Abstract

Purpose

In 1997, Vogelzang et al. reported that 61 % of patients with cancer indicated fatigue impacted daily life more than pain, and only 37 % of oncologists shared this perception. We provide an update to this study, which can help prioritize symptom assessment and management in the clinic. Study aims were to determine and compare perceptions of patients with cancer and health care providers (HCPs) of the impact of fatigue and pain.

Methods

A random sample of patients with cancer was recruited in the USA by Harris Poll Online and Schlesinger Associates. Oncology HCPs were recruited by Food and Drug Research, Inc. and Toluna, Inc.

Results

From June to November 2012, 550 of 1122 eligible patients (49 %), 400 of 533 eligible oncologists (75 %), and 400 of 617 eligible oncology nurses (65 %) completed a survey. Of patients, 58 % reported that fatigue affected their daily lives more than pain while undergoing treatment with chemotherapy versus 29 % of oncologists and 25 % of oncology nurses that had this perception. Ninety-eight percent of patients reported experiencing fatigue, whereas 72 % of oncologists and 84 % of oncology nurses thought this was the case. Eighty-six percent of patients reported pain while undergoing treatment with chemotherapy, whereas 36 % of oncologists and 51 % of oncology nurses believed this occurred. Nausea and vomiting felt by HCPs were the most concerning symptoms for patients (88 %).

Conclusions

This study shows the importance of assessing symptoms by direct patient report during chemotherapy treatment. HCPs continue to underestimate the prevalence and importance of fatigue and pain for patients with cancer, a finding that may alter the management of treatment-related symptoms and may influence the development of patient symptom management plans.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00520-016-3275-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Fatigue, Pain, Neoplasms, Drug therapy

Introduction

Fatigue is a common problem among people with cancer. It is associated with the disease itself and many of its treatments. The estimated prevalence of fatigue among patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy ranges from 17 to 82 % [1–3]. Fatigue has a significant adverse impact on daily activities and is one of the primary drivers of poor quality of life (QOL) [4–6]. Information about patient and health care provider (HCP) perceptions regarding the importance of fatigue in cancer is lacking.

In 1997, Vogelzang et al. reported that 61 % of patients with cancer indicated fatigue impacted daily life more than pain, whereas only 37 % of oncologists shared this perception [7]. Other more recent studies have continued to demonstrate a poor correlation between clinician and patient-reported subjective symptoms such as fatigue and pain [8, 9]. Pain management has also been shown to be inadequate in up to 1/3 of patients with solid tumors [10].

The importance of assessing patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in routine clinical practice and the integration of PROs with electronic health records to improve outcomes has recently been shown in a number of studies [11–13]. Efforts to standardize collection of PROs in electronic health records and recommendations for the multidisciplinary clinical management team to act on information gathered from PRO assessments have also been proposed [14, 15]. Underscoring the importance of PROs in the regulatory landscape, the US FDA has provided guidance for the collection of PRO endpoints in clinical trials, and the European Medicines Agency recently highlighted the value of PROs in developing therapies for patients with cancer [16, 17].

With recent changes in the management of cancer, longer life expectancy, and a heightened awareness of supportive care issues, an updated analysis to evaluate the current prevalence and perception of fatigue in current oncology practice was needed. We aimed to determine whether HCP awareness of the substantial impact of fatigue on the lives of patients with cancer has led to a decrease in its prevalence. We also aimed to compare perspectives on fatigue to similar perspectives on pain in cancer. Given what has been reported by various authors over the last two decades, we aimed to determine whether HCP perceptions of the impact of fatigue relative to pain on patients with cancer and treated with chemotherapy are more closely aligned with patient reports than has been historically observed [7–10].

Objectives

The primary objective of this study was to estimate the proportion of patients with cancer who report that fatigue affected their daily life more than pain while undergoing chemotherapy and to compare this proportion to that of providers (oncologists and oncology nurses) who were asked a similar question.

