hazard of suicide attempt and suicide death according to PHQ item 9 response was generally similar for males and females (see online Appendix for details).

DISCUSSION

In this sample of over 1.2 million PHQ depression questionnaires completed by over 500,000 outpatients, we find that response to PHQ item 9 was a strong predictor of suicide attempt and suicide death over the following two years. These results extend our previous findings in three significant ways. First, the strong association between item 9 response and subsequent suicidal behavior is confirmed in more diverse sample from four large healthcare systems (Figure 1). Second, we can more precisely describe the immediate risk of suicidal behavior, a significant concern for practicing clinicians (Table 2). Third, long-term follow-up data allow us to describe how risk evolves over time (Table 3).

These real-world data have several important strengths. The sample was not limited to research volunteers and included all PHQ responses in a large, diverse sample from community practice. Thoughts of death or self-harm were reported in real time rather than recalled months or years later. Suicide attempts and suicide deaths were recorded independently and prospectively. These results illustrate the potential for “big data” from electronic health records to accelerate research and inform quality improvement regarding suicide risk.

Diagnoses of self-inflicted injury, our primary criterion for identifying suicide attempts, may have included cases of self-inflicted injury without suicidal intent. Our chart review validation, however, found a positive predictive value of over 90% for provider-documented suicidal intent.

While frequent thoughts of death or self-harm were strongly associated with subsequent suicidal behavior, we should emphasize the trade-off between sensitivity (identifying all patients at risk) and positive predictive value (identifying those at highest risk). As shown in Table 2, any positive response to item 9 would have a sensitivity of 61% (698/1145) for detecting any suicide attempt and 64% (50/78) for detecting suicide death over one month. But the two-year cumulative hazard of suicide attempt in those with any positive response is less than 2%. Using a higher threshold of “more than half the days” or “nearly every day” would increase cumulative hazard or positive predictive value to approximately 3% but reduce sensitivity to approximately 35%. This trade-off is not unique to identifying suicide risk; it was described over 30 years ago concerning cardiovascular prevention (18). Interventions limited to those at highest risk will not reach the medium-risk population where most morbidity and mortality occur. For perspective, a 3% hazard of suicide attempt in outpatients with frequent thoughts of death or self-harm is similar to the hazard of stroke in outpatients with atrial fibrillation and hypertension (19).

The excess risk associated with reporting thoughts of death or self-harm did decrease with time. For example, the relative hazard of suicide attempt associated with reporting such thoughts “nearly every day” (compared to responding “not at all”) decreased from approximately ten to approximately four over 18 months. Relative hazard of suicide death showed a similar pattern of decrease over time. Nevertheless, reporting frequent thoughts of death or self-harm was associated with statistically significant and clinically important increases in risk of suicide attempt and suicide death for at least 18 months.

The PHQ was designed to assess depression severity, not to assess suicide risk. Broader questions regarding hopelessness or suicidal thoughts, such as those in the Beck Depression Inventory (20) or the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (21), might prove more sensitive. Questions focused on suicidal ideation, such as the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (22) or the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (23) might identify a smaller group at higher risk. At this time, we lack prospective data from community practice regarding those alternative assessments. We focus on the PHQ not because it is the optimal measure, but because it is widely used in community practice.

Most questionnaires in this sample were completed by patients receiving mental health treatment. Questions regarding thoughts of death or self-harm might have different meaning for patients with no mental health history. Our sample includes too few questionnaires from emergency departments or other specialty clinics to examine whether results differ in those specific settings. In most cases, treating clinicians were aware of PHQ responses and might be expected to take appropriate clinical actions to reduce risk. The association we observe between item 9 response and subsequent risk occurred in spite of any such clinical intervention.

Our findings certainly do not suggest that clinicians can use the PHQ or any other assessment to accurately predict short-term risk of suicidal behavior. Instead, we find that short-term prediction is not feasible and that emphasis on short-term risk is misplaced. Frequent thoughts of death or self-harm indicate an enduring vulnerability rather than simply a short-term crisis.

