1. Introduction

The chemical stability of the central nervous system (CNS) is safeguarded by two major barrier systems that separate the systemic circulation from the cerebral compartment. Within the cerebral compartment, the interstitial fluid (ISF) flows between neurons and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulates among major brain structures and ventricles. The direct continuity of ISF and CSF allows for the free exchange of substances within the extracellular space of the cerebral compartment. Thus, the barrier that separates the systemic compartment from ISF is defined as the blood-brain barrier, while the one that discontinues the circulation between systemic and CSF compartments is named the blood-CSF barrier. The choroid plexus, located within brain ventricles, is the tissue where the blood-CSF barrier is formed (1).

Under the microscope, the choroid plexus consists of three cellular layers: (i) the apical epithelial cells; (ii) the underlying supporting connective tissue; and (iii) the inner layer of endothelial cells. These choroidal epithelial cells have the tight junctions near their apical surface, which seal one to another. The tight junctions constitute a structural basis for the blood-CSF barrier. The barrier impedes the diffusion of water soluble small molecules, proteins, other macromolecules, and ions from the blood to the CSF. The barrier also secretes CSF, which comprises approximately 80–90% of the total CSF. Furthermore, the barrier actively participates in the regulation of the homeostasis of the cerebral compartment. For example, the choroid plexus transports, bidirectionally between blood and CSF, a variety of amino acids (e.g., glycine, L-alanine), hormones (e.g., thyroid hormones, melatonin, growth hormone), peptides (e.g., atriopeptin, vasopressin), proteins (e.g., transthyretin), and drug molecules (e.g., β-lactam antibiotics, cimetidine, benzylpenicillin) (1,2).

Keeping pace with the rapid growth in blood-CSF barrier research, we have developed a primary choroidal epithelial cell culture derived from rat choroid plexus. The plexus tissues are collected from Sprague-Dawley rats, digested, and then mechanically dissociated. The cells are then cultured. Usually the yield is around 2–5 × 105 cells from pooled plexuses of 3 to 4 rats, and they have a viability of 77–85%. Two days after initial seeding, the culture medium is replaced with medium containing cis-hydroxyproline (cis-HP) for 3–5 d to control the growth of fibroblastic cells. The cells are then cultured in the normal medium without cis-HP. The cultures display a dominant polygonal type of epithelial cells, with a population doubling time of 2 to 3 d. Immunocytochemical studies using rabbit anti-rat TTR polyclonal antibody reveal a strong positive stain of transthyretin (TTR), a protein exclusively produced by the choroidal epithelia in the brain. In addition, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) confirms the presence of specific TTR mRNA in the cultures.

We have further adapted this primary culture of choroidal epithelial cells on a freely permeable membrane sandwiched between two culture chambers. The formation of an impermeable confluent monolayer occurs within 5 d after seeding and can be verified by the presence of a steady electrical resistance across the membrane (100–180 ohm × cm2).

This primary cell culture system and the pertinent in vitro model of the blood-CSF barrier have proven useful in studies of thyroxine transport at the blood-CSF barrier and the mechanisms of lead toxicity on CSF transthyretin (3,4,5) (for comments on species other than rat, see Note 1).

2. Materials

2.1. Coating of Culture Dishes

1.0 mg/mL Mouse laminin (Sigma).

Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Life Technologies).

Transwell culture chambers, 12 mm in diameter, 0.4 μm pore size (Corning Costar).

35-mm Tissue culture grade Petri dishes (Falcon).

Coverslips.

0.1% Collagen, type I from rat tail (Sigma), diluted in distilled, deionized water.

2.2. Tissue Separation

Sprague-Dawley rats, both sexes, 4–6 wk old, 80–90 g (Hilltop Inc.).

Pentobarbital.

Dissection kit.

75% Ethanol.

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS): to 800 mL of distilled-deionized water add 8.0 g NaCl, 0.2 g KCl, 1.44 g Na2HPO4, and 0.24 g KH2PO4. Adjust the pH to 7.4 with HCl, and bring the volume up to 1000 mL. Autoclave and store at 4°C.

2.3. Primary Cell Culture

Digestion solution: 4mg/mL pronase (Calbiochem-Novobiochem). Dissolve 6 mg in 1.5 mL HBSS. The solution should then be transferred to a syringe and passed through an attached 0.22-μm low-protein-binding filter unit. The final stock solution (4 mg/mL or 0.4%) should be kept on ice in the culture hood until use. This digestion solution must be made fresh on the day of experiment.

