Abstract

To refine public health policy amidst a changing landscape of tobacco products in the United States, it is first necessary to describe fully the nature of smokers’ alternative product use. Little research addresses smokers’ snus use, and most studies are limited by small samples, cross-sectional designs, and crude outcome measurement. This study sample includes 626 adult US smokers who denied intention to quit in the next month and were randomized to receive free snus during a 6-week sampling period, after which no snus was provided. Participants were then followed for one year. Outcome data were collected via phone. Participants (mean age: 48.7 years) were predominately female, White non-Hispanic. Eighty-four percent reported trial of snus. Eleven percent reported purchase (i.e., adoption). Current use declined from 47.1% at the end of the sampling period to 6.5% at the end of follow-up. Frequency and quantity of snus use among current users was low. Among snus users, 79.3% said it functioned as an alternative to smoking and 58.4% said it provided a means of coping with smoking restrictions; options not mutually exclusive. In logistic regressions, men were more likely to report trial (odds ratio [OR]=2.33, p < .01) and adoption (OR=1.84, p < .05) than women. Baseline expectations about the nature of snus use also predicted snus outcomes (OR=1.28–1.78, p < .05). Smokers showed willingness to try snus, but product interest waned over time. Snus as currently marketed is unlikely to play a prominent role in US tobacco control efforts.

Keywords: Harm reduction, non-cigarette tobacco product, smokeless tobacco, smoking, snus, tobacco industry

1. Introduction

Conventional smokeless tobacco (chew tobacco and snuff) use has historically been low among United States (US) adults (Bhattacharyya, 2012; Fix et al., 2014; Mumford, Levy, Gitchell, & Blackman, 2006). Data from the 2000 – 2010 National Health Interview Surveys, for example, indicate only 1–2% of US adults are “regular” smokeless tobacco users (Bhattacharyya, 2012). Recently, however, the tobacco industry’s investment in smokeless tobacco increased (Federal Trade Commission, 2011; Mejia & Ling, 2010; Richardson, Ganz, Stalgaitis, Abrams, & Vallone, 2014), likely in response to an expansion of smoke-free legislation and a shift in social norms that stigmatizes smoking (Bayer & Stuber, 2006). Options for smokeless tobacco products changed with the introduction of low nitrosamine smokeless tobacco (LNST) products such as snus, an oral, spitless, pouched, and flavored tobacco. Comparative carcinogenic profiles suggest snus is less harmful than conventional tobacco products (Hatsukami, Lemmonds, Zhang, et al., 2004; Stepanov, Jensen, Hatsukami, & Hecht, 2008), including cigarettes (Lee, 2011; Levy et al., 2006; O’Connor, 2012), but it still carries health risks. The introduction of snus to the US tobacco market has not yet changed the nationwide prevalence of smokeless tobacco use (Agaku et al., 2014; Bhattacharyya, 2012; Biener et al., 2016; Boyle, Saint Claire, Kinney, D’Silva, & Carusi, 2012; Choi & Forster, 2013; Fix et al., 2014; Lee, Hebert, Nonnemaker, & Kim, 2014; Maher, Bushore, Rohde, Dent, & Peterson, 2012; Soneji, Sargent, & Tanski, 2016; Zhu et al., 2013, 2009), but there may exist subgroups of the population who are more receptive to snus than others.

Tobacco industry internal documents, marketing strategies, and advertisements all pinpoint current smokers as the intended consumer of snus (Bahreinifar, Sheon, & Ling, 2013; Mejia & Ling, 2010; Rogers, Biener, & Clark, 2010; Timberlake, Pechmann, Tran, & Au, 2011). Smokers might have interest in snus due to the: 1) perception that snus is less harmful than cigarettes (Biener & Bogen, 2009; Choi, Fabian, Mottey, Corbett, & Forster, 2012; Lund, 2012), 2) desire to circumvent smoking restrictions and temporarily mitigate nicotine withdrawal (Bahreinifar et al., 2013; Biener et al., 2016; Wray, Jupka, Berman, Zellin, & Vijayakumar, 2012), and/or 3) intention to use snus as a means of smoking reduction or cessation (Biener et al., 2016; Choi et al., 2012; Lund, 2012). Thus, snus use could function as an alternative to smoking, a complement to smoking, or both. Indeed, one of the more reliable predictors of snus (and other LNST) use is smoking status: current and former smokers are more likely to report snus use than never smokers (Biener et al., 2016; Choi & Forster, 2013; Zhu et al., 2013).

Very few population-based studies of snus use among US adult smokers exist (Biener et al., 2016; Boyle et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2014; Rath, Villanti, Abrams, & Vallone, 2012). Prior work primarily aims to determine the pervasiveness of “dual use,” and results indicate a 30-day point prevalence of snus use occurs in 3–10% of current smokers (Biener et al., 2016; Boyle et al., 2012). This literature offers insights into smokers’ willingness to try snus, but is constrained by limited outcome measurement and the fact that most studies are cross-sectional. This report aims to advance the current literature via a detailed description of snus uptake during a longitudinal study with adult US smokers who denied intention to stop smoking in the near future.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Study Overview

Adult smokers (N=1236) throughout the US who denied intention to quit in the next 30 days were recruited into a clinical trial and randomized to receive or not receive free snus during a 6-week sampling period (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01509586). After this period, participants were advised to quit all tobacco use and then followed for one year. This report focuses on the snus group (n=626). The tobacco industry did not support this study in any way. Study procedures began after approval from the Medical University of South Carolina’s institutional review board.

