Abstract

Background

Despite a recent statutory ruling stating the binding nature of advance directives (ADs), only a minority of the population has signed one. Yet, a majority deem it of utmost importance to ensure their wishes are followed through in case they are no longer able to decide. The reasons for this discrepancy have not yet been investigated sufficiently.

Patients and methods

This article is based on a survey of patients using a well-established structured questionnaire. First, patients were asked about their attitudes with respect to six therapeutic options at the end of life: intravenous fluids, artificial feeding, antibiotics, analgesia, chemotherapy/dialysis, and artificial ventilation; and second, they were asked about the negative effects related to the idea of ADs surveying their apprehensions: coercion to fulfill an AD, dictatorial reading of what had been laid down, and abuse of ADs.

Results

A total of 1,260 interviewees completed the questionnaires. A significant percentage of interviewees were indecisive with respect to therapeutic options, ranging from 25% (analgesia) to 45% (artificial feeding). There was no connection to health status. Apprehensions about unwanted effects of ADs were widespread, at 51%, 35%, and 43% for coercion, dictatorial reading, and abuse, respectively.

Conclusion

A significant percentage of interviewees were unable to anticipate decisions about treatment options at the end of life. Apprehensions about negative adverse effects of ADs are widespread.

Keywords: advance directive, living will, decision making, patient’s desires, therapy at the end of life, advanced care planning

Introduction

On September 1, 2009, the third amendment to the German Guardianship Law, known as the Advance Directive Act, came into effect. Even after the passage of the act, the spread of advance directives (ADs) has remained limited.1–6 Even in selected groups, it reaches a maximum of 23%–31%.1,4,6 This is in contrast to the positive attitude of a majority of patients and healthy people, who consider the drafting of an AD for themselves as meaningful and important.7,8 Such limited distribution in spite of the legislation is also being reported from other countries.9–11 For this reason, some authors consider the institution of ADs to have failed.11–13 Only by means of considerable effort, and in specifically selected groups, can the number of people who finally write an AD be increased.12,14,15

Many such directives are unclear and, consequently, of little help.11,13,16 People show considerable insecurity in making decisions for treatment situations that lie in the future.6,16 Ambivalent attitudes toward life-sustaining therapies in critical phases of an illness, or close to the end of a person’s life, appear to be more the rule than the exception. It is unclear whether this is about a professional prejudice among medical staff or a socio-empirically verifiable phenomenon. This implied ambivalence also explains why many people change the contents of their ADs after seeking advice.17

Whether it is fear of possible adverse effects of an AD that discourages people from drawing up such a document has so far not been sufficiently investigated.7 Such barriers have only been identified in a pilot study. In Germany, it is required by the legislature that an AD must relate to specific situations and terms of treatment.18 Otherwise, it is held not to be binding. In that case, health care teams may override what had been laid down in an AD. Moreover, it may be held that in such a case physicians are morally obliged not to follow the written will, but rather to act in the patients’ best interest. Yet, to do so they have to interpret what a patient’s best interests are under a given situation.

However, the existence of ambivalences and fears when filling out an AD is of significant importance. Both of these factors are an obstacle to fulfilling ADs. Moreover, according to the German law, an AD is held only to be binding if its content refers to concrete treatment options. Directives that are worded only in general terms do not have any binding force the law regulates.

Empirical proof of the extent of ambivalences on the part of patients with respect to medical treatment (or its omission) may be of immediate significance to the care of patients at the end of their lives. Such knowledge would also be of value with regard to interpreting ADs in particular in view of the ruling of the German legislature.18 In addition, it may have an impact on the debate about medical practices at the end of people’s lives, such as assisted suicide or euthanasia, which is just rising again in Germany.19

Studies of the barriers that interfere with the practical implementation of what had been laid down in ADs are mainly to deal with the problems of application of ADs, such as the inconsistency of their contents, or the availability of the documents at the time of making a decision, and so forth.6,11,13,20,21 Whether subjective fears are obstructive, and whether people ever consider themselves to be able to make life-changing decisions about the terms of treatment in advance, has not been sufficiently investigated to date, and where investigated it was done only in small samples of the population.22

In the present study, these issues have been investigated in a large sample of 1,260 patients and people who consult health care facilities for various reasons. The study is a part of an extensive investigation into the acceptance of ADs in the light of the German statutory rule. Results on the spread of ADs have already been published.2

Patients and methods

Patients/subjects

Patients and/or people who visited the general practitioners’ clinics, or family doctors specializing in internal medicine, in the Rhine-Main area, were surveyed using a structured questionnaire.20 Surgeries from the wider Rhine-Main area were involved. The participants were informed about the objective and contents of the study by the doctors who were treating them. The questionnaire was anonymized. The patients/people were asked to hand in the questionnaires to the staff in a sealed blank envelope or send it by post.

