Abstract

Objective

To assess whether variation in serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) measures, used to assess early gestation viability, are associated with differences in clinical presentation and patient factors.

Method

This retrospective cohort study included 285 women with first-trimester pain and bleeding and a pregnancy of unknown location, for whom a normal intrauterine pregnancy was ultimately confirmed. Serial samples were collected at three U.S. sites and hCG changes were analyzed for differences by race, ethnicity and clinical factors. A nonlinear, mixed effects regression model was used assuming a random subject shift in the time axis.

Results

The hCG rise in symptomatic women with ongoing intrauterine pregnancy differs by patient factors, and level at presentation. The 2-day minimum (1st percentile) rise in hCG was faster when presenting hCG values were low and slower when presenting hCG value was high. African American had a faster hCG rise (p <0.001) compared to non-African American women. Variation in hCG curves was associated with prior miscarriage (p=0.014), presentation bleeding (p<0.001), and pain (p=0.002). For initial hCG values of <1500, 1500–3000 and >3000 mIU/mL, the predicted 2- day minimal (1st percentile) rise was 49%, 40% and 33%, respectively.

Conclusion

The rise of hCG levels in women with a viable intrauterine pregnancy and symptoms of potential pregnancy failure varies significantly by initial value. Changes in hCG rise related to race should not affect clinical care. In order to limit interruption of a potential desired IUP, a more conservative “cut off “(slower rise) is needed when hCG values are high.

Clinical Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00194168.

INTRODUCTION

For women in early pregnancy with symptoms of abdominal pain, with or without vaginal bleeding, ultrasound can diagnose intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) in 70–90% of cases. However, in 10–30% of cases (1–2) where ultrasound cannot definitively diagnose an ongoing pregnancy, miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy, diagnosis is difficult when the presenting hCG is below the discriminatory zone (<2000–3000 mIU/mL) (3–7). Incorrect diagnosis in these patients has a heavy ‘cost’ of interruption of a desired viable IUP or rupture of an ectopic pregnancy.

Although trends in hCG levels are clinically used to aid in the prediction of a viable IUP in women symptomatic of possible miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy, mathematical and clinical models are not completely accurate (8,9). . Our previous research (10) demonstrated that the minimal hCG rise for a viable IUP was 53% at 2 days, and that 99% of viable IUP demonstrated this rise when the hCG was <5000 mIU/mL. However, this model was developed in a relatively homogenous racial and ethnic population. Moreover, women with uncertain gestational (based on uncertain last menstrual period) were not included in the model. This factor may have limited the generalizability of the findings.

Accurate diagnosis of women presenting to the emergency room in early pregnancy with pain, with or without bleeding, is critical. If treated as a non-viable pregnancy, interruption of a potentially viable intrauterine pregnancy may result. Failure to diagnose an ectopic pregnancy increases risks of maternal morbidity and mortality if the ectopic later ruptures. Relying only on the change in hCG values can lead to misdiagnosis of women with an early symptomatic gestation (12, 13).

The current research took a diverse cohort of US women and assessed whether variation in hCG measures, used to assess early gestation viability, was associated with differences in patient risk factors and demographics. We evaluated the impact of differences in race, ethnicity, and other clinical variables such as, prior miscarriages, bleeding, or pain at presentation on the profiles of serial hCG measurements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective cohort study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Pennsylvania (Penn), the University of Southern California (USC) and the University of Miami (UM).

The cohort for this study consisted of pregnant women who presented between 2007 and 2011 to the emergency room of these 3 academic institutions with pain with or without bleeding. Patients were considered to be eligible for the study if the presenting hCG value was ≤10,000 mIU/ml, at least 2 hCG values were available separated by no more than 7 days and there was a final diagnosis of a viable IUP defined as one having fetal heart motion noted on ultrasound at 12 weeks, or later. The ultrasound scans of all patients in this cohort were reviewed and interpreted by the radiology physicians, and the ultrasound findings were communicated to the emergency department attending physician prior to the gynecology consultation. Serum hCG concentrations were quantified using chemoluminescent technique (Axysm; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) and reported in mIU/mL using the Third International Reference Preparation (average interassay coefficient of variation at the three institutions 7.8%). Information on last menstrual period, race, ethnicity (self-reported), maternal age, pain, bleeding, and obstetric history was collected at the time of initial visit. The sample size for this project represented all of the data available that meet the above criteria after four years of collection.