2.2 Eligibility Criteria

Participants met these criteria based on their self-report: 1) age ≥ 19 years; 2) English-speaking; 3) residency in the contiguous US; 4) not currently pregnant, breastfeeding, or planning to become pregnant in the near future; 5) no cardiovascular event in the past six months; 6) no smokeless tobacco use in the past six months; 7) daily smoker of ≥ 10 cigarettes per day; 8) no smoking cessation medication use in the past three months; 9) no quit attempt lasting > 1 week in the past six months; and 10) low motivation to quit smoking, operationalized as ≤ 7 on a 0 to 10 contemplation ladder (Biener & Abrams, 1991) and no stated intention to quit in the next 30 days based on stage of change assessment (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). The tobacco-specific eligibility criteria ensured recruitment of regular smokers who were “unmotivated” to quit and relatively snus-naïve.

2.3 Snus

Snus participants were offered Camel Snus (Reynolds American, Inc.), a spitless, pouched moist snuff, available in either Winterchill or Robust, both 2.5–2.8 mg nicotine per pouch (Hatsukami et al., 2015; Stepanov et al., 2012). Early testing suggested Camel Snus offers greater nicotine delivery and withdrawal/craving relief than other LNST (Hatsukami et al., 2011; Stepanov et al., 2012, 2008). Twice during the sampling period, participants were offered free samples of Camel Snus. For those who accepted this offer, up to 20 tins (300 total pouches) were mailed over four shipments.

2.4 Procedures

Knowledge Networks, which maintains national market research panels, emailed a study invitation to potential participants that contained a link to a brief study description. Interested individuals then completed an online eligibility screener. A more complete study description was provided to eligible individuals, with mention of a “new, potentially safer tobacco product” and assurances that study participation required neither use of this product nor smoking cessation. Names and contact information for eligible, interested individuals were forwarded to study staff. Enrollment in this study (November 2011–August 2013) was formalized upon attainment of written informed consent and completion of a baseline assessment via a combination of mail questionnaire and phone interview.

Participants learned their group assignment during the initial call. Snus participants received information about Camel Snus, including 1) how to use it; 2) reasons for its classification as a LNST product; and 3) cautions about product safety. Between Week 0 (post-baseline assessment) and Week 6 (after which snus was no longer offered), participants received three equally spaced calls. At each call, emphasis was placed on self-determination of snus use. After the 6-week sampling period, participants were given brief advice to quit all tobacco use and their state Quitline’s contact information; this occurred at the Week 6 call only. Six additional calls spanned the 1-year follow-up period. Of the 5,634 scheduled calls (626 * 9), 85.7% were completed. Participants were reimbursed for each complete assessment (US $130 maximum).

2.5 Measures

2.5.1 Baseline

This assessment included questions about participants’ demographic and tobacco use history, including the Heaviness of Smoking Index as a measure of nicotine dependence (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, Rickert, & Robinson, 1989). Participants also rated their concern about the personal health effects of smoking (“very or somewhat” versus “only slightly or not”), motivation to quit smoking next month (0=very definitely no to 10=very definitely yes), and confidence about quitting smoking next month (0=not at all confident to 10=extremely confident). Perceived personal harm from LNST (exclusive of electronic cigarettes) was measured on a 0=not at all harmful to 10=very much harmful scale. Finally, expectations about the likelihood of using LNST for various purposes (e.g., reduce smoking) were measured on a 0=not at all likely to 3=very likely scale.

2.5.2 Tobacco Use Outcomes

At each follow-up assessment (Week 0 to 58), participants provided information via timeline follow-back procedures. Frequency (number of days) and quantity (number of units per day) of use in the past week was measured separately for cigarettes and snus, allowing determination of current users based on 7-day point prevalence. Additionally, participants were asked about the occurrence of any snus use since the last assessment, allowing determination of continuous abstinence. Any purchase of snus since the last assessment was also ascertained. Any report of snus use triggered questions as to whether or not snus was used 1) as an alternative to smoking, i.e., a participant could smoke, but chose not to and/or 2) as a means of coping with smoking restrictions.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe participants and all study variables. No missing data were imputed to avoid assumptions regarding the occurrence of snus use. Consequently, the effective sample size varies across analyses. Binary snus outcomes include: 1) any use, 2) any frequent use (use on 6–7 days in a given week), and 3) any purchase, all based on the entire study period. Independent samples t-tests and chi-square tests were conducted to identify potential predictors of snus outcomes. All baseline variables were considered as predictors, and all predictors demonstrating a significant (p < .05) univariate relationship with a given outcome were entered simultaneously into a multivariate binomial logistic regression model for that outcome.

3. Results

3.1 Participants

Table A shows the demographic characteristics and tobacco use history of snus participants (n=626). This predominantly female, White non-Hispanic group had a mean of 48.7 years of age. Roughly half were in a relationship, received more than a high school education, and were employed. Participants had a longstanding history of daily smoking and moderate nicotine dependence. Most had a history of making a quit attempt, but few had done so in the past year. Home smoking restrictions were common. Most participants endorsed concern about the effects of smoking on their health. By design, both motivation to quit and confidence about quitting were low. Finally, participants were generally familiar with LNST, though use of these products was rare.

Table A.

