Abstract

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), especially cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective inhibitors, are among the most widely used drugs to treat pain and inflammation. However, clinical trials have revealed that these inhibitors predisposed patients to a significantly increased cardiovascular risk, consisting of thrombosis, hypertension, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death. Thus, microsomal prostaglandin E (PGE) synthase-1 (mPGES-1), the key terminal enzyme involved in the synthesis of inflammatory prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and the four PGE2 receptors (EP1–4) have gained much attention as alternative targets for the development of novel analgesics. The cardiovascular consequences of targeting mPGES-1 and the PGE2 receptors are substantially studied. Inhibition of mPGES-1 has displayed a relatively innocuous or preferable cardiovascular profile. The modulation of the four EP receptors in cardiovascular system is diversely reported as well. In this review, we highlight the most recent advances from our and other studies on the regulation of PGE2, particularly mPGES-1 and the four PGE2 receptors, in cardiovascular function, with a particular emphasis on blood pressure regulation, atherosclerosis, thrombosis, and myocardial infarction. This might lead to new avenues to improve cardiovascular disease management strategies and to seek optimized anti-inflammatory therapeutic options.

1. Introduction

Prostaglandin (PG) E2 is an important lipid mediator that regulates diverse and important physiological processes, such as gastric epithelial cytoprotection, renal blood flow maintenance, cardiovascular tone and blood pressure regulation, reproduction and parturition, bone formation, sleep, and neuroprotection. One of the major pathophysiological functions of PGE2 is to elicit actions such as pyrexia, pain sensation, and inflammation. Thus, the analgesic and anesthetic effects of the most widely used nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are thought to be driven by inhibition of the production of PGE2.

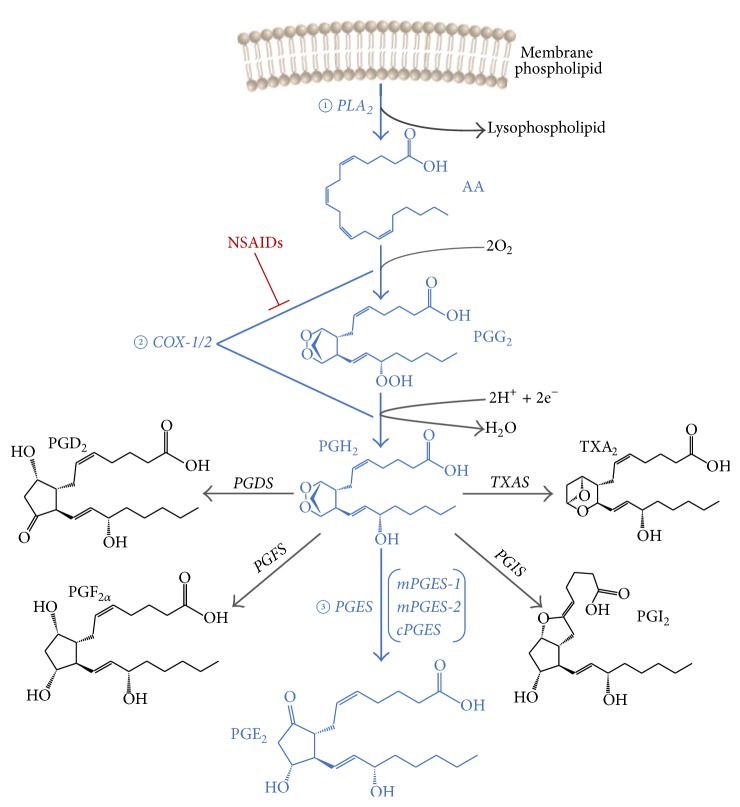

PGE2 is synthesized via three sequential enzymatic reactions (Figure 1). Firstly, arachidonic acid (AA) is released from membrane phospholipids by phospholipase A2 (cPLA2); then, AA is converted into the unstable endoperoxide intermediates PGG2 and PGH2 by cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) or COX-2. Finally, PGH2 is converted to PGE2 through three terminal PGE2 synthases, two membrane associated PGE2 synthases (mPGES-1 and mPGES-2) and a cytosolic (cPGES) PGE2 synthase [1]. COX-1 is usually constitutively expressed in most tissues and responsible for the basal production of PGE2 that is involved in homeostasis of various physiological functions, such as gastrointestinal and kidney maintenance. In contrast, the expression of COX-2 is very low in many tissues at baseline but is highly induced by proinflammatory factors, hormones, and growth factors. Its role in the production of inflammatory PGE2 and probably prostacyclin (PGI2) provided the rationale for the development of COX-2 selective NSAIDs, such as celecoxib, rofecoxib, and valdecoxib, for the management of pyrexia, relief of pain, and alleviation of inflammation with less gastrointestinal side effects [2]. However, placebo-controlled trials revealed that these drugs predisposed patients to a series of cardiovascular hazards, including hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death, affecting ~1-2% of patients exposed per year [3]. For example, the VIGOR trial showed a 0.4% increase in myocardial infarction in the patients given COX-2 selective NSAID rofecoxib, but only 0.1% increase for those given the nonselective naproxen [4]. The molecular mechanism underlying these complications has been variously studied. The leading explanation is that COX-2 inhibition depresses PGI2 formation in the vasculature which restrains platelet activation by prothrombotic stimuli. Inhibition of this mediator increases the likelihood of thrombotic events, hypertension, and heart failure particularly in patients at elevated cardiovascular risk [5].

Figure 1.

Biosynthesis pathway of prostaglandin E2.