All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.2(SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Analyses were conducted on the natural log transformation of the hCG values to reduce the skewness of the distribution. Data presented in the tables and figures have been converted back to normal values (ie untransformed values) to aid in clarity of presentation.

The curves were modeled using two methods. As in the prior paper (10), we used a linear fixed and random effects model for natural log transformed hCG to generate the slope per respondent and the upper and lower standardized percentiles for those predicted slopes. This methodology was used to validate our previously reported findings. This method demonstrated reliability of the data from the Penn site, but this model did not validate well with the additional study sites, details below.

To accommodate data from all sites we used a curve registration approach (11). This is a nonlinear fixed and random effect model that included a random effect on the time axis. This was used to estimate a random shift in the time axis at each site and by each person relative to each other. This model shifted the curve for each respondent by an amount of days from the presentation date to generate the best fitting overall curves. By using this model, we did not need to know the date of the last menstrual period. The model computed a correction factor to adjust the starting point of the projected hCG curve on the Y axis (i.e. time), to reflect gestational age rather than stating all curves from the date each patient presented for care. The variable, called ‘tau’ or ‘normalized days since presentation’ shifted the time of the start of the curve (in days) for each respondent. The variable was composed of a specific fixed effect for their site plus a random effect due to each individual. This new day variable “lined up” the respondents based on their values and the shape of their individual curve. Because the rise of hCG is not linear, this minimized error that may be introduced if some women presenting for care earlier, or later, in gestation, where the curve shape may have a different rate of rise.

Tau’ was defined as:

Using this shift, we tested both a linear model with tau and a quadratic model:

Versions of these models were compared to determine whether the time shift could account for the effects of sites and whether a linear model would be adequate over a short range of time from presentation. In addition, covariates including race, the presence of bleeding, and other background variables were explored to determine whether different predictive models would be needed for patients with these covariates.

To determine the best method for combining the data from the three sites, we created a model with a separate parameter for each of the three sites. In a second model, we added a time shift for each site. When we added the time shift, site was no longer a significant confounder. To determine whether a linear model for these data would be adequate over a restricted range instead of a quadratic model, we compared the fit of the linear and quadratic model using likelihood ratio statistics. The quadratic model fitted the data better (see below), and was used to generate the estimates.

To create tables of predicted hCG values, we first re-ran the models taking out the fixed effects for the individual sites. The rationale for this was that when we apply this modification to the prediction of hCG values for a new site, the effect of that site would be unknown. Doing so slightly increased the variance of the prediction. We then computed the starting value of tau based on the initial hCG value. Higher hCG values shifted a person further in time from the presentation date, thus moving them into an area of the curve which had slower growth. Second, we computed the expected change in hCG values across time periods of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 7 days. Third, we estimated the percentile ranges in these values assuming a normally distributed per-person shift variable. Thus, the increase listed for the first percentile meant than only 1% of the population of patients with a viable IUP would have an increase in hCG this small or smaller.

RESULTS

We identified 1165 symptomatic women who presented with early pregnancy pain, with or without bleeding, to the emergency room at the 3 sites: Penn, USC and UM. We excluded 225 women with ectopic pregnancy, 561 with miscarriage and 94 were lost to follow-up. Two hundred-eighty-five (24.5%) women were diagnosed with a viable IUP and were included in this analysis. Of these women, 104 (36.5%) had two hCG values, 99 (34.7%) had three, 58 (20.4%) had four, and remaining 24 (8.4%) had >4 serial hCG values.