The questionnaire

The questionnaire was made up of 17 questions, some of them in several parts, and five case histories. It was developed in previous studies7,8,23 and contained a total of 47 items. The questions were particularly concerned with attitudes toward therapy approaches in cases of serious illness and where patients are unable to make their own decisions. There were three answers to choose from: the wish to receive the therapy/to refuse it/do not know.

Fears about any undesirable consequences of an AD, or barriers that may discourage a person from drawing up such a document, were enquired on the basis of three statements, where the respondents could give their views by agreeing or disagreeing.

Those affected could be urged by someone to draw up an AD (coercion).

Doctors could use the directive as the only basis for decision making – and no longer incorporate their specialist knowledge about the prognosis and type of illness in planning the therapy (dictatorial interpretation).

Dependents and surrogates could press for a limit to the therapy, because an AD contains such content, even though the prognosis from a medical point of view may be favorable (abuse by dependents).

In addition, data about demography (age, self-assessment of state of health, marital status [with spouse, life partner, living alone], number and existence of children, age, sex, religion, and educational attainment) and knowledge about, and the existence of, Ads were collected.

Statistics

The statistical calculations were performed at the Institute of Medical Biometry, Epidemiology and Informatics in Mainz, using SPSS program package (IBM® Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The relationship between categorical variables was examined by means of contingency tables and the chi-squared test (and the Fisher’s exact test was used for fourfold tables), with the relationship between ordinal and categorical variables calculated using contingency tables. Furthermore, the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was used for nonparametric distributions, or the Kruskal–Wallis test for more than two categories. Any associations of the answers with age were examined by describing the age distribution for each answer option (in box and whisker plots) and with the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney and the Kruskal–Wallis tests.

Ethics committee approval

The participants were informed about the intentions and the goals of the study in a written statement at the front page of the questionnaire. Participants’ consent was given verbally and was documented by the person who distributed the questionnaire in the respective institution. Verbal consent was considered sufficient as the survey and the evaluation of data were carried out strictly anonymously. The ethics committee of the Medical Council of the State of Hesse, Germany, which is the committee responsible for the review of studies according to German law, has approved the consent procedure and specifically approved this study.

Results

Demographic indications

A total of 1,260 people from 21 surgeries filled in the questionnaires. The important data on demography are summarized in Table 1. Approximately 17.7% of the sample live alone, the majority with partners, children, or other dependents; 15% of the sample have drawn up an AD, and 80% of the sample know about the mechanism of ADs.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Demographic characteristics | n | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, range) | 1,237 | 55.6 years (16–91) |

| Sex (male/female, %) | 1,237 | 38.97/61.03 |

| Religiousness (self-assessment yes/no, %) | 1,232 | 71.27/28.73 |

| Highest educational achievement (%) | 1,231 | |

| Lower secondary education | 24.45 | |

| Higher secondary education | 28.68 | |

| Qualification for university entrance | 9.91 | |

| Completed apprenticeship | 22.1 | |

| University degree | 14.87 |

Table 2 shows self-assessments of the state of health and indications of the frequency of pain. Interviewees were asked to select out of a list of answers – state of health: very good, good, well, poor, very poor; frequency of pain: no, occasional, regularly, permanent.

Table 2.

