Abstract

Pseudomonas lutea OK2T (=LMG 21974T, CECT 5822T) is the type strain of the species and was isolated from the rhizosphere of grass growing in Spain in 2003 based on its phosphate-solubilizing capacity. In order to identify the functional significance of phosphate solubilization in Pseudomonas Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria, we describe here the phenotypic characteristics of strain OK2T along with its high-quality draft genome sequence, its annotation, and analysis. The genome is comprised of 5,647,497 bp with 60.15 % G + C content. The sequence includes 4,846 protein-coding genes and 95 RNA genes.

Keywords: Pseudomonad, Phosphate-solubilizing, Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), Biofertilizer

Introduction

Phosphorus, one of the major essential macronutrients for plant growth and development, is usually found in insufficient quantities in soil because of its low solubility and fixation [1, 2]. Since phosphorus deficiency in agricultural soil is limits plant growth, the release bound phosphorus from soils by microbes is an important aspect that can be used to improve soil fertility for increasing crop yields [2].

Phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms, a group of soil microorganisms capable of converting insoluble phosphate to soluble forms, have received attention as efficient bio-fertilizers for enhancing the phosphate availability for plants [3]. As one of the representative phosphate-solubilizing bacteria [4], rhizosphere-colonizing pseudomonads are of interest owing to the benefits they offer to plants. Besides increasing the phosphate accessibility, they promote plant development by facilitating direct and indirect plant growth promotion through the production of phytohormones and enzymes or through the suppression of soil-borne diseases by inducing systemic resistance in the plants [5–7].

Pseudomonas lutea OK2T (=LMG 21974T, CECT 5822T) with insoluble phosphate-solubilizing activity was isolated from the rhizosphere of grass growing in northern Spain [8]. Characteristics of the whole genome sequence and a brief summary of the phenotype for this type strain are presented in this study.

Organism information

Classification and features

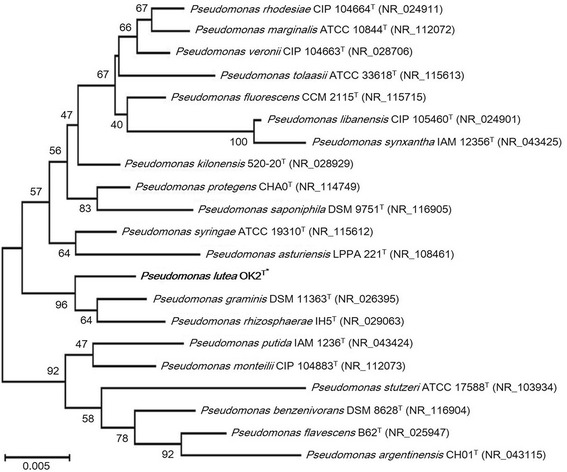

A 16S rRNA gene sequence of P. lutea OK2T was compared to those of other type strains of the genus Pseudomonas using BLAST on NCBI [9]. The 16S rRNA gene sequence showed highest similarity (99 % identity) to that of P. graminisDSM 11363T [10], followed by similarity to the 16S rRNA gene sequence of P. rhizosphaeraeIH5T (98 % identity) [11], P. protegensCHA0T (98 % identity) [12, 13], P. rhodesiaeCIP 104664T (97 % identity) [14], and P. argentinensisCH01T (97 % identity) [15]. Species showing full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences in BLAST analysis were considered for further phylogenetic analyses. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method [16], and the bootstrap value was set as 1,000 times random replicate sampling. The consensus phylogenetic neighborhood of P. lutea OK2T within the genus Pseudomonas is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A phylogenetic tree constructed using the neighbor-joining method presenting the position of Pseudomonas lutea OK2T (shown in bold print with asterisk) relative to the other species within the genus Pseudomonas. Only the type strains from the genus Pseudomonas presenting full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences were selected from the NCBI database [43]. The nucleotide sequences of these strains were aligned using CLUSTALW [44], and a phylogenetic tree was constructed with the MEGA version 6 package [45] using the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates [16]. The bootstrap values for each species are indicated at the nodes. Scale bar indicates 0.005 nucleotide change per nucleotide position. The strains selected for the analysis of the 16S rRNA gene and their corresponding GenBank accession numbers are as follows: Pseudomonas rhodesiae CIP 104664T (NR_024911) [14, 46]; Pseudomonas marginalis ATCC 10844T (NR_112072) [47, 48]; Pseudomonas veronii CIP 104663T (NR_028706) [49]; Pseudomonas tolaasii ATCC 33618T (NR_115613) [47, 50]; Pseudomonas fluorescens CCM 2115T (NR_115715) [47, 51]; Pseudomonas libanensis CIP 105460T (NR_024901) [52]; Pseudomonas synxantha IAM 12356T (NR_043425) [47, 53]; Pseudomonas kilonensis 520-20T (NR_028929) [54]; Pseudomonas protegens CHA0T (NR_114749) [13, 55]; Pseudomonas saponiphila DSM 9751T (NR_116905) [56, 57]; Pseudomonas syringae ATCC 19310T (NR_115612) [47, 58]; Pseudomonas asturiensis LPPA 221T (NR_108461) [59]; Pseudomonas graminis DSM 11363T (NR_026395) [10]; Pseudomonas rhizosphaerae IH5T (NR_029063) [11]; Pseudomonas putida IAM 1236T (NR_043424) [47, 60]; Pseudomonas monteilii CIP 104883T (NR_112073) [61]; Pseudomonas stutzeri ATCC 17588T (NR_103934) [47, 62]; Pseudomonas benzenivorans DSM 8628T (NR_116904) [56, 57]; Pseudomonas flavescens B62T (NR_025947) [63]; and Pseudomonas argentinensis CH01T (NR_043115) [15]