Table 1 shows patient characteristics at each of the three sites. The population of women included in this study was diverse. Overall, African American women formed 54% and White women formed 39% of the study cohort, while 8% described themselves as ‘Other’. As expected, the 3 sites differed significantly (ANOVA or chi square test) in terms of race and ethnicity. Penn and UM had higher proportions of African Americans than USC and USC and UM had significantly higher numbers of Hispanic women than Penn. The sites showed differences in initial clinical presentation: pain at presentation (more pain at USC and UM), LMP certainty (higher certainty at UM and Penn), lower gestational age noted in Penn patients than at UM and USC (9.3 and 12.9 days longer, respectively), and lower mean hCG at presentation at Penn (446 mIU/mL) followed by UM and USC (1480 and 1636 mIU/mL, respectively). The significantly lower hCG levels at Penn corresponded to the lower gestational age at presentation of these patients. Maternal age, history of prior miscarriage or ectopic, and bleeding at presentation did not vary significantly between sites.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population across the three sites

| UM (n= 81) | Penn (n= 177) | USC (n= 27) | Comparison p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year), mean (SD) | 27.2 (7.0) | 27.3 (6.8) | 27.8 (5.9) | 0.92 |

| Race | 0.001 | |||

| White | 36 (44.4) | 46 (26.0) | 26 (96.3) | |

| African-American | 45 (55.6) | 108 (61.0) | 1 (3.7) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 23 (13.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 34 (42.0) | 2 (1.1) | 26 (96.3) | <0.001 |

| History of prior Miscarriage | 24 (29.6) | 53 (29.9) | 14 (51.9) | 0.066 |

| Prior ectopic pregnancy | 6 (7.4) | 15 (8.5) | 1 (3.7) | 0.68 |

| Any bleeding at presentation | 19 (23.5) | 30 (17.0) | 6 (22.2) | 0.43 |

| Any pain at presentation | 65 (80.3) | 80 (45.2) | 19 (70.4) | 0.001 |

| Has a last menstrual period date | 81 (100) | 176 (99.4) | 27 (100) | 0.74 |

| Reports that menstrual period date is certain | 73 (90.1) | 152 (85.9) | 17 (63.0) | 0.003 |

| Reported days since last menstrual period at presentation, mean (SD) | 44.6 (20.4) | 35.3 (10.7) | 48.2 (24.3) | <0.001 |

| Initial log HCG value, mean (SD) | 7.3 (1.3) | 6.1 (1.4) | 7.4 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Initial HCG value, geometric mean | 1480 | 446 | 1636 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as N (percent) unless otherwise stated

The figure in Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx, shows the linear and quadratic models and their 95% confidence intervals. The scale of the graph was in the ‘normalized days from presentation’. The best fitting quadratic curve had an intercept of 6.24 [95% CI, 6.04, 6.45], a slope (b1) of 0.39 [95% CI, 0.38, 0.41] and a quadratic term (b2) of −0.008 [95% CI, −0.008, −0.007]. The per-person shift (the random effect) had a standard deviation of 3.45 days. The time shift for UM was 3.02 days [95% CI, 2.07, 3.97] and for USC 3.21 [95% CI, 1.74, 4.67] days. Correspondingly, the quadratic model also fitted significantly better than the linear model for data from 0 to 7 days (χ2 (1) =155.3, p >0.001), and from 0–21 days (χ2 (1) = 373.9, p <0.001). Thus, we used the quadratic model to generate the estimates.

The serial hCG curves showed significant variation (across their intercept, linear, and quadratic terms simultaneously, assessed by chi squared test) associated with race (African American vs. non-African American, p <0.001), prior miscarriage (p=0.014), presence of bleeding at presentation (p<0.001), presence of pain at presentation (p=0.002), and maternal age>34 years at presentation (p<0.001). The effects for Hispanic ethnicity, smoking and prior ectopic pregnancy were not significant (p>0.05).

