Abstract

Background and aim: Percutaneous endoscopic colostomy provides an alternative management option for patients with recurrent sigmoid volvulus who are considered too high risk to undergo surgery. We reviewed the literature to assess whether the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines published in 2006 supporting the use of percutaneous endoscopic colostomy are still valid.

Methods: A systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase. The exploded search terms “Percutaneous Endoscopic Colostomy” and “Sigmoid Volvulus” were used. Librarian support was used to ensure the maximum number of relevant articles were returned. Identified abstracts were then analyzed and included if they met the inclusion criteria.

Results: Five observational studies and 5 case reports were identified that met the inclusion criteria. They provided data on 56 patients with recurrent sigmoid volvulus treated with percutaneous endoscopic colostomy placement. Sixteen of the 56 patients were treated with a single percutaneous endoscopic colostomy (PEC) tube while 38 patients were treated with 2 PEC tubes. For 2 patients the details of the procedure were unknown. Five patients developed major complications following the procedure: 1 patient developed peritonitis after 4 days, due to fecal contamination secondary to tube migration and 2 patients with cognitive impairment pulled their PEC tubes out. Two other patients died following PEC insertion. Nine patients developed minor complications following the procedure. The most commonly reported minor complication was infection at the PEC site. Four of 56 patients developed a recurrent sigmoid volvulus with a PEC tube in situ.

Conclusion: Although in these case series there is a 21 % risk of morbidity and 5 % risk of mortality from the use of a PEC, this is favorable compared to the mortality risk of 6.6 % to 44 % reported with operative intervention. This review of contemporary literature therefore supports the use of PEC in frail and elderly patients.

Introduction

Volvulus is the underlying cause of 5 % to 8 % of all bowel obstructions with sigmoid volvulus accounting for 40 – 70 % of colonic volvulus 1. Sigmoid volvulus occurs when the sigmoid colon twists on its mesenteric axis 2. The patient demographic varies across the world, however, in Western populations, patients tend to be elderly with significant comorbidities 3. Predisposing factors for sigmoid volvulus are thought to be a long redundant loop of sigmoid colon with an elongated mesentery 4, chronic constipation, and neurological diseases 5.

Patients present with absolute constipation and abdominal distention. The diagnosis is usually confirmed on abdominal x-ray or, if there is diagnostic doubt, with computed tomography 6. Initial treatment is with endoscopic decompression but the risk of recurrence is high (40 %-90 %) 7 8 as the procedure is not curative. Large bowel resection is the “gold standard” management for recurrent sigmoid volvulus but emergency resection has been reported to carry a mortality of up to 50 % 9. The challenge in these patients is that recurrent sigmoid volvulus is associated with a mortality of 7 % 5 and therefore there is a need to try and treat them definitively while avoiding the risk of surgery. Percutaneous endoscopic colostomy provides an alternative management option for frail and elderly patients who are felt to be too high risk for surgery.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines published in 2006 highlight the different options available for the treatment of sigmoid volvulus. They also explain that open resection may be contraindicated in frail or elderly patients. The guidelines subsequently state that percutaneous endoscopic colostomy offers an alternative treatment option for those who are unfit for surgery or who have tried alternatives without success 10.

This paper reviews the current literature evaluating percutaneous endoscopic colostomy as a definitive treatment for recurrent sigmoid volvulus in patients where surgery is felt not to be an option and assesses whether the 2006 NICE guidelines 10 are still valid.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase. Only English language papers were included. The exploded search terms “Percutaneous Endoscopic Colostomy” and “Sigmoid Volvulus” were used. Librarian support was used to ensure that the maximum number of relevant articles were returned. Published abstracts from meetings and letters were excluded on the basis that they provided insufficient evidence for comparison.

The abstracts identified in the literature search were then analyzed and included if they used percutaneous endoscopic colostomy to treat sigmoid volvulus either as a single intervention or compared to surgery. Studies that used percutaneous endoscopic colostomy to treat a number of conditions including sigmoid volvulus were included if the results from sigmoid volvulus patients could be separated from the other conditions. Backward chaining was used to identify any papers that had been missed in the original database search. The papers were then graded according to the strength of evidence they provided.