Participants’ Demographic and Tobacco Use History at Baseline (n=626)

| Variable | Percent | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||

| Age, years | 48.7 (12.5) | |

| Male | 30.0 | |

| White non-Hispanic | 85.5 | |

| Married or partnered | 47.2 | |

| Post-high school education | 46.8 | |

| Employed full- or part-time | 41.8 | |

| Tobacco Use History | ||

| Nicotine dependence, Heaviness of Smoking Index | 3.5 (1.2) | |

| Age at onset of daily smoking, years | 16.9 (3.7) | |

| Cigarettes per day in a typical week | 20.1 (8.7) | |

| 24-hour smoking quit attempt, lifetime | 77.2 | |

| 24-hour smoking quit attempt, past year | 9.3 | |

| Smoking restrictions in home | 44.7 | |

| Somewhat/very concerned about personal harm from smoking | 73.7 | |

| Motivation to quit smoking a | 1.4 (2.3) | |

| Confidence about quitting smoking b | 2.6 (3.1) | |

| Heard of any LNST products | 76.0 | |

| Use of any LNST products, lifetime | 6.9 | |

| Perceived personal harm from LNST c | 5.7 (2.8) | |

| Likelihood of LNST use to reduce smoking d | 1.6 (1.1) | |

| Likelihood of LNST use to quit smoking d | 1.3 (1.1) | |

| Likelihood of LNST use to cope with smoking restrictions d | 1.6 (1.2) |

Note.

0 to 10 scale where 0=very definitely no and 10=very definitely yes;

0 to 10 scale where 0=not at all confident and 10=extremely confident;

0 to 10 scale where 0=not at all harmful and 10=very much harmful;

0 to 3 scale where 0=not at all likely and 3=very likely

3.2 Snus Use: Trial, Amount, and Adoption

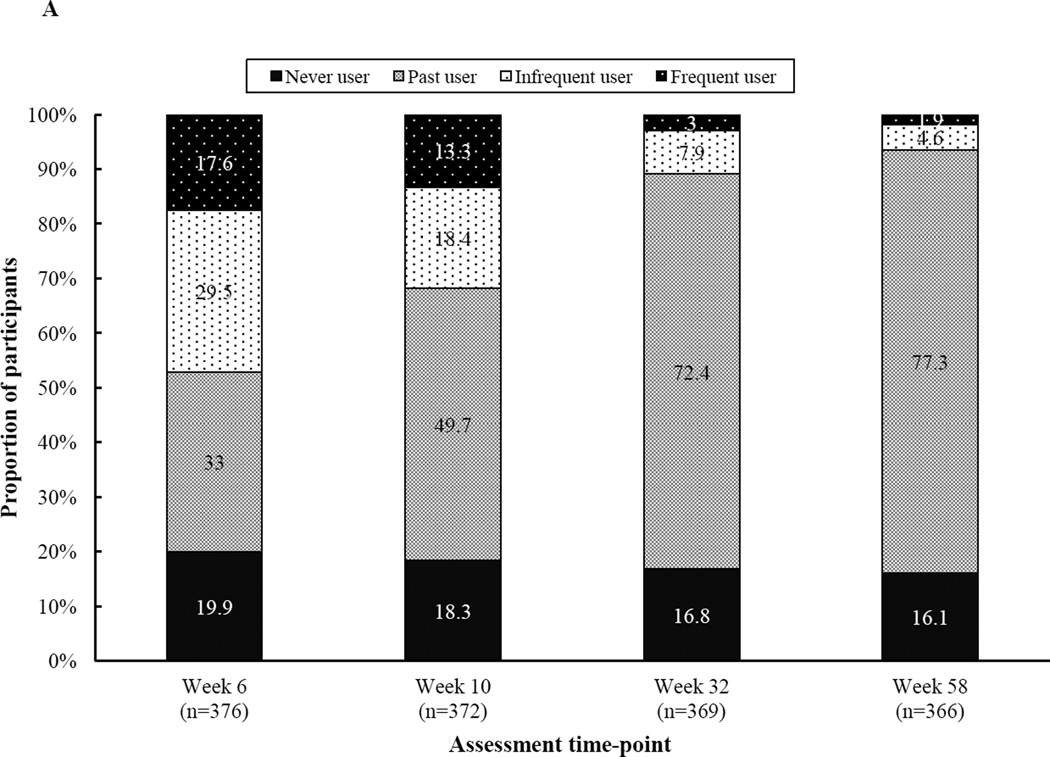

Eighty-four percent of participants reported at least one occasion of snus use (i.e., trial) on the basis of completer analyses (n=366 with complete data through Week 58). Across the entire study, 20.9% of participants reported at least one occasion of frequent snus use. Both the percentage of current users and frequent users declined between Week 6 (47.1% and 17.6%, respectively) and Week 58 (6.5% and 1.9%, respectively). The percentage of never, past, or current users at select weeks is shown in Figure A.

Figure A.

Participants’ snus use status over time (n=366–376)

Note. Snus use categories are defined as follows: 1) Never user: no snus use at any point throughout the entire study, 2) Past user: snus use on at least one occasion, but no use during the 7 days prior to the assessment, 3) Current infrequent user: snus use on 1–5 of the 7 days prior to the assessment, and 4) Current frequent user: snus use on 6–7 of the 7 days prior to the assessment. Categories are based on completer analysis, i.e., participants with no missing snus data at any time-point.