Table 2 shows the overall minimum (1st percentile) increases in hCG levels over time. The overall minimum (1st percentile) rise for a viable IUP at 1-day and 2-days was faster when initial hCG was low (29% and 64% at hCG = 500 mIU/mL, respectively) and was slower when the presenting hCG was high (16% and 33% at hCG = 5000 mIU/mL, respectively). The expected minimal (1st percentile) rise in hCG for a viable IUP at 2 days was 49% (or faster) when the initial hCG was 1500 mIU/mL or less. When initial values were between 1500 and 3000 mIU/mL, the minimal rise was 40% and when the initial hCG value was > 3000 mIU/mL the minimal rise for a viable IUP was as low as 33 %.

Table 2.

Overall minimal increase in hCG concentration from initial presentation

| Initial hCG | 1 day later | 2 days later | 7 days later |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 1.37 | 1.84 | 6.43 |

| 500 | 1.29 | 1.64 | 4.28 |

| 1000 | 1.25 | 1.55 | 3.53 |

| 1500 | 1.23 | 1.49 | 3.12 |

| 2000 | 1.22 | 1.46 | 2.86 |

| 2500 | 1.20 | 1.43 | 2.66 |

| 3000 | 1.19 | 1.40 | 2.50 |

| 3500 | 1.18 | 1.38 | 2.38 |

| 4000 | 1.18 | 1.36 | 2.27 |

| 4500 | 1.17 | 1.35 | 2.17 |

| 5000 | 1.16 | 1.33 | 2.09 |

Data represent the predicted increase (multiples of initial value) at the 1st percentile for women with an ongoing intrauterine pregnancy.