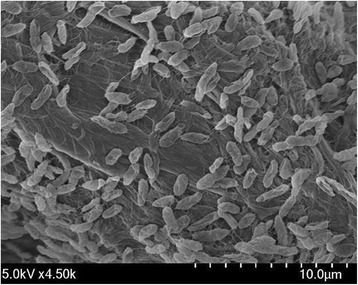

P. lutea OK2T is a motile, strictly aerobic, non-spore forming, gram-negative bacterium that belongs to the family Pseudomonadaceae of the class Gammaproteobacteria [8]. The cells are rod-shaped with a diameter of approximately 0.75 μm and a length of 1.2–1.6 μm (Fig. 2). The strain produces yellow, translucent, circular convex colonies of 1–2 mm diameter on plates containing YED-P medium (per liter: 7.0 g of glucose, 3.0 g of yeast extract, 3.0 g of bicalcium phosphate, and 17.0 g of agar) within 2 days at 25 °C [8]. P. lutea OK2T is capable of oxidizing glucose in media containing ammonium nitrate as a nitrogen source and hydrolyzes aesculin [8]. The strain OK2T is positive for catalase, but negative for oxidase, gelatinase, caseinase, urease, β-galactosidase, arginine dehydrolase, tryptophan deaminase, and indole/H2S [8]. Further, it can utilize galactose, ribose, mannose, glycerol, D-fructose, D-xylose, D-/L-arabinose, D-/L-arabitol, D-/L-fucose, L-lyxose, melibiose, inositol, mannitol, adonitol, xylitol, caprate, malate, gluconate, 2-ketogluconate, and citrate as sole carbon sources, but cannot utilize maltose, lactose, sucrose, trehalose, cellobiose, starch, glycogen, inulin, sorbitol, D-tagatose, D-raffinose, L-xylose, L-sorbose, L-rhamnose, N-acetylglucosamine, salicin, and erythritol [8]. Unlike other pseuodomonads, the strain OK2T does not produce fluorescent pigments [8].

Fig. 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of Pseudomonas lutea OK2T. The image was taken under a Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM, SU8220; Hitachi, Japan) at an operating voltage of 5.0 kV. The scale bar represents 10.0 μm

Chemotaxonomic data

The important non-polar fatty acids present in P. lutea OK2T include hexadecenoic acid (16:1, 39.0 %), hexadecanoic acid (16:0, 29.0 %), and octadecenoic acid (18:1, 18.6 %). In addition, the strain OK2T has hydroxy fatty acids such as 3-hydroxydodecanoic acid (3-OH 12:0, 3.3 %), 2-hydroxydodecanoic acid (2-OH 12:0, 2.7 %), and 3-hydroxydecanoic acid (3-OH 10:0, 2.4 %) [8]. The whole-cell fatty acid profile of this strain is similar to that observed in other representative strains of the genus Pseudomonas, such as P. graminis [10] and P. rhizosphaerae [11]. The general characteristics of the strain are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Classification and general features of Pseudomonas lutea OK2T [18]

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [64] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [65] | ||

| Class Gammaproteobacteria | TAS [66, 67] | ||

| Order Pseudomonadales | TAS [47, 68, 69] | ||

| Family Pseudomonadaceae | TAS [47, 70] | ||

| Genus Pseudomonas | TAS [47, 71–73] | ||

| Species Pseudomonas lutea | TAS [8] | ||

| Type strain OK2T (=LMG 21974T, CECT 5822T) | TAS [8] | ||

| Gram stain | Negative | TAS [8, 74] | |

| Cell shape | Rod-shaped | TAS [8, 74] | |

| Motility | Motile | TAS [8, 74] | |

| Sporulation | None | TAS [8, 74] | |

| Temperature range | Mesophilic | NAS | |

| Optimum temperature | 25°C | TAS [8] | |

| pH range | 7.0–7.5 | NAS | |

| Carbon source | Heterotrophic | TAS [75] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Soil | TAS [8] |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | Not reported | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobic | TAS [8, 74] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationships | Free living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Non-pathogen | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Spain; northern Spain | TAS [8] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection | 2003 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | Not reported | |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | Not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Not reported |

aEvidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [76]

