Abstract

Background and study aims: Catheter-based radiofrequency ablation (RFA) delivered during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may represent a viable treatment option for intraductal extension of ampullary neoplasms, however, clinical experience with this modality is limited. After ampullary resection, 4 patients with intraductal extension underwent adjunctive RFA of the distal bile duct. All patients received a temporary pancreatic stent to reduce the risk of pancreatitis, as well as a plastic biliary stent to prevent biliary obstruction. Three patients were treated for adenoma and 1 for adenoma with a focus of adenocarcinoma. During a short follow-up period, 3 patients experienced complete eradication of the target lesion, whereas the patient with a focus of adenocarcinoma had progression to overt invasive cancer. There were no immediate adverse events. One patient developed a post-RFA bile duct stricture, which has required additional endoscopic therapy. Catheter-based RFA of ampullary lesions that extend up the bile duct is technically feasible. Additional research is necessary to understand the risks and long-term benefits of this technique.

Introduction

Catheter-based radiofrequency ablation (RFA) delivered during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has recently emerged as a possible therapeutic option within the bile duct 1 2 3 4. Intrabiliary extension of neoplasm remains an important challenge in the endoscopic eradication of complex ampullary lesions 5 6, and RFA may represent a viable treatment adjunct for this problem. Recently, the use of RFA at the ampulla and within the distal bile duct has been described 7 8. Herein we present 4 cases assessing the technical feasibility, safety, and treatment outcomes of RFA employed at the time of ERCP to treat ampullary lesions with intraductal extension.

Case Reports

The study was conducted at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) from July 1, 2014 through October 1, 2015. After institutional review board approval, we retrospectively identified eligible adult subjects through the MUSC endoscopy report database (Endoworks, Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) by searching for reports that contained the keywords “radiofrequency ablation (RFA)” and “endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)”. We excluded patients who underwent RFA of a stricture not associated with an ampullary lesion. We collected relevant clinical, histologic, and endoscopic data on all eligible subjects.

