Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of second uterine curettage in lieu of chemotherapy for patients with low-risk, nonmetastatic gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN), and to evaluate if response to second curettage is independent of patient age, World Health Organization (WHO) risk score, registration human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level, lesion size and depth of myometrial invasion measured on ultrasound examination.

Methods

This was a cooperative group multi-center prospective phase II study. Prestudy testing included quantitative hCG, pelvic ultrasound, and chest X-ray. Patients were categorized according to the WHO risk scoring criteria (low risk with a score of 0 – 6).

Results

Sixty-four women with newly diagnosed low-risk, non-metastatic GTN were enrolled. Four patients were excluded. Twenty-four patients (40%) (lower 95% confidence limit: 27.6%) were cured after second curettage. An additional two patients (3%) achieved a complete response but did not complete follow-up. Overall, 26 of 60 patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. Surgical failure was observed in 34 women (59%) and was more common in women <=19 or >=40 years old. One case of grade 1 uterine perforation was successfully managed by observation. Four grade 1 and one grade 3 uterine hemorrhages were reported. New metastatic disease (lung) was identified in one of these women after second curettage. In 3 patients (surgical failures), the second curettage pathology was placental site trophoblastic tumor, and it was placental nodule in 1 additional patient.

Conclusion

Second uterine curettage as initial treatment for low-risk, non-metastatic GTN cures 40% of patients without significant morbidity.

Précis

Second uterine curettage as initial treatment for low-risk, nonmetastatic gestational trophoblastic neoplasia cures 40% of patients without significant morbidity.

Introduction

Low risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) is a highly curable disease that typically requires 5 – 7 cycles of single-agent chemotherapy with either methotrexate or actinomycin-D to achieve a cure. If second curettage can safely cure GTN and avoid chemotherapy for a significant number of women, it is an important advance in the care of these patients. Historically, gynecologists in a few trophoblastic treatment centers have routinely performed a second uterine curettage for patients with persistent GTN. Other expert centers have maintained that the risk of second curettage exceeds the benefit and thus limited this procedure to patients with heavy bleeding. Regardless of the indication, single institution retrospective reports show inconsistent outcomes with success ranging from 9 to 60%, and uterine perforation occurring as often as 8% of these procedures.1–11

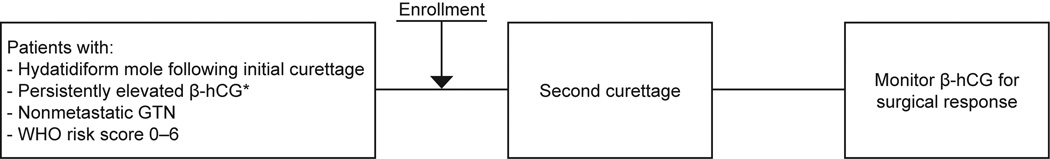

Given these widely disparate outcomes ranging from not effective to highly effective a multi-center cooperative group trial was indicated. To address this important question the Gynecologic Oncology Group initiated this prospective two-stage single arm phase II study of second curettage, in October 2007, as first-line treatment for non-metastatic, low-risk persistent trophoblastic disease (GTN).12 (Figure 1) The intent of this study was to better define the efficacy and safety of second curettage in patients with persistent, non-metastatic low risk GTN.

Figure 1.

The study schema (Gynecologic Oncology Group study no. 242).

Materials and Methods

Study eligibility required potential participants to have either a complete or partial mole at their first curettage, clinical staging (pelvic ultrasound, chest X-ray and quantitative hCG assay) and a WHO risk score of 0 – 6 to enroll in the study (Table 1). Note that since GTN patients are rescored at each recurrence, a patient failing first line therapy could remain low-risk (WHO score 0 – 6) but these patients were not eligible for this study. Patients with a positive or a suspicious chest X-ray were not eligible. Diagnostic slides and pathology reports from the first curettage were reviewed centrally after enrollment. Patients with a first curettage diagnosis of choriocarcinoma, placental-site trophoblastic tumor or epithelioid trophoblastic tumor were not eligible. Patients with an initial registration hCG level < 20 mIU/mL were also not eligible in order to minimize inclusion of patients with false positive hCG tests from circulating heterophilic antibody.13 Prior chemotherapy was an exclusion criterion.