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

P. lutea OK2T was selected as a novel-phosphate solubilizing strain for the genome-sequencing project of agriculturally useful microbes undertaken at Kyungpook National University. Genome sequencing was performed in September 2014, and the results of the Whole Genome Shotgun project have been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession number JRMB00000000. The version described in this study is the first version, indicated as JRMB00000000.1. The information obtained from the genome sequencing project is registered on the Genome Online Database [17] with the GOLD Project ID Gp0107463. A summary of this information and its association with the Minimum Information about a Genome Sequence (MIGS) version 2.0 compliance [18] are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Project information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | 10-kb SMRT-bell library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | PacBio RS II |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 67.58 × |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | RS HGAP Assembly Protocol [20] in SMRT analysis pipeline v.2.2.0 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline [77]; GeneMarkS+ [78] |

| Locus Tag | LT42 | |

| Genbank ID | JRMB00000000 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | September 29, 2014 | |

| GOLD ID | Gp0107463 | |

| BIOPROJECT | PRJNA261881 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | LMG 21974T, CECT 5822T |

| Project relevance | Agriculture |

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

The strain was cultured in tryptic soy broth (Difco Laboratories Inc., Detroit, MI) at 30 °C on a rotary shaker at 200 rpm. Genomic DNA was isolated using a QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's standard protocol. The quantity and purity of the extracted genomic DNA were assessed using a Picodrop Microliter UV/Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) and Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Fisher Scientific Inc., Pittsburgh, PA), respectively.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The isolated genomic DNA of P. lutea OK2T was sequenced using the SMRT DNA sequencing platform and the Pacific Biosciences RS II sequencer with P4 polymerase-C2 sequencing chemistry (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA) [19]. After shearing the genomic DNA, a 10-kb insert SMRT-bell library was prepared and loaded on two SMRT cells. During the 90 min of movie time, 654,270,150 read bases were generated from 300,584 reads. All the obtained bases were filtered to remove any reads shorter than 100 bp or those having accuracy values less than 0.8. Subsequently, 461,880,761 nucleotides were obtained from 116,562 reads, with a read quality of 0.843. These bases were assembled de novo using the RS HGAP assembly protocol version 3.3 on the SMRT analysis platform version 2.2.0 [20]. The HGAP analysis yielded five contigs corresponding to five scaffolds, with a 67.58-fold coverage. The maximum contig length and N50 contig length were identical: 2,839,280 bp. The total length of the P. lutea OK2T genome was found to be 5,647,497 bp.

Genome annotation

The protein coding sequences were determined using the NCBI PGAP version 2.8 (rev. 447021) [21]. Additional gene prediction and functional annotation analyses were performed on the RAST server [22] and IMG-ER pipeline, respectively, by the Department of Energy-Joint Genome Institute [23].

Genome properties

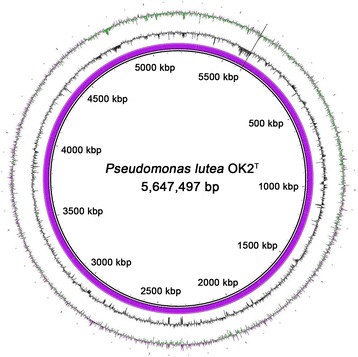

The average G + C content of the genome was 60.15 %. The genome was predicted to encode 4,941 genes including 4,846 protein-coding genes and 95 RNA genes (24 rRNAs, 70 tRNAs, and 1 ncRNA). Putative functions were assigned to 4,102 of the protein-coding genes, and 3,507 genes (approximately 70.98 %) were assigned to the COG functional categories. The most abundant COG category was "Amino acid transport and metabolism" (10.36 %), followed by "General function prediction only" (8.71 %), “Transcription" (8.34 %), and “Signal transduction mechanisms” (6.52 %). The category for “Mobilome: prophages, transposons” (0.92 %) was also classified with functional genes for transposase (LT42_00515, LT42_05870, LT42_07855, LT42_10965, LT42_14240, LT42_14330, LT42_18595, LT42_19270, LT42_21870, LT42_21925), integrase (LT42_17205), terminase (LT42_06460, LT42_17145, LT42_17150), and plasmid stabilization protein (LT42_19025, LT42_24175). The genome statistics of strain OK2T are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 3. The gene distribution within the COG functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Genome statistics

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 5,647,497 | 100.00 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 4,778,153 | 84.61 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 3,397,087 | 60.15 |

| DNA scaffolds | 5 | 100.00 |

| Total genes | 4,941 | 100.00 |

| Protein coding genes | 4,846 | 98.08 |

| RNA genes | 95 | 1.92 |

| Pseudo genes | 239 | 4.84 |

| Genes in internal clusters | 1,402 | 26.64 |

| Genes with function prediction | 4,102 | 83.02 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3,507 | 70.98 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 4,026 | 81.48 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 485 | 9.82 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,026 | 20.77 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 | 0.00 |

Fig. 3.

Graphical circular map of the Pseudomonas lutea OK2T genome. The circular map was generated using the BLAST Ring Image Generator program [79]. From the inner circle to the outer circle: Genetic regions; GC content (black); and GC skew (purple/green)

Table 4.