Results

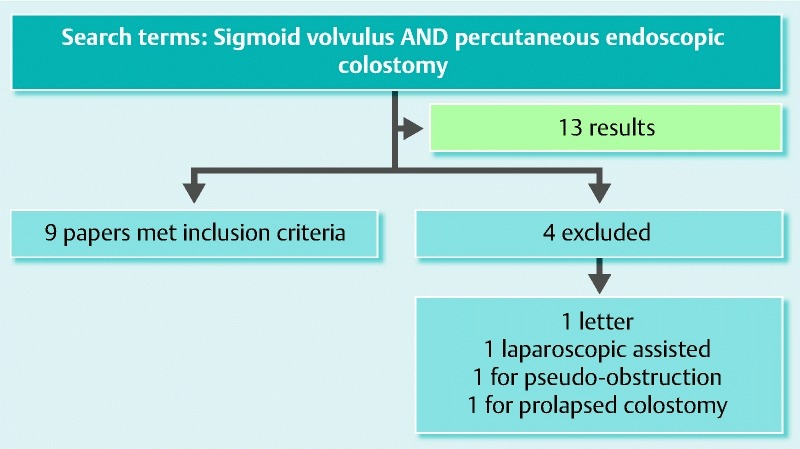

Five observational studies and 5 case reports were identified which met the inclusion criteria. They provided data on 56 patients with recurrent sigmoid volvulus treated with percutaneous endoscopic colostomy placement. All the patients were considered too high risk for resectional surgery or had repeatedly refused it. The risk of resectional surgery was assessed using the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) fitness score or World Health Organization performance status. Significant comorbidities and frailty were also considered when assessing fitness for surgery. The largest and only prospective study involved 19 patients 11. A flowchart of the search strategy used for PubMed is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of PubMed search strategy. One further relevant paper identified with librarian support.

Procedure

Where specific information on the procedure was available, all techniques for PEC tube placement were comparable. All patients were given prophylactic intravenous (IV) antibiotics at the time of the procedure and closely observed afterward for complications. The patients were all given conscious sedation and the site of the PEC tube was identified using transillumination 7 11 12 or fluoroscopy 2. Techniques using 1 or 2 PEC tubes for fixation are both described. Full results by paper are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Details of studies using percutaneous endoscopic colostomy to treat recurrent sigmoid volvulus.

| Paper | Type of paper | No. of patients | Patient characteristics | Method of PEC | Type of device used | PEC tubes removed | Recurrence of volvulus? | Length of follow up | Complications |

| Choi and Carter (1998) | Case report | 1 | 93-year-old lady, full-time nursing care, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, TIAs, heart failure, not suitable for GA | 2 PEC tubes sited | Standard PEG equipment, 2 points selected 15 cm either side of the apex. | Both removed at 1 month | No | 9 months | Nil |

| Daniels et al (2000) | Retrospective observational study | 14 | Mean age: 78 yr (Age range 53 – 99). Conventional surgery considered unsafe or inappropriate. | 2 PEC tubes sited | 14Fr gastrostomy tube (Freka, Frenius, Warrington,UK) | 8 removed at 6 weeks | 3 /8 when PEC tubes removed after 6 weeks | 7 – 21 months (mean 12.6 months) | 1 patient pulled PEC tube out after 24 hr and therefore underwent sigmoid resection. |

| Baraza et al (2007) | Prospective observational study | 19 | ASA III or more, poor candidates for surgery. Median Age 79 yr (Age range 65 – 99) | 2 PEC tubes sited (only 1 PEC tube sited in 5 patients due to frailty and technical difficulties) | Corflo® 20 Fr PEG tube | 6 /19 patients requested tube removal between 5 and 26 months | 1 recurrence after 2nd PEC tube was removed secondary to infection. | Median follow up 35 months (21 – 89 months) | 1 /19 developed peritonitis secondary to tube migration, 7/19 minor complications (2 abdominal wall bleeds, 4 site infections, 1 buried bumper). 1/19 failure to insert PEC tube. |