Low-protein-binding filter units (Millex-GV4, 0.22 μm) (Millipore).

0.4% Trypan blue.

cis-HP (CalBiochem-Novabiochem).

0.25% Trypsin, 1 mol/L EDTA (Life Technologies).

2.3.1. Growth Medium

The normal growth medium consists of three major components in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM): (i) antibiotics to prevent infection; (ii) FBS to provide nutrients; and (iii) epidermal growth factor (EGF) to stimulate the growth of epithelia. The growth medium is normally made on the day of use.

DMEM (Life Technologies).

Antibiotic-antimycin (100×) solution (Life Technologies), which contains 10,000 U/mL penicillin, 10,000 μg/mL streptomycin, and 25 μg/mL amphotericin. Keep frozen at −20°C and thaw on the day of use.

FBS (Life Technologies). The solution of FBS arrives in a frozen state. To thaw FBS, the frozen solution should be placed in a refrigerator (4°C) overnight, prior to the experiment. Warm the FBS solution in a 37°C water bath, and then inactivate by incubating at 56°C for 30 min on the day of medium preparation. Inactivated FBS is now commercially available from Life Technologies.

0.1 mg/mL Mouse EGF (Life Technologies). This solution is delivered in a package of 0.1 mg EGF/mL in a vial. Upon arrival, the stock solution should be dispensed into 100-μL aliquots and stored at −20°C until use. The solution is stable for at least 3 mo.

To 450 mL of DMEM, add stock individual solutions in sequence to yield a total volume of 500 mL.

| Volume of Stock Solution | Final Concentration |

| 5 mL of antibiotic-antimycin (100×) | 100 U/mL penicillin 100 μg/mL streptomycin 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin |

| 50 μL of EGF (0.1 mg/mL) | 10 ng/mL EGF |

| 50 mL of inactivated FBS | 10% FBS |

FBS is usually added into the medium immediately before use. The unused medium can be stored at 4°C for the next medium change.

2.3.2. Serum-Free Culture Medium

Some experiments require the use of serum-free culture medium.

Insulin-transferrin-sodium selenite medium supplement (25 mg/mL, 25 mg/mL, 25 μg/mL stock) (Sigma).

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF), from bovine pituitary glands (10 μg/vial) (Sigma).

To prepare total 500 mL medium, the following stock solutions should be added in sequence to 494 mL of DMEM:

| Volume of Stock Solution | Final Concentration |

| 5 mL of antibiotic-antimycin (100×) | 100 U/mL penicillin 100 μg/mL streptomycin 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin |

| 50 μL of EGF (0.1 mg/mL) | 10 ng/mL EGF |

| 1 mL of 2.5 mg/mL insulin, | 5 μg/mL insulin |

| 2.5 mg/mL transferrin, and | 5 μg/mL transferrin |

| 2.5 μg/mL sodium selenite | 5 ng/mL sodium selenite |

| 25 μL of FGF (10 μg/mL) | 5 ng/mL FGF |

Store the serum-free medium at 4°C.

2.4. Two-Chamber Transepithelial Model

Epithelial voltohmmeter (model EVOM) (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL).

2.5. Immunocytochemical Studies

Purified rat plasma TTR and specific rabbit anti-rat TTR polyclonal antibody were the gifts of Dr. W. Blaner at the Institute of Human Nutrition, Columbia University.

4% Paraformaldehyde in PBS.

0.05% Tween-20 in PBS.

1:1250 Rabbit anti-rat TTR antibody, diluted in PBS.

1:200 Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Vector Laboratories), diluted in PBS.

ABC Reagent (Vectastain®) (Vector Laboratories).

Fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Amersham).

Microscope with fluorscein isothiocyanate (FITC) and phase contrast optics.

2.6. RT-PCR

RNAzol B RNA isolation solvent (Tel-Test, Newark, NJ).

RNA PCR core kit, including murine leukemia virus (MuLv) reverse transcriptase Taq DNA polymerase, and random hexamers (Perkin-Elmer).

DNase I (Rnase-free) from bovine pancreas (Sigma).

Isopropanol (Sigma).

Diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) (Sigma).

Chloroform.

Ethanol.

Primers specifically selected for rat TTR (synthesized by Keystone).

RT buffer: 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM each dATP, dTTP, dCTP, and dGTP, and 20 U of RNase inhibitor (GeneAmp).

0.15 μM specific oligonucleotide pairs

PCR buffer: 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, and 2 mM MgCl2.