Among the three PGESs, mPGES-2 and cPGES are constitutively expressed and had been thought to be responsible for the baseline PGE2 production. The baseline expression of mPGES-1 is relatively low in most tissues, while in response to acute and chronic inflammatory stimuli, mPGES-1 is upregulated and functionally coupled with COX-2 to mediate inflammatory PGE2 production [6]. The human mPGES-1 gene is localized to chromosome 9q34.3 and contains 3 exons and spans 14.8 kb. The protein consists of 152 amino acid residues with about 80% similarity to the enzyme in mouse, rat, or cow [7]. Owing to the undesirable effects of COX-2 selective inhibitors, interest has been focused on mPGES-1 as an alternative target for the development of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs [8]. The thought was that the analgesic efficacy would be largely, if not totally, conserved by PGE2 suppression while most of the cardiovascular risk would be minimized by conserving or even boosting the cardioprotective PGI2 production [9]. Indeed, global or myeloid specific deletion of mPGES-1 has proven efficacy in restraining atherogenesis, attenuating the proliferative response to vascular injury, and limiting aortic aneurysm formation [10–14]. However, there are also some opposite findings that global or macrophage mPGES-1 inhibition might adversely interfere with cardiac remodeling [15] and elicit hypertension [16, 17], which complicates the development of mPGES-1 inhibitors.

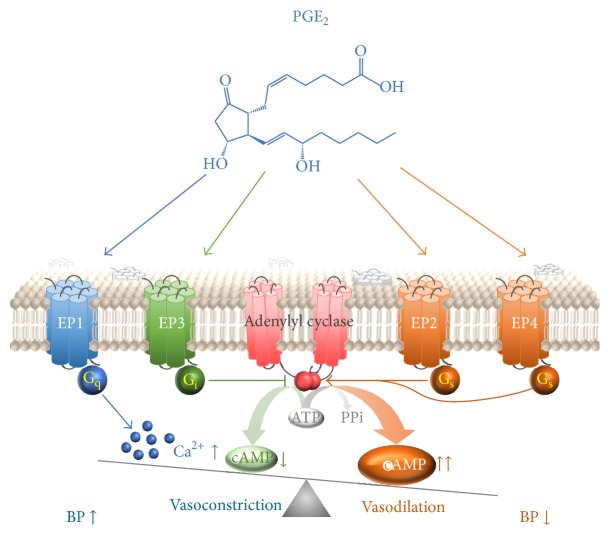

PGE2 acts on four specific G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) subtypes, termed EP1–4. Activation of these receptors by PGE2 or artificial compounds stimulates distinct signal transduction pathways and mediates various biological functions [18]. The EP1 receptor couples to Gq-proteins to increase intracellular Ca2+ concentration. The EP2 and EP4 receptors couple to Gs-proteins and evoke an increase in intracellular cAMP concentration. EP3 receptor mainly couples to Gi-proteins to decrease cAMP production, while it has at least 8 variants which may activate other different signaling pathways, for example, elevate intracellular Ca2+, or activate the small G-protein Rho. The involvement of the four PGE2 receptors in cardiovascular function has been studied with various genetic deletion approaches or small molecule agonists or antagonists, and the conclusions varied [19].

2. mPGES-1 and Blood Pressure

A change in blood pressure is a pronounced risk signal that reflects the increased cardiovascular hazard from NSAIDs. As the most promising target for next generation of analgesic and anesthetic drugs, it is of critical significance to understand the role of mPGES-1 in blood pressure regulation. Several lines of evidence point to no differences in blood pressure between mPGES-1-deficient and wild-type mice. Cheng et al. and Francois et al. reported that deletion of mPGES-1 failed to elevate blood pressure in mice fed either a normal or a high-salt diet [13, 20]. Angiotensin II induced hypertension was also uninfluenced by mPGES-1 deletion in hyperlipidemic mice [11, 21]. These results are somewhat inconsistent with the findings from Jia et al. and Zhang et al. who did note that mPGES-1 deletion augmented the hypertensive response to both salt loading and angiotensin II infusion [22, 23]. Interestingly, using Cre-LoxP mediated cell specific gene depletion, our own data illustrated that neither myeloid nor vascular cell mPGES-1 play a major role in blood pressure homeostasis, at least at baseline and hyperlipidemia conditions [14]. Howbeit, based on bone marrow transplant technology, the most recent JCI paper demonstrated that COX-2-mPGES-1 derived PGE2 in hematopoietic cells, especially macrophages, did contribute to blood pressure buffering in response to chronically increased dietary salt [16, 24]. The mechanism for these discrepancies has not been fully explored but seems to be associated with the differences in genetic background and differences in the experimental protocols [25]. Nevertheless, whether mPGES-1 inhibition will have a safety blood pressure profile compared to COX-2 selective NSAIDs will have to be evaluated further in clinical studies.

3. EP Receptors and Blood Pressure

PGE2 has been demonstrated to act as either vasodilator or vasoconstrictor depending on its binding to distinct EP receptors. The functional balance of pressor and depressor receptors activated by PGE2 plays an important role in the overall maintenance of normal blood pressure, while an imbalance may be a risk factor for development of essential hypertension [26].

Generally, activation of the EP1 and EP3 receptors is vasoconstrictive [27]. It has been clearly documented that genetic disruption of EP1 or EP3 receptors blunted the hypertensive response to acute or chronic AngII infusion; the pressor responses to EP1/EP3 agonist sulprostone were abolished in EP1 or EP3 null mice [28–31]. Similarly, pharmacologic blockade of EP1 reduces blood pressure in the spontaneously hypertensive rat [28] and restrains the development of hypertension in mice with type 2 diabetes [32]. Various EP1 or EP3 antagonists have proven efficacy in blunting the constricting effect of AngII on arterial rings ex vivo [28, 29, 32]. Furthermore, EP1 deficient mice showed reduced vasodepressor response to exogenous PGE2 administration; a more prolonged reduction in mean arterial pressure to PGE2 infusion was displayed in EP3 null mice, although no difference in the magnitude of the depressor response was observed [28, 29]. In addition, activation of EP3 receptor is verified to be responsible for the sympathetic responses to central PGE2 [33, 34], and central AngII-driven sympathetic responses are mediated by brain EP1 activation [30]. Most recently, Lu et al. demonstrated that EP3 activation can facilitate hypoxia-induced vascular remodeling and pulmonary hypertension in mice [35]. The role of EP1 activation in sympathoexcitatory responses and pulmonary hypertension is still not clear.

