Abstract

The genus Yersinia includes species with a wide range of eukaryotic hosts (from fish, insects, and plants to mammals and humans). One of the major outer membrane proteins, the porin OmpC, is preferentially expressed in the host gut, where osmotic pressure, temperature, and the concentrations of nutrients and toxic products are relatively high. We consider here the molecular evolution and phylogeny of Yersinia ompC. The maximum likelihood gene tree reflects the macroevolution processes occurring within the genus Yersinia. Positive selection and horizontal gene transfer are the key factors of ompC diversification, and intraspecies recombination was revealed in two Yersinia species. The impact of recombination on ompC evolution was different from that of another major porin gene, ompF, possibly due to the emergence of additional functions and conservation of the basic transport function. The predicted antigenic determinants of OmpC were located in rapidly evolving regions, which may indicate the evolutionary mechanisms of Yersinia adaptation to the host immune system.

Keywords: porins, Yersinia, pathogen adaptation, recombination, outer membrane

Introduction

The genus Yersinia belongs to the family Enterobacteriaceae and includes 17 species. The three species that are pathogenic to humans (Yersinia pestis, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, and Yersinia enterocolitica) are very well studied; the other 14 species are considered nonpathogenic to humans but can cause infections in fish (Yersinia ruckeri), insects (recently described Yersinia entomophaga), and mammals (Yersinia intermedia, Yersinia frederiksenii, and Yersinia kristensenii).1,2 Pathogenic Yersinia species cause zoonoses that circulate in a natural focus, with humans as an accidental host. In that case, man provides a new, unusual ecological niche for the pathogens.3 Survival of bacteria in the new environment will depend on the presence of adaptation factors that appeared in the previous habitat as random events of evolution. In this context, Yersinia is a model genus for the study of evolutionary events that contribute to the emergence and development of pathogenic potential.1,4

Nonspecific general porins are β-barrel proteins and predominant among the outer membrane proteins (OMPs) of gram-negative bacteria. Porins provide passive transport of small molecules through the outer membrane and modulate the membrane’s permeability to harmful molecules, such as bile salts, antibiotics, and biocides. Furthermore, some porins could induce bacterial invasion and create protective immunity against bacterial infections.5–8 The reciprocal expression of two general porins, OmpC and OmpF, is one of the common ways that bacterial cells adapt to changing environmental conditions.9–11 For example, OmpF (which has a large pore size) is mainly expressed at a temperature of 4 °C–25 °C and when there is a lack of nutrients in the medium, while OmpC (which has a smaller pore size) is primarily expressed at the temperature of a warm-blooded organism (37 °C) and during nutrient excess,12 OmpC plays a more significant role in bile resistance than OmpF.13 Therefore, these proteins may contribute to the adaptation of bacterial pathogens to different hosts and different environmental conditions.

Previously, we found that the ompF gene of Yersinia is characterized by pronounced interspecific and intraspecific polymorphisms. The interspecies and intraspecies recombination and positive selection within the gene play important roles in its diversification. Our analysis demonstrated that ompF evolved with a nonrandom mutation rate under overall purifying selection; however, the regions encoding the surface loops of OmpF contain sites subjected to positive selection.14,15 Therefore, the study of evolution of OmpC, the second main porin of Yersinia, which is predominantly expressed in warm-blooded organisms, will allow us to advance our understanding of the mechanisms of pathogen adaptation and survival in the host environment.

In this study, we defined the mechanisms of molecular evolution of OmpC based on an investigation of gene sequence divergence among all currently known Yersinia species.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and data collection

A total of 90 nucleotide coding sequences that represent 15 different species of Yersinia and Serratia marcescens as the out-group were used in this study. These sequences were obtained from the DNAs of the 39 previously described strains14 and from the genomes of 51 strains retrieved from the GenBank and SRA databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). All row data were assembled in the CLC Genomics Workbench (Qiagen), followed by annotation on the RAST server.16 Some properties of these strains and the ID numbers of the genomes and sequences are presented in Supplementary Table 1. We identified OmpC orthologs in the genomes by examining the neighbor genes on both sides of the ompC gene. The flanking genes were a penicillin-binding protein, ampH (COG1680), a small regulatory RNA gene, micF, and an Major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporter, HlyD (COG0845).17 Strain selection was intended to include the strains of all known Yersinia species with a high degree of diversity (Supplementary Table 1).