Secondary objectives were to estimate the prevalence of fatigue and pain among patients treated with chemotherapy, to determine provider estimated proportions of fatigue and pain among their patients receiving chemotherapy, and to compare the patient-reported prevalence and provider-reported estimated proportions of fatigue and pain.

Methods

A sample of patients from the general US population was recruited via email by online survey firms Harris Poll Online and Schlesinger Associates. Oncology HCPs practicing in the USA were recruited via email by Food and Drug Research, Inc. and Toluna, Inc. Data consisted of patient-reported demographic, disease, treatment characteristics, and survey responses from patients with cancer and oncology HCPs. Quorum Review Institutional Review Board granted an exception to the formal informed consent process because the survey did not capture any patient identifying information.

Statistical analyses

This was an estimation study; no formal hypothesis testing was planned. Proportions of patients and HCP perceptions were estimated for fatigue affecting daily life more than pain, pain affecting daily life more than fatigue, experiencing fatigue, and experiencing pain. Differences between patients and HCPs perceptions were computed.

Patient eligibility criteria

To be eligible to participate, patients had to be age 18 or older, have a diagnosis of a non-hematologic tumor, have received at least 2 months of chemotherapy and/or targeted/biologic therapy initiated less than 14 months before the date of survey initiation, and received chemotherapy within 1 year of participation in the survey. Exclusion criteria included a history of myelodysplastic syndrome or hematologic malignancy such as leukemia, lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease, or multiple myeloma; having received a bone marrow or stem cell transplant at any time; and having participated in a previous survey of any kind within the last 3 months. Patients were also excluded if they resided outside the USA or if they received the last dose of chemotherapy more than 1 year from the date of survey completion.

HCP eligibility criteria

To be eligible, oncologists and oncology nurses had to have spent at least 75 % of their work time in patient care and at least 50 % of their work time providing direct care for adult patients with solid tumors receiving chemotherapy. Oncologists were required to be currently employed ≥30 h/week as a medical oncologist, hematologist/oncologist, or gynecologic oncologist and in practice for 2 years or more after completing fellowship. Oncology nurses were required to be currently employed ≥30 h/week as a registered nurse or nurse practitioner and to have cared for at least 100 patients with solid tumors receiving chemotherapy in the past 2 years. Exclusion criteria included primary practice in hematology, radiation oncology, or surgical oncology.

Results

Patient baseline demographics and disease characteristics

From June to November 2012, 550 of 1122 eligible patients (49 %) completed a survey (Appendix). Of these, 144 (26 %) were men, 406 (74 %) were women; median (minimum, maximum) age for all patients was 58 (19, 91) years; 171 (31 %) patients were ≥65 years of age; and self-rated Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status was 0 or 1 for 41 % of patients, 2 for 31 % of patients, and ≥3 for 27 % of patients. Patient-reported most recently diagnosed cancer (number [%]) included breast (212 [39]), lung (74 [14]), colon (47 [9]), ovarian (44 [8]), prostate (30 [6]), uterine (16 [3]), liver (15 [3]), brain (13 [2]), bladder (12 [2]), and rectal (12 [2]). Metastatic and/or stage 4 disease was reported by 235 (43 %) patients. Five hundred twenty-four patients (95 %) had received or were currently receiving chemotherapy, while 147 (27 %) patients had received or were currently receiving targeted or biologic therapy. More than half of patients (298 [54 %]) had received or were currently receiving radiation, and 121 (22 %) had received or were currently receiving hormonal therapy. Most patients (458 [83 %]) had received the last dose of chemotherapy or targeted/biologic therapy within the previous 6 months, and more than half of patients (293 [53 %]) were receiving some type of therapy at the time of the survey (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics

| Overall (N = 550) | |

|---|---|

| Sex—n (%) | |

| Male | 144 (26.2) |

| Female | 406 (73.8) |

| Race—n (%) | |

| White | 477 (86.7) |

| Black or African American | 45 (8.2) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 4 (0.7) |

| Asian | 7 (1.3) |

| Some other race | 16 (2.9) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.2) |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin—n (%) | |

| No, not of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin | 525 (95.5) |

| Mexican, Mexican American, Chicano | 6 (1.1) |

| Cuban | 2 (0.4) |

| Another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin | 15 (2.7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (0.4) |