DEPC-treated Rnase-free solution: 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, and 20 mM NaCl in DEPC-treated water, which is prepared by adding 1 mL of DEPC to 1000 mL of distilled, deionized water, standing overnight, and autoclaving prior to use.

3. Method

3.1. Coating of Culture Dishes

Laminin is the major glycoprotein component of basement membranes and functions to facilitate cell attachment, spreading, and growth (6). Collagen is much less expensive than laminin, but still as effective for cell attachment.

To coat dishes or membranes of Transwell inner chambers with laminin, dilute the stock laminin solution (1 mg/mL) 1:10 with HBSS.

Add an aliquot (100 μL) of diluted laminin solution to 35-mm dishes or Transwell inserts. Swirl the dishes or inserts to ensure an even distribution of the coating solution.

Incubate at room temperature in a culture hood for 10 min.

Remove the excess fluid and allow to air-dry in the hood for at least 1 h prior to cell seeding.

To coat dishes with collagen, dilute collagen with distilled-deionized water to obtain the working concentration of 0.01%.

Apply 0.8 mL of this solution to a 35-mm dish. This is approx 6–10 μg/cm2, since the dish is about 9.6 cm2.

Place the dish in the culture hood at room temperature for 4 to 5 h.

Remove excess fluid and allow the coated dishes air-dry in the hood overnight.

Be careful to avoid contamination during the coating process.

3.2. Tissue Separation

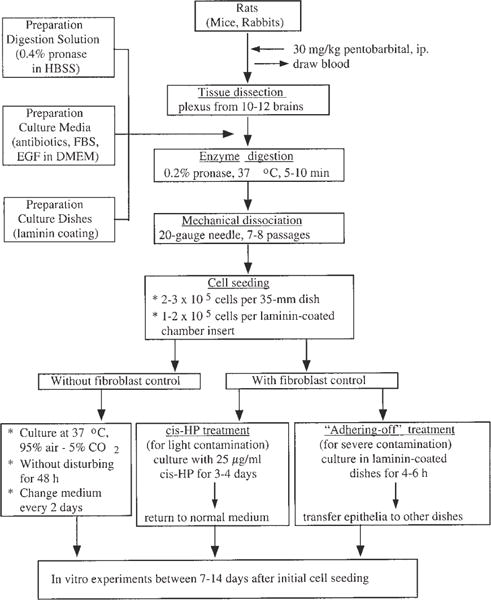

Fig. 1 illustrates the flowchart of the procedures pertaining to primary culture of choroidal epithelial cells.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the procedures in establishing primary culture of choroidal epithelial cells.

Anesthetize the rats with an i.p. injection of 30 mg/kg pentobarbital.

To minimize the amount of blood present in choroid plexus tissues, draw as much blood as possible from the inferior vena cava using a syringe.

Remove the hair on the back of the head with a pair of scissors.

Sterilize the exposed skin using cotton wool saturated with 75% ethanol.

Remove the brain from the skull and place in a beaker containing PBS on ice, to chill the tissues, and wash off excess blood.

When you have a pool of 5–8 brains, place into the culture hood for dissection of the choroid plexus.

Dissect the choroid plexuses from both the lateral and third ventricles and immerse in 2 mL of HBSS.

After tissues have been collected from 10–15 brains, rinse the pool of choroid plexuses in HBSS, and transfer to another beaker containing 0.5 mL of HBSS.

Mince the plexus tissues with fine ophthalmologic scissors, so that they are about 1-mm cubes.

Bring the total volume up to 1 mL.

3.3. Primary Cell Culture

3.3.1. Tissue Digestion

Add 1 mL of digestion solution to the beaker, to give a final pronase concentration of 0.2%.

Shake the beaker lightly by hand to allow a complete mixing of the digestion solution with tissues.

Incubate at 37°C for 5–10 min.

Stop the digestion reaction by adding 4 mL of HBSS solution to the digestion mixture (see Note 2).

Centrifuge at 800g for 5 min, and then decant the supernatant, which contains primarily nonepithelial cells.

Wash the pellet, which consists of cell clumps of primary epithelial cells (probably joined by tight junctions), in 4 mL of HBSS.

Resuspend in 4 mL of growth medium.

Mechanically dissociate the cells by 7 to 8 forced passages through a 20-gauge needle (see Note 2).

Remove an aliquot (0.1 mL) of cell suspension and mix with 0.1 mL of 0.4% Trypan blue to count cell numbers and to assess the viability.

The procedure for cell isolation described here yields around 0.8–1 × 105 epithelial cells per rat.