Contrary to EP1 and EP3, activation of the EP2 and EP4 receptors is thought to be vasodilatory. Deletion of EP2 in mice led to slightly elevated baseline systolic blood pressure, and the pressor response to PGE2 infusion was unmasked [26, 36, 37]. When challenged with a high-salt diet, the EP2 knockout mice developed profound but reversible hypertension [36]. However, it is somewhat contentious because the PGE2 caused relaxations were unchanged in rings from EP2 null mice, and only limited relaxation was observed when treated with EP2 specific agonist, butaprost [38]. Tilley et al. even reported systemic hypotension in EP2 knockout mice [39]. This distinction perhaps again reflects differences in the genetic background (C57BL/6 versus 129/SvEv). Evidence of vasodilatory function of EP4 is supported by using the aortic ring preparation, where both EP4 deletion and administration of EP4 antagonist abolished the vessel relaxation effect of PGE2 [38]. The maximal vasodepressor effect of PGE2 in vivo was also significantly buffered in EP4 deficient mice, but only in females [37]. It is of note that Zhang et al. showed that although EP4-selective agonist prostaglandin E1-OH functioned as a vasodilator, activation of EP4 receptor alone failed to battle the pressor effect of EP3 in EP2 deficient mice [26]. This suggested that the vasodepressive effects of EP2 and EP4 receptors are predominant, which leads to the net effect of blood pressure depression of PGE2. Surprisingly, a prohypertensive action of EP4 activation is reported most recently, where Wang et al. showed that inactivation of EP4 would significantly lower AngII induced hypertension in Sprague-Dawley rats [40]. Mechanically, this effect might be due to the inhibition of the protein expression of renal (pro)renin receptor and the consequent suppression of local renin-angiotensin system.

Taken together, despite an overall prohypertensive role of the EP1 and EP3 receptors and vasodepressor action of the EP2 and EP4 receptors (Figure 2), effects of PGE2 on blood pressure regulation are a complex interplay between each receptor subtype expression and other various factors in the genetic background. PGE2 in water and sodium reabsorption and renal hemodynamics plays vital roles in blood pressure control as well, while this is beyond the scope of the current review. Nevertheless, selective targeting PGE2 receptors may hold promise to develop into novel therapies for the management of hypertension and stroke.

Figure 2.

Function of EP receptors in blood pressure regulation. PGE2 increases vascular tone and thus blood pressure through EP1-mediated Ca2+ influx and EP3-mediated inhibition of cAMP synthesis, while it lowers blood pressure via EP2- and EP4-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase and cAMP synthesis.

4. mPGES-1 and Atherosclerosis and Other Inflammatory Vascular Diseases

Deletion or inhibition of COX-2 has been shown variously to promote, postpone, or leave the development of atherosclerosis unaltered in diverse rodent models [41–43]. This perhaps reflects the contrasting biological effects of different COX-2 products formed by distinct cells during disease evolution. Indeed, the functional importance of COX-2 in individual vascular cell types on atherogenesis has been extensively studied. For instance, myeloid COX-2 promotes while vascular COX-2 restrains atherogenesis in diet induced hyperlipidemic mice [44, 45]. Similarly, despite the favorable atheroprotective and antianeurysm observation of global deletion of mPGES-1 in hyperlipidemic mice [11, 12], tissue-dependent consequences of mPGES-1 blockade were observed in cellular specific knockout mice. Recently, we found that myeloid cell mPGES-1 depletion restrains the initiation and early development of atherosclerosis, which is concomitant with a reduction in iNOS-mediated oxidative stress. By contrast, disruption of mPGES-1 in vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, or both does not detectably alter atherogenesis in mice [10]. This data points to the therapeutic rationale for targeting macrophage mPGES-1 in atherosclerosis. Interestingly, unlike the global mPGES-1 KO mice, our data showed no evident alteration in urinary production of PGI2 when mPGES-1 is lacking in macrophages only [10]. This is theoretically attractive, since PGI2, which mediates pain and dominates even over PGE2 in some mouse models of analgesia, might undermine the analgesic efficacy of mPGES-1 inhibition.

A similar case was observed in a wire-induced vascular injury model. Global deletion of mPGES-1 attenuated proliferation responses to wire injury via both suppression of PGE2 and product rediversion to PGI2 [46]. However, phenotypic divergence was observed when mPGES-1 was selectively deleted in given cell types [14]. Thus, the proliferative response to vascular injury was attenuated by myeloid cell mPGES-1 depletion, whereas it was promoted by EC and VSMC mPGES-1 deletion. In this case, the results were attributable to differential consequences of EP activation in these two cell types, rather than contrasting products of PGH2 diversion.

At all events, these observations raise the possibility that the broader cardiovascular efficacies observed with global mPGES-1 deletion might be conserved by targeting myeloid mPGES-1 and that targeting macrophage mPGES-1 may be a strategy to further refine efficacy while limiting adverse effects attributable to enzyme inhibition in other tissues. Despite these promising results, given that people who received NSAIDs are usually already suffering coronary stenosis or an atherosclerotic disease, it remains a challenge that such an inhibitor caused reversal of the established atherosclerosis rather than retarding its development.