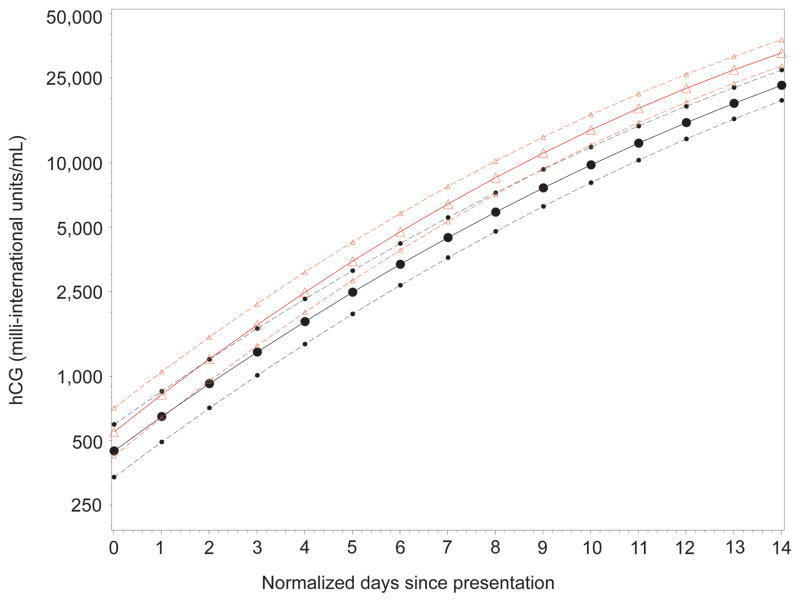

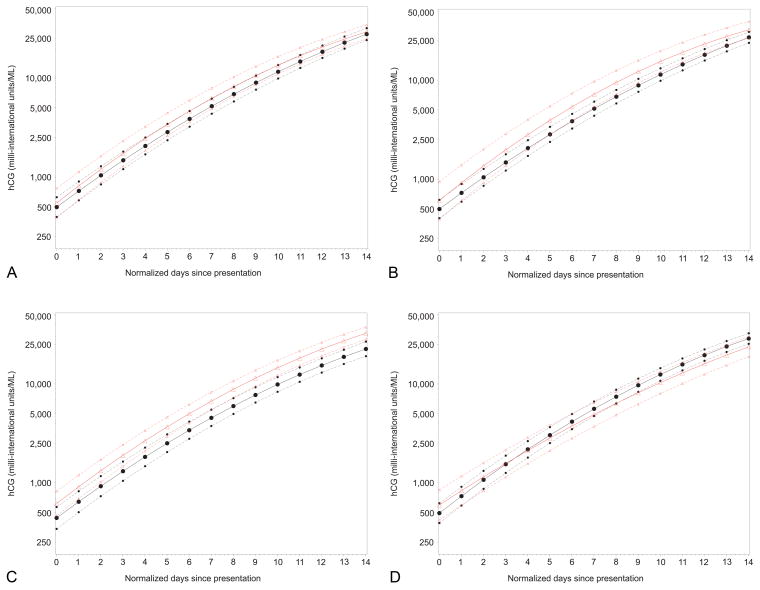

Figure 1 shows the model for AA and non-AA women. A steeper rise was observed in AA women compared to non-AA women. Figure 2 depicts the hCG curves for the other factors associated with significantly different curves. Note that prior miscarriage, presence of bleeding and presence of pain at presentation were associated with higher hCG levels over time, while maternal age>34 years was associated with a slower slope of hCG increase over time. As shown in Figure 2, some of the differences are subtle, consisting of a different initial intercept, or differences in the slope resulting in statistical significance but unlikely to reflect clinical significance.

Figure 1.

Comparison of regression curves (assuming a quadratic model), subdivided by race, for estimating hCG rise in a viable intrauterine pregnancy. Plots show untransformed hCG values with logarithmic scaling. Triangles indicate the curve for African American women and circles indicate the curve for non-African American women. Dotted lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

Comparison of regression curves (assuming a quadratic model), subdivided by significant patient factors, for estimating hCG rise in a viable intrauterine pregnancy. Plots show untransformed hCG values with logarithmic scaling. Triangles indicate the curve for (A) prior miscarriage, (B) bleeding, (C) pain, and (D) age older than 34 years. Circles indicate the absence of the relevant condition. Dotted lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3 shows the minimum (1st percentile) percentage increases in hCG levels over time for AA compared to women of other ethnicities. The difference in relative increase between AA women and non-AA women was more pronounced at low initial hCG values (500 mIU/mL) than at high initial hCG values (2500 mIU/mL). However, the 2 day minimum (1st percentile) rise in hCG for AA and non-AA at low initial hCG (500 mIU/mL) was 65% and 62%, respectively, suggesting that there was not a large clinical difference.

Table 3.

Minimal increase in hCG concentration from initial presentation for African-Americans (AA) vs. all others (Non-AA)

| Initial hCG | 1 day later | 2 days later | 4 days later | 7 days later | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | Non-AA | AA | Non-AA | AA | Non-AA | AA | Non-AA | |

| 100 | 1.38* | 1.35 | 1.86* | 1.81 | 3.24* | 3.09 | 6.56* | 6.26 |

| 500 | 1.30* | 1.28 | 1.65* | 1.62 | 2.54* | 2.49 | 4.28 | 4.29 |

| 1000 | 1.26* | 1.25 | 1.56* | 1.54 | 2.26* | 2.25 | 3.49 | 3.57 |

| 1500 | 1.24* | 1.23 | 1.50* | 1.49 | 2.10 | 2.11 | 3.07 | 3.19 |

| 2000 | 1.22* | 1.21 | 1.46 | 1.46 | 1.99 | 2.01 | 2.80 | 2.94 |

| 2500 | 1.21* | 1.20 | 1.43 | 1.43 | 1.91 | 1.93 | 2.59 | 2.75 |

| 3000 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.40 | 1.41 | 1.84 | 1.87 | 2.43 | 2.60 |

| 3500 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.38 | 1.39 | 1.78 | 1.82 | 2.30 | 2.47 |

| 4000 | 1.18 | 1.18 | 1.36 | 1.37 | 1.73 | 1.78 | 2.19 | 2.37 |

| 4500 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 1.34 | 1.35 | 1.69 | 1.74 | 2.10 | 2.28 |

| 5000 | 1.16 | 1.17 | 1.33 | 1.34 | 1.65 | 1.70 | 2.02 | 2.20 |

Data represent the predicted increase (multiples of initial value) at the 1st percentile for women with an ongoing intrauterine pregnancy.

