abstract

As multicellular organisms evolved a family of cytoskeletal proteins, the keratins (types I and II) expressed in epithelial cells diversified in more than 20 genes in vertebrates. There is no question that keratin filaments confer mechanical stiffness to cells. However, such a number of genes can hardly be explained by evolutionary advantages in mechanical features. The use of transgenic mouse models has revealed unexpected functional relationships between keratin intermediate filaments and intracellular signaling. Accordingly, loss of keratins or mutations in keratins that cause or predispose to human diseases, result in increased sensitivity to apoptosis, regulation of innate immunity, permeabilization of tight junctions, and mistargeting of apical proteins in different epithelia. Precise mechanistic explanations for these phenomena are still lacking. However, immobilization of membrane or cytoplasmic proteins, including chaperones, on intermediate filaments (“scaffolding”) appear as common molecular mechanisms and may explain the need for so many different keratin genes in vertebrates.

KEYWORDS: 14-3-3, Akt, apoptosis, atypical PKC, cell signaling, cytokines, Hsp40, Hsp70, inflammation, innate immunity, NF-kB, tight junction

Epithelial barriers, cytoplasmic intermediate filaments and innate immunity co-evolved with multicellularity in metazoans

Epithelial barriers represent the earliest tissues organized in metazoans.1,2 The early development of cell-cell contacts sealing the paracellular route and polarized distribution of membrane proteins3 and cytoskeleton4 are characteristic of epithelia and common to all metazoan. From a functional standpoint, epithelial barriers provided early metazoans with the evolutionary advantage of defining an internal milieu, different from external sea or fresh water, and digestive cavity (e.g. in Cnidarians) enabling them to catch and digest bigger prey.4

Along with the increased complexity of the multicellular organisms, various molecular mechanisms and cellular structures co-evolved in metazoans. In this review, we will address the role of cytoplasmic intermediate filaments (IF),5 and specifically keratins (K), which diverged from an ancestral lamin at the origin of metazoan lineages.6 We will focus on the poorly recognized relationship between keratins and atypical PKC (aPKC), a component of the PARtition defective (Par) proteins or Par complex, which is essential for the acquisition of apico-basal polarity in epithelia,7 first discovered in C. elegans.8 We will review evidence indicating a more general role of keratins in protection from chemically-induced apoptosis, and regulation of other signaling pathways. Finally, larger, more complex, multicellular organisms also faced the challenge of attacks by single-celled organisms and viruses. Accordingly, innate immunity pathways evolved along with multicellularity9 as a defense. A growing body of evidence suggest that keratin IF, and innate immunity interact in vertebrate epithelial barriers. Some of these interactions, which are possibly based on ancient evolutionary advantages for barrier function, are involved in pathophysiological mechanisms in human disease.

Keratins, mechanical is not mechanistic

Cytoplasmic IF are represented by keratins (type I and II) in epithelia. So far, 28 keratin genes (Krt) have been identified in the human genome, not counting the hair keratins. Keratin proteins (K) are obligate heterodimers of type I (13 genes) and type II (15 genes). All keratins display a central rod domain, involved in dimerization, and globular head and tail domains.5 Filament formation requires, minimally, the expression of one type I and one type II keratin genes. Usually, more than two keratin genes are transcribed. In the adult, the hepatocytes are the archetypal example where only one type I (K8) and one type II (K18) are expressed.10,11 Table 1 schematically summarizes the expression of type I and II keratins in tissues mentioned in this review. For a comprehensive description of keratin expression patterns see.11,12

Table 1.

Keratin expression in tissues described in this review.

| Epithelium | Cell type | Type I | Type II | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple | Hepatocytes | K18 | K8 | 12 |

| Intestine crypt | K18 K19 K20 K23 | K8 K7 | 131 | |

| Intestine villus | K18 K19 K20 | K8 | 95 | |

| Pancreatic ducts | K18 K19 | K4 K8 K7 | 132 | |

| Stratified | Epidermis basal | K14 K15 K17 | K5 K6 | 11 |

| Epidermis suprabasal / spinous | K16 K10 | K6 K1 K2* | 11 | |

| Mammary gland duct | K14 K17 K18 K19 | K5 K7 K8 | 11 |

Note.

Epidermis spinous/granular

As it is the case for other IF proteins, keratins are subjected to several post-translational modifications including phosphorylation, glycosylation, acetylation and sumoylation. These modifications control assembly / disassembly of the filaments, function, and subcellular distribution (reviewed in.13).

There are many differences in the biology of IF as compared with better-known microtubules and actin. IF are not polarized and there are no molecular motors using IF as substrates. Importantly, there are no IF in common model organisms such as yeast and flies, which yielded an early wealth of knowledge in the tubulin and actin fields. In addition, the insolubility of IF makes co-immunoprecipitation very difficult. Furthermore, with the exception of withaferin A,14 drugs specifically affecting IF are lacking. Efforts to find drugs that correct the effects of keratin mutations by high-throughput screens are currently under way 15 and may yield novel pharmacological tools for keratin IF.

Because of the difficulties indicated above, knockout mouse models and knockdown of keratins in tissue culture cell lines have been the major molecular approaches available for functional studies of IF. Even those approaches are not straightforward. Knockout models are often embryonic lethal, such as the K8 knockout mouse in the C57B1/6 background (94% penetrance, 16) or the pan-keratin II knockout mouse.17 In other cases, keratin deficient mice showed very subtle phenotypes, possibly because of the keratin redundancy, for example, the K7 knockout.18

The mechanical function of keratin IF is textbook knowledge. It is self-evident in the epidermis, as well as in the mechanical characteristics of isolated keratin IF in vitro.19 Epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS) is the paradigm of a mechanical disorder caused by mutations in K5, K14,20 and in a few cases plectin, a keratin linker protein.21 Shear stress on the epidermis causes blistering in these patients. Some features of the K14 mutations phenotype, however, seem to suggest that there are possible non-mechanical mechanisms involved. The R125P K14 mutation elicits JNK signaling.22 Mutant K14 increases TNFα secretion and sensitivity.23 Those observations were recently highlighted by findings of increased caspase 8 both in lesional and non-lesional areas in EBS patients24 which suggests the mutations have additional consequences beyond a simple break of cells. Moreover, evidence from the Magin lab supports the notion that expression of the R125P K14 alone makes cells mechanically weaker than cells lacking keratins altogether.25 Furthermore, data from Marceau lab suggest that in internal epithelia, keratins 8/18 contribute to cell stiffness via cortical actin, by activation of the ROCK signaling pathway.26 This suggests that even mechanical properties may be partially explained by a signaling function. Finally, to help maintain the barrier together, keratins attach to desmosomes, which represent a critically important intercellular junction, and provide adhesive force to keep epithelial cells together. This will be reviewed in a separate section.

Conversely, extensive analysis of various keratin knockout models has shown that IF play non-mechanical functions, providing epithelial cells with protection against stress not related to deformation due to external forces (e.g., chemical stress). In the following sections we will review some of the consequences of loss, mutation, or overexpression of keratins in epithelial barriers. They comprise highly interlinked effects on apoptosis or survival, innate immunity, intracellular signaling, and apico-basal polarity.

Keratins protect liver, placenta, and skin epithelia from apoptosis

The first piece of evidence linking keratins with protection of epithelia from apoptosis came from the K8 knockout mouse. The high mid-gestational mortality in these animals is due to apoptosis in the liver and the placenta, more specifically, in the giant trophoblast cell layer. More importantly, the defect could be rescued by TNFα-deficient mothers or TNFR2-null offspring.27,28 In fact, K8 or K18 deficient cells were found to be two orders of magnitude more sensitive to TNFα-induced apoptosis.27 K18 provides resistance to Fas-mediated liver failure, but not through common apoptotic mechanisms.29 These early surprising findings were reproduced in other systems as well. K17 null mice showed apoptosis in hair matrix cells,30 which is also TNFα-dependent.31 Lack of one allele of K14 also results in hypersensitivity to TNFα, keratinocyte apoptosis, and Naegeli-Franceschetti-Jadassohn syndrome.32 In summary, it is important to highlight that in all these cases the stress is TNFα (that is “chemical stress”), not mechanical.

It seems appropriate to emphasize that the effect of keratin deficiency on apoptosis is different in the intestinal epithelium, as compared to the liver or the skin. No increases in the rate of apoptosis or necrosis were observed in K8 null small intestine enterocytes.33 Moreover, a paradoxical resistance to apoptosis, which seems to be dependent on microbiota, was found in colonocytes in the same animal model,34 suggesting tissue-specificity for this function of IF.