| Cowlam et al (2007) | Retrospective observational study | 8 | Mean Age: 80.4 yr, Median WHO performance status: 3, Median number of comorbidities: 2 | Single PEC tube | Corflo® 14Fr or 20Fr PEG tube or Corflo® 12 Fr PEC tube | 3 removed/dislodged | nil | Mean 8.8 months with PEC tube in situ (SEM ± 2.30 months) | 1 episode of buried bumper syndrome, 1 episode of granulation, 1 episode of fecal leakage and 7 infective episodes per 100 patient months with PEC tube in situ. |

| Mullen et al (2009) | Case report | 1 | 87-year-old woman, bed bound nursing home resident, previous subarachnoid and intracerebral hemorrhage with significant motor deficit | Single PEC tube | Corflo® 16Fr PEG tube | nil | nil | 3 months | Nil |

| Al-Alawi, 2010 | Case report | 1 | 93-year-old man with AF on warfarin, IHD and asthma | 2 PEC tubes sited | 20Fr PEG tube | 1 of 2 removed after 20 months as had eroded through the skin. | 1 recurrence 6 months after proximal PEC tube removed | 2 years | Nil |

| Molina-Infante et al, 2012 | Case report | 1 | 83-year-old woman, severe silated cardiomyopathy and nursing home resident refused surgery. | Single PEC tube | 22Fr PEG tube | Nil | 1 after 7 weeks | 7 weeks | After recurrent volvulus successfully detorsioned, perforated and required laparotomy, died 24 hours later |

| Toebosch et al, 2012 | Case report | 1 | 73-year-old woman, severe Parkinson’s disease, previous breast cancer and resection of local recurrence. | Single PEC tube | PEC tube placed (no details of device available) | Nil | 1 after 2 years | 2 years | Nil |

| Khan et al (2013) | Retrospective observational study | 8 | Median age 88 yr (range 85 – 95) | 2 PEC tubes sited | 15Fr PEG tube (Freka, Frenius, Warrington,UK) | 2 | 2 after PEC tubes removed. | Median 12 months (6 – 24 months) | 1 leakage at PEC site, 1 postoperative pain |

| Ifverson and Kjaer (2014) | Retrospective observational Study | 2 | 2 patients deemed unfit for surgery | No details | No details | No | No details | No details | In 1 patient derotation was not achieved prior to fixation. 1 patient died after 36 days and the other after 9 months. |

One vs 2 PEC tubes for fixation

Sixteen of the 56 patients were treated with a single percutaneous endoscopic colostomy tube while 38 patients were treated with 2 percutaneous endoscopic colostomy tubes. In 5 patients insertion of 2 PEC tubes was planned but due to “frailty and technical difficulties,” only 1 tube was sited 11. For 2 patients there was no information about the number of PEC tubes or the method of insertion 5.

Complications

Despite administration of prophylactic antibiotics, each observational study described a number of complications secondary to PEC tube placement, the most common of which was wound infection; a number of patients developed major complications including peritonitis. Cowlam et al 12 published their complication data as complications per 100 patient-months with PEC tube in situ, which meant that it was not possible to directly compare their complication rate with that from other studies in which absolute figures were published.

Major Complications

Five of 56 patients developed major complications following PEC tube insertion. Two patients with cognitive impairment (1 with learning difficulties, 1 with dementia) pulled their PEC tubes out, 1 24 hours after insertion 7 and the other after 1 year. One patient developed peritonitis after 4 days, due to fecal contamination secondary to tube migration. This was managed conservatively due to the patient’s ASA and the patient died 7 days post-procedure 11. Two further patients died following PEC tube insertion, 1 after 36 days and the other after 9 months 5.

Minor Complications

Nine patients developed minor complications following the procedure. The most commonly reported minor complication was infection at the PEC site, which occurred in 4 patients and was resolved with antibiotics in all but 1 patient 11. Two instances of abdominal wall bleeds were described. One patient developed buried bumper syndrome (managed conservatively due to frailty) 11. Khan et al 2 described 2 other minor complications: leakage at the PEC site in 1 patient and significant postoperative pain in another patient. Cowlam et al 12 described 1 episode of buried bumper, 1 episode of granulation, and 1 of fecal leakage per 100 patient-months with PEC tube in situ. They also reported that infection was the most common complication, with 7 infective episodes per 100 patient-months with PEC tube in situ.