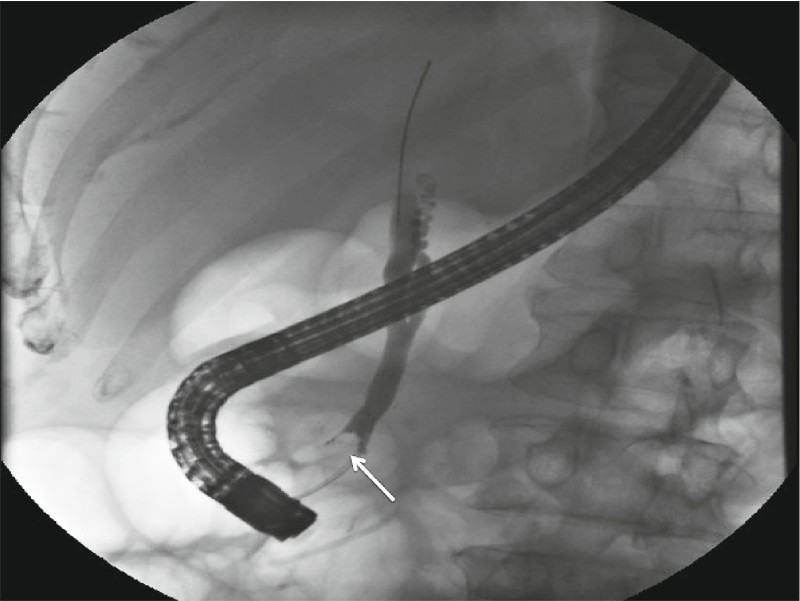

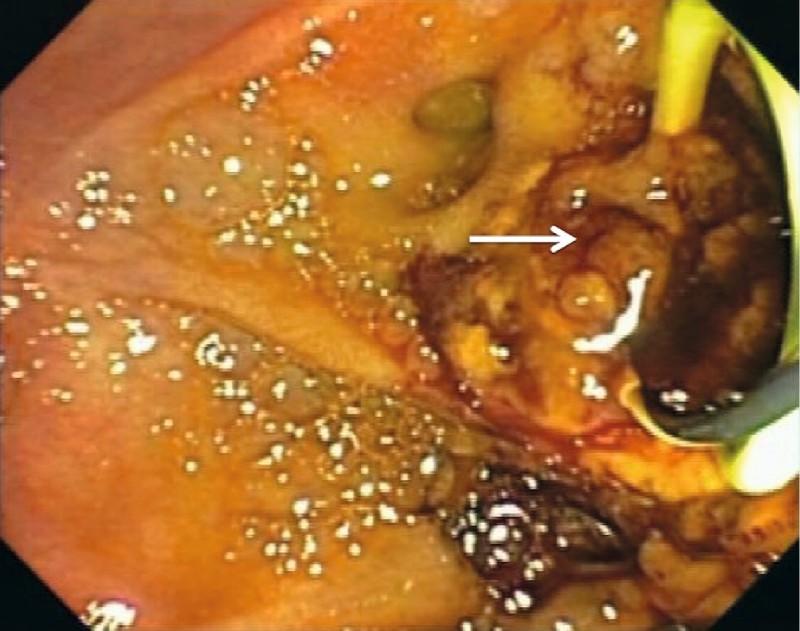

All procedures were performed by an experienced pancreaticobiliary endoscopist under general anesthesia using a side-viewing duodenoscope. Included patients had undergone histologic evaluation of their ampulla prior to treatment. Ampullary resection was performed either en bloc or in piecemeal fashion by delivering electrosurgical current through a snare with or without prior submucosal lift. Intraductal extension of the lesion was assessed cholangiographically (Fig. 1) and/or visually (Fig. 2). In some cases, a biliary sphincterotomy extension and papillary balloon dilation was performed to expose the inside of the terminal bile duct for assessment and therapy. Ablative therapy was delivered using a standard Argon Plasma Coagulation (APC) probe (ERBE USA Inc., Mariette, GA) at a flow rate of 1.0 L/min to 1.2 L/min and 30 to 40 maximum watts (W) and/or the Habib EndoHPB RFA bipolar cautery probe (EMcision United Kingdom, London, United Kingdom) at 10 W for 60 to 90 seconds, extrapolating from manufacturer’s recommendations of 7 to 10 W × 120 seconds 9. Given the proximity to the pancreatic orifice and the benign nature of the target lesions, a shorter duration of treatment was chosen. In general, APC was reserved for treating exposed target tissue in the duodenum or very distal duct, whereas RFA was reserved for treating hidden or difficult to access tissue within the duct. All patients undergoing RFA received a temporary pancreatic stent (5 Fr, 2 – 5 cm) and rectal indomethacin to reduce the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP), as well as a plastic endobiliary prostheses to prevent biliary obstruction and cholangitis.

Fig. 1.

Cholangiogram showing a filling defect in the distal bile duct (arrow) representing bulky intraductal extension of an ampullary adenoma.

Fig. 2.

Endoscopic view of the papilla after ampullectomy demonstrating intraductal extension of the adenoma (arrow).

Technical success was defined as the ability to successfully position the RFA probe across the biliary orifice and deliver thermal energy to the region of the papilla and terminal bile duct, resulting in coagulation of the visualized target areas. Clinical success was defined as endoscopic absence of polypoid or adenomatous-appearing tissue at the treatment site and histologic absence of neoplasm based on extensive follow-up biopsies from the papilla, pancreaticobiliary septum, biliary orifice, and distal bile duct. When the distal bile duct was not fully exposed by prior sphincterotomy, a pediatric biopsy forceps was introduced into the distal duct to acquire tissue. We intended to repeat RFA sessions until visual and histologic clearance was observed.

Patient demographics, procedure indications, and treatment outcomes are listed in Table 1. Four eligible patients were identified, all of whom were men with a mean age of 63 years (range 54 – 84). Three patients (75 %) had a history of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Three patients were treated for ampullary adenoma and 1 for ampullary adenoma with a focus of adenocarcinoma (he declined surgical evaluation).

Table 1. Characteristics and outcomes of included cases.

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Age | 54 | 84 | 54 | 58 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Male | Male |

| FAP | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Histology | Adenoma | Adenoma with HGD/IMC | Adenoma | Adenoma |

| Sphincterotomy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ampullectomy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| APC sessions | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| RFA sessions, mean sec (range) | 1, 80 | 3, 80 (70 – 90) | 1, 75 | 1, 80 |

| Follow up, days | 56 | 105 | 38 | 51 |

| Complications | No | No | Bile duct stricture | No |

| Treatment success | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Recurrence | No | Developed cancer | No | No |

FAP, familial adenomatous polyposis; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; IMC, intramucosal cancer; APC, argon plasma coagulation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; PEP, post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound

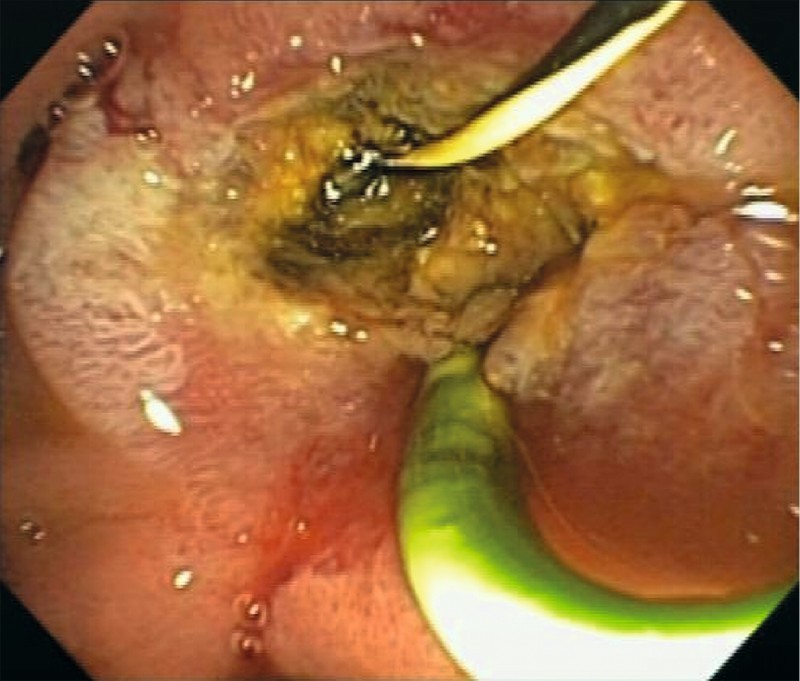

Video 1 presents a synopsis of 2 representative cases. All RFA procedures were technically successful, resulting in a perceptible tissue effect (Fig. 3). RFA was performed immediately following endoscopic resection in 1 case and during a subsequent session in the remaining cases. The mean number of RFA sessions per patient was 1.5 (range 1 – 3). All patients were discharged uneventfully after the procedure without any immediate adverse events (AEs). One patient developed obstructive jaundice due to a fibro-inflammatory bile duct stricture at the level of prior RFA that manifested 3 days after biliary stent removal (approximately 6 weeks after the RFA) and has required ongoing endobiliary stent therapy in excess of 3 months. No other AEs have been observed. During the follow-up period, 3 patients had visual and histologic evidence of complete eradication; the patient with a focus of adenocarcinoma who declined surgery developed overt invasive ampullary cancer.

Fig. 3.

Endoscopic view of the papilla after ampullectomy and intraductal radiofrequency ablation.

Video 1

This footage consists of 2 video clips demonstrating catheter-based RFA of intraductal ampullary adenoma.

Discussion

Although endoscopic ampullectomy is the preferred treatment for noninvasive ampullary lesions with a success rate reported as high as 92 % 10, biliary extension of neoplasm represents a significant obstacle to endoscopic eradication. Exposure and eversion of the adenoma through a biliary sphincterotomy to allow resection or ablation has been described in amenable cases 5 11 12. However, broad adenomatous involvement of the distal bile is associated with limited treatment success (< 50 %) and has been considered an indication for surgical resection 5. Based on its ease of use and the ability to precisely position the probe within the distal duct, radiofrequency ablation may represent the first viable treatment adjunct for this challenging scenario. To date, only single case reports of RFA for benign ampullary lesions have been described; we aimed to expand our understanding of this technology by presenting our experience in 5 patients.

Catheter-based RFA was technically successful in all cases, and based on short-term follow up in a small sample, may be safe and clinically effective. However, because RFA induces thermal injury and subsequent necrosis of the bile duct wall and beyond, several safety concerns exist. First, while RFA has been associated with a favorable safety profile when applied to malignant biliary strictures 1 2 3 4, it remains unclear whether RFA in the intra-pancreatic portion of the bile duct without the protective buffer of a surrounding tumor – especially in the vicinity of the pancreatic orifice – will be associated with an increased risk of pancreatitis. Until additional data on the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis in this context are available, prophylactic pancreatic stent placement seems reasonable. If the pancreatic and biliary orifices are in close proximity, especially if adenoma appears to involve the pancreaticobiliary septum, it may be best to perform the RFA adjacent to a guidewire which has already been placed in the pancreatic duct (subsequently guaranteeing pancreatic access for stent placement) rather than adjacent to a plastic pancreatic stent which may be damaged or even fractured during RFA.