Not only keratin knockout, but also mutations result in changes in susceptibility to apoptosis. Overexpression of K18 R89C mutant predisposes hepatocytes to Fas- but not TNF-mediated apoptosis.35 Conversely, in epidermis, expression of K10/14 chimeras increase predisposition to skin cancer by suppression of apoptosis.36

The role of keratins in the protection of epithelial cells from apoptosis has translational significance. Exonic mutations in K8 and 18 predispose to liver chemical injury. Patients with severe amoxicillin-clavulanate, isoniazid or nitrofurantoin drug induced liver injury showed specific keratin mutations,37 acute liver failure,38 and primary biliary cirrhosis.39 It is not surprising that keratin mutations predispose to injury in the liver: Unlike in other epithelia, there is no keratin redundancy in hepatocytes cells.

Molecular mechanisms involved in IF-mediated epithelial protection

Mechanistic studies of the roles of keratin IF in epithelial cell survival are far from complete. The broadly accepted interpretation of the available evidence is that IF, which represent abundant insoluble structures, provide a solid surface to bind and immobilize proteins which would be otherwise soluble in the cytosol. This phenomenon is generally referred to as “scaffolding.” IF scaffolding sequesters several proteins away from the locations where they should fulfill their functions such as the cytosol, the inner surface of the plasma membrane, or the vicinity of specific receptors. It is generally assumed that proteins attached to the IF scaffold are not functional. However, in the case of Hsp70 chaperones (discussed below), we have found that scaffolding modifies or even enhances function. For the anti-apoptotic function of keratin IF, several proapoptotic proteins were found attached to the IF scaffold and released upon specific signaling. In the absence of IF, such as in K deficient mouse models, the same proteins would be readily available in the cytosol. IF scaffolding was shown for TRADD,40 c-Flip,41 DEDD,42 caspases,43 and Pirh2, a RING-H2-type ubiquitin E3 ligase.44 Other, as yet not fully understood mechanisms include a switch to a FasR-mediated apoptosis and possible disruption of lipid rafts.45

Although no specific evidence currently supports possible synergy among these mechanisms, in theory, they are not mutually excluding. The molecular details of protein binding to keratins are also unclear. Direct interactions with keratin domains have been shown for proteins such as TRADD to the K18 and 14 head domain.40 On the other hand, many keratin binding proteins have been discovered, including chaperones,46-49 plectin (epiplakin 1), a cytoskeletal linker,50 and desmosomal proteins 51 among others, which greatly increase the number of potential binding sites to indirectly attach proteins to the keratin IF. Accordingly, the protein-protein interactions involved in the IF scaffold are complex and far from fully understood.

Keratins in protein chaperoning

Early studies found several chaperones associated to the IF scaffold: Hsp70 isoforms 48 are tightly attached to keratin IF.52 Likewise some members of the Hsp40 family bind stably to the C-terminal region of K18.46 Small cochaperones, such as Bag1 also bind to the IF scaffold under pro-inflammatory upregulation.53 Filensin IF bind α-crystallin.54 Hsp74 is directly attached to K1 in the urinary bladder epithelium,55 and Hsp27 interacts with keratin tetramers.56

Because the IF scaffold is generally thought to be a sink that prevents proteins from carrying their normal function (e.g. TRADD, mentioned above), the first question that comes to mind is whether or not keratin-bound chaperones are functional. When purified keratin IF containing Hsp70 and Hsp40 are used in a standard luciferase refolding assay to measure Hsp70 chaperoning activity, they can refold chemically denatured luciferase at a similar rate as soluble (cytosolic) Hsp70.52,53

By subcellular fractionation, it was determined that Hsp70/40 chaperones exist in both soluble (cytosolic) and IF-bound forms. The latter represents approximately 10% of the total cellular chaperone in epithelial cells in culture.52 This apparently modest fraction epitomizes an emerging question about the quantitative significance of the IF scaffold. For any of the proteins attached to the IF scaffold, is immobilization on IF sufficient to affect overall cellular function? Multiple independent pieces of evidence seem to be required to answer this question. There is at least one example of an Hsp70/40 substrate (“client”) which fulfills multiple criteria leading to the conclusion that IF-associated chaperoning can exclusively refold some proteins which the cytosolic counterpart does not process. PKCs (including “atypical” aPKC) are refolded (rescued) by Hsp70 chaperones which bind a conserved site on PKC partially overlapping the turn motif57 (reviewed in58). The steady-state levels of aPKC are deeply decreased in K8 deficient enterocytes that is in cells where loss of IF is complete (no redundant type II keratin) and increased in K8 transgenic overexpressers.52 Likewise, the half-life of aPKC is decreased nearly 7-fold in cultured epithelial cells under K8 knock-down. In that case, there are no transcriptional or translational changes in the expression of the protein.52 In vitro, after subcellular fractionation, cytosolic extracts lacking IF, which maintain full luciferase refolding capacity, failed to refold aPKC. Conversely, keratin IF also active in luciferase refolding were capable of aPKC refolding when supplemented with PDK1, the kinase that stabilizes aPKC active conformation.59 In summary, the keratin scaffold with its associated proteins is necessary and sufficient to carry out aPKC refolding.

The presence of chaperones on the IF scaffold may have three possible functions. First, they are involved in chaperoning keratins themselves 60-62 and, accordingly, also associated with misfolded keratin aggregates, such as Mallory-Denk bodies in alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.63 Second, IF attached chaperones may bind misfolded, inactive proteins, thus enhancing the binding capacity of the IF scaffold to peptides that would not bind directly to keratins. Examples of tight binding of not fully folded proteins to keratin IF have been reported.64 However, the role of chaperones and the functional effects of this type of scaffolding sink remain unclear: In each case the fate of proteins attached to the IF scaffold needs to be established. The third type of function includes active chaperoning of specific proteins, epitomized by aPKC. It is uncertain how many other proteins may require specific folding at the IF scaffold. Data on steady-state protein levels of a group of kinases, including Akt, which are known to be clients of Hsp70/40, showed changes under K8 knockdown. Therefore, there is an indication that other kinases, in addition to aPKC, may be dependent on IF.52 Accordingly, it is possible that a keratin/Hsp70–40 complex may regulate other signaling pathways through kinase stability.

Keratins in signaling

The effects of keratin expression on signaling pathways are among the most intriguing features of IF. Quite possibly, it is one of the central functions of IF in the regulation of epithelial barriers. Yet, it is one that remains very poorly understood. Examples of profound signaling changes induced by keratin deficiency or mutations abound and are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Examples of effects of changes in keratin expression or keratin mutations on signaling pathways.

| Affected keratin(s) | Effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| K19 knockdown | Enhanced Akt signaling (decreased PTEN) | 133 |

| K19 knockdown | Destabilization of HER2 / decreased ERK | 134 |

| K5 and 14 mutations | Epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS) rescued by ERK inhibition | 135 |

| K17 overexpression | Activates Akt signaling in Ewing sarcoma | 136 |

| K17 overexpression | Activation of transcriptional regulator AIRE | 106,137 |

| K17 knockdown | Decreased pTyr-23 annexin A2 | 138 |

| K14 knockdown (and decreased partner K5) | Decreased pAkt and enhanced Notch1 | 139 |

| K14 overexpression | Increased JNK-MAPK signals | 22 |

| K8/K18 or K8/K19 overexpression | Raf-1 is released from 14-3-3 by stress | 80 |

| K8 null hepatocytes | Fas-activated apoptosis mediated by DEDD | 140 |

| K8 null hepatocytes | Inactive p38 MAPK, p44/42 MAPK and JNK1/2 are released from IF upon activation during apoptosis | 141 |

| K8 knockdown | Increased PI3K/Akt activation | 142 |

| K8 knockdown | Protein kinase C, cell adhesion and migration | 45 |

| K8 null mouse and K8 knockdown | Post-translational downregulation of aPKC via Hsp/Hsc70 | 33,52 |

| K18 knockdown | MacroD1 (LRP16) retention in the cytoplasm | 143 |

| K17 knockout | Increased TNFR – NF-kB activity through TRADD | 31 |

| Global type I or II keratin knockout: rescue by expression of K6/K17 or K5/K14 | Increased PKCα activity, desmosome destabilization | 92 |

| Global type II keratin knockout | GLUT1 – 3 mislocalization, AMPK and mTOR activation | 113 |

| Global type II keratin knockout | Increased EGFR and PKCα-dependent Erk1/2 signaling | 112 |

| Global type II keratin knockout | Rack1-keratin interactions modulate PKC-α signaling | 144 |

Note. Bolded protein names indicate evidence for binding to keratin IF (scaffolding). Knockdown refers to RNAi manipulation in cell lines. Overexpression indicates vector-mediated transcription in cell lines.