PCR and sequencing

PCR amplification of the ompC gene was performed with the universal primers YeC-seq1 5′-CCATTGGGATTATATGCTCG-3′ and ompC-Rent 5′-CYTRTWATCAGRATTAGAACTGG-3′, designed in this study using Vector NTI Advance v. 11.0 (Invitrogen Corp.). The expected amplicon sizes were 1100–1152 bp. The PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 minutes, then 25 cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, 55 °C for 30 seconds, and 72 °C for 45 seconds, followed by a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 minutes. The PCR fragments were evaluated on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Unincorporated primers and Deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) were removed from PCR products with a GeneJET PCR Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific). The purified PCR fragments were sequenced on a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Phylogenetic analyses

The primary screening of the obtained nucleotide sequences was performed using Sequence Scanner v. 1.0 (Applied Biosystems). A multiple alignment was performed using ClustalW implemented in MEGA v. 6.06.18 Phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA v. 6.06. All three coding positions were examined and the neighbor-joining and maximum likelihood methods with the Kimura 2-parameter model were applied. The reliability of the phylogenetic trees was checked with a bootstrap test (2000 replications).

Evolution analysis

We used the server Datamonkey (www.datamonkey.org)19 and the RDP4 program,20 for recombination detection. In Datamonkey, the calculations were performed using the GARD method.21 In the RDP4, recombinant sequences were detected via four automated recombination detection methods: RDP,22 MaxChi,23 Chimera,24 and GENECONV.25 For the RDP method, internal reference sequences were used, the window size was set to 20, and the sequence identity of 0%–100% was used. For both the MaxChi and the Chimera methods, the number of variable sites was set to 40. For the GENCONV method, we used standard settings. A maximum P-value of 0.01 and the Bonferroni correction were used.

Positive or negative selection was calculated as the proportion of synonymous (silent; dS) to nonsynonymous (amino acid changing; dN) substitution rates. The analysis was performed on the Datamonkey web server using SLAC, FEL, REL,26 and IFEL27; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for these tests.

Nucleotide divergence (Pi) – the number of nucleotide differences in the site28 – was determined using DnaSP v. 5.10,29 using the sliding window with a length of 5 and a step size of 1.

The prediction of B-cell epitopes in the protein- coding sequences was carried out on the IEDB Analysis Resource server (http://tools.immuneepitope.org) using the BepiPred method.30