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 58.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 49.0, 66.0 |

| Min, max | 19, 91 |

| Age group—n (%) | |

| ≤50 | 150 (27.3) |

| 51–64 | 229 (41.6) |

| 65–74 | 131 (23.8) |

| ≥75 | 40 (7.3) |

| Most recently diagnosed cancer—n (%) | |

| Breast | 212 (38.5) |

| Genitourinary | 51 (9.3) |

| Lung | 74 (13.5) |

| Gastrointestinal | 98 (17.8) |

| Gynecologic | 69 (12.5) |

| Other | 46 (8.4) |

| Duration from cancer diagnosis (years) | |

| Median | 1.7 |

| Q1, Q3 | 0.8, 4.7 |

| Min, max | 0, 51 |

| Cancer treatment—n (%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 524 (95.3) |

| Radiation therapy | 298 (54.2) |

| Hormonal therapy | 121 (22.0) |

| Targeted therapy or biologic therapy | 147 (26.7) |

| Completed most recent chemotherapy or targeted/biologic therapy—n (%) | |

| Currently being treated | 293 (53.3) |

| 0–3 months ago | 99 (18.0) |

| 4–6 months ago | 66 (12.0) |

| 7–9 months ago | 33 (6.0) |

| 10–12 months ago | 59 (10.7) |

| ECOG performance status—n (%) | |

| 0: normal activity, without symptoms | 30 (5.5) |

| 1: some symptoms but do not require bed rest during waking day | 198 (36.0) |

| 2: require bed rest for less than 50 % of waking day | 173 (31.5) |

| 3: require bed rest for more than 50 % of waking day | 135 (24.5) |

| 4: unable to get out of bed | 14 (2.5) |

HCP baseline demographics

From June to November 2012, 400 of 533 eligible oncologists (75 %) and 400 of 617 eligible oncology nurses (65 %) completed a survey (Appendix). The median number of years in oncology practice was 15 years, with a minimum of 2 and a maximum of 45 years. Most were single specialty group practices (40.5 %), followed by academic or teaching hospitals (19.4 %), and multiple specialty private group practices (17.3 %). Community-based hospital and solo practices accounted for 15.4 and 7.5 % of practices, respectively. Patients with lung, breast, colorectal, prostate, ovarian, lymphoma, leukemia, as well as other cancers were treated at these practices (Table 2).

Table 2.