Some of the signaling pathways affected by keratin loss or mutations are also involved in the development and maintenance of tight junctions (TJ). That is the case of aPKC in the PAR “polarity complex.”65-67 Likewise, ERK1/2 controls expression of TJ proteins,68 and junction formation.69,70 Furthermore, JNK has been shown to be part of a pathway that modulates trans-epithelial resistance 71 and ZO-1 assembly.72 Loss of K76 results in increased skin permeability via loss of claudin 1.73 Finally, IF-dependent changes in intracellular signaling are consistent with increases in epithelial Dextran 3000 permeability 52 in the intestine. In brief, changes in signaling pathways represent poorly studied links between keratin IF and epithelial barrier function.

The mechanistic details of how keratin defects or mutations modulate cellular signaling are still unclear and will need additional investigation. A few hypotheses, such as those that follow, may have to be tested for each specific signaling effect of keratin.

14-3-3 proteins bind phospho-peptides to sequester kinases or their substrates (reviewed by 74). 14-3-3ζ, ϵ and σ have been shown to bind keratin IF.75-78 14-3-3 proteins bind keratins through their phosphorylated sites.75 However, 14-3-3 are dimers with two aligned phosphorylated domain binding sites on the sides of a central channel. Accordingly, 14-3-3 dimers can scaffold two different proteins,79 or, in this case bring another phosphoprotein to the IF scaffold. An example of this mechanism is the attachment of the Raf-1 kinase to the IF scaffold, mediated by 14-3-3. Under oxidative stress, Raf-1 phosphorylates keratin and is released from the scaffold.80

Mechanotransduction

Keratinocytes are under frequent and potentially strong mechanical stress. Mechanotransduction involves calcium influx as well as phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor, and ERK1/2.81(reviewed by 82). In lung-derived cells, more subtle shear stress induces changes in IF that depend on aPKC activation.83 Accordingly, defects in mechanical properties of these cells due to keratin deficiency may induce signaling changes. The role of mechanical stress and mechanotransduction is more difficult to conceptualize in cells subjected to comparatively very minimal mechanical stress, such as hepatocytes or epithelial cells in culture. Nonetheless, studies of how changes in mechanical properties of the keratin-deficient cells may result in further downstream changes in PKC, Akt, ERK, or JNK-MAPK signaling seem to be warranted. At this time, effects of mechanotransduction on other signaling effects cannot be ruled out for most of the consequences of keratin deficiency reviewed here.

Chaperoning

In a previous section we already discussed how keratin-associated chaperones maintain steady-state levels of aPKC. Whether or not similar keratin-dependent mechanisms are involved in maintaining the normal folding of other kinases, or preventing their degradation, remains a testable hypothesis.

In summary, there is extensive experimental evidence supporting the notion that a group of pro-survival and stress-response signaling pathways require normal keratin IF. Possible mechanistic explanations for this requirement are multiple and additional data will be necessary to identify how and to what extent keratins affect specific kinase (or phosphatase) activities. In the next sections we will discuss the role of keratin IF in specific signaling pathways involved in desmosome assembly and innate immunity response.

Keratins and intercellular bonds in epithelial barriers: Is desmosome function dependent on if expression?

Keratin IF are anchored to the cell surface at desmosomes mediating attachment to the neighboring cells through desmocollin and desmoglein.51 Keratin IF also connect to hemidesmosomes, which attach epithelial cells to the extracellular matrix at the basal membrane through integrin β4.84 There is no question that desmosomes and hemidesmosomes are important for epithelial barrier integrity. For example, in the skin and mucosae, autoantibodies against desmosome (desmogleins in pemphigous) and hemidesmosome (in pemphigoid) surface proteins, are associated with autoimmune blistering disease.85 Mutations in desmosomal proteins result in arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathies and in skin syndromes (reviewed by86). The “Ogna type” epidermolysis bullosa simplex is caused by a missense mutation in plectin, which links keratin IF to the hemidesmosome plaque.87

Because of the tight association of IF to desmosomes and hemidesmosomes, it seems natural to ask whether or not filamentous keratins are necessary for the assembly and function of these junctions. Published evidence suggest mixed answers to this question.

K8-null embryonic cells88 and K18-null hepatocytes89 lacking IF still, display desmosomal plaques with normal ultrastructure, except, of course, for the absence of filaments. This is consistent with the current model of desmosomal assembly, which involves e-cadherin induced recruitment of desmoplakin and desmogleins, localized activation of PKCα followed by IF attachment at a late phase (reviewed by84). Conversely, keratin null keratinocytes display scattered plectin and hemidesmosome components, along with faster cell migration,90 suggesting that keratin binding is necessary for hemidesmosome plaques to coalesce. This view of desmosome formation independent of IF, however, was recently challenged by evidence showing that specific deletion of K1/K10 (skin “differentiated” suprabasal keratins) results in smaller desmosomes with decreased amounts of desmoplakin and desmocollin, but normal plakoglobin.91 This intriguing dependence of desmosome structure on specific keratin types, was recently clarified by data from Magin lab using global type I or type II keratin cluster knockout mouse keratinocytes, rescued by lentiviral-mediated expression of either K14 or K17. The resulting keratinocytes express all the keratins of the non-targeted cluster, and are rescued by lentiviral-mediated expression of one keratin of the knockout cluster. Cells expressing K14/K5 pairs displayed normal desmosomes. On the other hand, cells expressing K17/K6 pairs showed fragmented, less-stable desmosomes. Interestingly, the difference does not seem to be related to mechanical anchoring of the desmosome plaque to the filaments, but rather to the ability of K5/K14 IF to maintain PKCα away from the plasma membrane, possibly in an inactive conformation.92 This is, therefore, another instance where the signaling function of the filaments is mechanistically prevalent over mechanical interactions.

Keratins in innate immunity and inflammation

Like for other signaling events, there is a growing body of publications reporting multiple roles of keratin IF in the regulation of innate immunity and epithelial inflammatory response. While these functions are typically associated with cells of myeloid lineage, epithelial barriers respond to infection or chemical stress by activating primitive innate immunity, primarily but not exclusively, via the NF-kB pathway. The results of this response include partial opening of TJ with loss of barrier function, secretion of anti-bacterial proteins, and recruitment of macrophages and other immune cells via cytokines (reviewed by 93). Keratin-deficient cells and keratin mutations predisposing to inflammation reveal that IF play an important role in the regulation of the epithelial innate immunity responses in the skin and the intestinal epithelial barriers. Some examples are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Examples of effects of keratin loss or keratin mutations on inflammatory mechanisms.

| Affected keratin(s) | Effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| K16 knockout | Regulates innate immunity in response to epithelial barrier opening | 99 |

| R156H K10 overexpression | Activation of p38, secretion of TNFα and RANTES | 109 |

| K17 knockout | Polarizes immune response, Th2 cytokine profile | 145 |

| K5 knockout | Transcriptional upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β | 108 |

| K8 knockout | Th2 chronic intestinal inflammation | 96 |

| K8 / 18 mutations | Intestinal cell barrier function | 98 |

| K8 / 18 knockdown | Activates NF-kB in cancer cells | 142 |

| K10 expression in basal layer of epidermis | Decreased NF-kB activity | 100 |

The paradigm of anti-inflammatory effects of keratins is the K8 knockout mouse. In the C57B1/6 background it is embryonic lethal,16 but partially viable, i.e. submendelian proportions of pups are born in the FVB/N background.94 In these animals, IF are fully abrogated in hepatocytes and the villus epithelium in the small intestine, but present in the crypts because of expression of redundant K7.33,95 Omary and coworkers demonstrated that colitis in the K8-null model displays increased Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13), as well as infiltration of CD4 positive cells in the submucosa. The phenotype amounts to a chronic Th2 colitis induced by a defect in the epithelium and not in immune cells, which lack keratins.96 It is still unclear how intestinal epithelia recruit and activate CD4 positive cells. In these animals, no changes in paracellular permeability were detected in the distal large intestine by Omary and coworkers.97 However, increased 3000 Da Dextran permeability was found in the small intestine,52 suggesting a possible dependence of barrier disruption on the level of the gut. Unfortunately, detailed studies of intestinal permeability at various levels are missing. However, intestinal cells that express K8 or 18 bearing mutations identified in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), showed an impaired barrier function, suggesting an epithelial cell-autonomous mechanism by which TJ permeability is dependent on IF.98 Therefore, increased barrier permeability is a possible mechanism linking deficient keratin expression (or disease associated keratin mutations) and inflammation. Recent evidence from the skin seems to further support this possibility. Genes for K16 or 6, responsible for pachyonychia congenita, appear to display a close coregulation with genes that participate in the regulation of barrier function and innate immunity.99

In terms of transcriptional mechanisms, the K17 null mouse skin shows increased NF-kB activation in response to TNFα. While this can be interpreted as another example of keratin-dependent hyper-sensitivity to TNFα, it shows an indirect control of innate immunity response by specific keratins. K10 expression in the basal layer of the skin is another example of inhibition of NF-kB, possibly through inhibition of IKKβ and IKKγ expression.100 We have recently shown that expression of constitutively active aPKC inhibits NF-kB activity in an epithelial cell line while activating it in a mesenchymal cell line.101 Furthermore, aPKC is downregulated in IBD colon epithelia.102 Bearing in mind that K8 null mice postranslationally downregulate aPKC,52 it is possible that keratin-associated Hsp70 chaperoning also indirectly controls innate immunity activity in epithelia through aPKC. Conversely, it is well-known that inflammation increases keratin expression in pancreas, intestine,95,103,104 and even ectopically, in cells which normally do not express keratins.105

Changes in cytokine expression are also associated with loss of keratin expression or disease-associated keratin mutations.