Results and Discussion

Phylogenetic and recombination analyses of ompC

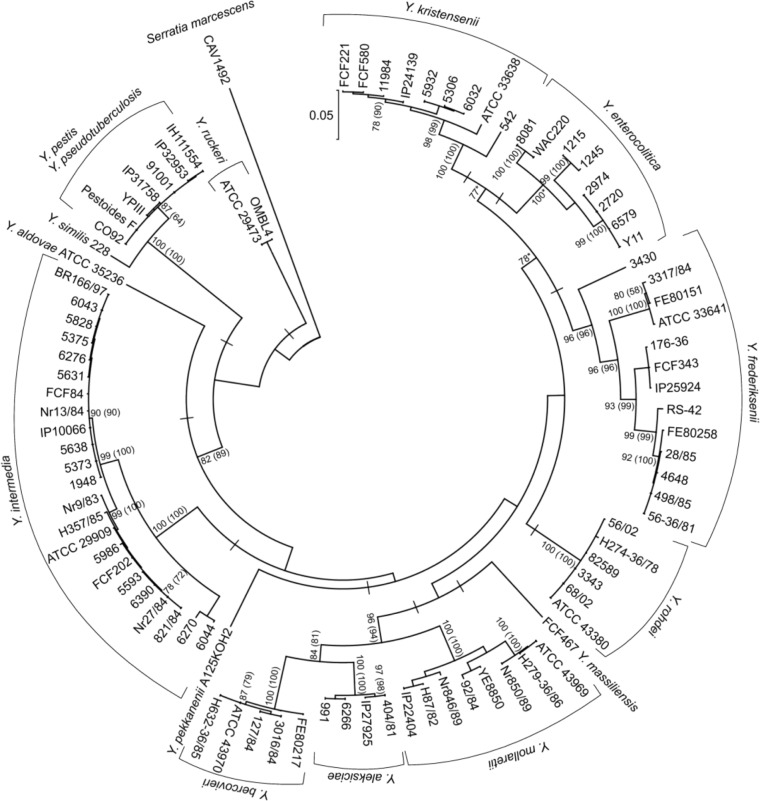

We used the previously obtained DNA of 39 Yersinia strains14 for the sequencing of the full-length coding sequences of ompC; these sequences were combined with the sequences from the GenBank and SRA databases. Overall, we analyzed 90 sequences that represented 15 species of Yersinia and S. marcescens as the out-group (Supplementary Table 1). All sequences were aligned and analyzed in MEGA. Figure 1 shows a maximum likelihood tree of ompC. For the neighbor-joining method, we obtained lower bootstrap values (shown in parentheses in Fig. 1). The tree was formed by 11 ancient clades (indicated as short perpendicular lines in Fig. 1), but the degree of evolutionary relatedness between them was impossible to identify because of the low bootstrap values. In general, the ompC tree topology reflects the macroevolution processes occurring within the genus Yersinia; all the species form distinct monophyletic groups within the ancient clades, excepting Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis, which merge in one Y. pseudotuberculosis complex. The tree topology correlates well with previously constructed phylogenetic trees for the genus Yersinia.4,31

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood tree of Yersinia ompC. The scale displays the number of nucleotide substitutions per nucleotide site. Numbers at nodes of the tree – the bootstrap value in percentage (75% cutoff). Bootstrap values obtained for the neighbor-joining method are in parentheses.

Note: *Difference in the tree topology when compared with the neighbor-joining one. S. marcescens CAV1492 – out-group.

From our data and data in the literature, porin genes often contain signatures of past intra- and intergenic recombination.14,32,33 To understand the role of horizontal gene transfer in ompC evolution, we analyzed the sequences for the presence of recombination using the GARD method on the Datamonkey server. When we analyzed all the unique sequences (n = 77), the method did not reveal any recombination events. Then, we decided to divide these sequences into seven clusters, based on the phylogeny and genetic distance between the most divergent species. Five clusters presented distinct species (Y. frederiksenii, Y. intermedia, Y. enterocolitica, Yersinia rohdei, and Y. kristensenii). Two clusters combined several closely related species: the YPS cluster, which included Y. pseudotuberculosis, Y. pestis, and Yersinia similis, and the YM cluster, which included Yersinia mollaretii, Yersinia bercovieri, and Yersinia aleksiciae. As a consequence of this division, we could detect recombination in the four clusters (Table 1). We also used the RDP4 program to identify parental sequences and determine their contribution to a mosaic structure of ompC. We revealed two recombination events in the Y. frederiksenii cluster and one in the Y. enterocolitica cluster. Thus, we found evidence for intraspecies recombination in at least two species.

Table 1.

Results of recombination detecting.

| CLUSTER | GARD | RDP4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RB* NUMBER | RB LOCATION IN ALIGNMENT, BP | P-VALUE | RE** NUMBER | RE LOCATION IN ALIGNMENT, BP | |

| Y. frederiksenii | 1 | 480 | 0.05 | 2 | 308–393, 661–865 |

| Y. enterocolitica | 1 | 1053 | 0.01 | 1 | 626–914 |

| Y. kristensenii | 2 | 162,924 | 0.01 | ||

| YM | 1 | 859 | 0.01 | ||

Notes:

Recombination break point.

Recombination event.

Apparently, recombination in ompC occurs only between closely related strains. Despite the same levels of polymorphism in the two main porin genes, ompC was not involved in horizontal gene transfer between species of Yersinia, whereas both intra- and interspecific recombination were found in ompF.14,15

Thus, we can suppose that the ompC gene of Yersinia has evolutionary constraints on recombination between different species. Homologous recombination is common for many bacterial porin genes and is one of the mechanisms of their diversification34,35; however, the comparison of the two main nonspecific porins (OmpC and OmpF) of Yersinia revealed very different contributions of recombination to their evolution that could be due to the emergence of additional functions, while the basic transport function remained intact for both proteins.