Table 1.

Patient and Disease Characteristics

| Characteristic | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | 10–19 | 4 | 6.7 |

| 20–29 | 21 | 35.0 | |

| 30–39 | 29 | 48.3 | |

| 40–49 | 4 | 6.7 | |

| 50–59 | 2 | 3.3 | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino | 17 | 28.3 |

| Non-Hispanic | 37 | 61.7 | |

| Not reported | 6 | 10.0 | |

| Race | Not reported | 6 | 10.0 |

| Asian | 7 | 11.7 | |

| Black/African American | 8 | 13.3 | |

| Am Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 | 1.7 | |

| Native Hawaiian/PI | 1 | 1.7 | |

| White | 37 | 61.7 | |

| Molar Class | Complete mole | 54 | 90.0 |

| Partial Mole | 6 | 10.0 | |

| WHO Score | 0 | 12 | 20.0 |

| 1 | 12 | 20.0 | |

| 2 | 16 | 26.7 | |

| 3 | 9 | 15.0 | |

| 4 | 6 | 10.0 | |

| 5 | 2 | 3.3 | |

| 6 | 3 | 5.0 | |

| Registration hCG (mIU/mL) | 20.1–100.0 | 1 | 1.7 |

| 100.1–1500.0 | 19 | 31.7 | |

| 1500.1–5000.0 | 10 | 16.7 | |

| 5000.1–10000.0 | 7 | 11.7 | |

| 10000.1–100000.0 | 20 | 33.3 | |

| 100000.1–1000000.0 | 3 | 5.0 |

Prior to registration, all patients underwent a pelvic ultrasound examination measuring the volume of intra-uterine disease in three dimensions. Lesion size was determined to be the largest of these dimensions. The maximal depth of myometrial invasion was measured in one dimension. All patients also underwent either a staging chest X-ray or, less frequently, a computed tomography scan of the chest. If the computed tomography scan of the chest was negative, it was inferred that a chest x-ray, the test of choice, would also have been negative. A quantitative hCG assay was obtained on all patients prior to registration. The particular assay used was not specified in the study protocol.13,14 Patient demographics were obtained at registration and included patient age, race and ethnicity and type of molar pregnancy. Informed consent was obtained from interested, study-eligible patients who then underwent a second uterine curettage at a Gynecologic Oncology Group member institution within 14 days of registration. Local Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval of the study was obtained for all participating sites. Surgical cure was defined as achievement of a normal hCG level followed by a minimum of 6 months of continued normal hCG testing.14 Surgical response was defined as achievement of a normal hCG level but less than 6 months of completed normal testing. Surgical failure was deemed to be a rise or plateau in the hCG level as defined by the F.I.G.O. (2000) definition of persistent gestational trophoblastic neoplasia or the presence of malignant trophoblast such as placental site trophoblastic tumor in the second curettings.15 Adverse events were defined and graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v3.0. The pathology from both the initial and second curettages was centrally reviewed post hoc by two pathologists.

The method of evacuation was not specified but could include intra-operative ultrasound localization of residual trophoblast or directed hysteroscopic resection, patients could have had either or both procedures as well as no imaging..5,14 Patients were then followed post-operatively with weekly quantitative hCG levels beginning 14 days after the procedure. If the hCG reached the institutional normal, the hCG level was to be obtained monthly for 6 additional months. In patients whose hCG level rose or plateaued based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (F.I.G.O.) 2000 criteria, second curettage was deemed to have failed (surgical failure) and disease was to be re-staged and a new risk score determined.15,16 Patients were to be followed for a minimum of 24 months or until cure with chemotherapy if surgical management failed.17–19

In the study design, a rate of surgical cure of 25% or higher was considered clinically significant and a rate of 10% or less was evidence of insufficient activity.