In skin tumor cells, CXC gene expression levels are controlled by K17 expression.106

In normal keratinocytes, K1 deficiency renders the cells mechanically weaker, but also increases expression of IL-18.107 It is important to note that changes in the transcriptome occur in keratinocytes upon keratin deficiency. More importantly, these changes are specific for different keratins. K1 deficiency mimics the gene expression signature of atopic eczema and psoriasis.107 K5 deficiency displays a different transcriptome signature,107 which results in IL-6 and IL-1β expression.108 Finally, the R156H K10 mutation, causal of a severe form of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, results in increased expression of TNFα and RANTES, and reduced expression of IL-1β.109

While the precise mechanistic relationship between keratin expression (or mutations) and inflammation is still missing, these examples suggest that signaling mechanisms must be involved, and that various keratins may exert their anti-inflammatory effects at the transcriptional level via different pathways. In all known cases, however, there is a common pattern of anti-inflammatory activity of keratins. One may speculate that this is among the evolutionary advantages behind the great redundancy in keratin genes in vertebrates.

Keratins in epithelial polarity

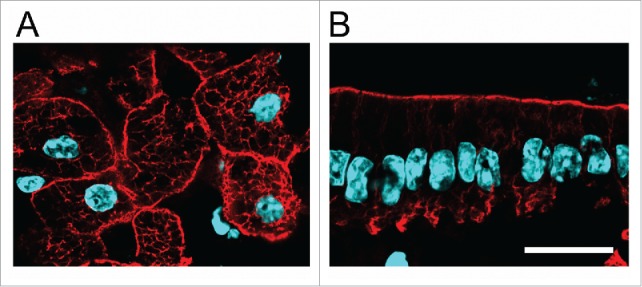

The textbook image of keratin IF normally represents their subcellular distribution in keratinocytes (epidermis). In those cells the filaments fill the cytoplasm and extend from the nucleus to the plasma membrane. A similar non-polarized distribution is found in hepatocytes (Fig. 1A). In most other single-layered (“simple”) epithelia and in epithelial cell lines such as MDCK and Caco-2, however, keratin IF are highly concentrated under the apical domain, showing thin extensions to the lateral domain to connect with desmosomes (reviewed in110). A small basal patch of keratins connects to hemidesmosomes111,112 (Fig. 1B). The mechanism responsible for the subapical concentration of keratin IF remains elusive.

Figure 1.

Polarity of IF in simple epithelia. A, B Frozen sections of formaldehyde-fixed liver (A) and small intestine epithelium (B) stained with anti-K8 antibody (red) and DAPI (light blue). Bar, 20 µm.

The question is whether the asymmetric distribution of keratins plays any role in apico-basal epithelial polarity. Published evidence shows that the formation and early polarization of epithelia in the embryo are not affected by lack of keratins.88,113 This suggests that IF are not involved in the early acquisition of apico-basal polarity. Mistargeting of several polarized membrane proteins, however, was observed in K8 null intestinal epithelia.33,97.Those results indicate the need of keratins for the maintenance of a normal polarized phenotype. Bearing in mind multiple scaffolding functions of keratin IF and the effects on signaling pathways described in the previous sections, understanding the molecular mechanisms that underlie the polarity defects is a challenge.

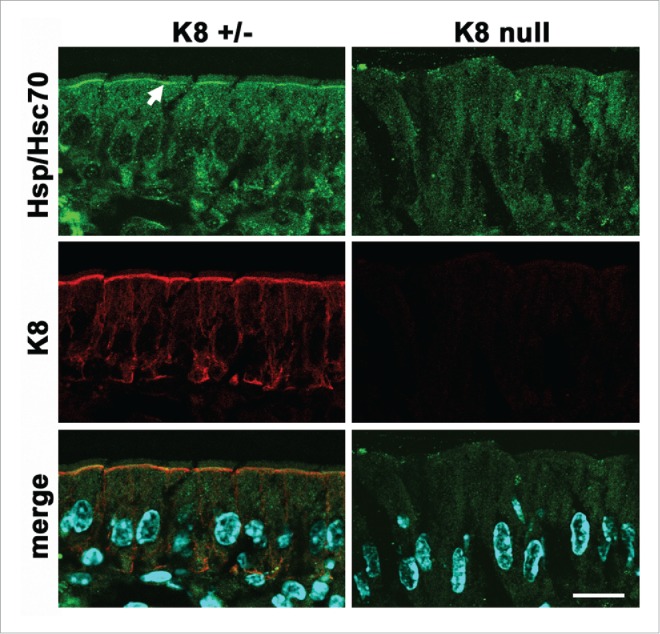

In principle, any of the scaffolding functions of keratin IF described before are expected to be asymmetrically concentrated under the apical domain, and, to some extent at the basal pole (Fig. 1B). As an example, scaffolding of Hsp70 chaperones is strictly dependent on K8 (and IF) expression in villus enterocytes. While there is a diffuse cytoplasmic Hsp70 signal, the chaperone becomes highly concentrated under the apical membrane (Fig. 2, arrow) (additional data in 52). Likewise, it can be speculated that scaffolding of membrane molecules, perhaps through their cytoplasmic domains may control their traffic to the apical domain. Apically-bound membrane traffic vesicles need to cross through the dense layer of apical IF. Annexin II is essential for apical membrane traffic114 and has been found to interact with keratin IF in the context of lipid rafts.115 Another keratin-binding protein is Albatross, which in turn also binds Par3, a component of the polarity complex. Loss of keratins delocalizes Albatross and permits the invasion of basolateral proteins to the apical domain.116

Figure 2.

Polarized scaffolding of Hsp/Hsc70 in simple epithelia. Frozen sections of villus enterocytes from K8-null or heterozygous littermates were immunostained for K8 (red channel) or Hsp/Hsc70 (green channel). The arrow points at the apical concentration of the chaperone which is strictly dependent on the expression of keratin IF. Modified from.52 Bar, 20 µm.

A critically important apical protein, the cystic fibrosis conductance regulator (CFTR) was found to bind K18. Furthermore, the surface expression of CFTR is diminished in K18 null mouse gallbladder and duodenum117 and in K8 null intestinal epithelia.33 This suggests that membrane traffic can be positively regulated by keratins. Conversely, the glucose transporters GLUT1 and −3 are mislocalized away from the apical domain of keratin-null embryonic epithelia,113 which deprives the cells of energy and activates AMPK, thus decreasing protein synthesis through mTOR inhibition. It is of note that the LKB1/AMPK pathway has been shown to control bile canaliculus (apical) formation in hepatocytes 118 as well. As mentioned before, another signaling mechanism, atypical PKC, is downregulated in K8 null epithelia, thus providing a possible explanation for both increased permeability of TJ and protein mistargeting. Furthermore, aPKC is also known to control surface localization of various glucose transporters in non-epithelial cells, including GLUT1.119,120 While this function has not been demonstrated in epithelial cells, it remains a possible explanation for the results of Magin and coworkers in embryonic epithelia.113

Additionally, somewhat indirect mechanisms may also explain changes in apical polarity in keratin null phenotypes. Expression of plastin 1 (fimbrin), a keratin-binding protein, is necessary to maintain the structure of the apical terminal web, which comprises the highly-concentrated apical keratin IF.121

The distribution of apical microtubules is severely affected by the K8-null mutation, possibly through mislocalization of gamma-tubulin ring complexes.122 In addition, activation of pro-inflammatory signaling may also play a role. In fact, apical mistargeting in K8-null colonocytes is partially reverted by treatment with antibiotics, which decreases the inflammatory response.96 Although no data is currently available in the intestinal epithelium regarding innate immunity signaling in K8 null mice, in breast cancer cells in 3D cultures, inhibition of NF-kB by small molecules or shRNA induces apico-basal polarization.123 Finally, the role of inflammation in the integrity of TJ has been reviewed elsewhere.124 At least one polarity protein, Scribble, is delocalized under pro-inflammatory signals.125 Accordingly, a relationship between innate immunity pathways and epithelial apico-basal polarity in the context of keratin deficient cells is worth further studies.