Evolutional analysis

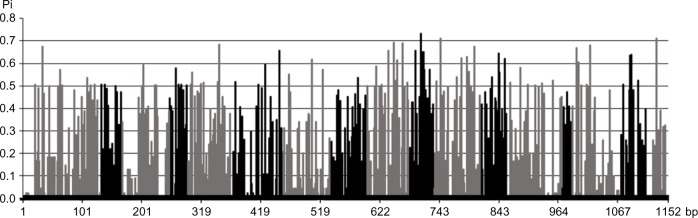

The ompC genes of Yersinia are orthologous, and their evolution are determined by microevolution processes, like mutations and selection through speciation. The evolutionary divergence of the analyzed ompC sequences was 0.145 ± 0.006. We detected 475 variable nucleotide sites, which comprised 41% (475/1152 bp) of the length of a multiple alignment that included unique sequences (n = 77). The domain organization of Yersinia OmpC was determined based on the structural data of Escherichia coli OmpC (Osmoporin, 2 J1 N, RCSB PDB). It was unexpected that the distribution of variable sites was uniform throughout the ompC length, regardless of the protein structure (Fig. 2). We previously showed that the ompF gene of Yersinia is characterized by an uneven distribution of variable sites, which are preferentially localized in the regions encoding the external loops.14 The nonrandom distribution with variable and conserved domains is common for the porin genes of different bacteria.35,36

Figure 2.

Nucleotide divergence (Pi) of ompC. Regions encoding the periplasmic loops and transmembrane strands are indicated by gray shading, the regions encoding the external loops (L1–L8) are colored by black shading.

We consider that the difference in the evolutionary rates of different parts of orthologs is associated with evolutionary pressure acting as a purifying or positive selection. As Zheng et al.37 showed, rapidly evolving gene regions may result in the functional divergence of proteins, significantly contributing to the phenotypic differences between closely related organisms.