3.3.2. Culture of Epithelial Cells

Prior to cell seeding, dilute the cell preparations with growth medium to approx 1–2 × 105 cells/mL (see Note 3).

Plate the cells onto 35-mm coated Petri dishes (2 to 3 × 105 cells per dish) and culture in a humidified incubator with 95% air/5% CO2 at 37°C.

Leave the cultures undisturbed for at least 48 h following initial seeding, to ensure a good cell attachment.

Change the medium every 2 d thereafter for the duration of the culture.

Two days after initial seeding, remove the culture medium, and replace with fresh medium containing 25 μg/mL of cis-HP to control fibroblast contamination (see Note 4).

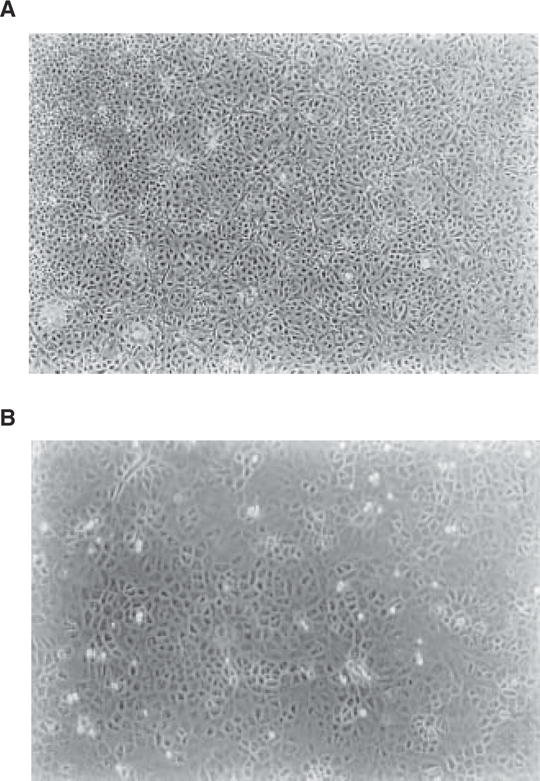

Usually the treatment with cis-HP suffices for the purpose of inhibition of the growth of fibroblasts. Typical microphotographs of cultured choroidal epithelia under phase contrast microscope are presented in Fig. 2.

After 3–5 d culture with cis-HP, return the cells to normal growth medium without cis-HP, providing that there are no visible fibroblasts under the microscope.

From our own experience, if the digestion procedure works well, the epithelia usually attaches and grows rapidly. Therefore, the treatment with cis-HP may not be necessary.

If the choroid plexus tissues are harvested from older animals, e.g., >4–6 mo old, the contamination of the culture with fibroblasts can sometimes become a serious problem. A method of “fibroblast adhering-off” should be used to deal with this problem.

Initially, seed the cell preparation onto laminin-coated dishes.

Six hours after seeding, transfer the culture medium containing the majority of unattached epithelial cells to another dish, to continue epithelial culture.

This treatment effectively leaves fibroblasts behind in the laminin-coated dishes, because fibroblasts usually attach to the laminin-coated surface much faster (4- to 6-h incubation) than the epithelial cells (16–24 h).

To detach the cells for bioassays, incubate the culture with trypsin-EDTA in PBS at 37°C for 10 min.

Harvest the cells, centrifuge, and wash. They can then be used for further studies.

Fig. 2.

Primary culture of choroidal epithelial cells after 7 d in culture: (A) ×40, (B) ×100. Note the confluent layer of the cells with predominant polygonal cell type. The choroid plexuses were obtained from 5-wk-old Sprague-Dawley rats.

3.4. Two-Chamber Transepithelial Model

The procedure for preparation of epithelial suspension is the same as described in Subheading 3.3.

Prior to seeding the cells in Transwell inner chambers (inserts), coat the permeable membranes attached to the inserts with laminin as described in Subheading 3.1. (see Note 5).

Plate aliquots (0.5 mL) of cell suspension onto 12-mm laminin-coated culture wells (2 × 105 cells/well).

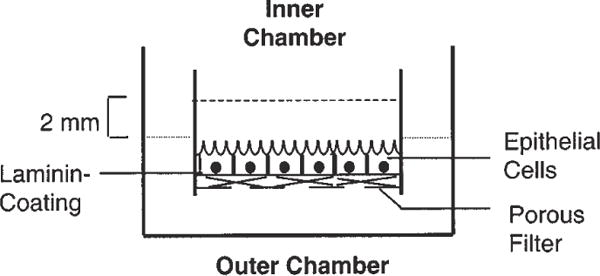

Insert the inner chambers into the outer (basal) chambers, which should already contain 1 mL of growth medium (Fig. 3).