HCP practice demographics

| Overall (N = 800) | |

|---|---|

| Number of years in oncology practice | |

| Median | 15.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 10.0, 23.0 |

| Min, max | 2, 45 |

| Type of practice—n (%) | |

| Academic | 155 (19.4) |

| Community | 123 (15.4) |

| Multiple specialty private group | 138 (17.3) |

| Single specialty group | 324 (40.5) |

| Solo | 60 (7.5) |

| Type of patients—% | |

| Lung cancer | |

| Median | 20.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 15.0, 25.0 |

| Breast cancer | |

| Median | 25.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 20.0, 30.0 |

| Colorectal cancer | |

| Median | 19.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 15.0, 20.0 |

| Prostate cancer | |

| Median | 10.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 5.0, 15.0 |

| Ovarian cancer | |

| Median | 5.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 2.0, 10.0 |

| Lymphoma | |

| Median | 10.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 5.0, 15.0 |

| Leukemia | |

| Median | 5.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 2.0, 10.0 |

| Other | |

| Median | 0.0 |

| Q1, Q3 | 0.0, 3.0 |

Primary endpoint

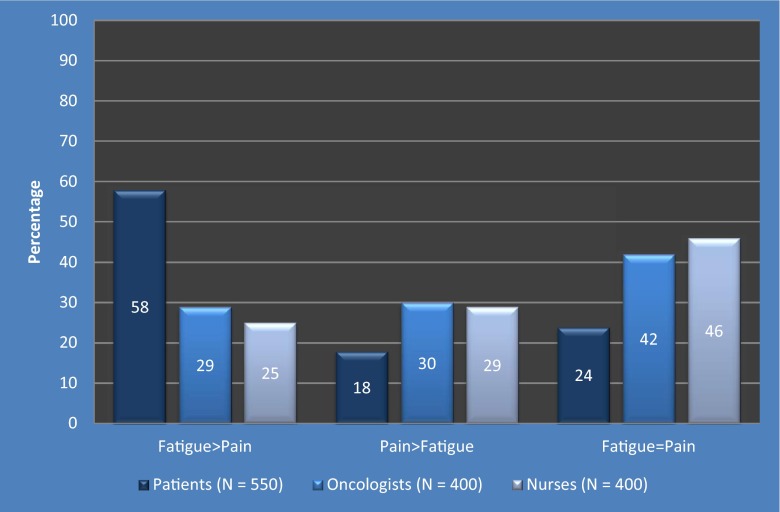

The majority (58 %) of patients reported that fatigue had a greater impact than pain on their daily lives while undergoing treatment with chemotherapy, whereas 29 % of oncologists and 25 % of nurses had this perception (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Perception of the impact of fatigue and pain on daily life during chemotherapy

Secondary endpoints

About one fifth (18 %) of patients reported that pain had a greater impact than fatigue on their daily lives while undergoing treatment with chemotherapy, whereas 30 % of oncologists and 29 % of nurses had this perception. The perception that fatigue and pain had an equal impact on daily life was reported by 24 % of patients, 42 % of oncologists, and 46 % of nurses (Fig. 1).

Nearly all patients (536 of 550; 97.5 %) reported that they experienced some degree of fatigue while undergoing treatment with chemotherapy. HCPs asked to estimate the proportion of patients that experienced fatigue during chemotherapy reported that 77.9 % of patients experienced fatigue overall, an underestimate of 20 % (95 % CI, 18 %, 21 %). Most patients (474 of 550; 86.2 %) also experienced pain while undergoing treatment with chemotherapy. HCPs asked to estimate the proportion of patients that experienced pain during chemotherapy reported that 43.6 % of patients experienced pain overall, an underestimate of 43 % (95 % CI, 39 %, 46 %).

On scales of 0 to 10, where 0 represented no fatigue and 10 represented the most severe fatigue, the mean (standard deviation [SD]) fatigue severity score reported by patients was 7.0 (2.6) and the mean (SD) pain severity score was 5.2 (3.3). The survey results demonstrated that nausea and vomiting were the side effects that 88 % of HCPs felt most concerned patients, and nausea/vomiting were the side effects from chemotherapy that most health care providers (97 %) reported typically documenting in the patient chart during chemotherapy treatment.

Ad hoc subset analyses were performed on categories by tumor type, ECOG performance status score, gender, metastatic disease status, and time since diagnosis (Table 3). For all tumor types combined, more patients reported fatigue than pain during cancer treatment (98 vs 86 %). Fatigue ranged from 91.3 % in other tumor types to 100 % for gynecologic and lung tumors; the range for pain was 74.5 % for gastrointestinal tumors to 97.1 % for gynecologic tumors. In patients with ECOG performance status scores of 0 and 1, 15 of 30 (50 %) and 37 of 198 (18.7 %) patients reported no pain, whereas fatigue was reported by 70 and 98 %, respectively. Nearly all patients with ECOG performance status of 1 to 4 reported experiencing fatigue. Time since diagnosis did not appear to impact reporting of pain or fatigue.