An optimal but flexible two-stage design with early stopping guidelines intended to limit accrual of patients to an inactive treatment was used.20 Surgical cure reported in > 9 out of 60 eligible patients would be interpreted as a positive study. The intention of the design was to limit type II error to 10% and type I error to 0.05. Exact confidence intervals for proportion cured accounting for interim analyses were constructed.21,22

The primary objective was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of second curettage in this patient population. Secondary objectives included the frequency and severity of adverse events and exploratory assessment of prognostic factors. The maximum grade of acute adverse events within a category, regardless of attribution, was tabulated for eligible patients who underwent a second curettage. The quantitative hCG level measured at registration and just prior to second evacuation (both as continuous variables and as discrete variables using cutoffs of 1,500 or 5,000 mIU/mL), the presence or absence of myometrial invasion, WHO risk score, age and race were assessed for their relationship with response to second evacuation using standard tests for categorical variables or logistic regression and estimation of the concordance proportion.23

Results

From October 2007 to February 2013, 64 women were registered in the study and underwent second curettage, four were subsequently deemed ineligible after central review. Three women were excluded for an initial WHO risk score of 7 (high-risk) and one with an uncertain histologic diagnosis. Therefore, data from 60 women were included in this analysis.

Demographic information was collected on all patients with a representative sampling of ethnic groups and reproductive ages (Table 1). Fifty-four patients (90%) had a pretreatment diagnosis of complete mole and six (10%) with a partial mole based on central pathology review. There was one patient (2%) registered with an hCG level <100 mIU/mL and three women (5%) with an hCG level at registration >100,000 mIU/mL. Twelve patients (20%) had a WHO risk score of zero but two had a score of 5 (3%) and three (5%) had a score of 6. The median follow-up duration was 24 months.

Twenty-four (24/60) women were successfully treated with second curettage and did not require chemotherapy, for a surgical cure rate of 40%. Two patients (3%) did not complete follow-up (considered a surgical response) but both had achieved a normal hCG level before being lost-to-follow up, overall 28 of 60 patients were able to avoid chemotherapy. The 95% lower confidence limit for the surgical cure was 27.6%. This value is above 10% and excludes 25%, the minimal clinical effect defined in the study. Twenty-nine women (48%) developed persistent GTN as demonstrated by a rise or plateau in the hCG level, or new metastatic disease (1 developed pulmonary disease and endometrial stromal sarcoma). (Table 2)

Table 2.

Disease and treatment outcomes

| Endpoint | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reason off therapy | Completed regimen | 24 | 40.0 |

| Disease Progression | 29 | 48.3 | |

| Patient Refused/Other | 7 | 11.7 | |

| Surgical Response | Surgical Cure | 24 | 40.0 |

| Surgical Response | 2 | 3.3 | |

| Surgical Failure | 29 | 48.3 | |

| Indeterminate | 5 | 8.3 | |

| Disease status | No new disease | 59 | 98.3 |

| New metastatic disease | 1 | 1.7 | |

| Survival status | Alive | 60 | 100.0 |

Surgical cure was defined as achievement of a normal hCG level followed by a minimum of 6 months of continued normal hCG testing.14 Surgical response was defined as achievement of a normal hCG level but less than 6 months of completed normal testing. Surgical failure was deemed to be a rise or plateau in the hCG level as defined by the F.I.G.O. (2000) definition of persistent gestational trophoblastic neoplasia or the presence of malignant trophoblast such as placental site trophoblastic tumor in the second curettings.15

When patient age at study entry was considered with respect to the extremes of reproductive age, a known risk factor for GTN, disease was cured in only 1 of 4 women less than 19 years of age and 1 of 6 women aged 40 or older. In contrast, 22 of 50 (44%) women between 20 and 39 years of age were cured by second curettage alone with 49% (24/50) treatment success when surgical responses and cures were combined. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Prognostic features and response category

| Characteristic | Surgical Cure | All Patients | Chi-Square Test* p-value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical Cure |