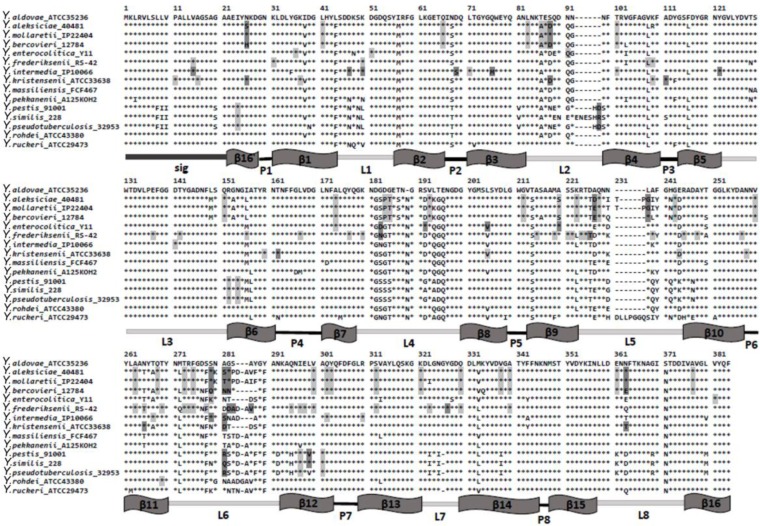

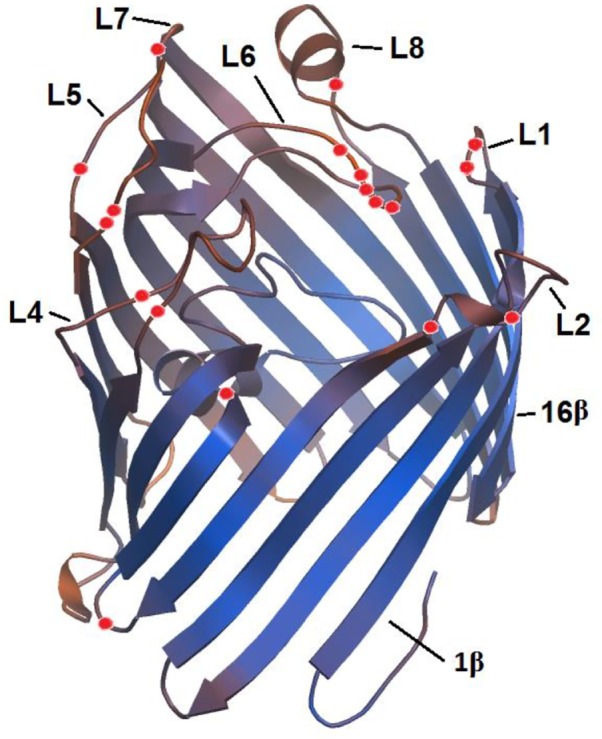

We tested the effects of adaptive evolution on the ompC gene of Yersinia. The analysis was performed on the Datamonkey server, using SLAC, FEL, IFEL, and REL. We detected the sites under positive and negative selection in seven previously identified clusters. The positive codons were found in the six clusters excepting the Y. rohdei cluster (Fig. 3); positive sites were preferentially located within regions encoding the external loops of the protein. For example, in the YM cluster, seven out of eight positive codons were focused in the coding regions corresponding to the L2, L5, L6, and L8 loops. In the Y. enterocolitica group, we found four sites, and two of them were in the L4 loop region. In the Y. frederiksenii cluster, we identified six codons located in the L4, L5, L6, and L7 regions (Fig. 3). These sites were mapped onto three-dimensional structural model of OmpC, which is presented in Figure 4. The positive sites were in different loops of different Yersinia species and may be the evidence of the functional divergence of these loops in speciation. The negative codons found in all seven clusters encoded amino acid residues that maintain the β-barrel structure (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Multiple alignment of OmpC sequences from Yersinia species.

Notes: β1–β16 – transmembrane β-strands; β16 – part of β16-strand; L1–L8 – external loops; P1–P8 – periplasmic loops. Amino acid residues that demonstrated negative selection are marked by light gray shading; amino acid residues that demonstrated positive selection are marked by dark gray shading.

Figure 4.

Location of positively selected sites in simulated structure OmpC porin of Y. pseudotuberculosis.

Note: Sites that show positive selection are marked by red spheres.

We have previously shown that intensive diversification of the ompF gene of Yersinia occurred in different external loops of different species14; the same feature was described in several studies of other bacterial porins.38,39 Apparently, the presence of both negative and positive selection is the common characteristic of bacterial porins. Thus, the ompC gene of Yersinia evolves with a conserved protein structure, which is essential for the basic transport function, and diversification of the external loops, which allow the protein to develop additional functions.

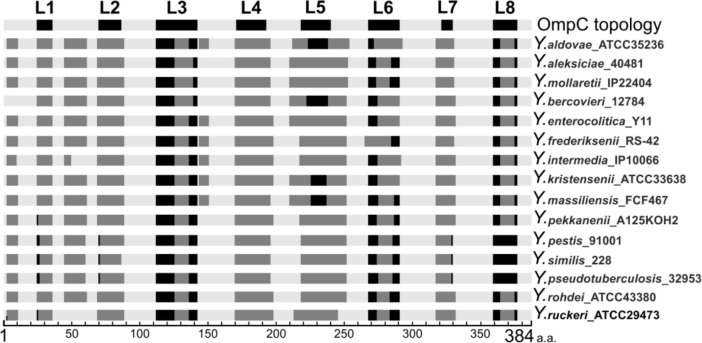

Antigenic determinant analysis

Porins are well known as antigenic and immunogenic proteins.7,8 Their rapidly evolving regions that generally correspond to the external loops can serve as a molecular basis for the emergence of antigenic variation and escaping from the host immune system.40 We analyzed OmpC sequences from each species on the IEDB Analyses Resource server to predict linear B-cell epitopes in a protein. Figure 5 schematically represents the predicted antigenic determinants along the peptide chain. The number and localization of epitopes were almost the same among the different species, whereas their sequence heterogeneity was remarkably different. We suggest that this high sequence variability may result in the immunological heterogeneity of OmpC in different Yersinia species. Differential levels of cross-reactivity between the different porin variants were previously reported.35,41 In the experiments, the authors demonstrated that antibodies prepared against one porin variant either weakly bind or do not interact with other variants, confirming that the variable external loops contain regions suitable for the development of OmpC-based vaccines and diagnostic assays.

Figure 5.

Location of antigenic determinant regions along OmpC of Yersinia species.

Notes: External loops (L1–L8) are indicated by black shading; periplasmic loops and transmembrane β-strands are indicated by light gray shading; and antigenic determinants are indicated by dark gray shading.