Number of genes associated with general COG functional categories

| Code | Value | % age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 231 | 5.75 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 1 | 0.02 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 335 | 8.34 | Transcription |

| L | 121 | 3.01 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 2 | 0.05 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 34 | 0.85 | Cell cycle control, Cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| V | 73 | 1.82 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 262 | 6.52 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 228 | 5.68 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 133 | 3.31 | Cell motility |

| U | 97 | 2.41 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 152 | 3.78 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 248 | 6.17 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 256 | 6.37 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 416 | 10.36 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 85 | 2.12 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 198 | 4.93 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 182 | 4.53 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 234 | 5.83 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 98 | 2.44 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 350 | 8.71 | General function prediction only |

| S | 212 | 5.28 | Function unknown |

| - | 1434 | 29.02 | Not in COGs |

The total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the genome

Insights from the genome sequence

Microorganisms that show phosphate-solubilizing activity are generally known to be involved in either of the following two biochemical mechanisms: production of organic acids for the acidification of external surroundings for plants and production of enzymes for direct solubilization [24, 25]. Genes encoding functional enzymes with these biochemical properties were predicted using the KO database via IMG-ER pipeline [26, 27]. The genome of P. lutea OK2T was annotated with several genes involved in phosphate solubilization. For example, ldhA (D-lactate dehydrogenase, KO:K03778) and icd (isocitrate dehydrogenase, KO:K00031) were found to be involved in the production of organic acids, and phoD (alkaline phosphatase D, KO:K01113) was involved in direct phosphate solubilization. Direct oxidation of glucose to gluconic acid by a periplasmic membrane-bound glucose dehydrogenase is also known to be one of the major metabolic steps for phosphate solubilization in pseudomonads [6]. In relation to this process, the gcd gene coding for a cofactor pyrroloquinoline quinone-dependent glucose dehydrogenase (=quinoprotein glucose dehydrogenase, KO:K00117) was revealed (Table 5). Phosphate solubilization is normally a complex phenomenon depending on conditions such as bacterial, nutritional, physiological, and growth variations [2]. Given that phosphate solubilization can occur through various microbial processes/mechanisms [28], the predicted genes on the genome being described could compositely contribute to this activity.

Table 5.

Putative genes related to functional enzymes for potential PGPR effects predicted from the genome sequence of Pseudomonas lutea OK2T

| Function ID | Name |

|---|---|

| Phosphate solubilization | |

| KO:K01113 | alkaline phosphatase D [EC:3.1.3.1] (phoD) |

| KO:K03778* | D-lactate dehydrogenase [EC:1.1.1.28] (ldhA) * |

| KO:K00031 | isocitrate dehydrogenase [EC:1.1.1.42] (icd) |

| KO:K01647 | citrate synthase [EC:2.3.3.1] (gltA) |

| KO:K00117 | quinoprotein glucose dehydrogenase [EC:1.1.5.2] (gcd) |

| Antibiotic resistance | |

| KO:K17836* | beta-lactamase class A (penicillinase) [EC:3.5.2.6] (penP) * |

| KO:K08218 | MFS transporter, PAT family, beta-lactamase induction signal transducer AmpG (ampG) |

| KO:K03806 | beta-lactamase expression regulator, N-acetyl-anhydromuramyl-L-alanine amidase AmpD protein (ampD) |

| KO:K03807 | Membrane protein required for beta-lactamase induction, AmpE protein (ampE) |

| KO:K05365 | penicillin-binding protein 1B [EC:2.4.1.129 3.4.-.-] (mrcB) |

| KO:K05366 | penicillin-binding protein 1A [EC:2.4.1.-3.4.-.-] (mrcA) |

| KO:K05367 | penicillin-binding protein 1C [EC:2.4.1.-] (pbpC) |

| KO:K05515 | penicillin-binding protein 2 (mrdA) |

| KO:K07552 | MFS transporter, DHA1 family, bicyclomycin/chloramphenicol resistance protein (bcr) |

| KO:K08223 | MFS transporter, FSR family, fosmidomycin resistance protein (fsr) |

| KO:K05595* | multiple antibiotic resistance protein (marC) * |

| KO:K18138 | multidrug efflux pump (acrB, mexB, adeJ, smeE, mtrD, cmeB) |

| KO:K07799 | putative multidrug efflux transporter MdtA (mdtA) |

| KO:K07788 | RND superfamily, multidrug transport protein MdtB (mdtB) |

| KO:K07789 | RND superfamily, multidrug transport protein MdtC (mdtC) |

| Toxins | |

| KO:K11068 | membrane damaging toxins Type II toxin, pore-forming toxin hemolysin III (hlyIII) |

| Metal ion resistance | |

| KO:K07213 | copper chaperone |

| KO:K07245 | putative copper resistance protein D (pcoD) |

| KO:K07665 | two-component system, OmpR family, copper resistance phosphate regulon response regulator CusR (cusR) |

| KO:K06189 | magnesium and cobalt transporter (corC) |

| KO:K08970* | nickel/cobalt exporter (rcnA) * |

| KO:K06213 | magnesium transporter (mgtE) |

| KO:K16074 | zinc transporter (zntB) |

| KO:K09815 | zinc transport system substrate-binding protein (znuA) |

| KO:K09816 | zinc transport system permease protein (znuB) |

| KO:K09823 | Fur family transcriptional regulator, zinc uptake regulator (zur) |