Allow cells to grow for 48 h.

Change the medium every 2 d thereafter.

The formation of confluent impermeable cell monolayers is judged by two criteria: (i) the height of the culture medium in the inner chamber has to be at least 2 mm higher than that in the outer chamber for at least 24 h; and (ii) the electrical resistance across the cell layer has to fall into the range of 100–180 ohm × cm2.

Transepithelial electrical resistance can be measured using an epithelial voltohmmeter after cells have been cultured in the chambers for at least 4 d.

The net value of electrical resistance is calculated by subtracting the background (which is measured on laminin-coated cell-free chambers) from values of epithelial cell-seeded chambers.

Fig. 3.

Transepithelial model of blood-CSF barrier used to study transepithelial transport. Epithelial cells are connected by tight junctions and form a barrier between fluids in the inner and outer chambers. Fluid in the inner chamber is in contact with the apical surface of the cells, while the fluid in the outer chamber has access to the basal surface of the cells.

3.5. Immunocytochemical Studies

A reliable method for identification of choroidal epithelial cells is visualization of TTR (see Note 6), a unique marker for choroidal epithelial cells. TTR is a 55,000-Da protein consisting of 4 identical subunits in tetrahedral symmetry. Per unit of weight, rat choroid plexus contains 10 times more TTR mRNA than liver, and per gram of tissue, synthesizes TTR 13 times faster than the liver, which is the major organ producing serum TTR (7,8).

Culture cells that are to be stained on a laminin-coated glass coverslip for 5–7 d.

Fix the cells in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS.

Wash 3 times with PBS.

Permeabilize cell monolayers by washing with 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS 3 times.

Incubate the cells with rabbit anti-rat TTR antiserum at room temperature for 30 min.

Rinse with 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS one more time to reduce the background.

Incubate the cultures for 30 min with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody.

Stain the cultures with ABC reagent (Vectastain®) to form avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase complex.

For immunofluorescent staining, treat the cells in the same way as described above, except that the secondary antibody should be fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody.

Examine the cells under FITC fluorescence and phase contrast optics (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Cultured choroidal epithelial cells possess cytosolic TTR by immunofluorescent staining. Cells were treated with anti-TTR primary antibody followed by secondary antibody conjugated with fluorescein. Note the positive staining in cytosol (×300).

3.6. RT-PCR Analysis

While immunohistochemical staining of TTR proteins is regarded as the best approach to identify choroidal epithelial cells, there is no anti-rat TTR antibody commercially available in the current market. Thus, one may use an alternative approach to examine the mRNA encoding TTR by using a reverse PCR technique.

Extract total RNA from the cultured cells or rat liver (as a positive control) according to the procedure described by Sambrook et al. (9) or using an RNA isolation kit (RNAzol B).

Homogenize cells or tissues in RNAzol B solution, followed by a chloroform extraction to remove DNA and proteins.

Precipitate RNA in isopropanol and wash with 75% ethanol.

Resuspend in DEPC-treated RNase-free solution.

Prior to transcription, digest RNA extracts with DNase to eliminate contaminated DNA.

Carry out the RT on 1 μg of total RNA, using MuLv reverse transcriptase with random hexamers (2.5 μmol/L) or selected antisense primer (0.75 μmol/L) in 20 μL RT buffer.

Carry out the reaction at 42°C for 45 min.

For PCR amplification, one set of specific oligonucleotide pairs should be incubated with the above reaction mixture.

Add 80 μL PCR buffer, containing 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase, giving rise the total volume of 100 μL.

The cycle parameters are: 5 min at 94°C for initial denaturation, 1 min at 55°C for annealing, and 0.5 min at 72°C for extension. The subsequent cycle: 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 0.5 min at 72°C for 35 cycles. Follow this with a final 5-min incubation at 72°C.