Table 3.

Patient-reported fatigue and pain severity scores

| Experiencing fatigue (score > 0)—n (%) | Not experiencing fatigue (score = 0)—n (%) | Experiencing pain (score > 0)—n (%) | Not experiencing pain (score = 0)—n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 550) | 536 (97.5) | 14 (2.5) | 474 (86.2) | 76 (13.8) |

| By tumor type | ||||

| Breast (n = 212) | 207 (97.6) | 5 (2.4) | 182 (85.8) | 30 (14.2) |

| Genitourinary (n = 51) | 48 (94.1) | 3 (5.9) | 47 (92.2) | 4 (7.8) |

| Lung (n = 74) | 74 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 64 (86.5) | 10 (13.5) |

| Gastrointestinal (n = 98) | 96 (98.0) | 2 (2.0) | 73 (74.5) | 25 (25.5) |

| Gynecologic (n = 69) | 69 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 67 (97.1) | 2 (2.9) |

| Other (n = 46) | 42 (91.3) | 4 (8.7) | 41 (89.1) | 5 (10.9) |

| By ECOG performance status | ||||

| 0 (n = 30) | 21 (70.0) | 9 (30.0) | 15 (50) | 15 (50) |

| 1 (n = 198) | 194 (98.0) | 4 (2.0) | 161 (81.3) | 37 (18.7) |

| 2 (n = 173) | 172 (99.4) | 1 (0.6) | 159 (91.9) | 14 (8.1) |

| 3 (n = 135) | 135 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 126 (93.3) | 9 (6.7) |

| 4 (n = 14) | 14 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 13 (92.9) | 1 (7.1) |

| By gender | ||||

| Male (n = 144) | 139 (96.5) | 5 (3.5) | 123 (85.4) | 21 (14.6) |

| Female (n = 406) | 397 (97.8) | 9 (2.2) | 351 (86.5) | 55 (13.5) |

| By metastatic disease status | ||||

| Yes (n = 235) | 234 (99.6) | 1 (0.4) | 207 (88.1) | 28 (11.9) |

| No (n = 315) | 302 (95.9) | 13 (4.1) | 267 (84.8) | 48 (15.2) |

| By time since diagnosis | ||||

| ≤1 year (n = 184) | 182 (98.9) | 2 (1.1) | 157 (85.3) | 27 (14.7) |

| >1 and ≤3 years (n = 170) | 164 (96.5) | 6 (3.5) | 149 (87.6) | 21 (12.4) |

| >3 and ≤5 years (n = 66) | 65 (98.5) | 1 (1.5) | 51 (77.3) | 15 (22.7) |

| >5 years (n = 130) | 125 (96.2) | 5 (3.8) | 117 (90.0) | 13 (10.0) |

Discussion

This study emphasizes the importance of assessing symptoms by direct patient report while undergoing treatment with chemotherapy. There continues to be a gap between HCPs and patients in the relative emphasis placed on fatigue versus pain. In 1997, Vogelzang et al. reported a 24 % difference between patients (61 %) and oncologists (37 %) of the perception that fatigue impacted daily life more than pain [7]. Our study showed a 29 % difference between patients (58 %) and oncologists (29 %) and a 33 % difference between patients and oncology nurses (25 %) of the perception that fatigue impacted daily life more than pain. Clearly, there remains a discrepancy between patients and HCPs regarding the relative importance of fatigue versus pain while undergoing treatment with chemotherapy; pain is a symptom that may be more readily monitored, tracked, and treated than fatigue for HCPs in the clinic. Efforts to educate patients of the importance of fatigue as a symptom of chemotherapy that should be recognized and treated should continue, and educational programs for multidisciplinary oncology teams should include components that focus on fatigue symptom information gathering. Factors that contribute to fatigue, such as anemia due to myelosuppression, anemia due to dehydration, or sleep disturbances, should also be considered by HCPs.