| KO:K03893 | arsenical pump membrane protein (arsB) |

| KO:K11811* | arsenical resistance protein ArsH (arsH) * |

| Siderophore | |

| KO:K02362 | enterobactin synthetase component D [EC:2.7.8.-] (entD) |

| KO:K16090 | catecholate siderophore receptor (fiu) |

| Attachment and colonization in the plant rhizosphere | |

| KO:K04095* | cell filamentation protein (fic) * |

| KO:K06596* | chemosensory pili system protein ChpA (sensor histidine kinase/response regulator) (chpA) * |

| KO:K02655, K02656, K02662, K02663, K02664, K02665, K02666, K02671, K02672, K02673, K02674, K02676, K02650*, K02652, K02653 | type IV pilus assembly protein PilE (pilE), PilF (pilF), PilM (pilM), PilN (pilN), PilO (pilO), PilP (pilP), PilQ (pilQ), PilV (pilV), PilW (pilW), PilX (pilX), PilY1 (pilY1), PilZ (pilZ), PilA (pilA)*, PilB (pilB), PilC (pilC) |

| KO:K08086, K02280 | pilus assembly protein FimV (fimV), CpaC (cpaC) |

| KO:K02657, K02658 | twitching motility two-component system response regulator PilG (pilG), PilH (pilH) |

| KO:K02659, K02660, K02669, K02670* | twitching motility protein PilI (pilI), PilJ (pilJ), PilT (pilT), PilU (pilU) * |

| Secretion system | |

| KO:K03196*, K03198*, K03199*, K03200*, K03203*, K03204*, K03205* | type IV secretion system protein VirB11 (virB11) *, VirB3 (virB3) *, VirB4 (virB4) *, VirB5 (virB5) *, VirB8 (virB8) *, VirB9 (virB9) *, VirD4 (virD4) * |

| KO:K11891*, K11892*, K11893*, K11894*, K11895*, K11896*, K11900*, K11901* | type VI secretion system protein ImpL (impL) *, ImpK (impK) *, ImpJ (impJ) *, ImpI (impI) *, ImpH (impH) *, ImpG (impG) *, ImpC (impC) *, ImpB (impB) * |

| KO:K11903*, K11904* | type VI secretion system secreted protein Hcp (hcp) *, VgrG (vgrG) * |

| KO:K11905* | type VI secretion system protein* |

| KO:K11906*, K11907*, K11910* | type VI secretion system protein VasD (vasD) *, VasG (vasG) *, VasJ (vasJ) * |

| Plant hormone auxin biosynthesis | |

| KO:K01696 | tryptophan synthase [EC:4.2.1.20] (trpB) |

| KO:K00766 | anthranilate phosphoribosyltransferase [EC:2.4.2.18] (trpD) |

| KO:K01817 | phosphoribosylanthranilate isomerase [EC:5.3.1.24] (trpF) |

aBased on the function profiles obtained from the KO database [25, 26], under the IMG-ER pipeline [23]

*Predicted only in the genome sequence of P. lutea OK2T (IMG Genome ID 2593339262) upon comparison with the complete genome sequence of P. rhizosphaerae IH5T (=DSM 16299T, IMG Genome ID 2593339263) [34]

P. lutea OK2T is also expected to possess functional traits related to plant growth promotion [29–32]. As shown in Table 5, genes coding for functional enzymes with various PGPR effects such as “antibiotic resistance”, “metal ion resistance”, “toxin production”, “siderophore production”, “attachment and colonization in the plant rhizosphere”, and “plant hormone auxin production” were revealed. Although nif gene clusters involved in nitrogen-fixing activity were not found in the strain OK2T, a gene encoding for the nitrogen-fixation protein NifU (KO:K04488) was identified [33].

Within the genus Pseudomonassensu stricto, P. lutea OK2T is presented as a group phylogenetically closest to P. graminisDSM 11363T [10] and P. rhizosphaerae IH5T [11] (shown in Fig. 1). The majority of the genes in P. lutea OK2T were predicted based on the genome of P. rhizosphaerae IH5T (=DSM 16299T, IMG Genome ID 2593339263) [34]. However, genes such as ldhA (D-lactate dehydrogenase, KO:K03778), penP (beta-lactamase class A, KO:K17836), marC (multiple antibiotic resistance protein, KO:K05595), rcnA (nickel/cobalt exporter, KO:K08970), arsH (arsenical resistance protein ArsH, KO:K11811), fic (cell filamentation protein, KO:K04095), and chpA (chemosensory pili system protein ChpA, KO:K06596) and the gene clusters coding for enzymes with type IV secretion systems were only annotated in OK2T. Furthermore, pertinent gene clusters for type VI secretion systems, known as a complex multicomponent secretion machine, with bacterial competitions [35–37] were only predicted in the strain OK2T. The type VI secretion system may be related to possible features of bacterial motility/adaptation/competition in the strain. Although the strain P. graminisDSM 11363T had similar general features and biochemical properties as strain OK2T, its genome sequence is not yet available.