Any efforts to identify and reduce risk of suicidal behavior must be guided by evidence regarding risk levels in different populations. In the general population, where one-year risk of suicide attempt is less than one per thousand, community-level programs can increase public awareness or reduce availability of lethal means (24). At the other extreme, intensive programs (25, 26) focus on the small group of patients with recent or repeated suicide attempts, where one-year risk approaches one in two. Our findings suggest that responses to the commonly-used PHQ depression scale identify a large intermediate group for whom two-year risk of suicide attempt exceeds one in thirty. Additional research is needed to identify effective interventions appropriate for this at-risk group.

The Preventive Services Task Force recommendation against screening for suicide risk cited the absence of data regarding either the accuracy of screening tests or the effectiveness of preventive interventions. Our findings only address the first of those gaps. While our data cannot assess the effectiveness of interventions, they do provide guidance regarding timing of prevention programs. Among outpatients reporting thoughts or self-harm “nearly every day” cumulative hazard of suicide attempt was approximately 1 in 500 after one week, increasing to 1 in 30 over two years. Hospitalization or crisis-focused interventions may sometimes be necessary, but they cannot address risk that endures for months or years. Sustained interventions, most likely focused on skill development and maintaining treatment engagement, will be necessary to address sustained risk.

CLINICAL POINTS.

Reporting frequent thoughts of death or self-harm indicates a significant and sustained increase in risk of suicide attempt and suicide death.

Prevention efforts should address suicide risk as an enduring vulnerability rather than a short-term crisis.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Cooperative Agreement U19MH092201 with the National Institute of Mental Health. The funder (National Institute of Mental Health) was not involved in the design of the research, data analysis, interpretation, or preparation of this manuscript.

APPENDIX

The figure below shows cumulative hazard of any suicide attempt over two years according to response to PHQ item 9 regarding thoughts of death or self-harm. Different colors represent different responses to PHQ item 9. Solid lines show cumulative hazard for males and dashed lines show cumulative hazard for females.

Males and females show a generally similar pattern of increasing hazard with response to item 9 (i.e. generally similar RELATIVE hazard). For any level of item 9 response, the cumulative hazard is generally similar for males and females (i.e. generally similar ABSOLUTE hazard). In other words, we findings do not indicate a clinically or practically important main effect of sex OR interaction between sex and item 9 score in predicting subsequent risk of any suicide attempt.

Nevertheless, a formal test for interaction effect (test for heterogeneity of odds ratios for 3 indicator variables between two sex categories) is highly significant (p=.001). This “significant” interaction effect in the absence of a meaningful difference appears to reflect an “over-powered” interaction test (high level of precision due to large sample size and large number of suicide attempt events). Despite the significant test for interaction, we would conclude that the implications of response to PHQ item 9 for subsequent risk of any suicide attempt are generally similar for males and females

The figure below shows cumulative hazard of suicide death over two years according to response to PHQ item 9 regarding thoughts of death or self-harm. Different colors represent different responses to PHQ item 9. Solid lines show cumulative hazard for males and dashed lines show cumulative hazard for females.

Males and females show a generally similar pattern of increasing hazard with response to item 9 (i.e. generally similar RELATIVE hazard). But for any level of item 9 response, the cumulative hazard of suicide death is approximately twice as great in males (i.e. greater ABSOLUTE hazard). A formal test for interaction effect is not significant (p=.78), but we must acknowledge that (given the much smaller number of suicide deaths) this analysis is under-powered. The practical or clinical implications of these findings depend on whether we choose to focus on absolute or relative hazard. Regarding absolute hazard – Reporting frequent thoughts of death or self-harm implies approximately twice as much subsequent risk in males as in females. Regarding relative hazard – the proportional increase in risk associated with different levels of response to PHQ item 9 is generally similar for males and females (e.g. 8-fold increase in relative hazard after one month for response of “nearly every day” compared to “not at all”.)

Footnotes

Dr. Simon had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Original data in the HMORN Virtual Data Warehouse are owned by and remain under the control of the four participating healthcare systems. Investigators are allowed to access these data to address specific research questions – subject to specific approval by each health system’s Institutional Review Board and Privacy Board.