Conclusion

The genus Yersinia includes a diverse group of species from environmental isolates (Yersinia aldovae, Yersinia massiliensis, etc.) to pathogens of insects (Y. entomophaga), fish (Y. ruckeri), mammals (Y. frederiksenii, Y. intermedia, and Y. kristensenii), and humans (Y. enterocolitica, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. pestis). In this work, we investigated macro- and microevolutionary processes contributing to the divergence of the ompC gene, which encodes one of the major Yersinia porins. Our findings indicate that the patterns of ompC that change across the genus Yersinia are consistent with those of the shaping of the genus. Positive selection observed in external loops and homologous recombination provided the exchange of novel ompC variants within Yersinia populations. It can be speculated that homological recombination between porin genes is a strategy for the survival of Yersinia species under various stress conditions, such as a new niche, starvation, or bactericides. Taking into account the fact that OmpC is one of the predominant proteins in the outer membrane at a warmblood condition, the identification of antigenic determinants in rapidly evolving regions may indicate the evolutionary mechanisms used by Yersinia species to adapt to the pressures of the host immune system. The results of this study reveal the role of recombination and positive selection in the expansion of adaptability of bacterial populations. Further experiments are needed to establish the role of the individual variants in the pathophysiology of Yersinia.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1. Characteristics of strains and sequences.

Notes: 1Collection of Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Medical Sciences (Vladivostok, Russia). 2Collection of Max von Pettenkofer Institute for Hygiene and Clinical Microbiology, Ludwig Maximilian University (Munich, Germany), represented by bold text.

Footnotes

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Liuyang Wang, Associate Editor

PEER REVIEW: Six peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 1280 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