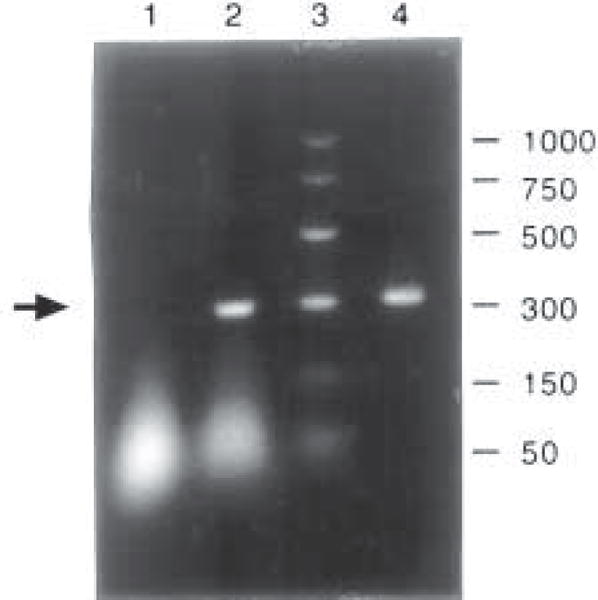

An aliquot (10 μL) of each reaction mixture should be analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels containing 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide (Fig. 5).

- The primers (custom-synthesized) designed by us specifically for rat TTR consist of:

Primer sense: 5′-CCTGGGGGTGCTGGAGAAT-3′ Primer anti-sense: 5′-ATGGTGTAGTGGCGATGAC-3′

Fig. 5.

Cultured choroidal epithelial cells express TTR mRNA by RT-PCR analysis. All samples underwent DNase digestion and RT-PCR unless otherwise stated. Arrow indicates bands corresponding to TTR mRNA. Lane ID: 1, cultured plexus cells, total RNA for PCR without RT; lane 2, cultured plexus cells, mRNA with selected primer; lane 3, base pair markers; and lane 4, liver, mRNA with selected primer.

This amplifies a product of 317 bp covering most of the TTR mature peptide region from rats (7).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the gift of rat TTR antibody from Dr. William S. Blaner in the Institute of Human Nutrition, Columbia University. This research was supported in part by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant Nos. RO1 ES-07042 and RO1 ES-08146.

Footnotes

Adaptability of the current protocol to plexus tissues obtained from other species. We have tried to adapt this protocol to establish the primary culture of choroidal epithelial cells derived from mice, rabbits, and dogs. The morphology, as well as the growth property, of cells from mice and rabbits shared many similarities with those from rats; however, cultures from dogs were problematic. Canine plexus cells appear to be very sensitive to pronase treatment, as few attached epithelial clusters could be seen after digestion. From the economic point of view, culturing one dish of rat plexus cells (usually requiring three rats) costs the dollar equivalent to that of rabbit (one per dish). Thus, the option as to which species is chosen is solely dependent upon the purpose of the study.

Isolation of epithelial cells from the choroid plexus. To ensure a high yield of epithelial cells, the digestion procedure is critical. We have tried collagenase (2 mg/mL) and pronase (2 mg/mL) to digest tissues, and found that collagenase treatment results in low cell viability and poor cell attachment. Digestion with pronase, on the other hand, effectively releases epithelial cells. However, the duration and the concentration of pronase must be well controlled. The time for an ideal digestion varies depending upon the tissue mass. The rule of the thumb is to watch carefully the color change of the culture medium. With a complete digestion, the medium usually turns from light red to yellowish orange and from relatively transparent to cloudy. A thin layer of cell clumps will visibly smear the bottom of the beaker. Digestion with pronase should not last for over 10 min, since prolonged digestion reduces cell attachment in the later stage. It should also be noted that the activity of pronase often varies among different batches of shipment. Thus, an ideal digestion condition needs to be tested out for each shipment. The other seemingly trivial, yet absolutely important procedure, is the mechanical dissociation of the cells. The epithelial clumps after enzyme digestion normally attach to the surface of the dish; but tend to form less colonies if they are not further disintegrated. Forcing the cell preparation to pass through the needle effectively triturates the cell clumps and produces the maximal yield of epithelia, thus increasing the cell colonies and plate efficiency.

Density of cells for initial seeding. The healthy growth of choroidal epithelia requires a sufficient number of cells at the stage of cell seeding. When the cells are initially plated at total numbers that are less than 104/mL, the cell proliferation can become very slow. We recommend seeding the cells at a density of 2 to 3 × 105 cells/35-mm dish, which is about 2 mL of 1 to 2 × 105 cells/mL after digestion. The other technical detail worthy of mention pertains to the transfer of the cells from centrifuge tubes to culture dishes. The tips of glass pipets must be moistened with culture medium prior to the transfer of cells. This procedure minimizes the loss of dissociated cells, which are prone to sticking to the dry tip of a glass pipet.