The frequency and quantity of snus use among current users appeared stable across time. Average amount of use at select time-points is based on the report of current users only: Week 6 (n=265), Week 10 (n=175), Week 32 (n=49), and Week 58 (n=22). Days of use in the past week (M ± SD) was as follows for Week 6, 10, 32, and 58: 4.0 ± 2.4, 4.3 ± 2.4, 3.8 ± 2.3, and 3.2 ± 2.2, respectively. Amount of use on using days in the past week (M ± SD) was as follows for Week 6, 10, 32, and 58: 2.9 ± 2.1, 2.8 ± 1.7, 2.5 ± 1.0, and 2.2 ± 1.2, respectively.

Adoption of snus, defined as purchase, occurred in 11.0% (n=69/626) of participants, a figure that rises to 13.1% (n=69/525) if based on those who tried snus. Repeat purchase was low: 4.5% (n=28/626) among all snus participants, 5.3% (n=28/525) among those who tried snus, and 40.6% (n=28/69) among those who made an initial purchase.

3.3 Purpose of Snus Use

Among participants who reported current snus use and answered follow-up questions about its purpose (n=469–474), 79.3% (n=372/469) said snus use functioned at least once as an alternative to smoking and 58.4% (n=277/474) said it functioned at least once as a method of coping with smoking restrictions. Roughly half of these respondents endorsed snus use for both purposes (45.2%; n=210/465) while a minority denied snus use for either purpose (7.1%, n=33/465). Among those who used snus for a singular purpose (n=222/465), it was more likely to be used as an alternative to smoking (71.6%, n=159/222) than as a means of coping with smoking restrictions (28.4%, n=63/222).

3.4 Prediction of Snus Outcomes

In univariate analyses, ten of 21 variables emerged as significant predictors of ≥ 1 snus outcomes (data not shown). Consequently, the binary logistic regression models for snus trial, frequent use, and adoption included a combination of 10 predictors (Table B). Consistent predictors across outcomes were gender and certain expectations about LNST use. First, male gender increased the odds of trial (odds ratio [OR]=2.33), frequent use (OR=2.58), and adoption (OR=1.84). Second, a higher perceived likelihood of using LNST to reduce smoking increased the odds of trial (OR=1.78) and frequent use (OR=1.45). Finally, a higher perceived likelihood of LNST use to cope with smoking restrictions increased the odds of frequent use (OR=1.28).

Table B.

Logistic Regression Models of Snus Trial and Adoption

| Snus Outcomea |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Trial (i.e., Any Use) |

Any Frequent Use (i.e., 6–7 days/week) |

Adoption (i.e., Any Purchase) |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age, years (10-year increments) | 1.28 (1.06–1.56) ** | ||

| Male (referent: female) a | 2.33 (1.27–4.29) ** | 2.58 (1.60–4.17) ** | 1.84 (1.07–3.14) * |

| 24-hour smoking quit attempt, past year (referent: no quit attempt) a | 1.51 (0.73–3.15) | ||

| Motivation to quit smoking (3-unit increments) b | 1.18 (0.88–1.60) | ||

| Heard of any LNST products (referent: no recognition) a | 2.64 (1.20–5.78) * | ||

| Use of any LNST products, lifetime (referent: never user) a | 1.77 (0.76–4.10) | ||

| Perceived personal harm from LNST (3-unit increments) c | 0.83 (0.64–1.09) | 0.89 (0.69–1.15) | |

| Likelihood of LNST use to reduce smoking (1-unit increment) d | 1.78 (1.24–2.55) ** | 1.45 (1.06–1.99) * | 1.30 (0.88–1.93) |

| Likelihood of LNST use to quit smoking (1-unit increment) d | 0.81 (0.58–1.11) | 1.02 (0.77–1.36) | 1.13 (0.81–1.57) |

| Likelihood of LNST use to cope with smoking restrictions (1-unit increment) d | 1.08 (0.84–1.39) | 1.28 (1.01–1.64) * | 1.26 (0.94–1.69) |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

0=absence of the behavior/attribute and 1=presence of the behavior/attribute;

0 to 10 scale where 0=very definitely no and 10=very definitely yes;

0 to 10 scale where 0=not at all harmful and 10=very much harmful;

0 to 3 scale where 0=not at all likely and 3=very likely;

OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval

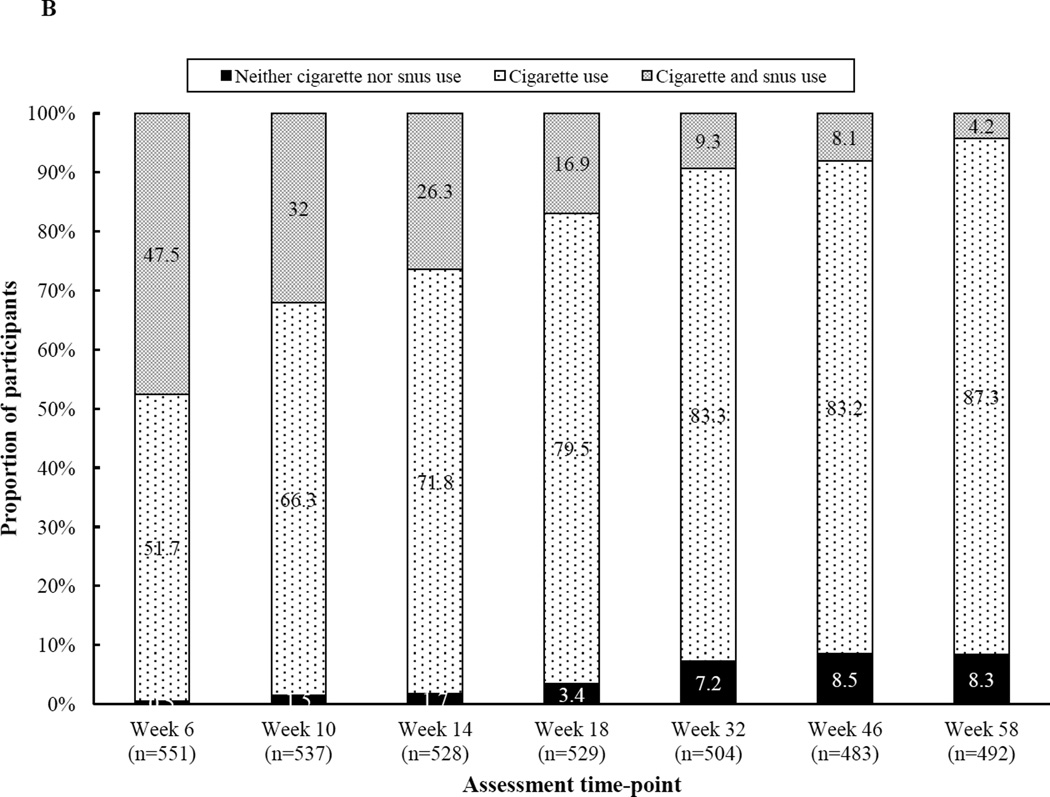

3.5 Dual Use of Snus and Cigarettes

In most cases, participants’ snus use was concurrent with continued smoking. Figure B shows the prevalence of dual use, defined as a positive 7-day point prevalence of snus and cigarette use, throughout the study. Snus use without smoking occurred in less than 1.0% (n=1) of participants. Far more common was dual use (4.2–47.5% across time) or smoking in isolation (51.7–87.3% across time), with dual use decreasing over time.

Figure B.

Participants’ 7-day point prevalence of cigarette and/or snus use by time (n=492–551)

Note. Snus use alone occurred in less than 1% of participants at each assessment, so those data are not depicted.

4. Discussion

The tobacco industry uses direct mail marketing (i.e., advertisements, coupons, promotional products, and offers for free samples) to encourage smokers’ experimentation with snus (Bahreinifar et al., 2013; Biener et al., 2016; Brock, Schillo, & Moilanen, 2015). To create a naturalistic setting in which to observe snus trial and adoption among a nationwide sample of “unmotivated” adult smokers in the US, this study mimicked the tobacco industry’s direct-to-consumer approach by delivering snus samples via mail. Snus was provided free of charge for ad libitum use, and there was minimal tobacco cessation treatment delivery. This novel methodological approach to the study of alternative tobacco products optimizes the ecological validity of study findings, as it created a situation in which snus use was neither contrived nor mandated as part of study participation. This longitudinal study describes in detail the nature of snus uptake among a large group of US smokers, and it represents a necessary first step toward refinement of tobacco control policy amidst a changing landscape of tobacco products.

Participants showed willingness to try snus, but their interest in this product waned significantly over time. The prevalence of current users changed from 47.1% at the end of the 6-week sampling period to 6.5% a year later, an 86.2% reduction. Frequent use, which was prevalent in 20.9% of participants, mainly occurred in the early months of the study. Furthermore, amount of snus use was low throughout the study. Interpretation of these data, though, must account for the fact that dual use of cigarettes and snus was the norm. Most US population-based reports of snus use describe cross-sectional studies and categorize participants as “never,” “former,” or “current” users and/or categorize frequency of use as “every day,” “some days,” “rarely,” or “not at all” (Agaku et al., 2014; Biener et al., 2016; Boyle et al., 2012; Choi & Forster, 2013; Lee et al., 2014; Rath et al., 2012; Soneji et al., 2016), making it difficult to compare our findings with prior studies. Two other US sampling studies (n’s < 200) provide some help in this regard, as both found an average snus use of approximately 3 pouches/day during a 5–7 day period of concomitant smoking (Krautter, Chen, & Borgerding, 2015; O’Connor et al., 2011). The quantity of snus use reported here is consistent with these studies. Nonetheless, future studies need to replicate these findings, and would be strengthened by technological approaches that allow fine-grained, real-time tobacco use assessment. (Dallery, Kurti, & Martner, 2015).

This study adds to the LNST literature by exploring adoption of snus use as a new, potentially long-term tobacco use behavior. Many health behavior change models and applications consider adoption of a new behavior as a function of time (e.g., maintenance of X behavior six months post-intervention) (Hughes, Keely, & Naud, 2004; Prochaska & Velicer, 1997; Williams, Niemiec, Patrick, Ryan, & Deci, 2009; Ziegelmann, Lippke, & Schwarzer, 2006), but it was operationalized here in strictly behavioral terms. Due to the nature of the eligibility criteria and no knowledge of a pouch to cigarette conversion rate, full/partial substitution was ruled out as the criterion for adoption. This led us to define adoption as purchase, consistent with marketing and business models (Gourville, 2003). With 11.0% of participants reporting purchase, we report a low rate of adoption, with one caveat: snus was possibly over-supplied. For current users at any given time, frequency of use was basically every-other-day and amount of use was 2–3 pouches per using day. These data, in combination with a reduction in the prevalence of current users over time, suggest the amount of snus we made available probably exceeded participants’ needs (see (O’Connor et al., 2011) for a similar result). Consequently, our criterion for adoption has its shortcomings.