No Surgical Cure |

||||||

| All Patients | 24 | 40.0 | 36 | 60.0 | 60 | NA | |

| Patient Group | 0.98 | ||||||

| Mass noted, no myometrial invasion noted | 9 | 40.9 | 13 | 59.1 | 22 | 36.7 | |

| Mass with myometrial invasion | 8 | 38.1 | 13 | 61.9 | 21 | 35.0 | |

| No mass noted | 7 | 41.2 | 10 | 58.8 | 17 | 28.3 | |

| WHO Score Category | 0.06 | ||||||

| WHO score ≤ 4 | 24 | 43.6 | 31 | 56.4 | 55 | 91.7 | |

| WHO score > 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 100 | 5 | 8.3 | |

| Registration beta hCG (mIU/mL) | 0.51 | ||||||

| 20.1–100.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 1.7 | |

| 100.1–1500.0 | 10 | 52.6 | 9 | 47.4 | 19 | 31.7 | |

| 1500.1–5000.0 | 4 | 40.0 | 6 | 60.0 | 10 | 16.7 | |

| 5000.1–10000.0 | 2 | 28.6 | 5 | 71.4 | 7 | 11.7 | |

| 10000.1–100000.0 | 8 | 40.0 | 12 | 60.0 | 20 | 33.3 | |

| 100000.1–1000000.0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 3 | 5.0 | |

| Registration hCG (mIU/mL) at least 700 | 0.80 | ||||||

| hCG < 700 | 6 | 42.9 | 8 | 57.1 | 14 | 23.3 | |

| hCG ≥ 700 | 18 | 39.1 | 28 | 60.9 | 46 | 76.7 | |

| Registration hCG (mIU/mL) at least 1500 | 0.20 | ||||||

| hCG < 1500 | 10 | 50.0 | 10 | 50.0 | 20 | 33.3 | |

| hCG ≥ 1500 | 14 | 35.0 | 26 | 65.0 | 40 | 66.7 | |

| Registration hCG (mIU/mL) at least 5000 | 0. 29 | ||||||

| hCG < 5000 | 14 | 46.7 | 16 | 53.3 | 30 | 50.0 | |

| hCG ≥ 5000 | 10 | 33.3 | 20 | 66.7 | 30 | 50.0 | |

| Age Group | 0.07 | ||||||

| 10–19 | 1 | 25.0 | 3 | 75.0 | 4 | 6.7 | |

| 20–29 | 5 | 23.8 | 16 | 76.2 | 21 | 35.0 | |

| 30–39 | 17 | 58.6 | 12 | 41.4 | 29 | 48.3 | |

| 40–49 | 1 | 25.0 | 3 | 75.0 | 4 | 6.7 | |

| 50–59 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 3.3 | |

for tests of no difference in proportion with surgical cure outcome

When the WHO risk score was ≤ 4, cure was observed in 24/55 (43.6%) and when the risk score was 5 or 6 no patients were cured (0/5). (Table 3)

When the outcomes and ultrasound findings were compared, if no evidence of residual uterine disease was observed 7 of 17 (41%) patients had a surgical cure and, if disease was seen but no myometrial invasion was reported, the response was classified as surgical cure in 9/22 (41%). For patients with myometrial invasion, including the two patients who had a surgical response, the combined response was seen in 10/21 (48%). (Table 3)

Uterine tumor size was recorded for all but one patient (2%). Thirty-five women (59%) had a residual intrauterine tumor large enough to be seen on pelvic ultrasound (>6 mm). The volume of disease in 3 dimensions was obtained for all 35 women for whom residual uterine disease was observed. Myometrial invasion was not universally reported; for 38 patients (64%) specific reference to myometrial depth was absent but in almost all cases could be inferred from the radiologist’s narrative. These ultrasound findings were not statistically or clinically significant.

If the registration hCG level was between 100 and 1500 mIU/mL then surgical cure was reported in 53% (10/19), when it was between 1,500 and 5,000 mIU/mL surgical cure was observed in 40% (4/10), between 5,000 and 10,000 mIU/mL in 29% (2/7), between 10,000 and 100,000 mIU/mL in 40% (8/20) and above 100,000 mIU/mL no cures (0/3) were observed. There was one additional surgical response between 1,500 and 5,000 mIU/mL and one more response at a level >100,000 mIU/mL, but these patients could not be included as surgical cures because they did not complete the 6-month follow-up. (Table 3)

Several hCG cutoff levels reported in the literature were examined using the study data set. Below 700 mIU/mL, 43% (6/14) were cured and above 700 mIU 43.9% (20/46) were cured.6 When a 1,500 mIU/mL cutoff was used, below that level 50% (10/20) were cured and above 1,500 mIU/mL, 40% (16/40) were cured.5 When the level from the Charing Cross report was examined, below 5,000 mIU/ml, 50% (15/30) were cured while above, 37% (11/30) were cured.24 None of these factors were found to be statistically significantly associated with outcome (Table 3).