Challenges ahead to elucidate mechanistic aspects of IF function

The major challenge of IF research is that multiple functions, mechanical and non-mechanical, are affected simultaneously. Establishing a simple linear cause-effect relationship is, therefore, very difficult. The network of functions regulated by IF, in addition, may vary in different cell types. Loss of keratin expression or expression of keratin mutants associated with human disease results in increased sensitivity to apoptosis (in liver, placenta, and skin), changes in key signaling pathways, pro-inflammatory phenotype and partial loss of apico-basal polarity (intestine). Questions that remain unanswered, such as the examples that follow, are related to molecular mechanisms, cross-talk among them, and tissue specificity. How do IF protect epithelial cells from chemical stress, diminish innate immunity responses, and favor appropriate segregation of apical membrane proteins? The gaps of knowledge in this field are precisely at the interface between keratin molecules and interacting proteins involved in a substantial number of molecular mechanisms perturbed by loss of keratin function. Why do IF protect hepatocytes but not villus enterocytes from apoptosis? In both cases the loss of IF in the K8 null model is complete. There is no question that keratin IF contribute to the mechanical “stiffness” of epithelial cells,90 but it is difficult to conceive that a hepatocyte may have harsher mechanical stresses than a small intestine villus enterocyte. That is especially true considering the fiber-rich diet of a rodent. Conversely, in the skin, at least one mutation (E477D K5p) does not impair mechanical characteristics of keratinocytes and yet causes EBS.25

The most obvious alternative to effects of cellular mechanical weakness is the scaffolding of several molecules which control intracellular signaling. From an evolutionary standpoint, this option makes sense to explain the formidable redundancy in type I and type II keratin genes developed during the evolution of chordates. Only one type I and one type II keratin gene would suffice to assemble filaments, as, for example, in early chordates.126 However, many different keratin head and tail domains would be necessary to accommodate tissue-specific scaffolding in vertebrates.

Binding to keratin IF, however, is not an all or none phenomenon. Quantitative evaluation of scaffolding, (i.e., how much of the protein is bound to filaments and how much is free) is still needed in many cases. Likewise, quantification of the effects of scaffolding (i.e. how much protein bound to filaments is necessary to result in a certain change in a cell function) will be necessary to determine the impact of immobilization of cellular components on IF. This is especially important because keratin loss of function seems to affect multiple mechanisms. Accordingly it will be necessary to assess the relative importance of each one. While the current trend is to analyze effects at the cellular or animal level, there is a need for subcellular quantitative analysis as well, for example, separating keratin IF from the cytosol to measure function of the same molecules on the filament surface as opposed to the non-filamentous environment.127 Ultimately, the interaction domains in keratins and each keratin binding protein will need to be determined. Molecular analysis at that level will confirm the conclusions from knockout models. In addition, it is conceivable that some interactions may be indirect. We can speculate that there is potential therapeutic significance in understanding mechanistically the interactions between keratins and signaling molecules. These interactions are expected to be specific to epithelia. In the same line of thought, because carcinomas still express keratins, it is likely that some of the keratin functions may still constitute a therapeutic target in cancer. For example, knockout of K14 in breast cancer cells abrogates invasiveness.128 Understanding how K14 controls a differentiation program may help prevent metastasis. The implications for human health of understanding how keratins protect epithelia, therefore, may go beyond the numerous diseases caused or predisposed by keratin mutations.129,130

Abbreviations

- Akt

Protein kinase B

- aPKC

Atypical protein kinase C (isoforms ι/λ and νδ ζ)

- Bag

BCL2-associated athanogene

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DEDD

Death Effector Domain Containing protein

- EBS

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex

- ERK

Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinase

- Hsp

Heat shock protein

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IF

intermediate filament

- IKK

inhibitor of kappa B kinase

- IL

Interleukin

- K

keratin protein

- Krt

keratin gene

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NF-Kb

Nuclear factor kappa β

- Par

PARtition deficient mutations in C. elegans. Homolog proteins in vertebrates

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- Rack

receptor for activated C-kinase

- ROCK

Rho-associated protein kinase

- TJ

tight junction

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- TNFR

TNF receptor

- TRADD

TNFR-associated death domain protein

- ZO-1

Zonula occludens 1 protein, a tight junction structural component

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgment

The authors are thankful to Dr. Robert Warren for editing and critical reviewing of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grant R01-DK076652 to PJS and a grant from Nova Southeastern University to AM. RF was a recipient of NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Fellowship (F32-DK095503).