Control of fibroblasts. One clear challenge for successful culture of choroidal epithelial cells is the control of contamination by fibroblasts. Under the light microscope, fibroblasts are typically elongated in the direction of cell stretch, and their nuclei are condensed. Fibroblasts usually spread in the space between epithelial clusters. We have tried several methods to block fibroblast growth. Initially, we attempted to exclude or reduce serum, which contains FGF, from the culture medium. By reducing the FBS to 5% of the culture medium, however, the overall growth of the culture was significantly weakened as evidenced by slow growth of epithelial cells and decreased viable cell numbers. We then experimented with a specific fibroblast inhibitor cis-HP (10,11). The presence of cis-HP did inhibit the growth of fibroblasts, but it also affected the normal growth of epithelia. Our experience suggests that both the concentration of cis-HP and the time of its addition to the medium are critical. Higher concentration and earlier treatment, while most effectively inhibiting fibroblastic contamination, killed the epithelia as well. We found that the optimal condition for cis-HP treatment is to add 25 μM cis-HP to the culture medium at 48 h after initial seeding. This procedure achieves a good result with the plexus culture derived from young animals, since the young plexus tissues contain fewer fibroblasts, and their epithelia tend to tolerate cis-HP treatment. During the second week of culture, cis-HP can be withdrawn from the medium, if fibroblastic cells do not become visible under phase contrast microscope. For the choroid plexus obtained from the older animals (4–6 mo old) or from other larger species such as dog, the fibroblast adhering-off approach proves practical in eliminating fibroblasts. This approach takes advantage of a higher affinity of fibroblasts than epithelia to collagen or laminin-coated surfaces in the early cell selection stage. A relatively complete fibroblast adhering would occur 12 h after incubation of digested cells in coated dishes. However, appreciable numbers of epithelial clusters could also attach to the coated wall during this period and, therefore, suffer loss in subsequent cell transfer procedure. Thus, the adhering treatment for 4–6 h is a reasonable approach.

Culture on Transwells. The procedure for culture of choroidal epithelia on Transwell membrane is the same as that used in the routine cultures, except that the cells must be seeded on a laminin-coated membrane. Cells grown on the membrane of the inner chambers display similar morphology to those observed in the culture dishes and survived for at least 2 wk. Since the epithelial cells are connected by tight junctions when they grow to a confluent monolayer, the cells actually form an impermeable barrier between the media in the inner and outer chambers. The net electrical resistance across this barrier in our study (100–180 ohm × cm2) is comparable to those reported by others, e.g., 99 ± 15 ohm · cm2 (3) and 170 ohm × cm2 (12). It is worth noting that many factors can interfere with the determination of electrical resistance, such as the difference in preparations (tissue vs cultured cells), temperature, pH (physiological solutions vs culture media), age of tissues or cultures, and the freshness of culture medium. In our own experiments, a higher pH, colder culture medium, or fresher preparation usually resulted in a higher resistance reading. We have used an 8-d culture to study thyroxine transport in this in vitro model of blood-CSF barrier and demonstrate that lead (Pb) exposure hinders the transepithelial transport of thyroxine (4,5). This appears to be due to the inhibitory effect of Pb on the production and secretion of TTR by the choroid plexus (13,14). Recently, we have also applied this model to study iron transport at the blood-CSF barrier (data not shown). From these studies, we observe that transepithelial transport of metal ions appears to be a rather slow process; sometimes it takes more than 24 h to reach equilibrium. A short time course of the study would probably fail to reveal the steady state transport of substances across the blood-CSF barrier. Thus, caution must be taken to allow for sufficient time for the substances to reach steady-state equilibrium.

Characterization of choroidal epithelial cells. Immunohistochemical staining with anti-TTR antibody is the most reliable method to distinguish choroidal epithelia from the cells of other origins, since TTR has been repeatedly demonstrated to present exclusively in the choroidal epithelia in the brain (15,16). Because of the lack of commercial TTR antibody, the reverse PCR to examine TTR mRNA seems to be an indispensable checkmark for the choroidal epithelia. The sequence of TTR mRNA was originally reported by Dickson et al. (7). We have designed the primer set for the purpose of RT-PCR of TTR mRNA from rat. The method presented in this article exhibits a good consistency in our cultured cells, freshly isolated choroid plexus tissues, and liver cytosolic preparations. In summary, the establishment of choroidal epithelial cell culture has been described in the literature for cells from various sources, including mouse (17,18), rat (18–20), rabbit (6), sheep (21), and cow (10,22). Some have the advantages over others. We describe here a simple and reproducible method to culture epithelial cells derived from rat, mouse, and rabbit. The cultures possess relatively uniform epithelial cell type with minor contamination from fibroblasts. The epithelial cells grown on a Transwell device form a confluent epithelial barrier between two compartments. This in vitro culture system is useful in studying physiology, biochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology of blood-CSF barrier.