Fatigue can be both a manifestation of cancer treatment, as well as a symptom attributable to the cancer itself, which may lead to misattribution of fatigue symptoms and the impact of these symptoms on patient functioning. Furthermore, estimates of fatigue among patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy vary widely in the literature, ranging from 17 to 82 %, which may further explain the gap in the awareness of fatigue between HCPs and patients [1–3]. While we did not examine whether patients were participating in an exercise or rehabilitation program, exercise has emerged as an effective treatment for fatigue in patients with cancer [18].

Patient-reported and HCP perceptions of the impact of pain on daily life also showed differences between patients and HCPs. Thirty percent of oncologists and 29 % of oncology nurses believed that pain had a greater impact than fatigue on daily life while undergoing treatment with chemotherapy, compared with only 18 % of patients that reported this perception. Compared with fatigue, pain may be better controlled among chemotherapy patients due to the effectiveness of pain management plans in patients with cancer. Furthermore, the differential between HCP and patient perceptions of the impact of pain on daily life may lead HCPs to treat pain more aggressively, leading to the decreased impact of pain relative to fatigue reported by patients.

Studies such as ours may lead to increased awareness of the need for the assessment of fatigue symptoms on an ongoing basis in patients with cancer in the clinic. In our study, 29 % of oncologists and 25 % of oncology nurses perceive that fatigue impacts daily life more than pain, whereas 58 % of patients have this perception. The capture of PROs through electronic medical records may facilitate discussions between patients and the multidisciplinary clinical management team, which may lead to increased recognition of and targeted treatment for subjective symptoms such as fatigue and pain. Management plans to increase HCP awareness of fatigue symptoms for patients at-risk of or experiencing fatigue, as well as educational programs to help patients and primary caregivers recognize fatigue symptoms, may be helpful in controlling symptoms of fatigue, thereby increasing quality of life in patients with cancer.

Potential biases and limitations

Given this study’s nonrandom sampling from an internet survey panel, selection bias may be a limitation since the respondent was on an email list and then self-selected to participate in the study. Selection bias may have also prevented patients from participating, particularly for less internet-literate patients. In addition, patients with lower income may have less access to internet services and may not have participated as frequently as patients with higher income [19].

Patients were asked in the survey (Appendix) to answer questions about “fatigue during your treatment with chemotherapy”; therefore, it is possible that the fatigue patients reported was due to their disease, rather than a side effect of chemotherapy. Measurement errors from patients can occur from the questions being misunderstood or from recall bias to the experiences during chemotherapy, potentially resulting in information bias. Historical publications mention that cancer patient survey responses could be affected by recall bias due to potential cognitive impairment related to chemotherapy.

Measures taken to minimize bias at the study design or analysis stage

At the study design level, a multiphase approach was implemented to minimize subject selection bias. One method to minimize bias was through a pretest feedback survey conducted with five each of patients, nurses, and physicians that were not enrolled onto the study. To minimize recall bias, eligibility criteria were set such that patients were excluded from the survey if they had been off chemotherapy >1 year, ensuring that the study sampled a population on or recently off chemotherapy, essentially limiting potential recall bias.

Generalizability of findings

The study findings may not be generalizable to the US population. Most patients reported that they were non-Hispanic and women (95.5 and 73.8 % respectively), whereas the US census bureau reports that Hispanics constituted 16.7 % of the nation’s total population, and as of 2011, 50.8 % were female (www.census.gov). Furthermore, the study findings may not be generalizable to the cancer population. For example, comparing patients in the current study to those included in the Oncology Services Comprehensive Electronic Records (OSCER) database, a larger proportion of study patients fall into the 45- to 55-year-old category (24 vs 17.6 %) and fewer fall into the >75-year range (7.3 vs 17.6 %). In this study, 38.5 % of patients had breast cancer, whereas 28.7 % of the OSCER database are women with breast cancer. Perhaps most importantly, the sample may be overrepresented by symptomatic patients, given the high proportion of people with ECOG performance status ≥2 [20]. Patients with decreased performance status were possibly experiencing more problems with pain and fatigue and may have been more likely to respond to the survey.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOC 173 kb)