References

- [1].Tyler S. Epithelium–the primary building block for metazoan complexity. Integr Comp Biol 2003; 43:55-63; PMID:21680409; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/icb/43.1.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fahey B, Degnan BM. Origin of animal epithelia: insights from the sponge genome. Evol Dev 2010; 12:601-17; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2010.00445.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Salinas-Saavedra M, Stephenson TQ, Dunn CW, Martindale MQ. Par system components are asymmetrically localized in ectodermal epithelia, but not during early development in the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. Evodevo 2015; 6:20; PMID:26101582; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/s13227-015-0014-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ganot P, Zoccola D, Tambutte E, Voolstra CR, Aranda M, Allemand D, Tambutté S. Structural molecular components of septate junctions in cnidarians point to the origin of epithelial junctions in eukaryotes. Mol Biol Evol 2015; 32:44-62; PMID:25246700; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/molbev/msu265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Eriksson JE, Dechat T, Grin B, Helfand B, Mendez M, Pallari HM, Goldman RD. Introducing intermediate filaments: from discovery to disease. J Clin Invest 2009; 119:1763-71; PMID:19587451; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI38339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Blumenberg M. Evolution of homologous domains of cytoplasmic intermediate filament proteins and lamins. Mol Biol Evol 1989; 6:53-65; PMID:2921943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pieczynski J, Margolis B. Protein complexes that control renal epithelial polarity. Am J Physiol Renal Phys 2011; 300:F589-601; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajprenal.00615.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Guo S, Kemphues KJ. Molecular genetics of asymmetric cleavage in the early Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1996; 6:408-15; PMID:8791533; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0959-437X(96)80061-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gilmore TD, Wolenski FS. NF-kappaB: where did it come from and why? Immun Rev 2012; 246:14-35; PMID:22435545; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01096.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schweizer J, Bowden PE, Coulombe PA, Langbein L, Lane EB, Magin TM, Maltais L, Omary MB, Parry DA, Rogers MA, et al.. New consensus nomenclature for mammalian keratins. Journal Cell Biol 2006; 174:169-74; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200603161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Moll R, Divo M, Langbein L. The human keratins: biology and pathology. Histochem Cell Biol 2008; 129:705-33; PMID:18461349; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00418-008-0435-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Moll R, Franke WW, Schiller DL, Geiger B, Krepler R. The catalog of human cytokeratins: patterns of expression in normal epithelia, tumors and cultured cells. Cell 1982; 31:11-24; PMID:6186379; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90400-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Snider NT, Omary MB. Post-translational modifications of intermediate filament proteins: mechanisms and functions. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014; 15:163-77; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm3753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Grin B, Mahammad S, Wedig T, Cleland MM, Tsai L, Herrmann H, Goldman RD. Withaferin a alters intermediate filament organization, cell shape and behavior. PloS One 2012; 7:e39065; PMID:22720028; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0039065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sun J, Groppi VE, Gui H, Chen L, Xie Q, Liu L, Omary MB. High-Throughput Screening for Drugs that Modulate Intermediate Filament Proteins. Methods Enzymol 2016; 568:163-85; PMID:26795471; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.09.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Baribault H, Price J, Miyai K, Oshima RG. Mid-gestational lethality in mice lacking keratin 8. Genes Develop 1993; 7:1191-202; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bar J, Kumar V, Roth W, Schwarz N, Richter M, Leube RE, Magin TM. Skin fragility and impaired desmosomal adhesion in mice lacking all keratins. J Invest Dermatol 2014; 134:1012-22; PMID:24121403; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/jid.2013.416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sandilands A, Smith FJ, Lunny DP, Campbell LE, Davidson KM, MacCallum SF, Corden LD, Christie L, Fleming S, Lane EB, et al.. Generation and characterisation of keratin 7 (K7) knockout mice. PloS One 2013; 8:e64404; PMID:23741325; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0064404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Koster S, Weitz DA, Goldman RD, Aebi U, Herrmann H. Intermediate filament mechanics in vitro and in the cell: from coiled coils to filaments, fibers and networks. Curr Opinion Cell Biol 2015; 32c:82-91; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Coulombe PA, Lee CH. Defining keratin protein function in skin epithelia: epidermolysis bullosa simplex and its aftermath. J Invest Dermatol 2012; 132:763-75; PMID:22277943; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/jid.2011.450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bolling MC, Jongbloed JD, Boven LG, Diercks GF, Smith FJ, McLean WH, Jonkman MF. Plectin mutations underlie epidermolysis bullosa simplex in 8% of patients. J Invest Dermatol 2014; 134:273-6; PMID:23774525; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/jid.2013.277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wagner M, Trost A, Hintner H, Bauer JW, Onder K. Imbalance of intermediate filament component keratin 14 contributes to increased stress signalling in epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Experiment Dermatol 2013; 22:292-4; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/exd.12112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yoneda K, Furukawa T, Zheng YJ, Momoi T, Izawa I, Inagaki M, Manabe M, Inagaki N. An autocrine/paracrine loop linking keratin 14 aggregates to tumor necrosis factor α-mediated cytotoxicity in a keratinocyte model of epidermolysis bullosa simplex. J Biol Chem 2004; 279:7296-303; PMID:14660619; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M307242200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].El-HawarSy MS, Abdel-Halim MR, Sayed SS, Abdelkader HA. Apocytolysis, a proposed mechanism of blister formation in epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Arch Dermatol Res 2015; 307:371-7; PMID:25822146; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00403-015-1560-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Homberg M, Ramms L, Schwarz N, Dreissen G, Leube RE, Merkel R, Hoffmann B, Magin TM. Distinct Impact of Two Keratin Mutations Causing Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex on Keratinocyte Adhesion and Stiffness. J Invest Dermatol 2015; 135:2437-45; PMID:25961909; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/jid.2015.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bordeleau F, Myrand Lapierre ME, Sheng Y, Marceau N. Keratin 8/18 regulation of cell stiffness-extracellular matrix interplay through modulation of Rho-mediated actin cytoskeleton dynamics. PloS One 2012; 7:e38780; PMID:22685604; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0038780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Caulin C, Ware CF, Magin TM, Oshima RG. Keratin-dependent, epithelial resistance to tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol 2000; 149:17-22; PMID:10747083; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.149.1.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jaquemar D, Kupriyanov S, Wankell M, Avis J, Benirschke K, Baribault H, Oshima RG. Keratin 8 protection of placental barrier function. J Cell Biol 2003; 161:749-56; PMID:12771125; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200210004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Leifeld L, Kothe S, Sohl G, Hesse M, Sauerbruch T, Magin TM, Spengler U. Keratin 18 provides resistance to Fas-mediated liver failure in mice. Europ J Clin Invest 2009; 39:481-8; PMID:19397691; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02133.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].McGowan KM, Tong X, Colucci-Guyon E, Langa F, Babinet C, Coulombe PA. Keratin 17 null mice exhibit age- and strain-dependent alopecia. Genes Dev 2002; 16:1412-22; PMID:12050118; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.979502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tong X, Coulombe PA. Keratin 17 modulates hair follicle cycling in a TNFalpha-dependent fashion. Genes Develop 2006; 20:1353-64; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1387406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lugassy J, McGrath JA, Itin P, Shemer R, Verbov J, Murphy HR, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Digiovanna JJ, Bercovich D, Karin N, et al.. KRT14 haploinsufficiency results in increased susceptibility of keratinocytes to TNF-α-induced apoptosis and causes Naegeli-Franceschetti-Jadassohn syndrome. J Invest Dermatol 2008; 128:1517-24; PMID:18049449; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.jid.5701187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ameen NA, Figueroa Y, Salas PJ. Anomalous apical plasma membrane phenotype in CK8-deficient mice indicates a novel role for intermediate filaments in the polarization of simple epithelia. J Cell Sci 2001; 114:563-75; PMID:11171325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Habtezion A, Toivola DM, Asghar MN, Kronmal GS, Brooks JD, Butcher EC, Omary MB. Absence of keratin 8 confers a paradoxical microflora-dependent resistance to apoptosis in the colon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108:1445-50; PMID:21220329; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1010833108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ku NO, Soetikno RM, Omary MB. Keratin mutation in transgenic mice predisposes to Fas but not TNF-induced apoptosis and massive liver injury. Hepatology 2003; 37:1006-14; PMID:12717381; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1053/jhep.2003.50181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Chen J, Cheng X, Merched-Sauvage M, Caulin C, Roop DR, Koch PJ. An unexpected role for keratin 10 end domains in susceptibility to skin cancer. J Cell Sci 2006; 119:5067-76; PMID:17118961; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.03298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Usachov V, Urban TJ, Fontana RJ, Gross A, Iyer S, Omary MB, Strnad P. Prevalence of genetic variants of keratins 8 and 18 in patients with drug-induced liver injury. BMC Med 2015; 13:196; PMID:26286715; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/s12916-015-0418-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Strnad P, Zhou Q, Hanada S, Lazzeroni LC, Zhong BH, So P, Davern TJ, Lee WM. Keratin variants predispose to acute liver failure and adverse outcome: race and ethnic associations. Gastroenterol 2010; 139:828-35; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhong B, Strnad P, Selmi C, Invernizzi P, Tao GZ, Caleffi A, Chen M, Bianchi I, Podda M, Pietrangelo A, et al.. Keratin variants are overrepresented in primary biliary cirrhosis and associate with disease severity. Hepatol 2009; 50:546-54; PMID:19585610; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/hep.23041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Inada H, Izawa I, Nishizawa M, Fujita E, Kiyono T, Takahashi T, Momoi T, Inagaki M. Keratin attenuates tumor necrosis factor-induced cytotoxicity through association with TRADD. J Cell Biol 2001; 155:415-26; PMID:11684708; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200103078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gilbert S, Loranger A, Marceau N. Keratins modulate c-Flip/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 antiapoptotic signaling in simple epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24:7072-81; PMID:15282307; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.24.16.7072-7081.