The authors have no relevant financial interests to disclose.

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics Reports. Hyattsville, MD: 2015. Deaths: Final Data for 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2008 Emergency Department Summary Tables. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. updated January 6, 2012; cited 2012 February 22, 2012 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/nhamcsed2008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crosby AE, Han B, Ortega LAG, Parks SE, Gfronerer J. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adults aged > 18 years - United States, 2008–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(13):1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connor E, Gaynes BN, Burda BU, Soh C, Whitlock EP. Screening for and treatment of suicide risk relevant to primary care: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(10):741–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-10-201305210-00642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, Oliver M, Whiteside U, Operskalski B, Ludman EJ. Does Response on the PHQ-9 Depression Questionnaire Predict Subsequent Suicide Attempt or Suicide Death? Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(12):1195–202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harding KJ, Rush AJ, Arbuckle M, Trivedi MH, Pincus HA. Measurement-based care in psychiatric practice: a policy framework for implementation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1136–43. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10r06282whi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kendrick T, Dowrick C, McBride A, Howe A, Clarke P, Maisey S, Moore M, Smith PW. Management of depression in UK general practice in relation to scores on depression severity questionnaires: analysis of medical record data. Bmj. 2009;338:b750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valuck RJ, Anderson HO, Libby AM, Brandt E, Bryan C, Allen RR, Staton EW, West DR, Pace WD. Enhancing Electronic Health Record Measurement of Depression Severity and Suicide Ideation: A Distributed Ambulatory Research in Therapeutics Network (DARTNet) Study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(5):582–93. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.05.110053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross TR, Ng D, Brown JS, Pardee R, Hornbrook MC, Hart G, Steiner JF. The HMO Research Network Virtual Data Warehouse: A Putlic Data Model to Support Collaboration. eGEMs. 2014;2(1) doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon G, Savarino J, Operskalski B, Wang P. Suicide risk during antidepressant treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:41–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon GE, Savarino J. Suicide attempts among patients starting depression treatment with medications or psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7):1029–34. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon G, Savarino J. Suicide attempts among patients starting depression treatment with medication or psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu CY, Stewart C, Ahmed AT, Ahmedani BK, Coleman K, Copeland LA, Hunkeler EM, Lakoma MD, Madden JM, Penfold RB, Rusinak D, Zhang F, Soumerai SB. How complete are E-codes in commercal plan claims databases? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:218–20. doi: 10.1002/pds.3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng Y, Heagerty PJ. Partly conditional survival models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 2005;61(2):379–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin DY, Wei LJ. The robust inference for the proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84:1074–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes Factors. J Am Stat Assoc. 1995;90:773–95. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volinsky CT, Raftery AE. Bayesian information criterion for censored survival models. Biometrics. 2000;56(1):256–62. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose G. Strategy of prevention: lessons from cardiovascular disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981;282(6279):1847–51. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6279.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer DE, Albers GW, Dalen JE, Fang MC, Go AS, Halperin JL, Lip GY, Manning WJ American College of Chest P. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition) Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):546S–92S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck AT, Beamesderfer A. Assessment of depression: the depression inventory. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1974;7(0):151–69. doi: 10.1159/000395074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, Markowitz JC, Ninan PT, Kornstein S, Manber R, Thase ME, Kocsis JH, Keller MB. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, Mann JJ. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA, Dahlsgaard KK, Grisham JR. Suicide ideation at its worst point: a predictor of eventual suicide in psychiatric outpatients. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1999;29(1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hegerl U, Lonnqvist J, Malone K, Marusic A, Mehlum L, Patton G, Phillips M, Rutz W, Rihmer Z, Schmidtke A, Shaffer D, Silverman M, Takahashi Y, Varnik A, Wasserman D, Yip P, Hendin H. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294(16):2064–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, Korslund KE, Tutek DA, Reynolds SK, Lindenboim N. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):757–66. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, Xie SX, Hollander JE, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(5):563–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]