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance for this manuscript was provided by James Ziobro on behalf of Amgen Inc. This study was funded by Amgen Inc.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Loretta A. Williams is a compensated consultant for Amgen, Inc. Chet Bohac is an employee of and owns stock in Amgen Inc. Sharon Hunter is a compensated contract worker for Amgen Inc. David Cella is a compensated consultant for Amgen, Inc.

References

- 1.Richardson A. Fatigue in cancer patients: a review of the literature. Eur J Cancer Care. 1995;4(1):20–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.1995.tb00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cella D, Davis K, Breitbart W, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: prevalence of proposed diagnostic criteria in a United States sample of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(14):3385–3391. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cella D, Lai JS, Chang CH, et al. Fatigue in cancer patients compared with fatigue in the general United States population. Cancer. 2002;94(2):528–538. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demetri GD, Kris M, Wade J, et al. Quality-of-life benefit in chemotherapy patients treated with epoetin alfa is independent of disease response or tumor type: results from a prospective community oncology study. Procrit Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(10):3412–3425. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.10.3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curt GA, Breitbart W, Cella D, et al. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: new findings from the fatigue coalition. Oncologist. 2000;5(5):353–360. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Littlewood TJ, Bajetta E, Nortier JW, et al. Effects of epoetin alfa on hematologic parameters and quality of life in cancer patients receiving nonplatinum chemotherapy: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2865–2874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vogelzang NJ, Breitbart W, Cella D, et al. Patient, caregiver, and oncologist perceptions of cancer-related fatigue: results of a tripart assessment survey. The fatigue coalition. Semin Hematol. 1997;34(3 Suppl 2):4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basch E, Iasonos A, McDonough T, et al. Patient versus clinician symptom reporting using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: results of a questionnaire-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(11):903–909. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70910-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fromme EK, Eilers KM, Mori M, et al. How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? A comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(17):3485–3490. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisch MJ, Lee JW, Weiss M, et al. Prospective, observational study of pain and analgesic prescribing in medical oncology outpatients with breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(16):1980–1988. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert A, Sebag-Montefiore D, Davidson S, et al. Use of patient-reported outcomes to measure symptoms and health related quality of life in the clinic. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(3):429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basch E. The rationale for collecting patient-reported symptoms during routine chemotherapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2014;2014:161–165. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett AV, Jensen RE, Basch E. Electronic patient-reported outcome systems in oncology clinical practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(5):337–347. doi: 10.3322/caac.21150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu AW, Kharrazi H, Boulware LE, et al. Measure once, cut twice—adding patient-reported outcome measures to the electronic health record for comparative effectiveness research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(8 Suppl):S12–S20. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes EF, Wu AW, Carducci MA, et al. What can I do? Recommendations for responding to issues identified by patient-reported outcomes assessments used in clinical practice. J Support Oncol. 2012;10(4):143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guidance for industry: patient reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labelling claims. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration, 2009. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. Accessed 13 Jan 2016.

- 17.Reflection paper on the use of patient reported outcomes (PRO) measures in oncology studies. London, United Kingdom: European Medicines Agency, 2014. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2014/06/WC500168852.pdf. Accessed 13 Jan 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Cramp F, Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD006145. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006145.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Couper M. Web surveys: a review of issues and approaches. Public Opin Q. 2000;64(4):464–494. doi: 10.1086/318641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paoli CJ, Bach BA, Quach D, et al. Performance status of real-world oncology patients before and after first course of chemotherapy. J Community Support Oncol. 2014;12:163–170. doi: 10.12788/jcso.0041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 173 kb)