FUNDING: Work was performed with the financial support of the Russian Science Foundation, project no. 15-15-00035. The authors confirm that the funder had no influence over the study design, content of the article, or selection of this journal.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Paper subject to independent expert blind peer review. All editorial decisions made by independent academic editor. Upon submission manuscript was subject to anti-plagiarism scanning. Prior to publication all authors have given signed confirmation of agreement to article publication and compliance with all applicable ethical and legal requirements, including the accuracy of author and contributor information, disclosure of competing interests and funding sources, compliance with ethical requirements relating to human and animal study participants, and compliance with any copyright requirements of third parties. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: AMS, MPI. Analyzed the data: AMS. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: AMS, EPB. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: AMS, EPB, MPI, AVR. Agreed with manuscript results and conclusions: AMS, EPB, KVG, AVR, MPI. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: AMS, EPB, MPI, KVG. Made critical revisions and approved the final version: AVR, MPI. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sulakvelidze A. Yersiniae other than Y. enterocolitica, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. pestis: the ignored species. Microbes Infect. 2000;2(5):497–513. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loftus CG, Harewood GC, Cockerill FR, Murray JA. Clinical features of patients with novel Yersinia species. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47(12):2805–10. doi: 10.1023/a:1021081911456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litvin VI, Korenberg EI. Natural foci of diseases: the development of the concept at the close of the century. Parazitologiia. 1999;33(3):179–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuter S, Connor TR, Barquist L, et al. Parallel independent evolution of pathogenicity within the genus Yersinia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(18):6768–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317161111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin J, Huang S, Zhang Q. Outer membrane proteins: key players for bacterial adaptation in host niches. Microbes Infect. 2002;4(3):325–31. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01545-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nikaido H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67(4):593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JS, Jung ID, Lee CM, et al. Outer membrane protein A of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium activates dendritic cells and enhances Th1 polarization. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10(1):263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu W, Wang X, Qiu H, et al. Comparative antigenic proteins and proteomics of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica bioserotypes 1B/O:8 and 2/O:9 cultured at 25 °C and 37 °C. Microbiol Immunol. 2012;56(9):583–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2012.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Begic S, Worobec EA. Regulation of Serratia marcescens ompF and ompC porin genes in response to osmotic stress, salicylate, temperature and pH. Microbiology. 2006;152(2):485–91. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castillo-Keller M, Vuong P, Misra R. Novel mechanism of Escherichia coli porin regulation. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(2):576–86. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.576-586.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bystritskaya EP, Stenkova AM, Portnyagina OY, Rakin AV, Rasskazov VA, Isaeva MP. Regulation of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis major porin expression in response to antibiotic stress. Mol Genet Microbiol Virol. 2014;29(2):63–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Ferenci T. An analysis of multifactorial influences on the transcriptional control of ompF and ompC porin expression under nutrient limitation. Microbiology. 2001;147(11):2981–9. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-11-2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thanassi DG, Cheng LW, Nikaido H. Active efflux of bile salts by Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179(8):2512–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2512-2518.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stenkova AM, Isaeva MP, Shubin FN, Rasskazov VA, Rakin AV. Trends of the major porin gene (ompF) evolution: insight from the genus Yersinia. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Isaeva MP, Stenkova AM, Guzev KV, et al. Diversity and adaptive evolution of a major porin gene (ompF) in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;954:39–43. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3561-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9(1):75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delihas N. Annotation and evolutionary relationships of a small regulatory RNA gene micF and its target ompF in Yersinia species. BMC Microbiol. 2003;3:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delport W, Poon AFY, Frost SDW, Kosakovsky Pond SL. Datamonkey 2010: a suite of phylogenetic analysis tools for evolutionary biology. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(19):2455–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin DP, Lemey P, Lott M, Moulton V, Posada D, Lefeuvre P. RDP3: a flexible and fast computer program for analyzing recombination. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(19):2462–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pond SLK, Posada D, Gravenor MB, Woelk CH, Frost SDW. Automated phylogenetic detection of recombination using a genetic algorithm. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(10):1891–901. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin D, Rybicki E. RDP: detection of recombination amongst aligned sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;16(6):562–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.6.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith JM. Analyzing the mosaic structure of genes. J Mol Evol. 1992;34(2):126–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00182389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Posada D, Crandall KA. Evaluation of methods for detecting recombination from DNA sequences: computer simulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(24):13757–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241370698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padidam M, Sawyer S, Fauquet CM. Possible emergence of new geminiviruses by frequent recombination. Virology. 1999;265(2):218–25. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosakovsky Pond SL Frost SDW. Not so different after all: a comparison of methods for detecting amino acid sites under selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22(5):1208–22. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kosakovsky Pond SL, Frost SDW, Grossman Z, Gravenor MB, Richman DD, Leigh Brown AJ. Adaptation to different human populations by HIV-1 revealed by codon-based analyses. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2(6):530–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nei M. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics. New York: Columbia University Press; 1987. pp. 64–111. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1451–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsen JEP, Lund O, Nielsen M. Improved method for predicting linear B-cell epitopes. Immunome Res. 2006;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1745-7580-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen PE, Cook C, Stewart AC, et al. Genomic characterization of the Yersinia genus. Genome Biol. 2010;11(1):R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Millman KL, Tavari S, Dean D. Recombination in the ompA gene but not the omcB gene of Chlamydia contributes to serovar-specific differences in tissue tropism, immune surveillance, and persistence of the organism. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(20):5997–6008. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.20.5997-6008.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haake DA, Suchard MA, Kelley MM, Dundoo M, Alt DP, Zuerner RL. Molecular evolution and mosaicism of Leptospiral outer membrane proteins involves horizontal DNA transfer. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(9):2818–28. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2818-2828.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chevalier S, Bodilis J, Jaouen T, Barray S, Feuilloley MGJ, Orange N. Sequence diversity of the OprD protein of environmental Pseudomonas strains: brief report. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9(3):824–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mussi MA, Limansky AS, Relling V, et al. Horizontal gene transfer and assortative recombination within the Acinetobacter baumannii clinical population provide genetic diversity at the single carO gene, encoding a major outer membrane protein channel. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(18):4736–48. doi: 10.1128/JB.01533-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derrick JP, Urwin R, Suker J, Feavers IM, Maiden MCJ. Structural and evolutionary inference from molecular variation in Neisseria porins. Infect Immun. 1999;67(5):2406–13. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2406-2413.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng Y, Roberts RJ, Kasif S. Identification of genes with fast-evolving regions in microbial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(21):6347–57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen SL, Hung CS, Xu J, et al. Identification of genes subject to positive selection in uropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli: a comparative genomics approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(15):5977–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600938103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petersen L, Bollback JP, Dimmic M, Hubisz M, Nielsen R. Genes under positive selection in Escherichia coli. Genome Res. 2007;17(9):1336–43. doi: 10.1101/gr.6254707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nunes A, Borrego MJ, Nunes B, Florindo C, Gomes JP. Evolutionary dynamics of ompA, the gene encoding the Chlamydia trachomatis key antigen. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(23):7182–92. doi: 10.1128/JB.00895-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qian H, Pang E, Du Q, et al. Production of a monoclonal antibody specific for the major outer membrane protein of Campylobacter jejuni and characterization of the epitope. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(3):833–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01559-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Characteristics of strains and sequences.

Notes: 1Collection of Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Medical Sciences (Vladivostok, Russia). 2Collection of Max von Pettenkofer Institute for Hygiene and Clinical Microbiology, Ludwig Maximilian University (Munich, Germany), represented by bold text.