References

- 1.Zheng W. Toxicology of choroid plexus: special reference to metal-induced neurotoxicities. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;52:89–103. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20010101)52:1<89::AID-JEMT11>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng W. The choroid plexus and metal toxicities. In: Chang LW, Magos L, Suzuki T, editors. Toxicology of metals. CRC Press; New York: 1996. pp. 609–626. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Southwell BR, Duan W, Alcorn D, Brack C, Richardson S, Kohrle J, Schreiber G. Thyroxine transport to the brain: role of protein synthesis by the choroid plexus. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2116–2126. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.5.8404661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng W, Zhao Q, Graziano JH. Primary culture of rat choroidal epithelial cells: a model for in vitro study of the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier. In Vitro Cell Biol Dev. 1998;34:40–45. doi: 10.1007/s11626-998-0051-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng W, Blaner WS, Zhao Q. Inhibition by Pb of production and secretion of transthyretin in the choroid plexus: its relationship to thyroxine transport at the blood-CSF barrier. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;155:24–31. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer SE, Sanders-Bush E. Sodium-dependent antiporters in choroid plexus epithelial cultures from rabbit. J Neurochem. 1993;60:1304–1316. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickson PW, Howlett GJ, Schreiber G. Rat transthyretin (prealbumin): molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence, and gene expression in liver and brain. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:8214–8219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schreiber G, Aldred AR, Jaworowski A, Nilsson C, Achen MG, Segal MB. Thyroxine transport from blood to brain via transthyretin synthesis in choroid plexus. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:R338–R345. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.2.R338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T, editors. Molecular cloning. CSH Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. pp. 7.6–7.11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crook RB, Kasagami H, Prusiner SB. Culture and characterization of epithelial cells from bovine choroid plexus. J Neurochem. 1981;37:845–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1981.tb04470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kao W, Prokop D. Proline analogue removes fibroblasts from cultured mixed cell population. Science. 1977;266:63–64. doi: 10.1038/266063a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saito Y, Wright EM. Bicarbonate transport across the frog choroid plexus and its control by cyclic nucleotides. J Physiol. 1983;336:635–648. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng W, Perry DF, Nelson DL, Aposhian HV. Protection of cerebrospinal fluid against toxic metals by the choroid plexus. FASEB J. 1991;5:2188–2193. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.8.1850706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng W, Shen H, Blaner SB, Zhao Q, Ren X, Graziano JH. Chronic lead exposure alters transthyretin concentration in rat cerebrospinal fluid: the role of the choroid plexus. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1996;139:445–450. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aldred AR, Brack CM, Schreiber G. The cerebral expression of plasma protein genes in different species. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1995;111B:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(94)00229-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herbert J, Wilcox JN, Pham KC, et al. Transthyretin: a choroid plexus-specific transport protein in human brain. Neurology. 1986;36:900–911. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.7.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouille C, Mesnil M, Barriere H, Gabrion J. Gap junctional intercellular communication between cultured ependymal cells, revealed by Lucifer yellow CH transfer and freeze-fracture. Glia. 1991;4:25–36. doi: 10.1002/glia.440040104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peraldi-Roux S, Nguyen-Than Dao B, Hirn M, Gabrion J. Choroidal ependymocytes in culture: expression of markers of polarity and function. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1990;8:575–588. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(90)90050-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strazielle N, Ghersi-Egea JF. Demonstration of a coupled metabolism-efflux process at the choroid plexus as a mechanism of brain protection toward xenobiotics. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6275–6289. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06275.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsutsumi M, Skinner MK, Sanders-Bush E. Transferrin gene expression and synthesis by cultured choroid plexus epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:9626–9631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harter DH, Hsu KC, Rose HM. Immunofluorescence and cytochemical studies of visna virus in cell culture. J Virol. 1967;1:1265–1270. doi: 10.1128/jvi.1.6.1265-1270.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whittico MT, Hui AC, Giacomini KM. Preparation of brush border membrane vesicles from bovine choroid plexus. J Pharmacol Methods. 1991;25:215–227. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(91)90012-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]