The degree to which hCG level might predict response to second curettage was examined using a receiver operator characteristic plot (ROC curve).23 When the data from the current study was examined using the registration log-transformed hCG level, the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.59 suggesting that the hCG level at registration alone was a poor discriminator of surgical cure. A logistic model with age and squared age terms was fit to predict cure. The AUC for this model was 0.77 suggesting that a moderate association exists between these 2 parameters.

Three patients (3/60) were found to have placental site trophoblastic tumor at the second curettage and were automatically classified as surgical failures. However, the hCG level normalized in one of these patients without further treatment. One patient underwent hysterectomy and the other was treated successfully with methotrexate and subsequently had a successful pregnancy.

Data on toxicity was collected prospectively. There was infrequent and generally low-grade toxicity reported including one patient with grade 3 uterine hemorrhages (defined as requiring transfusion) and one case of grade 3 neutropenia. One uterine perforation was reported that was successfully managed by observation. (Table 4)

Table 4.

Grade of Adverse Event using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events 3.0

| Number of Patients with Maximum Adverse Event Grade |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event Term | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Fatigue | 57 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Hair loss/alopecia (scalp or body) | 59 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 58 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 59 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Perforation, uterus | 59 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hemorrhage, uterus | 59 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hemorrhage, vagina | 56 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Leukocytes | 59 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hemoglobin | 50 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| Platelets | 58 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Neutrophils | 59 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hypokalemia | 59 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperglycemia | 59 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypocalcemia | 58 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain: abdominal pain NOS | 55 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Pain: head/headache | 58 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Pain: chest wall | 59 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain: breast | 59 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Maximum Grade Overall | 43 | 9 | 6 | 2 |

In total, 29 of the original cohort of 64 women (45%) derived clinical benefit from the second curettage: 24 surgical cures, 2 surgical responses and 3 instances of a pathology change to Placental Site Trophoblastic tumor that was identified by second curettage earlier than likely would have otherwise been the case.

Discussion

This study demonstrates significant utility of second curettage as first-line treatment for persistent trophoblastic neoplasia. As a multicenter, prospective clinical trial it greatly strengthens the evidence that women with post-molar GTN can be treated safely and effectively with uterine curettage allowing 28 of 60 patients (47%) of trial participants to avoid chemotherapy. Three prior reports had suggested that between 9 and 60% of patients who undergo second curettage for persistent GTN might be saved the need for chemotherapy.5,6,8,24 This Gynecologic Oncology Group clinical trial represents the only prospective cooperative group study of this important issue.

Limitations of this Gynecologic Oncology Group study are primarily based on the patient numbers and the lack of standardization that arises in multi-institution trials. With only 60 evaluable patients this study has limited statistical power to discern the impact of well recognized prognostic factors such as age and hCG level on treatment effect. Furthermore the lack of standardization across institutions for the technique for second uterine curettage, with or without ultrasound guidance, prevents comment on ideal curettage technique.

In trophoblastic disease treatment centers around the world, second uterine curettage is viewed with mixed opinion. It has mostly been used to “debulk” residual intra-uterine disease or to control excessive vaginal bleeding in patients with newly diagnosed disease. The theoretical risk of uterine hemorrhage, upper genital tract infection or uterine perforation, is often cited as a reason to avoid curettage; despite that there were no surgical complications that required hysterectomy reported in the Sheffield and Netherland studies. In these previous studies, uterine perforation and grade 3 uterine hemorrhage were reported infrequently and were managed non-surgically.5,6 Delaying chemotherapy could theoretically lead to disease progression requiring multi-agent chemotherapy, this did not occur in this trial.