Self-assessment of health condition and the frequency of pain

| Self-assessment of state of health (n=1,228) |

Self-assessment of frequency of pain (n=1,231) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Numbers, % | 11.64/41.29/36.97/9.28/0.81 | 39.48/41.51/14.46/4.55 |

Therapy preferences when patients are unable to decide for themselves

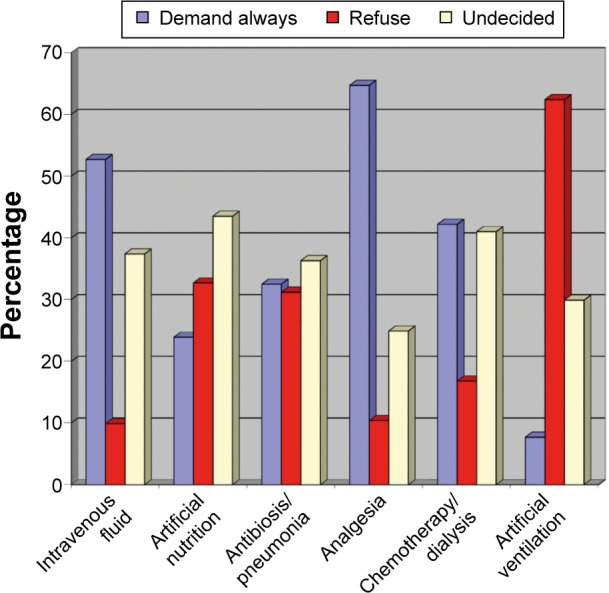

Figure 1 shows the attitudes of the sample toward different therapy approaches in cases of serious illness (ie, non-curable disease and advanced stage) and where patients are unable to make their own decisions (these are intravenous fluid injection; artificial nutrition; antibiosis for pneumonia; analgesia, even if consciousness may be clouded by painkillers; invasive measures such as chemotherapy or dialysis; machine-aided prolongation of life using artificial ventilation). With respect to all treatment options, the number of those undecided ranged from 24.9% (analgesia) to 43.5% (artificial feeding).

Figure 1.

Interviewees’ attitudes toward different therapy approaches in cases of serious illness.

Associations with demographic indications, self-assessment of the state of health and religiousness, educational attainment, and the existence of an AD were calculated alongside the preferences for individual treatment options for each approach. The following observations stand out or are statistically significant:

There was no association between the subjects’ self-assessment of the state of health, frequency of pain, and the attitude toward the given therapy approaches.

There is an association between higher age and the attitude toward the options for intravenous fluid injection, artificial feeding, antibiosis for pneumonia, invasive measures such as chemotherapy or dialysis, and artificial ventilation. Older respondents more frequently refuse these treatments (P<0.0001 for each of these options).

Respondents without ADs are more often undecided about intravenous fluids and artificial feeding. Of the respondents with ADs, 9% wanted artificial feeding. This figure was 34% for those without an AD (P<0.001). Respondents with an AD more frequently refuse antibiotics for pneumonia (P<0.001). Of the respondents with AD, 31% wanted dialysis or chemotherapy compared to 44% without an AD (P<0.001). Machine-supported ventilation was refused by 84% of the respondents with AD, compared to 59% of those without an AD (P<0.0001).

The desire to receive intravenous fluids is associated with a higher formal educational attainment; 64.97% of university graduates demand this, whereas only 42.12% of lower secondary school leavers want intravenous fluid injection (P<0.005).

People who live on their own exclude invasive dialysis or chemotherapy measures more frequently than people who live together with a partner or dependents (P<0.001).

The number of respondents differed among the questioned treatment options (intravenous fluid, n=1,215; artificial nutrition, n=1,215; antibiosis for pneumonia, n=1,218; analgesia, n=1,222, invasive measures such as chemotherapy or dialysis, n=1,220, machine-aided prolongation of life using artificial ventilation, n=1,225).

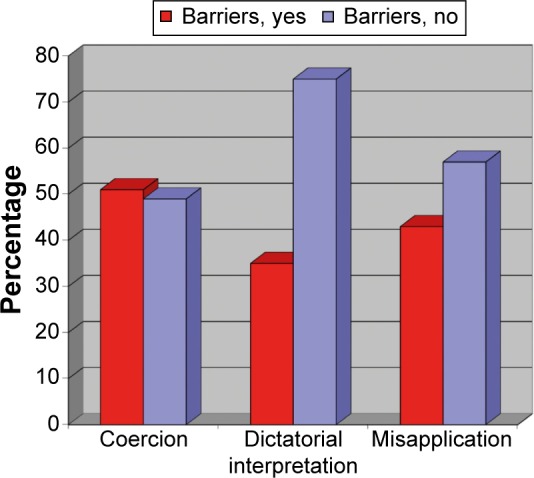

Barriers against fulfilling an AD

Figure 2 shows the frequency of emotional (subjective) barriers associated with fulfilling an AD.