5. EP Receptors and Atherosclerosis and Other Inflammatory Vascular Diseases

Accumulating evidence demonstrated that inflammation plays a central role in the cascade of events that result in atherosclerotic plaque erosion and rupture, in which the roles of the four EP receptors have been extremely studied.

EP4 was considered as the most abundant PGE2 receptor expressed in vulnerable human atherosclerotic lesions [47]. Studies regarding the role of EP4 in atherosclerogenesis are variable. EP4 overexpression was associated with enhanced culprit matrix metalloproteinases expression and deteriorated inflammatory reaction in atherosclerotic plaques [47]. EP4 deficiency showed suppressed early atherosclerosis by promoting macrophage apoptosis [48]. Both pharmacological and genetic EP4 inhibition displayed efficiency in attenuating abdominal aortic aneurism formation in both mouse and human models [49–52]. However, in contrast to these observations, Tang et al. reported that deficiency of EP4 on bone marrow-derived cells had little effect on plaque size or morphology in early atherosclerosis but accelerated local inflammation and altered lesion composition at later stages of atherosclerosis [53]. In addition, augmented elastin fragmentation and exacerbated aneurism formation also presented in bone marrow EP4 deficient mice [54]. The discrepancy in these results could result from differences in experimental protocols or differences in genetic background among the strains used in these experiments; the pathophysiologic importance of PGE2-EP4 pathway in experimental atherosclerosis or aneurysm formation still merits further investigation.

Activation of EP2 exerts both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects in atherosclerotic plaques. Li et al. demonstrated that activation of EP2 receptor is involved in the adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells of the vessel wall, one of the earliest events during atherosclerogenesis [55]. Also upregulation of EP2 was observed in abdominal aortic aneurysm [52]. On the contrary, studies using genetically modified mice revealed that deficiency of the EP2 receptor in mice promotes VSMC proliferation and migration and augments neointimal hyperplasia after vascular injury, suggesting that activation of EP2 may have potential implications in treating pathological vascular remodeling, such as atherosclerosis and restenosis [56].

The role of EP1 and EP3 receptors in atherosclerosis received less attention. Although Cipollone et al. did not detect EP1 or EP3 expression in human atherosclerotic plaques [47], others demonstrated that expression of EP1 and EP3 is mainly located in macrophages of the plaque shoulder region [57]. A recent study showed that oxLDL suppresses EP3 expression in macrophages, thus impairing EP3-mediated anti-inflammatory and antiatherosclerotic effects [58]. Most recently, by screening various pharmacological inhibitors, Zhang et al. identified that inhibition of EP3, especially its α and β splice variants, impaired VSMC migration and restricted vascular neointimal hyperplasia, whereas overexpression of EP3α and EP3β aggravated neointima formation [59]. However, the direct effect of EP1 and EP3 on atherogenesis needs to be illustrated.

6. mPGES-1 and Thrombosis

Thrombosis is the most pronounced risk signal associated with NSAIDs [60]. Inhibition of COX-2 or deletion of IP (PGI2 receptor) significantly accelerated thrombogenesis, reflected by shortened time to vascular occlusion after photochemical injury of the carotid artery and reduced thrombogenesis after laser-induced cremaster arterioles injury [5]; however, these effects were not observed in either global or myeloid cell mPGES-1 knockout mice [10, 13]. Effects on both augmented PGI2 and suppressed PGE2 might be relevant to this beneficial phenotype: PGI2 restrains thrombogenesis, while PGE2 elicits platelet aggregation at low concentrations via EP3 [61]. Howbeit, considering the potential significance of genetic and environmental factors on blood pressure response to mPGES-1 deficiency [25], it is a prerequisite to confirm these favorable phenotypes in other genetic backgrounds and eventually in clinic studies.

7. EP Receptors and Thrombosis

PGE2 has been reported to exhibit a biphasic effect on platelet aggregation depending on its concentration. It potentiates and inhibits platelet aggregation at low and high concentrations, respectively. While EP1 expression is lacking, the other three PGE2 receptors, EP2, EP3, and EP4, are all expressed in platelets and the expression level of EP3 is much higher than EP2 and EP4. The contribution of these three receptors to PGE2 induced platelet aggregation and thrombosis is well studied. In detail, EP3 mediates the proaggregatory effect of PGE2. EP3 agonists had shown concentration-dependent potentiation of platelet aggregation in vitro [61]. In vivo, the EP3 gene depletion mice showed significantly prolonged tail bleeding time and when challenged with arachidonic acid, the lung thrombus formation and mortality both attenuated in the EP3−/− mice [62]. In addition, by mechanical rupture of the plaque with scratching in a murine model, Gross et al. showed that the atherothrombosis was drastically decreased when there was a lack of EP3 in platelets [63]. Indeed, DG-041, a direct-acting EP3 antagonist, has been considered as an effective antiplatelet and antiatherothrombosis drug without increasing bleeding risk [64, 65]. In contrast, the EP2 and EP4 signaling mediates the anti-aggregatory effects of PGE2, albeit the prostacyclin receptor (IP) plays the predominant inhibitory role at higher PGE2 concentrations. Notably, these inhibitory effects of EP2 and EP4 might only be efficient when EP3 receptor is absent; thus, unaltered inhibitory effects of PGE2 in EP2 or EP4 single knockout platelets were observed, while in EP3 and IP double deficient platelets the inhibitory effect was augmented [66]. Nevertheless, PGE2 sensitizes platelets to their agonists such as thrombin or collagen through the activation of its EP3 receptor, while PGE2 inhibits platelet activity through EP2 and EP4 receptors [66]. The net result of these opposing actions is that the stimulating effect of EP3 overcomes the inhibiting effects of EP2 and/or EP4 and leads to platelet aggregation and potentiates thrombosis [67]. Selective blockade of the EP3 activity and/or activation of EP2 or EP4 are rational strategies for developing novel antiplatelet agents and preventing thrombogenesis.