Average Nucleotide Identity calculations [38] were used to compare the genomes of P. lutea OK2T and other sequenced Pseudomonas species (Table 6). The strain was found to be most closely related to Pseudomonas syringaeATCC 19310T (77.31 % identity), followed by Pseudomonas kilonensis 520-20T (76.96 % identity). These values are under the acceptable range of species cutoff values of 95–96 % [39], indicating that P. lutea OK2T is different from other sequenced Pseudomonas species.

Table 6.

Average nucleotide identity of the genome sequence of different Pseudomonas species with that of OK2T

| Strain | Average Nucleotide Identity (%) |

|---|---|

| Pseudomonas syringae ATCC 19310T | 77.31 |

| Pseudomonas kilonensis 520-20T | 76.96 |

| Pseudomonas protegens CHA0T | 76.86 |

| Pseudomonas veronii CIP 104663T | 76.72 |

| Pseudomonas libanensis CIP 105460T | 76.48 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens CCM 2115T | 76.45 |

| Pseudomonas synxantha IAM 12356T | 76.39 |

| Pseudomonas rhizosphaerae IH5T | 76.39 |

| Pseudomonas putida IAM 1236T | 75.59 |

| Pseudomonas monteilii CIP 104883T | 75.39 |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri ATCC 17588T | 73.85 |

Conclusions

We presented here the first genome sequence of P. lutea OK2T, a phosphate-solubilizing bacterium isolated from the rhizosphere of grass in northern Spain [8]. This study showed that P. lutea OK2T has potential traits including phosphate-solubilizing capability, making it as an effective pseudomonad-PGPR.

Considering a variety of complex conditions that occur in rhizospheres [40], the environmental adaptability of PGPR in in situ rhizosphere became an important factor for improved plant growth-promoting capacity. In addition, initial studies focusing on the functional properties of PGPR [31, 32] have led to interest in the comparative analyses of pan-/core-genomes of these bacteria, which are of ecological importance for elucidating the fundamental genotypic features of PGPR under diverse rhizosphere conditions [41, 42]. The genetic information obtained for P. lutea OK2T will improve our understanding of the genetic basis of phosphate-solubilizing pseudomonad-PGPR activities and further provide insights into the practical applications of the strain as a biocontrol agent in the field of agriculture.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2015R1D1A1A01057187).

Authors’ contributions

YK performed the genomic sequencing, genomic analyses, phenotypic characterization of the bacterium, and drafted the manuscript. GP performed the genomic analyses and drafted the manuscript. JHS conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and drafted the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- HGAP

Hierarchical genome assembly process

- IMG-ER

Integrated microbial genomes-expert review

- KO

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes Orthology

- PGAP

Prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline

- PGPR

Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria

- RAST

Rapid annotation using subsystems technology

- SMRT

Single molecule real-time

References

- 1.Ehrlich HL. Mikrobiologische and biochemische Verfahrenstechnik. 2. VCH: Verlagsgesellschaft, Weinheim; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vyas P, Gulati A. Organic acid production in vitro and plant growth promotion in maize under controlled environment by phosphate-solubilizing fluorescent Pseudomonas. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9(1):174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan MS, Zaidi A, Ahmad E. Mechanism of phosphate solubilization and physiological functions of phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms. In: Khan MS, Zaidi A, Musarrat J, editors. Phosphate solubilizing microorganisms. Springer-International Publishing; 2014: p. 31–62. http://www.springer.com/kr/book/9783319082158.