Figure 2.

Frequency of emotional (subjective) barriers associated with fulfilling an AD.

Abbreviation: AD, advance directive.

Figures in percentage for the response yes/no regarding three types of negative consequences attributed to fulfilling an AD.

Discussion

To date, this study is the most extensive socio-empirical examination into the attitudes of patients and people toward therapy options with advanced illnesses and incapability to decide, as well as into fears of possible negative consequences from the presence of an AD. It explains the discrepancy observed to date in Germany and the US, for example, between the significance attached to the mechanism of an AD in public surveys and its rather limited distribution.5,7,8,10,11 The spread of ADs in the sample surveyed in this study corresponds with that in other investigations.2,3,6,10 The majority of the sample know about the mechanism of ADs (data not shown in this article).

The sample surveyed is not representative of the population of the Federal Republic of Germany. But a representativeness for people who seek help in health services can be assumed. It is, however, plausible to assume that interest in, and knowledge of, ADs is more widespread in the group that has been investigated than in the general population. The obstructions and barriers shown in this study toward fulfilling an AD are probably even more widespread in the population as a whole.

The number of patients/people who consider themselves to be uncertain is significant for all the therapy options given in the questionnaire (artificial feeding, antibiotic therapies for pneumonia, dialysis, and chemotherapy).

The “administration of intravenous fluids” is desired by a majority of respondents. Probably the administration of fluids is considered necessary for satisfying a feeling of thirst. The fact that, depending on the medical situation, intravenous fluids can also painfully lengthen the dying process obviously remains unconsidered in this investigation. In these cases, feeling thirsty can be satisfied in other ways (by moisturizing the mucous membranes, etc).

The results show that, for many people, stipulating certain therapy approaches is exceptionally difficult and that a decision made in advance is hardly ever possible, in particular, in the light of the German law demanding provision for concrete treatment options.11,16,22 This is consistent with the empirically found tendency, preferably not to follow decrees in the directives of other people.23

Pain management is, as expected, desired by an overwhelming majority of the respondents. In this investigation too, however, one-third of the respondents are also unsure or refuse this completely in cases where a clouding of consciousness is anticipated. This discovery had already been ascertained in an earlier investigation of a small number of people which included a group of tumor patients.22 Approval of a pain management therapy that potentially clouds consciousness cannot be assumed for all patients. It is much more important to find out the wishes of the individuals concerned. These results suggest that the capacity for self-determination is rated higher than total freedom from pain.

In particular, these results are of importance in the light of the regulations in the German Advance Directive Act. This demands a specification of therapy measures that are desired or refused.18 This appears not to be possible for large number of people. This fact may justify physicians’ decision to override what had been laid down in an AD. On the other hand, overriding an AD is in contradiction to the very idea of AD which is meant to enhance patient’s self-determination. Hence, our findings support efforts to educate persons before fulfilling an AD.

We have found no association between respondents’ current state of health and the self-assessment of their religiousness in their answering behavior. Knowledge of the religious background of people who are undergoing treatment does not allow any inferences to be drawn concerning their attitude toward therapy approaches.

Higher age is more closely associated with a rejection of particular therapy options. This observation corresponds with the clinical and practical experience gained in other studies.1,2,21,24 This discovery also supports the efforts undertaken in pilot projects to offer support in the decision-making process to the elderly in retirement homes, and to chronically ill people, regarding medical treatments (including emergency care).12,13,25 Yet, younger people also benefit from guidance in drawing up ADs. Schöffner et al17 have shown the influence of a consultation over several hours on the contents and design of ADs. The German Advance Directive Act does not allow for any obligatory consultancy before drawing up such a will. Yet, this is urgently advisable in view of the uncertainties shown up by this study.

The study also confirms in a large sample of respondents the significant spread of subjective barriers associated with ADs. This is in line with the findings made by our group in a preliminary study.7 A majority of interviewees fear that they could be coerced into drawing up such a document. One-third of the respondents see the danger that decrees laid down in an AD are implemented without being checked by the medical team, even if they could contradict the current best interests of their patient (dictatorial interpretation). In addition, >40% of the respondents consider that abuse by dependents is also possible. The spread of such fears has so far been completely underestimated.