The present study demonstrated that the success of second curettage could not be predicted with statistical significance on the basis of patient age, the WHO risk score, registration hCG level or the ultrasound findings (the size or volume of intra-uterine disease and the depth of myometrial invasion). The extremes of patient age may have value in predicting failure although the numbers are too small to be conclusive. Only 1/4 patients aged 19 and under were cured or responded and 1/6 patients aged 40 or older were cured or responded. A model with age and squared age predicted cure with a receiver operator curve area under the curve of 0.77 suggesting a moderate association.

When the WHO risk score was 0–4, 24/55 patients (44%) were cured and there was one additional surgical response. Of the five patients with a score of 5 or 6, none were cured but one additional patient did have a surgical response, this trend was not statistically significant in exploratory analysis p=0.06. These findings suggest that second curettage is unlikely to benefit patients with a risk score of 5 or 6. No clinically significant complications related to the repeat curettage were observed. The likelihood of uterine perforation was very low and was managed conservatively. The prior reports from Sheffield and the Netherlands both reported an incidence of uterine perforation < 2% even though most of the second curettages in these reports were performed in a wide range of settings ranging from referral centers to community hospitals.14,15

Pelvic inflammatory disease was not observed in the current study and was not reported in the earlier reports. Hemorrhage after curettage was not clinically significant in any of the reports, including the present study. As a result, second curettage for GTN should be considered a low-risk intervention although longitudinal data on the incidence of uterine synechiae and infertility does not exist. While outcomes in this trial indicate second curettage is a low risk procedure they reflect the results when performed by physician’s expert in the care of GTN.

Based on central pathology review, in the present study, three patients were found to have placental-site trophoblastic tumor in the second curettage material confirming the Sheffield group’s observation (histo-conversion to choriocarcinoma in 5/544 women). The findings of central pathology review suggest that pathology expertise in interpretation of trophoblastic neoplasia is critical in this patient population. One additional patient had a placental nodule, a benign variant of epithelioid trophoblastic tumor at second curettage. Since these pathology changes were not identified until the post hoc central pathology review, the 3 women with placental site trophoblastic tumor were treated for presumed GTN. All were cured; 1 was cured by the repeat curettage alone, 1 women underwent second curettage followed by methotrexate and was cured while a third woman underwent hysterectomy and was cured.

Second curettage is a simple alternative to immediate chemotherapy for patients with newly diagnosed, non-metastatic, low risk GTN regardless of hCG level and the amount of intra-uterine disease25. Immediate chemotherapy may be preferred for patients with a WHO risk score of 5 or 6 and for patients at the extremes of reproductive life, specifically, ≤ 19 and > 39 years of age. In this study, 47% of patients derived potential benefit from immediate second curettage and were saved the need for chemotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Table 5.

World Health Organization Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia Prognostic Scoring System15

| Scores | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <40 | ≥40 | — | — |

| Antecedent pregnancy | Mole | Abortion | Term | — |

| Interval months from index pregnancy | <4 | 4–6 | 7–12 | >12 |

| Pretreatment serum β-hCG (iu/1) | <103 | 103–104 | 104–105 | >105 |

| Largest tumor size (including uterus) | <3 | 3–4 cm | ≥5 cm | — |

| Site of metastases | Lung | Spleen, kidney | Gastrointestinal | Liver, brain |

| Number of metastases | — | 1–4 | 5–8 | >8 |

| Previous failed chemotherapy | — | — | Single drug | ≥2 drugs |

Low-risk: individuals with a score ≤6

High-risk: individuals with a score ≥7

Reprinted from FIGO Oncology Committee. FIGO staging for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia 2000. FIGO Oncology Committee. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002 Jun;77(3):285–7, with permission from Elsevier.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Cancer Institute grants to the Gynecologic Oncology Group Administrative Office (CA 27469), the Gynecologic Oncology Group Statistical and Data Center (CA 37517), the NRG Oncology SDMC grant U10 CA180822 and the NRG Oncology Operations grant U10CA 180868.

Footnotes

For a list of acknowledgments, see Appendix 1 online at http://links.lww.com/xxx.

Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov,; https://clinicaltrials.gov/, NCT00521118.