- 4.Rodríguez H, Fraga R. Phosphate solubilizing bacteria and their role in plant growth promotion. Biotech Adv. 1999;17(4–5):319–339. doi: 10.1016/S0734-9750(99)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haas D, Defago G. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(4):307–319. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer JB, Frapolli M, Keel C, Maurhofer M. Pyrroloquinoline quinone biosynthesis gene pqqC, a novel molecular marker for studying the phylogeny and diversity of phosphate-solubilizing pseudomonads. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(20):7345–7354. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05434-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vacheron J, Desbrosses G, Bouffaud ML, Touraine B, Moenne-Loccoz Y, Muller D, et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and root system functioning. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:356. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peix A, Rivas R, Santa-Regina I, Mateos PF, Martínez-Molina E, Rodríguez-Barrueco C, et al. Pseudomonas lutea sp. nov., a novel phosphate-solubilizing bacterium isolated from the rhizosphere of grasses. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54(3):847–850. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02966-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behrendt U, Ulrich A, Schumann P, Erler W, Burghardt J, Seyfarth W. A taxonomic study of bacteria isolated from grasses: a proposed new species Pseudomonas graminis sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49(1):297–308. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-1-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peix A, Rivas R, Mateos PF, Martínez-Molina E, Rodríguez-Barrueco C, Velázquez E. Pseudomonas rhizosphaerae sp. nov., a novel species that actively solubilizes phosphate in vitro. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53(6):2067–2072. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02703-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramette A, Moenne-Loccoz Y, Defago G. Polymorphism of the polyketide synthase gene phID in biocontrol fluorescent pseudomonads producing 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol and comparison of PhID with plant polyketide synthases. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2001;14(5):639–652. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.5.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramette A, Frapolli M, Saux MF-L, Gruffaz C, Meyer J-M, Défago G, et al. Pseudomonas protegens sp. nov., widespread plant-protecting bacteria producing the biocontrol compounds 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol and pyoluteorin. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2011;34(3):180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coroler L, Elomari M, Hoste B, Gillis M, Izard D, Leclerc H. Pseudomonas rhodesiae sp. nov., a new species isolated from natural mineral waters. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19(4):600–607. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(96)80032-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peix A, Berge O, Rivas R, Abril A, Velázquez E. Pseudomonas argentinensis sp. nov., a novel yellow pigment-producing bacterial species, isolated from rhizospheric soil in Córdoba, Argentina. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55(3):1107–1112. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63445-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4(4):406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddy TB, Thomas AD, Stamatis D, Bertsch J, Isbandi M, Jansson J, et al. The Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) v. 5: a metadata management system based on a four level (meta)genome project classification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D1099–106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotech. 2008;26(5):541–547. doi: 10.1038/nbt1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eid J, Fehr A, Gray J, Luong K, Lyle J, Otto G, et al. Real-time DNA sequencing from single polymerase molecules. Science. 2009;323(5910):133–138. doi: 10.1126/science.1162986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chin C-S, Alexander DH, Marks P, Klammer AA, Drake J, Heiner C, et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat Meth. 2013;10(6):563–569. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tatusova T, DiCuccio M, Badretdin A, Chetvernin V, Ciufo S, Li W. The NCBI Handbook. 2. Bethesda: National Center for Biotechnology Information; 2013. Prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, et al. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen I-MA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(17):2271–2278. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghosh P, Rathinasabapathi B, Ma LQ. Phosphorus solubilization and plant growth enhancement by arsenic-resistant bacteria. Chemosphere. 2015;134:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vassileva M, Serrano M, Bravo V, Jurado E, Nikolaeva I, Martos V, et al. Multifunctional properties of phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms grown on agro-industrial wastes in fermentation and soil conditions. Appl Microbial Biotechnol. 2010;85:1287–1299. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D199–205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behera BC, Singdevsachan SK, Mishra RR, Dutta SK, Thatoi HN. Diversity, mechanism and biotechnology of phosphate solubilizing microorganism in mangrove – A review. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2014;3:97–110. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta DK, Chatterjee S, Datta S, Veer V, Walther C. Role of phosphate fertilizers in heavy metal uptake and detoxification of toxic metals. Chemosphere. 2014;108:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pereira SIA, Castro PML. Phosphate-solubilizing rhizobacteria enhance Zea mays growth in agricultural P-deficient soils. Ecol Eng. 2014;73:526–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.09.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vassilev N, Vassileva M, Nikolaeva I. Simultaneous P-solubilizing and biocontrol activity of microorganisms: potentials and future trends. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;71(2):137–144. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0380-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhattacharyya PN, Jha DK. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): emergence in agriculture. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;28(4):1327–1350. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0979-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang DM, Dempsey A, Tan KT, Liew CC. A modular domain of NifU, a nitrogen fixation cluster protein, is highly conserved in evolution. J Mol Evol. 1996;43(5):536–540. doi: 10.1007/BF02337525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwak Y, Jung BK, Shin JH. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas rhizosphaerae IH5T (=DSM 16299T), a phosphate-solubilizing rhizobacterium for bacterial biofertilizer. J Biotechnol. 2015;193:137–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Filloux A, Hachani A, Bleves S. The bacterial type VI secretion machine: yet another player for protein transport across membranes. Microbiology. 2008;154(Pt 6):1570–1583. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/016840-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Decoin V, Barbey C, Bergeau D, Latour X, Feuilloley MG, Orange N, et al. A type VI secretion system is involved in Pseudomonas fluorescens bacterial competition. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Decoin V, Gallique M, Barbey C, Mauff FL, Poc CD, Feuilloley MGJ, et al. A Pseudomonas fluorescens type 6 secretion system is related to mucoidy, motility and bacterial competition. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:72–84. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0405-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goris J, Konstantinidis KT, Klappenbach JA, Coenye T, Vandamme P, Tiedje JM. DNA–DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57(1):81–91. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(45):19126–19131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906412106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berg G, Smalla K. Plant species and soil type cooperatively shape the structure and function of microbial communities in the rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2009;68(1):1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen X, Hu H, Peng H, Wang W, Zhang X. Comparative genomic analysis of four representative plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria in Pseudomonas. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:271. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roca A, Pizarro-Tobias P, Udaondo Z, Fernandez M, Matilla MA, Molina-Henares MA, et al. Analysis of the plant growth-promoting properties encoded by the genome of the rhizobacterium Pseudomonas putida BIRD-1. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15(3):780–794. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benson DA, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Sayers EW. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D32–37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(21):2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.List Editor. Validation of the publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSB. List No. 61. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:601–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved lists of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1980;30(1):225–420. doi: 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stevens FL. Plant disease fungi. New York: The MacMillan Co; 1925. p. 469. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elomari M, Coroler L, Hoste B, Gillis M, Izard D, Leclerc H. DNA relatedness among Pseudomonas strains isolated from natural mineral waters and proposal of Pseudomonas veronii sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46(4):1138–1144. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paine SG. Studies in bacteriosis II: a brown blotch disease of cultivated mushrooms. Ann Appl Biol. 1919;5:206–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1919.tb05291.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Migula W. Bacteriaceae (Stabchenbacterien) In: Engler A, Prantl K, editors. Die Natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann; 1895. pp. 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dabboussi F, Hamze M, Elomari M, Verhille S, Baida N, Izard D, et al. Pseudomonas libanensis sp. nov., a new species isolated from Lebanese spring waters. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49(Pt 3):1091–1101. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-3-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holland DF. V. Generic index of the commoner forms of bacteria. In: Winslow CEA, Broadhurst J, Buchanan RE, Krumwiede C Jr, Rogers LA, Smith GH, editors. The families and genera of the bacteria. 1920. pp. 191–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sikorski J, Stackebrandt E, Wackernagel W. Pseudomonas kilonensis sp. nov., a bacterium isolated from agricultural soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51:1549–1555. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-4-1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.List Editor. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. List No. 146. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2012;62:1443–5.