Increase higher for AA women

We computed a linear slope for hCG rise by days from presentation separately for each site using a random intercept and slope model, as was done in our previous research (10). We used only days 0 – 10 in order to make the analysis more congruent with the analyses in the prior paper. The slope for Penn was 0.397 [95% CI, 0.381, 0.413], close to the 0.402 [0.389, 0.415]) value reported previously (10). The standard deviation of the random effect for slope was 0.074 close to the standard deviation of 0.083 found previously. However, the slopes for UM (0.282 [0.260, 0.304]) and USC (0.262 [0.223., 0.303]) were only about two-thirds of the slopes for Penn, a finding consistent with a model of decreasing slope of hCG increase as the time from LMP (gestational age and level of hCG) increases.

DISCUSSION

We have reassessed the minimal rise of hCG in a viable symptomatic IUP in a diverse group of women. a The expected minimal rise for a viable IUP was faster when the initial hCG levels were low, suggesting that one predicted slope cannot be used for all women at all times. In order to limit interruption of a potential desired IUP, a more conservative “cut off “(slower rise) is needed when hCG values are high.

A new, statistical methodology was used to address the variation in modeling hCG curves when women are unsure of their LMP (uncertain LMP occurred 10–37% across the 3 sites). This methodology innovatively shifts the hCG curve for each woman in time based on the shape of the curve and the initial hCG value. By doing so, we obtained a unique predicted hCG rise for each woman based on a curve normalized to gestational age.

This analysis addressed issues from our previous research (10) that estimation of the normal rise in hCG from initial clinical presentation may have included variation and uncertainty because the hCG curve may have a different slope at different initial values of hCG (or at different gestational ages). We have adjusted the modeled hCG curves to account for differences in hCG values by normalizing the “time of presentation” such that specific patient data contributed to the appropriate portion of the hCG curve. Women who presented early contributed to the modeling of the early portion of the curve, and women who presented late contributed to modeling of the later portion of the curve. Thus, the data presented can be applied to all women who present for care, including those unsure of their last menstrual period.

It has been previously suggested (10) that a 53% rise after 2 days will identify 99% of pregnancies that are viable, when the initial hCG <5000 mIU/mL. The current data suggest that this is likely true for women with an initial hCG value below 1500. A less stringent value however is needed for women with higher initial hCG values. The minimal rise of hCG in 2 days for women with an hCG value at 3500 was predicted to be as low as 38%, and when the value was 5000 the rise was predicted to be as low as 33%. Based on these data, it is suggested that a minimal (1st percentile) rise of 49% (or faster) is expected for initial hCG values below 1500 mIU/mL, a rise of 40% for initial hCG values 1500 – 3000 mIU/mL and a rise of 33% for initial hCG values above 3000 mIU/mL. Note, these values are rounded from the raw data to establish whole numbers that can be used as clinical rules of thumb.

While the diagnosis of the location and viability of a gestation is often made when hCG levels are high, it has been suggested (13,14) that more time should be taken to confirm viability and location before intervention to prevent the interruption of an desired viable IUP. The concept that there is a value above which a nonviable gestation (miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy) can be diagnosed if an intrauterine gestation sac is not visualized with trans-vaginal ultrasound (often called a discriminatory zone) has been challenged. If a discriminatory zone is to be used, the hCG value should be conservative (high) with suggested level of 3000 mIU/ml, or greater (14). The current data are consistent with our previous studies (that included suspected ectopic pregnancies) which identified viable IUP with curves less than 53% and as low as 35% (12, 13). Importantly, the application of this slower threshold for minimal rise may assist in preventing the inadvertent interruption of viable intrauterine pregnancies.