References

- 1.Berkowitz R, Desai U, Goldstein D, Driscoll S, Marean A, Bernstein M. Pretreatment curettage; a predictor of chemotherapy response in gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 1980;10:39–43. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(80)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lao T, Lee F, Yeung S. Repeat curettage after evacuation of hydatidiform mole. An appraisal. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1987;66:305–307. doi: 10.3109/00016348709103641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flam F, Lundstrom V. The value of endometrial curettage in the follow-up of hydatidiform mole. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1988;67:649–651. doi: 10.3109/00016348809004280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlaerth J, Morrow C, Rodriguez M. Diagnostic and therapeutic curettage in gestational trophoblastic disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:1465–1470. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90907-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorigan P, Coleman J, Ng P, Coleman R, Hancock B. The role of second dilation and curettage in trophoblastic disease and the incidence of pregnancy in the first year after diagnosis. Brit J Cancer. 1996;73(Suppl XXVI):17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tidy J, Gillespie A, Bright N, Radstone C, Coleman R, Hancock B. Gestational trophoblastic disease: a study of mode of evacuation and subsequent need for treatment with chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:309–312. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soper J. Role of surgery and radiation therapy in the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Best Pract Res, Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;17:943–957. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6934(03)00091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pezeshki M, Hancock B, Silcocks P, et al. The role of repeat uterine evacuation in the management of persistent gestational trophoblastic disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Trommel N, Massugar L, Verheijen R, et al. The curative effect of a second curettage in persistent trophoblastic disease: A retrospective cohort survey. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garner E, Feltmate C, Goldstein D, Berkowitz R. The curative effect of a second curettage in persistent trophoblastic disease: a retrospective cohort survey. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yarandi F, Jafari F, Izadi-Mood N, Shojaei H. Clinical response to a second uterine curettage in patients with low-risk gestational trophoblastic disease. J Reprod Med. 2014;59:566–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osborne R, Filiaci V, Schink J, et al. Phase III trial of weekly methotrexate or pulsed dactinomycin for low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study #174) J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:825–831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.4386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotmensch S, Cole L. False diagnosis and needless therapy of presumed malignant disease in women with false-positive human chorionic gonadotropin concentrations. Lancet. 2000;355(9205):712–715. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)01324-6. 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas C, Segers M, Houx P. Comparison of the analytical characteristics and clinical usefulness in tumour monitoring of fifteen hCG(-beta) immunoassay kits. Am Clin Biochem. 1985;22:236–246. doi: 10.1177/000456328502200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.FIGO Oncology Committee. FIGO staging for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia 2000. Int J Gynaecol Oncol. 2002;77:285–287. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hancock B. Staging and classification of gestational trophoblastic disease. Best Pract Res, Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;17:869–883. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6934(03)00073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alazzam M, Tidy J, Osborne R, Coleman R, Hancock B, Lawrie T. The Cochrane Collaboration. London: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. Chemotherapy for resistant or recurrent gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: Cochrane Systematic Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerkmeijer L, Wielsma S, Massuger L, Sweep F, Thomas C. Recurrent gestational trophoblastic disease after hCG normalization following hydatidiform mole in The Netherlands. Gynecol Oncol. 2007 Jul;106(1):142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfberg A, ltmate C, Goldstein D, Berkowitz R, Lieberman E. Low risk of relapse after achieving undetectable hCG levels in women with complete molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:551–554. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000136099.21216.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen T, Ng T. Optimal flexible designs in phase II clinical trials. Stat Med. 1998;17:2301–2312. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981030)17:20<2301::aid-sim927>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkinson E, Brown B. Confidence limits for probability of response in multi-stage phase II clinical trials. Biometrics. 1985;41:741–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clopper C, Pearson E. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrica. 1934;26:404–413. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanley J, McNeil B. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGrath S, Short D, Harvey R, Schmid P, Savage P, Seckl M. The management and outcome of women with post-hydatidiform mole “low-risk” gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, but hCG levels in excess of 100,000 IUI−1. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:810–814. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reade C, Osborne R, Shah N, et al. Treatment of low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: a probabilistic decision analysis model. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130:e27–e28. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lybol C, Sweep F, Harvey R, et al. Relapse rates after two versus three consolidation courses of methotrexate in the treatment of low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:576–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.