8. mPGES-1 and Myocardial Remodeling

The role of mPGES-1 inhibition in cardiac remodeling is complex. Unlike COX-2 inhibition, loss of mPGES-1 avoided the post-MI death after coronary occlusion in mice [68]. Notably, the loss of mPGES-1 did not significantly affect the circulatory PGE2 level, while it was accompanied with an induction of PGI2 after myocardial infarction (MI). Therefore, it is possible that a redirected synthesis to PGI2 compensates the loss of mPGES-1 and offers the benefit upon acute ischemia. This is also supported by the finding that pretreatment of IP antagonist in mice lacking mPGES-1 increased myocardial damage and reduced postischemia survival [69]. However, although global mPGES-1 deletion does not increase mortality, it does adversely influence myocardial remodeling after coronary artery ligation in mice. Degousee et al. showed that, twenty-eight days after MI, mPGES-1 KO mice developed more severe pathological left ventricle (LV) remodeling compared to WT, including eccentric cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, impaired LV systolic and diastolic function, LV dilation, and elevated LV end-diastolic pressure [15]. In this case, it seems that mPGES-1-derived PGE2 has beneficial effects on myocardial remodeling. It was found that the induction of the mPGES-1 protein was mainly produced from inflammatory cells of the heart after myocardial infarction [15]. Thus, by using the bone marrow transplant approach, Degousee's group further demonstrated that inactivation of mPGES-1 in bone marrow-derived leukocytes fully replicated the deleterious remodeling phenotypes and decreased the post-MI survival [70]. Surprisingly, although mPGES-1 was lacking in bone marrow leukocytes, an even higher level of PGE2 was detected in infarct and viable myocardium. This probably comes from the induction of mPGES-1 activity in cardiac fibroblasts in the chimera mice. However, this evokes an interesting paradox: either boosting or decreasing PGE2 is associated with worse LV remodeling and function. One possibility is that the deletion of mPGES-1 globally or specifically in the bone marrows renders the PGH2 substrate available for diversion to various other PG synthases. Secondly, the distinct expression or activation of the four PGE2 receptors in myocardium might result in varied biological effects of PGE2 in these two models. Nevertheless, more work is required to refine the role of PGE2 in bone marrow-derived leukocytes and in fibroblasts in mediating the remote control of myocardial remodeling. Indeed, we have new evidence that lacking mPGES-1 in myeloid cells, particularly in macrophages, promotes post-MI survival, while no detectable adverse influence on post-MI remodeling was observed (unpublished data).

9. EP Receptors and Myocardial Remodeling

Although the expression of the four EP receptors in heart varies among studies, an abundant expression of the EP4 mRNA has been reported in the heart with acute myocardial infarction [71]. Targeting EP4 has garnered much interest in treating myocardial infarction and heart failure. Indeed, administration of an EP4 agonist effectively reduced acute cardiac rejection, protected against allograft rejection, and prolonged allograft survival in mice by suppressing of inflammation during cardiac transplantation [72]. EP4 agonists also showed evidence to protect reperfused myocardium from ischemic injury, inactivation of EP4 aggravated myocardial remodeling, and impaired cardiac function in vivo [71, 73]. On the contrary, activation of EP4 mediated PGE2-induced cardiac myocyte hypertrophy in vitro [74]. Qian et al. showed that the cardiomyocytes-specific EP4 knockout mice had decreased cardiac hypertrophy and improved cardiac fibrosis while accompanied with impaired heart function outcome [75]. In this case, the myocyte EP4 induced hypertrophy seems to be cardioprotective, while the opposite effects of EP4 expression in other cell types, for example, fibroblasts and macrophages, might be another explanation. Thereby, the cell specific role of EP4 receptor in cardiac remodeling is further required. With regard to EP3, although several reports suggested a cardioprotective effect of EP3 agonists against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rodents and pigs [76–78], others demonstrated that overexpression of EP3 might activate calcineurin and promote hypertrophy after ischemia reperfusion [79]. These results suggest a dual involvement of the EP3 subtype in both cardioprotection and hypertrophy, which might be attributable to the expression diversity of EP3 isoforms in heart tissue. Most recently, Liu et al. suggested the necessity of PGE2-EP3 signaling in maintaining the normal growth and development of the heart, and they found that lacking EP3 receptor in mice would foster eccentric cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in 16–18-week-old mice even at resting condition [80]. Therefore, EP3 presents a potential therapeutic target for cardiac eccentric hypertrophy and cardiac remodeling. Unlike EP3 and EP4, the role of EP1 and EP2 receptors in cardiac remodeling is less studied. In vitro data showed that PGE2 stimulates cardiac fibroblast proliferation via EP1 [81] and mediates the effect of postischemic coronary effluent on Ca2+ transients and systolic cell shortening by EP4 and EP2 activation [82]. However, there is still no direct in vivo evidence showing that EP1 and EP2 are significantly involved in cardiac remodeling and this warrants further investigation.