Repeating our analysis on a new sample of patients at our clinical site demonstrates the reliability of our previous findings, while inclusion of other sites enhanced generalizability to help us develop the minimal rise curve for viable IUP that can be applied to racially and ethnically diverse sites in the US. In doing so, we have established that hCG rise is not the same for all races in women with symptomatic early pregnancy. Overall, AA women had a faster rise in hCG compared to non-AA women. This difference was most notable at low initial hCG values. Previous studies have documented racial and ethnic differences in hCG levels during the first and second trimester (15). These differences may reflect differential trophoblast development and differentiation, and may account for known disparities in intrauterine growth and perinatal morbidity (16). This previous study showed that slower early first-trimester hCG rise was associated with infants who were of low birth weight or small for gestational age.

History of miscarriage, bleeding, pain and maternal age at presentation statistically affected the rate of hCG rise, but differences were not clinically significant. For clinical diagnosis of symptomatic early pregnancy, the hCG differences based on race, history, or symptoms are small and no change in the minimal threshold for potential viability is recommended.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health: R01HD076279 (KB, MDS), K24HD060687 (KB)

The authors thank Paul G. Whittaker, University of Pennsylvania, for providing writing and editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Shalev E, Yarom I, Bustan M, Weiner E, Ben-Shlomo I. Transvaginal sonography as the ultimate diagnostic tool for the management of ectopic pregnancy: experience with 840 cases. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:62–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)00425-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kadar N, Caldwell BV, Romero R. A method of screening for ectopic pregnancy and its indications. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58:162–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirk E, Bourne T. Predicting outcomes in pregnancies of unknown location. Womens Health. 2008;4:491–5. doi: 10.2217/17455057.4.5.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnhart KT, van Mello N, Bourne T, Kirk E, Van Calster B, Bottomley C, et al. Pregnancy of unknown location: A consensus statement of nomenclature, definitions and outcome. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:857–66. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnhart KT, Casanova B, Sammel MD, Timbers K, Chung K, Kulp JL. Prediction of location of symptomatic early gestation based solely on clinical presentation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1319–26. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818eddcf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casanova BC, Sammel MD, Chittams J, Timbers K, Kulp JL, Barnhart KT. Prediction of outcome in women with symptomatic first-trimester pregnancy: focus on intrauterine rather than ectopic gestation. Journal of Women’s Health. 2009;18:195–200. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Condous G, Claster VB, Kirk E, Haider Z, Timmerman D, Van Huffel S, et al. Clinical information does not improve the performance of mathematical models in predicting the outcome of pregnancies of unknown location. Fert Steril. 2007;88:572–580. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnhart KT. Ectopic Pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:379–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0810384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnhart KT, Katz I, Hummel A, Gracia CR. Presumed diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:505–10. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Rinaudo PF, Zhou L, Hummel A, Guo W. Symptomatic patients with an early intrauterine pregnancy: hCG curves redefined. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:50–55. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000128174.48843.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsay JO, Silverman BW. Functional Data Analysis (Springer Series in Statistics) New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seeber BE, Sammel MD, Guo W, Zhou L, Hummel A, Barnhart KT. Application of redefined human chorionic gonadotropin curves for the diagnosis of women at risk for ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:454–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morse CB, Sammel MD, Shaunik A, Allen-Taylor L, Oberfoell NL, Takacs P, et al. Performance of human chorionic gonadotropin curves in women at risk for ectopic pregnancy: exceptions to the rules. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:101–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, Blaivas M, Barnhart KT, et al. Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Multispecialty Panel on Early First Trimester Diagnosis of Miscarriage and Exclusion of a Viable Intrauterine Pregnancy. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1443–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1302417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spencer K, Ong CY, Liao AW, Nicolaides KH. The influence of ethnic origin on first trimester biochemical markers of chromosomal abnormalities. Prenat Diagn. 2000;20:491–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morse CB, Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Prochaska BA, Dokras A, Chatzicharalampous C, et al. Early rise in human chorionic gonadotropin as a marker of placentation and association with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Fertility and Sterility. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.12.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.