Most advertisements highlight snus’ utility in situations where smoking is prohibited (indirectly marketing dual use of cigarettes and snus) (Timberlake et al., 2011), but some promote switching from cigarettes to snus (indirectly marketing snus as a means of smoking cessation) (“Camel Snus [advertisement],” 2011). As advertised, many participants said snus served multiple purposes, including as a means of coping with smoking restrictions and an alternative to smoking. The latter purpose does not necessarily reflect intent to switch products, but it does support smokers’ willingness to try snus as a temporary replacement for the far more established behavior of smoking (O’Connor et al., 2011). Baseline expectations about snus use for a specific purpose predicted trial and frequent use in this study, supporting the theoretical link between intention and behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Rogers, 1983; Triandis, 1977). The intention behind snus use is important, especially since another randomized clinical trial with “unmotivated” smokers found change in smoking dependent upon the prescribed nature of snus use during a 2-week sampling period (Burris, Carpenter, Wahlquist, Cummings, & Gray, 2014). Specifically, individuals instructed to use snus as a means of coping with smoking restrictions reported a reduction in cigarettes per day that was far lower than that reported by those instructed to use snus as a means of smoking reduction (Burris et al., 2014). Furthermore, among smokers who report readiness to quit, snus use shows some efficacy for smoking cessation in randomized clinical trials (Fagerstrom, Rutqvist, & Hughes, 2012; Hatsukami et al., 2015; Joksić, Spasojević-Tišma, Antić, Nilsson, & Rutqvist, 2011; Tønnesen, Mikkelsen, & Bremann, 2008). Consequently, if the tobacco control community chooses to advocate for snus as a means of harm reduction–a topic which is still up for debate (Hatsukami, Ebbert, Feuer, Stepanov, & Hecht, 2007; Hatsukami, Lemmonds, & Tomar, 2004; Levy et al., 2006; O’Connor, 2012; Tomar, 2007)–then messaging around the purpose of snus use must be clear.

The aforementioned study findings must be considered in light of study limitations. First, a single snus product was offered. At the outset of this study, Camel Snus was one of the most aggressively marketed and widely available LNST products in the US (Bahreinifar et al., 2013; Delnevo et al., 2014; Rogers et al., 2010), and laboratory studies suggested consumers preferred it over other LNST products (Hatsukami et al., 2011; Stepanov et al., 2012, 2008). While Camel Snus was selected for this study because it appeared to be the most appealing LNST product to smokers, it is possible features of this product influenced study outcomes. Second, the study population consisted of smokers who reported little to no interest in smoking cessation. This was due to concern about the ethical implications of providing tobacco to treatment-seeking smokers along with the desire to capture snus use among the group of smokers who are most widely represented in the US/Canadian population (i.e., smokers without intention to quit in the near future) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; Cunningham, Kushnir, & McCambridge, 2016; Wewers, Stillman, Hartman, & Shopland, 2003). Nonetheless, some research shows snus use is positively associated with indicators of motivation to quit smoking, including a recent quit attempt (Kalkhoran, Grana, Neilands, & Ling, 2015; Schauer, Pederson, & Malarcher, 2016; Zhu et al., 2013). Given this, the generalizability of this study is limited to “unmotivated” smokers, a group one might expect to have a lower likelihood of snus use than smokers who are ready to quit smoking and view snus as a quit aid. Finally, White, non-Hispanics and females are both over-represented in this US sample (United States Census Bureau, 2015).

4.1 Conclusions

This study found that when “unmotivated” smokers are offered free snus for a finite period of time, most will try it, but only a fraction will become regular snus users, and most of these individuals will stop snus use altogether after a few months. The removal of any start-up costs for snus use, including cost for the product itself and cost related to travel to obtain said product, helped ensure study outcomes were not a function of access. Consequently, there likely exist aspects of the product, the consumer, and/or the environment that limit snus uptake in this population. The results of surveys, focus groups, and lab studies point toward dislike of the taste, oral sensation, and packaging of snus (Bahreinifar et al., 2013; Biener et al., 2016), in addition to dissatisfaction with nicotine delivery and suppression of withdrawal/craving (Blank & Eissenberg, 2010; Hatsukami et al., 2015), as reasons for smokers’ discontinuation of snus use. Additionally, some smokers’ perception of themselves as a “smoker” and not a “snuser” or “dual user” may reduce the likelihood of regular snus use (Bahreinifar et al., 2013). Finally, the initial appeal of snus (and its inherent smokeless quality) may subside as tobacco control shifts from smoke-free legislation to tobacco-free legislation. Taken together, the current evidence indicates that snus as currently marketed is unlikely to play a prominent role–either positive or negative–in tobacco control efforts in the US.

Highlights.

Most US smokers with low quit intention tried snus when offered it for free

After 3–4 months, most of these smokers stopped regular snus use

Frequency and quantity of snus use among current users were consistently low

Male gender and initial expectations about snus use predicted snus use outcomes

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledgement the work of all research assistants who contributed to the conduct of this study, including but not limited to Amy Boatright, Nichols Mabry, Easha Tiwari, and Caitlyn Hood.