10. Summary

In summary, growing evidence has illustrated the promising prospect of targeting mPGES-1, especially in macrophages, in inflammatory cardiovascular diseases, albeit further research is in need to fully pinpoint the effects and the side effects panorama of inhibiting mPGES-1. On the other hand, comprehensive data displayed a quite diverse, disease-specific contribution of individual EP receptors to cardiovascular health and diseases. More work is required to clarify the controversies and gain insight into the precise contribution of targeting each receptor. So far, specific inhibitors of mPGES-1 have advanced into clinical trials and various EP agonists and antagonists are pursued as alternative approaches to COX-2 inhibition. However, millions of patients worldwide are regular consumers of NSAIDs for pain relief and many of them are seniors (up to 40% of people 65 and older take NSAID daily)—a group already likely to have cardiovascular diseases. Thus, even the small incremental risk (~1-2%) of cardiovascular events caused by NSAIDs has been of concern. The future aim is to develop a class of drugs that not only afford pain relief but also have cardiovascular efficacy.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Yang G., Chen L., Zhang Y., et al. Expression of mouse membrane-associated prostaglandin E2 synthase-2 (mPGES-2) along the urogenital tract. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2006;1761(12):1459–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen L., Yang G., Grosser T. Prostanoids & inflammatory pain. Prostaglandins and Other Lipid Mediators. 2013;104-105:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grosser T., Yu Y., Fitzgerald G. A. Emotion recollected in tranquility: lessons learned from the cox-2 saga. Annual Review of Medicine. 2010;61:17–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-011209-153129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bombardier C., Laine L., Reicin A., et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343(21):1520–1528. doi: 10.1056/nejm200011233432103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu Y., Ricciotti E., Scalia R., et al. Vascular COX-2 modulates blood pressure and thrombosis in mice. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4(132) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003787.132ra54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norberg J. K., Sells E., Chang H. H., Alla S. R., Zhang S., Meuillet E. J. Targeting inflammation: multiple innovative ways to reduce prostaglandin E2 . Pharmaceutical Patent Analyst. 2013;2(2):265–288. doi: 10.4155/ppa.12.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forsberg L., Leeb L., Thorén S., Morgenstern R., Jakobsson P.-J. Human glutathione dependent prostaglandin E synthase: gene structure and regulation. FEBS Letters. 2000;471(1):78–82. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01367-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koeberle A., Werz O. Perspective of microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1 as drug target in inflammation-related disorders. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2015;98(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang M., FitzGerald G. A. Cardiovascular biology of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2010;20(6):189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L., Yang G., Monslow J., et al. Myeloid cell microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1 fosters atherogenesis in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(18):6828–6833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401797111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang M., Lee E., Song W., et al. Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 deletion suppresses oxidative stress and angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Circulation. 2008;117(10):1302–1309. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.731398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang M., Zukas A. M., Hui Y., Ricciotti E., Puré E., FitzGerald G. A. Deletion of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 augments prostacyclin and retards atherogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(39):14507–14512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606586103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng Y., Wang M., Yu Y., Lawson J., Funk C. D., FitzGerald G. A. Cyclooxygenases, microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1, and cardiovascular function. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116(5):1391–1399. doi: 10.1172/JCI27540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L., Yang G., Xu X., et al. Cell selective cardiovascular biology of microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1. Circulation. 2013;127(2):233–243. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.119479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Degousee N., Fazel S., Angoulvant D., et al. Microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1 deletion leads to adverse left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117(13):1701–1710. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.107.749739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang M.-Z., Yao B., Wang Y., et al. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 in hematopoietic cells results in salt-sensitive hypertension. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015;125(11):4281–4294. doi: 10.1172/jci81550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia Z., Guo X., Zhang H., Wang M.-H., Dong Z., Yang T. Microsomal prostaglandin synthase-1-derived prostaglandin E2 protects against angiotensin II-induced hypertension via inhibition of oxidative stress. Hypertension. 2008;52(5):952–959. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.108.111229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breyer R. M., Bagdassarian C. K., Myers S. A., Breyer M. D. Prostanoid receptors: subtypes and signaling. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2001;41:661–690. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ricciotti E., Fitzgerald G. A. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2011;31(5):986–1000. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francois H., Facemire C., Kumar A., Audoly L., Koller B., Coffman T. Role of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 in the kidney. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2007;18(5):1466–1475. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006040343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harding P., Yang X.-P., He Q., LaPointe M. C. Lack of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 reduces cardiac function following angiotensin II infusion. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2011;300(3):H1053–H1061. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00772.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jia Z., Zhang A., Zhang H., Dong Z., Yang T. Deletion of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 increases sensitivity to salt loading and angiotensin II infusion. Circulation Research. 2006;99(11):1243–1251. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000251306.40546.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang D.-J., Chen L.-H., Zhang Y.-H., et al. Enhanced pressor response to acute Ang II infusion in mice lacking membrane-associated prostaglandin E2 synthase-1. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2010;31(10):1284–1292. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stegbauer J., Coffman T. M. Skin tight: macrophage-specific COX-2 induction links salt handling in kidney and skin. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015;125(11):4008–4010. doi: 10.1172/jci84753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Facemire C. S., Griffiths R., Audoly L. P., Koller B. H., Coffman T. M. The impact of microsomal prostaglandin e synthase 1 on blood pressure is determined by genetic background. Hypertension. 2010;55(2):531–538. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y., Guan Y., Schneider A., Brandon S., Breyer R. M., Breyer M. D. Characterization of murine vasopressor and vasodepressor prostaglandin E2 receptors. Hypertension. 2000;35(5):1129–1134. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.5.