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Schutte B, Henfling M, Ramaekers FC. DEDD association with cytokeratin filaments correlates with sensitivity to apoptosis. Apoptosis 2006; 11:1561-72; PMID:16820959; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10495-006-9113-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lin YM, Chen YR, Lin JR, Wang WJ, Inoko A, Inagaki M, Wu YC, Chen RH. eIF3k regulates apoptosis in epithelial cells by releasing caspase 3 from keratin-containing inclusions. J Cell Sci 2008; 121:2382-93; PMID:18577580; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.021394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Duan S, Yao Z, Zhu Y, Wang G, Hou D, Wen L, Wu M. The Pirh2-keratin 8/18 interaction modulates the cellular distribution of mitochondria and UV-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Diff 2009; 16:826-37; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cdd.2009.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Bordeleau F, Galarneau L, Gilbert S, Loranger A, Marceau N. Keratin 8/18 modulation of protein kinase C-mediated integrin-dependent adhesion and migration of liver epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 2010; 21:1698-713; PMID:20357007; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E09-05-0373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Izawa I, Nishizawa M, Ohtakara K, Ohtsuka K, Inada H, Inagaki M. Identification of Mrj, a DnaJ/Hsp40 family protein, as a keratin 8/18 filament regulatory protein. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:34521-7; PMID:10954706; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M003492200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Perng MD, Cairns L, van den IP, Prescott A, Hutcheson AM, Quinlan RA. Intermediate filament interactions can be altered by HSP27 and alphaB-crystallin. J Cell Sci 1999; 112(Pt 13):2099-112; PMID:10362540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Liao J, Lowthert LA, Ghori N, Omary MB. The 70-kDa heat shock proteins associate with glandular intermediate filaments in an ATP-dependent manner. J Biol Chem 1995; 270:915-22; PMID:7529764; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.270.2.915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Gu LH, Coulombe PA. Defining the properties of the nonhelical tail domain in type II keratin 5: insight from a bullous disease-causing mutation. Mol Biol Cell 2005; 16:1427-38; PMID:15647384; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wiche G, Osmanagic-Myers S, Castanon MJ. Networking and anchoring through plectin: a key to IF functionality and mechanotransduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2015; 32:21-9; PMID:25460778; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Nekrasova O, Green KJ. Desmosome assembly and dynamics. Trends Cell Biol 2013; 23:537-46; PMID:23891292; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Mashukova A, Oriolo AS, Wald FA, Casanova ML, Kroger C, Magin TM, Omary MB, Salas PJ. Rescue of atypical protein kinase C in epithelia by the cytoskeleton and Hsp70 family chaperones. J Cell Sci 2009; 122:2491-503; PMID:19549684; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.046979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Mashukova A, Kozhekbaeva Z, Forteza R, Dulam V, Figueroa Y, Warren R, Salas PJ. The BAG-1 isoform BAG-1M regulates keratin-associated Hsp70 chaperoning of aPKC in intestinal cells during activation of inflammatory signaling. J Cell Sci 2014; 127:3568-77; PMID:24876225; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.151084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Quinlan RA, Carte JM, Sandilands A, Prescott AR. The beaded filament of the eye lens: an unexpected key to intermediate filament structure and function. Trends in Cell Biol 1996; 6:123-6; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0962-8924(96)20001-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Chen L, Wang Y, Zhao L, Chen W, Dong C, Zhao X, Li X. Hsp74, a potential bladder cancer marker, has direct interaction with keratin 1. J Immunol Res 2014; 2014:492849; PMID:25050384; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1155/2014/492849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kayser J, Haslbeck M, Dempfle L, Krause M, Grashoff C, Buchner J, Herrmann H, Bausch AR. The small heat shock protein Hsp27 affects assembly dynamics and structure of keratin intermediate filament networks. Biophys J 2013; 105:1778-85; PMID:24138853; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Gao T, Newton AC. Invariant Leu preceding turn motif phosphorylation site controls the interaction of protein kinase C with Hsp70. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:32461-8; PMID:16954220; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M604076200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Gould CM, Newton AC. The life and death of protein kinase C. Curr Drug Targets 2008; 9:614-25; PMID:18691009; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/138945008785132411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Mashukova A, Forteza R, Wald FA, Salas PJ. PDK1 in apical signaling endosomes participates in the rescue of the polarity complex atypical PKC by intermediate filaments in intestinal epithelia. Mol Biol Cell 2012; 23:1664-74; PMID:22398726; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-0988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Yamazaki S, Uchiumi A, Katagata Y. Hsp40 regulates the amount of keratin proteins via ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in cultured human cells. Int J Mol Med 2012; 29:165-8; PMID:22075554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Loffek S, Woll S, Hohfeld J, Leube RE, Has C, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Magin TM. The ubiquitin ligase CHIP/STUB1 targets mutant keratins for degradation. Hum Mutation 2010; 31:466-76; PMID:20151404; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/humu.21222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Watson ED, Geary-Joo C, Hughes M, Cross JC. The Mrj co-chaperone mediates keratin turnover and prevents the formation of toxic inclusion bodies in trophoblast cells of the placenta. Develop 2007; 134:1809-17; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.02843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zatloukal K, Stumptner C, Fuchsbichler A, Heid H, Schnoelzer M, Kenner L, Kleinert R, Prinz M, Aguzzi A, Denk H. p62 Is a common component of cytoplasmic inclusions in protein aggregation diseases. Am J Pathol 2002; 160:255-63; PMID:11786419; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64369-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Wald FA, Oriolo AS, Casanova ML, Salas PJ. Intermediate filaments interact with dormant ezrin in intestinal epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 2005; 16:4096-107; PMID:15987737; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Lu R, Dalgalan D, Mandell EK, Parker SS, Ghosh S, Wilson JM. PKCiota interacts with Rab14 and modulates epithelial barrier function through regulation of claudin-2 levels. Mol Biol Cell 2015; 26:1523-31; PMID:25694446; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E14-12-1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Iden S, Misselwitz S, Peddibhotla SS, Tuncay H, Rehder D, Gerke V, Robenek H, Suzuki A, Ebnet K. aPKC phosphorylates JAM-A at Ser285 to promote cell contact maturation and tight junction formation. J Cell Biol 2012; 196:623-39; PMID:22371556; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201104143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Helfrich I, Schmitz A, Zigrino P, Michels C, Haase I, le Bivic A, Leitges M, Niessen CM. Role of aPKC isoforms and their binding partners Par3 and Par6 in epidermal barrier formation. J Invest Dermatol 2007; 127:782-91; PMID:17110935; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.jid.5700621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Kim B, Breton S. The MAPK/ERK-Signaling Pathway Regulates the Expression and Distribution of Tight Junction Proteins in the Mouse Proximal Epididymis. Biol Reprod 2015; 94(1):22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Elsum IA, Martin C, Humbert PO. Scribble regulates an EMT polarity pathway through modulation of MAPK-ERK signaling to mediate junction formation. J Cell Sci 2013; 126:3990-9; PMID:23813956; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.129387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Lei S, Cheng T, Guo Y, Li C, Zhang W, Zhi F. Somatostatin ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced tight junction damage via the ERK-MAPK pathway in Caco2 cells. Eur J Cell Biol 2014; 93:299-307; PMID:24950815; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ejcb.2014.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Tanos BE, Perez Bay AE, Salvarezza S, Vivanco I, Mellinghoff I, Osman M, Sacks DB, Rodriguez-Boulan E. IQGAP1 controls tight junction formation through differential regulation of claudin recruitment. J Cell Sci 2015; 128:853-62; PMID:25588839; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.118703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Minakami M, Kitagawa N, Iida H, Anan H, Inai T. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase regulate the accumulation of a tight junction protein, ZO-1, in cell-cell contacts in HaCaT cells. Tissue Cell 2015; 47:1-9; PMID:25435485; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tice.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].DiTommaso T, Cottle DL, Pearson HB, Schluter H, Kaur P, Humbert PO, Smyth IM. Keratin 76 is required for tight junction function and maintenance of the skin barrier. PLoS Genet 2014; 10:e1004706; PMID:25340345; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Babula JJ, Liu JY. Integrate Omics Data and Molecular Dynamics Simulations toward Better Understanding of Human 14-3-3 Interactomes and Better Drugs for Cancer Therapy. J Genet Genomics 2015; 42:531-47; PMID: 26554908; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jgg.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Ku NO, Michie S, Resurreccion EZ, Broome RL, Omary MB. Keratin binding to 14-3-3 proteins modulates keratin filaments and hepatocyte mitotic progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002; 99:4373-8; PMID:11917136; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.072624299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Satoh J, Nanri Y, Yamamura T. Rapid identification of 14-3-3-binding proteins by protein microarray analysis. J Neurosci Methods 2006; 152:278-88; PMID:16260042; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Kim S, Wong P, Coulombe PA. A keratin cytoskeletal protein regulates protein synthesis and epithelial cell growth. Nature 2006; 441:362-5; PMID:16710422; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature04659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Liffers ST, Maghnouj A, Munding JB, Jackstadt R, Herbrand U, Schulenborg T, Marcus K, Klein-Scory S, Schmiegel W, Schwarte-Waldhoff I, et al.. Keratin 23, a novel DPC4/Smad4 target gene which binds 14-3-3epsilon. BMC Cancer 2011; 11:137; PMID:21492476; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2407-11-137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Obsil T, Obsilova V. Structural basis of 14-3-3 protein functions. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2011; 22:663-72; PMID:21920446; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Ku NO, Fu H, Omary MB. Raf-1 activation disrupts its binding to keratins during cell stress. J Cell Biol 2004; 166:479-85; PMID:15314064; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200402051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Yano S, Komine M, Fujimoto M, Okochi H, Tamaki K. Mechanical stretching in vitro regulates signal transduction pathways and cellular proliferation in human epidermal keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2004; 122:783-90; PMID:15086566; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Wang J, Zhang Y, Zhang N, Wang C, Herrler T, Li Q. An updated review of mechanotransduction in skin disorders: transcriptional regulators, ion channels, and microRNAs. Cell Mol Life Sci 2015; 72:2091-106; PMID:25681865; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-015-1853-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Sivaramakrishnan S, Schneider JL, Sitikov A, Goldman RD, Ridge KM. Shear stress induced reorganization of the keratin intermediate filament network requires phosphorylation by protein kinase C zeta. Mol Biol Cell 2009; 20:2755-65; PMID:19357195; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Walko G, Castanon MJ, Wiche G. Molecular architecture and function of the hemidesmosome. Cell Tissue Res 2015; 360:529-44; PMID:26017636; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00441-015-2216-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Hammers CM, Stanley JR. Mechanisms of Disease: Pemphigus and Bullous Pemphigoid. Annu Rev Pathol 2016; PMID:26907530; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012615-044313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Nitoiu D, Etheridge SL, Kelsell DP. Insights into desmosome biology from inherited human skin disease and cardiocutaneous syndromes. Cell Commun Adhes 2014; 21:129-40; PMID:24738885; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3109/15419061.2014.908854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Koss-Harnes D, Hoyheim B, Anton-Lamprecht I, Gjesti A, Jorgensen RS, Jahnsen FL, Olaisen B, Wiche G, Gedde-Dahl T Jr. A site-specific plectin mutation causes dominant epidermolysis bullosa simplex Ogna: two identical de novo mutations. J Invest Dermatol 2002; 118:87-93; PMID:11851880; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01591.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Baribault H, Oshima RG. Polarized and functional epithelia can form after the targeted inactivation of both mouse keratin 8 alleles. J Cell Biol 1991; 115:1675-84; PMID:1721911; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.115.6.1675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Magin TM, Schroder R, Leitgeb S, Wanninger F, Zatloukal K, Grund C, Melton DW. Lessons from keratin 18 knockout mice: formation of novel keratin filaments, secondary loss of keratin 7 and accumulation of liver-specific keratin 8-positive aggregates. J Cell Biol 1998; 140:1441-51; PMID:9508776; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Seltmann K, Fritsch AW, Kas JA, Magin TM. Keratins significantly contribute to cell stiffness and impact invasive behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110:18507-12; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1310493110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Wallace L, Roberts-Thompson L, Reichelt J. Deletion of K1/K10 does not impair epidermal stratification but affects desmosomal structure and nuclear integrity. J Cell Sci 2012; 125:1750-8; PMID:22375063; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.097139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Loschke F, Homberg M, Magin TM. Keratin Isotypes Control Desmosome Stability and Dynamics through PKCalpha. J Invest Dermatol 2016; 136:202-13; PMID:26763440; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/JID.2015.403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Koch S, Nusrat A. The life and death of epithelia during inflammation: lessons learned from the gut. Annu Rev Pathol 2012; 7:35-60; PMID:21838548; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-120905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Baribault H, Penner J, Iozzo RV, Wilson-Heiner M. Colorectal hyperplasia and inflammation in keratin 8-deficient FVB/N mice. Genes Dev 1994; 8:2964-73; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.8.24.2964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Asghar MN, Silvander JS, Helenius TO, Lahdeniemi IA, Alam C, Fortelius LE, Holmsten RO, Toivola DM. The amount of keratins matters for stress protection of the colonic epithelium. PloS One 2015; 10:e0127436; PMID:26000979; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0127436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Habtezion A, Toivola DM, Butcher EC, Omary MB. Keratin-8-deficient mice develop chronic spontaneous Th2 colitis amenable to antibiotic treatment. J Cell Sci 2005; 118:1971-80; PMID:15840656; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.02316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Toivola DM, Krishnan S, Binder HJ, Singh SK, Omary MB. Keratins modulate colonocyte electrolyte transport via protein mistargeting. J Cell Biol 2004; 164:911-21; PMID:15007064; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200308103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Zupancic T, Stojan J, Lane EB, Komel R, Bedina-Zavec A, Liovic M. Intestinal cell barrier function in vitro is severely compromised by keratin 8 and 18 mutations identified in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. PloS One 2014; 9:e99398; PMID:24915158; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0099398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Lessard JC, Pina-Paz S, Rotty JD, Hickerson RP, Kaspar RL, Balmain A, Coulombe PA. Keratin 16 regulates innate immunity in response to epidermal barrier breach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110:19537-42; PMID:24218583; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1309576110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Santos M, Perez P, Segrelles C, Ruiz S, Jorcano JL, Paramio JM. Impaired NF-kappa B activation and increased production of tumor necrosis factor α in transgenic mice expressing keratin K10 in the basal layer of the epidermis. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:13422-30; PMID:12566451; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M208170200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Forteza R, Wald FA, Mashukova A, Kozhekbaeva Z, Salas PJ. Par-complex aPKC and Par3 cross-talk with innate immunity NF-kappaB pathway in epithelial cells. Biol Open 2013; 2:1264-9; PMID:24244864; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/bio.20135918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Wald FA, Forteza R, Diwadkar-Watkins R, Mashukova A, Duncan R, Abreu MT, Salas PJ. Aberrant expression of the polarity complex atypical PKC and non-muscle myosin IIA in active and inactive inflammatory bowel disease. Virch Arch 2011; 459:331-8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00428-011-1102-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Zhong B, Zhou Q, Toivola DM, Tao GZ, Resurreccion EZ, Omary MB. Organ-specific stress induces mouse pancreatic keratin overexpression in association with NF-kappaB activation. J Cell Sci 2004; 117:1709-19; PMID:15075232; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.01016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Corfe BM, Majumdar D, Assadsangabi A, Marsh AM, Cross SS, Connolly JB, Evans CA, Lobo AJ. Inflammation decreases keratin level in ulcerative colitis; inadequate restoration associates with increased risk of colitis-associated cancer. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2015; 2:e000024; PMID:26462276; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/bmjgast-2014-000024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Papathanasiou S, Rickelt S, Soriano ME, Schips TG, Maier HJ, Davos CH, Varela A, Kaklamanis L, Mann DL, Capetanaki Y. Tumor necrosis factor-α confers cardioprotection through ectopic expression of keratins K8 and K18. Nat Med 2015; 21:1076-84; PMID:26280121; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.3925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Hobbs RP, DePianto DJ, Jacob JT, Han MC, Chung BM, Batazzi AS, Poll BG, Guo Y, Han J, Ong S, et al.. Keratin-dependent regulation of Aire and gene expression in skin tumor keratinocytes. Nat Genet 2015; 47:933-8; PMID:26168014; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng.3355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Roth W, Kumar V, Beer HD, Richter M, Wohlenberg C, Reuter U, Thiering S, Staratschek-Jox A, Hofmann A, Kreusch F, et al.. Keratin 1 maintains skin integrity and participates in an inflammatory network in skin through interleukin-18. J Cell Sci 2012; 125:5269-79; PMID:23132931; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.116574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Lu H, Chen J, Planko L, Zigrino P, Klein-Hitpass L, Magin TM. Induction of inflammatory cytokines by a keratin mutation and their repression by a small molecule in a mouse model for EBS. J Invest Dermatol 2007; 127:2781-9; PMID:17581617; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.jid.5700918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Obarzanek-Fojt M, Favre B, Huber M, Ryser S, Moodycliffe AM, Wipff PJ, Hinz B, Hohl D. Induction of p38, tumour necrosis factor-α and RANTES by mechanical stretching of keratinocytes expressing mutant keratin 10R156H. Br J Dermatol 2011; 164:125-34; PMID:20804491; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10013.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Oriolo AS, Wald FA, Ramsauer VP, Salas PJ. Intermediate filaments: a role in epithelial polarity. Exp Cell Res 2007; 313:2255-64; PMID:17425955; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.02.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Stutzmann J, Bellissent-Waydelich A, Fontao L, Launay JF, Simon-Assmann P. Adhesion complexes implicated in intestinal epithelial cell-matrix interactions. Microsc Res Tech 2000; 51:179-90; PMID:11054868; http://dx.doi.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Seltmann K, Cheng F, Wiche G, Eriksson JE, Magin TM. Keratins Stabilize Hemidesmosomes Through Regulation of beta4-Integrin Turnover. J Invest Dermatol 2015; 135(6):1609-20; PMID:25668239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Vijayaraj P, Kroger C, Reuter U, Windoffer R, Leube RE, Magin TM. Keratins regulate protein biosynthesis through localization of GLUT1 and −3 upstream of AMP kinase and Raptor. J Cell Biol 2009; 187:175-84; PMID:19841136; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200906094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Bryant DM, Datta A, Rodriguez-Fraticelli AE, Peranen J, Martin-Belmonte F, Mostov KE. A molecular network for de novo generation of the apical surface and lumen. Nat Cell Biol 2010; 12:1035-45; PMID:20890297; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Hein Z, Schmidt S, Zimmer KP, Naim HY. The dual role of annexin II in targeting of brush border proteins and in intestinal cell polarity. Differentiation Res Biol Diversity 2011; 81:243-52; PMID:21330046; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.diff.2011.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Sugimoto M, Inoko A, Shiromizu T, Nakayama M, Zou P, Yonemura S, Hayashi Y, Izawa I, Sasoh M, Uji Y, et al.. The keratin-binding protein Albatross regulates polarization of epithelial cells. J Cell Biol 2008; 183:19-28; PMID:18838552; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200803133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Duan Y, Sun Y, Zhang F, Zhang WK, Wang D, Wang Y, Cao X, Hu W, Xie C, Cuppoletti J, et al.. Keratin K18 increases cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) surface expression by binding to its C-terminal hydrophobic patch. J Biol Chem 2012; 287:40547-59; PMID:23045527; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M112.403584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Homolya L, Fu D, Sengupta P, Jarnik M, Gillet JP, Vitale-Cross L, Gutkind JS, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Arias IM. LKB1/AMPK and PKA control ABCB11 trafficking and polarization in hepatocytes. PloS One 2014; 9:e91921; PMID:24643070; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0091921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]