Author Disclosure Role of Funding Sources

This work was supported the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01 CA154992 to M.J.C., K07 CA181351 to J.L.B, and P30 CA138313 to A.J.A.); and the National Center for Advancing Translational Science at the National Institutes of Health (grant number UL1 TR000062). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. The funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Cummings has received grant funding from Pfizer, Inc. to study the impact of hospital-based tobacco cessation treatment. Cummings also receives funding as an expert witness in litigation filed against the tobacco industry.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Carpenter was the principal investigator and took the lead in study design. Burris led data analysis and interpretation for this study in addition to being principally responsible for writing this manuscript. All authors contributed to the preparation of this manuscript, including editing, and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Alberg, Burris, Carpenter, Garrett-Mayer, Gray, and Wahlquist have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Agaku IT, King BA, Husten CG, Bunnell R, Ambrose BK, Hu SS, et al. Tobacco product use among adults — United States, 2012–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63:542–547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. http://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [Google Scholar]

- Bahreinifar S, Sheon NM, Ling PM. Is snus the same as dip? Smokers’ perceptions of new smokeless tobacco advertising. Tobacco Control. 2013;22:84–90. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050022. http://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer R, Stuber J. Tobacco control, stigma, and public health: Rethinking the relations. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:47–50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071886. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.071886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya N. Trends in the use of smokeless tobacco in United States, 2000–2010. The Laryngoscope. 2012;122:2175–2178. doi: 10.1002/lary.23448. http://doi.org/10.1002/lary.23448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, Abrams DB. The contemplation ladder: Validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 1991;10:360–365. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.360. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.70.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, Bogen K. Receptivity to Taboka and Camel Snus in a U.S. test market. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2009;11:1154–1159. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp113. http://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, Roman AM, McInerney SA, Bolcic-Jankovic D, Hatsukami DK, Loukas A, et al. Snus use and rejection in the USA. Tobacco Control. 2016;25:386–392. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051342. http://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank MD, Eissenberg T. Evaluating oral noncombustible potential-reduced exposure products for smokers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2010;12:336–343. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq003. http://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntq003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle RG, Saint Claire AW, Kinney AM, D’Silva J, Carusi C. Concurrent use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco in Minnesota. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/493109. no pagination. http://doi.org/10.1155/2012/493109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock B, Schillo BA, Moilanen M. Tobacco industry marketing: an analysis of direct mail coupons and giveaways. Tobacco Control. 2015;24:505–508. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051602. http://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris JL, Carpenter MJ, Wahlquist AE, Cummings KM, Gray KM. Brief, instructional smokeless tobacco use among cigarette smokers who don’t intend to quit: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2014;16:397–405. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [Retrieved January 5, 2012];Camel Snus [advertisement] 2011 from http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/ad_gallery/ad/great_time_to_quit.