Recurrence of Volvulus and Removal of PEC tubes

Four of 56 patients developed a recurrent sigmoid volvulus with a PEC tube in situ 11 13 14 15. The first occurred 7 weeks after insertion of a single PEC tube below the level of fixation. Although the volvulus was successfully detorsioned at colonoscopy, the patient developed severe abdominal pain and a massive pneumoperitoneum was shown on computed tomography. At laparotomy a 1-cm hole was seen on the sigmoid colon with stool spillage. The patient underwent a Hartmann’s procedure but died 24 hours later 14. Two other patients developed recurrent sigmoid volvulus when 1 of their 2 PEC tubes was removed. Both patients were successfully treated by reinserting a second PEC tube 11 15. The final patient developed a recurrent sigmoid volvulus 2 years after a single PEC tube was successfully used to treat his recurrent sigmoid volvulus. No complications were described in the intervening period 13.

Choi and Carter 16 removed both PEC tubes after 1 month with no complications. However, when Daniels et al 7 removed the colostomy tubes at 6 weeks in the first 8 patients that they treated, 3 patients developed recurrent sigmoid volvulus, so subsequent tubes were left in situ indefinitely. Three patients in the Cowlam et al 12 study had their PEC tubes removed or dislodged, 1 patient underwent definitive surgery, 1 patient died from fecal peritonitis, and 1 patient remained symptom free.

In the Baraza et al 11 study, 6 of 19 patients requested that tubes be removed between 5 and 26 months with no subsequent relapse. However, 2 patients in the Khan study 2 developed recurrent sigmoid volvuluses when their PEC tubes were removed and had to undergo a further procedure to have them reinserted.

Follow up

In all the studies there were a significant number of deaths from unrelated causes during the follow-up period. The length of follow up described was variable, the shortest being 3 months 3 and the longest 89 months 11.

Discussion

The data available on percutaneous endoscopic colostomy to treat sigmoid volvulus are limited. There is no level 1 or level 2 evidence available and the current published studies are small and predominantly retrospective in nature, leading to inferential uncertainty of the results.

This review supports the view that 2-point fixation and permanent PEC improves outcome 2 as there were no episodes of recurrent sigmoid volvulus with 2 PEC tubes in situ. Four of 16 patients (25 %) developed recurrent sigmoid volvulus with a single PEC tube in situ. Interestingly in 2 patients with PECs in situ, that occurred when 1 of the PEC tubes was removed and no further recurrences occurred once the second PEC tube had been replaced 11 15. Daniels et al 7 demonstrated that there was no residual fixation between the colon and abdominal wall when the PEC tubes were removed after 6 weeks. Baraza et al 11 removed 6 PEC tubes on patient request after a minimum of 5 months. This did not result in any subsequent relapse, perhaps suggesting that adhesions slowly form between the sigmoid colon and the anterior abdominal wall to prevent further episodes of sigmoid volvulus even after PEC tube removal. The majority of patients found having a long-term PEC tube in situ acceptable 3 7 and, therefore, from the current evidence we would recommend keeping 2 PEC tubes in situ indefinitely.

One challenge with percutaneous endoscopic colostomy is the technical difficulty associated with insertion. Five patients in the Baraza study 11 only had 1 PEC tube sited “because of frailty and technical difficulties.” Khan et al 2 described 3 patients who needed multiple PEC procedures due to “failure, technical reasons or poor bowel prep.” Baraza et al 10 also highlighted the potential for misidentifying the location of the colonoscope using transillumination alone as these patients often have long redundant loops of sigmoid. They therefore recommended using a scope guide to check positioning prior to PEC siting.

Two patients complained about the position of their PEC tubes 11. The scope guide may help to rectify this issue although it may be necessary to involve specialist nurses in a similar manor to pre-operative stoma siting to ensure that the PEC tubes are in a convenient position for both patients and carers if they are to remain in situ indefinitely.

One patient with learning difficulties and 1 patient with dementia inadvertently pulled their PEC tubes out, 1 underwent sigmoid resection and the other developed peritonitis and it was felt was unsuitable for surgical intervention 7 12. These 2 cases suggest that PEC tubes are not safe in patients with cognitive impairment due to the need for the PEC tube to remain in situ for a prolonged period of time.