Another safety concern is the development of clinically important post-RFA biliary strictures that occurred in 1 of our patients, akin to what has been observed in the esophagus after RFA of Barrett’s epithelium 13. This concern is particularly relevant in the context of benign ampullary disease in which patients do not typically undergo long-term stent placement, as is the case when RFA is performed for palliation of malignant strictures. Along these lines, until additional data are available, we have attempted to minimize RFA across the cystic duct takeoff to avoid thermal injury-related obstruction of the cystic duct, which has intentionally been induced by electrohydraulic lithotripsy to treat refractory bile leak 14.

In our series, RFA appears to have provided effective adjunctive therapy in all 4 cases of benign pathology but was ineffective in the setting of early adenocarcinoma, underscoring the concept that surgical resection remains first-line therapy for ampullary cancer (our patient declined surgery and chemoradiation). Despite the apparent effectiveness for benign lesions, it is important to consider that intrabiliary extension is often nodular in nature, leading to heterogeneous contact between the RFA probe and the target tissue; this may lead to incomplete therapy and/or an increased risk of buried neoplasm as is the concern when RFA is used to treat nodular Barrett’s esophagus. Moreover, it can be technically challenging to ensure circumferential contact of the probe and the target tissue within a dilated bile duct, even when luminal air is suctioned to induce collapse of the duct around the probe. In these cases, a balloon-based RFA device that flattens nodular tissue and maximizes treatment contact may be of value. An additional consideration is that the proximal extent of neoplasm is often difficult to assess cholangiographically and the role of cholangioscopy to guide probe placement should be further explored. Prospective studies are necessary to evaluate these issues and determine the long-term effectiveness of this modality.

In summary, catheter-based RFA after endoscopic resection of ampullary lesions that extend up the bile duct is technically feasible. Concerns regarding injury to the pancreas and bile duct as well as incomplete treatment of nodular target tissue exist and will be addressed by additional clinical experience and research.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None

References

- 1.Dolak W, Schreiber F, Schwaighofer H. et al. Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for malignant biliary obstruction: a nationwide retrospective study of 84 consecutive applications. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:854–860. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steel A W, Postgate A J, Khorsandi S. et al. Endoscopically applied radiofrequency ablation appears to be safe in the treatment of malignant biliary obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monga A, Gupta R, Ramchandani M. et al. Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation of cholangiocarcinoma: new palliative treatment modality (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:935–937. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tal A O, Vermehren J, Friedrich-Rust M. et al. Intraductal endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of hilar non-resectable malignant bile duct obstruction. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:13–19. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohnacker S, Seitz U, Nguyen D. et al. Endoscopic resection of benign tumors of the duodenal papilla without and with intraductal growth. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridtitid W, Tan D, Schmidt S E. et al. Endoscopic papillectomy: risk factors for incomplete resection and recurrence during long-term follow-up. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehendiratta V, Desilets D J. Use of radiofrequency ablation probe for eradication of residual adenoma after ampullectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1055–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valente R, Urban O, Del Chiaro M. et al. ERCP directed radio-frequency ablation (RFA) of an intra-pancreatic duct (PD) and intra-bile duct (BD) growing ampullary adenoma. A possible safe and mini invasive alternative to surgical treatment. Pancreatology. 2015;15:S98. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Itoi T, Isayama H, Sofuni A. et al. Evaluation of effects of a novel endoscopically applied radiofrequency ablation biliary catheter using an ex-vivo pig liver. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:543–547. doi: 10.1007/s00534-011-0465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catalano M F, Linder J D, Chak A. et al. Endoscopic management of adenoma of the major duodenal papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:225–232. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saleem A, Wang K K, Baron T H. Successful endoscopic treatment of intraductal extension of a villous adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, with 3-year follow-up. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:714–716. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim J H, Moon J H, Choi H J. et al. Endoscopic snare papillectomy by using a balloon catheter for an unexposed ampullary adenoma with intraductal extension (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1404–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaheen N J, Sharma P, Overholt B F. et al. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett's esophagus with dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2277–2288. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shahid H, Korenblit J, Kowalski T. et al. Novel application of electrohydraulic lithotripsy probe in managing a refractory cystic duct bile leak. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:744–745. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]