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang T., Du Y. Distinct roles of central and peripheral prostaglandin E2 and EP subtypes in blood pressure regulation. American Journal of Hypertension. 2012;25(10):1042–1049. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2012.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guan Y., Zhang Y., Wu J., et al. Antihypertensive effects of selective prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype 1 targeting. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117(9):2496–2505. doi: 10.1172/jci29838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen L., Miao Y., Zhang Y., et al. Inactivation of the E-prostanoid 3 receptor attenuates the angiotensin II pressor response via decreasing arterial contractility. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2012;32(12):3024–3032. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.254052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao X., Peterson J. R., Wang G., et al. Angiotensin II-dependent hypertension requires cyclooxygenase 1-derived prostaglandin E2 and EP1 receptor signaling in the subfornical organ of the brain. Hypertension. 2012;59(4):869–876. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.182071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stock J. L., Shinjo K., Burkhardt J., et al. The prostaglandin E2 EP1 receptor mediates pain perception and regulates blood pressure. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;107(3):325–331. doi: 10.1172/jci6749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rutkai I., Feher A., Erdei N., et al. Activation of prostaglandin E2 EP1 receptor increases arteriolar tone and blood pressure in mice with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovascular Research. 2009;83(1):148–154. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z.-H., Yu Y., Wei S.-G., Nakamura Y., Nakamura K., Felder R. B. EP3 receptors mediate PGE2-induced hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus excitation and sympathetic activation. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2011;301(4):H1559–H1569. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00262.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ariumi H., Takano Y., Masumi A., et al. Roles of the central prostaglandin EP3 receptors in cardiovascular regulation in rats. Neuroscience Letters. 2002;324(1):61–64. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00174-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu A., Zuo C., He Y., et al. EP3 receptor deficiency attenuates pulmonary hypertension through suppression of Rho/TGF-β1 signaling. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015;125(3):1228–1242. doi: 10.1172/jci77656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kennedy C. R. J., Zhang Y., Brandon S., et al. Salt-sensitive hypertension and reduced fertility in mice lacking the prostaglandin EP2 receptor. Nature Medicine. 1999;5(2):217–220. doi: 10.1038/5583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Audoly L. P., Tilley S. L., Goulet J., et al. Identification of specific EP receptors responsible for the hemodynamic effects of PGE2. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 1999;277(3):H924–H930. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.3.H924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hristovska A.-M., Rasmussen L. E., Hansen P. B. L., et al. Prostaglandin E2 induces vascular relaxation by E-prostanoid 4 receptor-mediated activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Hypertension. 2007;50(3):525–530. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.088948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tilley S. L., Audoly L. P., Hicks E. H., et al. Reproductive failure and reduced blood pressure in mice lacking the EP2 prostaglandin E2 receptor. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;103(11):1539–1545. doi: 10.1172/jci6579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang F., Lu X., Peng K., et al. Prostaglandin E-prostanoid4 receptor mediates angiotensin II-induced (Pro)renin receptor expression in the rat renal Medulla. Hypertension. 2014;64(2):369–377. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.114.03654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Egan K. M., Wang M., Lucitt M. B., et al. Cyclooxygenases, thromboxane, and atherosclerosis: plaque destabilization by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition combined with thromboxane receptor antagonism. Circulation. 2005;111(3):334–342. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000153386.95356.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burleigh M. E., Babaev V. R., Oates J. A., et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 promotes early atherosclerotic lesion formation in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Circulation. 2002;105(15):1816–1823. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000014927.74465.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burleigh M. E., Babaev V. R., Yancey P. G., et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 promotes early atherosclerotic lesion formation in ApoE-deficient and C57BL/6 mice. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2005;39(3):443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hui Y., Ricciotti E., Crichton I., et al. Targeted deletions of cyclooxygenase-2 and atherogenesis in mice. Circulation. 2010;121(24):2654–2660. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.910687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang S. Y., Monslow J., Todd L., Lawson J., Puré E., Fitzgerald G. A. Cyclooxygenase-2 in endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells restrains atherogenesis in hyperlipidemic mice. Circulation. 2014;129(17):1761–1769. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang M., Ihida-Stansbury K., Kothapalli D., et al. Microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1 modulates the response to vascular injury. Circulation. 2011;123(6):631–639. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.973685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cipollone F., Fazia M. L., Iezzi A., et al. Association between prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP4 overexpression and unstable phenotype in atherosclerotic plaques in human. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2005;25(9):1925–1931. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000177814.41505.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Babaev V. R., Chew J. D., Ding L., et al. Macrophage ep4 deficiency increases apoptosis and suppresses early atherosclerosis. Cell Metabolism. 2008;8(6):492–501. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yokoyama U., Ishiwata R., Jin M.-H., et al. Inhibition of EP4 signaling attenuates aortic aneurysm formation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036724.e36724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cao R. Y., St Amand T., Li X., et al. Prostaglandin receptor EP4 in abdominal aortic aneurysms. The American Journal of Pathology. 2012;181(1):313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dilme J. F., Sola-Villa D., Bellmunt S., Romero J. M., Escudero Camacho M., Jr., Vila L. Active smoking increases microsomal pge2-synthase-1/pge-receptor-4 axis in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Mediators of Inflammation. 2014;2014:11. doi: 10.1155/2014/316150.316150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Camacho M., Dilmé J., Solà-Villà D., et al. Microvascular cox-2/mpges-1/ep-4 axis in human abdominal aortic aneurysm. Journal of Lipid Research. 2013;54(12):3506–3515. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M042481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang E. H. C., Shimizu K., Christen T., et al. Lack of EP4 receptors on bone marrow-derived cells enhances inflammation in atherosclerotic lesions. Cardiovascular Research. 2011;89(1):234–243. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang E. H. C., Shvartz E., Shimizu K., et al. Deletion of EP4 on bone marrow-derived cells enhances inflammation and angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2011;31(2):261–269. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.216580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li R., Mouillesseaux K. P., Montoya D., et al. Identification of prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype 2 as a receptor activated by OxPAPC. Circulation Research. 