The results of this study provide an explanation for the limited spread of ADs. As a consequence, efforts to implement strategies such as advance care planning seem warranted.16 Advance care planning offers attendance by caregivers in making decisions for future care. The concept has now become an established strategy to improve care for particular groups of patients.26 In the Western world, most people die in consequence of chronic illnesses. The worsening of such conditions, typical complications, and complexes of symptoms are foreseeable in the majority of cases. Hence, advance care planning provision needs to be integrated in the context of attending people with chronic illnesses. As studies have shown, the initiative to do this must come from doctors.12,16,21,22 This makes a change in the culture of medicine urgently necessary. Advance care planning may help to bypass barriers such as those found in our study.

A forward-looking discussion about the extent of treatment as well as about treatment options to be expected in the future, based on people’s current state of health and illness and prompted by attending caregivers, is an appropriate provision for future care. This approach should become a standard element of medical practice. Any written decrees could be helpful as part of the communication necessary for this.

Recognition of the mechanism of power of attorney over health issues must be seen as a further extremely significant alternative. Investigations show only a limited level of awareness of this option in Germany, among both patients and medical staff (nurses, carers, and doctors). And yet, patients predominantly wish for a representative decision made by people who have their trust, in combination with the team of doctors who are carrying out the treatment, as has been shown in one study.27 In case an AD is held to be too ambiguous, the presence of a health care proxy who may serve as a patient’s advocate is preferable to the alternative of but overriding an AD by health care teams. The results of our study support the idea of appointing health care proxies.

The strength of this study is in the size of the sample of respondents. No other investigation has been carried out into the issues around the barriers, and attitudes, to therapy options at the end of people’s lives with such a large number of respondents. A further strength is in its methodical approach. No interviews were carried out by a person who could influence the answers in accordance with any perceived social desirability. Instead, this survey was carried out without the influence of any interviewers.

There is a limitation, however, in the heterogeneity of the group. It can be assumed that patients with a specific experience of illness, including experience of advanced illness, have a different attitude toward decisions about therapy options made in advance than people who seek health care in a less threatened state of health. This assumption is supported by the fact that older people have a more negative attitude toward the majority of therapy options.