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Quitting smoking among adults — United States, 2001–2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;60:1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Fabian L, Mottey N, Corbett A, Forster J. Young adults’ favorable perceptions of snus, dissolvable tobacco products, and electronic cigarettes: Findings from a focus group study. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:2088–2093. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300525. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Forster J. Awareness, perceptions and use of snus among young adults from the upper Midwest region of the USA. Tobacco Control. 2013;22:412–417. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050383. http://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Kushnir V, McCambridge J. The impact of asking about interest in free nicotine patches on smokers’ stated intention to change: Real effect or artefact of question ordering? Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2016;18:1215–1217. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv173. http://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Kurti A, Martner S. Technological approaches to assess and treat cigarette smoking. In: Marsch LA, Lord SE, Dallery J, editors. Behavioral healthcare and technology: Using science-based innovations to transform practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015. pp. 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Delnevo CD, Wackowski OA, Giovenco DP, Bover Manderski MT, Hrywna M, Ling PM. Examining market trends in the United States smokeless tobacco use: 2005–2011. Tobacco Control. 2014;23:107–112. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050739. http://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom K, Rutqvist LE, Hughes JR. Snus as a smoking cessation aid: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2012;14:306–312. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr214. http://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Trade Commission. Smokeless tobacco report for the year 2007 and 2008. Washington, DC: 2011. Retrieved from http://www.ftc.gov/os/2011/07/110729smokelesstobaccoreport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Fix BV, O’Connor RJ, Vogl L, Smith D, Bansal-Travers M, Conway KP, et al. Patterns and correlates of polytobacco use in the United States over a decade: NSDUH 2002–2011. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:768–781. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.12.015. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourville JT. Harvard Business Review. Boston: Harvard Business Publishing; 2003. Why consumers don’t buy: The psychology of new product adoption (case study) [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami DK, Ebbert JO, Feuer RM, Stepanov I, Hecht SS. Changing smokeless tobacco products: New tobacco-delivery systems. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33:368–378. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.005. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami DK, Jensen J, Anderson A, Broadbent B, Allen S, Zhang Y, Severson H. Oral tobacco products: Preference and effects among smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.026. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami DK, Lemmonds C, Tomar SL. Smokeless tobacco use: Harm reduction or induction approach? Preventive Medicine. 2004;38:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.10.006. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami DK, Lemmonds C, Zhang Y, Murphy SE, Le C, Carmella SG, Hecht SS. Evaluation of carcinogen exposure in people who used “reduced exposure” tobacco products. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004;96:844–852. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh163. http://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djh163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami DK, Severson H, Anderson A, Vogel RI, Jensen J, Broadbent B, et al. Randomised clinical trial of snus versus medicinal nicotine among smokers interested in product switching. Tobacco Control. 2015:1–8. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052080. http://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: Using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Addiction. 1989;84:791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joksić G, Spasojević-Tišma V, Antić R, Nilsson R, Rutqvist LE. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of Swedish snus for smoking reduction and cessation. Harm Reduction Journal. 2011;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-8-25. http://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkhoran S, Grana RA, Neilands TB, Ling PM. Dual use of smokeless tobacco or e-cigarettes with cigarettes and cessation. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2015;39:276–284. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.39.2.14. http://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.39.2.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautter GR, Chen PX, Borgerding MF. Consumption patterns and biomarkers of exposure in cigarette smokers switched to snus, various dissolvable tobacco products, dual use, or tobacco abstinence. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2015;71:186–197. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.12.016. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PN. Summary of the epidemiological evidence relating snus to health. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2011;59:197–214. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2010.12.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, Kim AE. Multiple tobacco product use among adults in the United States: Cigarettes, cigars, electronic cigarettes, hookah, smokeless tobacco, and snus. Preventive Medicine. 2014;62:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.01.014. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DT, Mumford EA, Cummings KM, Gilpin EA, Giovino GA, Hyland A, et al. The potential impact of a low-nitrosamine smokeless tobacco product on cigarette smoking in the United States: Estimates of a panel of experts. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1190–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.010. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund KE. Association between willingness to use snus to quit smoking and perception of relative risk between snus and cigarettes. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2012;14:1221–1228. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts077. http://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nts077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher JE, Bushore CJ, Rohde K, Dent CW, Peterson E. Is smokeless tobacco use becoming more common among U.S. male smokers? Trends in Alaska. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:862–865. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.015. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia AB, Ling PM. Tobacco industry consumer research on smokeless tobacco users and product development. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:78–87. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152603. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.152603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumford EA, Levy DT, Gitchell JG, Blackman KO. Smokeless tobacco use 1992-2002: Trends and measurement in the Current Population Survey-Tobacco Use Supplements. Tobacco Control. 2006;15:166–171. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012807. http://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2005.012807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RJ. Non-cigarette tobacco products: What have we learnt and where are we headed? Tobacco Control. 2012;21:181–190. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050281. http://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RJ, Norton KJ, Bansal-Travers M, Mahoney MC, Cummings KM, Borland R. US smokers’ reactions to a brief trial of oral nicotine products. Harm Reduction Journal. 2011;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-8-1. http://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1997;12:38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath JM, Villanti AC, Abrams DB, Vallone DM. Patterns of tobacco use and dual use in US young adults: The missing link between youth prevention and adult cessation. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/679134. http://doi.org/10.1155/2012/679134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A, Ganz O, Stalgaitis C, Abrams D, Vallone D. Noncombustible tobacco product advertising: How companies are selling the new face of tobacco. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2014;16:606–614. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt200. http://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntt200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JD, Biener L, Clark PI. Test marketing of new smokeless tobacco products in four U.S. cities. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2010;12:69–72. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp166. http://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RW. Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. In: Cacioppo BL, Petty LL, editors. Social psychophysiology: A source book. London: Guilford; 1983. pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Schauer GL, Pederson LL, Malarcher AM. Past year quit attempts and use of cessation resources among cigarette-only smokers and cigarette smokers who use other tobacco products. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2016;18:41–47. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv038. http://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soneji S, Sargent J, Tanski S. Multiple tobacco product use among US adolescents and young adults. Tobacco Control. 2016;25:174–180. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051638. http://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanov I, Biener L, Knezevich A, Nyman AL, Bliss R, Jensen J, et al. Monitoring tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines and nicotine in novel Marlboro and Camel smokeless tobacco products: Findings from Round 1 of the New Product Watch. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2012;14:274–281. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr209. http://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanov I, Jensen J, Hatsukami D, Hecht SS. New and traditional smokeless tobacco: Comparison of toxicant and carcinogen levels. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2008;10:1773–1782. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443544. http://doi.org/10.1080/14622200802443544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake DS, Pechmann C, Tran SY, Au V. A content analysis of Camel Snus advertisements in print media. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2011;13:431–439. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr020. http://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomar SL. Epidemiologic perspectives on smokeless tobacco marketing and population harm. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33:S387–S397. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tønnesen P, Mikkelsen K, Bremann L. Smoking cessation with smokeless tobacco and group therapy: An open, randomized, controlled trial. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2008;10:1365–1372. doi: 10.1080/14622200802238969. http://doi.org/10.1080/14622200802238969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC. Interpersonal behaviour. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. [Retrieved July 8, 2015];State and county QuickFacts. 2015 from quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html.

- Wewers ME, Stillman F, Hartman AM, Shopland DR. Distribution of daily smokers by stage of change: Current population survey results. Preventive Medicine. 2003;36(6):710–720. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00044-6. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC, Niemiec CP, Patrick H, Ryan RM, Deci EL. The importance of supporting autonomy and perceived competence in facilitating long-term tobacco abstinence. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;37:315–324. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9090-y. http://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9090-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray RJ, Jupka K, Berman S, Zellin S, Vijayakumar S. Young adults’ perceptions about established and emerging tobacco products: results from eight focus groups. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2012;14:184–190. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr168. http://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S-H, Gamst A, Lee M, Cummins S, Yin L, Zoref L. The use and perception of electronic cigarettes and snus among the U.S. population. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079332. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S-H, Wang JB, Hartman A, Zhuang Y, Gamst A, Gibson JT, et al. Quitting cigarettes completely or switching to smokeless tobacco: Do US data replicate the Swedish results? Tobacco Control. 2009;18:82–87. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.028209. http://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2008.028209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegelmann JP, Lippke S, Schwarzer R. Adoption and maintenance of physical activity: Planning interventions in young, middle-aged, and older adults. Psychology and Health. 2006;21:145–163. doi: 10.1080/1476832050018891. http://doi.org/10.1080/1476832050018891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]