2006;98(5):642–650. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000207394.39249.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu S., Xue R., Zhao P., et al. Targeted disruption of the prostaglandin E2 e-prostanoid 2 receptor exacerbates vascular neointimal formation in mice. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2011;31(8):1739–1747. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.111.226142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gómez-Hernández A., Martín-Ventura J. L., Sánchez-Galán E., et al. Overexpression of COX-2, prostaglandin E synthase-1 and prostaglandin E receptors in blood mononuclear cells and plaque of patients with carotid atherosclerosis: regulation by nuclear factor-κB. Atherosclerosis. 2006;187(1):139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sui X., Liu Y., Li Q., et al. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein suppresses expression of prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP3 in human THP-1 macrophages. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110828.0110828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang J., Zou F., Tang J., et al. Cyclooxygenase-2-derived prostaglandin E2 promotes injury-induced vascular neointimal hyperplasia through the E-prostanoid 3 receptor. Circulation Research. 2013;113(2):104–114. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.113.301033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Patrignani P., Tacconelli S., Capone M. L. Risk management profile of etoricoxib: an example of personalized medicine. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 2008;4(5):983–997. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fabre J.-E., Nguyen M., Athirakul K., et al. Activation of the murine EP3 receptor for PGE2 inhibits cAMP production and promotes platelet aggregation. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;107(5):603–610. doi: 10.1172/jci10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ma H., Hara A., Xiao C.-Y., et al. Increased bleeding tendency and decreased susceptibility to thromboembolism in mice lacking the prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP3 . Circulation. 2001;104(10):1176–1180. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.094003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gross S., Tilly P., Hentsch D., Vonesch J.-L., Fabre J.-E. Vascular wall-produced prostaglandin E2 exacerbates arterial thrombosis and atherothrombosis through platelet EP3 receptors. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204(2):311–320. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heptinstall S., Espinosa D. I., Manolopoulos P., et al. DG-041 inhibits the EP3 prostanoid receptor—a new target for inhibition of platelet function in atherothrombotic disease. Platelets. 2008;19(8):605–613. doi: 10.1080/09537100802351073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tilly P., Charles A.-L., Ludwig S., et al. Blocking the EP3 receptor for PGE2 with DG-041 decreases thrombosis without impairing haemostatic competence. Cardiovascular Research. 2014;101(3):482–491. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuriyama S., Kashiwagi H., Yuhki K.-I., et al. Selective activation of the prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP2or EP4 leads to inhibition of platelet aggregation. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2010;104(4):796–803. doi: 10.1160/TH10-01-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mawhin M.-A., Tilly P., Fabre J.-E. The receptor EP3 to PGE2: a rational target to prevent atherothrombosis without inducing bleeding. Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediators. 2015;121:4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu D., Mennerich D., Arndt K., et al. Comparison of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 deletion and COX-2 inhibition in acute cardiac ischemia in mice. Prostaglandins and Other Lipid Mediators. 2009;90(1-2):21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu D., Mennerich D., Arndt K., et al. The effects of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 deletion in acute cardiac ischemia in mice. Prostaglandins Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids. 2009;81(1):31–33. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Degousee N., Simpson J., Fazel S., et al. Lack of microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1 in bone marrow-derived myeloid cells impairs left ventricular function and increases mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;125(23):2904–2913. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.112.099754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xiao C.-Y., Yuhki K.-I., Hara A., et al. Prostaglandin E2 protects the heart from ischemia-reperfusion injury via its receptor subtype EP4 . Circulation. 2004;109(20):2462–2468. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000128046.54681.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ogawa M., Suzuki J.-I., Kosuge H., Takayama K., Nagai R., Isobe M. The mechanism of anti-inflammatory effects of prostaglandin E2 receptor 4 activation in murine cardiac transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;87(11):1645–1653. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a5c84c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hishikari K., Suzuki J.-I., Ogawa M., et al. Pharmacological activation of the prostaglandin E2 receptor EP4 improves cardiac function after myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovascular Research. 2009;81(1):123–132. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mendez M., LaPointe M. C. PGE2-induced hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes involves EP4 receptor-dependent activation of p42/44 MAPK and EGFR transactivation. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2005;288(5):H2111–H2117. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00838.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Qian J.-Y., Harding P., Liu Y., Shesely E., Yang X.-P., LaPointe M. C. Reduced cardiac remodeling and function in cardiac-specific EP4 receptor knockout mice with myocardial infarction. Hypertension. 2008;51(2):560–566. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.107.102590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zacharowski K., Olbrich A., Piper J., Hafner G., Kondo K., Thiemermann C. Selective activation of the prostanoid EP3 receptor reduces myocardial infarct size in rodents. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 1999;19(9):2141–2147. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.9.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hohlfeld T., Meyer-Kirchrath J., Vogel Y.-C., Schrör K. Reduction of infarct size by selective stimulation of prostaglandin EP3 receptors in the reperfused ischemic pig heart. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2000;32(2):285–296. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martin M., Meyer-Kirchrath J., Kaber G., et al. Cardiospecific overexpression of the prostaglandin EP3 receptor attenuates ischemia-induced myocardial injury. Circulation. 2005;112(3):400–406. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.104.508333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meyer-Kirchrath J., Martin M., Schooss C., et al. Overexpression of prostaglandin EP3 receptors activates calcineurin and promotes hypertrophy in the murine heart. Cardiovascular Research. 2009;81(2):310–318. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu S., Ji Y., Yao J., et al. Knockout of the prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype 3 promotes eccentric cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in mice. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1074248416642520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Harding P., LaPointe M. C. Prostaglandin E2 increases cardiac fibroblast proliferation and increases cyclin D expression via EP1 receptor. Prostaglandins Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids. 2011;84(5-6):147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Birkenmeier K., Janke I., Schunck W.-H., et al. Prostaglandin receptors mediate effects of substances released from ischaemic rat hearts on non-ischaemic cardiomyocytes. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;38(12):902–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]