Conclusion

This study shows that a great uncertainty can be anticipated among people making therapy decisions in advance. Over and above that, it shows that there is a wide distribution of subjectively perceived barriers. Such barriers can only be overcome through open and honest communication within therapeutic relationships.28 A process of extensive advance care planning is recommended in this study, along with the nomination of a person with power of attorney over health issues, as alternative ways to ensure self-determination at the end of people’s lives.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Driehorst F, Keller F. Advance directives in patients with kidney disease or other general medical diagnoses. Deutsch Med Wochenschr. 2014;139:633–637. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1369881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sahm S, Hilbig J. Nach dem Gesetz: Akzeptanz und Verbreitung von Patientenverfügungen bei Tumorpatienten [According to the law: Acceptance and spread of advance directives in tumor patients] Zeitschr Med Ethik. 2013;59:283–295. German. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graw JA, Spies CD, Wernecke KD, Braun JP. Managing end-of-life decision making in intensive care medicine – a perspective from Charité Hospital, Germany. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e46446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hubert E, Schulte N, Belle S, et al. Cancer patients and advance directives: a survey of patients in a hematology and oncology outpatient clinic. Onkologie. 2013;36:398–402. doi: 10.1159/000353604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Oorschot B, Schuler M, Simon A, Flentje M. Advance directives: prevalence and attitudes of cancer patients receiving radiotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(11):2729–2736. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1394-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brokmann JC, Grützmann T, Pidun AK, et al. Vorsorgedokumente in der präklinischen Notfallmedizin [advance directives in prehospital emergency treatment: prospective questionnaire-based analysis] Anaesthesist. 2014;63:23–31. doi: 10.1007/s00101-013-2260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sahm SW, Will R, Hommel G. Attitudes towards and barriers to writing advance directives amongst cancer patients, healthy controls and medical staff. J Med Ethics. 2005;31:437–440. doi: 10.1136/jme.2004.009605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahm S, Schröder L. Verbreitung von Patientenverfügungen und stellvertretende Entscheidung durch Angehörige: Präferenzen für die Entscheidung am Lebensende – eine empirische Untersuchung [Dissemination of advance directives and decision making by proxies: Preferences for decisions at the end of life – an empirical investigation] In: Frewer A, Fahr U, Rascher W, editors. Jahrbuch Ethik in der Klinik Band 2. Königshausen & Neumann; Würzburg, Germany: 2009. pp. 89–108. German. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gina K, Gill G, Fukushima E, Abu-Laban RB, Sweet DD. Prevalence of advance directives among elderly patients attending an urban Canadian emergency department. Can J Emergency Med. 2012;14:90–96. doi: 10.2310/8000.2012.110554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartog CS, Peschel I, Schwarzkopf D, et al. Are written advance directives helpful to guide end-of-life therapy in the intensive care unit? A retrospective matched-cohort study. J Crit Care. 2014;29:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough. The failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34(2):30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.In der Schmitten J, Lex K, Mellert C, Rothärmel S, Wegscheider K, Marckmann G. Implementing an advance care planning program in German nursing homes: results of an inter-regionally controlled intervention trial. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(4):50–57. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marckmann G, In der Schmitten J. Patientenverfügungen und advanced care planning: Internationale Erfahrungen [Advance directives and advanced care planning: International Experiences] Zeitschr Med Ethik. 2013;59(3):229–243. German. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silvester W, Fullam RS, Parslow RA, et al. Quality of advance care planning policy and practice in residential aged care facilities in Australia. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3:349–357. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vandervoort A, Houttekier D, Vander Stichele R, van der Steen JT, Van den Block L. Quality of dying in nursing home residents dying with dementia: does advanced care planning matter? A nationwide postmortem study. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahm S. Sterbebegleitung und Patientenverfügung [Terminal care and advance directives] Frankfurt: Campus; 2006. pp. 154–159. German. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schöffner M, Schmidt KW, Benzenhöfer U, Sahm S. Patientenverfügung auf dem Prüfstand: Ärztliche Beratung ist unerlässlich [Advance directives put to test: Medical counseling is indispensable] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2012;137:487–490. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298998. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Höfling W. Das neue Patientenverfügungsgesetz in der Praxis – eine erste kritische Zwischenbilanz [The new advance directive law - silver bullet for a self-determined pass away? The new advance directive law in practice- a first interim balance sheet] Baden-Baden: Nomos; 2011. Das neue Patientenverfügungsgesetz – Königsweg zum selbstbestimmten Sterben? pp. 11–16. German. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahm SW. Palliative care versus euthanasia. The German position: the German General Medical Council’s principles for medical care of the terminally ill. J Med Philos. 2000;25(2):195–219. doi: 10.1076/0360-5310(200004)25:2;1-O;FT195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ledoux M, Rhondali W, Monnin L, Thollet C, Gabon P, Filbet M. Advanced directives. Nurses’ and physicians’ representations in 2012. Bull Cancer. 2013;100:941–945. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2013.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spoelhof GD, Elliott B. Implementing advance directives in office practice. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:461–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahm SW, Will R, Hommel G. What are cancer patients’ preferences about treatment at the end of life? A comparison with healthy people and medical staff. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(4):206–214. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0725-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahm S, Will R, Hommel G. Would they follow what has been laid down? Cancer patients’ and healthy controls’ views on adherence to advance directives compared to medical staff. Med Health Care Philos. 2005;8(3):297–305. doi: 10.1007/s11019-005-2108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snyder S, Hazelett S, Allen K, Radwany S. Physician knowledge, attitude, and experience with advance care planning, palliative care, and hospice: results of a primary care survey. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30(5):419–424. doi: 10.1177/1049909112452467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Schols JM, van der Sande FM, Frenken LA, Wouters EF. Insight into advance care planning for patients on dialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(1):104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song MK, Ward SE, Fine JP, et al. Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making in dialysis: a randomized controlled trial targeting patients and their surrogates. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(5):813–822. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sahm SW, Will R. Angehörige als natürliche Stellvertreter. Eine empirische Untersuchung zur Präferenz von Personen als Bevollmächtigte für die Gesundheitsvorsorge bei Patienten, Gesunden und medizinischem Personal [Relatives as natural proxies. An empirical investigation regarding personal preferences as health care proxies in patients, healthy people and medical staff] Ethik in der Medizin. 2005;17:7–20. German. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narang AK, Wright AA, Nicholas LH. Trends in advance care planning in patients with cancer: results from a national longitudinal survey. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(5):601–608. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]