- 56.List Editor. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. List No. 145. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2012;62:1017–9.

- 57.Lang E, Burghartz M, Spring S, Swiderski J, Sproer C. Pseudomonas benzenivorans sp. nov. and Pseudomonas saponiphila sp. nov., represented by xenobiotics degrading type strains. Curr Microbiol. 2010;60(2):85–91. doi: 10.1007/s00284-009-9507-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Hall CJJ. Bijdragen tot de kennis der Bakterieele Plantenziekten. Inaugural Dissertation Amsterdam. 1902. p. 198.

- 59.List Editor. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. List No. 154. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 2013;63:3931–4.

- 60.Migula W. Schizomycetes (Bacteria, Bacterien) In: Engler A, Prantl K, editors. Die Natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann; 1895. pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Elomari M, Coroler L, Verhille S, Izard D, Leclerc H. Pseudomonas monteilii sp. nov., isolated from clinical specimens. Int Journal Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47(3):846–852. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-3-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sijderius R. Heterotrophe bacterien, die thiosulfaat oxydeeren. 1946. Heterotrophe bacterien, die thiosulfaat oxydeeren; pp. 1–146. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hildebrand DC, Palleroni NJ, Hendson M, Toth J, Johnson JL. Pseudomonas flavescens sp. nov., isolated from walnut blight cankers. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44(3):410–415. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-3-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(12):4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria phyl. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Kreig NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. New York: Springer; 2005. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 66.List Editor. Validation of publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSEM. List no. 106. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55(6):2235–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Class III. Gammaproteobacteria class. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Kreig NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. New York: Springer; 2005. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Orla-Jensen S. The main lines of the natural bacterial system. J Bacteriol. 1921;6(3):263–273. doi: 10.1128/jb.6.3.263-273.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Order IX. Pseudomonales. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Kreig NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. New York: Springer; 2005. p. 323. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Winslow CE, Broadhurst J, Buchanan RE, Krumwiede C, Rogers LA, Smith GH. The families and genera of the bacteria: preliminary report of the committee of the society of american bacteriologists on characterization and classification of bacterial types. J Bacteriol. 1917;2(5):505–566. doi: 10.1128/jb.2.5.505-566.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Migula W. Über ein neues System der Bakterien. Arb Bakt Inst Karlsruhe. 1894;1:235–238. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Doudoroff M, Palleroni NJ. Genus I. Pseudomonas Migula 1894, 237 Nom. cons. Opin. 5, Jud. Comm. 1952, 121. In: Buchanan RE, Gibbons NE, editors. Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology. Baltimore: The Williams and Wilkins Co; 1974. pp. 217–243. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Judicial Commission Opinion 5 Conservation of the generic name Pseudomonas Migula 1894 and designation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Schroeter) Migula 1900 as type species. Int Bull Bacteriol Nomencl Taxon. 1952;2:121–122. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Palleroni NJ. Genus I. Pseudomonas. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Kreig NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 323–357. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Palleroni NJ. Genus I. Pseudomonas. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Kreig NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 373–377. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kodaka H, Armfield AY, Lombard GL, Dowell VR., Jr Practical procedure for demonstrating bacterial flagella. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16(5):948–952. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.5.948-952.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Angiuoli SV, Gussman A, Klimke W, Cochrane G, Field D, Garrity G, et al. Toward an online repository of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for (meta)genomic annotation. Omics. 2008;12(2):137–141. doi: 10.1089/omi.2008.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lukashin AV, Borodovsky M. GeneMark.hmm: new solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(4):1107–1115. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alikhan N-F, Petty N, Ben Zakour N, Beatson S. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genomics. 2011;12(1):402. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]