Cowlam et al 12 argued that the complication rate was too high to support the widespread use of PEC. The complication rate, however, has to be considered in the context of treating patients who were ASA III or IV with significant comorbidities. In these case series there is a 21 % risk of morbidity and 5 % risk of mortality from the use of a PEC, which is favorable compared to the mortality risk of 6.6 % to 44 % reported with operative intervention 17.

Infection was the most commonly reported complication. Baraza et al 11 reported infections in 4 out of 19 patients, which is similar to the infection rate described in the NICE guidelines 10. Cowlam et al 12 reported 1 or more episodes of infection in 77 % patients. That is much higher than reported in previous studies, although the reason for it was unclear. Routinely giving IV antibiotics for 24 hours post procedure could help lower the infection rate, especially as many of these patients are vulnerable to infections.

Prolonged follow up of these patients is challenging due to the high death rate from unrelated causes. Sixteen patients died from unrelated causes during follow up. This high death rate demonstrates the frailty of these patients. It is therefore important to focus outcomes on recurrence of volvulus and complications as these have a significant impact on quality of life.

Conclusions

Three observational studies and 4 case studies have been published since issuance of the 2006 NICE guidelines on percutaneous endoscopic colostomy to treat recurrent sigmoid volvulus. Overall these studies add to the evidence base to support the use of PEC in frail and elderly patients. The current evidence suggests that placement of 2 PEC tubes reduces the risk of recurrent sigmoid volvulus. PEC tubes should be left in situ indefinitely due to the risk of recurrent symptoms once they are removed. Larger studies with a longer follow-up period are needed to identify the longer-term risks and benefits of this procedure.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None

References

- 1.Kulkarni K, Lakhani N, Cope A. et al. A growing abdominal problem. BMJ. 2013;347:f4547. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan M AS, Ullah S, Beckly D. et al. Percutaneous endoscopic colostomy (PEC): An effective alternative in high risk patients with recurrent sigmoid volvulus. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:806–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mullen R, Church N, Yalamarthi S. Volvulus of the sigmoid colon treated by percutaneous endoscopic colostomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:e64–e66. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31819e9be0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safioleas M, Chatziconstantinou C, Felekouras E. et al. Clinical considerations and therapeutic strategy for sigmoid volvulus in the elderly: A study of 33 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:921–924. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i6.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ifversen A KW, Kjaer D W. More patients should undergo surgery after sigmoid volvulus. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:18384–18389. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larkin J O, Thekiso T B, Waldron R. et al. Recurrent sigmoid volvulus – early resection may obviate later emergency surgery and reduce morbidity and mortality. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91:205–209. doi: 10.1308/003588409X391776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels I R, Lamarelli M J, Chave H. et al. Recurrent sigmoid volvulus treated by percutaneous endoscopic colostomy. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1419. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grossmann E M, Longo W E, Stratton M D. et al. Sigmoid volvulus in Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:414–418. doi: 10.1007/BF02258311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madiba T E, Thomson S R. The management of sigmoid volvulus. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2000;45:74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2006. Percutaneous endoscopic colostomy.

- 11.Baraza W, Brown S, McAlindon M. et al. Prospective analysis of percutaneous endoscopic colostomy at a tertiary referral centre. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1415–1420. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cowlam S, Watson C, Elltringham M. et al. Percutaneous endoscopic colostomy of the left side of the colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:1007–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toebosch S, Tudyka V, Masclee A. et al. Treatment of recurrent sigmoid volvulus in Parkinson’s disease by percutaneous endoscopic colostomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5812–5815. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i40.5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molina-Infante J, Fernandez-Bermejo M, Mateos-Rodriguez J M. Recurrent sigmoid volvulus and fatal peritonitis after percutaneous endoscopic sigmoidoscopy. Endoscopy. 2012;44 02 doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Alawi I. Percutaneous endoscopic colostomy: a new technique for the treatment of recurrent sigmoid volvulus. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:120–121. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.61241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi D, Carter R. Endoscopic sigmoidopexy: a safer way to treat sigmoid volvulus? J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998;43:64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oren D, Atamanalp S S, Aydinli B. et al. An algorithm for the management of sigmoid colon volvulus and the safety of primary resection: experience with 827 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:489–497. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0821-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]